Sectional conflict, or growing tensions between northern and southern states, mounted from 1845 to 1860 as the main fault lines in American politics shifted from a partisan division (Whigs versus Democrats) to a geographical one (North versus South). In broad terms, a majority of northern and southern voters increasingly suspected members of the other section of threatening the liberty, equality, and opportunity of white Americans and the survival of the U.S. experiment in republican government; specific points of contention between northern and southern states included the right of a state to leave the federal union and the relationship between the federal government and slavery. Constitutional ambiguity and the focus of both the Whig and Democratic parties on national economic issues had allowed the political system to sidestep the slavery issue in the early nineteenth century, but the territorial expansion of the United States in the 1840s forced Congress to face the question of whether or not slavery should spread into new U.S. territories. The pivotal event that irreversibly injected slavery into mainstream politics was the introduction of the Wilmot Proviso in Congress in August 1846. The slavery extension issue destroyed the Whig Party, divided the Democratic Party, and in the 1850s, enabled the rise of an exclusively northern Republican Party founded to oppose the westward expansion of slavery. When Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election of 1860, his victory precipitated the immediate secession of seven states, the eventual secession of four more states, and a Civil War that lasted from 1861 to 1865.

Beginning with the annexation of Texas in 1845, the rapid acquisition of western territories stoked sectional conflict by forcing Congress to face the question of slavery’s expansion into those new territories. In prior decades, the two dominant national parties, the Whigs and the Democrats, relied on the support of both northern and southern constituencies and courted voters by downplaying slavery and focusing on questions of government involvement in the economy. Before 1845, expansion, much like support for tariffs or a national bank, was a partisan rather than sectional issue, with Democrats championing and Whigs opposing the acquisition of territory, but the annexation of Texas set in motion of series of events that would eventually realign loyalties along sectional contours.

A Mexican state from the time of Mexican independence in 1821, Texas was settled largely by white American Southerners who chafed against the Mexican governments abolition of slavery in 1829 and broke away to form the Republic of Texas in 1836. The 1836 Treaty of Velasco between the Republic of Texas and General Antonio Lopez De Santa Ana of Mexico named the Rio Grande as the border between Texas and Mexico. But the Mexican Congress refused to ratify that boundary because the Nueces River, far to the North of the Rio Grande, had been the southern limit of Texas when it was a Mexican state, and redrawing the border at the Rio Grande gave thousands of miles of Mexico’s northern frontier (the present-day southwest) to Texas. Almost immediately, Americans in Texas began to press for the admission of Texas into the Union. When the United States annexed Texas in 1845, it laid claim to land between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande, which Mexico still regarded as part of Mexico, thus provoking a boundary dispute between the United States and Mexico. American president James K. Polk, an ardent Democrat and expansionist, ordered U.S. troops under General Zachary Taylor to the banks of the Rio Grande, where they skirmished with Mexican forces. Pointing to American casualties, Polk asked Congress to approve a bill stating that a state of war existed between Mexico and the United States, which Congress passed on May 12, 1846.

Militarily, the Mexican-American War seemed like an easy victory for the United States, but international context and domestic politics helped make the war a spur to sectional disharmony. According to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, negotiated on February 2, 1848, and announced by President Polk to be in effect on July 4 of that year, the United States was to assume debts owed by the Mexican government to U.S. citizens and pay the Mexican government a lump sum of $15 million, in exchange for which it would receive Texas to the Rio Grande, California, and the New Mexico territory (collectively known as the Mexican Cession). Public opinion was shaped in part by differing American reactions to the revolutions of 1848 in Europe, with some Americans interpreting the European blows for liberal democracy as mandates for the expansion of American-style democracy via territorial acquisition, while others (primarily in the North) viewed conquest as the abandonment of democratic principles. Reaction was even more acutely influenced by developments within the Democratic Party on the state level. While the annexation of Texas and the war with Mexico were generally popular among the proexpansion Democratic Party in the northern as well as southern states, fear that the party was being turned into a tool for slaveholders began to percolate with the annexation of Texas and intensified in response to the war with Mexico. In New Hampshire, for example, loyal Democrat John P. Hale denounced Texas annexation and broke with the state organization to form the Independent Democrats, a coalition of antislavery Democrats, dissatisfied Whigs, and members of the Liberty Party (a small, one-issue third party formed in 1840) that grew strong enough to dominate the New Hampshire legislative and gubernatorial elections of 1846. In New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio, some Democratic voters grew increasingly worried that President Polk had precipitated the war with Mexico specifically to expand slavery’s territory. In hopes of quelling such fears, Pennsylvania Democratic congressman David Wilmot irrevocably introduced slavery into political debate in August 1846 with the Wilmot Proviso.

Wilmot introduced his proviso when Polk asked Congress for a $2 million appropriation for negotiations with the Mexican government that would end the war by transferring territory to the United States. Wilmot added an amendment to the appropriations bill mandating that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever exist” in the territories gained from Mexico. The proposed amendment did not end slavery anywhere (slavery was illegal under Mexican law in the territories in question), but it did attempt to curb slavery’s extension, and from that time on, the slavery expansion question dominated congressional debate and fueled sectional conflict. With the support of all northern Whigs and most northern Democrats, and against the opposition of all southern Democrats and Whigs, the Wilmot Proviso passed in the House of Representatives but failed in the Senate.

Outside of Washington, D.C., the impact of the Wilmot Proviso escalated in 1847 and 1848. By the spring of 1847, mass meetings throughout the South pledged to oppose any candidate of any party who supported the Proviso and pledged all-southern unity and loyalty to slavery. In the North, opinion on the Proviso was more divided (in politically powerful New York, for example, the Democratic Party split into the anti-Proviso Hunkers and pro-Proviso Barnburners). But the same strands that had come together to form the Independent Democrats in New Hampshire in 1846 began to interweave throughout the North, culminating in the Buffalo National Free Soil Convention of 1848, a mass meeting attended by delegates elected at public meetings throughout the northern states.

An incongruous mix of white and black abolitionists, northern Democrats who wanted no blacks (slave or free) in the western territories, and disaffected Whigs and Democrats, the Buffalo convention created a new political party, the Free Soil Party, based on a platform of “denationalizing slavery” by barring slavery from western territories and outlawing the slave trade (but not slavery) in Washington, D.C. Adopting the slogan, “Free Soil, Free Speech, Free Labor, and Free Men,” the Free Soil Party nominated former Democrat Martin Van Buren as its candidate for the 1848 presidential election. Van Buren did not win (Zachary Taylor, a nominal Whig with no known position on the slavery extension issue became president), but he did get 10 percent of the popular vote. In addition, 12 Free Soil candidates were elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. In Ohio, 8 Free Soilers went to the state legislature, where they repealed Ohio’s discriminatory “black laws” and sent Free Soiler Salmon P. Chase to the Senate. In all, the emergence of the Free Soil Party weakened the existing two-party system even as it signaled growing northern disinclination to share the western territories with slaves and slaveholders.

The growth of Free Soil sentiment in the North worried many moderate southern voters, who grew alarmed that the nonextension of slavery beyond its current limits would eventually place the slaveholding states in a minority in the Union as more free states entered and tipped the current balance. A radical group of southern separatists known as the Fire Eaters and led by men such as William Yancey, Edmund Ruffin, and Robert Barnwell Rhett, gained influence as moderates’ concern over permanent minority status grew. The Fire Eaters succeeded in convincing all slaveholding states to send delegates to a formal southern convention to meet in Nashville, Tennessee, on June 3, 1850, where delegates would discuss strategies for combating growing hostility to slavery, including secession from the Union. The Nashville Convention asserted the southern states’ commitment to slavery and assumed the rights of a state to secede if its interests were threatened, but the convention also affirmed that slavery and southern interests were best served within the Union, as long as Congress met a series of conditions. Conditions included rejection of the Wilmot Proviso, a prohibition against federal interference with slavery in Washington, D.C., and stronger federal support for slaveholders attempting to reclaim slaves who had escaped to free states. The convention agreed to reconvene after Congress had resolved the slavery extension issue to determine if the solution met its conditions.

While opinion hardened in House districts, Congress tackled the question of slavery’s fate in the Mexican Cession. Four possible answers emerged. At one extreme stood the Wilmot Proviso. At the opposite extreme stood the doctrine, propagated by South Carolinian and leading southern separatist John C. Calhoun, that “slavery followed the flag” and that all U.S. territories were de facto slave territories because Congress lacked the right to bar slavery from them. A possible compromise, and third possible approach, was to extend the Missouri Compromise line all the way to the Pacific, banning slavery from territories north of the 36° 30’ line, and leaving territories south of that line open to the institution; this approach would permit slavery in the Mexican Cession. A final possibility (the favorite of many northern Democrats) was to apply the principle of “popular sovereignty,” which would permit voters living in a territory, and not Congress, to determine if slavery would be allowed in the territory; noted adherents such as Lewis Cass and Stephen Douglas did not specify if voters would determine slavery’s fate at the territorial or statehood stage.

The Nashville Convention and the urgent press to admit California to the Union following the discovery of gold in 1849 forced Congress to cobble together the Compromise of 1850. An aging Henry Clay, whose brand of compromise and Whig Party were both wilting as the political climate relentlessly warmed, submitted an omnibus compromise bill that admitted California as a free state, barred the slave trade in Washington, D.C., threw out the Wilmot Proviso, and enacted an unusually harsh Fugitive Slave Law. Clay’s bill pleased nobody, and was soundly defeated. Illinois Democrat Stephen Douglas separated the individual provisions and scraped together the votes to get each individual measure passed in what has become known as the Compromise of 1850. In reality, the measure represented a truce more than a compromise. The passage of the individual measures, however contentious, satisfied most of the demands of the Nashville Convention and depressed support for secession. Conditional unionist candidates, or candidates who advocated remaining in the Union as long as conditions like those articulated at Nashville were met, did well in elections throughout the South in 1850 and 1852.

Despite the boost that the Compromise of 1850 gave to conditional unionism in the South, two provisions of the Compromise prevented lasting resolution. One was the Fugitive Slave Law. While Article IV of the U.S. Constitution asserted the rights of masters to recapture slaves who fled to free states, the Fugitive Slave Law included new and harsher provisions mandating the participation of northern states and individuals in the recapture process and curtailing the rights of alleged fugitives to prove they were not runaways. The severity of the law and the conflict it created between state and federal jurisdiction led to controversy. Harriet Beecher Stowe published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a novel that gained great popularity in the North but was banned in the South. The New England states, Wisconsin, Ohio, and Michigan passed personal liberty laws allowing state citizens to refrain from participating in slave recaptures if prompted by personal conscience to refrain. Rescue cases like those of Anthony Burns in Massachusetts and Joshua Glover in Wisconsin captured headlines and further strained relations between northern and southern states.

The second problem with the Compromise of 1850 was that it did not settle the question of slavery’s expansion because it rejected the Wilmot Proviso without offering an alternative, an omission whose magnitude became apparent when Kansas Territory opened to white settlement in 1854. Fearing that southern congressmen would impede the opening of Kansas because slavery was barred there by the Missouri Compromise (which prohibited slavery in the Louisiana Purchase above the 36° 30’ latitude), Democratic senator Stephen Douglas of Illinois introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which threw out the Missouri Compromise and opened Kansas and Nebraska Territories to popular sovereignty.

The result was that violence erupted between proslavery and free-state settlers in Kansas. Proslavery advocates from Missouri initially gained the upper hand and, in an election in which 6,318 votes were cast despite the presence of only 2,905 legal voters in Kansas, elected a pro-slavery convention. In 1857 the convention drafted the Lecompton constitution, which would have admitted Kansas to the Union as a slave state and limited the civil rights of antislavery settlers, and sent it to Washington for congressional approval over the objections of the majority of Kansans.

The violence in “Bleeding Kansas” and the obvious unpopularity of the Lecompton constitution did more than just illustrate the failure of popular sovereignty to resolve the slavery extension issue. Kansas further weakened the Second Party System by speeding the collapse of the Whig Party, facilitating the emergence of the Republican Party, and deepening divisions within the Democratic Party. Crippled by its inability to deal effectively with the slavery question, the Whig Party steadily weakened and for a brief time, the anti-immigrant American Party (or Know-Nothings) appeared likely to become the second major party. But when the Know-Nothings failed to respond effectively to the Kansas-Nebraska Act, they lost support among Northerners.

Meanwhile, Free-Soil Democrats, former Whigs, and veterans from the Liberty and Free Soil parties united within several northern states to form a new party explicitly pledged to prevent the westward expansion of slavery. The new party allegedly adopted its name, the Republican Party, at a meeting in Ripon, Wisconsin. Discontented Democrats like Salmon Chase, Charles Sumner, Joshua Giddings, and Gerritt Smith helped to knit the newly emerging state organizations into a sectionwide party by publishing “An Appeal of the Independent Democrats in Congress to the People of the United States” in two newspapers the day after the introduction of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill. The appeal criticized slavery as immoral and contrary to the principles of the nations founders, and it portrayed the question of slavery in Kansas and other territories as a crisis of American democracy because a “slave power conspiracy” was attempting to fasten slavery on the entire nation, even at the cost of suppressing civil liberties and betraying the principles of the American Revolution.

The violence in Kansas seemed to support charges of a slave power conspiracy, especially in May 1856, when pro-slavery settlers sacked the abolitionist town of Lawrence, Kansas—just one day before South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks marched onto the Senate floor to beat Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner into unconsciousness in retaliation for Sumner’s fiery “Crime against Kansas” speech, which portrayed proslavery Southerners generally—and one of Brooks’s relatives particularly—in an unflattering light. “Bleeding Sumner and Bleeding Kansas” made Republican charges that a small number of slaveholders sought to dominate the nation and suppress rights persuasive to many northern voters in the 1856 election; Republican candidate John C. Fremont lost to Democrat James Buchanan, but he carried the New England states, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and New York, and Republican candidates won seats in Congress and state offices in the North.

In 1857, a financial panic, the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott v. Sanford case, and the Lecompton constitution built Republican strength in the North while the Democratic Party fractured. Dred Scott, a slave taken to Illinois and Wisconsin Territory by his master and then brought back to slavery in Missouri, sued for his freedom on the grounds that residency in states and territories where slavery was illegal made him free. Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s decision against Scott declared that blacks could not be citizens, even though several northern states recognized them as such, and that in fact they had “no rights which the white man is bound to respect”; it also held that Congress could not outlaw slavery in any U.S. territory, and that slaveholders retained the right to take slaves wherever they pleased. By denying the right of Congress, territorial governments, or residents of a territory to ban slavery from their midst, Taney’s decision seemed to support Republican charges that southern oligarchs sought to fasten slavery onto the entire nation regardless of local sentiment. When President James Buchanan (a Pennsylvanian thought to be controlled by southern Democrats) tried unsuccessfully to force Congress to ratify the Lecompton constitution and admit Kansas as a slave state over the objections of the majority of Kansans, the Democratic Party splintered. Even Stephen Douglas faced stiff competition for his Senate seat in 1858. In a series of debates throughout Illinois, Douglas faced Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln, who articulated the slave power conspiracy theme and outlined a platform of opposition to the extension of slavery. Because the Democrats retained a slim edge in the state legislature and state legislatures (not the popular vote) selected senators, Douglas retained his Senate seat. But the wide press coverage of the Lincoln-Douglas debates gained a national audience for Lincoln and his views.

The fast but exclusively northern growth of the Republicans alarmed Southerners who saw themselves as potential victims of a “Black Republican” conspiracy to isolate slavery and end it, sentence the South to subservient status within the Union, and destroy it by imposing racial equality. With conditional unionism still dominant throughout much of the South, many southern leaders called for firmer federal support for the Fugitive Slave Law, federal intolerance for state personal liberty laws, and a federal slave code mandating the legality of and federal protection for slavery in all U.S. territories as prerequisites for southern states remaining in the Union. The Fire Eaters added the demand for the reopening of the African slave trade, even as they increasingly insisted that southern states could preserve their rights only by leaving a Union growing more hostile to the institution on which the South depended. Fears of a “Black Republican” conspiracy seemed to be realized in 1859 when John Brown seized the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in hopes of overthrowing slavery by inspiring slave insurrection throughout the South. Brown failed and was executed for treason in December 1859, but a white Northerner marching South to arm slaves embodied white Southerners’ grimmest fears that the growing strength of the Republican Party could only lead to violent insurrections.

The Democratic Party split deepened in 1860, setting the stage for the election of a Republican president. In January 1860, Mississippi senator Albert Brown submitted resolutions calling for a federal slave code and an expanded role for Congress in promoting slavery. The Alabama State Democratic Convention identified the resolutions as the only party platform it would support in the presidential election; several additional southern state delegations also committed themselves to the “Alabama Platform.” Northern Democrats espoused popular sovereignty instead. When the National Democratic Convention assembled in Charleston, South Carolina, it split along sectional lines.

As the Democratic rift widened in 1859–60, the Republican Party faced the decision of how best to capitalize on its opponents’ dissent. Should it nominate a well-known candidate like senator and former New York governor William Seward, who was seen as a radical because of famous speeches declaring that slavery was subject to a “higher law” than the Constitution (1850) and that the slave and free states were locked in an “irreconciliable conflict” (1858)? Or should it nominate a more moderate but lesser-known candidate? After four ballots, the Republican convention in Chicago settled on Abraham Lincoln, a less prominent politician whose debates with Douglas and a February 1860 New York City address about slavery and the founders had helped introduce him to a national audience. The convention also adopted a platform that decried John Brown and advocated economic measures like a homestead act, but its most important plank consisted of its opposition to the expansion of slavery.

The 1860 presidential campaign shaped up differently in the North and South. Southern Democrats nominated John Breckinridge, who ran on the Alabama platform. He vied for southern votes with John Bell of the newly created Constitutional Union Party, a party that appealed to moderate Southerners who saw the Alabama platform as dangerously inflammatory and instead supported the maintenance of slavery where it was but took no stand on its expansion. In the North, Democrat Stephen Douglas and his platform of popular sovereignty opposed Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln and the Republican nonextension platform. No candidate won a majority of the popular vote. Stephen Douglas captured the electoral votes of New Jersey and Missouri. John Bell carried Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. John Breckinridge won every remaining slave state, and Abraham Lincoln, with 54 percent of the northern popular vote (and none of the southern popular vote) took every remaining free state and the election.

Anticipating Lincoln’s victory, the South Carolina legislature stayed in session through the election so that it could call a secession convention as soon as results were known. On December 20, 1860, the convention unanimously approved an ordinance dissolving the union between South Carolina and the United States. By February 1, 1861, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana, and Texas had also seceded in response to the election results. The secession ordinances all made clear that Lincoln’s election on a nonextension of slavery platform and northern failure to uphold the Fugitive Slave Clause entitled southern states to leave the Union. Delegates from the seven states met in Montgomery, Alabama, to form the Confederate States of America, draft a provisional constitution, select Jefferson Davis and Alexander Stephens as provisional president and vice president, and authorize the enrollment of 100,000 troops.

The states of the Upper and Border South, where Constitutional Unionist candidate John Bell had done well, resisted Deep South pressure to secede immediately, and instead waited to see if Lincoln’s actions as president could be reconciled with assurances for slavery’s safety within the Union. Yet they also passed coercion clauses, pledging to side with slaveholding states if the situtation came to blows. Congress considered the Crittenden Compromise, which guaranteed perpetual noninterference with slavery, extended the Missouri Compromise line permanently across the United States, forbade abolition in the District of Columbia without the permission of Maryland and Virginia, barred Congress from meddling with the interstate slave trade, earmarked federal funds to compensate owners of runaway slaves, and added an unamendable amendment to the constitution guaranteeing that none of the Crittenden measures, including perpetual noninterference with slavery, could ever be altered. The Crittenden Compromise failed to soothe conditional unionists in the South while it angered Republican voters in the North by rejecting the platform that had just won the election. Stalemate ensued.

The Fort Sumter Crisis pressured both Lincoln and the states of the Upper South into action. When Lincoln took office in March 1861, all but four federal forts in seceded states had fallen. Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor remained in Union hands but was short of supplies. South Carolina officials warned that any attempt to resupply the fort would be seen as an act of aggression. Believing that he could not relinquish U.S. property to a state in rebellion, nor could he leave U.S. soldiers stationed at Fort Sumter to starve, Lincoln warned Confederate president Davis and South Carolina officials that a ship with provisions but no ammunition would resupply Fort Sumter. In the early morning hours of April 12, 1861, South Carolina forces bombarded Fort Sumter before the supply ship could arrive; Fort Sumter surrendered on April 14. Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to serve for 90 days to put down the rebellion. In response, Virginia, Arkansas, North Carolina, and Tennessee seceded. The border slave states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri remained in the Union, though each state except Delaware contained a significant secessionist minority.

Fought from 1861 to 1865, the Civil War settled the question of slavery’s extension by eventually eliminating slavery. The war also made the growth of federal power possible, although dramatic growth in the federal government would not really occur until the later Progressive and New Deal Eras. Conflicts between state and federal sovereignty would persist in U.S. political history, but the Civil War removed secession as a possible option for resolving those conflicts.

See also Civil War and Reconstruction; Confederacy; Reconstruction Era, 1865–77; slavery.

FURTHER READING

Earle, Jonathan H. Jacksonian Antislavery and the Politics of Free Soil, 1824–1854. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Gienapp, William E. “The Crisis of American Democracy: The Political System and the Coming of the Civil War.” In Why The Civil War Came, edited by Gabor S. Boritt. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996.

___. The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Howe, Daniel Walker. What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815–1848. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Potter, David. The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861. New York: Harper and Row, 1976.

Richards, Leonard L. The California Gold Rush and the Coming of the Civil War. New York: Knopf, 2007.

Rothman, Adam. “The ‘Slave Power’ in the United States, 1783—1865.” In Ruling America: A History of Wealth and Power in a Democracy, edited by Steve Fraser and Gary Gerstle. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Sewell, Richard H. Ballots for Freedom: Antislavery Politics in the United States, 1837–1860. New York: Oxford University Press, 1976.

Stampp, Kenneth M. America in 185J: A Nation on the Brink. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990.

Wilentz, Sean. The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln. New York: Norton, 2005.

CHANDRA MANNING

Jim Crow is the system of racial oppression—political, social, and economic—that southern whites imposed on blacks after the abolition of slavery. Jim Crow, a term derived from a minstrel-show routine, was a derogatory epithet for blacks. Although the system met its formal demise during the civil rights movement of the 1960s, its legacy is still felt today.

During Reconstruction (1865–77), recently enfranchised southern blacks voted in huge numbers and elected many black officeholders. During the final decades of the nineteenth century, however, black voting in the South was largely eliminated—first through fraud and violence, then through legal mechanisms such as poll taxes and literacy tests. Black voter registration in Alabama plummeted from 180,000 in 1900 to 3,000 in 1903 after a state constitutional convention adopted disfranchising measures.

When blacks could not vote, neither could they be elected to office. Sixty-four blacks had sat in the Mississippi legislature in 1873; none sat after 1895. In South Carolina’s lower house, which had a black majority during Reconstruction, a single black remained in 1896. More importantly, after disfranchisement, blacks could no longer be elected to the local offices that exercised control over people’s daily lives, such as sheriff, justice of the peace, and county commissioner.

With black political clout stunted, radical racists swept to power. Cole Blease of South Carolina bragged that he would rather resign as governor and “lead the mob” than use his office to protect a “nigger brute” from lynching. Governor James Vardaman of Mississippi promised that “every Negro in the state w[ould] be lynched” if necessary to maintain white supremacy.

Jim Crow was also a system of economic subordination. After the Civil War ended slavery, most southern blacks remained under the economic control of whites, growing cotton as sharecroppers and tenant farmers.

Laws restricted the access of blacks to nonagricultural employment while constricting the market for agricultural labor, thus limiting the bargaining power of black farmworkers. The cash-poor cotton economy forced laborers to become indebted to landlords and suppliers, and peonage laws threatened criminal liability for those who sought to escape indebtedness by breaching their labor contracts. Once entrapped by the criminal justice system, blacks might be made to labor on chain gangs or be hired out to private employers who controlled their labor in exchange for paying their criminal fines. During planting season, when labor was in great demand, local law enforcement officers who were in cahoots with planters would conduct “vagrancy roundups” or otherwise “manufacture” petty criminals.

Some black peons were held under conditions almost indistinguishable from slavery. They worked under armed guard, were locked up at night, and were routinely beaten and tracked down by dogs if they attempted to escape. Blacks who resisted such conditions were often killed. In one infamous Georgia case in the 1920s, a planter who was worried about a federal investigation into his peonage practices simply ordered the murder of 11 of his tenants who were potential witnesses.

While southern black farmers made gains in land ownership in the early twentieth century, other economic opportunities for blacks contracted. Whites repossessed traditionally black jobs, such as barber and chef. The growing power of racially exclusionary labor unions cut blacks off from most skilled trade positions. Black lawyers increasingly found themselves out of work, as a more rigid color line forbade their presence in some courtrooms and made them liabilities to clients in others. Beginning around 1910, unionized white railway workers went on strike in an effort to have black firemen dismissed; when the strike failed, they simply murdered many of the black workers.

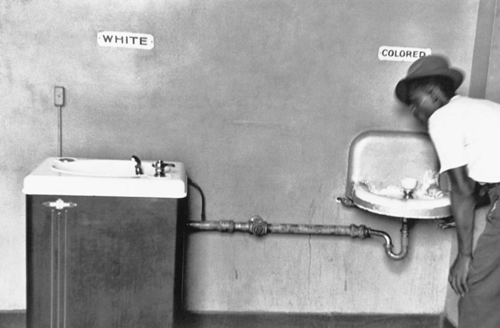

As blacks lost their political clout and white racial attitudes hardened, racial segregation spread into new spheres of southern life. Beginning around 1890, most southern states required railroads to segregate their passengers, and laws segregating local streetcars swept the South soon after 1900. Many southern states also segregated restaurants, theaters, public parks, jails, and saloons. White nurses were forbidden to treat black hospital patients, and white teachers were forbidden to work in black schools. Banks established separate deposit windows for blacks. Beginning in 1910, southern cities adopted the first residential segregation ordinances.

Segregation statutes required that accommodations for blacks be equal, but in practice they never were. Blacks described Jim Crow railway cars as “scarcely fit for a dog to ride in”; the seats were filthy and the air was fetid. Convicts and the insane were relegated to these cars, which white passengers entered at will to smoke, drink, and antagonize blacks. Such conditions plainly violated state law, yet legal challenges were rare.

Notwithstanding state constitutional requirements that racially segregated schools be equal, southern whites moved to dismantle the black education system. Most whites thought that an education spoiled good field hands, needlessly encouraged competition with white workers, and rendered blacks dissatisfied with their subordinate status. In 1901 Georgia’s governor, Allen D. Candler, stated, “God made them negroes and we cannot by education make them white folks.” Racial disparities in educational funding became enormous. By 1925–26, South Carolina spent $80.55 per capita for white students and $10.20 for blacks; for school transportation, the state spent $471,489 for whites and $795 for blacks.

Much social discrimination resulted from informal custom rather than legal rule. No southern statute required that blacks give way to whites on public sidewalks or refer to whites by courtesy titles, yet blacks failing to do so acted at their peril. In Mississippi, some white post office employees erased the courtesy titles on mail addressed to black people.

Jim Crow was ultimately secured by physical violence. In 1898 whites in Wilmington, North Carolina, concluded a political campaign fought under the banner of white supremacy by murdering roughly a dozen blacks and driving 1,400 out of the city. In 1919, when black sharecroppers in Phillips County, Arkansas, tried to organize a union and challenge peonage practices, whites responded by murdering dozens of them. In Orange County, Florida, 30 blacks were burned to death in 1920 because 1 black man had attempted to vote.

Thousands of blacks were lynched during the Jim Crow era. Some lynching victims were accused of nothing more serious than breaches of racial etiquette, such as “general uppityness.” Prior to 1920, efforts to prosecute even known lynchers were rare and convictions virtually nonexistent. Public lynchings attended by throngs of people, many of whom brought picnic lunches and took home souvenirs from the victims tortured body, were not uncommon.

Jim Crow was a southern phenomenon, but its persistence required national complicity. During Reconstruction, the national government had—sporadically—used force to protect the rights of southern blacks. Several factors account for the gradual willingness of white Northerners to permit white Southerners a free hand in ordering southern race relations.

Black migration to the North, which more than doubled in the decades after 1890 before exploding during World War I, exacerbated the racial prejudices of northern whites. As a result, public schools and public accommodations became more segregated, and deadly white-on-black violence erupted in several northern localities. Around the same time, the immigration of millions of southern and eastern European peasants caused native-born whites to worry about the dilution of “Anglo-Saxon racial stock,” rendering them more sympathetic to southern racial policies. The resurgence of American imperialism in the 1890s also fostered the convergence of northern and southern racial attitudes, as imperialists who rejected full citizenship rights for residents of the new territories were not inclined to protest the disfranchisement of southern blacks.

Such developments rendered the national government sympathetic toward southern Jim Crow. Around 1900, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected constitutional challenges to racial segregation and black disfranchisement, made race discrimination in jury selection nearly impossible to prove, and sustained the constitutionality of separate-and-unequal education for blacks. Meanwhile, Congress repealed most of the voting rights legislation enacted during Reconstruction and declined to enforce Section II of the Fourteenth Amendment, which requires reducing the congressional representation of any state that disfranchises adult male citizens for reasons other than crime.

Presidents proved no more inclined to challenge Jim Crow. William McKinley who was born into an abolitionist family and served as a Union officer during the Civil War, ignored the imprecations of black leaders to condemn the Wilmington racial massacre of 1898, and his presidential speeches celebrated sectional reconciliation, which was accomplished by sacrificing the rights of southern blacks. His successor, Theodore Roosevelt, refused to criticize black disfranchisement, blamed lynchings primarily on black rapists, and proclaimed that “race purity must be maintained.” Roosevelt’s successor, William Howard Taft, endorsed the efforts of southern states to avoid domination by an “ignorant, irresponsible electorate,” largely ceased appointing blacks to southern patronage positions, and denied that the federal government had the power or inclination to interfere in southern race relations.

A variety of forces contributed to the gradual demise of Jim Crow. Between 1910 and 1960, roughly 5 million southern blacks migrated to the North, mainly in search of better economic opportunities. Because northern blacks faced no significant suffrage restrictions, their political power quickly grew. At the local level, northern blacks secured the appointment of black police officers, the creation of playgrounds and parks for black neighborhoods, and the election of black city council members and state legislators. Soon thereafter, northern blacks began influencing national politics, successfully pressuring the House of Representatives to pass an antilynching bill in 1922 and the Senate to defeat the Supreme Court nomination of a southern white supremacist in 1930.

The rising economic status of northern blacks facilitated social protest. Larger black populations in northern cities provided a broader economic base for black entrepreneurs and professionals, who would later supply resources and leadership for civil rights protests. Improved economic status also enabled blacks to use boycotts as levers for social change. The more flexible racial mores of the North permitted challenges to the status quo that would not have been tolerated in the South. Protest organizations, such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and militant black newspapers, such as the Chicago Defender, developed and thrived in the North. Because of a less rigid caste structure, blacks in the North were less likely to internalize racist norms of black subordination and inferiority.

Jim Crow was also being gradually eroded from within. Blacks moved from farms to cities within the South in search of better economic opportunities, eventually fostering a black middle class, which capitalized on the segregated economy to develop sufficient wealth and leisure time to participate in social protest. Many blacks in the urban South were economically independent of whites and thus could challenge the racial status quo without endangering their livelihoods. In cities, blacks found better schools, freer access to the ballot box, and a more relaxed code of racial etiquette. Because urban blacks enjoyed better communication and transportation facilities and shared social networks through black colleges and churches, they found it somewhat easier to overcome the organizational obstacles confronting any social protest movement.

World Wars I and II had profound implications for Jim Crow. Wars fought “to make the world safe for democracy” and to crush Nazi fascism had ideological implications for racial equality. In 1919, W.E.B. Du Bois of the NAACP wrote: “Make way for Democracy! We saved it in France, and by the Great Jehovah, we will save it in the United States of America, or know the reason why.” Blacks who had borne arms for their country and faced death on the battlefield were inspired to assert their rights. A black journalist noted during World War I, “The men who did not fear the trained veterans of Germany will hardly run from the lawless Ku Klux Klan.” Thousands of black veterans tried to register to vote after World War II, many expressing the view of one such veteran that “after having been overseas fighting for democracy, I thought that when we got back here we should enjoy a little of it.”

World War II exposed millions of Southerners, white and black, to more liberal racial attitudes and practices. The growth of the mass media exposed millions more to outside influence, which tended to erode traditional racial mores. Media expansion also prevented white Southerners from restricting outside scrutiny of their treatment of blacks. Northerners had not seen southern lynchings on television, but the brutalization of peaceful black demonstrators by southern white law enforcement officers in the 1960s came directly into their living rooms.

Formal Jim Crow met its demise in the 1960s. Federal courts invalidated racial segregation and black disfranchisement, and the Justice Department investigated and occasionally prosecuted civil rights violations. Southern blacks challenged the system from within, participating in such direct-action protests as sit-ins and freedom rides. Brutal suppression of those demonstrations outraged northern opinion, leading to the enactment of landmark civil rights legislation, which spelled the doom of formal Jim Crow.

Segregated water fountains, North Carolina, 1950. (Elliott Erwitt/Magnum Photos)

Today, racially motivated lynchings and state-sponsored racial segregation have largely been eliminated. Public accommodations and places of employment have been integrated to a significant degree. Blacks register to vote in roughly the same percentages as whites, and more than 9,000 blacks hold elected office. The previous two secretaries of state have been black.

Blacks have also made dramatic gains in education and employment. The difference in the median number of school years completed by blacks and whites, which was 3.5 in 1954, has been eliminated almost entirely. The number of blacks holding white-collar or middle-class jobs increased from 12.1 percent in 1960 to 30.4 percent in 1990. Today, black men with college degrees earn nearly the same income as their white counterparts.

Yet not all blacks have been equally fortunate. In 1990 nearly two-thirds of black children were born outside of marriage, compared with just 15 percent of white children. Well over half of black families were headed by single mothers. The average black family has income that is just 60 percent and wealth that is just 10 percent of those of the average white family. Nearly 25 percent of blacks—three times the percentage of whites—live in poverty. Increasing numbers of blacks live in neighborhoods of extreme poverty, which are characterized by dilapidated housing, poor schools, broken families, juvenile pregnancies, drug dependency, and high crime rates.

Residential segregation compounds the problems of the black urban underclass. Spatial segregation means social isolation, as most inner-city blacks are rarely exposed to whites or the broader culture. As a result, black youngsters have developed a separate dialect of sorts, which disadvantages them in school and in the search for employment. Even worse, social segregation has fostered an oppositional culture among many black youngsters that discourages academic achievement—“acting white”—and thus further disables them from succeeding in mainstream society.

Today, more black men are incarcerated than are enrolled in college. Blacks comprise less than 12 percent of the nation’s population but more than 50 percent of its prison inmates. Black men are seven times more likely to be incarcerated than white men. The legacy of Jim Crow lives on.

See also African Americans and politics; South since 1877; voting.

FURTHER READING

Ayers, Edward L. Promise of the New South: Life after Reconstruction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Dittmer, John. Black Georgia in the Progressive Era 1900–1920. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1977.

Fairclough, Adam. Better Day Coming: Blacks and Equality, 1890–2000. New York: Viking Penguin, 2001.

Gilmore, Glenda Elizabeth. Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896–1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Klarman, Michael J. From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Litwack, Leon. Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow. New York: Vintage Books, 1998.

McMillen, Neil R. Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

Myrdal, Gunnar. An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. 2 vols. New York: Harper and Bros., 1944.

Woodward, C. Vann. The Strange Career of Jim Crow. 3rd revised ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974.

Wright, George C. Life behind a Veil: Blacks in Louisville, Kentucky 1865–1920. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990.

MICHAEL J. KLARMAN

The framers of the U.S. Constitution viewed the Senate as a check on the more passionate whims of the House of Representatives. Known as the “greatest deliberative body,” the Senate has traditionally valued procedure over expediency, thereby frustrating action-oriented House members and presidents. Despite its staid reputation, however, the Senate has produced many of American history’s most stirring speeches and influential policy makers. Indeed, the upper chamber of Congress has both reflected and instigated changes that have transformed the United States from a small, agrarian-based country to a world power.

In its formative years, the Senate focused on foreign policy and establishing precedents on treaty, nomination, and impeachment proceedings. Prior to the Civil War, “golden era” senators attempted to keep the Union intact while they defended their own political ideologies. The Senate moved to its current chamber in 1859, where visitors soon witnessed fervent Reconstruction debates and the first presidential impeachment trial. Twentieth-century senators battled the executive branch over government reform, international relations, civil rights, and economic programs as they led investigations into presidential administrations. While the modern Senate seems steeped in political rancor, welcome developments include a more diverse membership and bipartisan efforts to improve national security.

Drafted during the 1787 Constitutional Convention, the Constitution’s Senate-related measures followed precedents established by colonial and state legislatures, as well as Great Britain’s parliamentary system. The delegates to the convention, however, originated the institution’s most controversial clause: “The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, chosen by the Legislature thereof….” Although delegates from large states supported James Madison’s Virginia Plan, which based Senate representation on state population, small-state delegates wanted equal representation in both the House and the Senate. Roger Sherman sought a third option: proportional representation in the House and equal representation in the Senate. Adopted by the delegates on July 16, Sherman’s Connecticut Compromise enabled the formation of a federal, bicameral legislature responsive to the needs of citizens from both large and small states.

Compared to the representation issue, the measure granting state legislatures the right to choose senators proved less divisive to convention delegates. Madison dismissed concerns that indirect elections would lead to a “tyrannical aristocracy,” and only James Wilson argued that senators chosen in this manner would be swayed by local interests and prejudices. By the late nineteenth century, however, corruption regarding the selection of senators triggered demands for electoral reform. Ratified in 1913, the Seventeenth Amendment established direct election, allowing individual voters to select their senators.

As outlined in Article I of the Constitution, the Senate’s primary role is to pass bills in concurrence with the House of Representatives. In the event that a civil officer committed “high crimes and misdemeanors,” the Constitution also gives the Senate the responsibility to try cases of impeachment brought forth by the House. And, under the Constitution’s advice and consent clause, the upper chamber received the power to confirm or deny presidential nominations, including appointments to the cabinet and the federal courts, and the power to approve or reject treaties. The Senate’s penchant for stalling nominations and treaties in committee, though, has defeated more executive actions than straight up-or-down votes.

Within a year after the Constitutional Convention concluded, the central government began its transition from a loose confederation to a federal system. In September 1788, Pennsylvania became the first state to elect senators: William Maclay and Robert Morris. Other legislatures soon followed Pennsylvania’s lead, selecting senators who came, in general, from the nations wealthiest and most prominent families.

The first session of Congress opened in the spring of 1789 in New York City’s Federal Hall. After meeting its quorum in April, the Senate originated one of the most important bills of the era: the Judiciary Act of 1789. Created under the direction of Senator Oliver Ellsworth, the legislation provided the structure of the Supreme Court, as well as the federal district and circuit courts. Although advocates of a strong, federal judiciary system prevailed, the bill’s outspoken critics indicated the beginning of the states’ rights movement in the Senate, a source of significant division in the nineteenth century.

Between 1790 and 1800, Congress sat in Philadelphia as the permanent Capitol underwent construction in Washington, D.C. During these years, the first political parties emerged: the Federalists, who favored a strong union of states, and the anti-Federalists, later known as Republicans, who were sympathetic to states’ rights. The parties aired their disputes on the Senate floor, especially in debates about the controversial Jay Treaty (1794) and the Alien and Sedition Acts (1798).

Negotiated by Chief Justice John Jay, the Jay Treaty sought to resolve financial and territorial conflicts with Great Britain arising from the Revolutionary War. In the Senate, the pro-British Federalists viewed the treaty as a mechanism to prevent another war, while the Republicans, and much of the public, considered the treaty’s provisions humiliating and unfair to American merchants. By an exact two-thirds majority, the treaty won Senate approval, inciting anti-Jay mobs to burn and hang senators in effigy.

Partisan battles erupted again in 1798, when the Federalist-controlled Congress passed four bills known as the Alien and Sedition Acts. Meant to curtail Republican popularity, the legislation, in defiance of the First Amendment, made it unlawful to criticize the government. Ironically, the acts unified the Republican Party, leading to Thomas Jefferson’s presidential election and a quarter-century rule by Senate Republicans.

The Federalist-Republican power struggle continued in the new Capitol in Washington. In 1804 the Senate, meeting as a court of impeachment, found the Federalist U.S. district court judge John Pickering guilty of drunkenness and profanity and removed him from the bench. The following year, the Senate tried the Federalist Supreme Court justice Samuel Chase for allegedly exhibiting an anti-Republican bias. Chase avoided a guilty verdict by one vote, which restricted further efforts to control the judiciary through the threat of impeachment.

Prior to the War of 1812, foreign policy dominated the Senate agenda. Responding to British interference in American shipping, the Senate passed several trade embargoes against Great Britain before declaring war. In 1814 British troops entered Washington and set fire to the Capitol, the White House, and other public buildings. The Senate chamber was destroyed, forcing senators to meet in temporary accommodations until 1819. In the intervening years, the Senate formed its first permanent committees, which encouraged senators to become experts on such issues as national defense and finance.

When the war concluded in 1815 without a clear victor, the Senate turned its attention to the problems and opportunities resulting from territorial expansion. As lands acquired from France, Spain, and Indian tribes were organized into territories and states, senators debated the future of slavery in America, the nation’s most divisive issue for years to come.

In 1820 the 46 senators were split evenly between slave states and free states. The Senate considered numerous bills designed to either protect or destroy this delicate balance. Legislation regulating statehood produced the Missouri Compromise (1820–21), the Compromise of 1850, and the Kansas-Nebraska Act (1854). While the compromises attempted to sustain the Union, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, with its controversial “popular sovereignty” clause, escalated the conflict between slave owners and abolitionists.

Senate historians consider the antebellum period to be the institution’s golden era. The Senate chamber, a vaulted room on the Capitol’s second floor, hosted passionate floor speeches enthralling both the public and the press. At the center of debate stood the Senate’s “Great Triumvirate”: Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun.

As Speaker of the House, Clay had overseen the formation of the Missouri Compromise, which stipulated that Missouri would have no slavery restrictions, while all territories to the north would become free states. Later, as senator, Clay led the opposition against President Andrew Jackson’s emerging Democratic Party. In 1834 he sponsored a resolution condemning Jackson for refusing to provide a document to Congress. Although the first (and only) presidential censure was expunged in 1837, it sparked the rise of the Whig Party in the late 1830s.

Webster, one of the greatest American orators, defended the importance of national power over regional self-interest, declaring in a rousing 1830 speech, “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!” His views challenged Vice President Calhoun’s theory of nullification, which proposed that states could disregard laws they found unconstitutional. By the time Calhoun became a senator in 1832, the Senate had divided between those who promoted states’ rights and those with a nationalist view.

The Mexican-American War inflamed the issue of slavery. Led by Calhoun, the Senate blocked adoption of the House-sponsored Wilmot Proviso (1846) that would have banned slavery in the territories won from Mexico. Fearing a national crisis, Clay drafted new slavery regulations. When Calhoun, now gravely ill, threatened to block any restrictions, Webster responded with a famous address upholding the Missouri Compromise and the integrity of the Union.

After Calhoun’s death in March 1850, the atmosphere in the Senate chamber grew so tense that Henry S. Foote drew a pistol during an argument with antislavery senator Thomas Hart Benton. After months of such heated debates, however, Congress passed Clay’s legislation. As negotiated by Senator Stephen A. Douglas, the Compromise of 1850 admitted California as a free state, allowed New Mexico and Utah to determine their own slavery policies (later known as popular sovereignty), outlawed the slave trade in Washington, D.C., and strengthened the controversial fugitive slave law.

Webster and Clay died in 1852, leaving Douglas, as chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, to manage statehood legislation. Catering to southern senators, Douglas proposed a bill creating two territories under popular sovereignty: Nebraska, which was expected to become a free state, and Kansas, whose future was uncertain. Despite the staunch opposition of abolitionists, the bill became law, prompting pro- and antislavery advocates to flood into “Bleeding Kansas,” where more than 50 settlers died in the resulting conflicts.

Opponents of the Kansas-Nebraska Act formed the modern Republican Party, drawing its membership from abolitionist Whigs, Democrats, and Senator Charles Sumner’s Free Soil Party. In 1856 Sumner gave a scathing “crime against Kansas” speech that referred to slavery as the wicked mistress of South Carolina senator Andrew P. Butler. Three days after the speech, Butler’s relative, Representative Preston S. Brooks, took revenge in the Senate chamber. Without warning, he battered Sumner’s head with blows from his gold-tipped cane. The incident made Brooks a hero of the South, while Sumner, who slowly recovered his health, would become a leader of the Radical Republicans.

In the late 1850s, to accommodate the growing membership of Congress, the Capitol doubled in size with the addition of two wings. The new Senate chamber featured an iron and glass ceiling, multiple galleries, and a spacious floor. It was in this setting that conflicts with the Republican-majority House led to legislative gridlock, blocking a series of Senate resolutions meant to appease the South. In December 1860, South Carolina announced its withdrawal from the Union. One month later, in one of the Senate’s most dramatic moments, the Confederacy’s future president, Jefferson Davis, and four other southern senators resigned their seats, foretelling the resignation of every senator from a seceding state except Andrew Johnson, who remained until 1862.

Following the fall of Fort Sumter in April 1861, Washington, D.C., was poised to become a battle zone. A Massachusetts regiment briefly occupied the Senate wing, transforming it into a military hospital, kitchen, and sleeping quarters. Eventually, thousands of troops passed through the chamber and adjacent rooms. One soldier gouged Davis’s desk with a bayonet, while others stained the ornate carpets with bacon grease and tobacco residue.

Now outnumbering the remaining Democrats, congressional Republicans accused southern lawmakers of committing treason. For the first time since Senator William Blount was dismissed for conspiracy in 1797, Senate expulsion resolutions received the required two-thirds vote. In total, the Senate expelled 14 senators from the South, Missouri, and Indiana for swearing allegiance to the Confederacy.

Within the Republican majority, the Senate’s Radical Republican contingent grew more powerful during the war. Staunch abolitionists formed the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War to protest President Abraham Lincoln’s management of the army. Radicals demanded an end to slavery and investigated allegations of government corruption and inefficiency. They also passed significant domestic policy laws, such as the Homestead Act (1862) and the Land Grant College Act (1862).

When a northern victory seemed imminent, Lincoln and the congressional Republicans developed different plans for reconstructing the Union. In December 1863, the president declared that states would be readmitted when 10 percent of their previously qualified voters took a loyalty oath. Radicals countered with the Wade-Davis Bill requiring states to administer a harsher, 50 percent oath. Lincoln vetoed the legislation, outraging Senator Benjamin R. Wade and Representative Henry W. Davis.

In the closing days of the war, the Senate passed the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery. After Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, the new president, former senator Andrew Johnson, infuriated congressional Republicans when he enabled Confederate politicians to return to power and vetoed a bill expanding the Freedmen’s Bureau, which assisted former slaves. Republicans, in turn, enacted the Fourteenth Amendment, providing blacks with citizenship, due process of law, and equal protection by laws.

Chaired by Senator William P. Fessenden, the Joint Committee on Reconstruction declared that the restoration of states was a legislative, not an executive, function. Accordingly, Congress passed the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, which divided the South into military districts, permitted black suffrage, and made the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment a condition of state readmittance. To protect pro-Radical civil officials, Republicans proposed the Tenure of Office Act, requiring Senate approval before the president could dismiss a cabinet member.

Johnson violated the act by firing Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, and the House of Representatives impeached him on February 24, 1868. A week later, the Senate convened as a court of impeachment, and on May 16, 35 senators voted to convict Johnson, 1 vote short of the two-thirds majority needed for removal. The case centered on executive rights and the constitutional separation of powers, with 7 moderate Republicans joining the 12 Democrats in voting to acquit.

While Johnson retained his office, he was soon replaced by Ulysses S. Grant, the Civil War general. Marked by corruption, the Grant years (1869–77) split the congressional Republicans into pro- and antiadministration wings. The party was weakened further when representatives and senators were caught accepting bribes to assist the bankrupt Union Pacific Railroad. And after two senators apparently bought their seats from the Kansas legislature, much of the press began calling for popular Senate elections to replace the indirect election method outlined by the Constitution.

Meanwhile, Republicans still dominated southern state legislatures, as most Democrats were unable to vote under Radical Reconstruction. In 1870 Mississippi’s Republican legislature elected the first black U.S. senator, Hiram R. Revels, to serve the last year of an unexpired term. Another black Mississippian, Blanche K. Bruce, served from 1875 to 1881. (Elected in 1966, Edward W. Brooke was the first African American to enter the Senate after Reconstruction.)

The 1876 presidential election ended Radical Reconstruction. Although the Democrat, Samuel J. Tilden, won the popular vote, ballots from Florida, Louisiana, and South Carolina were in dispute. To avert a constitutional crisis, Congress formed an electoral commission composed of five senators, five representatives, and five Supreme Court justices, who chose Republican Rutherford B. Hayes by a one-vote margin. As part of the Compromise of 1877, Republicans agreed to end military rule in the South in exchange for Democratic support of the Hayes presidency.

During the late nineteenth century, corruption permeated the public and private sectors. While the two major parties traded control of the Senate, the Republicans divided between those who wanted institutional reform and those in favor of retaining political patronage, the practice of dispensing government jobs in order to reward or secure campaign support.

New York senator Roscoe Conkling epitomized the problem of patronage. In the 1870s, he filled the New York Custom House with crooked friends and financial backers. Moderates from both parties called for a new method to select government workers. In 1881 a disturbed patronage seeker assassinated President James A. Garfield. The act motivated Democratic senator George H. Pendleton to sponsor legislation creating the merit-based civil service category of federal jobs.

In 1901 William McKinley’s assassination elevated progressive Republican Theodore Roosevelt to the White House, while Republicans once again dominated the Senate. As chairman of the Republican Steering Committee, as well as the Appropriations Committee, William B. Allison dominated the chamber along with other committee chairmen. In a showdown between two factions of Republicans, Allison’s conservative Old Guard blocked progressives’ efforts to revise tariffs. Despite the continued opposition of conservatives, however, Roosevelt achieved his goal of regulating railroad rates and large companies by enforcing Senator John Sherman’s Antitrust Act of 1890.

Prior to World War I, Progressive Era reformers attempted to eradicate government corruption and increase the political influence of the middle class. The campaign for popular Senate elections hoped to achieve both goals. In 1906 David Graham Phillips wrote several muckraking magazine articles exposing fraudulent relationships between senators, state legislators, and businessmen. His “Treason of the Senate” series sparked new interest in enabling voters, rather than state legislatures, to elect senators. But although the Seventeenth Amendment (1913) standardized direct elections, the institution remained a forum for wealthy elites.

In 1913 reform-minded Democrats took over the Senate, as well as the presidency under Woodrow Wilson, resulting in a flurry of progressive legislation. Wilson’s Senate allies, John Worth Kern and James Hamilton Lewis, ushered through the Federal Reserve Act (1913), the Federal Trade Commission Act (1914), and the Clayton Antitrust Act (1914). As chairman of the Democratic Conference, Kern acted as majority leader several years before the position was officially recognized, while Lewis served as the Senate’s first party whip. As such, he counted votes and enforced attendance prior to the consideration of important bills.

Following Europe’s descent into war in 1914, domestic concerns gave way to foreign policy, and Wilson battled both progressive and conservative Republicans in Congress. On January 22, 1917, Wilson addressed the Senate with his famous “peace without victory” speech. Shortly thereafter, a German submarine sank an unarmed U.S. merchant ship, and the president urged Congress to pass legislation allowing trade vessels to carry weapons. Non-interventionist senators, including progressive Republicans Robert M. La Follette and George W. Norris, staged a lengthy filibuster in opposition to Wilson’s bill, preventing its passage. Furious, Wilson declared that a “little group of willful men” had rendered the government “helpless and contemptible.” Calling a special Senate session, he prompted the passage of Rule 22, known as the cloture rule, which limited debate when two-thirds (later changed to three-fifths) of the senators present agreed to end a filibuster.

The 1918 elections brought Republican majorities to both houses of Congress. As the Senate’s senior Republican, Massachusetts senator Henry Cabot Lodge chaired the Foreign Relations Committee and his party’s conference. Angered by the lack of senators at the Paris Peace Conference (1919), the de facto floor leader attached 14 reservations to the war-ending Treaty of Versailles, altering the legal effect of selected terms, including the provision outlining Wilson’s League of Nations (the precursor to the United Nations), which Lodge opposed. The Senate split into three groups: reservationists, irreconcilables, and pro-treaty Democrats, who were instructed by Wilson not to accept changes to the document. Unable to reach a compromise, the Senate rejected the treaty in two separate votes. Consequently, the United States never entered the League of Nations and had little influence over the enactment of the peace treaty.

In the 1920s, the Republicans controlled both the White House and Congress. Fearing the rising numbers of eastern Europeans and East Asians in America, congressional isolationists curtailed immigration with the National Origins Act of 1924. Senators investigated corruption within the Harding administration, sparking the famous Teapot Dome oil scandal.

Two years after the Nineteenth Amendment gave women the right to vote, Rebecca Latimer Felton, an 87-year-old former suffragist, served as the first woman senator for just 24 hours between November 21 and 22, 1922. Felton considered the symbolic appointment proof that women could now obtain any office. The second female senator, Hattie Wyatt Caraway, was appointed to fill Thaddeus Caraway’s seat upon his death in 1931. She became the first elected female senator, however, when she won the special election to finish her husband’s term in 1932. Caraway won two additional elections and spent more than 13 years in the Senate.

In 1925 the Republicans elected Charles Curtis as the first official majority leader, a political position that evolved from the leadership duties of committee and conference chairmen. Curtis had the added distinction of being the first known Native American member of Congress (he was part Kaw Indian) and was later Herbert Hoover’s vice president.

The 1929 stock market crash signaled the onset of the Great Depression and the end of Republican rule. Democrats swept the elections of 1932, taking back Congress and the White House under Franklin Roosevelt, who promised a “new deal” to address the nations economic woes. The first Democratic majority leader, Joseph T. Robinson, ushered through the presidents emergency relief program, while other senators crafted legislation producing the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Social Security Administration, and the National Labor Relations Board.

In 1937 the Senate majority leader worked furiously to enlist support for Roosevelt’s controversial Court reorganization act, designed to expand the Supreme Court’s membership with liberal justices. Prior to the Senate vote, though, Robinson succumbed to a heart attack, and the president’s “Court-packing” plan died with him. The debate over the bill drove a deep wedge between liberal and conservative Democrats.

In the late 1930s, another war loomed in Europe. Led by Republican senators William E. Borah and Gerald P. Nye, Congress passed four Neutrality Acts. After Germany invaded France in 1940, however, Roosevelt’s handpicked Senate majority leader, Alben W. Barkley, sponsored the Lend-Lease Act (1941), enabling the United States to send Great Britain and its allies billions of dollars in military equipment, food, and services. The monumental aid plan invigorated the economy, ending the Depression, as well as American neutrality.

During the war, little-known senator Harry Truman headed the Senate’s Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program. Elected as Roosevelt’s third vice president in 1944, Truman assumed the presidency when Roosevelt died three months into his fourth term. The new president relied heavily on Senate support as he steered the nation through the conclusion of World War II and into the cold war.

The Senate assumed a primary role in shaping the mid-century’s social and economic culture. In 1944 Senator Ernest W. McFarland sponsored the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act. Better known as the GI Bill, the legislation provided veterans with tuition assistance and low-cost loans for homes and businesses. In 1947 the Republicans regained Congress and passed the antilabor Taft-Hartley Act (1947) over Truman’s veto. The act restricted the power of unions to organize and made conservative senator Robert A. Taft a national figure. Responding to the Soviet Union’s increasing power, the Foreign Relations Committee approved the Truman Doctrine (1947) and the Marshall Plan (1948), which sent billion of dollars of aid and materials to war-torn countries vulnerable to communism.

The Senate itself was transformed by the Legislative Reorganization Act (1946), which streamlined the committee system, increased the number of professional staff, and opened committee sessions to the public. In 1947 television began broadcasting selected Senate hearings. Young, ambitious senators capitalized on the new medium, including C. Estes Kefauver, who led televised hearings on organized crime, and junior senator Joseph R. McCarthy from Wisconsin, whose name became synonymous with the anti-Communist crusade.

In February 1950 Republican senator McCarthy made his first charges against Communists working within the federal government. After announcing an “all-out battle between communistic atheism and Christianity,” he gave an eight-hour Senate speech outlining “81 loyalty risks.” Democrats examined McCarthy’s evidence and concluded that he had committed a “fraud and a hoax” on the public. Meanwhile, Republican senator Margaret Chase Smith, the first woman to serve in both houses of Congress, gave a daring speech, entitled “A Declaration of Conscience,” in which she decried the Senate’s decline into “a forum of hate and character assassination.”

Nevertheless, McCarthy continued to make charges against government officials, and as chairman of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, he initiated more than 500 inquiries and investigations into suspicious behavior, destroying numerous careers along the way. In 1954 McCarthy charged security breaches within the military. During the televised Army-McCarthy hearings, the army’s head attorney, Joseph N. Welch, uttered the famous line that helped bring about the senator’s downfall: “Have you no sense of decency?” On December 2, 1954, senators passed a censure resolution condemning McCarthy’s conduct, thus ending one of the Senate’s darker chapters.

A new era in Senate history commenced in 1955, when the Democrats, now holding a slight majority, elected Lyndon B. Johnson, a former congressman from Texas, to be majority leader. Johnson reformed the committee membership system but was better known for applying the “Johnson technique,” a personalized form of intimidation used to sway reluctant senators to vote his way. The method proved so effective that he managed to get a 1957 civil rights bill passed despite Senator Strom Thurmond’s record-breaking filibuster, lasting 24 hours and 18 minutes. In the 1958 elections, the Senate Democrats picked up an impressive 17 seats. Johnson leveraged the 62–34 ratio to challenge President Dwight D. Eisenhower at every turn, altering the legislative-executive balance of power.

Johnson sought the presidency for himself in 1960 but settled for the vice presidency under former senator John F. Kennedy. Although popular with his colleagues, the new majority leader, Mike Mansfield, faced difficulties uniting liberal and conservative Democrats, and bills affecting minority groups stalled at the committee level. Following Kennedy’s assassination in November 1963, Democrat Hubert H. Humphrey and Republican Everett M. Dirksen engineered the passage of Johnson’s Civil Rights Act of 1964. They did so by first securing a historic cloture vote that halted a filibuster led by southern Democrats Robert C. Byrd and Richard B. Russell. Johnson and Mansfield then won additional domestic policy victories, including the Voting Rights Act (1965) and the Medicare/Medicaid health care programs (1965).

The president’s foreign policy decisions, however, would come to haunt him and the 88 senators who voted for the 1964 Tonkin Gulf Resolution. Drafted by the Johnson administration, the measure drew the nation into war by authorizing the president to take any military action necessary to protect the United States and its allies in Southeast Asia. As the Vietnam War escalated, Senator John Sherman Cooper and Senator Frank F. Church led efforts to reassert the constitutional power of Congress to declare war, culminating in the War Powers Resolution of 1973, which required congressional approval for prolonged military engagements.

Although the Democrats lost the presidency to Richard M. Nixon in 1968, they controlled the Senate until 1981. In 1973 the Senate Select Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities investigated Nixon’s involvement in the cover-up of the 1972 break-in at the Democratic Party’s National Committee office in the Watergate complex. Chaired by Senator Samuel J. Ervin, the select committee’s findings led to the initiation of impeachment proceedings in the House of Representatives. In early August 1974, prominent Republicans, including Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott, Senator Barry Goldwater, and House Minority Leader John Rhodes, informed Nixon that he did not have the party support in either house of Congress to remain in office. Rather than face a trial in the Senate, Nixon resigned prior to an impeachment vote in the House.

From 1981 to 1987, the Republicans controlled the Senate and supported White House policy under President Ronald Reagan. During this period, the Senate began televising floor debates. Televised hearings, however, continued to captivate followers of politics, especially after the Democrats regained the Senate in 1987 and conducted hearings on the Reagan and George H. W. Bush administrations.