2

SEVEN CITIES OF GOLD

In 1937, a man by the name of Milton Ernest “Doc” Noss was hunting in the Hembrillo Basin area of New Mexico. He is said to have climbed a small rock outcropping less than 500 feet high and sat down, scanning the area for a deer to shoot. When he sat down, he noticed air coming from a hole beneath the rock he was sitting on. He moved the rock and found the entrance to a cave that is said to have held treasure worth over $3 billion.

While exploring the cave, Doc is said to have found chests full of coins and jewels, saddle bags, over 16,000 bars of gold weighing over 40 pounds each, Wells Fargo boxes, and letters, the most recent dated 1880. According to Kathy Weiser, writing on the Legends of America website, Doc and his wife, Ova “Babe” Noss, “spent every free moment exploring the tunnels inside the mountain, living in a tent at the base of the peak. On each trip, Doc would retrieve two gold bars and as many artifacts as he could carry. At one time, he brought out a crown, which contained two hundred forty-three diamonds and one pigeon-blood ruby. . . . Among the artifacts, Doc is reported to have retrieved were documents dated 1797, which he buried in a Wells Fargo chest along with various other treasures. Although the originals have never been recovered, a copy of one of the documents proved to be a translation from Pope Pius III.”1 In addition to all the treasures mentioned above, Doc is also said to have found numerous swords and twenty-seven skeletons. Some of the skeletons were still bound and tied to the floor inside the tunnel-cavern complex.

Most accounts of this story agree that in 1939, in efforts to expand the narrow passageways of the cavern, Doc made a terrible mistake. He used dynamite, and in doing so collapsed his only known way into the cavern. It’s said that he buried much of the gold he recovered in various places around the desert and that because gold was illegal for civilians to own at the time, he tried to make contacts with dealers in the black market. It is also said he became increasingly paranoid and trusted no one. He left his wife, married another woman, drank more, and in 1949, he was shot in the back of the head by one of his business partners.

Doc’s former wife, Ova Noss, never gave up trying to recover the treasure from Victorio Peak, but her efforts were greatly hampered when the government decided to extend the boundaries of the White Sands Missile Range in 1955.

An article from the Los Angeles Times reports that “in 1958, four airmen from nearby Holloman Air Force Base, including Thomas Berlett, spent several months excavating at the site and claim they discovered stacks of gold bars in several caverns. They took nothing, and tried to get permission to recover the treasure.”2

The four airmen are said to have passed polygraph tests given to them in the early 1960s by the Air Force and the Secret Service. They were given permission to return to Victorio Peak but claimed they couldn’t find their way back into the caverns, because they had dynamited the entrance to prevent others from gaining access. They were later ordered to keep away from the site. People claimed the Army had gone in and removed the treasure; while the Army had admitted to being there, they denied finding any treasure.

While I don’t doubt most of the Noss story or the account of the four airmen, parts of the story raise some big questions. Victorio Peak’s namesake, for example. It gets its name from Chief Victorio, an Apache chief, who, some historians claim, placed the treasure deep inside the mountain. He is said to have obtained the treasure from robbing and pillaging. But 16,000 bars of gold weighing over 40 pounds each? Approximately 320 tons of gold from robbing and pillaging in the American Southwest? That seems highly unlikely.

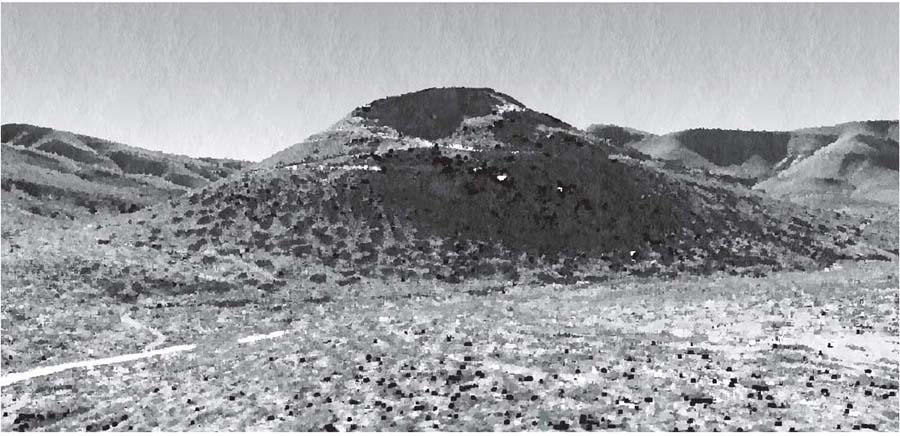

Fig. 2.1. Victorio Peak, New Mexico

To put 320 tons of gold into perspective, let’s compare the amount of gold the Spanish acquired from the New World to the 320 tons of gold allegedly stashed inside Victorio Peak by Chief Victorio. “Between 1500 and 1650 the Spanish shipped from America to Europe about 181 tons of gold and 16,000 tons of silver.”3 I seriously doubt that one man and his band of warriors could rob almost twice as much gold in less than 30 years than armies from Spain did in 150 years.

That said, I also doubt that this was a KGC treasure. If the KGC had known about the treasure in Victorio Peak, and if their goal was to fund a second Civil War, then it only makes sense that they would have seized the opportunity to use the funds from Victorio Peak and gone to war. Precious metals are weighted according to a unit of measure referred to as troy weights, which are said to have originated in Troyes, France, during the Middle Ages. One troy pound of gold is equal to 14.5833 ounces instead of 16 ounces. In terms of tons, it depends on whether we’re dealing with short, long, or metrictons. In trying to keep this simple, I’ll just go with a short ton, which weighs less than the long and metric tons. Three hundred and twenty short tons of gold at approximately 29,166 ounces per ton, priced in 1863 at $30 per ounce, would bring the treasure to a value of around $279 million. Having other large treasures hidden away, the KGC would have had more than enough gold to feed, clothe, and arm a sizeable force for several years.

Then there’s the letter Doc Noss is said to have reburied in a Wells Fargo chest. The letter was dated 1797, with a translation from a text by Pope Pius III. That too throws doubt on this being a KGC treasure. The translation from Pope Pius III, who held the papacy for an extremely brief period from September 22, 1503 until October 18, 1503, states the following: “Seven is the Holy number,” the passage begins. It then continues for several lines before ending with a cryptic message. “In seven languages, seven signs, and languages in seven foreign nations, look for the Seven Cities of Gold. Seventy miles north of El Paso del Norte in the seventh peak, Soledad, these cities have seven sealed doors, three sealed toward the rising of the Sol sun, three sealed toward the setting of the Sol sun, one deep within Casa del Cueva de Oro, at high noon. Receive health, wealth, and honor.”4 Soledad is said to have been the former name of the peak known as Victorio Peak, and Casa del Cueva de Oro is Spanish for house of the golden cave. If that is true, then it sounds as if Doc Noss stumbled upon at least part of the treasure of Cibola.

That brings up another issue. Researching the legend of Cibola, the Seven Cities of Gold, it is claimed that the legend began with a slave by the name of Estebanico (also spelled Estevanico) who was a part of the Narváez Expedition, which began in 1527. While the expedition was in what is now Texas, they were given a baby rattle made of copper and were told stories of wealthy cities to the north. After the expedition ended, Spanish Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza “dispatched the Franciscan Monk Marcos de Niza to investigate,” according to an article on the Ancient History Encyclopedia website, which continues:

Nizas’ guide was this Estebanico: Being a survivor of the previous expedition he was believed to be knowledgeable about the lay of the land. Described as a “Black Muslim from Azamoor” (a coastal city in northwestern Morocco), he was an intelligent, educated man and most likely spoke several languages.

In his diary, Friar di Niza noted his disgust of Estebanico by stating he had acquired, “great stores of turquoise and other wealth, as well as many native women.” Despondent and angry, Estebanico originally stayed well ahead of the group but as his relationship with Friar di Niza worsened, he stayed so far ahead of the main party their only communication was by a message tied to a cross. It was on one of these messages that Estebanico said he had heard of seven great cities to the north. The people were very wealthy, he wrote, with multi-storey [sic] buildings and fine cotton clothes. Estebanico called these cities Cibola. This was the last message they received from Estebanico as a short time later, the party were told he met the Zuni Indians and they killed him.5

The Narváez Expedition started in 1527, and Estebanico was said to have been killed in 1539. Pope Pius III died in 1503, thirty-six years before the legend of Cibola is said to have begun. Either the story of the letter dated 1797 and containing the translation of Pope Pius III is a hoax or the story regarding the beginnings of the legend of Cibola is wrong. Digging deeper, I found what is said by some to be the origins of the legend of Cibola.

The origins of the legend of Cibola began when the Moors invaded Porto, Spain, in the eighth century. Seven bishops in the city gathered all the wealth and fled westward to the Atlantic, to an island called Antilla. When the New World was discovered, many believed they had found Antilla. Bishops, being a part of the church, would have very likely sent word of their departure to others, and this could explain how Pope Pius III came to know about it.

Based on the information I had read, I doubted the treasure was placed there by Chief Victorio or the Knights of the Golden Circle. The Spanish explorers allegedly did not know about it until they heard tales from the native peoples, yet Pope Pius III is said to have written about it sometime before his death in 1503; if so, he may have known of this because of the seven bishops who fled Spain in the eighth century. There are just too many unanswered questions regarding this treasure and whom it belonged to. We know the airmen passed their polygraph tests, and that backs up the stories and witness accounts of the treasures found by Doc Noss, so the evidence that a treasure was found appears to be sound. What doesn’t add up are the theories of where the treasure came from. There are other theories as well; like those mentioned above, they left me with more questions than answers.

The lure of the treasure in Victorio Peak is so great that mention of it even appeared in the Watergate hearings in 1973: “John Dean, the former lawyer for President Richard M. Nixon, mentioned that Attorney General John Mitchell had been asked to pull strings to allow some searchers to look for the gold.”6 Former New Mexico Attorney General David Norvell summed it up well when he stated, “There’s too much evidence to discount completely the possibility that there’s something still in there.”7

I had yet to find a connection between this treasure and the KGC template, but I was not giving up, and I continued searching for other known treasures. Researching the next location would lead to information that continues to amaze me to this day.