7

GATES OF LIGHT

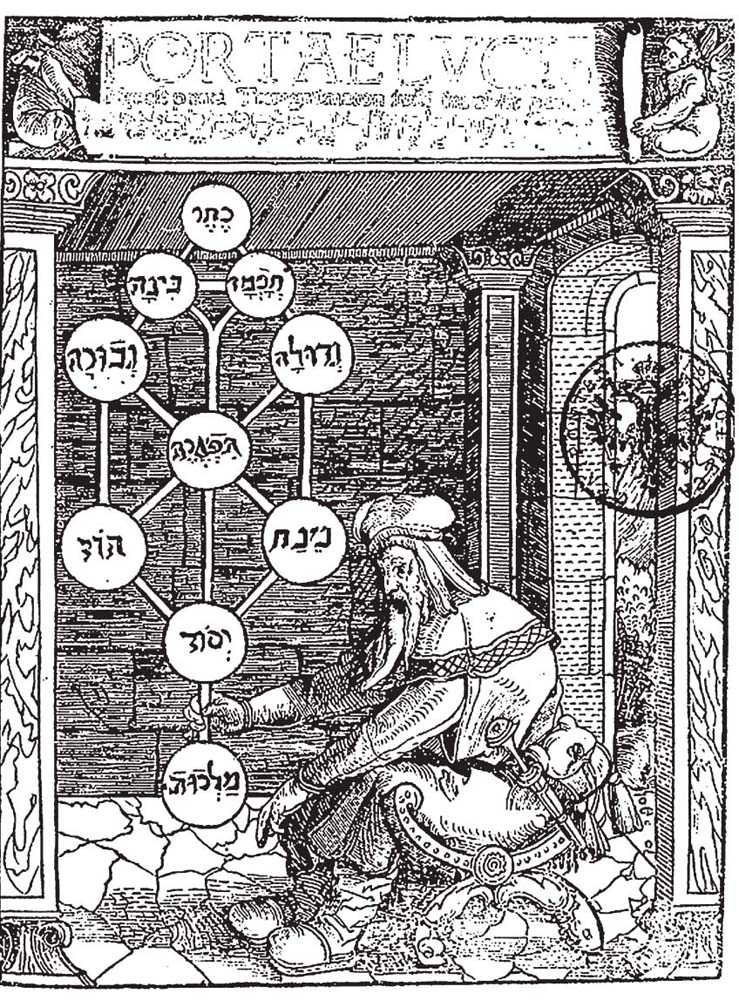

In 1516, a man by the name of Paolo Riccio, also known as Paulus Riccius, published a book titled Portae Lucis, which translates into English as Gates of Light. The illustration on the frontispiece of this book is said to be the first time that a diagram of the Tree of Life was reproduced for a public audience (see fig. 7.1 below). The book is a translation of a work by Rabbi Joseph ben Abraham Gikatilla (1248–ca. 1325) and can currently be viewed online at Austrian Literature Online, a website operated by the University of Innsbruck, Austria.

Paolo Riccio was a Jewish convert to Catholicism, a student of Christian Kabbalah, and a professor at the University of Pavia in Italy, and he served as physician to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I. “Riccio relates that he was ordered by Emperor Maximilian to prepare a Latin translation of the Talmud. All that has come down of it are the translations of the tractates Berakot, Sanhedrin, and Makkot (Augsburg, 1519), which are the earliest Latin renderings of the Mishnah known to bibliographers.”1

The fact that a Tree of Life was published prior to the birth of Francis Bacon was not an issue; on its own, that would have had no effect on my theory. What did affect some portions of my theory were parts of the illustration surrounding the Tree of Life. The illustration contains several symbols and includes what I believe could be a map.

Fig. 7.1. The frontispiece of Portae Lucis, 1516.

Apart from the Tree of Life in the illustration above, which is a little different in shape than most Trees seen today, I immediately noticed the crisscross design of what I have come to refer to as the Veil. The man is most likely a Jewish rabbi and appears to be wearing heavy boots, gloves, and a pack, and is armed with a short sword or dagger. Since the book is a translation of a work by Gikatilla, I would assume that the man in the illustration would be Gikatilla himself. He is dressed for traveling, which could possibly serve as a symbol for traveling the spiritual path of the Tree of Life. The hashmarks on the wall behind the man could very well be a representation of rain, which is often seen as a blessing. (I might not have pieced together the rain symbolism in the Portae Lucis map without the modern music video titled “Victoria Hanna–The Aleph-bet song (Hosha’ana)” on YouTube.)

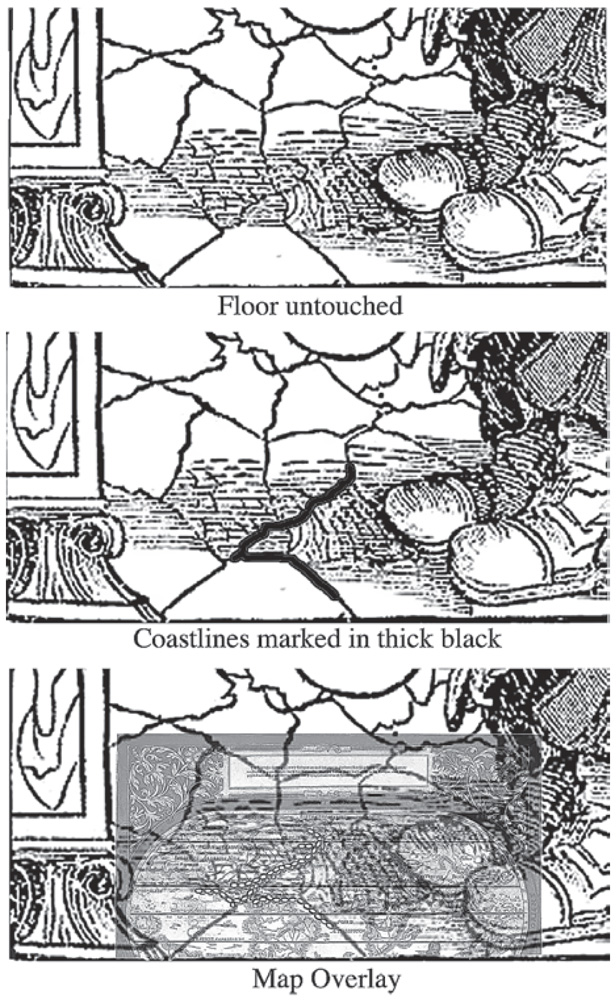

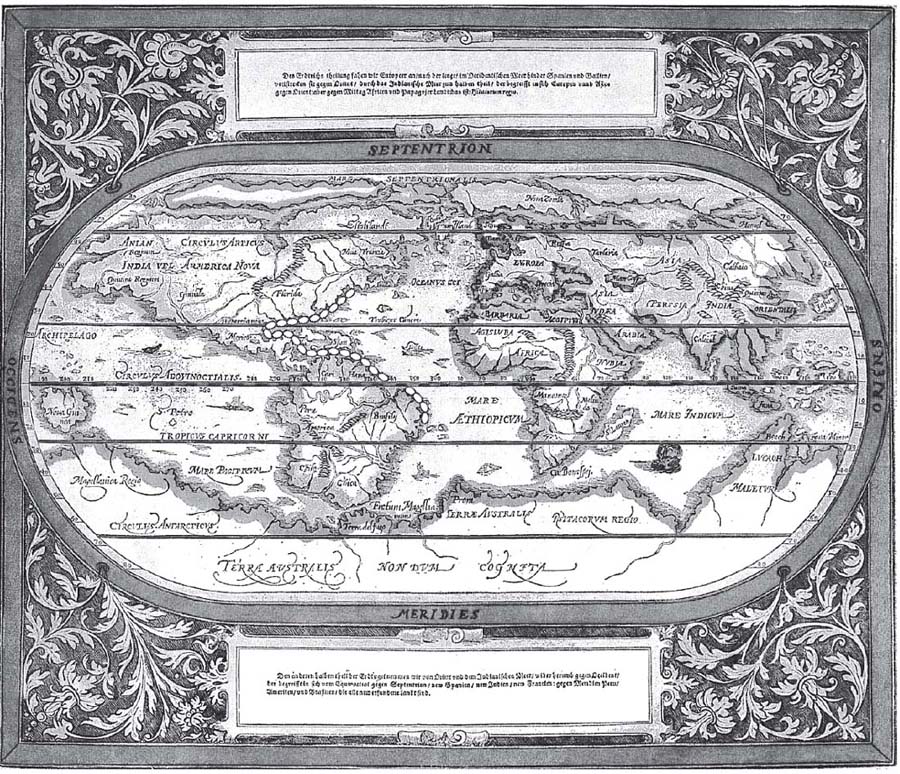

The man in the illustration is pointing at his boots. Directly in front of his boots appear to be ripples in water, as if he is on one side, facing in the direction of the water, and on the other side of the water are more tiles. The shape of the tiles on the other side of the ripples looked vaguely familiar to me. I had a hunch, so I searched for a sixteenth-century world map and overlaid it on the illustration from Portae Lucis. To say that I was amazed was an understatement. When I overlaid the illustration with a map from 1544, the area below the Tree of Life on the drawing matched the shape of the Atlantic Ocean and the eastern coastline of the United States, as well as the coastlines of Mexico, Central America, and parts of South America! It isn’t perfect, but it is very close, and it is certainly close enough to convey a message.

Fig. 7.2. Hidden map in illustration from Portae Lucis

Fig. 7.3. World map published by German cartographer Sebastian Munster in 1544

Now this could mean a couple of things. It could fall in line with the Tree of Life template I had discovered, and if that was the case, it wasn’t Francis Bacon and his peers who came up with the Tree of Life template, but someone before them. It could also mean the New World offered opportunities for people, including Jews, who for centuries had suffered under inquisitions, discrimination, and harassment throughout Europe. It could have held out a branch of hope for those living an almost hellish, uncertain life in Europe. There are no words that come close to describing the horrors they went through. As Edward Kritzler describes in his book Jewish Pirates of the Caribbean: “When Spain’s Monarchs banished the Jews to purify their nation, followers of the Law of Moses sailed with the explorers and marched with the conquistadors. With the discovery and settlement of the New World, they took solace in the hope of finding a safe haven, or at least putting distance between themselves and the Inquisition.”2

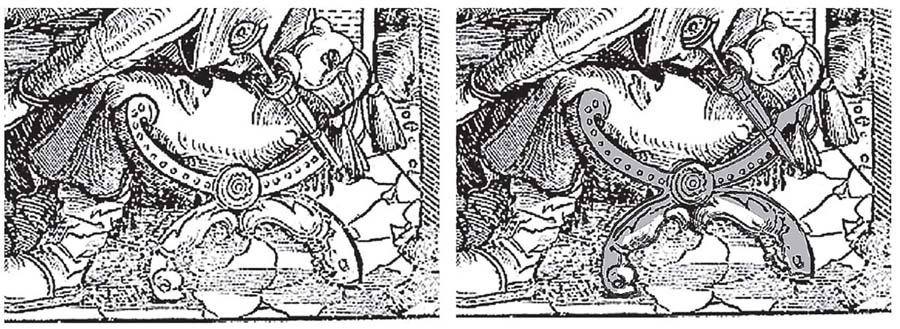

Everything about that illustration can be viewed as relating to the Tree of Life template, but on the same note, everything about that illustration can be viewed as relating to Jews looking for a safe haven. There is, however, one more symbol in this illustration that tips the scales in favor of the Tree of Life template. That symbol comes in the form of what forensic geologist, author, and host of the History Channel’s H2 program America Unearthed Scott Wolter has described as a hooked X symbol. In the illustration from Portae Lucis, the X is the chair the man is seated on, and his short sword or dagger serves as the hook (see fig. 7.4 below). If this is indeed a hooked X symbol, then that could tie the treasure of the Veil and Tree of Life to the Knights Templar. In fact, the Veil template marks a location very near the site where the Kensington Runestone was discovered.

Fig. 7.4. The hooked X symbol on the drawing from Portae Lucis

The Kensington Runestone, discovered near Kensington, Minnesota, has been a topic of debate since the time it was discovered in 1898. Some claim it is a hoax, while others have gone through great lengths to show that it is indeed legitimate. On the stone can be found ancient runes, among which is a hooked X symbol. This hooked X symbol got Scott Wolter started on his trail of discoveries: he wanted to know if the stone was a hoax or if it was authentic. After determining the stone’s authenticity, he went on to several other discoveries, linking the hooked X symbol to Christopher Columbus, the St. Clair family of Rosslyn Chapel in Scotland, and the Knights Templar.

Now we have more puzzling questions. If this does have some kind of Templar connection, why would Paolo Riccio, a Jewish convert to Catholicism, have anything to do with it, especially two hundred years after the Templars were destroyed by a deeply indebted king of France and the Catholic church?

In searching for answers, I decided to start from yet another angle. The first template I worked with, the Veil template, has a unique shape. I had already gone over the numbers and shape of that template, interpreting the circle and square as a joining of the Heavens and Earth, male and female, but I wanted to take another look at it in regard to religious structures. What did I know about the Templars and Jews other than that they had been treated with extreme prejudice by the Catholic church? What, if anything, stood out in regard to religion or religious structures? Could I find anything that would connect or tie in with the Veil template? After much more research, I finally found an answer, or at least a very good clue.

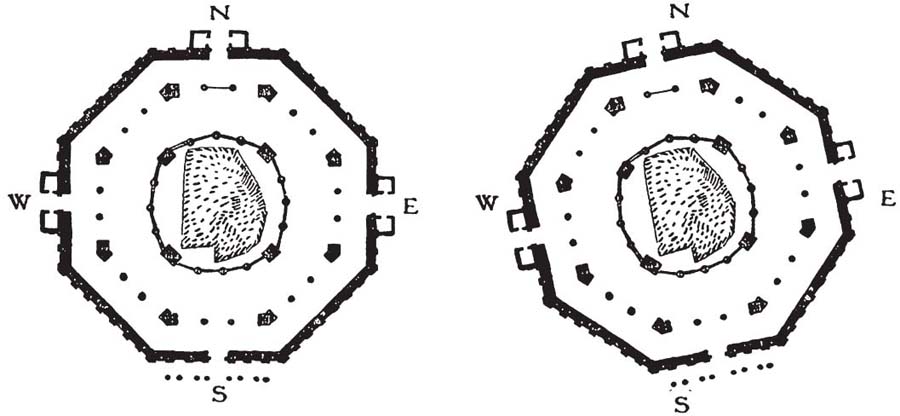

The first temple in Jerusalem was on the Temple Mount, and on the Temple Mount today is the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque. Looking at the design of the Veil template or an individual cell of the template, I found its design was almost identical to the design of the Dome of the Rock (see fig. 7.5 below).

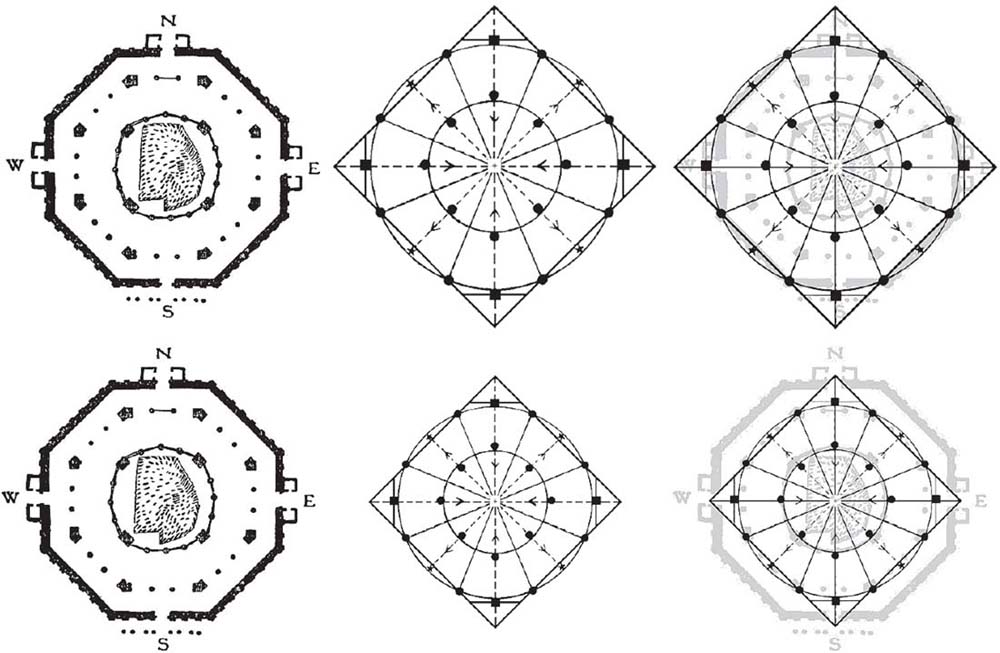

I found a nice diagram of the layout of the Dome of the Rock in a book by W. R. Lethaby titled Architecture, Mysticism, and Myth, published in 1892. I added the template and then the Dome of the Rock layout, with an overlay of the template. I first lined up the template with the outer edges of the octagonal walls of the Dome of the Rock, but the fit wasn’t quite right; however, as you can see on my second attempt from left to right across the bottom of the illustration, the inner and outer circles match the inner and outer circles within the confines of the Dome of the Rock.

Fig. 7.5. Dome of the Rock with Template overlay

One thing I found wrong with Lethaby’s illustration was in the compass bearings he used. The Dome of the Rock isn’t oriented like that, and neither is the large Veil template; they are both turned a few degrees west of north, that is, counterclockwise, which is referred to as the “occult pole” by some. Figure 7.6 gives a better description of the actual orientation.

If the Templars were involved in the Tree of Life and Veil templates, why pattern the template after the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem? The Knights Templar were there, and they, like many Jews, Christians, and Muslims today, considered it one of the holiest sites in the world: “The Knights Templar, active from c. 1119, identified the Dome of the Rock as the site of the Temple of Solomon and set up their headquarters in the Al-Aqsa Mosque adjacent to the Dome for much of the 12th century. The Templum Domini, as they called the Dome of the Rock, featured on the official seals of the Order’s Grand Masters (such as Everard des Barres and Renaud de Vichiers), and soon became the model for round Templar churches across Europe.”3

Fig. 7.6. Dome of the Rock: Lethaby’s diagram is on the left; the actual orientation of the Dome is on the right.

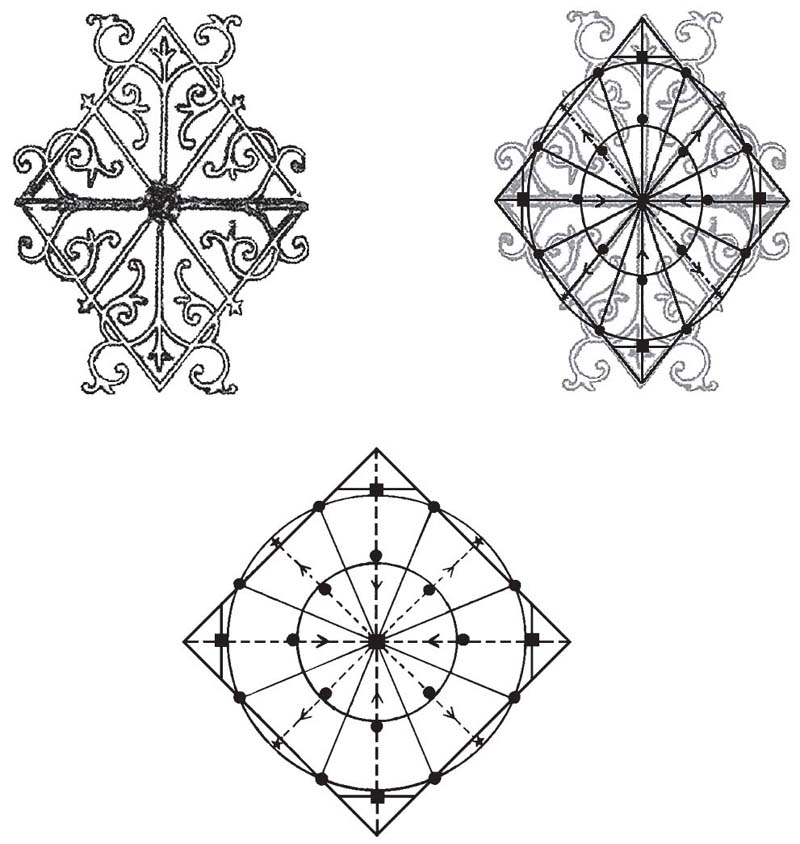

One of the best-known round Templar churches is the Temple Church in London, built by the Templars in 1186. It’s a beautiful building, full of history, but what really caught my eye was a design on a door on its western side (see fig. 7.7 below).

It’s not an exact match, but it is very close. Instead of a square, the Temple Church design is a diamond shape (rhombus), and the inner circle isn’t visible unless we use a little imagination and notice that the scrollwork on the inside hints at the presence of the inner circle. This is very similar to the template and fits the scale. Like most symbols, it could convey a message to those in the know without giving away the secret.

We have the Veil template matching the design of the Dome of the Rock, and it also matches well with a design on the door of a Templar church. We have the Tree of Life from the frontispiece of an early sixteenth-century book in conjunction with a hidden map of the New World, and a hooked X symbol, which has been traced to the Knights Templar by forensic geologist Scott Wolter. But we need more.

Fig. 7.7. Design from a door of the Temple Church (top left) with template overlay (top right). The template itself is at the bottom.

What I did not have at the time were the names of people showing a line of succession back to known Knights Templar.