Of all the outside impetuses that Bowie and (to a lesser extent) Eno brought to bear on their new music, the most pronounced was the edgy experimental thrust of the Industrial scene that had developed on the fringes of the (primarily) American underground over the previous five years, whose most powerful adherents described Bowie as a primary influence upon their own muse.

Industrial music had long since become established as the soundtrack to the artistic endeavors that Bowie so admired. If you’re going to bang iron nails through your hand, what better accompaniment could there be than a wall of guitars banging sonic nails through your head? And, though that might be a glib summary, it was one that became very real to a lot of people as the 1990s progressed, Bowie among them.

A musical force that was destined to become one of the most readily identified and most misunderstood forms in modern rock history, “Industrial” lurked within a range of sonic expressions that could range (and rage) from the clattering pop of Depeche Mode’s “People Are People,” to the impenetrable buzz of the noise-art experiments of Pre mature Ejaculation; from the harsh “aggro” of Ministry, to the dense swamps of Current 93, and on through a sprawling army of electronic and percussive auteurs and mavericks who worked so far left of musical center that even their melodies rejected conventional mores.

It was the British band Throbbing Gristle who first formulated an “Industrial” sound, during 1977 and 1978. “When we finished [our] first record,” front man Genesis POrridge said, “we went outside and we suddenly heard trains going past and little workshops under the railway arches and the lathes going and electric saws and we suddenly thought, ‘we haven’t actually created anything at all, we’ve just taken it in subconsciously and re-created it.’”

Captured looking casual in London, 1995. (© BIANCA DIETRICH)

The theory behind the late seventies genesis of Industrial revolved around taking risks, and then taking them as far as they would go. Too far, complained some observers. Even P-Orridge was once moved to muse, “Sometimes I think we’ve given birth to a monster, uncontrollable, thrashing, spewing forth mentions of Auschwitz for no reason.” But he was also aware that, “up until then, the music had been . . . based on the blues and slavery. We thought it was time to update it to at least Victorian times, the Industrial Revolution.”

It was the emergence (and subsequent arrival on British shores) of the German groups DAF, SPK and Einstürzende Neubauten; of Australian Jim Thirwell’s manifold Foetus variations; and the Californian Boyd Rice which gave Throbbing Gristle’s hitherto exclusive scene its first outside impetus, and empowered others to maintain the momentum. All took their power not from chords and choruses but from pure sound, with the German contingent adopting the pure sonics of a hammering metalworker, the pounding of the construction site, the roaring of engines.

The ensuing soundscapes frequently defied even the most liberal interpretation of “music,” but would become an integral part of it nonetheless. As early as 1982, Germany’s Die Krupps took the first steps toward hybridization, as their “Stahlwerk symphony” single juxtaposed factory sounds with experimental keyboard melodies. Two years later, Depeche Mode were rewiring a studio Synclavier to regurgitate not the instrument’s own preprogrammed sounds and effects, but a string of soundtracks far removed from anything hitherto applied to a “simple” pop record.

Depeche Mode’s Martin L. Gore was one of the witnesses to Einstürzende Neubauten’s first ever UK show, a self-explanatory Metal Concerto, staged at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts in early 1983. “The power and excitement of it was brilliant,” he said afterward. Already he was contemplating how to use “the ideas in a different context, in the context of pop.” The result, the singles “People Are People” and “Master and Servant,” remain mile stones in the development not just of Industrial music through the 1980s, but of rock and pop in general.

“Every band has to start taking risks to progress, [although] it’s pretty much in the lap of the gods whether [anyone] will understand the changes,” mused Nitzer Ebb’s Bon Harris in 1990. Seven years earlier, Depeche Mode had taken that same belief further than any band in their position ever had before.

Industrial’s natural boundaries became increasingly blurred in Depeche Mode’s wake. Both the modern dance and decades-old Progressive Rock scenes were hijacked and used as influences, Eno’s mid-1970s ambient albums and Bowie’s Berlin trilogy became eternal flagships, while Heavy Metal became an inalienable element in the brew as guitars made a loud and shatteringly distorted comeback.

The search, after all, was not for “fashionable” music, but for confrontational sound, an evolution that climaxed in the early 1990s with the commercial breakthroughs (in swift succession) of Ministry, Skinny Puppy and Trent Reznor’s Nine Inch Nails, bands whose forthright nihilism found a symbiotic echo in the same tides of ritualistic chaos and despair that Bowie was so intent on isolating in his own music.

He would never have been so crass as to attempt to make an “Industrial” record; the linkage that he sought and encouraged was spiritual, not musical. True, keen ears would soon be drawing parallels aplenty between Bowie’s latest strivings, and the flavors flowing elsewhere, but it was the tightly coiled Reznor and his own, oft-confessed debt to Low that most intrigued Bowie.

Since his emergence in 1989, across the course of two albums (Pretty Hate Machine and The Downward Spiral) and an album-length EP (Broken), Reznor had exerted an astonishing influence upon the mainstream American imagination, at the same time as his own brand of bleak electronica was set to induce the mewlings of a brand new generation of wannabe nihilists.

Sequestered in the house on Cielo Drive, Los Angeles, where he recorded The Downward Spiral (and where, in 1969, the Manson gang murdered Sharon Tate and her friends), Reznor listened to Low at least once every day, reveling in its “emotional content, that feeling of coldness and desperation, and the daring of the song structure.” Bowie, he explained, “has this ability to push himself, which is part of an artist’s job.” Projecting his own career twenty, thirty years into the future, Reznor said, “When I get to the stage he’s at, if I get there . . . I hope . . . that I do it with the same class and optimism.” For now, his love of Bowie simply inspired him to invite Adrian Belew to guest on the album. He was completely unaware that Bowie himself was drawing at least some inspiration from Reznor’s work.

One of the great disadvantages of recording, Bowie had learned long ago, was the ease with which one became isolated from all that was going on in the larger musical world. He overcame this by purposefully setting time aside to pick up and play through as many recently lauded new releases as he could bear, discarding those that didn’t grip him within their opening minute or three, then persevering with the remainder.

Nine Inch Nails were one of the precious few acts that passed this test (the Dust Brothers were another). But, although the sounds of the Industrial revolution would certainly make themselves felt in Bowie’s music, for any commentator to linger upon them was to overlook a lot of other, equally left-field moods and notions that were running through the gestating project: the reliance on improvisation; the spectacular spontaneity that burned around an otherwise conventional song structure; the lyrics that chopped and changed direction without ever losing their plot; and, towering over all, Bowie’s decision, after so many years of threats, to unleash a full-scale “concept” album, one that wouldn’t simply hang on a narrative thread but would exist purely to propel that concept along.

In his mind, the fictional community of Oxford Town sprang fully formed from his own enjoyment of David Lynch’s ultra-creepy TV series Twin Peaks; and, with it a cast of characters that could, if anything, outdo any of Lynch’s own: the detective Nathan Adler, the murdered Baby Grace, the priestess Romano A. Stone, the informant Paddy, the dead artist Rothko and the dealer Algeria Touchshriek, all cast together in a nightmare tangle of body-part jewelers, DNA prints, art-ritual murders and Orwellian thoughtcrimes.

Bowie had visited such scenarios in the past. The Hunger City scenario that kick-started Diamond Dogs’ trawl through a grim future, the hollow marketplace in which “Five Years” unfolded, the ravenous television screen of “TVC 15,” all moved through the shadows that draped Oxford Town, ideas and ideals that could “surf on the chaos” that Bowie believed modern life had become. “There are strong smatterings of Diamond Dogs in this album,” he confessed. “The idea of this postapocalyptic situation is there, somehow. You can kind of feel it.” He also acknowledged that the roots of that particular album, his own fascination with George Orwell’s 1984, had become “transferred” into this latest creation. “This kind of updates it.”

Once, years before, Bowie was asked how much longer he thought the human race had left. He replied that it was already doomed. Now he looked to reinforce his prediction. “There’s [no longer any] point in pretending, ‘well, if we wait long enough, everything will return to what it used to be like, and it’ll all be saner again, and we’ll understand everything and it’ll be obvious what’s wrong and what’s right.’ It’s not gonna be like that.” Instead, it would be like this, and he pointed to the gestating new album, via the “occasionally ongoing short story” he presented to Q magazine in December 1994: The Diary of Nathan Adler, or the Art-Ritual Murder of Baby Grace Belew.

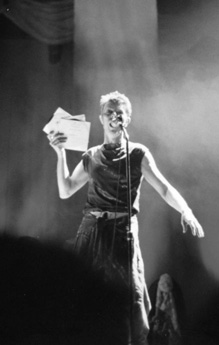

Sheffield, 1995. Bowie’s Outside tour was every bit as conceptual as the album itself. (© GRAHAM MCDOUGALL)

Darkly fragmented, deliberately disturbing and disgustingly graphic, the three-page story essentially laid out the framework for what Bowie and Eno now determined would be a three-hour song cycle entitled Leon. But still the record companies shuffled their feet and mumbled about shifting units. Even in the age of CDS, the triple-disc release that Bowie was demanding was way too expensive a proposition for them to consider. As 1995 dawned, it became apparent to everybody involved that their dreams of Leon being released as it was originally envisaged, “uncompromised” (as Gabrels said) “by financial/commercial pressures,” was doomed.

Bowie offered to trim down to a double. Again, no go. Finally, he caved in, agreeing to render Leon as a mere single disc, and, to sweeten the pill even further, he would replace some of the more impressionistic passages with a few straightforward (at least by comparative standards) numbers. His one condition lay in reserving the option to maintain the saga over a slew of forthcoming releases. At one point, Bowie was intending for Leon to consume his next five years’ worth of albums, all leading up to one final millennial blowout, a piece of “epic theater” to usher in the year 2000.

In the meantime, he had a record to finish. In January 1995, Bowie booked into the Hit Factory in New York and began collecting fresh faces around the already in situ nucleus of Eno, Gabrels and Garson: Carlos Alomar returned to his side for the first time since the Glass Spider was laid to rest, the eternal Kevin Armstrong, engineer David Richards and drummers Joey Barron and Sterling Campbell.

The change of scenery and approach was not entirely undertaken for commercial purposes. Early on in the month, Eno admitted that much of what they’d already accomplished sounded “rambling, murky, over-and-over-dubbed. All very undisciplined in my opinion.”

Throughout the earlier sessions, he fought against Bowie’s decision to record on forty-eight tracks, arguing that the more room one had on the tape, the more unnecessary frills could be retained. “Things [were] just left where they happened to fall,” he told his diary. In Eno’s opinion, they needed to start picking them up again, even before Bowie was persuaded of the need to layer in some more commercial material. Still, many of the album’s most popular cuts emerged from these sessions.

The grinding “We Prick You” developed out of a drum pattern laid down for another song entirely — although Eno was pleased with this, he was never going to be happy with Bowie’s original idea for the chorus, “we fuck you, we fuck you.” There was a reworking of The Buddha of Suburbia’s “Strangers When We Meet”; and an astonishing revamp of a cast-off from Tin Machine’s second album, “Now,” which ultimately became the new record’s title track “Outside.”

Best, perhaps, of all Bowie’s musical efforts in so long one gives up trying to count, however, was “Hallo Spaceboy,” a number that came hurtling out of an instrumental Gabrels demo called “Moondust.” Positively the most apocalyptic number Bowie had composed since the days of Diamond Dogs, it was also one of the most calculated, its soundtrack delving into the heart of the burgeoning Industrial music sound, as intelligently as “Rebel Rebel” summarized glam rock. Neither was that comparison to pass Bowie himself by. The lyric is defiantly cast in a similar mold to that earlier rabble-rouser (and, as if to complete the thematic triumvirate, would resurface a few years later in “The Pretty Things Are Going to Hell”).

Again, the sessions danced on the brink of improvisation. “Hallo Spaceboy” is one of the numbers that Eno later said were “stripped down to almost nothing [before] I wrote some lightning chords and spaces and suddenly, miraculously, we had something.”

Lyrically, too, Bowie was taking chances once again. A San Francisco–based computer-savvy friend had recently joined Bowie in developing what they would later christen the Verbasizer, a program that allowed him, he said, “to take a sentence [from a newspaper, a book or elsewhere], divide it up into columns, and set it to randomize, so what you end up with is a kaleidoscope of nouns, verbs and words, all slamming into one another.” The results, he said, then allowed his own mind to travel toward concepts and imagery he might never have thought of unaided, flashing new situations and scenarios out from which he could extrapolate.

“I Have Not Been to Oxford Town” was one early beneficiary of this new freedom. The basic track was put together by Eno, Alomar and Barron, but only came to life after Bowie heard it for the first time and began frantically scribbling a lyric. Then, the moment he was finished, he went into the vocal booth and, according to Eno, “sang the most obscure thing imaginable. Within half an hour he’d substantially finished what may be the most infectious song we’ve ever written together.”

Indeed, once it was all over, Eno’s sole complaint was that much of the music was more cluttered than he would have preferred. “The only thing missing was the nerve to be very simple.” Too many of the final mixes, particularly once the New York material was introduced, hit the listener somewhere between the groin and the jugular. But Bowie reminded him that that was the point. Eno, Bowie laughed, is “a lot more fearful of testosterone than I am. I love it when it rocks. I love it when it has big, hairy balls on it. Layer it on, the thicker the better!”

Well, one is tempted to ask, why didn’t you do that in the first place?

The strictures under which the album was now being made resulted in some ruthless trimming; by the time the sessions wrapped up, more than twenty-five hours of discarded material lay on the cutting room floor, so much of it that Bowie even mused on the possibility of releasing “a companion piece, a sort of archival limited-edition album,” if only he could bring himself to start listening to it. “It’s just so daunting,” he shuddered eight years later. “We did improv for eight days [and] I just cannot begin to get close to listening to [it]. But there are some absolute gems in there.”

Even with all the chops and changes, however, there was a moment of nervousness in April when it suddenly seemed plausible that the entire project would need to be scrapped. No fewer than thirteen years after his last album, Scott Walker was stirring once again, and the first anybody knew about it was when his name, and the title Tilt, appeared on the New Release sheets, just weeks ahead of the album itself. Bowie’s heart sank when he heard about that.

The reasons for his fears were plain. Since reimmersing himself in Walker’s work via Black Tie White Noise’s take on “Nite Flights,” Bowie had very much aligned his musical ideas with the same starkly nonlinear notions that had pushed Walker toward Climate of Hunter.

Of course, Bowie’s aesthetic pushed beyond even those notions. Early on in the Montreaux sessions, Bowie was wondering where Walker could possibly have gone from that album, and suggesting that Leon posit one possible direction (or words to that effect). Now Walker himself was preparing to answer that question with a record whose earliest reviews could easily have been applied to Bowie’s initial efforts: “funereal, operatic, monumental,” warned Alternative Press, “Tilt is the album too many people have promised to make, but none could ever deliver. Pretentious, preposterous, angular songs with a monster around every corner . . . what Walker himself was thinking as he prepared this slab of unrelenting darkness for release is as imponderable as the music itself.”

Eno certainly understood the ramifications of the forthcoming release. “Scott Walker’s record could occupy much of the territory of Bowie’s,” he mused, and he was under no illusions of what would happen if that became the case. A year of work down the drain. “Bowie won’t release those things, and, as time passes, more will get chipped away or submerged under later additions.” It was with some relief, then, that he took a call from Bowie at the end of April saying that the panic was over. Bowie had received a copy of Tilt, and he played one track over the phone to Eno. It was as spectacular as they’d expected. But it sounded nothing like Leon.

Performing “DJ”; during the tour, Bowie would hold a handful of record singles and toss them over his shoulder, like in the original video for the song. (© GRAHAM MCDOUGALL)

And finally, the waiting, the nervousness and the uncertainty was over. In May 1995, Virgin Records stepped forward with an offer for the album’s American release (Bowie remained with Savage’s distributors, BMG, in the UK). Bowie accepted it. The newly retitled 1.Outside would be released worldwide in September. And now it was the world’s turn to wait.

The packaging was extravagant. One of Bowie’s own paintings, an appropriate self-portrait, Head of DB, was wrapped around a voluminous booklet, the diary of the character Nathan Adler. Then you put the disc in the player and, two largely instrumental minutes later, Bowie spoke for the first time. “Not tomorrow,” he yowled. “It happens today.” And was it churlish to emerge eighty minutes later to admit that “surprisingly, it does,” with “surprising” being the operative word?

“One’s initial response to a new Bowie album,” cautioned Goldmine, “depends largely upon how one dealt with his last decade’s worth of creative tomfoolery. The false dawn of Tin Machine notwithstanding, the general consensus is that Bowie cashed in his iconographical chips the moment Let’s Dance went stellar, and that subsequent albums were less a reflection of his personal prides and prejudices than they were a callous conceit aimed at retaining a fame which he’d hitherto only been able to conjecture. But when the mythical Ziggy reached his peak, he died. When Bowie got there, he simply went soft. Expectations went the same way shortly after.”

Maybe it was the knowledge that he no longer had anything left to live up to that powered 1.Outside. Bowie personally hadn’t reached for heights like that since Scary Monsters, an album that might have looked at the world outside for ideas, but took its inspiration wholly from within.

Even more surprising was the fact that, even though 1.Outside retained its concept-album sheen, Bowie and Eno spent more time conspiring than perspiring, creating a work that avoided traditional concept-album traps (Tommy, can you hear me?) by upping the musical stakes whenever the narrative slipped. Neither was the story too obtrusive. Occasionally, the listener might look up, wondering precisely what was going on, but otherwise, 1.Outside existed so exquisitely within and without the strictures of its premise that Virgin thought nothing of preparing a promotional vinyl version that stripped away a lot of the album’s segues and spoken word segments, and concentrated on the music alone.

It was fabulous. Its best tracks — the grinding “The Heart’s Filthy Lesson,” the sinister and singalong-like “I Have Not Been to Oxford Town” and the Eno-infested “No Control” included — highlighted Bowie the songwriter, as opposed to the groove-mood merchant of too many recent efforts. Similarly, the newfound awareness of his own heritage that had so graced The Buddha of Suburbia was revised to lace 1.Outside with some of the best musical in-jokes he’d ever told.

All Stonesy riffs and echoed mumbles, “Hallo Spaceboy” wouldn’t have been out of place propping up bonus tracks on the Diamond Dogs reissue. Elsewhere, Garson contributed some wonderfully Aladdin Sane-ish flourishes to the proceedings (notably on “The Motel”), while a nearby box of vari-speed tricks allowed everyone from the Laughing Gnome to the Thin White Duke to take a fleeting bow.

What was most astonishing, however, was just how unselfconscious it all seemed, as though Bowie was referencing his past as much for his own sake as the listeners’, planting landmarks in some increasingly unfamiliar territory, while everything else slammed into overdrive.

“Is 1.Outside the ‘return to form’ which most Bowie fans long gave up hope of hearing?” Goldmine asked in conclusion. “Instinctively, the answer is no, but what is ‘form’ for Bowie, anyway? Ziggy was not Low was not Young Americans, and 1.Outside is none of them. The fact that it can be mentioned in the same breath as those albums, though, should count for something, as should the fact that, for the first time in too long, Bowie sounds like he actually means what he’s singing, and isn’t simply making an album because it’s less mess than washing the dog. ‘Or, in other words . . . no, he said it best. ‘Not tomorrow. It happens today.’”

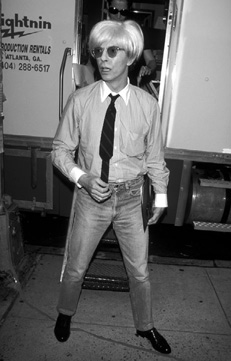

Awaiting the release of 1.Outside, Bowie took the opportunity to sublimate, to immerse himself in a personality that had long fascinated him, as he took on the role of his own idol, Andy Warhol, in director Julian Schnabel’s biopic of the New York painter Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Basquiat is frequently cited among Bowie’s finest cinematic performances, and that despite the movie itself often being very hard going. Basquiat’s story is deeply depressing, even before it culminates in his drug death in 1988, and a powerhouse cast (Dennis Hopper, Gary Oldman, Willem Dafoe and Christopher Walken all appear) often overwhelmed the tentative nature of the plot and script.

Warhol’s presence in the movie was minimal. With only a few words of script to deliver (“Once I got them in the right order, it was a doddle”), Bowie completed filming his role in just ten days, but he admitted that his favorite part of the otherwise “vegetating” process of moviemaking was the fact that he didn’t need to leave New York. “When they finished with me, I could just wander off and go to a record shop.”

“I met Andy a number of times,” he continued. Their famous first encounter took place in late 1971 when Bowie visited the U.S. to sign his RCA contract. He played the painter a song from his forthcoming Hunky Dory album, the homage, “Andy Warhol.” “He absolutely hated it. He was cringing with embarrassment” — more to Warhol’s tastes were the canary yellow shoes Bowie was wearing at the time. The American took a string of Polaroids of them and, as they parted, he murmured, “Good-bye David. You have such nice shoes.”

Looking every inch a Warhol superstar, Bowie on the set of Basquiat, June 1995. (© RON GALELLA/WIREIMAGE.COM)

“I never knew the guy,” Bowie continued, “but I’d seen him sufficiently to understand his body language and how he looked, how it felt to be in his company. He had this kind of cold fish thing about him. And this caked skin. It was a sallow, yellowish-tinged thing, as though it was made out of wax.”

Bowie would wear some of Warhol’s own clothing for the shoot. “We got all his clothes and his wigs and his eyeglasses from the Pittsburgh museum, so I was wearing Andy. I was in there. And I don’t think the clothes had been washed. There were just hints of the fragrance he wore on them.” Equally fascinating was “this little handbag that he took into hospital with him . . . a very sad little bag with all these contents: a check torn in half, an address . . . and a phone number . . . this putty-colored pancake that he obviously used to touch himself up with before he went public anywhere . . . loads of herb pills.” A couple of times, Bowie kept the clothes on once filming was over, and paid visits to the artist’s old neighborhood in Soho, eight years after Warhol’s sad and lonely death, just to see how people reacted. The results, he cackled, were “So bizarre! People were nearly dropping on the street. I loved it. I had a couple of days of just feeling like a practical joker.”

Another diversion came in the form of Bowie’s first-ever retrospective art exhibition, staged at the Cork Street gallery in April 1995, and stuffed with wall-to-wall paintings, sculptures, charcoals, computer-generated pieces, posters, a handful of collaborations with South African Beezer Bailey — even wallpaper, an addition to Bowie’s creative arsenal that set the critical establishment howling, which in turn placed Bowie himself firmly on the defensive.

In 1994, he had told Mojo, “Brian [Eno] and I want to do a book of wallpapers, D.R. Jones & Son, Wallpaper Merchants, thinking what I might have done had I not been lucky and ended up in the, er, artistic field. We’re looking for embossed plain white fifties wallpaper we can put our designs on and bind in a big plastic-covered book with brass screws from which you order.”

Now he continued, “I’d been very impressed by artists who did art pieces on wallpaper. Warhol had done some, and this girl [Laura Ashley] in London did one of bloody handprints . . . so I did a mock-up of a Damien Hirst box, with a portrait of Lucien Freud inside, and one of a Minotaur with a large erection. They were never on sale as wallpaper, and never intended for a decorator shop.” But, of all the exhibits at an altogether cautiously received exhibit, it was the wallpaper that drew the most scornful comment, and continued to do so (“That is so unfair!” erupted Bowie after one more journalist raised the subject). Meanwhile, 1.Outside engineered a critical rehabilitation he’d almost forgotten how to enjoy.

“I can’t believe how well it was received! To have an album that was liked by both NME and Melody Maker is quite something these days, isn’t it? Especially for someone of my generation.”

He took grim satisfaction, especially, in the ease with which the new album surprised people. They were all, he mused, expecting some kind of Enossified follow-up to Black Tie White Noise; Let’s Dance Ambient Style, perhaps. Instead, he preferred to view it as the logical successor to an album that most critics were not even aware of, but which they were now scrambling back to, in search of clues. They found them aplenty.

“In terms of personal success, The Buddha of Suburbia . . . [is] a really excellent album,” Bowie said, “but I don’t think the critics at the time saw that one at all, I don’t think they bothered with it. But the interesting thing is that it’s an excellent bridge album between Black Tie White Noise and this present one. Listening to Suburbia, you can almost feel the way I’m going.”

With 1.Outside scheduled for a September release, the subject of a tour inevitably arose, much to Bowie’s dismay. It had been four years since he was last on the road with Tin Machine, and he was delighted to discover that he didn’t miss it at all. He was much happier at home with Iman, simply doing the things that all married couples enjoy doing: “being boring,” as she once laughed.

At the same time, however, there was no denying that at least a handful of shows — Bowie agreed to a half dozen — would not go amiss in the marketplace, so, in May 1995, he began making arrangements with much the same core of musicians as had cut the album, Alomar, Garson and Gabrels. Sterling Campbell was also invited along, but he had duties elsewhere. He’d been invited to join Soul Asylum, “a real opportunity to join a group proper.” In his stead, he suggested Bowie try out Zachary Alford, Campbell’s best friend and the percussive power behind, among other things, The B52’s and their eighties-ending album, Cosmic Thing. (He’d also played alongside Bruce Springsteen and Billy Joel.) Bowie heard Alford play and wholeheartedly agreed with Campbell’s recommendation.

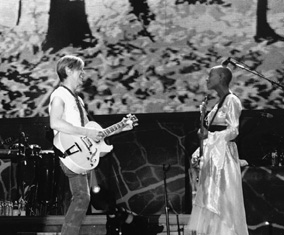

The other newcomer was Gail Ann Dorsey, a Philadelphia-born bassist who’d spent the previous decade accumulating some truly magnificent musical credits, ever since she arrived in London in 1985 and was drawn immediately into Rolling Stone Charlie Watts’ Big Band aggregation. Sessions alongside the likes of Boy George, Ann Pigalle and Thrashing Doves followed, while Dorsey’s solo aspirations were slammed into prominence when she appeared on British TV’S The Tube in 1986, accompanying herself on bass guitar alone, for a magnificent rendering of Bobby Womack’s “Stop On By.”

Dorsey cut her first solo album, The Corporate World, the following year. With guest appearances from Eric Clapton, Anne Dudley and the Gang of Four’s Andy Gill, the album landed a Top 10 hit in the Netherlands, and sent Dorsey and her band off on tours that included a massively over-subscribed showing at the ICA, and an opening spot (for Aztec Camera) at the Royal Albert Hall.

A wealth of further session work kept Dorsey away from her own career for another four years. Her second solo album, Rude Blue, was finally released in 1992, before disagreements with her label of the time, Island, saw her abandon London and relocate to Woodstock, New York, and an ever-expanding diary that included stints with the Gang of Four, The The and Roland Orzabal’s oneman Tears for Fears reunion. She was considering a new solo album, with Orza bal at the helm, when Bowie rang.

“Believe it or not, I actually got a telephone call from Bowie himself, completely out of the blue! I was in the middle of recording what would have been my third solo album. It was some time in May of 1995. I thought one of my English friends was playing a trick on me!” Bowie later told her that he was among the amazed millions who had caught her performance on The Tube, and had been thinking about working with her ever since. Her performance at the “audition” a few days later convinced him that his instincts were correct.

Shown here almost a decade on from Outside, Gail Ann Dorsey remains one of Bowie’s longest serving lieutenants. (© MARTYN ALCOTT)

Virgin, on the other hand, were determined to prove that his low-key touring plans were misguided, and brought out a folder stuffed with reviews to further their argument. 1.Outside had received the most positive response of any Bowie album in years — it had reached Number 8 in Britain, Number 21 in the U.S. — he would be mad to allow the buzz to dissipate. Finally, Bowie agreed. Six gigs expanded to six weeks touring the U.S. alone, with a European tour to carry the party into the New Year. Hastily, his bandmates rejigged their own schedules, while Bowie concentrated on how to help his audience rejig their expectations.

Five years earlier, Bowie had insisted that he had finally laid his greatest hits to rest. Selecting a repertoire for the Outside tour was his chance to prove it, even as the lessons of Tin Machine reminded him that he could not, once again, go out with an altogether unfamiliar show. Instead, he needed to seek out a middle ground, one that would give the fans something they knew well enough to sing along with, while insulating him from the nightly horror of revisiting Sound + Vision.

“I don’t like soft options,” he would remind anyone who’d listened. “I really want, for the rest of my working career, to put myself in a place where I’m doing something that’s keeping my creative juices going, and you can’t do that if you’re just trotting out cabaret-style big hits.”

Slowly, a set began to coalesce in his mind. He was digging in to the darkest corners of his catalog in search of songs that had never been given a fair crack.

“I’d love to do Lodger-period songs like ‘Yassassin’ and ‘Teenage Wildlife’ live again,” he told Mojo. “I like listening to my records a lot — I’m not going to lie, ha ha — and I compile cassettes of the obscurer stuff for the car. It would be wonderful to play live stuff I want to hear myself. Before, I tended to pander to the audience.”

The set list came together intuitively. “Scary Monsters,” “Look Back in Anger,” “Breaking Glass,” “Joe the Lion,” “Nite Flights,” “Boys Keep Swinging,” “DJ”. . . there were a few hit singles in there, but nothing obvious, nothing overt and, most important, nothing grating. “I prefer a magnificent disaster to a mediocre success. I cannot, with any real integrity, perform songs I’ve done for twenty-five years. I don’t need the money.”

“Andy Warhol,” “Diamond Dogs,” “Moonage Daydream” also made appearances. Discovering that Dorsey sang as well as she played, Bowie even revived “Under Pressure,” to leave the bassist thrilling to the prospect of recreating one of her own most beloved duets with Bowie. “Queen is my favorite band of all time, and I remember being so overwhelmed at Bowie’s suggestion that I cried. To sing a part originally sung by Freddie Mercury so far has been the greatest honor of my life.”

Bowie himself was staggered by Dorsey’s performance. “She sings her tits off on that thing. Boy she’s good, and I’ve got to follow that every night.” Almost a decade later, he admitted, he still trembled at that thought. One reason why he reintroduced “Life On Mars?” to the repertoire, he said, was so he could “look back at her and [making a taunting noise]. It’s the only thing that will stand up to that bugger.”

Nevertheless, you know that you’re in the presence of truly obscure ambition when the best-known song turns out to be one that most of the audience thinks is a cover. Six months earlier, Nirvana had released Unplugged in New York, a live recording taped for MTV just months before Kurt Cobain’s suicide. Mingled in with the expected favorites and some surprising tributes was a genuinely triumphant version of Bowie’s own “The Man Who Sold the World.” It was so triumphant, Bowie laughed once the tour was in motion, that half the audience was on its feet applauding him for even knowing the song. “They think it’s really cool that I covered Nirvana.”

Bowie and Dorsey, Staten Island, November 2002. (© SIMONE METGE)

For his own part, he was happy to admit that it was cool that Nirvana covered him. “I thought it was [an] extremely heartfelt [version],” he said, before admitting that only over the past few years had he realized just how heavy an impact this music had had on an American audience.

Trent Reznor’s love of Low was only the tip of the iceberg.

“I’ve been finding all these interviews with people like Trent Reznor, Smashing Pumpkins and Stone Temple Pilots, where they refer to my music as very influential in what they’re doing. It really is wonderful for the ego! It hadn’t occurred to me that I was part of America’s musical landscape. I always felt my weight in Europe, but not here. It’s great that I feel my music finally means something in America more than just a ‘Let’s Dance’ single; that it actually has some contributions to make to the complexity of music over here. It’s lovely.”

Now he was to offer something back. In the minds of the hide-bound promoters wedded to the habits of the past, Bowie was the star attraction on the upcoming tour. In the eyes of the kids who were lining up for tickets, however, it was Nine Inch Nails — Bowie’s personal choice for the evening’s opening act, and the vehicle through which the comeback kid would receive the most mortifying baptism of fire.