Practice Test 2:

Answers and Explanations

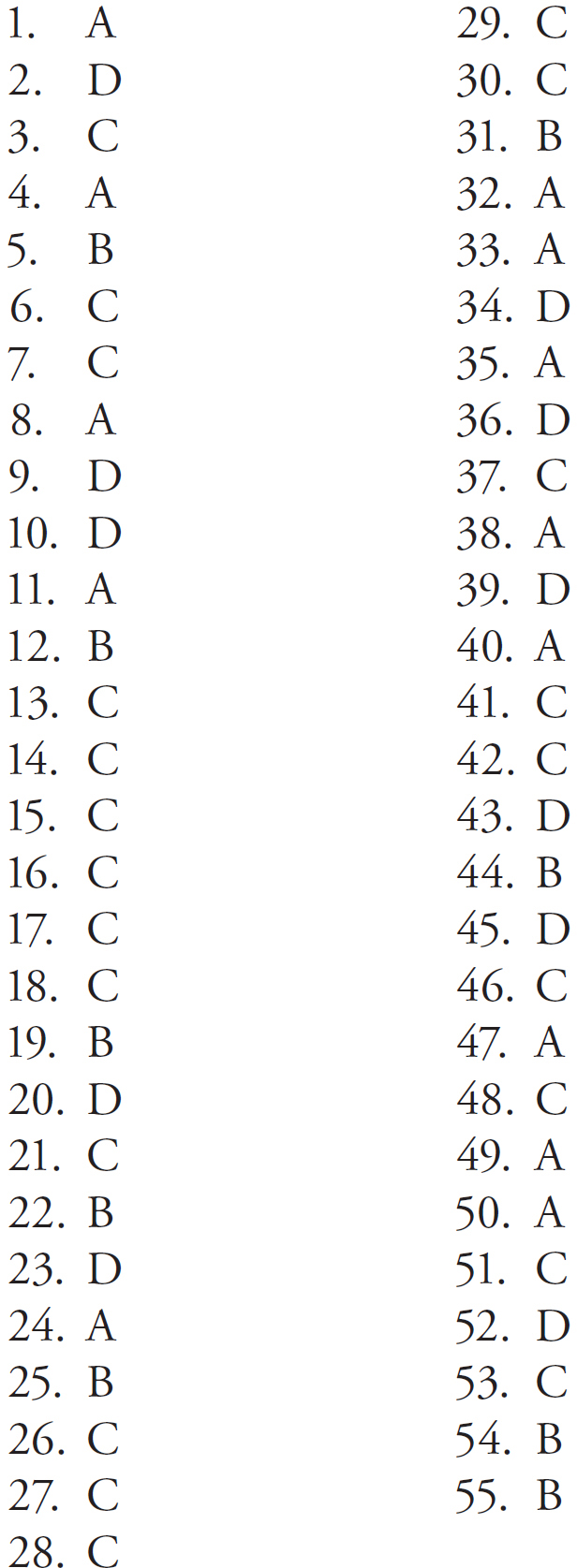

PRACTICE TEST 2 ANSWER KEY

PRACTICE TEST 2: ANSWERS AND EXPLANATIONS

Section I, Part A: Multiple Choice

1. A

Innovation has become an accepted and desired part of life, but it wasn’t always so. The world of tradition transformed itself in the last years of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, when massive world wars, radical scientific discoveries, and an utterly changed standard of living for all European people resulted in a new philosophy. Russell was radical in one other respect; he was one of Europe’s first atheists as well.

2. D

The phrase “knowledge of antiquity” should’ve clued you into the right answer. Neoplatonism developed concurrently with Renaissance humanism, but it was different—a mystical theology based on The One (think The Matrix), nous, the world-soul, numerology, and celestial hierarchy. None of this is covered by Renaissance humanism. Neoclassicism was an 18th-century movement, and scholasticism was medieval.

3. C

The text states that there was an emphasis on the relative importance of Plato as opposed to Aristotle. Such conversation, as well as the bridging of Eastern European and Western European cultures at the Council of Ferrera, created a venue for the Greek classics to enter the minds of Western Europeans. Therefore, the correct answer is (C).

4. A

According to the text, the “substitution of Plato for the scholastic Aristotle was hastened by contact with Byzantine scholarship.” Therefore, you should look for an answer that brings Plato to Italian culture. Italian Renaissance author Pico della Mirandola’s Oration on the Dignity of Man provides a Platonic view of humanity by highlighting the potential of man. This is a perfect example of the cultural diffusion described by Bertrand Russell. The correct answer is (A).

5. B

Process of Elimination combined with some test-taking logic should tell you that the other answers are unsupported. A glance at the tables tells you that, materially, the Allied forces outweighed the German forces in every possible way. The word perhaps in (B) also tells you that it’s a good answer—the College Board does love a good weasel word, signifying possibility, but not certainty.

6. C

Bombers were long-distance military planes. Given the distance from the U.S. to Europe—as well as the distance from our bases to various locations in the Pacific theater—it would be logical that the U.S. forces might have many more of those.

7. C

Choice (A) is the trap. While the Soviets had an enormous military, they didn’t quite have the same production capabilities as the United States. Furthermore, they didn’t participate in D-Day, busy as they were with their own eastern front battle against the German menace.

8. A

The most straightforward way to determine which German and Allied units are most closely matched is to look at the ratios in the tables. The ratio of Allied to German ground troops is 1.43 to 1. This is closer than the ratio for tanks (3.93 to 1), artillery (1.5 to 1), and air force (7.4 to 1).

9. D

It is clear from the table that Germany lagged far behind the Allies in terms of air force production. This data is consistent with the idea that German production lines did not keep up with the needs of the generals. Choice (D) is correct.

10. D

During World War I, the German populace experienced rationing, the entrance of women into the factories (to replace the men who were called to duty), and much propaganda urging them to fight for their country. English citizens experienced all of these things, too. Total war, however, did not mean the total annihilation of all citizens of your opponent’s country. While civilians were certainly killed, the primary aim of military attacks remained enlisted personnel and centers of production.

11. A

The cartoon depicts the German kaiser using all possible resources, including people, to win the Great War. (Remember to pay attention to the caption! This goes for any image on the exam that is accompanied by text.) This idea is referred to as “total war.” In order to mobilize all resources, governments took control of certain industries. This action set the precedent in a number of countries for government regulation of industry—even during peacetime.

12. B

Because the cartoon is a commentary on the concept of total war, you should think about total war’s consequences. One is that industries must focus their resources on winning the war and not necessarily domestic concerns. It was not uncommon for food shortages to arise on the home front due to this temporary change in priorities. Choice (B) is the answer.

13. C

The cartoon offers a critical view of the kaiser’s commitment to total war. This is perhaps due to the fact that the creator of the cartoon is British, which matches (C). The clue here is the caption—Punch magazine was a famous British satirical publication, which suggests the nationality of the artist.

14. C

Indicating that he would use his people dead or alive is not a ringing endorsement for the kaiser’s sense of empathy. The cartoon clearly intends to criticize this callous indifference, which aligns with (C).

15. C

The philosophy of mercantilism went through many phases, one of which was an early, primitive form known as bullionism. This holds one simple tenet—the more specie (gold and silver) your society possesses, the wealthier your society will be. This describes 16th-century Spain quite well. However, while this may seem superficially true, it doesn’t take into account important variables such as productivity, favorable balance-of-trade, individual rights, and so on.

16. C

High inflation was caused by the influx of gold and silver from the Spanish treasure fleet from the New World, especially the silver from Potosí, Bolivia. Basically, there were too many people with too much money chasing too few goods. While inflation has been a fact of life in the West for many decades, even centuries, back then it was a shockingly new phenomenon, and the poor felt even poorer as they could no longer afford to purchase goods.

17. C

This question requires you to have some knowledge about the individual goals and motivations of explorers during the Age of Exploration. According to the text, Cortés is motivated by the acquisition of gold. A similar motivation drove Pizzaro, (C), to South America and into the Incan Empire. The primary goal of Columbus, da Gama, and Dias was to find better routes for the spice trade.

18. C

Hernán Cortés had briefly owned an encomienda in Hispañiola, but really is noted for conquering the Aztec Empire in modern-day Mexico. There is no other option that relates to his life. Be sure to associate Pizarro with Incas, Cabral with Brazil, Diaz with the Cape of Good Hope, da Gama with India, and Magellan with circumnavigation.

19. B

Given the vast amounts of land in South America, Central America, and the Caribbean, there was hardly any shortage of land. Most encomiendas were assigned to former conquistadores as the Spanish crown’s way of both rewarding their loyalty (despite being essentially mass murderers) and organizing the people in newly conquered lands. Interestingly, though, the Spanish crown never intended them to be permanent, and by the end of the century had assumed direct control over the encomiendas.

20. D

England, as the most advanced representative democracy in Europe, the first to convert to a constitutional monarchy, took the lead in decentralizing political authority. While there was still a king and queen, there had also been a prime minister since the early 19th century. Most other European countries retained harsher forms of centralized authority, and thus handicapped their own success.

21. C

The title of the cartoon, “The Devilfish in Egyptian Waters,” should indicate that it is referencing an event that took place in Egypt. This should eliminate (B) and (D), which involve Fashoda (in Eastern Africa) and Russia, respectively. This leaves (A) and (C), which both have to do with the Suez Canal. After the Suez Canal was completed in 1882, the British created a protectorate in Egypt to defend its pathway to its colonial holdings in India, which aligns with (C). The Suez Crisis, (A), refers to an event that took place much later, during the Cold War.

22. B

If you remember that the Primrose League advocated for British imperialism, then you should have guessed that they would not be happy with a cartoon such as this, since it portrays imperial Great Britain as a menacing creature. The correct answer is (B).

23. D

All of the countries listed in the answer choices except for Germany, (D), had significant imperial holdings. Germany, as you should recall, abstained from the imperial game due to Otto von Bismarck’s indifference. He found European dominance much more appealing than imperialism.

24. A

As an old saying goes, “the sun never sets on the British Empire.” Great Britain had secured imperial holdings all over the globe, from India to Australia to Boersland (South Africa). Therefore, you can eliminate (B) and (C). The cartoon provides no evidence of countries either resisting or not resisting Imperial Britain, so (D) cannot be correct. The fact that the sea creature is holding on to Ireland should point you to (A).

25. B

The word bourgeois, as well as the phrase “You will never be happy as long as you own anything” should’ve clued you in that the author is referring to redistribution of wealth via socialist means.

26. C

The Congress of Vienna had existed to reorganize and stabilize Europe after the fall of Napoleon. Headed by Metternich, it was profoundly conservative by nature. That’s a pretty far cry from anarchy.

27. C

Communism primarily was concerned with overturning the traditional owner/employee model of societal organization. You could make the argument that capitalism also cares about its workers, but only indirectly, given the invisible hand theory, and that a rising tide lifts all boats.

28. C

The steam engine operated more efficiently on coal than on wood, and so with its invention, a new industry was created—coal mining. There were massive deposits in England, France, and Poland, and going down into the mines became the primary way for working-class people to make a living.

29. C

Class struggle was on everybody’s minds in the late 19th century owing to Marx and Engels. Noblesse oblige was a traditional way of taking care of the poorest in society, but that had been rejected a hundred years earlier. Choices (A) and (B) are off topic.

30. C

Even though there are many similarities between Erasmus and Martin Luther, both of whom criticized the Catholic Church, the focus in this particular text is on Erasmus’s ability to bring Latin and classical culture to the masses. The key sentence is at the end of the first paragraph: “He familiarized a much wider circle than the earlier humanists had reached with the spirit of antiquity.” In this regard, Erasmus is quite similar to Francisco Petrarch, whose fascination with classical culture inspired the civic humanists. Therefore, the answer is (C).

31. B

When humanism ceased to be the exclusive privilege of the few, people could study the Latin Bible as well as ancient texts of the classical era. This newfound knowledge would eventually enable people to begin questioning the laws and interpretations of the Catholic Church. Thus, (B) is the answer.

32. A

As a product of the 20th century, the author has consciously or unconsciously adopted the biases of his age, which includes a predilection for universal education and openness to various different points of view.

33. A

In the passage, Huizinga writes, “Erasmus introduced the classic spirit, in so far as it could be reflected in the soul of a 16th-century Christian, among the people.” It is evident that Erasmus understood classical texts to be consistent with his religion. Similarly, the Neoplatonists endeavored to use Platonic texts to better understand Christianity, making (A) the correct answer.

34. D

According to Huizinga, “Until this time the humanists had…monopolized the treasures of classical culture.” However, he then goes on to contrast these humanists with Erasmus, who had “an irresistible need of teaching.” This indicates that, unlike earlier humanists, Erasmus made it a priority to spread his knowledge of classical culture. This best aligns with (D), which is the correct answer.

35. A

The social reformers of the Victorian era were largely middle-class Christian women who decided that the lower classes lacked moral instruction, which alone would improve their lives. You can argue whether or not this was exactly true, but nonetheless it was in line with Biblical teachings. It also reflected a new class-consciousness in England, as the middle class had ballooned to a previously unknown size and strength.

36. D

The title Gin Lane, along with the destitute people pictured in the engraving, indicate that this piece of art comments on the problems associated with alcohol consumption. Since “spirits” refers to liquor, (D) is correct. Even if you have never heard of the Sale of Spirits Act, close analysis of the engraving coupled with Process of Elimination should help you get rid of the other answer choices, which have nothing to do with alcohol or destitution.

37. C

Use question 35 to help you here, which established that the artist uses deliberate exaggeration for effect in this engraving. Deliberate exaggeration as an artistic device points to the piece’s satirical purpose, which aligns with (C).

38. A

The crowded city scene depicted in the engraving should bring to mind the Enclosure Acts, (A), which forced farmers off their lands and into the cities, resulting in overcrowding. This accelerated during the Industrial Revolution, as machines, rather than people, became a cheaper way for landowners to produce crops.

39. D

Similar to what happened in the realm of science, 20th-century European art was marked by the rejection of pretty much every aspect of traditional art up until that time. This includes recognizable human figures, evident character, and attention to minute details. However, since Hogarth’s work wasn’t portraiture, (D) isn’t applicable.

40. A

Indeed, by this time in English history, the monarchy was well on its way toward becoming a titular head-of-state. The power of Parliament had already been well established, and the office of the prime minister had become (in the persons of Disraeli and Gladstone) a new center of political power.

41. C

The Tories were (and are) one of England’s political parties, which hints at the idea of democracy and greater egalitarianism. This transition had occurred back in the turbulent 17th century, as the members of the famous Stuart dynasty struggled with the rise of representative democracy. This ultimately ended with the forcible abdication of James II, and the official creation by William and Mary of a constitutional monarchy.

42. C

For outrageous behavior amongst nobility, nobody can beat the French under Louis XIV. A quick tour of the pleasure grounds at Versailles will show you how vain, pompous, self-absorbed, and weak the nobility had become under his reign. That was all by design, of course. Distracting the nobles with endless free parties allowed Louis XIV to assume power in their neglected states, which contributed to his absolute power.

43. D

There is nothing in this letter as ordinary—and, you could say, as touching—as when the queen complains of her exhaustion. We’ve all felt tired. Modern historians, and modern entertainment, have seized upon the “ordinary lives of the powerful” meme for quite a while. It’s a sign of the deeply egalitarian nature of our current society.

44. B

With Britain enduring no military attacks from mainland Europe during this time period, and with the British Empire growing rapidly overseas, you can eliminate (C) and (D). There was a potato famine in 1845, but it was in Ireland, not England, so eliminate (A). You’re left with the truth—in her 64-year reign, Queen Victoria had to navigate through an equally unprecedented number of changes to English society.

45. D

At the conference at Yalta, Roosevelt and Churchill divided Germany into four zones—U.S., English, French, and Soviet. Since the Soviets had marched into the country from the East, it made sense that they would control that portion. This was the beginning of East Germany and the Iron Curtain, and it marks the first formal postwar expansion of their land.

46. C

Eastern European countries such as Yugoslavia and Hungary joined the Warsaw Pact, (C), an organization created as a direct answer to NATO. The Warsaw Pact was in part a Soviet military reaction to the integration of West Germany into NATO in 1955, but it was primarily motivated by Soviet desires to maintain control over military forces in Central and Eastern Europe.

47. A

As indicated by the bottom map, while Eastern Europe fell under Soviet influence, Austria held its own (it is the lighter shade of gray). This observation is consistent with (A), as it suggests that Austria was able to resist Stalin. Since command economies are characteristic of communist systems, there is no evidence that Finland (also shaded the lighter gray on the map) had such an economy. Eliminate (B). Unlike the other Balkan countries on the map, Greece is a lighter shade of gray, so (C) can be eliminated. Choice (D) is also incorrect, as Czechoslovakia fell under Soviet influence (it is dark gray on the map) and therefore it’s unlikely that it was able to maintain a free economy.

48. C

Soviet tactics during World War II included rolling across Polish land, destroying its people, murdering 15,000 Polish officers in a forest (see Katyn massacre), and generally behaving even worse than the Germans that were occupying the country. No Pole would support these methods.

49. A

Although West Berlin, entrenched in East Germany, was technically a part of West Germany, West Berlin was not the capital. The capital of West Germany was actually Bonn, a city firmly situated in West Germany. Therefore, the answer is (A).

50. A

Northern European churches did not place the same emphasis on art as did southern European churches. Therefore, churches in the Netherlands did not commission artists to create works. However, the Netherlands in the 17th century was a wealthy place. Private collectors were able to support the artists directly, so Dutch homes were not uncommon places to see art on display. The correct answer is therefore (A).

51. C

Process of Elimination should help you choose the correct answer. Since the Dutch were dominant in trade in the 17th century, (D) should have stood out to you as being possibly true. The Netherlands was a haven of religious tolerance; indeed, the Puritans who first settled America spent several years in the Netherlands preparing for their journey. Thus, (B) can be eliminated. You should vaguely associate the Netherlands with windmills, so you can get rid of (A) as well. Choice (C) is the answer.

52. D

The focus on the ancient world is more characteristic of the Italian Renaissance, so eliminate (A). Royalty commissioned art and thus increasingly became the subject of artwork when absolute monarchs began to rise, which is a bit later in European history than when this painting was created. Eliminate (B). The Dutch were not particularly concerned with religious imagery in art, so (C) does not work here. The mundane scene depicted in the painting should point you to (D), everyday life.

53. C

The arrival of empiricism was the hallmark of the scientific era. Francis Bacon was one of its earliest proponents, and the book that this passage is taken from, Novum Organum, was his attempt to unseat Aristotle, whose body of work was called the Organon. It was intended to be a catalog of everything that could be sensed. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he never finished it.

54. B

The Aristotlean worldview had been rediscovered by Italian traders as they entered into Arabic lands. This sparked the accomplishments of the Renaissance. However, the scientists of the time considered ancient natural science to be antiquated and irrational, and a poor method of searching for truth. Therefore, the answer here is (B).

55. B

The entire scientific explosion of the late 19th century—all the plodding laboratory work that was performed by Pasteur, Curie, and hundreds of other famous names—was based upon a belief in empirical thought. While (D) may have been tempting, the common person doesn’t generally look for new organizing principles for life.

Section I, Part B: Short Answer

Question 1

Pinpoint the years from around 1760 to 1820 on the graph to locate the First Industrial Revolution, and 1840 to the late 19th century for the Second Industrial Revolution to get a sense of the impact those revolutions had. Similarities abound between the two industrial revolutions, and you could’ve included any of the following:

-

rapid technological advances

-

First revolution: Mention Richard Arkwright, flying shuttle, spinning jenny, etc.

-

Second revolution: steam engine, railroads, Henry Bessemer, etc.

-

-

peasantry divorced from agriculture

-

increased production, as evidenced by the graph

-

continued rise of the merchant class

-

improved health outcomes due to increased food production and medical innovations, as evidenced by the life expectancy data

Differences include any of the following:

-

The Enclosure Acts and the putting-out system (or cottage industry) occurred in the first revolution. The peasants were reduced to doing piecework in their huts.

-

The second revolution, by contrast, saw the massive movement of peasants into cities, and the beginning of work in factories.

Question 2

The first three thinkers (Locke, Hobbes, Smith) are most likely to be chosen to be representative of Enlightenment thought. Descartes is most likely not to represent Enlightenment thought, but you can make a case for Hobbes or Hume too. Here is a checklist of things you should’ve mentioned for each:

-

Locke: strong individual = little government needed. The right to private property is sacred, tabula rasa, Second Treatise on Government.

-

Hobbes: weak individual = strong government needed. Leviathan. Life in a state of nature is nasty, brutish, and short.

-

Smith: invisible hand of the market guides society, laissez faire, Wealth of Nations.

-

Descartes: deductive reasoning, mind/body split, systematic doubt, “I think; therefore, I am.”

-

David Hume: empiricism, radical rejection of all religion, relentless systematic doubt, sensory experience is everything, early psychologist.

Question 3

You should remember that the Council of Trent was part of the 16th-century Counter-Reformation. It was the official dogmatic response to the Reformation.

-

Part (a): Any of the famous Protestant Reformer figures would be appropriate here, including Desiderius Erasmus, Jan Hus, Martin Luther, Huldrych Zwingli, John Calvin, Thomas Cranmer, William Tyndale, and others.

-

Part (b): The Counter-Reformation had three components: the Council of Trent (which cannot be used, since it is the provided source material), the Spanish Inquisition, the Index of banned books, and the establishment of the Jesuit order as a manner of promoting good Catholic behavior to the world.

Question 4

The Holy Roman Empire was a loose, multiethnic conglomeration of principalities that existed from the early Middle Ages until its dissolution in the early 1800s. The questions zero in precisely on the religious history.

-

Part (a): The religious conflict in general that gripped all of northern Europe in the 1500s was obviously the Protestant Reformation. You could’ve mentioned this alone, or you could’ve been more specific, discussing many of the figures mentioned above in part (a) of question 3. You also could’ve brought in specific events such as the 95 Theses, the Diet of Worms, the Bibles printed in vernacular, or the Peace of Augsburg.

-

Part (b): After 1600, there’s really only one major event in European religious history: the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648). It devastated the Holy Roman Empire, both financially and politically, and left the territory divided into a Protestant north and Catholic south.

Section II, Part A: Document-Based Question (DBQ)

The Document-Based Question (DBQ) section begins with a suggested 15-minute reading period. During these 15 minutes, you’ll want to do the following: (1) come up with some information not included in the given documents (your outside knowledge) to include in your essay, (2) get an overview of what each document means and the perspective of each author, (3) decide what opinion you are going to argue, and (4) write an outline of your essay.

This DBQ deals with the issue of Chartism and is asking you to determine whether Chartism should be viewed as a revolutionary movement or as a moderate movement. You will need to have some knowledge of British politics in the 19th century to handle this question and at least a little familiarity with Chartism, although don’t be too concerned if your knowledge of Chartism is somewhat limited.

The first thing you want to do, BEFORE YOU LOOK AT THE DOCUMENTS, is to brainstorm for a minute or two. Try to list everything you know (from class or leisure reading or informational television programs) about both Chartism and British politics in the first half of the 19th century. This list will serve as your reference to the outside information you must provide to earn a top grade.

Next, read over the documents. As you read them, take notes in the margins and underline those passages that you are certain you are going to use in your essay. Make note of the opinions and position of the document’s author. If a document reminds you of a piece of outside information, add that information to your brainstorming list. If you cannot make sense of a document or it argues strongly against your position, relax! You do not need to mention every document to score well on the DBQ.

Here is what you might see in the time you have to look over the documents.

The Documents

Document 1

This first document lays out the six points of the Charter. They are as follows:

1. universal suffrage

2. no property requirement for Members of Parliament

3. annual parliaments

4. equal representation (meaning that all areas of the nation would be equally represented)

5. payment of Members

6. vote by secret ballot

You’ll notice that the document refers to the idea of the Charter providing for the “just representation of the people of Great Britain…,” an indication that the goal is the political inclusion of working-class individuals rather than the complete overhaul of the system.

Document 2

This excerpt from a speech by J.R. Stephens given at a Chartist rally addresses one of the central issues behind the rise of Chartism. For Stephens, the Charter is all about providing people with the basic needs of life such as food and shelter. As a Chartist, Stephens believed that political rights were the means for British workers to achieve a better standard of living.

Document 3

This article, which appeared in a Chartist newspaper, appears to be aimed at those Chartists who were advocating the need for armed violence. While implying that it is within an Englishman’s right to rebel and is, in fact, “the last remedy known to the Constitution,” the article strongly rejects the use of physical force as an option in the current situation.

Interestingly, one of the arguments against the use of arms has little to do with morality and everything to do with the potential for success. The author points out that to succeed, armed revolts would have to be staged concurrently throughout the land, and that even if they are staged concurrently there would still be only a “slender chance” for success. Perhaps reluctantly, the author does concede that those who have arms should hold onto them, although they should be used only in self-defense.

Document 4

This document is a poem in honor of Feargus O’Connor. Besides noticing how nicely everything rhymes, you should be aware that the document refers to the earlier imprisonment of O’Connor, who, at the time the poem appeared in print, was free to continue with his labors on behalf of the Chartists.

Document 5

Document 5 contains a portion of a newspaper article detailing the events at a Chartist social gathering. It is important to note that the gathering consists of a tea party and ball, activities that clearly imitate the social activities of the upper classes and appear far from revolutionary. Feargus O’Connor (the same individual lionized in Document 4) was unable to attend the tea party because he and some of the other Chartists were busy debating whether to call for a general strike (certainly not many middle-class tea parties were interrupted for similar reasons).

Document 6

While male Chartists split over the question of whether the right to vote should be extended to women, women were actively engaged in the Chartist movement, both as a source of support for male Chartists and as active participants in their own right. This document, from a female Chartist organization, should be viewed in conjunction with Document 2, because, like the earlier document, it focuses on the economic hardships of working-class life, rather than placing a specific emphasis on the political struggle or women’s rights within the Chartist movement.

Document 7

Make note that the author of this letter is a middle-class man and that the letter reveals some of the fears that his class must have felt about a working-class movement that they neither understood nor sympathized with. Also, the source for his information is the Times, the most important newspaper of the establishment and again not necessarily a source for genuine understanding of the Chartist movement.

Outside Information

We have already discussed much more than you could possibly write in only 45 minutes. Don’t worry. You will not be expected to mention everything or even most of what we have covered in the section above. You will, however, be expected to include some outside information, that is, information not mentioned directly in the documents. The following is some outside information you might have used in your essay.

-

The ostensible goal of Chartism was the passage of the “People’s Charter,” a document that called for universal suffrage for all men over the age of twenty-one, the end of property requirements for those holding seats in Parliament, annual parliamentary elections, equal electoral districts, and payment of those holding seats in Parliament. Chartists organized massive petitions that were presented on several occasions to the House of Commons, although the House of Commons did nothing to act on them. The largest and final petition was presented in 1848 with around 3 million signers.

-

Five of the demands of the Chartists are today a part of the British constitution. The only one that has never been enacted was the idea of annual parliamentary elections, a radical idea that went back to the constitutional struggles of the 17th century. Today the maximum life of a parliament is five years thanks to the Fixed-Term Parliaments Act of 2011. Before the passage of this act, Parliament could be dissolved only by royal proclamation. The changes enacted in 2011 were part of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition agreement which was produced after the 2010 general election.

-

The late 1830s and the 1840s were a particularly difficult period, one known to historians as the “hungry forties.” Economic difficulties may account for the rise of Chartism, particularly if the movement is viewed as one whose primary goal was the establishment of political rights for working-class individuals so that they could have some say over the economic conditions that ruled their lives. Economic conditions may also account for the decline of Chartism after 1848, since these were years of growing economic prosperity and therefore may have led to an easing of political demands.

-

Working-class individuals were angered over the passage of the Great Reform Bill (1832), which provided political rights for middle-class individuals, but ignored the rights of the working class. Additionally, there was a tremendous amount of working-class frustration with certain bills passed by this new “reformed” Parliament, including the 1834 Poor Law, which treated those suffering from poverty with great harshness.

-

1848 was a year of revolutionary activity throughout Europe. In France, the monarchy was replaced by a republic and revolutions spread across Europe. You should know from your studies of this period, however, that England and Russia were the two European states that were exempt from revolutionary activity in that year.

-

There were two dominant factions within Chartism. The majority can be labeled “moral force” Chartists; they wanted to peacefully campaign for the passage of the “People’s Charter.” “Physical force” Chartists were a smaller faction found primarily in the cities of Northern England; they advocated the possible use of violence should their demands not be met. William Lovell was the leader of the moral force Chartists, while Feargus O’Connor was the main figure in the opposing faction.

-

Chartism as a movement declined rapidly in the years after 1848. Working-class men increasingly looked to labor unions as a source for economic change rather than mass political movements, though working-class political activity did not disappear. The British political system would prove to be more flexible than many had imagined, and in 1867 male working-class householders received the vote, while in 1884 their counterparts in the countryside received the same.

Choosing a Thesis Statement

This DBQ is asking you to take sides in a debate. On the basis of the documents, a much stronger case could be provided for taking the position that Chartism should be viewed as a movement for political change that was not fundamentally revolutionary. Keep in mind that while there are strong historical arguments for taking the other side (and a number of books and articles have taken the position that Chartism was inherently revolutionary), you must base your argument primarily on the documents provided on the exam. The documents provided truly lean toward the nonrevolutionary aspects of the movement. Your thesis statement could be as follows: Though it inspired passion among both upper and lower classes in England, Chartism was undoubtedly a nonrevolutionary movement.

Planning Your Essay

Unless you read extremely quickly, you probably will not have time to write a detailed outline for your essay during the 15-minute reading period. However, it is worth taking several minutes to jot down a loose structure of your essay because it will actually save you time when you write. First, decide on your thesis and write it down in the test booklet. (There is usually some blank space below the documents.) Then, take a minute or two to brainstorm all the points you might put in your essay. Choose the strongest points and number them in the order you plan to present them. Lastly, note which documents and outside information you plan to use in conjunction with each point. If you organize your essay in advance of writing, the actual writing process will go much more smoothly. More important, you will not write yourself into a corner, suddenly finding yourself making a point you cannot support or heading toward a weak conclusion (or worse still, no conclusion at all).

For example, to deal with the issue of whether Chartism was revolutionary you might want to organize a brainstorm list like the following:

Political demands of the Chartists

Six points of the Charter

Economic issues

Chartism and women

Violence and nonviolence

Hunger

Actions taken by the Chartists

End result of Chartist activities

Next, you would want to figure out which of your brainstorm ideas could be the main idea of paragraph number one, which ones could be used as evidence to support a point, and which should be eliminated. You should probably begin your first paragraph with your thesis, and then discuss the specific political demands of the Chartists in an attempt to show that the Chartists were interested in being included in the British political system and were not seeking its destruction. You should mark the paragraph topic with a 1 to show that it’s the theme of your first paragraph; then get more specific with a note if it’s supporting evidence. In this case, your list might look like this:

Political demands of the Chartists: 1

Six points of the Charter: 1-evidence

Economic issues

Chartism and women

Violence and nonviolence

Hunger

Actions taken by the Chartists

End result of Chartist activities

If paragraph one is going to deal with the political demands of Chartism, you should certainly refer to Document 1 because it lays out the Chartist program. You might want to use your second paragraph to deal with the economic issues behind Chartism. This approach is a way to show that economic deprivation played a major role in leading working-class individuals toward political activity, not for the purposes of destroying British society, but to ensure that there was food on their tables. You could therefore make use of Documents 2 and 6, both of which deal with the economic deprivations behind Chartism. In this case your list would look like this:

Political demands of the Chartists: 1

Six points of the Charter: 1-evidence

Economic issues: 2

Chartism and women: 2-evidence

Violence and nonviolence

Hunger: 2-evidence

Actions taken by the Chartists

End result of Chartist activities

Proceed in this way until you have finished planning your strategy. Try to fit as many of the documents into your argument as you can, but do not stretch too far to fit one in. Don’t be concerned, for example, if you can’t find a use for the poem in honor of Feargus O’Connor. An obvious, desperate stretch will only hurt your grade. Also, remember that history is often intricate and that the readers of your exam want to see that you respect the intrinsic complexity behind many historical events.

Section II, Part B: Long Essay

Because you only have 40 minutes to plan and write this essay, you will not have time to work out elaborate arguments. That’s okay; nobody is expecting you to read two questions, choose one, remember all the pertinent facts about the subject, formulate a brilliant thesis, and then write a perfect essay. Here are the steps you should follow. First, choose your question, brainstorm for two or three minutes, and edit your brainstorm ideas. Then, number the points you are going to include in your essay in the order you plan to present them. Finally, think of a simple thesis statement that allows you to discuss the points your essay will make.

Question 2—Enlightened Absolutism (Option 1)

Question 2: Compare the extent to which the term “enlightened absolutism” applied to certain rulers in Eastern Europe and Russia during the 18th century.

About the Structure of Your Essay

In this essay, you will want to make a strong thesis statement, perhaps arguing that while those rulers who are labeled as “enlightened absolutists” often spoke about enlightened ideas, for the most part they failed to implement any substantive changes within their realms. On the other hand, you could list some of their actual achievements (such as in the area of religious toleration), while pointing out that powerful elements within their states such as the Church or nobility blocked any possibility for further reform. Most importantly, be sure to compare rulers of different countries and draw connections among them. The question makes it clear that comparison is the historical thinking skill you are being tested on.

Your essay should mention at least some of the following:

-

Most of the leading writers of the Enlightenment, such as Voltaire and Diderot, wanted change to come about not through the advent of republics, but rather through “enlightened monarchs” who would seek to reform their ideas based on the concepts of enlightened reason.

-

The monarchs whom historians are mostly referring to when using the term “Enlightened Absolutists” are Catherine the Great, the empress of Russia (1762–1796); Joseph II of Austria (1741–1790); and Frederick the Great, the King of Prussia (1740–1786).

-

These Enlightened Absolutists certainly read the works of the leading writers of the Enlightenment. Frederick read Voltaire and was so impressed that he invited him to stay at his court. Catherine also read Voltaire, as well as Diderot, and when Diderot desperately needed money to get out of debt, Catherine bought his extensive library and then generously lent it back to him.

-

Joseph of Austria was influenced by the Enlightenment’s call for religious toleration. Joseph granted Jews the right to worship (though they had to pay special taxes for the privilege), while Protestants were given the right to hold positions at the court in Vienna. That spirit of tolerance didn’t extend to all Enlightened Absolutists, as Frederick refused to grant similar rights to the Jews of his realm and Catherine did nothing to grant rights to religious minorities in Russia.

-

Writers of the Enlightenment had discussed the need for humane treatment for the accused. Both Joseph and Frederick banned the use of judicial torture within their realms, while Frederick went so far as to ban capital punishment. Both rulers also relaxed the strict censorship that existed in their states, although at times they still banned works they considered critical of their rule.

-

All three enlightened monarchs attempted to expand the number of individuals receiving an education, not so as to create freethinkers, but rather that they might have more trained individuals to serve as bureaucrats. Although none of the states implemented anything close to universal public education, they did greatly increase the number of individuals who went to school. These students, however, almost exclusively came from the higher classes.

-

Frederick, in his youth, had toyed with the concept of enlightened statecraft based on just relations among states. However, when he saw the opportunity, he launched an unprovoked attack on the Habsburg territory of Silesia.

-

Joseph of Austria ended the practice of owning serfs, although the newly freed peasants found that freedom came with the price of greatly increased taxes. Joseph discovered that further reform in the countryside was impossible due to the strong resistance of the nobility.

-

None of these rulers took steps toward making their states constitutional monarchies. Catherine toyed with the idea of granting a constitution, but in the end, she and her fellow absolutists showed little interest in doing anything that would place actual limits on their power.

Question 3—Domestic Tensions on the Eve of World War I (Option 2)

Question 3: Compare the domestic problems faced by TWO of the great European powers in the decade immediately prior to the outbreak of the First World War.

About the Structure of Your Essay

The years immediately prior to World War I were notable for the domestic problems faced by the great powers: Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia, France, Italy, and Great Britain. Since the question is asking you to deal with two of these states, it would be to your advantage to quickly consider a list of domestic concerns for each of these states and then decide which two states on your list look most promising when it comes to writing your actual essay. Like Question 2, this question requires you to compare the domestic problems of two countries, so be sure to draw explicit connections between them in the text of your essay.

Depending on which two nations you decide to focus on, your essay might mention some of the following points:

-

On the surface, Germany was the great behemoth of Europe, possessing the strongest army, a growing navy, and an unmatched industrial base. Despite these apparent strengths, on the eve of the First World War, Germany was facing a potential political crisis, with more than one nationalistic politician stating that Germany needed a “blood cure” (war) to divert public attention. The constitution that Bismarck established for the new German state in 1871 did not create a constitutional monarchy along British lines. While the national Parliament, the Reichstag, was elected by universal male suffrage, its powers were severely restricted. The chief minister of the state, the chancellor, was selected by the kaiser and not dependent upon the support of the Reichstag.

Despite being in many ways a conservative, militaristic society, Germany also had the largest Socialist party in all of Europe, and the Socialists were the single largest political party in the Reichstag by 1912. The problem was that while the party could bring hundreds of thousands of people out in the street for demonstrations and garner around a third of the popular vote, by itself it could not enact desperately needed political reform. The party rejected the revisionist Socialist views of Eduard Bernstein, who argued that a socialist state could be achieved without a violent revolution. Yet, the S. P. D., while clinging to revolutionary rhetoric, became a parliamentary party rather than a revolutionary one. Kaiser Wilhelm, however, remained convinced that the party was committed to the destruction of his state and lived in dread of the eventual day when the Socialists would put their revolutionary rhetoric into action.

German Liberals, who perhaps should have been the leaders of the move to a genuine parliamentary system, found themselves split among a number of splinter parties as they argued over issues such as protective tariffs. Meanwhile, in the decade before the war, the right witnessed a surge in small parties that espoused beliefs that foreshadowed the program of the Nazi party.

Germany faced other domestic problems on the eve of the war. Many Germans bemoaned the declining world of the independent farmers, who were being crushed by a decline in food prices, and of craftsmen, who were threatened by the rise of large industry. Small shopkeepers also were threatened by large department stores. All of these problems contributed to the rise of anti-Semitic parties, which deflected blame from the government and encouraged Germans to blame the negative changes that were coming to their lives on Jewish retailers and bankers. While not as considerable as that facing Austria-Hungary, Germany had its own nationality problem with many voicing concern that Polish families were buying farmland from impoverished Prussian Junkers, while the higher birthrate among Polish families portended a potential population explosion in the east. Meanwhile in Alsace and Lorraine, territories that Germany had seized as part of their victory in the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, a population that was ostensibly ethnically German would have preferred to substitute French rule for that of the heavy-handed Germans.

-

In Austria-Hungary, the Emperor Franz-Joseph saw himself as the father of his people, but he couldn’t have been a proud parent when considering the behavior of his “children.” The emperor saw his throne as being above the nationality problem and to some extent affection for the emperor made this true. However, the aging Franz-Joseph (he was born in 1830) couldn’t live forever, and there was a sense that his demise would soon be followed by the collapse of his empire. The establishment of the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary in 1867 had not solved the nationality problem and, in some ways, had made it worse as other nationalities strove to match the status achieved by the Hungarians. Within Hungary, the Magyars, who made up half of the population, essentially ignored minority rights. With only five percent of the male population in Hungary allowed to vote, Magyar magnates controlled a political machine that ensured their dominance over the political and cultural life in the Hungarian kingdom. While there were those within the empire who were advocates of breaking the empire into a federation of nationalities, the grim reality in Hungary revealed that this would not solve the problem since each federation would have had its own nationality problem. The nationality question dominated all other issues within the empire and right on the eve of the war there was a major political problem in Bohemia over the question of whether to teach German or Czech in the public schools.

While the army and civil service were two institutions that were reasonably successful in providing some sense of common imperial identity, other attempts to match this success failed. Universal male suffrage, adopted in 1907, led to even greater conflict in the Austrian Parliament, the Reichsrat, as each nationality was represented by its various partisans. The institution itself was to become infamous for the unbelievably poor behavior of the parliamentary representatives as they cursed, threw things, and spit on their rivals. Eventually this tentative experiment in parliamentary rule was deemed a failure, and the emperor shut down the Parliament at the beginning of the war.

Of all the seemingly implacable problems facing Austria-Hungary, it was the South Slav issue that was most pressing on the eve of the First World War. The establishment of an independent Serbian state in 1878 out of a former piece of the Ottoman Empire was not a major problem for Austria-Hungary except for the fact that it was a state built on the issue of nationality, in this case, a Serbian national identity. At the same time the Serbian state was born, Austria-Hungary took administrative control over the province of Bosnia, a territory that had a significant ethnic Serbian population. Relations between the two states were amicable until 1903 when the pro-Austrian Serbian dynasty was replaced by a group of army officers who wished to see Serbia pursue a more nationalistic program and ally themselves with their fellow Slavs in Russia. Ensuing tensions between Austria-Hungary and Serbia led to the so-called “Pig War,” an economic war in which Austria-Hungary refused to import Serbia’s main export—pigs. In 1908, Austria-Hungary broke an earlier promise it had made to Russia and formally incorporated Bosnia into the empire. This step was undertaken not out of a desire to add more Slavs to their already polyglot empire, but rather to forestall a possible expansion of Serbian power into the territory. The step infuriated the Russians, who, because they were just recovering from their war with Japan and the Revolution of 1905, were unable to respond with vigor, though they vowed that next time they would not stand down if there was a similar Austro-Hungarian provocation in the Balkans. By the summer of 1914, tensions between Austria-Hungary and Serbia were at a fever pitch, with Archduke Franz Ferdinand on his way to Sarajevo to inspect the army divisions that would be used for a potential invasion and occupation of Serbia.

-

In the years before the war, Russia remained something of an enigma in that it combined political backwardness with an economy that was making impressive advances. The nation had begun to industrialize by the 1890s, and, on the eve of the First World War, the potential size of its economy was becoming apparent. In 1914, Russia was the fourth largest industrial power on Earth, having overtaken France. Rather than begin with smaller industrial concerns, Russian industrialization had occurred on a massive scale with gigantic factories sprouting up in the area in and around St. Petersburg, a city that was facing an acute housing shortage and sanitation problems. The booming economy in the years prior to the war also brought about a high rate of inflation and significant social tensions resulting from an exploited workforce, with a significant number of workdays lost to strikes. There was also serious unrest in the countryside, where many peasants continued to try to scrape by on inadequate land holdings and grappled with declining agricultural prices. Politically, the tsarist system of royal absolutism seemed incredibly anachronistic at the start of the 20th century. An unsuccessful war with Japan in 1904 would reveal the numerous failings of the political system and would help bring about the revolution of 1905. The tsarist state survived, but just barely, in part because the army stayed loyal, while the opposition to the tsar was scattered among many different groups. As a concession to those clamoring for change, Nicholas II was forced to accept a parliament, or Duma, but he treated it with disdain and by 1907 had packed it with sympathetic representatives. In order to restore its popularity following the Revolution, the government turned to anti-Semitism and nationalism as unifying forces, but even these proved problematic. As an empire that stretched across two continents populated by numerous peoples with different languages and cultures, Russia had a serious national identity problem.

-

It can be argued that of all the great powers, France was in the best shape domestically on the eve of the war. Even so, the Third French Republic did face some significant domestic conflicts prior to the First World War, including the fact that many Frenchmen still questioned the legitimacy of the republic itself. The Third Republic that was officially created in 1875 was in some ways conceived by accident when it became clear that restoring the monarchy, a move many Frenchmen would have preferred, was fraught with difficulties. In the years that followed, prime ministers came and went but no single party was able to dominate the legislature. Unlike that of the other great European powers, French economic output was fairly stagnant in the decade prior to the war. As a result of this lack of growth, France encountered significant labor unrest with the number of work days lost to strikes increasing every year leading up to 1914.

The fallout from the Dreyfus affair, in which a Jewish officer had been falsely accused of selling military secrets to the Germans, overshadowed life in the Third Republic even after Dreyfus’s pardon in September of 1899. Action Française, a right-wing newspaper, continued to push an anti-Semitic agenda, something that received a favorable response among a significant portion of the French populace, particularly as France’s Jewish population increased with refugees escaping from the horrors of tsarist Russia. Other religious issues were equally contentious, such as the question of the role of the Catholic Church. Although church and state were officially separated in 1905, that decision continued to rankle the more religiously inclined. In the years immediately prior to the war, the Third Republic also debated if they should maintain a three-year military service commitment for French conscripts (to keep up with Germany’s vastly larger population) as well as the controversial question of whether to introduce an income tax to pay for larger military expenditures and a minimal system of old-age pensions.

-

The Italian economy was growing at a nice clip in the years prior to 1914, but the economy still could not keep up with the needs of a rapidly growing population. The industrialized north suffered from a wave of strikes, which, due to the relative weakness of the Italian trade union movement in comparison with its German or British counterparts, provided an opening for extremist groups. One such group was the Syndicalists, a group whose mission was to transform capitalist society through action by the working class, who threatened to use the tool of the general strike to bring down the capitalist system. Meanwhile, in the largely agricultural south of Italy, life had hardly changed since the 18th century; it was still a land of great estates and a hardworking, impoverished peasantry. The desperate poverty of the region would eventually lead to entire villages packing up and emigrating to the United States.

Parliamentary politics in Italy had never been a particularly enlightening sight, and, on the eve of the war, the entire system appeared to be breaking down. When Italy entered the war on the side of the Entente in 1915, the Parliament was not even consulted. As in France, there was a significant anti-clerical element in Italian politics. While the growing Catholic Center Party benefited from the papacy’s continued refusal to recognize the Italian state, it came to realize that it would be useful to have a party that reflected Church desire in order to stop the passage of bills allowing for such things as divorce. As a possible way out of the political quagmire, the government turned its attention to imperial affairs, such as the worthless conquest of Libya in 1911. For more ardent Italian nationalists, this action was not enough, and they clamored for the conquest of Italia irredenta (unredeemed Italy); that is, areas occupied by ethnic Italians living under Austro-Hungarian rule.

-

Great Britain was facing a number of significant issues on the eve of the First World War. On the front burner in the decade prior to the First World War was the question of the extension of suffrage to women. In the first half of the 19th century, Liberals often argued that voting should be limited to men of property, but once the vote was granted to working-class male householders in the reform bills of 1867 and 1884, it opened up the possibility of a further extensions to include women. In the second half of the century a number of women’s suffrage societies emerged that worked for the vote through peaceful means, such as organizing petitions meant to influence Members of Parliament. By 1900, a new, more violent element emerged with the formation of the Women’s Social and Political Union (W.S.P.U.), led by Emmeline Pankhurst. Pankhurst’s group, often referred to as suffragettes, was quite different from the earlier suffrage societies in that the members felt justified in using means such as arson as a tool for bringing attention to the plight of women. When some suffragettes were arrested for violent acts, they staged hunger strikes in prison and brought negative publicity to the government of Liberal Prime Minister Herbert Asquith.

Great Britain struggled over the place of the unelected House of Lords in a nation that was increasingly heading toward democracy. The focal point for this struggle came in 1909 when the Liberals introduced a bill to provide for old-age pensions. In order to finance the plan, David Lloyd-George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, proposed raising income taxes, death duties, and taxing landed wealth. The bill passed the House of Commons, but stalled in the House of Lords, where the Lords broke with tradition for the first time in over two hundred years and rejected a money bill. As punishment for this unprecedented behavior, the Liberal government pushed a bill to limit the House of Lords’ power to a suspending veto lasting two parliamentary sessions. When the House of Lords refused to pass a bill that would effectively strip it of its powers, Prime Minister Asquith threatened to have the king instantly create several hundred new lords in order to stack the upper house of Parliament and pass the bill. With this the House of Lords finally passed the bill.

Yet the most serious crisis facing the British government on the eve of the First World War was the question of Home Rule for Ireland. The Liberal Party had first broached the subject when Prime Minister William Gladstone introduced a Home Rule bill in 1884. The bill failed to win support among the party faithful and, in fact, led to a split within the Liberal Party that helped bring about a long period of Conservative dominance over British politics. By 1914, Asquith was ready to try again to bring about Home Rule. Fearing the domination of Catholics, the Protestants of Ulster began to take up arms to resist home rule, while the Catholic population began to arm in response. Civil war looked almost certain in Ireland, and, to make matters worse, some British army officers indicated that they would refuse to obey if ordered to disarm the Ulster Protestants.