The tour ended in Buenos Aires on September 29, 1990, but Bowie was to find little time in which to relax. Off the road and on a film set, he slipped straight into preproduction for his next movie, a lead role in Richard Shepard’s Linguini (soon to be retitled The Linguini Incident and, the last time it was spotted, Shag-o-Rama.)

Financed by Bowie’s own management company, Isolar, Linguini was a deliciously lighthearted comedy about a pair of down-on-their-luck lovers, a waitress (Rosanna Arquette) and a waiter with a gambling habit (Bowie) who decide the only answer to their problems is to embark upon a life of crime. It culminates with the audacious theft of an antique ring that once belonged to Harry Houdini — Arquette’s character is an aspiring escapologist.

It was all very trivial, even banal, but it was funny, and it certainly had its moments. Indeed, though it was not quite Shepard’s directorial debut (1988’s Cool Blue had preceded it), Linguini was certainly responsible for setting him on the path that has established him among the most reliable of all modern directors, as subsequent efforts Mercy, Oxygen and The Matador all illustrate.

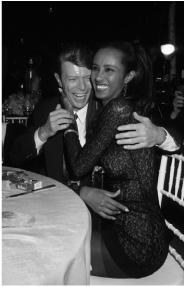

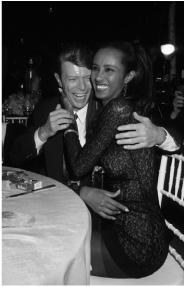

Somewhat typically, Bowie himself did little to promote the film. It was not reticence however, that held him back. It was romance. Just a few months after he and Hurley parted, and just two weeks after the last Sound + Vision concert, at a dinner party thrown by hairdresser Teddy Antolin in Los Angeles, Bowie was introduced to Iman Muhammid Abdulmajid, the thirty-five-year-old Somali who, throughout the 1980s, was arguably the best-known model in the world.

She had dropped out of modeling to launch her own cosmetics company (Iman Cosmetics) and venture into movies. Bowie later laughed that the moment he first clapped eyes on her, “I was already naming our children.”

A decade later, he told the Sunday Times, “It was so lucky that we were to meet at that time in our lives, when we were both yearning for each other. She is an incredibly beautiful woman, but that’s just one thing. It’s what’s in there that counts.” And that, Iman continued, was “the wonderful realization that I have found my soul mate, with whom sexual compatibility is just the tip of the iceberg. We have so much in common, and are totally alike in a lot of things.”

He outlined some of those similarities as he penned the fore-word to Iman’s autobiography, I Am Iman: “we’re both skinny, and we both get up at 5:30 in the morning.”

His new love’s very name had an impact on him. When Bowie was seven, his half-sister Annette had left England to live with her Egyptian husband in his home village. Converting to Islam, she took a new name of her own: Iman.

Bowie’s first public gift to this new Iman in his life was a cameo role in Linguini. Shortly after, as he returned his attention to the ongoing CD reissue campaign, he retitled one of the uncompleted Berlin outtakes after her. The Eastern-inflected “Abdul majid” would appear among the bonus tracks on the “Heroes” rerelease.

Iman’s modeling career had been launched during her time at the University of Nairobi in Kenya, where she studied political science. Walking to class one day in March 1975, she was spotted by photographer Peter Beard. Beard was with Kamante Gatura, who had once been Isak Dinesen’s cook and was immortalized in her novel Out of Africa. The pair were on their way to have lunch when Beard spotted “this amazing Somali girl . . . striding down [Standard Street]. So we parked our Land Rover and went into the New Stanley Hotel, and who should be walking into the New Stanley? I went up to her and said ‘I hope you’re not going to let all those aesthetics go to waste. Don’t you think we should just record some of it on film?’”

Bowie and Iman in November 1990. Bowie said the moment he first saw her, “I was already naming our children.” (© RON ALELLA/WIREIMAGE.COM)

According to legend, Iman agreed to pose only if Beard agreed to finance her college tuition. He accepted and, some 600 photographs later, he traveled back to the U.S. to launch Iman on the modeling world — by introducing her as a poverty-stricken, nomadic goat herder whom he’d stumbled upon in the bush, the Northern Frontier District which lies between Kenya and Somalia.

It was an incredible story, and a total fabrication. The daughter of a Somali diplomat, the second of five children (she has two brothers and two sisters), she was educated at boarding schools in Somalia and Egypt. Her father’s work saw her spend some time living in Saudi Arabia before the family uprooted and moved to Kenya following the Somali revolution in 1969.

Beard’s fable worked nonetheless, capturing the imagination of everybody who heard it, and, even before Iman arrived in the United States to join the internationally renowned Wilhelmina Models agency, the celebrity pages were drooling for her, waltzing her past all the traditional stages in a model’s rise to fame, and establishing her as a superstar overnight.

By the end of 1975, Iman was one of the highest-paid models in the world. Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren and Bill Blass lined up for her services, while any color boundaries that had hitherto existed in the fashion world came tumbling down. The first black woman to feature on the cover of French Vogue, she was also the first to be given a contract by a major cosmetics company (Revlon). When she married probasketball player Spencer Haywood in 1978, the wedding was ranked among the celebrity bashes of the year.

Iman moved tentatively into acting. She had small parts in the movie Out of Africa, and in TV’s Miami Vice and The Cosby Show. However, a serious road accident in 1983, when the taxicab in which she was a passenger was involved in a collision, saw her career begin to crumble. Besides a dislocated shoulder, three broken ribs and a broken collarbone, her cheekbones (the attribute that first attracted Beard, and which were now as renowned as any single body part could be) were shattered.

She recovered, but her life, it seemed, couldn’t. Her marriage broke up in 1987, and the world of modeling had, naturally, moved on. So did Iman, into the world of business, and, now, into the arms of David Bowie. There began what so many commentators have since described as an “old-fashioned” courtship, although it might be more accurate to describe it, simply, as a beautiful one. Within four months of meeting, the pair had moved in together; but both before and after that, on the 14th of every month, Bowie marked the anniversary of their meeting by having a bouquet of flowers delivered to her, no matter where in the world she might be.

In December 1990, carefully worded statements from both Bowie and EMI announced that, after seven years, their partnership had ended, and that Bowie was now, once again, a free agent.

It was not difficult to read between the lines. Bowie had been chaffing at the EMI contract for several years now. For his closest associates, it was difficult to shake the belief that it was the terms of the contract, not creative bankruptcy, that was responsible for the last couple of bad David Bowie records, and that it was a determination to get out of it that was responsible for the last decent one. Few people ever said as much, but when your record company is desperately hoping for the next Let’s Dance, Tin Machine was scarcely guaranteed to bring a smile to the corporate face.

Neither was Tin Machine II. The group’s second album had lain more or less complete for a year now, without any sign of release. Indeed, so far as EMI was concerned, the fact that Bowie’s back catalog was performing so well only exacerbated Tin Machine’s failings. While the ChangesBowie hits collection topped the UK chart, all seven of the old albums reissued had made some kind of showing, with 1972’s Ziggy Stardust even reaching the Top 30. And how was Bowie intending to follow through? With another impenetrable roar of pseudonymous garage noise. Well, he could follow it through with another record company, assuming he could even find one. For the first time since his relations with Decca Records dissolved back in 1968, following the unsuccessful release of his very first LP, David Bowie found himself without a record deal.

The next few months of 1991 were spent trying, increasingly desperately, to negotiate a new contract, with the tapes of the second Tin Machine album as the less than alluring bait. Basing himself in Los Angeles, Bowie was almost reduced to trudging from office to office, his increasingly shelf-worn master tape tucked under one raincoated arm — he also found time to appear in the second season opener of Jon Landis’ HBO TV comedy, Dream On, mugging his way charmingly through the role of crusty British film director Sir Roland Moorcock.

But there was a growing sense of unease in the air, one that Bowie himself is said to have expressed, at the L.A. Roxy in early February.

Playing Manchester, England, during the Sound + Vision tour the previous summer, Bowie was introduced to Morrissey, a singer who had first emerged in the early 1980s fronting a frightfully earnest and clumsy band called the Smiths, but who had since shrugged away the adolescent trappings of that band to launch a solo career that was as luminescent as the Smiths was turgid (though their devoted fans would deny it vociferously).

Predictably, the media was quick to dub Morrissey the latest in that seemingly inexhaustible line of “new David Bowies,” an honor that the singer himself seemed more amused than impressed by. But he was a die-hard Bowie fan all the same; as a fourteen-year-old Ziggy fan, catching Bowie at the Hard Rock Theatre in 1972, Morrissey had wrapped a twopence piece in a piece of paper with his phone number written on it, and pushed it through the window of Bowie’s Daimler.

The singer never called him but, eighteen years later, he would happily confer some form of approval upon his young disciple. “He’s an excellent lyric writer, one of the better lyric writers that England — and it’s very English — has produced over the last few years. I like the records . . . I’ve never seen him live.”

Now that was to change. Backstage at the L.A. Roxy, Bowie readily agreed to join Morrissey onstage, running out to duet through the singer’s then-customary encore version of Marc Bolan’s “Cosmic Dancer.” But he also answered a few fans’ questions as he lingered around the Roxy, including a telling response when he was asked about his own plans. “Plans?” he laughed. “I don’t even have a fucking record label at the moment.”

It would be March 1991 before anybody finally bit. That month, it was announced that Bowie had signed with Victory Music, a newly launched subsidiary of the JVC electronics company with worldwide distribution through Polygram. It was a less than convincing partnership. New labels came and went at an alarming rate in the early 1990s, and little about Victory suggested it was any more likely to last the course than any of the others.

Even more incredibly, this deal was apparently dependent upon Tin Machine spicing up the existing tapes with a few more commercial songs, a demand that sent the band scurrying back to the studio that same month to record the newly penned “One Shot” with producer Hugh Padgham, coproducer of Bowie’s Tonight album, and the ears behind a clutch of Phil Collins and Sting megahits.

Nice jacket, shame about the guitar. Or vice versa? Broadcasting the Paris Moscou Show, 1991. (© PHILIPPE AULIAC)

The technological innovations for which Padgham was best known (the percussive fission that propelled Peter Gabriel’s “Intruder” and Phil Collins “In the Air Tonight,” and had flavored the best of his work ever since) were not to be called upon here. Although Padgham readily admitted that “One Shot” was “a bloody great song,” his excitement at working once more with Bowie was tempered by the metallic roar with which the band intended draping the number.

Yet even he had to concede that Tin Machine appeared to know what they were doing. The year or so since the release of Tin Machine had seen the secret break wide open. Bowie’s beloved Pixies had scored no less than five British hit singles, including the classics “Monkey Gone to Heaven” and “Here Comes Your Man,” and the Top 30 smash “Planet of Sound.” New York noise merchants Sonic Youth had signed with the major label Geffen and released the mainstream-munching Goo; now Geffen had just picked up Nirvana and were confidently predicting quarter-million sales for that band’s next album, Nevermind.

Across the U.S., audiences were delving and stage-diving into precisely the kind of blistered, brutal hard rock sound that Tin Machine alone had hitherto waved in the face of a large-scale audience. And that enthusiasm was only going to grow louder, once Nevermind was released, and once Geffen shipped that anticipated 250,000 in a matter of hours. Grunge Rock was coming, and Tin Machine not only knew it, they were signposting it. And the only people who didn’t understand that were, sadly, those who were most likely to appreciate what they were doing.

No matter how valiantly Bowie fought against it, the bulk of Tin Machine’s marketing was aimed at the audience he was traditionally sold to. Nobody, neither EMI nor Victory, ever dreamed of trying to push Tin Machine to the college crowd, to the flannel-and-boots kids, to the great unwashed mass that lurked in dying mill cities and dilapidated lumber towns, and when Bowie himself raised that possibility in print, readers and writers alike simply shrugged and assumed he was just trying to sound hip. In fact, as the (admittedly limited) best of Tin Machine II proved, he was being as honest as he ever had been.

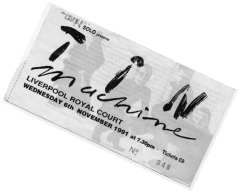

Rehearsals for Tin Machine’s next tour got underway in July 1991, first in St. Malo, France, then in Dublin, Ireland. Unlike the mere guerrilla raid to which they had treated the world last time around, this was to be a full-blown assault, a sixty-nine-date outing that would take the band across twelve countries and last for close to five months. It was a daunting undertaking.

Again, the group swore off performing any Bowie composition that predated their own formation. But far from resigning themselves to disappointing audiences, the group only viewed it as a challenge; the knowledge that they would have to work to impress the crowds that faced them, and could not afford to cruise for a moment. Indeed, no matter how grueling the scheduled tour might be, the band only added to their workload by interrupting the rehearsals for a handful of impromptu shows around the Irish capital, and a couple of UK TV appearances: the comedy show Paramount City and, most ill-advisedly, Irish chat show host Terry Wogan’s eponymous yack-fest.

It should have been an easy enough assignment. Compared to some of the pit bulls who front that sort of show, Wogan was a genial enough host. But he expected a degree of decorum from his guests in return, and the sight of Reeves Gabrels playing bottle-neck guitar with a vibrator during the show’s musical interlude, was too great a transgression. By the time Bowie returned to his seat, Wogan was livid. How dare these people bring sex toys onto his show?

“David, have you seen my deckchair anywhere?” Tin Machine at the Glasgow Barrowlands, 1991. (© DAVID NEISH)

On the other side of the Atlantic penises had already caused Tin Machine a fair degree of bother. Proving that he was not afraid to revisit his past when he felt the urge, Bowie approached Edward Bell to design the cover art, a decade after the artist delivered the eye-catching cover to Scary Monsters.

Back then, Bell had drawn upon a succession of Bowie’s own past and present images to produce a fascinating sketched collage that effortlessly summed up the album’s stylistically scattered contents. This time around, he chose to work with a more singular image, a charcoal sketch of a Greek kouri, a statue dating from the 6th century BC that represented the idealized image of man, a perfect physique, but with no individual identity.

Four were lined up alongside one another, with just one — visible on the reverse of the cover — readily discernable as a band member (Hunt Sales’ “It’s my life” tattoo, which stretches right across his back, was hard to ignore!). It was a stark, spartan design, but it was also engineered for maximum impact, as Bell retained the Greeks’ penchant for realism, and equipped each of the quartet with genitals. No big deal. You can see the same thing in a museum any day of the week. But record stores aren’t museums, American record stores in particular. Alone in the western world, Victory’s U.S. division took one look at the sleeve and reached for the fig leaves.

The response was not altogether surprising. Most modern chronicles consider the mid-1980s to be the point when overt censorship first raised its head in the U.S. music industry, notably with the advent of the Parental Advisory warning stickers, but nudity had never been tolerated on record sleeves. In 1969, a John Lennon and Yoko Ono album was physically repackaged in a brown paper bag to prevent the young newlyweds’ nude embrace from offending passersby; and, twenty years later, a painting of Perry Farrell’s penis was airbrushed from the latest Jane’s Addiction CD, Strays.

So it was with Tin Machine II. No matter that one could walk across the border into Canada and pick up all the Tin Machine todgers (to use a British expression) you wanted. The United States remained a willy-free zone, and it was astonishing just how much of the album’s eventual press coverage would obsess not on the guitars, drums and bass, but on the organ alone.

Tin Machine themselves played along with the ensuing debate. “When you look at something like that, and you realize it’s art, what’s the problem?” asked Gabrels. “You know, either you got a dick or you don’t. Everyone’s got some sort of genitalia, and it’s no surprise. It’s an accepted work of art. [And] when you talk to people, you know average people, it’s like ‘hey yes, I don’t have no problem with that, why did they do that, that’s silly.’”

Average people probably didn’t have problems with vibrators, either. After all, it’s not as though they’re real penises, is it?

Back on Wogan, however, the host was having none of that. “I suppose that’s not a real guitar either,” he snapped.

“No, it’s my lunch,” Bowie replied, and Wogan later told readers of his autobiography that Bowie never realized how close he came to being “slapped.” Now that would have been good television.

The vibrator would not sit still. Ten days later, back in Los Angeles, Tin Machine marked the official opening of their tour with a specially convened show at lax airport, playing beneath the roar of the jet planes, and turning in an altogether alluring performance for the watching ABC In Concert cameras. But then one of the show’s crew caught sight of the vibrator . . . two of the things, in fact . . . dangling in readiness from Gabrels’ mike stand, and all hell broke loose.

Gabrels tried to explain the need for such things. “You Belong in Rock ’N’ Roll,” he said, was “basically [a] bass song, and I wanted to try to lay in some industrial stuff against it. I started with my electric razor . . . [but] I wanted something with a variable speed so I could tune it to the track, and . . . my guitar tech said a vibrator. So we went and got some.

“You can . . . use them as a sound source, and also as a string driver by laying it against the bridge, because you get that really fast vibration which bounces against the strings and makes the string vibrate, which is how you produce sound anyway. So it works as a string driver. I actually get to do a vibrating string solo at the end of ‘You Belong in Rock ’N’ Roll,’ which is cool.”

But it was also too much for American television. Dangling from the microphone, the surrogate sex-thing was fine. But the moment he took it in his hand . . . “They ended up not showing the song that I used the vibrator in. It was like it wasn’t obscene when it’s just hanging there like that, but when I picked it up and used it, when the camera came in for a closeup, it became obscene. It’s like as soon as you use it to play a chord, it’s obscene.”

Obscene or not, “You Belong in Rock ’N’ Roll” became Tin Machine’s first single that summer, with the tour kicking off around the same time, and this was true despite the fact that Tin Machine II was still several weeks off, a void that left audiences utterly unprepared for exactly what they might find within, then left them gasping once they did hear what the band had in store.

The first reviews of Tin Machine II were harsh; even the good ones were hesitant. Most people acknowledged a clutch of good songs, a couple even singled out one or two great ones. But not one could pass by without mentioning what remains positively the worst song ever to appear on a David Bowie album.

He’d come out with some genuine clinkers in the past, of course. Bowie’s affection for “Ricochet” notwithstanding, was there any worse moment on Let’s Dance than that? (Actually, yes — “Without You” was pretty lackluster as well). The Labyrinth soundtrack labors beneath some appalling missteps, and most of Tonight was disposable.

But “Stateside” outdid them all, a rambling Hunt Sales cowrite and vocal that seemingly lined up every rock ’n’ roll cliché of the past forty years and crammed them all into one six-minute nightmare. And if it was horrifying on vinyl, it was even worse live, as the drummer vaulted over his kit to drag the audience Stateside with him, an experience that occasionally lasted eight, nine, even ten minutes. No matter what else Tin Machine pulled out of the hat as the tour rolled on, “Stateside” would inveigle itself into every watcher’s consciousness, and scar the memory forever. Even Bowie occasionally looked uncomfortable.

Contrasting the sharp, gangster uniformity of the first tour, this time around Tin Machine was a blaze of color, Bowie resplendent in some of the most scarily hued trousers he had worn in a long time (the black-and-yellow stripes made him look like a very tall wasp); Hunt Sales’ shorn, bleached hair giving him the look of a debauched George Washington.

Tin Machine in London, 1991 — a great band in search of a better wardrobe. (© BIANCA DIETRICH)

There was also a new face onstage with them, rhythm guitarist Eric Schermerhorn. Destined later in the decade for stints with Iggy Pop (the American Caesar album), They Might Be Giants and Mono Puff, Boston-based Schermerhorn was a past member of such Massachusetts mini-stars as Ooh Ah Ah (who once had a demo produced by The Cars’ Dave Robinson) and Adventure Set (runners-up in the city’s 1985 Rumble). Gabrels, who remembered him from his own days in Beantown, recommended him to the band, and it proved one of the best ideas he ever brought to Tin Machine.

Filling in around and behind Gabrels’ lead work, Schermerhorn was very much the unsung hero of the Tin Machine show, a rock-solid anchorage around which his bandmates’ improvisational flurries could not help but orbit. Certainly, as one sits through the live footage shot (for eventual home video release) at Hamburg’s Docks club, Schermerhorn’s calm offers a much-needed corollary to the sometimes scintillating (but often, simply grueling) extravagances taking place elsewhere on the stage.

Schermerhorn was not, however, the only powerful influence on the road that fall. Iman Abdulmajid, too, was traveling with the group — or, at least, with Bowie, and it was in Paris at the end of October 1991 that he proposed marriage to her. He chartered a boat trip down the Seine, hired a musician to perform the decidedly unseasonal “April in Paris,” then fell to his knees beneath the Pont Neuf bridge to sing a refrain of “October in Paris,” and pop the question.

“She was shocked,” he admitted later. “But she didn’t hesitate for a second.”

The European leg of the tour ended in Bowie’s birthplace of Brixton, London, on November 11. It was there that a flying packet of cigarettes, hurtling out of an audience that, over the past few months, had taken to bombarding the chain-smoking Bowie with such gifts, caught the singer in the eye.

It was a solid blow. He actually left the stage to have it attended to, but returned a few minutes later to take full advantage of the moment; for the first time since 1974, when a bout of conjunctivitis forced him to perform “Rebel Rebel” in glam swashbuckler drag, Bowie reappeared on stage with an eyepatch — the ideal garb for what had become one of the highlights of the Tin Machine live set, that snarling version of “Shaking All Over.”

Four days later, the band was opening its U.S. account at Philadelphia’s Tower Theater (the same venue where Bowie had recorded his David Live album in 1974). The band was now tighter than it had ever been before. Their appearance on TV’S Saturday Night Live a few weeks later was one of the most exciting performances seen on American television all year. Behind the scenes, however, both Bowie and Gabrels were feeling strains that they could never have imagined when they had initiated the Tin Machine project three years before.

Off-duty in Hamburg. (© BIANCA DIETRICH)

The group had never made any secret of its love for what one might euphemistically term the “rock ’n’ roll lifestyle,” although Bowie and Gabrels, at least, paid only token attention to even its rudiments — the “Fuck you, I’m in Tin Machine” T-shirt that was one of Bowie’s favorite outfits, for example. The teetotaling Tony Sales, too, steered clear of the damaging excesses that his chosen career threw his way. But still, drugs made their way into the band’s inner sanctum, and Bowie, in particular, found it difficult to deal with. He later admitted, in fact, that “that really destroyed the band, more than anything else. It got to a situation where it was just intolerable. We just couldn’t cope.”

Half expecting every day to wake up and find a corpse on the tour bus; dreading the moods and attitudes that can sometimes accompany someone through what they perceive to be “a really good time,” Bowie battled through the last weeks of the American tour, finally coming to rest in Vancouver, Canada a few days before Christmas.

The last few shows were difficult, anyway. Climbing up the I-5 corridor from San Francisco, motoring into Seattle as it celebrated Nirvana’s ascension to Rock Godhood, Tin Machine suddenly became aware of just how irrelevant they were.

Rock had undergone its little cultural convolutions in the past, and, no doubt, would undergo more in the future. But it is rare that one finds oneself bright-eyed and bushy-tailed in the very heart of one, at the precise moment when base metal is transformed into gold. From the moment the band washed up at Seattle’s Paramount Theatre, that gold glittered everywhere: in the local radio’s nonstop diet of Pacific Northwest grunge; in the local stores’ window displays of lumberjack shirts and ready-torn denims; and in the empty seats that stared out of a show that had sold out several weeks ahead of time. It was as though the entire city had suddenly remembered it had something else to do that Christmas, and it went off to do it. “I saw Tin Machine play eight times that tour,” one fan recalls, “and Seattle was the worst show I’ve ever been to.”

A lot of musicians have pinpointed fall 1991, and the release of Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” as the moment when everything changed for them. Robyn Hitchcock once laughed, “it all became ‘rock’ again, people were allowed to have long hair and punch the air again, buy pretzels and shout ‘way to go.’”

More crucially, however, it was suddenly important to be young again. For years, the rock hierarchy had been aging (gracefully or otherwise), until even the hottest and hippest “alternative rock” bands, the likes of the Cure, REM, U2 (and Hitchcock himself), had been knocking around for a decade or more, and their omnipresence had formed a barricade that no amount of youthful sweating and straining could dismantle. Now, the very brickwork was shattered, and suddenly all the attributes that had once seemed assets — experience and familiarity paramount among them — were howling liabilities. An entire way of musical life was shattered, and few of the ensuing casualties would ever be the same again.

For Tin Machine, however, the blow was harder than that. It was as though they’d been transformed from pioneers to plagiarists in the time it took to play one single and, although a month-long break for Christmas and the new year allowed the band a little time in which to reacclimatize, it was obvious that, no matter where they went, they would only ever be trailing in the footsteps of the Grunge that had gone before them.

Hairstyles may come and go, but an old hat will never let you down — Munich 1991, still wearing the Man Who Fell To Earth’s favorite headgear. (© BIANCA DIETRICH)

Into the new year, 1992, the band continued on through a two-week Japanese stint. But no sooner had they played their final scheduled show in Tokyo on February 17, than the quartet parted for the final time.

The break was not, Bowie insisted, a permanent one. There would be a new Tin Machine album in a year or so, with a live record in between times. But still there was a sense of finality to the farewells to match the futility that had haunted the group’s last few months together, as Bowie finally came around to Gabrels’ thinking, that the time for Tin Machine had ended after the first album.

Even with the benefit of the lashings of hindsight, a healthy taste for irony and all the forgiveness in the world, Tin Machine’s 1991 tour lives on in the mind as the flaccid flailings of a good idea grown old; and, even with one finger on the fast forward button, the live video and album are extraordinarily difficult to get through.

“Once I had done Tin Machine, nobody could see me anymore,” Bowie reflected. “They didn’t know who the hell I was, which was the best thing that ever happened, because I was back using all the artistic pieces that I needed to survive, and I was imbuing myself with the passion that I had in the late 1970s.”

He was correct. Indeed, although he never truly echoed Gabrels’ dramatic assertion that Tin Machine had fallen on the hand grenade that was Bowie’s career after Let’s Dance, the point was made regardless. From the moment that album hit, after all, Bowie was viewed not as an artist but as a moneymaker, a hit machine, and he had fallen for that same shtick himself. Tin Machine scrapped that notion and returned Bowie not, perhaps, to year zero, but at least to the same shadowy roost from which he had originally contemplated the 1970s. And, just as his The Man Who Sold the World album had obliterated memories of “Space Oddity,” and permitted him to rebuild from a point beyond the point of no return, so the similarly abrasive Tin Machine washed away the sins of Tonight and Labyrinth.

Bowie was his own man again. Now all he needed to do was find out for himself who that man might be, and, while he searched, he could spend time with Iman, plan for their wedding, enjoy some domesticity, and maybe think about getting his own solo career back on track. “A small room packed with people is a cool thing, but it’s not economical,” Bowie mused. “I was paying for that band to work, and I was gradually going through all my bread and it became time to stop.”