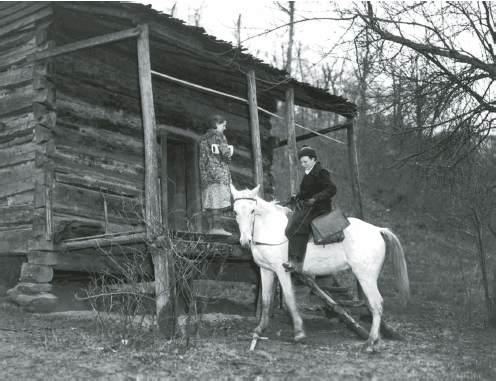

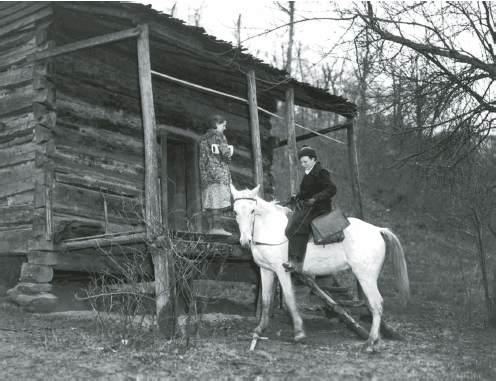

A Pack Horse librarian visiting a reader. (WPA)

CHAPTER FOUR

The Great Depression and the New Deal

During the 1920s there were real increases in prosperity in Kentucky, especially in cities.1 These conditions ended with the Great Depression. The conventional beginning of the Depression is the stock market crash of 1929, although there were hard times in rural Kentucky earlier than this, related to the collapse of farm commodity prices after World War I. The Depression touched many Kentuckians early and deeply and had a lasting impact on life in the commonwealth. It created an economic vacuum of joblessness, insolvent banks, and low prices for agricultural commodities. To deal with the Depression, there was massive government spending through various New Deal programs. In this chapter I discuss some of the government programs that changed Kentucky foodways and often led to new cookbooks. Although the Depression era saw fewer cookbooks published, there were some interesting recipe compilations supported by the Work Projects Administration (WPA) through its Pack Horse Libraries, housekeeping aides training programs, and the America Eats program of the Federal Writers’ Project.2 All these national projects had a presence in Kentucky.

The WPA, announced in 1935 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt during one of his Fireside Chat radio broadcasts, was funded by Congress to help overcome the country’s impoverishment. It was the largest of the New Deal programs and continued to operate until 1943. The WPA was a “work relief program” whose budget was intended to provide “wages for labor” in localities with high numbers of people on the “relief rolls,” rather than to pay for materials and administrative staff (Roosevelt 2012). The core of the program was the construction of roads, sewers, and public buildings in both urban and rural settings, but other activities were funded as well. For example, the WPA was involved in distributing food to the poor, although the primary goal was to enhance farm families’ incomes rather than to provide a sound diet to impoverished individuals. The government purchased surpluses—called “surplus relief commodities”—that farmers were unable to sell in the market. The kinds of foods purchased and distributed varied, depending on what was available, but they included flour, dried beans and peas, prunes, oat cereal, onions, butter, corned beef, canned goods such as beans and tomatoes, sugar, apples, and cheese. These foods were distributed twice a month at grocery stores on what came to be called “giveaway days.” One government report, describing these events in a rural setting, states, “The relief clients in many cases start gathering at the commodity centers before the merchant has opened his store for the day’s business. Some come by wagon, some mule back, but most of them have only their feet for conveyance” (Works Progress Administration 1935). This program introduced some new foods, such as skim milk powder, to people who were eligible for relief.

The WPA program resulted in the writing of a few cookbooks and other materials related to foodways. The first considered here are the recipe books compiled by staff members of the Pack Horse Library project, which was active in thirty eastern Kentucky counties (Appelt and Schmitzer 2001). Whereas most other WPA programs focused on hiring men, the Pack Horse Library project was staffed by women, and the individuals hired had to be otherwise unemployable. They came to be called the “Book Women.” From the county seats, where the Pack Horse Library programs were established, the Book Women traveled by horse or mule and delivered library materials to readers without access to public libraries. Their routes, which they rode every two weeks, averaged eighteen miles. Because these programs had no budgets to actually buy books, they had to rely on reading materials created by the Book Women themselves and on discards from other libraries and schools. There was considerable demand for these materials, especially for content focused on homemaking. Borrowers often requested recipes, so cookbooks were very popular, and short compilations of recipes were produced by the Pack Horse Libraries in some counties. I found two of these: one was in a file of WPA materials at the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives in Frankfort, which was from the program in McKee, in Jackson County; the other, which I found in the online catalog of the Louisville Free Public Library, was from Whitley County (Whitley Pack Horse Library 1938). Both are quite brief, containing just over thirty recipes.

A Pack Horse librarian visiting a reader. (WPA)

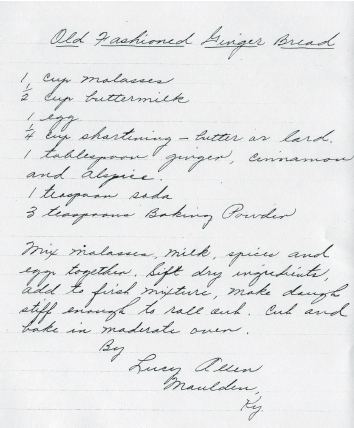

The volume from McKee is handwritten, and the recipe format is standard. Some of the recipes are attributed to specific women, who were probably program participants. The inside front page states: “This book contains ‘Auld Tyme’ Cooking and Canning recipes.” The manuscript concludes with “household hints.” More than half the recipes are for sweets, including pies, cakes, and candy. In addition, there are recipes for biscuits, cornbread, and various vegetable preparations. Although this volume is undated, I assume it is from the late 1930s. The recipe for gingerbread, an important mountain preparation, is shared here.

Old-fashioned Ginger Bread (1930s)

1 cup molasses

½ cup buttermilk

1 egg

¼ cup shortening—butter or lard

1 tablespoon ginger, cinnamon and allspice

1 teaspoon soda

3 teaspoons baking powder

Mix molasses, milk, spices and egg together. Sift dry ingredients, add to first mixture, make dough stiff enough to roll out. Cut and bake in moderate oven. (WPA [1930s?])

A recipe from a Jackson, Kentucky, Pack Horse Library cookbook.

This recipe was contributed by Lucy Allen of Maulden, in Jackson County. Note that the term molasses was widely used to refer to sorghum syrup.

Another interesting dessert recipe is the following unsigned one for cold biscuit pudding. It is notable that the condition of the milk is specified—in this case, the recipe calls for sweet milk. This was common practice in an era when refrigeration was limited and milk often soured. In fact, many recipes call for sour milk.

Cold Biscuit Pudding (1930s)

some cold biscuits

½ cup hot water

1½ cups sweet milk

3 egg yolks

1 cup sugar

egg whites

Crumble up cold biscuits and pour ½ cup boiling water over them. Cover and let stand 5 minutes. Add 1½ cups sweet milk, 3 egg yolks and 1 cup sugar. Stir into biscuits and water. Place in oven and let stand until milk and egg yolks are cooked. Flavor if desired. Beat egg whites stiffly and sweeten, spread over pudding and bake brown. (WPA [1930s?])

The other collection of recipes, a typescript entitled Mountain Receipts, was compiled by the Whitley Pack Horse Library and published in 1938. It has a more clearly expressed focus than the McKee volume, as its thirty-one recipes were collected from persons 75 to 100 years old living in “isolated hill sections of Whitley County.” As the brief preface states, “We have collected, first hand, from these old people a number of recipes which were most commonly used” (Whitley Pack Horse Library 1938, 3). Almost half the recipes are made with cornmeal. Some of the dishes include hoecake, cracklin’ bread, gritted bread, cornmeal gingerbread, cornmeal pie crust, hogshead cheese, poke salad, kraut, corn muffins, berry cobbler, dried fruit stack cake, and sassafras tea. The unsigned recipes are in the block format; use mostly imprecise measures, including pinches and handfuls; do not specify times and temperatures; and contain no branded products.

Corn Meal Dumplin’s (1938)

Boil a kettle of greens with a large piece of jowl. When greens and meat are done take them out of the kettle and drop the dumplin’s in the broth that is left. To make the dumplin’ dough salt the meal you are going to use and then pour enough boiling water over the meal to make it up. Squeeze out the dumplin’s while the dough is hot. (Whitley Pack Horse Library 1938, 5)

The second recipe included here is for hogshead cheese, a variation on souse.

Hogshead Cheese (1938)

Boil Hog’s head, liver, tongue, and heart together until tender. Take the meat from bones and cut up fine. Put the cut-up meat all back in the stock where it was cooked and let come to a boil. Stir in enough corn meal to thicken, add black pepper and sage to taste and then pour this mixture out on a pan to cool. It can be sliced for sandwiches or fried in hot fat. (Whitley Pack Horse Library 1938, 7)

In addition to its culinary aspirations, the WPA trained housekeeping aides in most states to provide housekeeping services on a temporary, emergency basis to the sick or elderly. Their duties included cooking, and half of the training manual used in Kentucky consists of recipes or general advice on food preparation.3 Like the Pack Horse librarians, the aides had to be unemployed and certified as eligible for relief. The recipes in the training manual/cookbook are presented in the standard format, with the ingredients and procedures separate, and oven temperatures are specified. The recipes have a distinct “home economics professional” feel to them. For example, every recipe starts with the same instruction: “Check all materials needed. Use careful level measurements.” In some cases, lower-cost options are presented, such as how to reduce the number of eggs in a custard recipe. Some of the recipes are “beyond basic,” such as the one for peanut butter and jelly sandwiches. Here is the training manual’s recipe for summer squash.

Summer Squash and Onions (ca. 1941)

2 quarts summer squash, diced

4 tablespoons butter*

¼ cup minced onion

2 teaspoons salt

¼ teaspoon pepper

1 cup hot water

Method

1. Check all materials needed. Use careful level measurements.

2. Wash squash and dice.

3. Melt butter in a saucepan, add onion and cook until light brown.

4. Add squash, salt, pepper and 1 cup of hot water.

5. Cover saucepan [and] cook over a low flame without stirring for 10 minutes.

6. Continue cooking for 30 minutes stirring frequently during this period to keep squash from burning.

*Bacon drippings may be substituted for butter. (Works Progress Administration. 194?. Workbook for Housekeeping Aide Project, Vegetables, 17)

Kentucky and the America Eats Project

The WPA created the Federal Writers’ Project to employ out-of-work writers and other professionals. The project is best known for the many state and city travel guides it produced. Another endeavor was the creation of similar guides to America’s regional foodways, titled America Eats. The project started in 1939 by dividing the country into five geographic regions. The focus was on “American cookery and the part it has played in the national life, as exemplified in the group meals that preserve not only traditional dishes, but also attitudes and customs.” Staff writers submitted materials to project headquarters in Washington, D.C., and these materials were assigned to rewriters. Because the purpose of WPA projects was to provide a basic salary to as many Americans as possible, there were few staff writers at the top. As a result, although a lot of material was collected, few reports were published. There is no single archive collection of these documents; those that survive are located in the Library of Congress and in some state archives, and others have been lost.

Materials produced for the America Eats project have been used in some recently published volumes. Nelson Algren’s America Eats (1992) is based on materials collected in the Midwest. Algren had been hired by the Illinois branch of the Federal Writers’ Project to work on the America Eats project. John T. Edge’s A Gracious Plenty: Recipes and Recollections from the American South (1999) was influenced by the project’s concept and includes some excerpts from the materials collected, along with contemporary recipes selected from community cookbooks. The nationally focused America Eats! On the Road with the WPA by Pat Willard (2009) and The Food of a Younger Land by Mark Kurlansky (2009) are anthologies of project materials, accompanied by the authors’ contemporary materials. Willard shares his travels and observations as he revisits the basic WPA strategy of focusing on group events involving food, such as community festivals. He includes one short discussion of burgoo and its history, based on a story originally published in the Louisville Courier-Journal in 1932 (the America Eats project also collected newspaper articles and the like). The piece includes familiar stories about the dish’s origins in the Civil War and the naming of the 1932 Kentucky Derby winner Burgoo King by the owner of Idlehour Farm in Lexington. The discussion of burgoo is coupled with descriptions of Brunswick stew from North Carolina and the Minnesota-derived Booya, cooked by folks of German ethnicity. Burgoo, Brunswick stew, and Booya share some commonalities, including long cooking times, the use of assorted meats and many vegetables, and a tradition of large batches cooked mostly by men.

The Food of a Younger Land consists of selected America Eats materials, coupled with introductory essays by Kurlansky. The book’s organization is based on the project’s original geographic structure. It begins with a long but readable essay on the project itself and is illustrated with the author’s linocut prints. Kurlansky includes considerably more Kentucky material than Willard’s single burgoo recipe. He provides the menu for Christmas dinner at the Brown Hotel in 1940 and recipes for Kentucky ham bone soup, Kentucky burgoo, Kentucky oysters (aka lamb fries), Kentucky wilted lettuce, spoon bread, divinity chocolates, eggnog, the old- fashioned cocktail, and mint juleps. None of these is signed.

I found some America Eats materials at the Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, including a copy of a letter dated October 21, 1941, from Marion W. Flexner to the folks working on the project (specifically, to a Mr. Arnold). Her letter contains recipes for ham bone soup, hoppin’ John, black-eye peas, and cracklin’ cornbread (see below). The ham bone soup recipe is reprinted verbatim in the Kurlansky volume, although it is unsigned. It also appears, signed, in the Cabbage Patch Circle’s Famous Kentucky Recipes (1952). Flexner’s letter says this about cornbread: “The old time Southerner made this with the cracklings or crisp pieces of browned skin, left from rendering the lard after a ‘hog killing.’ However today in a modern kitchen we can achieve almost the same result by making our cracklings out of ground salt pork, fried crisp. Here is a very satisfactory substitute recipe for the original one.”

Cracklin’ Corn Bread (1941)

1 cup corn meal, water ground if possible

½ teaspoon soda

1 tablespoon melted fat from salt pork

4 ounces salt pork or enough to make ¼ cup of cracklings

½ cup boiling water

½ cup rich buttermilk

Salt to taste

Wash pork and dry. Put through the fine knife of the meat grinder. Fry until golden brown, then drain until crisp on brown paper. Sift the meal. Add the boiling water, then the buttermilk previously mixed with soda. Fold in the crisp cracklings. Heat an 8 inch iron skillet in a hot oven set at 400 degrees. Place 1 tablespoon of the fat from the pork in the pan and grease well. Add more salt to the batter if necessary, but usually the pork will be salty enough to season the batter. Pour the batter into the hot greased skillet and spread the fat over the surface (it will rise to the top). Return the pan to the oven and cook ½ hour or until crust is brown and bread leaves the sides of the pan. Cut into pie shaped wedges and butter while hot. (Letter from M. W. Flexner to Mr. Arnold. October 21, 1941. [KDLA])

The Louisville Courier-Journal and Kentucky Foodways

Given the hard times of the Depression, the private sector attempted to improve people’s living conditions. Accompanying this effort was a journalistic concern about economical and nutritional food preparation. It was during this era that the Louisville Courier-Journal hired its first food editor, dietitian Gladys Marie Wigginton, who wrote under the name Marie Gibson (Finley 1985, 5). In his introduction to The Courier- Journal Kentucky Cookbook, John Finley notes, “Food editors were needed to sort through the torrent of information newspapers were receiving about new food and kitchen products and to make sense out of it all for the readers” (ibid.). Gibson’s byline first appeared in 1936 and continued until 1941. Her columns often included recipes requested by readers, as well as recipes submitted in response to a weekly contest focusing on specific dishes. Aided by her neighbors, Gibson tested the recipes and selected the winners, which were printed in the paper. Her columns were frequently based on the theme of “economizing,” such as how to use “second-day” food, or leftovers. One column in the late 1930s was headed: “Suggestions for shortcuts in meat costs, heavy item in budget.” The columns also included photographs of the featured dish. Gibson introduced her recipe for “real southern apple dumplings” (see below) as follows: “A simple turn of the wrist makes these apple dumplings different from the common garden variety. After the edges of the dough are brought together over the sliced apple filling, the dumplings are turned over and placed in the baking dish, smooth side up. The results are delicious.”

Real Southern Apple Dumplings (1937)

Two cups soft wheat flour

1 teaspoon salt

½ cup shortening Cold water

4 or 5 tart apples

1 cup sugar

1 teaspoon cinnamon

2 tablespoons butter

Sift the flour and salt together; cut or rub the shortening into the flour with the tips of the fingers or a pastry blender; add water, a little at a time to make a very stiff dough. Do not knead. Roll the dough very thin. Cut in rounds (use a medium-sized saucer). Pare apples and slice thin. Place in the center of each round of pastry. Mix the sugar and cinnamon. Add 1 tablespoon to each dumpling. Moisten edges of pastry, bring together and seal. Place smooth side up in a greased baking dish. Prick tops, dot with butter and sprinkle with remaining sugar and cinnamon mixture. Add ¼ cup water, cover and bake in moderate oven (350 degrees F.) 30 minutes. Remove cover and brown pastry. Serve with whipped cream or lemon sauce. (Gibson 1937)

Marie Gibson was the first in a succession of important Courier-Journal food editors and writers that continues today. Collectively, they have influenced Kentucky foodways by introducing new recipes and food trends to their readers, but probably more important, they have served as mirrors, reflecting the innovative culinary practices of central Kentucky cooks back to their community. I discuss this further in later chapters.

Charity Cookbooks

Favorite Recipes (1938), compiled by the Woman’s Club of Louisville, is an early example of a cookbook with entertaining and parties in mind. The sales of the cookbook supported the club’s important social services program. The Woman’s Club of Louisville was established in 1890 and still occupies a large, historically significant building known as Frazier House. A pen-and-ink drawing of the front of Frazier House is included in the 1938 cookbook. A similar photograph dominates the first page of the group’s present-day website.

The cookbook includes, on page three, a poem apparently written by one of the members (signed E. B. R.). It reflects women’s growing social and economic engagement, yet their continued ties to the domestic sphere and traditional gender roles.

A woman likes to vote, she likes to make a speech;

She likes an office job, or else a school to teach;

She likes to do what men do—go fishing, fly a plane;

She likes to travel round the world, and come home again;

She likes to make what men can make, a picture, song, or book;

But in her very heart of hearts a woman is a cook;

So in this Club, where many minds compare their differing thought,

We’ve done the same for cooking each her specialty has brought.

The recipes, which are signed, list the ingredients first, followed by relatively extensive instructions, similar to what one might find in a contemporary cookbook. The measures used are modern, with a few exceptions such as “wine glasses.” Another modern feature is that degree settings for the oven are provided. Some recipes include serving advice in addition to the cooking procedure. For instance, the recipe for salmon croquettes notes that a can of mushroom soup can be used as the sauce.

Some recipes were provided by local eating establishments such as the Pendennis Club, a refined downtown Louisville social club that was established in 1881. Henry Bain sauce, which often appears in Louisville-focused cookbooks, was invented by a Pendennis Club headwaiter. Mrs. Isaac T. Woodson contributed the club’s recipe for turtle soup.

Pendennis Turtle Soup (1938)

2 pounds of veal bones

2 carrots

2 onions

1 ounce butter

3 tablespoons flour

2 quarts beef stock or water 1 small can tomatoes

1 small can tomato puree

salt

pepper

whole cloves

½ cup sherry

2 cups boiled fresh turtle meat

2 hard cooked eggs

Roast the bones and vegetables with butter until brown. Add water or beef stock, tomatoes, and tomato puree, salt, black pepper to taste and a few cloves. Boil for two hours. Add sherry wine, strain the soup through cheese cloth. Then add the boiled fresh turtle meat, cut in small squares, and eggs also in small squares. Boil up quickly and serve. (Woman’s Club of Louisville 1938, 156–57)

Branded food products are called for relatively frequently. These brands include Philadelphia cream cheese, Fleischman’s yeast, Crisco shortening, Baker’s chocolate, Dromedary dates, Brer Rabbit molasses, Swans Down cake flour, None-Such mincemeat, Karo syrup, Wesson oil, Knox gelatin, Jell-O gelatin dessert, Kraft mayonnaise, Campbell’s tomato soup, and Kraft Velveeta cheese. It is likely that the recipes using these products were originally published in magazines or in company-issued pamphlets.

Mrs. J. G. Minnigerode contributed the following recipe for scalloped oysters.

Scalloped Oysters (1938)

1 pint oysters

4 tablespoons oyster liquor

2 tablespoons milk or cream

½ cup stale bread crumbs

1 cup cracker crumbs

½ cup melted butter

Salt and pepper

Mix bread and cracker crumbs, and stir in butter. Put a thin layer in bottom of a buttered shallow baking dish, cover with oysters, and sprinkle with salt and pepper; add one-half each oyster liquor and cream. Repeat, and cover top with remaining crumbs. Bake thirty minutes in hot oven. Never allow more than two layers of oysters for Scalloped Oysters; if three layers are used, the middle layer will be underdone, while others are properly cooked. A sprinkling of mace or grated nutmeg to each layer is considered by many an improvement. (Woman’s Club of Louisville 1938, 90)

The recipes selected for this cookbook no doubt addressed the club members’ needs, which apparently included advice on entertaining. This is certainly one of the earliest Kentucky cookbooks with a section on entertainment. In a sense, this cookbook could have served as a prototype for later cookbooks such as the Junior League of Louisville’s The Cooking Book (1978). By the mid-1950s, there were cookbooks focused entirely on entertainment, such as Marion Flexner’s Cocktail Supper Cookbook (1955). Later examples include the Younger Woman’s Club of Louisville’s Party Cook Book (1966) and the Queen’s Daughters’ Entertaining the Louisville Way (1969).4 More recently, Sarah Fritschner, former food editor of the Courier-Journal, published two entertainment-focused cookbooks with a Kentucky Derby theme: Derby 101: A Guide to Food and Menus for Kentucky Derby Week (2004) and Sarah Fritschner’s Derby: Start to Finish (2006).

Prohibition Repealed!

The Depression era brought a change in the legal status of alcoholic beverages. The Volstead Act, passed in 1919, had many negative and largely unintended consequences and was repealed with passage of the Twenty-First Amendment in 1933. One response to the repeal of Prohibition was the publication of recipe books for cocktails and other drinks, such as Irvin S. Cobb’s Own Recipe Book (1936). Cobb, a nationally known humorist from Paducah, wrote newspaper columns, short fiction, and screenplays, and he was the emcee of the 1935 Academy Awards. Cobb died in 1944 and is buried in his native Paducah. The publisher of Cobb’s book, Frankfort Distilleries, produced both blended and straight whiskeys under various brands, including Four Roses (still on the market) and Old Oscar Pepper and Kentucky Velvet (no longer available). The recipe book includes a long essay by Cobb on whiskey in general and bourbon in particular, along with seventy-one recipes for cocktails and other drinks, with commentary by Cobb. There is also an essay on the history of Frankfort Distilleries, with considerable emphasis on how it followed the law during the Prohibition era: “During Prohibition, Frankfort sold only though legal channels. So far as is known, no Frankfort whiskey was ever bootlegged” (Cobb 1936, 37). Frankfort Distilleries held a federal distiller’s permit, which allowed it to make medicinal whiskey. As the copy states, “In one year, more than 20,000 physicians purchased Frankfort whiskies for office use. One Frankfort brand, Antique, became known as the finest medicinal whiskey made” (ibid., 36).

Cobb includes a recipe for the old-fashioned, and he repeats the myth of its Pendennis Club origins, which has become conventional knowledge but is disputed by some. He asserts, “This cocktail was created at the Pendennis Club in Louisville in honor of a famous old-fashioned Kentucky colonel. I claim it is worthy of him” (Cobb 1936, 41). The legend is that the drink was originally created by a Pendennis Club bartender and promoted by the famous distiller Colonel James E. Pepper. Cocktail guide writer David Wondrich (2007) deflates the story by reporting that the old- fashioned cocktail was mentioned in the Chicago Tribune before the Pen- dennis Club was founded in 1881. In The Old Fashioned: An Essential Guide to the Original Whiskey Cocktail, Albert W. A. Schmid (2013) recounts the history of this classic and creates a place for the Pendennis origin legend by referring to the old-fashioned “as we know it today.” Schmid’s book contains many recipes for the old-fashioned, including a version of Cobb’s that includes curaçao, which I don’t recall seeing in any other recipes for this classic. The basic strategy, however, is the same: muddle bitters and a cube of sugar, add bourbon and a twist of citrus (most likely lemon), and then garnish with fruit, such as a slice of orange, a maraschino cherry, or perhaps pineapple. Some like to add a splash of club soda or sweet soda.