1998 saw Bowie making headlines for reasons far removed from his musical, acting or even artistic endeavors, as a succession of magazine polls placed him among the richest musicians in the world, with an estimated worth of $900 million. It was a colossal sum, all the more so since, twenty years earlier, Bowie had publicly announced that he was “broke,” in the wake of his parting from Tony DeFries and MainMan.

He may well have been. It was not a cheap divorce. Besides, the bulk of Bowie’s income did derive from the years since then. Let’s Dance alone outsold the bulk of his “classic” seventies albums several times over, while the deals he signed with EMI America in 1983 and Savage a decade later had generated a sizeable chunk of change in their own right. To that, one can then add three astonishingly lucrative tours (damn the critics, Serious Moonlight, Glass Spider and Sound + Vision all did brisk business at the box office) and, to that, add back catalog sales, both over the counter to fans updating their vinyl collections, and to fans new and old en masse. In 1997, EMI (again) paid out $28.5 million for the rights to Bowie’s entire 1969–1993 catalog.

Now Bowie was looking to double that sum, as he contacted financier David Pullman to orchestrate what would become known as the Bowie Bonds scheme, a deal in which Bowie received a lump sum of $55 million, advanced against the future sales of that back catalog, a sum he intended using to buy MainMan out of his life.

In 1971, when Bowie had first contracted with DeFries, he had put his name to a ten-year deal that split the profits equally, fifty-fifty, between artist and management. Four years later, the terms of their severance retained that split for the music Bowie recorded prior to 1975, then reduced DeFries’ share to sixteen percent for the remainder of the original contract’s lifespan.

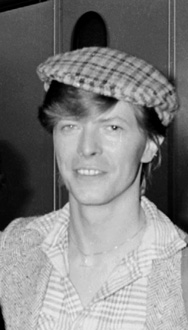

If the cap fits . . . the cheeky chappie awaits the end of the 1970s. (© PHILIPPE AULIAC)

Every time one of the songs covered under the agreement was played on the radio or TV, every time one of them appeared in a movie soundtrack, every time a record sold, a few more cents would drip into MainMan’s account. It was time, Bowie decided, to put an end to the agreement, via the payment of a sum that he could only produce through the most drastic measures.

The Bowie Bonds certainly fit that bill, laying Bowie open to all manner of scorn and amusement as his art and soul were transformed into a simple commodity, to be bought and sold like so many hotdogs. Soon, “Heroes” would be touting cameras on TV, “Changes” would be shoving something else down our throats.

The entire issue was purchased by Prudential Securities, but financiers and investors were not the only people taking a chance on the Bowie Bonds scheme. It involved a certain degree of compromise for Bowie as well. Announcing the deal, David Pullman enthused, “There is tremendous value in intellectual property — film libraries, record masters, literary estates — the value of it grows over time.” Nevertheless, in order to be able to pay back the full amount, plus interest, Bowie did need to ensure that his back catalog continued selling, and the only way to do that was to nurture it as lovingly as he promoted his latest albums.

The apparent ease with which he was now pulling the oldies out of the onstage closet was one of the ways in which this could be accomplished. Laying plans for a fresh sequence of repackages was another. The early 2000s would mark the thirtieth anniversary of Bowie’s breakthrough, and, already, he was preparing to celebrate the ensuing milestones with some quite spectacular editions of the albums that had ushered in, then confirmed, his ascendancy: Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane and Diamond Dogs would all reemerge in dramatically expanded form between 2002 and 2004, while 1974’s David Live and the 1978 Stage concert albums would both be dramatically revisited during 2005.

Despite such loving concern, however, the Bowie Bonds were not to prove especially successful. Trading in the shares was never especially vigorous, and, in March 2004, the financial experts at Moody’s Investors Service ruled that the entire stock was now valued at just one level above “junk,” the lowest rating any bond can be given.

The report acknowledged that the downturn was due in part to the financial difficulties assailing the music industry as a whole; it also referred to the “downgrade of an entity that provides credit support” to the bonds. All of which, the BBC thoughtfully translated, meant that “In practical terms, the bonds will fetch a lower price if fans — or anyone else — want to trade them.”

When Rolling Stone published its Top 50 rock ’n’ roll money-makers the following February, Bowie remained placed respectably at Number 17, his estimated earnings of $25.2 million in one year placing him fifth in a parallel poll of British acts (Elton John, Rod Stewart, Phil Collins and Sting pushed ahead of him). Anybody hoping to grow rich from the Bowie Bonds, on the other hand, still had a very long way to go.

Bowie did not allow his creative urges to be wholly subsumed by the theater of financiers into which he had suddenly fallen. Diversifying his interests as wildly as ever, but armed now with the wealth to follow them through, Bowie also made a significant investment in a new publishing company, 21 Publishing.

The first release appeared to typify what could be expected from the imprint: Blimey! From Bohemia to Britpop: The London Artworld from Francis Bacon to Damien Hirst was a study of precisely that, an engaging discussion on the development of British art from both an artistic and (more importantly, to Bowie, at least) a cultural point of view.

It was 21’s next major venture, however, that was to draw the most attention, as author William Boyd set out to document the life and times of the American artist Nat Tate, a figure whose contributions to modern art, said some of New York’s preeminent art experts at the book’s launch, were only amplified by the tragedy of his life. Tate committed suicide in 1960 by leaping off the Staten Island Ferry into the icy waters of New York harbor.

Nat Tate: An American Artist 1928–1960 was a beautiful book, with Tate’s past obscurity readily negated by the glowing words not only of the critical establishment, but also the art experts who lent their own thoughts to the book’s foreword. (Bowie himself contributed a laudatory essay to the tome.)

The fact that Bowie chose April 1, 1998 as the book’s launch date didn’t strike anybody as at all peculiar. Neither, initially, did the coincidence that Nat Tate himself appeared to be named for two of London’s premier art galleries, the National and the Tate. Nat Tate is not the most obscure name in the real world, as a visit to any Internet search engine will prove. In this case, however, it was not such a coincidence after all, although it was some days before the art world finally realized that the whole production was an elaborate, and beautifully crafted hoax. And, by that time, Tate, had he actually existed, had already been elevated to the realms of the post-war world’s most respected artists.

It was The Independent’s David Lister who unveiled the joke, just days before the volume’s UK publication, then followed up with his report of that event by remarking, “as a book launch, last night’s carved out a new aesthetic territory. Was it post-ironic, simply surreal or as abstract expressionist as Tate himself? An intended launch for a specialist art biography turned into a celebration of one of the great literary hoaxes.

“Last week, the New York art world was fooled . . . last night was to have been [Britain]’s turn. But, with the secret out, last night’s launch at a London restaurant allowed a celebrity guest list — including novelist Antonia Byatt, composer Andrew Lloyd-Webber and the BBC’s Alan Yentob — to bask in their lack of gullibility.”

Bowie was sufficiently disappointed by the unmasking that he canceled his plans to attend the London launch. Instead, he remained in New York for another few weeks, before flying out to Garfagnana, in Tuscany, to film his next movie, Giovanni Veronesi’s spaghetti western Il Mio West (a.k.a. Gunslinger’s Revenge): he played Jack Sikora, an aspiring gunslinger determined to kill a man played by Harvey Keitel, and proclaim himself the fastest gun in the West.

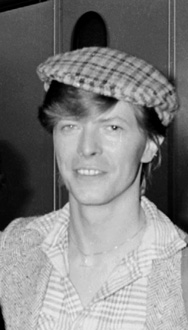

From Tuscany, Bowie made his way to Vancouver, Canada, to appear in the title role of director Nicholas Kendall’s Exhuming Mr. Rice (later retitled Mr. Rice’s Secret), a role which, as the first few moments unfold, looked as though it might be his slightest yet. The film begins with Mr. Rice’s funeral.

Shades of The Hunger quickly unfurl. In that movie, twenty-three years earlier, Bowie’s character was an impressive 200 years old. In Mr. Rice’s Secret, however, he reached a sprightly 400 before passing away, and he didn’t need to drink blood to do it. There is, however, a magic potion, and the movie concentrates on the attempts by a young neighbor, Owen (played by Bill Switzer) to rediscover Rice’s elixir of life. Flashbacks keep Mr. Rice in camera shot, and Bowie reveled in a role that allowed him to portray “the better qualities in all of us.” Mr. Rice himself, Bowie confessed, reminded him of his own father: “I keep getting images of my dad” (Bowie’s father, Hayward Jones, passed away in 1969, when Bowie was twenty-two); images that would ultimately lead to Bowie writing one of his loveliest ever songs, Heathen’s “Everyone Says ‘Hi’.”

Bowie explained, “I couldn’t actually believe he was not going to come back again. I kind of thought he’d just put his raincoat and cap on, and that he’d be back in a few weeks or something. And I felt like that for years . . . like [he had] gone on a holiday of some kind.”

Mr. Rice’s Secret was never intended to make a major splash; rather, it was a cute family-oriented offering that was initially planned to move straight to the TV screens. In the end, a brief tour of the European film festival circuit saw it pick up a string of awards before finally turning up on the Family Channel in late 1999.

Now that filming was over, Bowie next launched his tentacles into yet another medium, the Internet. Back in the early 1980s, as he toured the world aboard Serious Moonlight, Bowie grasped a handful of headlines by conducting most of the tour’s business via a newfangled device called “electronic mail”; an apparently paper- and postage-free means of communicating by computer.

Few observers paid it much attention: science was always coming up with these great new innovations that may or (probably) may not change the way we do something or other, and “e-mail” was probably just another one of them. File it alongside the transmit beams, robotic housekeepers and holidays on the moon that the future was always meant to hold for us.

Bowie, on the other hand, never lost faith in the system; nor in any of the many other computerized communications that evolved as the 1990s sped along. The World Wide Web, in particular, fascinated him, as the computer geek novelty of the early decade grew in a matter of a few short years to become the single most vibrant and expansive means of communication on earth.

It was a marketplace, of course. Although a lot of the bugs were still to be ironed out, by the mid-1990s it was clear that there was a lot of money to be made from the ’Net. But it was also a forum for talk, a repository for knowledge; it was everything and anything one wanted it to be, and several years ahead of any other major artist, Bowie understood precisely how much power was bound up within it.

“If I was nineteen again,” Bowie declared, “I’d bypass music and go straight to the Internet. When I was nineteen, music was still the dangerous, communicative future force, and that was what drew me to it. But it doesn’t have that cachet anymore. It’s been replaced by the Internet, which has the same sound of revolution in it.”

In September 1996, aware of the growing tide of downloadable music that was available on the ’Net was, Bowie became the first star of any stature to release an Internet-only single. Acting on a suggestion from Nancy Berry, executive VP at Virgin, a specially commissioned “Feelgood” remix of “Telling Lies” made available only via the net, and quickly notched up a staggering 250,000 downloads. No David Bowie single had “shifted” that many copies in years.

Bowie and Dorsey (far right) meet their public in Dublin, May 1997. (© ALEX ALEXANDER)

The following year, the webcast of his Boston concert became one of the ’Net’s most over-subscribed events yet, with so many users logging in that most people spent the entire concert simply trying to connect. Now Bowie was planning to launch BowieNet, a cyber home for everything and anything he imagined the ’Net to be capable of: downloadable music, diary entries, cyber chats for fans and special guests, advance warning of new releases and tours . . . just give the man your money, and BowieNet will do the rest.

“I’m looking at the ’Net decidedly as an artform, because it seems to have no parameters whatsoever,” he continued. “It’s chaos, which I thrive on. But I do see opportunities, and I’m quite good at running with them, and I’m quite prepared to jump into just about everything . . . in the deep end.”

More fan encounters with the man in the street, in Paris (LEFT, 1999; © SIMONE METGE) and Dublin (RIGHT, 1997; © ALEX ALEXANDER).

BowieNet was to be “an environment where not just my fans, but all music lovers could be a part of the same community. A single place where the vast archives of music information could be accessed, views stated and ideas exchanged.”

Bowie spent the best part of a year overseeing the creation of BowieNet, in cahoots with William Zysblat (whose RZO organization was involved with the Bowie Bonds launch), Robert Goodale and Ron Roy, two veterans of the Internet and interactive technologies (Roy was project manager of the Cure’s official Web site).

Together they launched UltraStar Internet Services, a management/technology partnership whose first challenge, said Bowie, would be “to assemble unique proprietary content, along with first rate content suppliers and unparalleled Internet service from tech support to billing. After nine months of work, I believe we have achieved just that.”

Although BowieNet was to remain the most visible of Bowie’s Internet activities, his expansion into cyber-territory continued accordingly. A David Bowie Radio Network debuted via the Rolling Stone Radio Web site during 1999, and UltraStar quickly moved into arranging Web sites for other concerns. Several U.S. baseball teams were among the more headline-worthy entities to establish their own Web sites via what Bowie described as the “little generic ISPS” that UltraStar set up.

Online banking was next, as Bowie partnered with USABancShares.com to lend his name and face to checks, ATM cards and other products — the ultimate collectible for anybody who couldn’t get enough David Bowie.

The cynicism with which such activities were viewed was unbounded. In a world that had already enjoyed the antics of Richard Branson and Co., Bowie was not the first public personage to regard his notoriety as an eminently bankable proposition, in fields far beyond those for which he was renowned. Hitherto, however, such self-aggrandizement had been confined to businessmen: newspaper proprietors, record label chiefs, the heads of fashion houses.

Slowly, however, other entertainers joined the merry-go-round, and would continue to do so with ever grander consequences. When the footballer David Beckham joined Real Madrid from Manchester United in 2003, the Spanish side made no secret of the belief that they weren’t simply buying a player, they were also buying into a highly profitable brand name. And Iman’s personal cosmetics line would have been infinitely less profitable if she wasn’t already a world-famous model.

Exactly why rock ’n’ roll stars, alone of all entertainers, should seem morally prohibited from joining this particular gravy train is one of those cultural puzzles for which there is no real answer. The music’s rebel spirit has something to do with it, together with the belief that rock ’n’ roll, alone of all the modern arts, possesses the power to signally restructure society, whether across the entire spectrum of daily life, or merely within the hearts of its adherents.

But, truthfully, it was thirty years since that had truly been the case, with each successive rock revolution seeming ever more toothless, and ever more susceptible to the machinations of the wider media. Arguably, the punk rock of the late 1970s was the last musical movement to truly affect the way people saw things, and even that was basically confined to the UK. Post-punk, post-Live Aid, post everything the 1980s had wrought in their quest to fully submerge rock music within the world of mainstream entertainment, the opportunities for change, and the windows within which those opportunities flourished, grew ever more slender.

Was Bowie betraying the handful of slivers that still glistened as workable opportunities, then? Or was he acknowledging that some things are simply too entrenched to be altered, casting around for alternatives in places where nobody else might expect to find them? The Bowie Bank and the ISPS might not be the way to go. But, simply by establishing an almighty presence on the Internet, Bowie was confirming himself as one of the handful of people who could genuinely influence the way the medium developed over the decades to come. And, truthfully, who would one rather trust that particular future to? Bill Gates? The United States Congress? Or David Bowie?

Bowie did not wholly turn his back on his day job, as all these other opportunities cascaded around him. That same summer of 1998 he joined forces with producer Angelo Badalamenti to record a version of George Gershwin’s “A Foggy Day in London Town” for inclusion on the latest in the Gershwin-themed Red Hot And. . . benefit albums. A lovely version of a gorgeous song, a lyric that oozed thoughtful nostalgia around an arrangement that conjured up both fog and old London, the performance might have passed by many listeners unnoticed were it not for the sea change that it seems to have brought to Bowie’s own thought processes.

Orchestrated where he was accustomed to attack, moody where he preferred to melt down, “A Foggy Day in London Town” tapped deep into his sense of nostalgia, and provided an exquisite fanfare for Bowie’s next move, a reunion with someone who Bowie had known since the indeed foggy days in London, but with whom he’d not worked in some fifteen years — producer Tony Visconti.

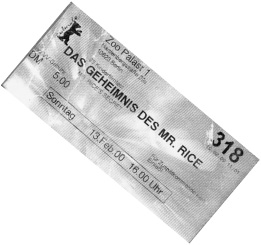

Signing and signed. Bowie defaces the back cover of Aladdin Sane outside the BBC Radio Theatre, June 27, 2000. (© DON ATKINS)

The pair had known one another since 1968. An expatriate New Yorker making his way through the music industry of London, Visconti was introduced to Bowie by music publisher David Platz, at a time when Bowie’s commercial star was as low as it could ever possibly sink, and he was essentially throwing every idea he could conceive into the marketplace, in the hope that one of them might stick. Platz himself warned Visconti, “no one knows what to do with him.”

Over the next three years, Visconti produced almost every one of Bowie’s new records; in fact, the only ones he didn’t handle were the monster hit “Space Oddity,” and the utter flop “Holy Holy.” Both the Man of Words / Man of Music and The Man Who Sold the World albums were Visconti jobs, though, and when Bowie needed a bass player for live work during 1970–1971, Visconti filled that role as well.

But then another of Visconti’s regular clients, Marc Bolan, began to take off, and, for three years more, those during which he himself grasped stardom, Bowie was forced to look elsewhere for a sympathetic ear in the studio. He found it in Ken Scott, and would not reunite with Visconti until 1974, when the American oversaw the mixing of Diamond Dogs.

On and off through the remainder of the decade, and unbroken between Low and the soundtrack for Baal, Bowie and Visconti represented one of the most formidably reliable studio teams of their generation. It is frequently forgotten that even the albums Bowie cut with Eno were Visconti productions.

Slowly, however, their relationship cooled, although Visconti himself was not aware of the fact until, having been told to keep the first months of 1983 free from any other engagements, he then discovered that he would be free from Bowie as well. The singer was off making Let’s Dance with Nile Rodgers, and the only person who didn’t know that was Tony Visconti.

Visconti put a brave face on the disappointment. “We’ve never had a cemented bond. We’ve always had an agreement that we’re free spirits.” He got on with his own career; he remained one of the era’s most in-demand producers, and one of the Bowie Universe’s most popular interviewees, happily agreeing to meet with various writers to reminisce warmly on the years he had spent with Bowie.

He spilled no beans, he dished no dirt, he was never less than truthful. But Bowie, so goes the legend, was first surprised, then annoyed, and finally positively vengeful at his old confidante’s volubility. Nobody ever said aloud that Visconti had talked his way out of producing another Bowie record, and the possibility of them working together seems never to have arisen. But, when it did become public knowledge that Bowie and Visconti were reuniting to record a song for the forthcoming Rugrats movie, the phrase “patched up their differences” was the description of choice.

“Bowie is very, very private,” explained one of his latter-day associates, “and he expects his friends and collaborators to be aware of that. If he feels they aren’t, if they say too much in interviews . . . or even agree to be interviewed without clearing it with him . . . then he starts to wonder what else they aren’t aware of, until finally, he just cuts off all contact with them.”

Was that what happened to Visconti? Nobody knows for sure. But Visconti himself dropped a major hint when he acknowledged that he had certainly learned something from the severance: “how sensitive he is about his privacy. I’ve learned to respect that . . . . It was only in very recent years, around the time he made contact again, that I realized how much I missed him. We had both grown and changed, so the time was right to open the channels again.”

It was Bowie himself who made the call that reunited the old friends. He and Gabrels had already worked out an arrangement for the Rugrats song, “(Safe in the) Sky Line,” but with the movie producers demanding that his contribution be cast firmly in the mould of the “classic Bowie sound,” as Visconti put it, a little bit “Space Oddity,” a little bit “‘Heroes,’” a little bit “Absolute Beginners,” it only seemed natural to get in touch with the man who helped cast at least one third of that sainted triptych.

With Bowie and Gabrels joined in the studio by the Bongos’ Richard Barone, former Blondie drummer Clem Burke, Prefab Sprout’s Jordan Rudess and a twenty-four-piece string section, “(Safe in the) Sky Line” was recorded in August 1998. Then the Bowie-Visconti team moved straight into another project, recording a version of John Lennon’s “Mother” for inclusion on the Lennon tribute album planned by Yoko Ono to mark what would have been the slain Beatle’s sixtieth birthday in October 2000. (Other contributions to the project included Sinéad O’Connor’s take on “Mind Games,” Paula Cole’s “Working Class Hero” and Everclear’s “Instant Karma.”)

In the end, neither Bowie song would see the light of day. The Lennon tribute remains “forthcoming” all these years later, while the Rugrats contribution was cast aside when the scene it accompanied was cut from the movie. Karen Rachtman, the film’s music coordinator mourned: “I have always wanted to work with David Bowie and I finally had my chance. He delivered a song far beyond my wildest dreams and now I can’t even use it. The song is beautiful.”

For Bowie, however, the time spent on the two tracks was valuable in its own right. Both sessions, he said, offered “a good excuse for [Tony and I] to get back into the studio.” He acknowledged that they discussed recording an entire album together, but decided on a more cautious approach to begin with. “We didn’t want to run the risk of doing a whole album, and then discovering after three songs that there was no more current between us. And it worked very well, to the point that we are going to work together in the near future.”

With so much going on, the one blow to the spiraling expansion of David Bowie as a multimedia business empire came with Virgin’s rejection of the Earthling Live tapes, a decision that effectively dismantled his own (largely unannounced) plans for the remainder of 1998, as he found himself instead needing to plan for another new album altogether.

No matter that the label’s relationship with virtually every other “veteran” act on their books, from The Sex Pistols to the Rolling Stones, revolved around pumping out interminable concert souvenirs. No matter that the Bowie discs would celebrate his most critically acclaimed concerts in twenty years — not since the days of Station to Station, in 1976, had a David Bowie tour received such glowing praise as this one. The live album was canned.

For Gabrels, Bowie’s decision to return to the studio could not have been more welcome. Disappointed that so much work had gone to waste earlier in the year, he was nevertheless confident that Bowie would now accede to the most obvious notion, that Earthling deserved a followup “in the same way Aladdin Sane followed Ziggy. . . an extrapolation of the previous album. The music had evolved, the band was playing great.”

Bowie took one look at such logic and vowed to wander off in another direction altogether, flying Gabrels alone out to Bermuda with him, to begin planning not simply a record, but the one that the pair might have made together a full decade earlier, before Tin Machine weighed in to the scene. “We [will be] recording most of the stuff ourselves,” Bowie explained. “Reeves and I playing most of the instruments and programming drums, etc.” Other musicians would be invited along if they were required. For the most part, however, the pair would record the new album in much the same way as Bowie and Iggy Pop cut The Idiot, “two old ladies with knitting needles,” as Iggy once put it.

It was a decision that thoroughly derailed Gabrels’ hopes of recording a new album with the Earthling combo, in that it sidelined both Gail Ann Dorsey and Zachary Alford. But it was also a dream come true, a chance to finally undertake the full-on collaborative effort they’d spent so long talking about.

With no more accompaniment than they could wring from guitar and keyboards, the pair began piling up material. If their activities could be compared to any aspect of Bowie’s past, it was surely the air of unrestrained creativity that haunted his roost at Hadden Hall, Beckenham, in the very early 1970s, as he and Mick Ronson strummed and plonked their way toward Hunky Dory. Indeed, as word of Bowie and Gabrels’ activities began to get around, that album became the yardstick by which this new effort would be measured, a hope that Visconti, once he’d been given the chance to digest the new music, was not to discourage.

“[Bowie’s] songwriting has returned to that more melodic sound with accessible lyrics,” he applauded. The “weirded-out Bowie,” patiently constructing incomprehensible sentences and cutups with his computers, was far from view; instead there lurked “beautiful lyrics about relationships and life experiences and, like in the 1960s, a vast sonic panorama.”

Bowie agreed at least with the gist of that summation. “There was very little experimentation in the studio. A lot of it was just straightforward songwriting. I enjoy that; I still like working that way.” By the new year, he estimated that he and Gabrels had written close to 100 songs for the project, and almost every one was acoustic. “I think you’ll be surprised at the intimacy of it all.”

Not all of the songs were intended for Bowie’s own use. Gabrels, too, was planning a new solo album — his first since The Sacred Squall of Now — and songs that didn’t initially appear to fit the David Bowie mold were laid aside for his own use: “Survive,” “We All Go Through,” “Jewel,” “The Pretty Things Are Going to Hell.”

Another conduit for the duo’s creativity appeared when they were approached to contribute a soundtrack to a new computer game, Omikron: The Nomad Soul. Designed by the same team that created the mega-selling Tomb Raider, Omikron was a magnificent construct in which gameplay was almost secondary to the situation in which it is set, a vast cityscape within which the player can become literally lost, simply poking into corners, and looking into stores.

Bowie marveled that there were 200 hours of exploring to be done in the city alone, and, even more than the game, “[that was] the more interesting factor for me. Not only do you get your own apartment, you can also go shopping, buy records . . . I don’t bother with the game, I just live in the city. The cool thing is, you can actually take a virtual leak in the bathroom, which is unheard of! You can do virtually anything.” You could even go to see Bowie himself playing live. The Dreamers — Bowie, Gabrels and Gail Ann Dorsey — were a regular bar band in Omikron City.

According to the game’s designer, David Cage, “Bowie was really involved in the game development. The process of getting him on board and working with him has been much easier than anybody can imagine. I think that we met at the right moment, as Bowie was really looking for a project like [this], with solid art and designs, deep content and strong technology. Technology used in the game allows us to have real actor performances in real-time 3D, and tell a real story.” Plus, he concluded, “I think that Bowie took on enough different personas in the past to know better than anybody how it feels to be someone else.”

The material that Bowie and Gabrels were writing in Bermuda lent itself ideally to Bowie’s vision of the game. “My priority in writing music for Omikron was to give it an emotional subtext,” he explained; an escape from the stereotypical electro-Industrial clatter that accompanies most computer games.

Cage agreed. “The last thing we wanted on the game was video game graphics or video game music. We succeeded in having unusual visuals for a game, and Bowie and Reeves made unusual music.”

Four untitled instrumentals were laid down for the set, together with a clutch of finished songs. For a short time, the prospect of Bowie and Gabrels serving up no less than three albums worth of new material, side by side, was mouthwatering, even before they themselves addressed that issue. As time passed, however, a somewhat different scenario began to emerge.