This reader is aimed at students of Dutch who are at the high intermediate or early advanced level. Its primary target are class-based students who study Dutch in a foreign language context in university, college or course environments such as evening classes, but the reader can also be used by self-study learners. Students can either pick and mix a selection of chapters from this reader, or work their way through the whole book. A good intermediate command of the language will be necessary from the start. The required starting level is roughly equivalent to the upper intermediate (B2) level of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. This translates approximately to university students who are in the 4th or 5th semesters of their study. Later texts progress into the advanced (C1) level.

There are twelve chapters of readings that are carefully graded. Each reading is accompanied by an extensive vocabulary list. They are followed by reading comprehension questions, vocabulary training, speaking exercises that relate to the topics of the texts and the vocabulary introduced, and Internet research tasks that aim to reinforce the acquired knowledge and skills. Each chapter ends with a short list of suggested further reading.

At the back of the book, students can access a model answer key. There is also a full glossary of all words (Appendix 1), an overview of fixed word combinations (Appendix 2) and a list of irregular verbs (Appendix 3). Appendices 1, 2 and 3 are available as free downloads on the Routledge website at http://www.routledge.com/books/details/9780415550086/.

Approach

This book is emphatically not a complete language method, but a reader. All exercises are designed to support the development of reading skills and of vocabulary in particular. They are designed with constructionist learning theories in mind.

Our emphasis on vocabulary learning is supported by the findings of current research. These show that reading proficiency is largely determined by the extent of a learner’s vocabulary. They also indicate that extensive reading helps to increase a learner’s vocabulary via a process of so-called ‘incidental vocabulary learning’. Attractive texts that are sensibly attuned to the level of the learner will therefore facilitate incidental vocabulary learning and increase the learner’s reading proficiency. However, readers will not always notice new words if they are presented in a (con)text, nor will they always be able to guess the meaning of new words. Furthermore, new words will only take root after considerable, continuously repeated exposure that allows learners to construct new mental models of meaning that are incorporated into pre-existing networks of meaning. In this reader we aim to reinforce this incidental vocabulary learning with ‘intentional vocabulary learning’, and to facilitate the construction of new mental models of meaning and their incorporation into pre-existing networks of meaning through carefully designed exercises and repeated exposure throughout each chapter individually and throughout the reader as a whole.1

This is done in a number of ways. New words are underlined in the text. Their meaning is given in vocabulary lists, which include sample sentences that present yet another context in which the word or word combination could occur. The vocabulary exercises (section 3) present a further opportunity for the learner to actively work with the new words and start incorporating them in a mental network of meaning. The speaking exercises that follow (section 4) are designed to offer learners new opportunities to actively use the vocabulary at hand in communicative situations. Finally, Internet-based tasks (sections 5 and 6) seek to encourage students to explore other relevant resources with the aim of further consolidating their newly acquired knowledge and skills, and engaging in further ‘incidental vocabulary learning’.

Grammar explanations, grammar exercises and writing exercises are not part of the strategy of this reader. If necessary, the tutor can use a selection of our Internet-based tasks as writing assignments. Suggestions are given below.

Chapter structure

The constituent parts of each chapter are:

Introduction (vooraf)

The introduction to each chapter aims to mobilise previous knowledge that students may already have on the topic and its related vocabulary. This will increase understanding of the text, and facilitate deeper learning as students progress through the chapter. Introductions typically involve a set of introductory questions, which can be used to trigger an initial discussion or a brainstorming session. They are followed by a brief discussion of the provenance of the texts (‘Over de teksten’).

Texts (teksten)

Each chapter contains one or more texts with an average length of 1,300 words per chapter. The readings are carefully graded. Chapters towards the beginning of the reader are usually shorter, and those towards the end longer and more complex. The texts are of a recent date and are taken from a range of both Dutch and Flemish media, such as newspapers, magazines, specialist journals, novels, collections of poetry, and the Internet. The topics relate to both Dutch and Flemish language, culture and society. This will expose students to a wide variety of topics, as well as a wide range of language uses in both the Northern and Southern parts of the Dutch language area.

Vocabulary lists (woordenschat)

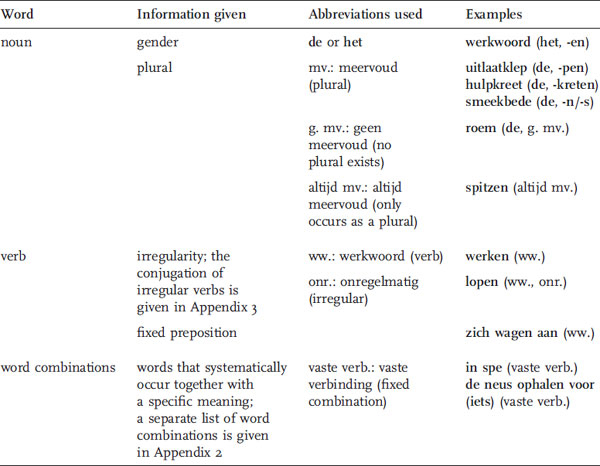

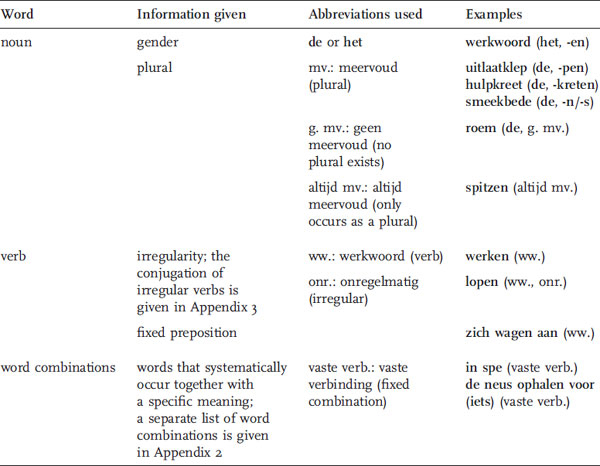

New vocabulary is marked in the text and translated in the vocabulary lists. Each entry is accompanied by a sample sentence in which the word is presented in a relevant context. In order to keep the glossaries manageable, we have limited ourselves to mentioning (1) only the meaning of the word or word combination in the given context, and not all meanings that the word or word combination could have, and (2) only the most important of the grammatical characteristics of the word or word combination as detailed below.

The comprehension of the text is trained in a variety of ways such as yes/no statements, multiple choice questions and open questions. Some of the open questions are factual, but others are interpretative. Since no correct answer exists for the latter, no answer is given in the answer key.

Vocabulary exercises (woordenschatoefeningen)

A person’s vocabulary is a complex structure that involves referential meaning as well as connotations, syntactical and morphological characteristics, and an idea of how the words relate to other words in the person’s vocabulary. This takes the form of a networked structure. The vocabulary exercises are designed to facilitate the construction of new mental models that fit in this existing networked structure. The exercises include:

–relating words to each other that have a common element of meaning (e.g. finding the odd one out and explaining why, or finding synonyms and antonyms),

–contextual exercises (e.g. filling in words from the glossary in sentences with a rich context),

–and exercises to learn and apply strategies for dealing with unknown but morphologically related vocabulary (e.g. discovering the meaning of a word by analysing compounds, exploring pre- and suffixes, or discovering derivations of words such as adjectives based on verbs and nouns).

The last vocabulary exercise of each chapter is designed to repeat vocabulary that occurs in the previous chapters of this reader. These exercises are clearly indicated as ‘herhalingsoefening’. They focus on verbs, nouns and fixed combinations that occur in the three previous chapters. The ‘herhalingsoefening’ in Chapters 5 and 10 also focus on adjectives. Students who are working on a selection of chapters from this reader may wish to skip these exercises since they deal with vocabulary they may not have encountered.

Students are encouraged to make use of dictionaries, such as the printed dictionaries by Van Dale, Prisma and Routledge, or free online dictionaries such as:

–http://www.encyclo.nl, which includes synonyms and antonyms,

–http://en.bab.la/dictionary/, which provides sample sentences with a translation,

–and the on-line Van Dale, http://www.vandale.nl, which offers both a free service and paid subscriptions to more comprehensive online dictionaries.

Students are also encouraged to use dictionaries of proverbs such as http://www.spreekwoord.nl and http://www.woorden.org/spreekwoord.php.

Speaking exercises (spreekoefeningen)

The speaking exercises are designed for pairs or groups of students to discuss a topic relating to the theme. The exercises are set up in such a way that students are stimulated to use the vocabulary offered in the glossary and vocabulary exercises. The speaking exercises range from informal to more structured discussions, and include presenting plans and ideas using presentation software such as PowerPoint, and making audio and video recordings.

Internet-based tasks (Internetresearch)

The fifth section of each chapter contains between three and six tasks in which the students are asked to do their own research on the Internet into background issues that emerge from the texts. The issues are chosen to increase insight into the language, society and culture from the Netherlands and Dutch-speaking Belgium. These tasks contain no instructions on how the results of students’ research should be communicated. This allows for flexibility in classroom situations: tutors can determine the nature of our Internet-based tasks with the specific needs of the current group of learners in mind. The tasks could be presented as writing or speaking exercises, using either formal situations (such as short reports or presentations), or informal ones (such as emails or unstructured discussions).

Suggested further reading (verder surfen en lezen)

Finally, each chapter ends with suggestions for further reading, predominantly on the Internet. The aim is to encourage students to further explore the topics discussed in the texts, and to allow them by means of extensive reading to further consolidate the new vocabulary and their newly acquired understandings of the culture, society and language(s) of the Low Countries.

We hope that you will enjoy using this book.

Note

1This paragraph is based amongst others on Mondria, J.A. (1996) Vocabulaireverwerving in het vreemdetalenonderwijs: de effecten van context en raden op de retentie. PhD thesis Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, and Laufer-Dvorkin, B. (2006) ‘Comparing Focus on Form and Focus on FormS in second-language vocabulary learning’, The Canadian Modern Language Review 63.1: 149–66.