Dixie Dishes, the first narrative Kentucky cookbook.

CHAPTER FIVE

World War II

World War II had an impact on Kentucky cookbooks and recipes. The most important influence was the dramatic increase in women’s participation in the labor force, making convenience and efficiency paramount. These issues began to appear in the 1940s and certainly became more common in cookbooks of the 1950s and 1960s. Convenience was also promoted when, after the restrictions of the war years, the nation’s robust industrial capacity and pent-up consumer demand led to the widespread use of kitchen appliances such as refrigerators and freezers.

Cookbooks and recipes of the era were shaped, to an extent, by war-time food policies such as rationing. This resulted in the introduction of new foods that were often replacements for rationed items. Also new in the 1940s were Kentucky cookbooks that attempted to tell a story beyond the recipes. In addition, this was the period when Bowling Green’s own Duncan Hines published his innovative cookbooks and guides to fine dining.

Cookbooks that Tell a Story

Starting in the early 1940s, some cookbook authors embellished their recipes by including stories about the food, its historical context, the persons who cooked it, and the farmers or artisans who produced it; discussions of the finer technical points of food preparation; and, most of all, recollections about eating the food. The effect of these narratives was to create a web of meaning that enhanced the eating and cooking experience. In a phrase, it made food “good to think,” to borrow an idea from anthropologist Marvin Harris (1985). The narrative was built primarily with textual material on various topics but also with the use of creative titles, images and their accompanying captions, and an occasional sidebar. Certainly this increased the pleasure associated with reading cookbooks and encouraged people to collect them. These days, most single-author cookbooks attempt to tell a story in conjunction with each recipe, and some express a consistent theme. Robust narratives appeared much later in the history of community charity cookbooks, but today they are quite common in more elaborately produced examples.

The earliest examples of narrative cookbooks are two by Louisville food writer Marion W. Flexner: Dixie Dishes (1941), published in Boston, and Out of Kentucky Kitchens (1949), published in New York. Dixie Dishes appears to be the first true narrative cookbook among those considered here. Flexner’s later volume makes similar use of the narrative style. John Egerton comments about Out of Kentucky Kitchens, “In a state noted for its cuisine and its cooks, this little volume holds a place of honor” (1993, 360–61). My mother gave me a copy of this classic cookbook when my family first moved to Kentucky in 1974, and it served as my introduction to Kentucky cuisine. It is still available in the form of a University Press of Kentucky reprint (Flexner 1989). Dixie Dishes is very similar but is less well known than the later book. Flexner’s other cookbooks include Food for Children and How to Cook It (1929; cowritten with Isabel McLennan McMeekin), Quick Cooking from the Top of the Stove (1951), and Cocktail Supper Cookbook (1955). She started writing with a Louisville women’s writing group, which led to the submission of articles to the Courier-Journal. Her literary endeavors went beyond cookbooks and included a biography of Queen Victoria for young adults entitled Drina: England’s Young Victoria (1939) and a book on gardening. Apparently, Flexner’s mother also wrote cookbooks.

Marion W. Flexner was born in Montgomery, Alabama, and married Morris Flexner, a Louisville physician. I think Dixie Dishes is the first of the southern food cookbooks with clear Kentucky roots, although it has a very strong Gulf coast–New Orleans content. Both Dixie Dishes and Out of Kentucky Kitchens provide detailed recipes for basic Kentucky-style country cooking, among other themes. Flexner’s experiences in New Orleans are reflected in recipes for king cake, pralines, and various Creole dishes. In addition to her cookbooks, Flexner combined her interests in food, cooking, and writing by contributing articles to the New Yorker, Harper’s, Vogue, Woman’s Day, House and Garden, and Gourmet.

Dixie Dishes, the first narrative Kentucky cookbook.

Although Flexner presents her recipes in the modern format found in today’s cookbooks, some of the recipes apparently originated from those “cooked by ear” by the African American cooks who worked in Flexner’s girlhood homes (Flexner 1941, x). Like Jennie C. Benedict, she learned a great deal from the African Americans that served her family. She recalled, “I suppose it was to keep me employed during the long period after breakfast that ‘Aunt Fanny’ my grandfather’s colored cook, would slip one of her large crisp white aprons over my head and set me to work. As I grew older she taught me many other ‘intangibles’ of cooking—the ‘feel’ of different types of dough, the cook and taste method of making sauces, the secret of adding charred onions to gravies for roasts” (ibid., dust cover). When Flexner shares what she learned from these African American cooks, her cookbook becomes biographical. Here and there she re-creates these scenes from her girlhood with a respectful but patronizing tone. For instance, Flexner relates an incident in which the family cook, Molly, gives Flexner’s aunt a recipe but leaves out some vital ingredients. Young Marion wondered about this. “‘Why did you do it?’ I asked. I didn’t dare scold Molly—nobody did.” Molly responded: “‘Lissen chile,’ she said seriously, shaking her finger at me, ‘dat pie is ma specialty—see? Effen Ah gives my receipts to everybody what axes for ’em, what Ah gwine ter lef’ ter surprise ’em wid?’ She put her hand kindly on my arm. ‘Ah’ll give you a piece of advice from an ol’ woman—always keep sumpin’ in reserve what you kin do better’n ennybody else, and don’ share dat secret wid no one’” (ibid., 125–26).

In addition to recipes from the cooks who worked in her household, Flexner provides recipes from her mother, friends, some restaurants, and, in Out of Kentucky Kitchens, recipes from hard-to-find Louisville cookbooks. Here, I discuss two of these cookbooks on which Flexner drew: Random Recipes by Minn-Ell Sherley Mandeville (1940) and Query Club Recipes (Allen 1941). Both include recipes for iconic Kentucky foods such as burgoo, fried chicken, greens, country ham, mint juleps, and various pies. Because she was writing for a national audience, Flexner includes recipes for traditional preparations that were taken for granted and rarely included in earlier Kentucky-based cookbooks.

Dixie Dishes and Out of Kentucky Kitchens are rooted in the Kentucky-inflected version of southern cooking. Perhaps even more clearly than Mary Harris Frazer’s Kentucky Receipt Book (1903), Flexner clearly shows the basics of Louisville foodways—a foundation of simple Kentucky foods of rural origin coupled with strong Gulf coast influences and a sprinkling of European (mostly German and some French) tendencies. Given the region’s cultural and culinary inclusiveness, recipes representative of various ethnic cuisines often show up in cookbooks rooted in Louisville. This is associated with a good-natured interest in food, dining out, and entertaining, especially at Derby time.

Introducing basic country cooking to her Dixie Dishes readership required detailed procedures and a narrative that conveyed the cultural context. It makes sense that this early account of basic Kentucky cuisine came from a person with a cosmopolitan viewpoint writing for a national audience. Included here is Flexner’s recipe for a cabbage dish that she describes as the “traditional Southern recipe of preparing cabbage,” which “screams for corn pone” to dunk in the pot likker. She notes that a dash of apple cider vinegar can be added at the table.

Cabbage with Salt Pork or Country Bacon (1941)

1 head, hard, white cabbage

1 slice hot red pepper

Salt, pepper to taste

½ pound bacon or salt pork

Water to cover cabbage

Put all ingredients on the stove in a heavy iron pot with a tight fitting lid. Wash the salt pork before using it. Cook 2 hours or until the liquor is full flavored and the cabbage tender. If salt pork is used, no extra salt will be necessary. The cabbage is likely to turn brown, but no matter.

Flexner goes on to say, “This is a fine luncheon dish for the laundress or the thorough cleaning men, and for you too, if you like it” (1941, 77–78).

Recipes of this era include more detailed discussions of technique than did previous cookbooks. One might attribute this to a decrease in readers’ knowledge of cooking. As more women entered the workforce, they had fewer “apron-string cooking classes,” and the amount of time they could devote to cooking decreased. The ingredients-only recipes found in community cookbooks from the turn of the century disappeared, and procedures were described in greater detail. Further, cooks and the people they cooked for were more cosmopolitan and adventuresome in their tastes, and cooks needed more elaborate information to produce authentic versions of new dishes. Certainly, Louisville-based cookbooks contained a number of ethnic dishes. The two Flexner cookbooks were clearly written for a sophisticated national audience that would be unfamiliar with the iconic dishes of southern cuisine, seeing them as exotic rather than commonplace. She assumes her readers have never heard of pot likker and think that cornmeal is always yellow. She therefore provides extensive discussions of technique, and, given Flexner’s effective and entertaining prose, this makes for interesting reading.

Flexner draws on the rare and “oh so Louisville” Random Recipes by Minn-Ell Sherley (aka Mrs. Fulton) Mandeville (1940). Mandeville was a prominent Louisville club woman, and her Random Recipes, published in proper letterpress and hard cover, consists of recipes that “have been used up and down ‘The River’ for generations” (Mandeville 1940, n.p.). Although it includes a wide range of dishes, they are often placed randomly; for example, the Bluegrass classic beaten biscuits shares a page with the gourmet flambéed dessert crepes suzette (ibid., 3). Like many Louisville cookbooks, there is some evidence of entertaining, including a whole section on hors d’oeuvres. Mandeville’s recipe for persimmon pudding appeared in many editions of Kentucky Heritage Recipes (Historic Homes Foundation 1976, 59). Unfortunately, the Mandeville volume contains limited narrative beyond the basics of the recipe. Nevertheless, she makes some comments. For instance, her recipe for corncakes ends with the following advice: “Use only white corn meal and never, never put sugar with it. That is an unpardonable sin in the South” (Mandeville 1940, 1). And in concluding her recipe for boiled calf’s head, she writes what seems to be a non sequitur: “The best country hams I have ever tasted come from Cadiz, Kentucky. The late King of England was a regular customer” (ibid., 54). Here is her recipe for bread pudding.

Bread Pudding (1940)

3 slices of bread

1 quart cream

1 scant cup sugar

4 eggs

1 teaspoon vanilla

Let bread soak in cream ½ hour. Add well beaten yolks, sugar and vanilla. Lastly add the stiffly beaten whites. Bake in moderate oven 2 hours or more. Serve with hard sauce flavored with whiskey or sherry. (Mandeville 1940, 23)

Flexner’s Out of Kentucky Kitchens includes recipes for “Minn-Ell Mandeville’s Famous Spinach Farmers’ Special” and “Minn-Ell Mandeville’s Transparent Pie” (Flexner 1949, 149, 219). Flexner pays tribute to Mandeville, calling her “one of the best cooks Kentucky ever produced” (ibid., 219).

Another cookbook used by Flexner is a pamphlet titled Query Club Recipes, a compilation of members’ recipes published in 1941. The Query Club, described by Flexner as “a small, select Louisville literary group” (1949, 244), consisted of the wives of some of the most important and wealthiest men in Louisville. Many of the recipes, which are signed, are typical of upper-class Louisville society; however, a few are typically Kentuckian, such as country ham. Some Gulf coast favorites are also included, such as chicken gumbo. The members’ international orientation and travel experiences are evident in recipes for crème brûlée, borscht, and “Singapore’s Famous Million Dollar Cocktail.” The contributor notes that the cocktail recipe was “given me by the brother of the man who makes them there at Raffle’s Hotel” (Allen 1941, 19). Out of Kentucky Kitchens includes two Query Club recipes, which Flexner titles “Dr. Alice Pickett’s Bishop’s Bread or Buttermilk Coffee Cake” and “Query Club Sponge Pudding with Wine Sauce.” In the Query Club pamphlet, Pickett adds this comment about the recipe’s origin: “This Southern type of coffee bread was so often served for Sunday breakfasts—in the Bluegrass, the Carolinas and Virginia—to any visiting ‘bishops, priest, deacons and other clergy’ that it came to be known as ‘Bishop’s Bread’” (ibid., 31).

Bishop’s Bread (1941)

2 ½ cups flour

½ cup shortening

2 cups medium-brown sugar

1 teaspoon baking powder

½ teaspoon soda

½ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon cinnamon

1 egg

¾ cup sour milk

Mix flour, salt, brown sugar and shortening, saving nearly a cup of the mixture for sprinkling on top of bread. To the rest of the mixture add baking powder, egg, sour milk, soda and cinnamon. Beat thoroughly. Put batter into two well-greased cake pans, sprinkling the first mixture over the tops. (Extra cinnamon may be added to the sprinkling mixture.) Bake in a hot oven about 25 minutes. Cut in squares or strips and serve piping hot, with lots of butter. (The second pan of bread may be used the next day, after a reheating in the oven.) (Allen 1941, 31)

On the Road with Duncan Hines

Another important person in the culinary history of Kentucky was Duncan Hines, who later became famous for his cake mixes and other grocery items. Born in Bowling Green, he worked as a traveling salesman for a printing company, and while he was on the road, he ate out a lot and started to compile lists of his favorite restaurants in various parts of the county. In 1935 he prepared a list of several hundred good restaurants and distributed it with his Christmas cards. The response was so positive that he continued the project, and updated editions of his guidebook Adventures in Good Eating were published into the early 1960s. In 1939 Hines published the first of his annually updated cookbooks called Adventures in Good Cooking. This was followed in 1955 with the Duncan Hines Dessert Book. Versions of both cookbooks were republished in 2002 under the editorship of his primary biographer, Louis Hatchett. The recipes came mostly from restaurants throughout the United States and Canada, such as the one for deviled crab from the Tarpon Inn in Port Aransas, Texas. Other recipes came from individuals, including a few from Kentuckians, almost all of them from Bowling Green. A portion of the Kentucky recipes are for iconic dishes such as spoon bread, fried chicken, pot liquor, burgoo, fried apples, chess pie, and fried corn. The following recipe for graham cracker pie (recipe 445 in the 1948 edition) is from the only Kentucky restaurant included in the book: Sanders Café in Corbin. The cookbook uses an idiosyncratic two-column format combined with an action format, reminiscent of The Joy of Cooking. I simplified the format here.

The Duncan Hines cookbook.

Graham Cracker Pie (1948)

Crust |

|

Ingredients |

|

30 graham crackers, crushed |

½ cup sugar |

2 tablespoons flour |

1 cup melted butter |

2 tablespoons cinnamon |

½ cup lard, melted |

Directions (Makes two 8-inch pies)

Mix all ingredients and press in pie pans.

Filling |

|

Ingredients |

|

1 quart milk |

½ cup sugar |

8 egg yolks, beaten |

8 egg whites, beaten |

4 tablespoons cornstarch |

½ cup sugar |

2 teaspoons vanilla |

1 pinch of salt |

Pinch of salt |

1 teaspoon vanilla |

2 tablespoons melted butter |

|

Directions

Heat milk.

Mix egg yolks, cornstarch, vanilla, salt, butter, and ½ cup sugar; add the heated milk and cook until thick. Then fill the pie shells.

Make a meringue of remaining ingredients and cover pies. Brown in 350° oven. (Hines 1948, 445)

Based on his reputation and name recognition, Duncan Hines started a branded grocery business with businessman Roy Park. This enterprise was bought by Procter and Gamble in 1956, which added cake mixes to the offerings. Although this business has changed ownership through the years, Pinnacle Foods still sells Duncan Hines cake mixes and frostings. The Bowling Green Junior Women’s Club is the current sponsor of the annual Duncan Hines Festival, held in July. The program includes a concert and a baking contest using Duncan Hines products, sponsored by Pinnacle Foods.

The War and Rationing

World War II had a considerable impact on foodways. Food rationing and related food shortages had important impacts that led to the creation of new recipes and the substitution of scarce ingredients with others that were more readily available.1 Further, the war itself led to the appearance of new food products that grew out of the need to feed the troops.

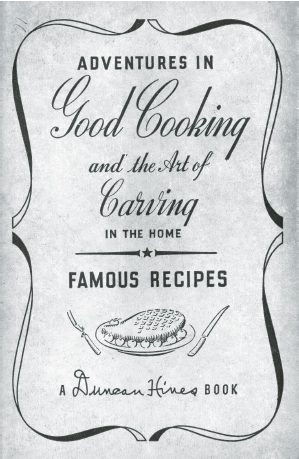

Rationing was administered by the Office of Price Administration (OPA) through a coupon-based system. Starting in early 1942, each person received a series of war ration books filled with little perforated stamps, or coupons, coded for various categories of commodities. When rationed foods were purchased, the buyer paid with both money and ration coupons, which had to be torn off in the presence of the grocer to help prevent fraud. Different items required a different number of ration coupons (or ration points); for instance, a measure of beef roast cost more ration points than the same measure beef organ meats. Initially, no change was given for ration coupons; however, by 1944, small plastic disks were used as change. The coupons had expiration dates, adding to the complexity of household management. Food buyers, in effect, had to juggle two kinds of money. Along with the rationing effort, the OPA administered a system of price controls. Rationing lasted beyond the war, and the OPA was finally abolished in May 1947.

Rationed food items included sugar, coffee, meats, canned fish, cheese, canned milk, processed meats (sausage), dried and canned beans, prepared baby foods, and edible fats (including butter, lard, margarine, shortening, and the various oils). The rationing of sugar started early and lasted the longest (until 1947, well after the war ended). Because sugar was a special concern, there were special sugar coupons. The Japanese conquest of the Philippines early in 1942 was the initial crisis that led to sugar rationing. Beyond this, the problem with sugar was that a large portion of it was produced offshore and had to be imported, taking up space on cargo ships that was better allocated to troops and war materiel. Although rationing had some impact on the few cookbooks published during the war, there were recipes that called for sugar and other rationed foods. Foods that were not rationed included eggs, fresh fish, bread, cereal, pasta, mayonnaise, jams and jellies, fresh milk, and cottage and cream cheeses. Canned goods were rationed because of the need to conserve metal. Nonfood items were also rationed, including gasoline, fuel oil, kerosene, cars, tires, shoes and rubber footwear, and even typewriters.

Farmers and others were able to consume anything they produced themselves, and they also received their full share of ration points. Farmers who raised and slaughtered meat animals had to file for a permit if they intended to sell the meat. And farmers who sold rationed commodities directly to consumers had to collect coupons from them.

Cooks adapted. In Theatrical Seasonings, which reprints some recipes from a war-era cookbook, Mrs. E. E. Freeman notes, “It was during the war when so many things were rationed, so we used recipes that were inexpensive, yet delicious” (Winchester Council for the Arts 1994, 6). A contemporary community cookbook, Preserving the Past for the Future published by the Hopkins County Genealogical Society (2011), reprints portions of The Victory Handbook for Health and Home Defense.2 Included are some suggestions for saving sugar: “As a first help in keeping within your sugar quota, try using less sugar in puddings, gelatins, ice creams, etc. You may find you have been adding more sugar than you need” (Hopkins County Genealogical Society 2011, n.p.).

Rations coupons distributed by the Office of Price Administration during World War II.

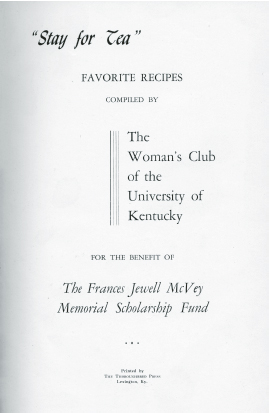

A number of unrationed ingredients could substitute for sugar, including honey, sweet sorghum syrup, and corn syrup.3 Corn syrup was not a wartime invention; sweetener from corn was first manufactured in 1866, and the familiar Karo syrups were introduced in 1902. Corn syrup appears in a number of recipes in Stay for Tea, one of the most interesting Kentucky fund-raising cookbooks of the 1940s. The University of Kentucky Women’s Club published Stay for Tea (1948) to raise money for a scholarship fund established to honor Mrs. Frank McVey, whose husband was president of the university. She was very involved in programs that supported the university and did a considerable amount of entertaining on its behalf. Like most community cookbooks of the time, Stay for Tea has little narrative accompanying the member-contributed recipes. Al-though published after the war, Stay for Tea includes some recipes that reflect the wartime food situation, new food products, and availability of new technology. (Updated versions of Stay for Tea were published in 1975, 1983, and 2010; see chapter 8.)

Stay for Tea has five recipes for brownies, two of which use corn syrup. By the way, one of the brownie recipes was submitted by Esther (Mrs. A. F.) Rupp, wife of legendary Kentucky basketball coach Adolph Rupp. A sugarless recipe for brownies was contributed by Mary L. (Mrs. H. H.) Jewett.

The first of the Stay for Tea cookbooks, published in 1948.

Sugarless Brownies (1948)

½ cup shortening

1 cup white corn syrup

2 squares unsweetened chocolate, melted

¾ cup sifted cake flour

1 teaspoon vanilla

¼ teaspoon baking powder

¼ teaspoon salt

2 eggs, well beaten

¾ cup chopped nuts

Cream shortening until fluffy, then add corn syrup gradually, continuing to work with spoon until light. Stir in melted chocolate. Sift together dry ingredients and add ¼ of them while beating mixture. Add well-beaten eggs, then remainder of dry ingredients and nuts. Turn into greased 9×9×3 inch cake pan and bake in 350 degree oven for about 35 minutes. Cut into squares when done. Makes 25. (University of Kentucky Women’s Club 1948, 125)

Rationing created an incentive to use prepared mixes rather than baking from scratch. However, under the OPA, manufacturers’ sugar supplies were also rationed, based on a percentage of their use levels prior to rationing. Another remedy for sugar rationing was to take advantage of the sugar contained in processed foods. Selected Recipes from the Blue Grass, published by the United Christian Missionary Society of the Christian Church of Midway in 1944, includes a recipe for a sweet dessert that calls for no sugar at all. Instead, it makes use of marshmallows and the syrup or juice from canned pineapple.

Pineapple Dessert (1944)

One number 2 can of sliced pineapple. Dip slices from syrup. Heat syrup in double boiler. When hot, but not boiling stir this into a pound of fresh marshmallows. Cut slices of pineapple into small pieces and stir in. Let cool thoroughly, then take a half pint of cream whipped stiff. Stir in gently, chill and serve. Will serve about 8. (Christian Church 1944, 33)

A few recipes always contained corn syrup, even before sugar rationing. One of these is pecan pie—a classic southern dessert. Some even say that the recipe was created by the Karo test kitchens in the 1920s.

Pecan Pie (1944)

3 eggs

1 cup white sugar

1 cup dark Karo syrup

1 cup broken pecans

¼ teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon vinegar

Beat eggs, stir sugar in well, add syrup, salt, vanilla, vinegar, and lastly pecans. Pour in uncooked crust and bake 45 minutes in medium oven. This makes a pie to serve six. (Christian Church 1944, 33)

In addition to ingredient substitutions, such as the corn syrup for sugar swap, Stay for Tea introduced a new food product: Spam. The canned chopped pork product was first produced in 1937 by the Hormel Company of Austin, Minnesota, largely to make use of the pork shoulders that were a residue of its ham business. The name Spam was the result of a naming contest, and it is believed to be a contraction of spiced ham. Because it does not require refrigeration, Spam became an important item in the diets of U.S. servicemen and Allied troops during World War II. Following the war, sales soared. Hormel has expanded the Spam product line with different flavors and ingredients. Based on the success of Spam, Armour produced a similar product named Treet, which some regard as inauthentic. Stay for Tea’s Spam recipe was contributed by Opal Palmer.

Beans ’n Spam (1948)

2 cans baked beans

1 can Spam

6 teaspoons (or more) prepared mustard

¼ cup brown sugar

2 tablespoons New Orleans molasses

2 teaspoons ground allspice

Empty the beans into a glass baking dish, slice Spam in six pieces and arrange on top of beans. Score the Spam two ways with sharp knife. Make a paste of prepared mustard, brown sugar, molasses and allspice and cover Spam slices with it. Bake [at] 350 degrees for 40 minutes. (University of Kentucky Women’s Club 1948, 216)

Refrigeration Comes to Kentucky Homes

The post–World War II period saw the widespread adoption of refrigerators to replace iceboxes. Refrigerators were first made in about 1915 and became available for home use in the 1920s, but market penetration was limited. For the most part, these refrigerators were electric, but there were also gas-powered models on the market. Like all technological innovations, there was a long interval between early adopters of mechanical refrigeration and later ones, and it took a while for iceboxes to be replaced completely. Interestingly, rural residents who lived near railroad stops were able to have ice delivered regularly. Many brands of refrigerators were available in the early day, including Kelvinator, Frigidaire, and the widely used General Electric Monitor Top.4

With refrigeration came an increase in recipes involving chilling. To illustrate, Marion Flexner has this to say about “Ollie’s Ice Box Super Rolls”: “Since Ollie, our substitute cook, confided to me the recipe for her ice box rolls, I have practically discarded all other roll recipes. For this is without a doubt the greatest boon to housekeeping I have had in years. The dough will keep for several weeks in the electric refrigerator (provided it is not defrosted in the meantime). It lends itself to all possible variations” (1941, 13).

The 1948 version of Stay for Tea has a number of recipes that require refrigeration, including a large section on frozen desserts. Note that the term icebox is still used in recipes today.

Icebox Cookies (1948)

1 cup butter

2 cups brown sugar

2 whole eggs

3 ½ cups flour

1 teaspoon salt

¾ cup pecans

Cream butter and sugar. Add beaten eggs, flour and salt, a little at a time. Add pecans. Shape in roll, wrap in waxed paper and place in ice-box over night. Slice thin and bake in moderate oven. (University of Kentucky Women’s Club 1948, 138)