Throughout the Tin Machine period and for some months before that, Bowie had been in negotiation with a handful of record labels concerning the reissue of his back catalog. Back in 1971, when then-manager Tony DeFries signed an unknown David Bowie to RCA, one of the clauses in the contract said that, after fifteen years, all rights would revert to what was then the solid partnership of artist and management. Bowie’s relationship with DeFries had perished long before that span was up, but the terms of the contract remained in place.

In early 1987, fans began to notice that the Bowie shelves in their local record store were contracting at a fearful rate — fearful, that is, because the mid to late 1980s were the dawn of the CD age, a time when every significant catalog of the past thirty years was being remastered and reissued in the shiny new format.

RCA had indeed pumped most of the Bowie titles out into the digital domain, but the process had been slow, the pressings were small, and a lot of would-be purchasers were still trying to decide whether they wanted to bother with CDS at all. It wasn’t the first time a new format was thrust into the marketplace in an attempt to conquer vinyl, and it wouldn’t be the last. Of course people were suspicious, Bowie fans no less than any other. Add to that conundrum the positively abysmal sound quality that afflicted the CDS that RCA had released. By the time they realized that, on this occasion, the prophets (or should that be profits?) were correct, and CDS were taking over, the supply of Bowie titles was contrarily drying up. Within a year or so, even the specialist shops were having a hard time dredging up copies.

Bowie was aware of the problem, but he was also unwilling to rush fresh supplies of CDS back into the marketplace to feed the growing demand. More than many artists, he had always been conscious of the collectors’ market. As far back as 1972, before he’d even followed up the breakthrough hit “Starman,” he’d authorized reissues of two of his older albums, Space Oddity and The Man Who Sold the World. In the years since then, he ensured that at least a trickle of peculiar rarities kept his devotees on their toes: a disco version of “John, I’m Only Dancing,” recorded in 1974, but not released until 1979; a triumphant take on “The Alabama Song,” taped in 1978 but archived in 1981; Ziggy’s legendary farewell concert, held back for a decade before finally seeing daylight.

Now it was time to undertake a full-tilt scouring of the archives; and, as his own thoughts for the forthcoming reissue program melded with those of the labels with whom he was talking, so a mass of new notions began to accumulate.

Among the sticking points in many of the negotiations was Bowie’s insistence that the reissues remain full-priced, in contrast to the budget and mid-price releases that other artists were receiving. Few of his suitors agreed with him — perhaps surprisingly, there was little industry confidence in his belief that people could be persuaded to buy the same record again without some kind of financial inducement.

One company that did agree was Rykodisc, a comparatively tiny Massachusetts-based label that had recently enjoyed considerable success with their handling of the Frank Zappa back catalog. In fall 1988, label cofounder Rob Simonds announced that he was close to striking a compromise deal with Bowie. “We’re willing to put it all out at full price, if Bowie [will] make extra material available to us. We’ve done a lot of research and . . . apparently there’s a ton of unreleased stuff.”

Bowie agreed. Bonus tracks are a staple of the reissue industry today. But when Rykodisc outlined a dream scenario that might include a box set divided between familiar favorites and long-legendary rarities, with additional bonus tracks appended to each of the reissued albums, they were inviting Bowie to journey in a direction that precious few “major” artists had even considered at that point. As well, it would boost the sales potential of the reis-sues. So what if you’ve already got Ziggy Stardust on the RCA CD? You don’t have it with a bunch of extra songs, do you?

“It’s in the hands of the lawyers now,” Simonds said that October, and he acknowledged, “It’ll be a big challenge tracking down where all this stuff actually is.” The label had already sniffed out details of various tracks “that are supposedly in some-body’s vaults somewhere,” while Bowie himself had conceded that much of his unreleased archive was only on the shelf because “there wasn’t enough room on the [original] records to put it out.” Indeed, said Simonds, “he really showed enthusiasm, he was really into the concept.”

And so he was. In and around his Tin Machine duties, Bowie spent much of his time playing through the tapes that, for years now, he’d been storing in Switzerland. They did not encompass his entire career. The original masters for Space Oddity and The Man Who Sold The World had somehow disappeared. He remembered recording other performances, but could not locate the tapes. A wealth of further material, meanwhile, simply didn’t appeal.

Over time, however, and in cahoots with Rykodisc, Bowie amassed a staggering haul of no less than fifty tracks that could reasonably be considered rarities, ranging from the acoustic “Wild-Eyed Boy from Freecloud” that backed the “Space Oddity” hit in 1969, through to the then-newly taped take on “Look Back in Anger” that had marked the ICA benefit.

And that was before he even started playing through the hours and hours of unreleased material that dated from the Berlin sessions that had produced Low, “Heroes” and Lodger. He informed Rykodisc that there were probably another fifty songs in that stockpile alone; and, though much of it lay incomplete, still he pledged to plow through it, and make available what he could.

The Rykodisc deal was closed in March 1989 as Bowie prepared to launch Tin Machine; now, as the first chapter in that band’s career closed (their final show, in Livingston, Scotland, fell on July 3), it was time to readdress the library of work that had come before . . . and, in so doing, essentially undo everything and anything that Tin Machine had managed to achieve. For six months, Bowie had pretended that his past didn’t exist. For the next however many months, that’s all there would be: the past.

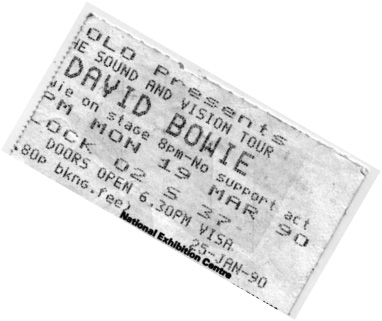

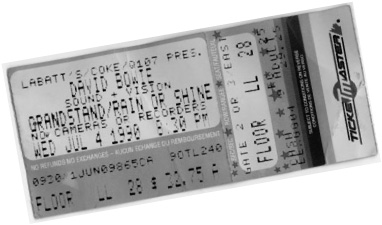

Rykodisc’s reissue program commenced in August 1989 with the release of the four-CD Sound + Vision box set. It would be available in the U.S. alone (incredibly, Bowie had yet to conclude any kind of UK deal, and would not do so until the end of the year, when he finally reached agreement with EMI), but even before the package’s contents were confirmed, Rykodisc project manager Jeff Rougvie was enthusing, “some of this stuff is pretty amazing.”

He spoke glowingly of a version of Cream’s “I Feel Free,” dating from the Scary Monsters sessions; a couple of Bruce Springsteen covers that had eluded even the bootleggers; a here-we-are-in-the-living-room demo of “Space Oddity”. . . and that was only the start.

Bowie’s entire RCA catalog, a total of sixteen albums, would be reissued chronologically in groups of three, spread over the next two years, with almost every one bolstered by bonus tracks . . . four, even five apiece. It was an ambitious project. The first reis-sues began appearing on the shelves: Space Oddity, The Man Who Sold The World, Hunky Dory. Although such gifts have since become an industry standard (and Bowie himself has upgraded the catalog at least once since then), the true possibilities and potential of the Compact Disc were finally made apparent to the last suspicious holdouts. It wasn’t simply a matter of replacing your entire record collection — you could reshape it as well.

A lifetime away — Bowie at the “Be My Wife” video shoot, Paris 1977. (© PHILIPPE AULIAC)

Any project such as this was bound to have its critics. It really didn’t take long for the complaints to start rolling in, with the most vituperative focusing on the handful of oversights that, perhaps inevitably, popped up as the series moved on: a misplaced outtake here, a mislabeled remake there . . . or was it the bootleggers and fanatics who were wrong?

Certainly, Jeff Rougvie had little patience with a lengthy feature in the American collectors magazine Goldmine in December 1990, that outlined the commonest complaints about the series, or, as he preferred to call it, “the ‘Bowie-fiction’ that has made my task responding to the fans’ enquiries a sometimes frustrating effort.”

It was astonishing just how many assumptions had become accepted history; how many songs originally recorded for one album that were somehow credited to the sessions for another. One of the joys of the unfolding reissues was that it finally corrected a universe full of fanzdom misconceptions.

But even Rougvie was forced into the occasional corner, as when he attempted to explain the absence (from Aladdin Sane’s reissue) of “All the Young Dudes,” a performance that had been cropping up on bootlegs for a decade, and which was even discussed in one of the best-selling rock books of all time, Ian Hunter’s Diary of a Rock and Roll Star.

As the front man for Mott the Hoople, Hunter sang the hit version of “Dudes,” in the summer of 1972. Six months later, Bowie played him his own newly recorded attempt at the song. It was slower and sax drenched, Hunter reported, and he admitted he didn’t especially like it. Neither, it transpired, did Bowie. The song was archived, but surely not so deeply that Rougvie would be forced to write, “I’m not convinced that there ever was a real studio recording of ‘All the Young Dudes,’ as every tape I ever got claiming to be the studio version was actually the radio session with the intro clipped off.”

Of course, a readership full of hitherto sympathetic readers suddenly leaped back to ask “What radio session?” Bowie had never recorded that song for any radio broadcast.

Luckily, the years since the Rykodisc series came and went have answered most of the questions that attended the original issues. Besides, it was a lot more fun at the time to revel in the songs that were included than to bitch about the ones that weren’t: the appearance, for example, of a Ziggy Stardust outtake (“Sweet Head”) that had never been mentioned in print before; or a Diamond Dogs demo that may have shared its title with a track on the finished album (“Candidate”), but which was, in fact, a different song altogether.

Those were only the most revelatory of the series’ discoveries. With the exception (again) of the unadorned Aladdin Sane, almost all of the reissues were worth picking up for the bonus tracks alone, at least until you hit the later ones. The Berlin stockpile turned out to be a considerably smaller harvest than Bowie had hoped; and we’re still waiting for that version of “I Feel Free” to be released.

Bowie’s involvement with the reissues was not restricted to approving the bonus material (it was he, according to Rougvie, who insisted the “wrong” version of “Holy Holy” be appended to The Man Who Sold the World, because he “feels the later take is superior”). But the surprises were not confined only to the record racks. That became clear on January 23, 1990, when Bowie announced his plans for the next year. Most bands are content with a greatest hits LP. He was planning a greatest hits tour.

Reeves Gabrels would have been quite happy to see the entire Tin Machine experience knocked on the head after the first album. Even before the band reconvened, he was convinced that heading back into the studio for a second album really was over-egging the soufflé. But the Sales brothers weren’t simply enthusiastic for more, they demanded it. And, in a democracy, the majority rules. Work on a second Tin Machine album kicked off in September 1989. Shifting their base of operations to Sydney, Australia, for the duration, the group entered the studio, with the shock of first-time-around success still ringing triumphantly in their ears.

The intention this time, Gabrels believed, was to cut a record that owed more to songwriting than to simply playing loudly; and so, after a fashion, that’s what they did. Except the songwriting itself to prove as divided as were the band’s other duties.

Across Tin Machine, Bowie had held on to at least a modicum of the compositional credits for every song on the album, whether cowriting with Gabrels or Armstrong, or simply pitching in with the full band. This time around, however, he wanted his band-mates to take some of that heat away. Hunt Sales alone availed himself of the opportunity, handing in the road-broken “Sorry” and the bulk of “Stateside,” and the drummer then took the lead vocal on both songs.

Other songs were somewhat less contentious in terms of authorship, if not delivery. Occasionally, Bowie even allowed himself to relax a little. “Amlapura,” a song he wrote during a visit to Bali that summer, would provide shockingly beautiful counterpoint to the barrage of “Baby Universal” and “You Belong in Rock’n’roll,” while the decision to cover Bryan Ferry’s “If There Is Something,” a gem from Roxy Music’s self-titled first album, offered up a rare example of Bowie paying homage not merely to one of his own favorite artists, but to a career-long rival.

In 1972, Roxy came as close as anyone could to upstaging Bowie’s own rising star on more than one occasion, while the following year saw Ferry actually consider injuncting Bowie’s Pin Ups album, so closely did it echo (some unkindly said “pillage”) the widely publicized plans for his own solo covers collection, These Foolish Things.

But Bowie’s admiration of Ferry was also well known. Another song from Roxy Music, “Ladytron,” was at least rehearsed during those same Pin Ups sessions, while the very fact that Ferry, almost alone among Bowie’s glam contemporaries, had weathered the ensuing decades with equal panache, laid a bond between the two men that their public, at least, had long ago recognized.

No matter that a once-beautiful song was suddenly reduced to a proto-industrial clatter, covering “If There Is Something” was one of Bowie’s most egoless acts ever. One can only imagine how it might have emerged had Bowie and Ferry only followed through with their rumored intention to duet on a rerecording of the song. In the end, Bowie contented himself with transforming that most plaintive of love songs into a virtual blackmail note: “I will put roses round the door,” he sang, “And grow potatoes by the score.” So there.

Elsewhere, the Tin Machine sound remained loud and rambunctious, the mood of the lyrics forthright and confrontational. Despite taking its title from American television’s favorite talking horse, “Goodbye Mr. Ed” gave Bowie an opportunity to graze the modern American landscape from a very different perspective from the one he historically employed. Usually he observed, this time he condemned.

But it was “Shopping for Girls” of which he (and, by association, both Gabrels and wife Sara Terry) was proudest, as the lyric came hurtling out of experiences that she had relayed to Bowie while they traveled together on the Glass Spider tour.

For six months before she took on R duties for that venture, Terry was working alongside another reporter and a photographer on Children in Darkness: The Exploitation of Innocence, a Christian Science Monitor investigation into the exploitation of children in developing countries. It was a journey that saw the team visiting child prostitutes in the Philippines and Thailand, child workers in the silver mines of South America, child soldiers in Uganda and more.

Gabrels joined her at some of the halts. His own musical education, he later reflected, took a major boost from “going to India and Kashmir, being around all the people . . . actual snake charmers. And I’m just sitting there listening to these guys and recording them on a little Walkman. That had a big effect on me. Never having been entirely comfortable with a twelve-tone system anyway, or an eight-tone diatonic system, and never understanding why, and feeling like I shouldn’t really be doing this because I’m not playing the right notes . . . . I thought I shouldn’t be playing an instrument at all. But all of this gave me new courage.”

He would need courage, and not only in his music. Voyaging into some of the most tightly controlled regimes in the world, the team was constantly on guard for attack and sabotage. The eight-week break that Terry was offered by the Bowie tour was, as her husband put it, a time in which she could “balance out the horror of the reality of the previous months . . . [for] what could be further removed from reality than a rock tour?”

What she had seen, however, remained with her, and the tales that she passed on to Bowie in conversation would shake him, too, and it would later be spit out in the frightening bitterness of “Shopping for Girls.” No matter how deafening the roar that Tin Machine set up behind the song, the lyric remained louder still.

The sessions stretched on through the remainder of the year, a routine that was broken only by a one-off show down the road from the studio, at Sydney’s Moby Dick’s club. Unannounced and unexpected, it allowed the group to burn through the entire new album without apology or explanation; one witness to the performance even admits that he didn’t actually know who the band was, not until the lights hit the singer in a certain way and recognition finally flashed.

But although the album could, and probably should, have been completed then, Bowie’s own plans for the new year rendered it an all but irrelevant exercise.

Although the notion had certainly been discussed before, it was the release of the Sound + Vision box set, and the attendant reissues, that finally prompted Bowie to take the plunge and announce, on January 23, 1990, a greatest hits tour of the same name.

“It’s been thrown at me for some years,” he confirmed at a London press conference. “Audiences and . . . producers of rock shows, who’ve said ‘why don’t you just go all the way and do all the songs that they know? You’ve never done it, and it’d be great.’”

In the past, Bowie’s instinct had always been to recoil from such a concept. Even if it didn’t quite reek of Caesars Palace–style desperation, it would still be “corny.” It was Rykodisc’s enthusiasm for the reissue program that finally convinced him otherwise. “I gave in . . . when Ryko said ‘it would be great if you would help support this thing.’”

Bowie agreed, but then lay down a condition of his own. He’d do the tour once, but he would never do it again, at least not with these songs. For every one of the numbers he performed, he said, it would be the last time. “That would give me a motivation for the entire tour, knowing each night I do them, I get that much closer to never singing ‘ground control to Major Tom’ again.”

It was not going to be the easiest of separations. “I know I’ll miss them desperately,” he confessed. “They’re very fine songs to work with, and I love singing most of them. But I don’t want to feel that I can always fall back on them.” Even more importantly, however, he didn’t want audiences to feel he would always fall back on them. How invigorating it must have felt being on the road with Tin Machine, knowing that “The Jean Genie” and “Rebel Rebel” were not on the menu. And there had to be a definite thrill in the knowledge that they might never be again.

Bowie never went so far as to categorically pledge that the old songs were dead — remarks like that do have a habit of creeping back to bite you. Rather, like a skilled politician, he gave the strong impression that that was the case. He was placing the songs “behind him,” he said, and that was sufficient to engender a sense of finality to the proceedings.

There was just one hope of reprieve left for the condemned tunes. With extraordinary glee, Bowie made it clear that he himself was not going to choose the songs. Rather, he was launching an international telephone poll, for fans to call in and vote for the songs they most wanted to hear one last time.

It was a gesture that lay wide open to abuse, and the British New Musical Express newspaper was quick to rope its readers into taking advantage of that, recommending that they all call up and request “The Laughing Gnome,” the 1967 novelty song that, to the utter mortification of all who worshipped Bowie, was reis-sued in the summer of 1973, to become one of his biggest hits ever.

Bowie himself was in on the joke. At the press conference, he even sung a few lines of the gnomish anomaly, before sweeping into a majestic “Space Oddity.” But, despite NME readers’ best efforts, the song did not make the final cut, and Bowie probably wouldn’t have paid attention if it had.

Although the bulk of the Sound + Vision set would be drawn from the phone poll, rehearsals for the tour kicked off in New York long before the results were in, with nobody in any doubt as to what the final results would be: “Space Oddity,” “Life on Mars?,” “The Jean Genie,” “Rebel Rebel,” “Fame,” “TVC15,” “Heroes,” “Let’s Dance” and “China Girl.” Into this, Bowie then injected a few songs that he himself fancied performing: “Queen Bitch,” “Station to Station” and “Be My Wife,” among others.

Still buoyant from the Tin Machine tour, Bowie’s initial instinct was to retain Reeves Gabrels as the heart of a similarly slim-line, four-piece band for the tour. Gabrels turned him down. He may not have wholly supported the notion of extending Tin Machine’s lifespan beyond one album, but now that the decision had been made, the separation between the band’s career and Bowie’s solo activities had to be maintained. Plus, it was hardly going to thrill the Sales brothers if he was involved and they weren’t, although it would have been interesting, everybody agreed, for the full Tin Machine lineup to have regrouped for this tour as well. Interesting, but impractical.

Gabrels returned to London and a daybook full of occasional session work (alongside Tim Palmer, he appeared on The Mission’s Carved in Sand album later that year); and he mused once again on the possibility of abandoning music for a career in law.

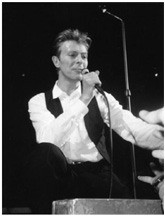

Flashback! Looking awfully like the old Thin White Duke, Mr. Sound + Vision in Birmingham, 1990. (© GRAHAM MCDOUGALL)

Bowie, meanwhile, reimmersed himself in the pool of musicians with whom he’d worked in the past, and plucked a more or less fully formed unit from there. Erdal Kizilcay was recalled from the ICA benefit to play bass. Adrian Belew hailed from even further back, from Bowie’s days in Berlin, and he tells an amusing tale of one of their earliest encounters, in 1978.

Belew was gigging with Frank Zappa at the time, and Sheik Yerbouti, Zappa’s then gestating next album, was already shaping up to be a veritable showcase for the young ingénue. Certainly, Zappa was not at all happy to be losing his star discovery, and, once it became clear that Belew had agreed to join Bowie’s band, Uncle Frank insisted on a clear-the-air meeting, at which he insisted upon addressing his rival as “Captain Tom.”

Unquestionably, however, jumping ship to Bowie’s band was the right move for Belew to make. Shining brightly throughout the ensuing world tour, providing one of the few genuinely bright sparks on the ensuing Stage live album, Belew remained onboard for Bowie’s Lodger, before spinning into sessions alongside fellow Bowie collaborators Eno (when he produced the Talking Heads’ Remain in Light) and Robert Fripp (with the re-formed King Crimson).

Stylistically, Belew was a unique guitarist, if something of an acquired taste. His detractors, and there are many, refuse to accept his sound as actual guitar playing. “He labors under the delusion that weird guitar noises are automatically art” Melody Maker once complained. “So you know why Bowie loved him,” critic Amy Hanson later remarked.

Visually, too, Belew had a lot to answer for. He may not have been the first musician to shave away his eyebrows and don a skinny tie, but he was certainly the first to spark a fad for such adornments, and the video record of the early 1980s is as littered by examples of his look as the music of the age was dominated by his sound.

Reeves Gabrels himself admits that, were it not for a sighting of Belew in 1980, his own playing might have been very different. At first, he was firmly in the thrall of the great rockers Jeff Beck and Lesley West on the one hand, and the jazzy Carlos Rios and John McLaughlin on the other.

“Then I went to see Adrian with Talking Heads at the Orpheum Theatre in Boston, and suddenly music didn’t just exist on an X/Y axis. It wasn’t just two-dimensional, there was a third dimension. I remember coming home at the time and looking at my Franken-Strat, which was a ’73 Les Paul Deluxe Gold Top and a Strat that I’d put together from spare parts, which I still have . . . and I remember just looking at the guitar in the corner and saying ‘What the fuck was he thinking?’ It was like suddenly it’s not just harmony and melody, it’s like there’s this other thing that’s both of those things but spread out in a very three-dimensional, Dali-esque way. And that’s where the change started.”

Belew picked his guest appearances carefully. He was as likely, in fact, to be found gigging with his own band, The Bears, as propping up new releases by Crimson, XTC and Tom Tom Club, while 1982 saw him cut Lone Rhino, the first in a succession of remarkably eclectic, if challenging, solo albums.

Now he was hard at work on his fifth, Young Lions, and Bowie readily agreed to guest-star on the record — his way of thanking Belew for agreeing to join the new tour. Belew had offered up several of his own compositions for Bowie to appear on; Bowie, in turn, responded by mailing him a tape of “Pretty Pink Rose,” one of the songs he’d abandoned in L.A. in early 1988. By the time the session was over, however, Bowie had also grasped one of Belew’s originals, an instrumental titled “Gunman,” written an entire lyric for it, and laid down a finished performance, all within half an hour.

It was as Bowie listened to the playbacks that he realized the unit Belew had built around himself sounded precisely how he had envisioned his own tour coming across. With drummer Michael Hodges and keyboard player Rick Fox in brilliant form, there was a remarkable edge to the band’s playing: the teetering sonic fission that Belew naturally brought to almost every project he was involved in, but there was also a dissonant frenzy, “the air of unfamiliarity” with which Bowie insisted on imbuing the revivals.

Both players were brought into Bowie’s band, there to be told the same thing that the singer had already told the world’s press. He didn’t want to “have to think myself back to rediscover what I was on about in any of those songs,” he insisted. “I’m approaching [them] strictly from now.”

Adrian Belew onstage during the Sound + Vision tour. (© GRAHAM MCDOUGALL)

Bowie confirmed these aims with plans for his next single. Although a fresh greatest hits compilation, ChangesBowie, was inevitably scheduled to accompany the tour, he also felt the need to offer something fresh to the project. The masters for “Fame” were surrendered to a clutch of the era’s hottest remixers, Arthur Baker, Jon Gass and Dave Barrett among them, to be layered with the very best that modern technology could offer, regardless of whether the original’s slinky rhythms required such adornments.

The results, spread across a bewildering succession of “Fame 90” releases in March as the tour kicked off, were unlikely to satisfy anybody who retained any fondness for the original 1975 recording. Indeed, though Bowie was dead on when he pointed out how this “nasty, angry little song . . . [still] stands up really well, still sounds potent,” the best that can be said for the remixes was that they sounded good at the time. A few months later, though, they were already horribly dated.

“Fame 90” was the only serious misstep Bowie made as the Sound + Vision tour took shape. Belew confirmed his own satisfaction with the proceedings in an interview with International Musician magazine. “I wanted the band to sound very plain and unadorned. [But] I also wanted them to go from sounding like an orchestra for ‘Life On Mars?’ to sounding like a garage band for ‘Panic In Detroit.’”

Bowie envisioned a stage set to match these sonic panoramas. Chastened by the sheer logistics required by the Glass Spider, he looked back, instead, to the Station to Station tour, where it was lights that dictated the show’s ambience, not dancers, ropes and massive arachnoids. “I want to keep the stage as minimalist as possible,” he told MTV. “I really wanted it to have the feel of an opera or a ballet stage, where it was just one large dark space that could be lit in a theatrical fashion.”

That is not to say there would be no frills. Choreographer Edouard Lock returned to the scene, this time to design the dance routines that would be projected onto the vast panels of gauze that rose and fell throughout the performance, activated via a computer linked to the keyboards. With Louise Lecavalier, Bowie’s partner at the ICA benefit, reprising her role, and the rising directorial star Gus Van Sant supervising the actual filming, the ensuing series of forty-by-fifty-foot video images reminded Bowie, he said, “of an enormous Javanese shadow puppet show.”

The now-defunct UK music paper Melody Maker caught the Sound + Vision tour’s opening night at La Colisée in Quebec City, Canada, on March 4. It was a serendipitous move. Twenty-nine years earlier, that same paper arguably laid the first stone of Bowie’s then-unimaginable fame when it published the interview in which the singer announced he was bisexual. Now, although the circumstances were vastly different, the same paper was to witness the opening night of Bowie’s attempt to finally close the door upon all that had been unleashed back then.

They say nothing is new in show business. Bowie himself once acknowledged that it doesn’t matter who does something first, “it’s who does it second” that people pay attention to. And so the Sound + Vision stage set had any number of precedents, within Bowie’s own canon and within others’. Wendy Carlos’ electronic rewiring of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy,” as fermented through the soundtrack to the film A Clockwork Orange, was revived from the Ziggy Stardust era to open the show; a giant screen projection of the singer’s face (in this case, counting down the introduction to “Space Oddity”) had once been a staple of Mott the Hoople’s live act; and Bowie was certainly not the first performer to pick up a camera and begin filming the audience, while they gazed back up at him — Peter Gabriel was doing that back in 1973.

Another pattern from the past was the decision to hide the bulk of the band out of sight for large portions of the show — not the entire evening, as sundry subsequent accounts have insinuated, but enough, apparently, that Rick Fox came close to quitting the tour on several occasions, so unhappy was he with the obscurity.

It was a move — and mood — that Bowie had first broached back in 1974, on the Diamond Dogs tour. Back then, too, it was close to disastrous, as the players (perhaps understandably) balked at their anonymity, but at least Bowie could blame the stage set for the decision. “They kept saying ‘we don’t like playing behind these bleeding screens,’ and I said, ‘well, you’ve got to, because I haven’t got any parts for you.’” The stage was designed to resemble a city street, which it certainly would not, “if there’s a bass amp stuck in the middle.” This time around, he had no such excuses; and, strangely, Belew alone was visible to all of the audience, all of the time.

Erdal Kizilcay, meanwhile, allegedly came just as close to being fired, after he thought he saw Bowie gesture “come here” midway through the show, and did so. It turned out Bowie had intended nothing of the sort, and was both stunned and horrified to see his bassist suddenly march out to the front of the stage and begin dancing with him.

To isolate such moments of discord as being somehow characteristic of the show (again, as some writers have done) is of no service to anyone — just as pointing out familiar flashes in the visuals only causes one to overlook all that was new and innovative. From the rotating police lights that bathed “Panic in Detroit” in blood, to the then-and-now symmetry of “Life on Mars?” as Bowie sang beneath a screen showing the song’s own 1973 video, Sound + Vision lived up to its name from every conceivable direction.

Lit from beneath, Bowie’s performance of “Station to Station” returned him to the slick-haired, Thin White Duke of the mid-1970s; wrapped around Louise Lecavalier, he finally imbued “China Girl” with the sexuality that his 1983 stab had left in the icebox. “The crowd are amazed.” Melody Maker’s opening night review reported, “No one has ever seen anything like this before.”

Naturally, there were knives to be sharpened as the tour marched forth. Those critics who refused to believe that Bowie had ever told the truth in his life, wrote the entire affair off as a callous money-making operation; there was the star’s tacit acknowledgement that his new songs sucked, so here’s the oldies instead; and it was worth noting that only three songs in the entire show (“Let’s Dance,” “China Girl” and “The Blue Jean”) hailed from any of his post-Scary Monsters albums.

The band, too, was slighted. Though Bowie himself played more guitar and saxophone than he had on any preceding tour, there was still room to criticize the less than dramatic sound of the quartet behind him. Bowie’s decision to be unlike other acts who toured with vast ensembles was seen as simply that, a deliberate attempt to be different.

Sequencers, as well as Belew’s own staggering array of guitar synths, filled in a lot of the gaps, as did a succession of bold new arrangements. The fretless bass that played behind “Space Oddity” was revelatory, while Belew’s contributions included a magnificent backward guitar fanfare for “Ashes to Ashes.” But, while the nature of the musicianship was starkly dissimilar to Tin Machine, more than one writer compared the setup, and now they wondered why Bowie hadn’t simply brought his bandmates along instead. Bowie had said, after all, that he was searching for something “stripped down . . . a keyboards, bass, drums, lead guitar interpretation of the songs that I’ve done over the years.” Tin Machine could have offered that, and gone hell-bent for leather in the instrumental breaks, too.

Naturally, no amount of critical carping could dampen the public’s enthusiasm for the tour. Bowie’s audience, too, had been bitten more times than they could count by his intemperate pronouncements, going all the way back to his announcement in 1973 that he was quitting. But there was always the chance that he was telling the truth, and the extended life of Tin Machine convinced many that he was. Well, either that, or he’d finally flipped his lid. In March, a pair of shows at the 12,000-seat London Arena, newly opened in the heart of the city’s rejuvenating docklands area, sold out so quickly that a third show was promptly added, and that sold out in a record eight-and-a-half minutes.

Two more UK gigs at the massive Milton Keynes Bowl in early August fared just as well, while halts elsewhere around the world, across the United States, Canada, Japan, Europe and South America, dwarfed even that venue’s vastness. Bowie could still remember, back in May 1973, the first time he played one of those Brobdingnagian arenas — at least, it felt that way at the time — the 18,000-seater Earl’s Court Arena in London. Afterward, he’d asked if such places were really necessary.

Now he was facing venues five times that size. There was one Dome in Tokyo that could seat a small town, and others that so dwarfed their surroundings that it made one wonder where they even found enough people to fill them. One evening as they prepared to go on stage, Bowie turned to Belew and shuddered, “I stretch my arm out and look to the right and I see there’s my friend Jim over here. I wave and two thousand people wave back.”

The question he sometimes asked himself, however, was where did those 2,000 people come from? The previous year, as the Rolling Stones lurched into their Steel Wheels tour of America, an entire new audience demographic seemed to have come into play, crowds who were fans of the band only in as much as they liked the old hits, had bought the odd compilation, and were simply looking for a night out with music they remembered. This was not a “gig-going” audience at all, but rather one that was looking to take part in an event.

These were the people who, in later years, would attract the scorn of the “true faithful” (and Bowie himself) with their ignorant response to his playing “The Man Who Sold the World” in his live show — “Cool, he’s covering a Nirvana tune”; who thought Tin Machine were called Tin Man; and who were convinced Iggy Pop was an English soft drink. Adrian Belew later condemned “a certain portion of the audience that knew less about David Bowie than the true David Bowie fans,” although the corollary to such complaints was: how many true David Bowie fans were actually left out there?

As so many observers pointed out, it had been ten years since Bowie last released an album that his fans considered worthy of his name (Scary Monsters). Since that time, no matter whether anyone actually liked the records that pocked the eighties, he had done very little that even threatened to match his earlier output. And even the most loyal audience will run out of patience sooner or later . . . or run out of time to fritter away on past amusements. The audience Bowie gathered to his breast through the seventies was now staring thirty in the face: if you were twelve when you fell in love with “Starman,” you were already there. Frankly, there were a lot of things that mattered more in life than wondering just how badly Bowie would trample your memories this time around.

“Oops, do you think they noticed?” Frejus Arena, 1990. (© PHILIPPE AULIAC)

So, the hardcore gave way to the casuals, and that cuts both ways. On the one hand, you have an audience that is going to squeal with uncontained delight at every intro they recognize; on the other, you’ve got an army that wants to recognize every one. As the tour rolled on (it would ultimately play one hundred and eight shows in twenty-seven countries before finally closing at the Rock in Chile Festival in September), swaths of the set list were quietly dropped, as Bowie read his reviews, listened to the audiences and, out of deference to a throat complaint that had apparently been bothering him throughout the tour, shortened the show by removing virtually any song that didn’t have at least a gold disc behind it.

When The Guardian’s Adam Sweeting described the show as Bowie’s own Antiques Roadshow, he wasn’t merely being facetious. The entire set now was gilt-edged and glittering, and there was more than one moment when, though it was fun to hear a particular song being performed, one wondered how much better it would be had Bowie actually sounded like he was enjoying himself.

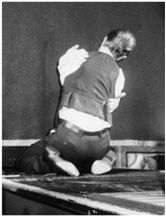

Still, there were also occasions that could give the most uninvolved onlooker a reason to smile, and that could reduce “true” fans to fits of ecstasy. All tour long, Bowie had taken a shine to one particular moment of “Young Americans,” taking the moment of silence that follows the line “break down and cry” and drawing it out to ever more extraordinary lengths. In New York, in front of a packed Giants Stadium, he fell to the floor as usual, then lay there without moving for more than two minutes of spellbinding silence.

It was, pronounced New York hardcore musician Richard Hall, “the coolest thing I’ve ever seen a musician do on stage”; and, a few years later, in his new guise as Moby, he told Bowie as much. Bowie remembered the moment well. “I just stayed there, just seeing how far I could take it.”

Other nights brought other surprises. In Japan, Louise Lecavalier and Donald Weikart, one of her partners in La La La Human Steps, joined the show, body-slamming around Bowie during a riotous “Suffragette City.” In Cleveland, U2 front man Bono appeared at the party, leaping onstage to breathlessly emote (what else?) his way through a sizzling duet of “Gloria”; and, in Brussels, birthplace of Bowie’s longtime hero Jacques Brel, the singer came close to treating the crowd to Brel’s own “Amsterdam”. . . close, that is, before he laughingly acknowledged that he’d forgotten the words.

And then there were the projections, an interactive potpourri that saw a fifty-foot Lecavalier rise up to chase the live Bowie off the stage, the computer-generated cutups that slashed a real-time image to ribbons, the disembodied giant legs that somersaulted through the lonely cosmos of “Space Oddity”.

“Gimme your hands” — Birmingham, 1990. (© GRAHAM MCDOUGALL)

Does anybody fall for that old trick any more? (© GRAHAM MCDOUGALL)

There were occasions, too, that made Bowie sound more relaxed than he had on any other tour in two decades, a very real and almost tangible sense that an immense weight was being lifted from his shoulders; that, just as he’d hoped at that press conference back in January, every night he sang a song, he was one night closer to never singing it again. Unless he wanted to. “I have the same freedom as all of us, that is, to change my mind, ha ha.”

Yet, behind the scenes, there was a turmoil that no amount of forward thinking could truly erase, and one that didn’t involve either the bad-tempered band or the day-tripper audiences. For close to three years now, since the conclusion of the Glass Spider tour, Bowie had been in a relationship with one of the dancers on that outing, Melissa Hurley. The liaison might even have started sooner than it did were it not for Bowie’s refusal to get involved, as one onlooker put it, “with the staff.”

It was an intriguing relationship, at least so far as the gossip columnists were concerned. He was over forty, she was still in her twenties. But they fell in love regardless, “while having a holiday in Australia,” Bowie said. “Such a wonderful, lovely, vibrant girl.”

The romance blossomed quickly. Soon, word was spreading that they were to marry; that they were already engaged. At the back of Bowie’s mind, however, there lurked a fear that simply wouldn’t quit, the dim awareness that the relationship was fast becoming “one of those older men, younger girl situations where I had the joy of taking her around the world and showing her things. But it became obvious to me that it just wasn’t going to work out as a relationship, and, for that, she would thank me one of these days.” Somewhere along the line, as Sound + Vision circled the globe, “I broke off the engagement.”