Just a month after they wrapped up the ballroom mini-tour in September 1996, and with the new album (already christened Earthling) completed, Bowie, Gabrels and Dorsey were gigging again, with a pair of appearances at the Bridge School benefit gigs that Neil Young had been organizing since 1986.

Sharing a bill that, with the event’s characteristic quirkiness, went from Billy Idol to Patti Smith, and from Pearl Jam to Pete Townshend, Bowie chose to serve up a lighthearted, almost joke-laden ten-song set. It spread across brief versions of the R & B pounder “I’m a Hog for You, Baby” and the vaudevillian “You and Me and George,” through the expected “Heroes” and “The Man Who Sold the World,” and onto a triptych that few people ever expected to hear again, “The Jean Genie, “Let’s Dance” and “China Girl.”

Before the howls of betrayal could arise from the ranks, however, you needed to check out what he did to them first, rearranging “Let’s Dance,” in particular, in so dramatic a fashion that the closest comparison would be the utter rewiring of the “Jean Genie” intro with which he’d tormented audiences back in 1974. If any proof was required that, after so many years of uncertainty, Bowie had relaxed back into his creativity and rehabilitated his repertoire, that was it.

In 1990, Sound + Vision’s largely cosmetic revisions notwithstanding, Bowie considered himself a prisoner to his catalog. By 1996, he had again mustered his talents, playing songs because he wanted to perform them, not because an audience expected or demanded them. From here on in, his past was his playground, a point he chose to confirm as the year wound down, and he began preparations for what was the biggest chronological milestone of his life so far: his fiftieth birthday.

When you’re young, fifty is one of those scary shadows that lurks off in the future, a generation that seems impossibly ancient, hideously decrepit, closer to the grave than the cradle and just a few blinks of the eye away from retirement. Once it arrives, however, how much has really changed? Bowie at fifty felt almost the same as Bowie at forty . . . thirty . . . even twenty. It was the years that had passed, not his imagination, and as the big day approached, his urge to celebrate that fact grew more and more pronounced.

There was also a sense of prophetic fulfillment. Back around the time of Lodger, when a thirty-two-year-old Bowie was asked how he felt about aging by Daily Express journalist Jean Rook, he told her, “an aging rock star doesn’t have to opt out of life. When I’m fifty, I’ll prove it.”

Now he was to do just that. “I want to see what you can do as a rock artist at fifty,” he mused. “More than at any time in my life, I’m comfortable with people and myself. At one point in my life, I would have a relationship with a city, but not the individuals. I would open myself up to a city, but not the people in it. A city wouldn’t talk back, it didn’t ask questions, it didn’t want anything.” That alienation, he insisted, was utterly swept away now, by his marriage to Iman, by the renewed self-confidence that permeated everything he attempted. Now it was time to celebrate.

The birthday celebration show was booked into New York’s Madison Square, a betrayal, perhaps, of Bowie’s London roots, but a sensible decision from a logistical point of view. Bowie’s entire crew was American, his musicians were largely based there. “Economically, it was far more feasible to do it in the States than take all the caboodle back to Europe.”

British fans were compensated with the knowledge that the show would be broadcast live via pay-per-view television, while a visit to the BBC a few days before the concert saw Bowie and band record a magnificent nine-song session for radio broadcast on January 8, as Changesnowbowie. Echoing the Bridge School concerts setup, the set featured Bowie, Gabrels and Dorsey alone, and was recorded all but live (“six lead vocals in two hours,” producer Mark Plati later marveled) and rounded up an eccentric smattering of songs that wandered as far afield as Tin Machine’s “Shopping for Girls” and Ziggy Stardust’s “Lady Stardust” in search of surprises.

Still, the broadcast was no compensation for missing the main event, a gig which, long before the doors were opened, was being spoken of as one of the greatest concert events in Bowie’s entire career.

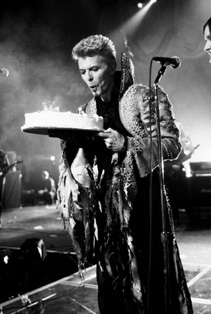

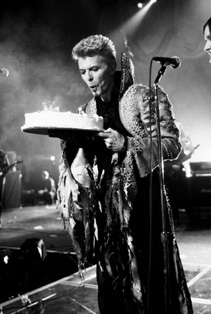

You need a big cake to hold 50 candles — the finale at Madison Square Garden, January 1997. (© KEVIN MAZUR/WIREIMAGE.COM)

From the outset, Bowie intended to have a party in every sense of the word, a celebration of his half-century on earth to be attended by a guest list of similar import. True, the growing list of celebrity attendees did raise some eyebrows. Bowie seemed to ignore many of the names that the fan club would have thrown into play (no Iggy Pop, no Eno, no Suede, no Goldie, not even Trent Reznor). But Lou Reed was invited, together with an arsenal of names that, though they may not have been instinctively linked with Bowie, certainly displayed just how far-reaching his influence and his musical tastes were.

Sonic Youth and the Pixies’ Frank Black represented the dawn of the decade, and Bowie’s excitement at the new music growling out of the American college underground. Dave Grohl’s Foo Fighters nodded toward Nirvana’s role in reawakening Bowie’s curiosity about his own past. The Smashing Pumpkins’ Billy Corgan spoke to the still-reverberating impact of Bowie’s Ziggy years on modern music; and The Cure’s Robert Smith acknowledged the permanency of that same impact. The Cure were on the brink of their own twentieth anniversary. Smith has never made any secret of his love of vintage Bowie; he was even responsible for one of the most remarkable covers of a Bowie song ever waxed, a tremulous take on “Young Americans.”

Smith’s love of Bowie’s music was not unequivocal. “Tin Machine was a complete waste of time,” the singer sniffed. But still, Smith admitted, “David Bowie is the only living artist involved in music who’s ever had a real impact on me . . . despite the fact I’ve said I don’t like a lot of what he’s been doing.” Indeed, while cynics could complain that many of Bowie’s guests were selected with at least one oddly colored eye on their bankability, among the handful who could be said to enjoy a truly symbiotic relationship with Bowie and his music, Smith’s presence was a genuine highlight, for himself as much as for the audience. “I grew up idolizing Bowie and I really do respect what he does.”

From the outset, Bowie was determined that the show would not simply be a celebration of the past. He had a new album completed, after all, and he was anxious to let it be heard. Seven of the twenty-three songs would be drawn from the new album, with their impact deepened by Bowie’s decision to share the bulk of them with his guests. Dave Grohl appeared on “Seven Years in Tibet,” Sonic Youth helped demolish “I’m Afraid of Americans,” Robert Smith would co-host “The Last Thing You Can Do” (one of the more Jungle-influenced numbers on the new album, and one that Bowie himself had only just decided to include on the record). He spent most of the sessions considering it as a B-side, but time has vindicated his change of heart. It would emerge as one of the album’s strongest tracks.

For Robert Smith, the meat of the moment came immediately after, as he and Bowie launched into one of Smith’s own favorite oldies. When he was first approached to play the show, Smith was hoping to convince the star to unearth “Young Americans.” Instead he was handed “Quicksand,” and he acknowledged how unutterably “weird” it felt, “getting up there and singing one of the Hunky Dory songs.” Smith was a thirteen-year-old fan when he first heard that album, and it had lived ever since among those peculiar psychic crutches that everybody accumulates at such an impressionable age. Now here he was on stage, alongside Bowie, singing a song he’d previously only ever performed in front of his bedroom mirror.

By the time Smith made his way out on stage, the show was already close to an hour old (plus a dynamic opening set from Placebo), so audience preconceptions were still being kicked back into touch. A newly designed stage set brought bouncing eyeballs and mutant mannequins into play, while “Scary Monsters,” “Fashion,” “The Heart’s Filthy Lesson,” and a positively manic “Hallo Spaceboy,” nailed down by no less than three drummers (Zack Alford plus the Foo Fighters), had reduced the most cynical onlooker to jelly.

And it only got better: a driving “Under Pressure,” a soaring “Heroes,” a frantic “Voyeur of Utter Destruction”. . . and then it was time for Lou Reed to appear, and the hometown crowd went crazy. “Looking over to see Bowie and Lou Reed together was the greatest thrill for a little girl from Philadelphia,” Gail Ann Dorsey later admitted, and she was not alone in that judgment. Stunning though much of the show was, it was difficult to shake the feeling that many of the guests were interchangeable, with only Smith truly willing to actually play with, as opposed to alongside Bowie. But, from the moment Reed stepped out on stage, even Bowie knew that now he was really going to have to fight to keep the spotlight.

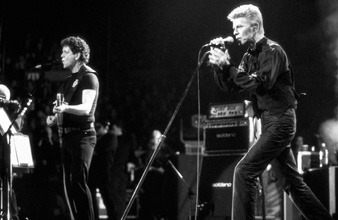

Bowie and Lou Reed at the birthday concert — the first time they’d shared a stage in 25 years. (© KEVIN MAZUR/WIREIMAGE.COM)

“The King of New York himself,” announced Bowie, above the crowd’s own overture of booming calls of “Loooooooooou.” Reed was grinning widely even before the pair slipped into the staccato acoustic riff that announces “Queen Bitch,” the song that the young Bowie wrote in direct tribute to the Velvet Underground (“Some white heat returned,” read his scribbled annotation on the Hunky Dory album sleeve), and which still echoes the sheer weight of influence that Reed and the Velvets exerted on Bowie’s fledgling career. When Reed slid in to monotone the final verse, we finally heard the song as its writer had first envisioned it.

“Waiting for the Man” followed, a driving, squalling stamp through the Velvets’ gem that Bowie had been performing for more years than any other song on display that evening (he taped his first version in 1968, the year before he wrote “Space Oddity”). The singers traded lyrics as though they were in an actual conversation (Lou: “Hey white boy, what you doing uptown?” Bowie: “Oh, pardon me sir . . . ”); and propelled by an Alford-Dorsey rhythm that never sounded so tight.

Another Reed song, “Dirty Boulevard” (from his 1989 New York album) followed. Then it was back into their shared past for a scything rendition of “White Light White Heat.” Later, once the show was over and the crowds were streaming home, it was hard not to shake the sensation that somebody totally screwed up the evening’s running order. Reed ought to have climaxed the event; had, in fact, done so, long before Dorsey led the crowd in a mass singalong of “Happy Birthday,” before Billy Corgan was reeled out for two final numbers, “All the Young Dudes” and “The Jean Genie,” and before a visibly emotional Bowie strummed out a gentle, beautiful “Space Oddity,” bathing in the knowledge that, by playing “The first hit that I ever had, it really seemed like the fulfillment of some kind of cycle.”

Afterward, the reviews were rabid in their admiration of the night. But, most of all, the evening was dignified by the fact that Bowie never once allowed the proceedings to collapse into a back-slapping festival of nostalgia and tears, a long parade of memories that owed nothing to his present. “I don’t mind one moment like that,” he mused, with that tearjerking “Space Oddity” firmly in mind. “I just didn’t want the whole show to degenerate into that kind of ‘oh, do you remember what we were doing this night?’ I hate going to shows like that, because I feel manipulated.” Besides, he’d already done that when he was forty-three and flailing. At fifty, he was fit. There was no reason at all to look back.

Occasionally, critics may have expressed their regrets at the omissions they’d noticed. But few complained about what they did receive, and most agreed that anything more (or less) than Bowie gave them would have betrayed the birthday boy’s own vision of his career. “More than most performers his age,” the New York Times solemnly declared, “Bowie has repeatedly staked his career on the new.” Why should he change now?

The release of Earthling in February 1997 confirmed the boldness that had blared out of Madison Square, both in musical terms and in the eyes of critics who viewed even 1.Outside with wary suspicion — “The sound,” as Alternative Press sniffed, “of a man clutching straws, hauling himself out of the tar-pit of irrelevance by latching onto the first passing bandwagon he could reach.” Earthling, the same organ concluded, still wasn’t “firing on all cylinders, but if you could cram the best of 1.Outside down to half its length, and get a great single album, Earthling could dump just two songs and turn into a classic.”

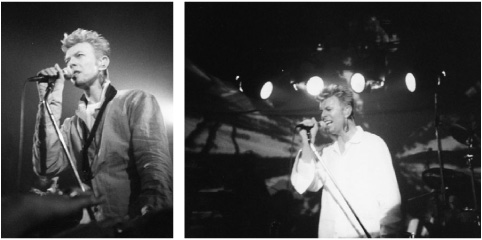

Bowie and Reeves Gabrels during the Earthling tour, London 1997. (© BIANCA DIETRICH)

Initial impressions of Goldie meets Nine Inch Nails were certainly dismissed as the album (and its maker) gained confidence. Bowie also pushed memories of 1.Outside out of his system as swiftly as possible, ditching mood for music and getting back to actual songwriting, as Robert Smith later explained. “I really liked Earthling. I thought it was a really good album. The songs are great songs, they really stand up to be listened to as songs, and the fact that he worked in a particular genre and tried to capture a certain sound is neither here nor there. The songs are really well put together.”

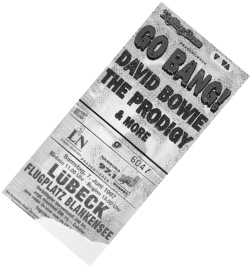

The album’s musical influences were plain: the ferocious techno of The Prodigy was especially prominent, while Goldie himself enthused, “I think it’s really wicked that Bowie can get inspired by what we do. I love the amount of people from any genre coming to check it. I don’t think everyone should slate him down ’cos I don’t think they have a right to do that. Bowie is Bowie, end of story.”

Nevertheless, Bowie did his best to discourage fans from prejudging the album from its early publicity. “I’d hate the impression to be that it’s overridingly jungle. This record owes a debt to drum ’n’ bass in the use of rhythm, but . . . what we are doing is a million light-years away from what, say, Goldie would be doing, or any number of other drum ’n’ bass purists.” He then proved that point by guesting on Goldie’s next album, Saturnzreturn, turning in a fine vocal performance on a song, “Truth,” that could never have fit onto Earthling.

“Working with Bowie was just insane, man,” Goldie confessed. “I was in the control room and he was in the room just standing there in front of the mike, chain-smoking cigarettes. So I was basically directing him, telling him what I could see in my head. He was great, totally tuned in. He’s the other side of the glass and I’m telling him what to do. I tell you what, I was laughing my bollocks off, man. I mean, David Bowie being told what to do by me!”

Touring for the new album was not scheduled to begin until June. From the moment Earthling touched down, however, Bowie and the band were riding through a succession of TV engagements and public appearances (on February 12, the reluctant movie star even unveiled his own star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame), a block of bookings that chased them through until April, when rehearsals for the new tour kicked off in earnest.

There was one return to the studio during this period, as Bowie cast his eye across a land he had long loved, but had only ever embraced from the stage in the past: Hong Kong.

The island was in the last months of its century-long life as a British colony. Later in the year, this tiny bastion of western capitalism would be formally returned to communist China, an event that left both locals and outsiders nervous about what the future might hold. Bowie had played there on several past occasions, and was always overwhelmed by his reception.

Now, however, it was uncertain whether he would ever be able to visit again, not only for cultural reasons (only a handful of western rock acts had been permitted to visit China in the past), but also for political ones. Bowie has never made any secret of his support for the oppressed nation of Tibet and his admiration for the exiled Dalai Lama, subjects that the Chinese government refused even to comment upon. Both subjects were referenced in his music and conversation; Earthling, however, included his most unequivocal commentary yet, the song “Seven Years in Tibet.”

As a teenager, falling into the seductive thrall of Tibetan philosophy, he explained, Heinrik Hasser’s Seven Years in Tibet“was crucial for me. It seems a little dated now, but in my teens it made a major impression on me. I just wanted to be Tibetan. I wanted my eyes and skin color to change, I wanted short black hair and saffron robes. I met a Tibetan at that time, a monk called Chimi Yong Dong Rinpoche, and he told me I was out of my mind to want to be a monk. Best piece of advice I was ever given!”

Still the fascination remained, to percolate through Bowie’s songwriting. As far back as his first album, songs like “Silly Boy Blue” and “Karma Man” reflected his interests. Now, Hong Kong DJ Elvin Wong was suggesting that Bowie transform this latest example from mere commentary to something more lasting.

“Elvin asked me why I wrote [the song] ‘Seven Years,’” Bowie recalled, to which he reiterated his own outrage at the continued exile of the Dalai Lama from his spiritual homeland. “[He] suggested it might be a first-class thing to record [the song] in Mandarin Chinese, to further assimilate that knowledge to another part of the world, a more Asian part of the world. I jumped at the chance, I thought it was a very impressive idea, and thought it was a great challenge.”

Bowie was no stranger to recording in foreign tongues. As far back as 1968, he’d taped three of the songs planned for his Love You Till Tuesday movie in German; the following year, he cut French and Italian renditions of “Space Oddity,” for release in those markets. 1977 brought German and French takes on “Heroes,” 1991 saw him voice Tin Machine’s “Amlapurna” in Indonesian. Those efforts, however, were enacted primarily for commercial reasons, or as special “gifts” for loyal local audiences. This time around, however, Bowie had a larger political agenda, and he was intent on doing everything correctly.

Long before the Earthling tour began in June, Bowie and co. were making numerous appearances to promote the new album. (© FERNANDO ACEVES)

While Wong sought out translator Lin Xi, and arranged for a local singer to record a demo for Bowie to follow, Bowie himself sought out a tutor to help him master the actual pronunciation. He discovered her in Dublin, “a Taiwanese girl who spent some years in Hong Kong and now worked in a translation center. She coached me [on pronunciation] for two or three days, and then we went into the studio.

“Apart from the nature of the song itself, I quite enjoyed the process of recording in Mandarin Chinese. I found it quite a challenge, and one I really welcomed. Any means of communication should not be closed, so it seems an interesting and logical step to take.” Retitled “A Fleeting Moment” for the regional market, “Seven Years in Tibet” rewarded Bowie by topping the Hong Kong charts at exactly the same time as the Union Jack was drawn down for the final time over the island. (A second Mandarin recording, “Looking for Satellites,” remains unreleased.)

The Earthling tour kicked off on June 2, 1997, with a pair of warmup shows at London’s Hanover Grand. The outing would consume the remainder of the year, and Bowie’s enthusiasm for another six months on the road, so soon after coming off the 1.Outside jaunt, surprised many observers. He never, in the past, seemed to enjoy the life of a road rat, but he sincerely believed that he had no choice. “Honestly, it would be a sin not playing live when I’ve got a band like this.” Again he reiterated the strength of the combo in the only way that the watching world would understand. “They’re the best group I’ve had in twenty years, right up there with the Spiders,” he told Q, and the shows that were to follow would reemphasize that fact.

Bowie’s revival as a working rocker, as opposed to the dilettante superstars who only stir from their ivory tower when it’s time to stage “an event,” was not wholly unprecedented. Almost exactly a decade before, in June 1988, Bob Dylan — a man whose own reclusion could make Bowie’s periodic silences seem positively deafening— set out on the first shows of what his own legend now describes as “the never-ending tour.”

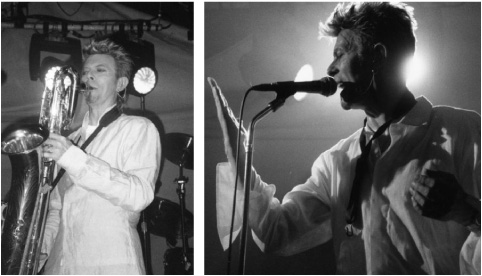

The sax was back for the Drum and Bass set — chilling at the Hanover Grand. (© GRAHAM MCDOUGALL)

Since that time, Dylan had played close to 800 shows all over the world, and he admitted, “There are a lot of times when it’s no different from going to work in the morning. Still, you’re either a player or you’re not a player. If you just go out every three years or so, like I was doing for a while, that’s when you lose your touch. If you are going to be a performer, you’ve got to give it your all.”

Bowie arrived at the same conclusion. He learned, too, that a performer must use all the tools at his disposal, not merely to keep audiences happy, but to keep himself happy as well. Dylan accepted that when he first began digging in to the darkest recesses of his back catalog, his record collection, his very memory, in search of songs to perform, and wound up not only salvaging oldies that most fans expected never to hear him play again, but breathing new life and meaning into them.

Bowie was now doing that, too. At the birthday concert, when he finally lifted his long-imposed embargo on “Space Oddity”; at the Changesnowbowie session, where he reawakened “Lady Stardust” and “Shopping for Girls”; and in the Dublin rehearsals for the Earthling tour.

With an eye for his growing acceptance on the techno dance floors, the band polished up new versions of “V-2 Schneider” (from “Heroes”) and “Pallas Athena” (from Black Tie White Noise). With an ear for all that the song evoked, he resurrected “Fame” from the grave of the Sound + Vision tour, and then so violently reworked it that, by the time the tour was underway, it was meta-morphosing into a new piece of music altogether, the frantic semi-scat of “Fun.” And, with a nose for unconventionality, he suggested Gail Ann Dorsey take the microphone for an absolutely hypnotic run through Laurie Anderson’s “O Superman” — a number that didn’t always work as well as it could have, but which nevertheless gave even Bowie’s detractors pause for thought.

Neither was Bowie content to perform a conventional set. Instead, the opening shows at the Hanover Grand saw him divide the performance into two parts, first a regular live show, then a more specialized drum ’n’ bass set. It was a bright and brave decision. For those observers who did enjoy the second set, the Observer newspaper’s description of “the cast of Star Wars falling down a fire escape” was probably the most evocative. Either way, the performance ranked among Bowie’s most dramatic, and death-defying moves in years.

Unfortunately, those observers were very much in the minority, and the two-part show was quietly folded back into one. But Bowie was not disheartened; the drum ’n’ bass set remained in the repertoire, only now, he didn’t warn people it was coming. Later, having recorded the Amsterdam gig for the live album he was now planning, he pulled dramatic renditions of “V-2 Schneider” and “Pallas Athena” for release as a 12-inch single in their own right, pegged to his newly coined pseudonym, Tao Jones Index. Long before many listeners figured out what (let alone who) they were listening to, the single translated into one of the year’s most captivating dance floor specialties.

Back to basics — the second “rock” set at the Hanover Grand show. (© GRAHAM MCDOUGALL)

Emboldened, Bowie then decided to take the Tao Jones Index itself on the road, taking over one of the small, tented stages at that year’s Phoenix Festival to pound, once again, through a wholly drum ’n’ bass set. (He played a more conventional, headlining appearance there the following day).

The key to the affection with which the Earthling tour is remembered, however, is less in the songs that Bowie performed, but the reasons for which he performed them. For the first time, Bowie seemed to be playing for fun, and the feeling of the show relaxed accordingly.

One of the more disconcerting images from the Earthling stageshow, the disembodied faces gaze down on Mexico City. (© FERNANDO ACEVES)

Although the stage set was as impressive as ever, reprising the Madison Square setup of eyeballs and mannequins, his own sense of costuming was taking a back seat for the first time. Bowie was as likely to trot out in jogging pants and a T-shirt as in something more finely and deliberately tailored.

His asides to the audience sounded less forced than they ever had, and though the band was clearly adhering to a set list, still, there was a looseness to the proceedings that suggested they could just as easily have been winging it. Besides, has any David Bowie concert ever kicked off with a more heartwarming trilogy than the acoustic, and almost unaccompanied “Quicksand,” an energetic “Queen Bitch” and a romp through “The Jean Genie” that was suddenly transformed into the old R & B staple “Baby, What You Want Me to Do?”

What Goldmine termed “the most unexpected (not to mention uninvited) resurrection of the decade” continued apace when David Bowie launched his first American tour since the Outside tour, in Seattle on September 7, and turned in a performance that both defied and defiled the pop obituaries that had been so easy to write in earlier years.

Gone was the self-mythologizing monster of past tour extravaganzas; gone, too, was the self-aggrandizing turkey who had flapped distressedly around a disinterested stadium circuit two years earlier. This time around, few of his venues were larger than a medium-sized theater, and, nightly, a supremely confident Bowie removed even that distance. He might have been playing a club, 300 fans instead of 3,000 — and, if he didn’t make eye contact with every soul in the room, the giant eyeball balloons that he bounced through the crowd certainly did.

The oldies were each revived with a roar, but it was an indisputable measure of Bowie’s return to form that at least half of the songs from Earthling were greeted as all-conquering heroes in their own right. In a way, Earthling insisted that the eighties (or at least, Bowie’s approximation of them) had never happened.

For the first time in his post-Ziggy live career, Bowie appeared to actually enjoy playing with the oldies: the set bristled with as many mischievous musical asides as it did verbal ones, from the hint of “Time,” which Garson dropped in to the ending of one song, to the laughing reiteration of classic Mott the Hoople, which Bowie inserted into the final encore, an impassioned “All the Young Dudes.” “Hey you there, with the glasses,” he recited. “I want you at the front.” “Well, you there, with the goatee,” replied Goldmine, “we want you up there as well.”

Behind the scenes, Bowie was excitedly discussing the proposed live album, with enthusiasm for the project now ricocheting through the media and the fan base. Since 1973, every David Bowie tour except the 1976, 1990 and 1995 outings had received some kind of souvenir, be it the much-delayed movie of the Hammersmith Odeon show that marked Ziggy Stardust’s final resting place; the forewarning David Live set that signaled Bowie’s move into his Plastic Soul era; the abysmal Stage that contrarily converted him into a disgraced nightclub crooner; the glossy Serious Moonlight show; or the hyper-ambitious Glass Spider video.

The Earthling show ran the gamut of moods, from energetic . . .

. . . to contemplative. (© FERNANDO ACEVES)

For all their historic resonance (and obvious marketability), however, none of these earlier leviathans depicted Bowie with such raw honesty as a snapshot of the Earthling tour might have done. That much was plain even from the handful of broadcasts that the band made as the tour rode on: an appearance on MTV’S newly launched Live at the 10 Spot concert series, where Bowie was a last-minute replacement for the scheduled Rolling Stones; a shorter (four-song) set at the GQ magazine awards, as broadcast by VH-1; and, pioneering a medium that would soon become an industry staple, an Internet webcast of the entire Boston show, at a time when a mere handful of other bands had taken a similar step.

With the tour finally at an end, then, Bowie, Gabrels and Mark Plati set to work on remixing tapes for the live album. They envisioned a double set, concert highlights pumped by a couple of new studio recordings, of the mutant “Fame” / “Fun” and, offering a nod of acknowledgement to Dylan’s sterling example of never-ending touring, the Zim’s own “Trying to Get to Heaven.”

The ongoing saga of the live album did not consume all of Bowie’s attention as 1997 faded into 1998. He gladly joined the army of celebrities who turned out to mark the BBC’s seventy-fifth anniversary celebrations, by contributing to a supremely ambitious rendering of Lou Reed’s “Perfect Day,” a plaintive declaration of love whose original version, back on 1972’s Transformer album, was produced by Bowie. Broadcast as a television commercial for the first time in September (and released as an instant chart-topping single in December), Bowie appeared in two clips, singing the lines, “Just a perfect day” and “You made me forget myself.”

Reed insisted, “I have never been more impressed with a performance of one of my songs. I would like to thank the BBC for making this Perfect Day perfect.” Bowie, for his part, merely added, “It’s a way of saying thank you for the Flower Pot Men” — the 1950s-era children’s TV show that introduced an entire generation to such future British icons as Bill and Ben, Little Weed and a broadly smiling house that saw everything that took place in the garden. Throughout the Tin Machine period, Bowie loved to make references to the show, if only to confound his American bandmates.

Less enjoyable, but time-consuming all the same, was the minor furor that grew up around the release of the latest compilation of Bowie’s back pages, the Essential David Bowie collection that helped highlight another anniversary, 100 years of the EMI record company.

Released in the United States in November 1997, the package disappeared from the shelves almost immediately. Widely circulated reports that Bowie objected to the liner notes were quickly quashed by his own office — he didn’t like any of the packaging.

Reports on sundry Internet news sites claimed that the Thin White Critic was incensed that EMI’s choice of author, journalist Steve Gizicki, was not sufficiently “high profile” to pen the liners, although an off-the-record spokesman claimed that Bowie was more alarmed by the number of rudimentary errors included in the text than the status of the writer. Names were misspelt (Mott the Hopple!), relationships were misrepresented and, though much of it was nothing a good proofreader couldn’t have fixed, the fact that Bowie himself had already approved an entirely different packaging for release did rankle. The first he knew of the U.S. edition was when an associate spotted it in a record store!

Packing far superior photos, and impeccable liner notes by longtime Bowie buff Kevin Cann, the “official” version of Essential had already been released elsewhere around the world. It would make its belated bow in the U.S. in early 1998, around the same time as Bowie took another break from the ongoing live album to join the cast of his next movie, Everybody Loves Sun-shine, on the Isle of Man.

The latest in that long line of hitherto respectable gangland-meets-cultural-drama Britflicks that reach from Performance to Lock, Stock & Two Smoking Barrels, Everybody Loves Sunshine starred Bowie as the increasingly disillusioned veteran, Bernie, a Mr. Fix-It for a gang led by his old mate Terry (played by Goldie, whose performance reinforces the suspicion that he glowers and grins a lot better than he acts).

Slow in getting started, Everybody Loves Sunshine turned out to be slow in doing much of anything, and Bowie emerged with flying colors as the only major cast member who isn’t on screen long enough to disappoint. He appears for no more than 15 or so of the film’s 100 minutes and, when he finally vanishes, following a wild flourish of Absolute Beginners/Vendice Partners grooviness, one gets the impression that he’s getting out while the going is still (somewhat) good. It was one of his wisest moves all movie long.