Introduction

As discussed in the previous chapter, there is a bunch of contracts as well as trade practices that have been disapproved by Islamic commercial law. However, there are also contracts which are deemed permissible by Shariah and such contracts have been used in the Muslim societies throughout the centuries. However, the last century saw a revolution in the development of Islamic commercial law and the contracts approved by this law. Thus, we see that the contracts permissible under Islamic law are now adopted and molded in a variety of forms. This is due to the differences between the situation when these contracts were developed through centuries and the drastic changes that have taken place in the sphere of business and finance during the last century or so. Consequently, we find that contemporary Muslim scholars have primarily responded positively to these changes by allowing these traditionally approved contracts to be applied in the modern context within the parameters deemed permissible by Shariah. A significant step in this connection is the combination of different contracts which has enabled Islamic law to come up with the required business and finance structures deemed necessary to cater for the needs of the modern-day needs. These and many other efforts have enabled Islamic financial institutions to present themselves as a practical solution provider to the modern-day demands. Although some critics have raised concern about these developments, it is hardly deniable that contemporary Islamic finance which is founded on the grounds of classical Islamic commercial law has provided a fresh air among the prevailing conventional financial systems.

Combining should not include the case that Shariah explicitly bars. For example, a sale and lending cannot be part of the same set.

The combination cannot be used as a trick to introduce riba by the backdoor, for example, when two parties may practice bay al-’inah even though it is allowed in Malaysia under restriction.

Combining should not be used as an excuse for riba taking. For example, A buys a book from B for $100 today on the promise that B will buy back the book for $120 a year later. The literature quotes such cases from the thirteenth-century practices in the Muslim lands.

Combined contracts should not reveal a disparity or contradiction with regard to their underlying rulings and ultimate goals. Examples of contradictory contracts include granting as asset to someone as a gift and selling or leasing it to the person simultaneously (p. 147).

In this chapter, we present an overview of the famous commercial contracts that are allowed under Islamic law. The classification and division of these contracts have already been explained in the previous chapter. Here, the focus is on the main terms and conditions as well as the practical application of these contracts in human life in general and in the field of contemporary Islamic finance in particular. The contracts discussed in this chapter include murabahah, salam, istisna, ijarah, wakalah, mudharabah, musharakah, bay al-sarf, and rahn as follows.

Murabahah

The root word from which murabahah is derived is ribh which means gain or profit. Thus, murabahah is a sale contract in which the seller earns a profit margin over and above the cost price. For a murabahah sale to take place, it is mandatory that the seller must disclose the cost price so that the buyer is aware of the profit that he is paying above this price. This contract has become the most favorite of the Islamic financial institutions and needs special attention.

Murabahah is also called cost-plus-sale (Al-Zuhayli, 2007) or cost-plus-profit contract (Çizakça, 2011). For a sale to constitute murabahah, some conditions need to be met first. The initial price should be known because it is not possible to add a profit to it if it is unknown. Similarly, the profit margin should also be known because murabahah belongs to the category of trust sales, whereby the buyer consents to pay a specific amount of profit to the seller on the basis of information provided to him by the later. Likewise, the initial price for which the seller bought the item should be fungible so that the cost and profit added to the cost are both known (Al-Zuhayli, 2007).

It is noteworthy that the initial price of a murabahah sale also includes extra costs incurred by the seller. For instance, if the seller bought an item for 100 but then paid 20 more for its delivery, the price will be counted as 120. Therefore, selling this item for 150 will mean that the profit margin is 30.

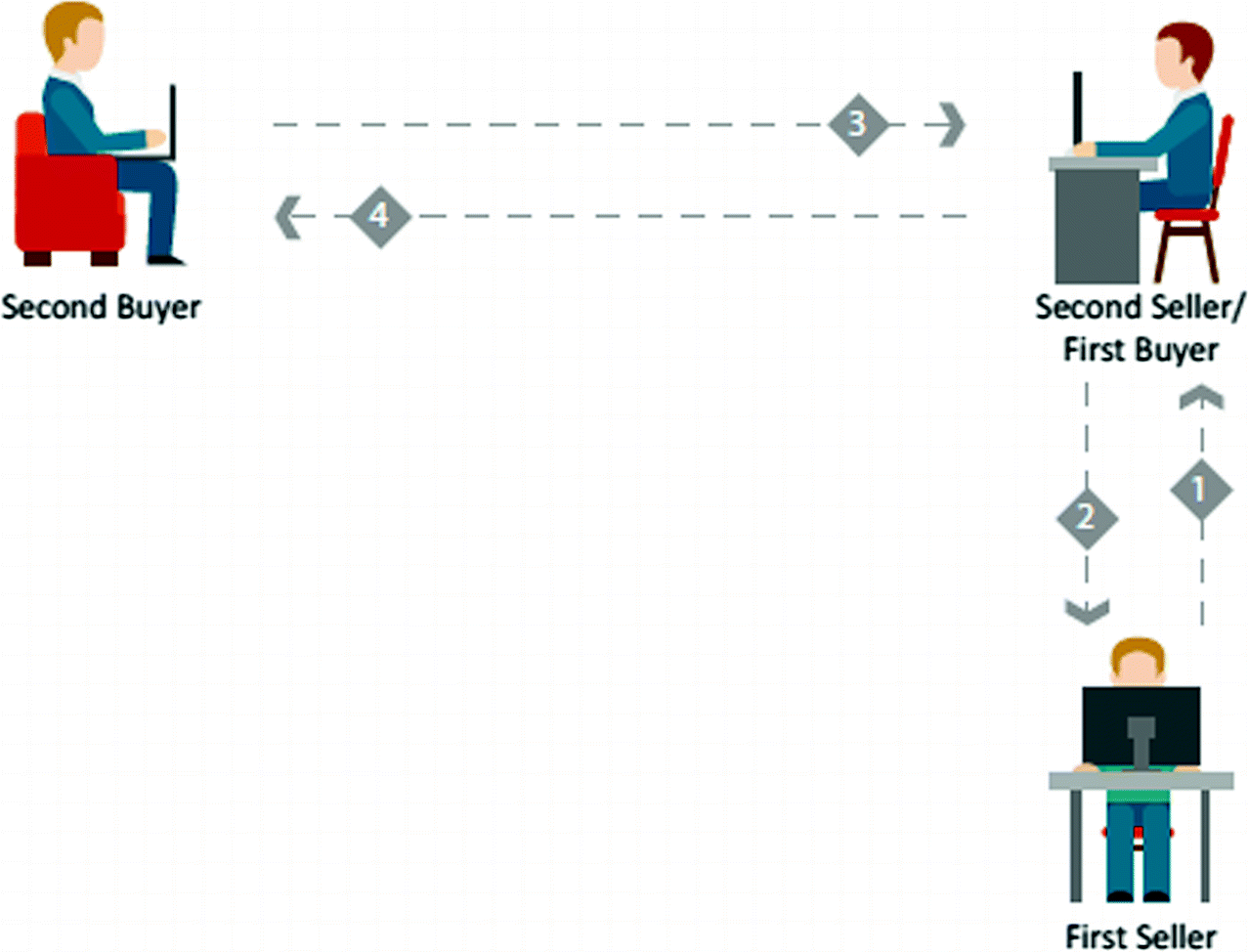

Ordinary murābaḥah structure

- 1.

The first buyer (who is also the second seller) purchases an item from the first seller. This sale is on either cash basis or deferred basis.

- 2.

The first buyer pays the price of the purchased item to the first seller, either on deferred basis or on cash basis as the case may be. However, if he is to pay on deferred basis, he must inform the second buyer that his purchase of the item from the first seller was on deferred basis.

- 3.

The first buyer/second seller then sells the item to the second buyer. He also discloses the cost price to the second buyer, further explaining whether the first sale was on cash or deferred basis.

The second buyer pays the price to the second seller either on deferred basis or on cash basis (ISRA, 2016, p. 213).

In its classical dimension, murabahah contract was envisaged to be used in a particular situation. If a consumer is not shrewd, he may be charged a huge profit margin by a skilled seller. Therefore, the disclosure of original cost price by the seller will satisfy the buyer with respect to the profit earned charged to him. However, due to the close proximity of a murabahah sale with the conventional debt-based loan mechanism, a murabahah contract can be used to create a deferred debt with the desired profit margin. This is what has led to the increased popularity of this mode of financing in the Islamic finance industry.

It is pertinent to mention that murabahah in its classical form need not be a credit sale as it can also be a spot transaction. However, it is due to the nature of banks and other financial institutions that currently murabahah has become an equivalent to credit sale. In its simple form, an Islamic bank would buy a commodity from vendor on cash price and would sell the same to its customer after adding its profit margin to it. Thus, the customer receives the commodity it is looking for, while the Islamic bank gets paid in installments like a simple financing contract in a conventional bank.

Traditionally, it was envisioned by the forefathers of Islamic banks that equity-based contract including musharakah and mudharabah will be the foundation of Shariah compliant banking. However, murabahah was approved initially to kick-start the system with the aim to shift gradually toward risk-sharing and equity-based contract. But things did not go as expected. Even when Islamic banking is approaching its golden jubilee in less than a decade, murabahah has become the norm with a meager share of equity-based contracts. This demands an inquiry into this state of affairs.

Due to the fact that most Islamic bankers have an academic and practical background in conventional banking and finance, they find murabahah to be most aligned and fit structure to the conventional banking system. The risk level in a murabahah transaction is akin to a debt contract in conventional banks which makes this contract an eye apple for Islamic banks. The regulatory risk treatment endorses this idea. Additionally, this mode of financing is also free from the moral hazard issue associated with equity-based contracts. Furthermore, the risk-averse nature of banking industry is also adding to this trend. Risk-sharing is said to be a feature of the capital markets while banks are deemed as providing safety and security of the depositors’ funds by undertaking as little risk as possible.

Likewise, equity-based contract also suffers from the issue of agency problem. In fact, equity-based Islamic banking was tested at few places but the experiment did not succeed because in both musharakah and mudharabah has no say while the customer can claim losses in the venture. This leaves an Islamic bank with no resort but to bear the losses, a situation that is skilfully handled under a murabahah contract because after the sale of the commodity to the customer, the Islamic banks can retain the ownership of the sold commodity as pledge until all the outstanding balance is paid by the customer. These are some of the factors that make murabahah the most favorite contract of Islamic banks today.

Thus, murabahah today is the most favorite contract of Islamic banks on both their liability and asset side, especially the later side. Customer can deposit money with these banks and can also get financing through murabahah. A simple example should suffice to explain the point. A customer needs to buy a car. She approached an Islamic bank and makes a request for this purpose. After the procedure is followed, the Islamic bank buys a car from a dealer on spot basis and then sells it to the customer, after adding its profit margin to it, on deferred basis. The customer pays the price in installments.

Salam

In simple words, salam can be described as forward sale in which one party pays the price for an item in advance while its delivery is deferred to a specific date in the future. If a person needs some fungible item in the future, he may pay for it today in order to get a discount for early payment. Similarly, a person who will get something in ownership in the future may need cash today. This is especially true in some cases like farming, whereby the farmers need cash to buy the things (seed, fertilizer, etc.) needed for farming. Thus, salam fulfills the needs of both the parties.

Recalling our discussion in the previous about the prohibited elements in Islamic commercial law, one should logically expect salam contract to be banned by Shariah. This is because the item of sale is currently not in the possession and ownership of the seller. In fact, the item of sale may not even exist at the time of sale and this is a form of uncertainty or gharar which is prohibited by Shariah. However, this contract has been explicitly declared legal by the Prophet (SAW) and the Muslim scholars are unanimous on its permissibility. The ambiguity or uncertainty is removed by a detailed description of the item of sale. The logic for the permissibility of salam contract is said to be the need of the masses for such mechanism.

Just like other permissible sale contracts in Islamic commercial law, salam should also fulfill all the requirements of a legal sale under Islamic law. However, there are extra conditions for salam contract too. These conditions pertain to both the price and object of salam. The most important condition for the validity of salam contract pertaining to its price is that the price should be paid in advance. This is understandable because the object of salam is already deferred, and if even the price is deferred, it would lead to the sale of two liabilities which is not permissible under Shariah rules. However, since the price in salam is paid in advance, it is the object of salam that needs to fulfill extra important conditions including the following.

The genus of the item, i.e., whether it is wheat or barley, should be known. Also, its type should also be known. Additionally, its characteristics should also clearly be specified, just as its amount should be made known via volume, number, weight, or size. Next, the price and the item should not be such that belongs to the category of ribawi items. These are six items including gold, silver, wheat, dates, salt, and barley. Thus, condition is put because the ruling for the exchange of such items is that it should be hand in hand. Additionally, the item should be such that it can be identified by specification. Likewise, the item should be such that it should exist and be easily available in the market at the time of delivery. It is pertinent to note that option is not available in a salam contract and it is binding on the parties if the salam object is delivered by the seller as per the specification. The place where the item is to be delivered should also be known (Al-Zuhayli, 2007). Thus, it is evident that these detailed conditions remove the gharar in salam contract and make it permissible in the eyes of Shariah.

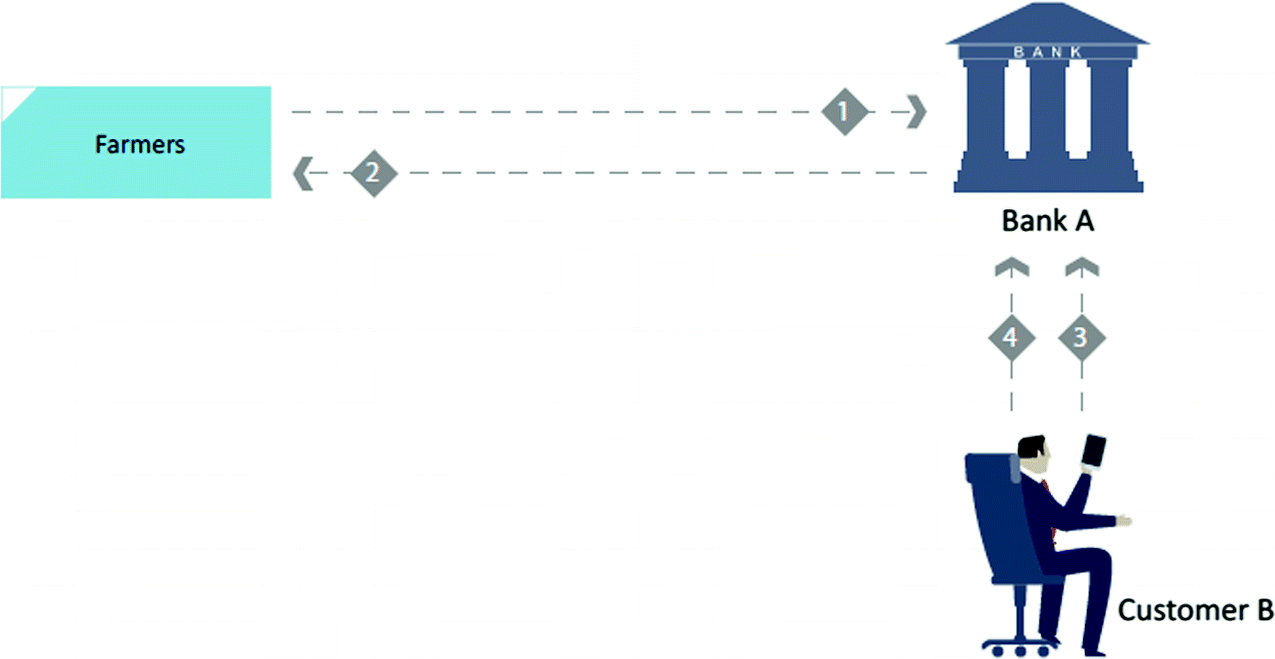

Application of the salam contract in agricultural financing

- 1.

A farmer enters into a salam contract with an Islamic bank to sell a specified amount of wheat to be delivered on a specific future date for a fixed price.

- 2.

The price of wheat is paid by the Islamic bank to the farmer on spot basis.

- 3.

The bank also enters into a promise with another customer B, whereby the customer undertakes to purchase the wheat from bank that is to be delivered to it on the future date.

- 4.

Once the farmer supplied the wheat to Islamic bank on the specific date, the bank informs customer B to execute sale contract and take delivery of the wheat (ISRA, 2016, p. 225).

Due to the diverse nature of the demands of customers, Islamic banks have found salam contract very useful for some products and situations. For instance, these banks may want to finance farmers for which salam is the most suitable contract, whereby the Islamic banks provide financing to farmers and buy their produce from them in advance. However, since Islamic banks do not really need the produce which will be delivered to them in the future, they need to dispose these as well. This is where salam proves very helpful. On the one hand, Islamic banks enter into a salam contract with farmers and buy their produce in advance. On the other hand, they enter into a second or parallel salam contract with potential buyers of such produce. The banks keep the marginal difference between the two salam contracts as their profit.

Istisna

Istisna is the contract of manufacturing which shares many features with salam contract just as the two are unique in certain ways. In fact, some jurists consider the two as the same. However, there are some differences between the two as we shall explain soon. Like salam, istisna is a sale contract in which something that does not exist is the subject matter of the contract. For instance, a customer orders a carpenter to make a bed of specific features for the orderer; this is where istisna is different from salam because salam does not involve manufacturing. Hence, the contract is concluded on something that does not even exist at the time of concluding the contract. Once the object is manufactured, the two parties need to renew the offer and acceptance and the sale takes place eventually.

The need for istisna contract is clear. There are certain professionals in every society that have the skill to manufacture different types of items required by masses in a society. Such objects do not exist initially and it is the effort, skill, and time of these professionals that bring these items into existence. To do so, these skilled persons may need to be instructed in advance just as they may need to be financed in order to arrange the raw material for this purpose. This is where istisna plays its role in fulfilling the needs of both the manufacturers and those who want items manufactured by them.

The item to be delivered must be clearly specified in terms of its nature, quality, and measurements.

The manufacturer (builder) must make a commitment to produce the item as per the description and specifications.

The manufacturer (builder) is to deliver the item upon the completion of its production without needing a fix completion date.

The contract cannot be revoked once the production process has started except where items are found to be not meeting the specifications as per the agreement.

The payment can be made in installments linked with the progress of the work or in a lump sum before or after the time of delivery.

The manufacturer (builder) alone is responsible for obtaining the inputs needed for the completion of the production process.

The manufacturer (builder) cannot assume the role of a financial intermediary between the buyer and the third party, especially if the buyer has become unable to meet the obligations toward such a third party.

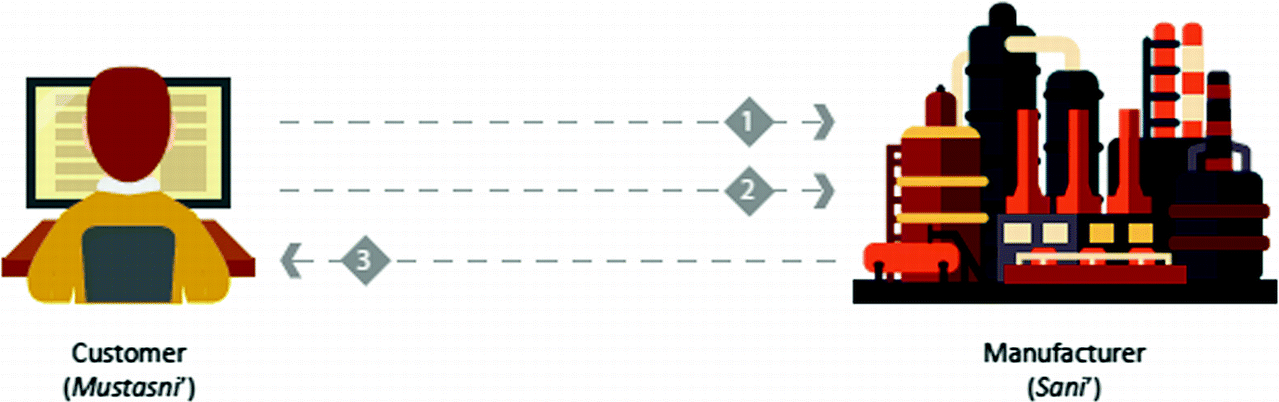

Classical istisna structure

- 1.

A customer approaches a manufacturer and requests him to manufacture a specific item for him which is to be delivered on a specific date, at a price agreed by both which is to be paid at an agreed date in the future or on spot.

- 2.

The customer accordingly pays the price to the manufacturer either on cash or on deferred/installment basis.

- 3.

Once the asset is completed, it is delivered by the manufacturer to the customer on the stipulated date (ISRA, 2016, p. 219).

Istisna is practiced in Islamic banks currently. This contract is especially suitable for the making of buildings and other projects such as bridges, highways, ships, and the like. In fact, this contract suits the purpose of infrastructure and project financing. Therefore, if a customer needs a house, for example, it can be built by the Islamic bank under the contract of istisna. However, just like salam contract, the Islamic bank will need to find a party which can construct the object on its behalf for the customer because the banks do not perform such duties. Therefore, a parallel istisna is signed by the Islamic bank with another party, whereby the Islamic bank asks that party to construct the house as per the requirement and description provided by the client. After the completion of the construction, the Islamic bank takes the house into its ownership followed by its sale/delivery to the client.

Ijarah

Like all other types of sale contract, the contract of ijarah or lease has been discussed in detail in Islamic commercial law. It follows all the general conditions and requirements of a sale contract, just as it has its own specific conditions and requirements that need to be observed. The essence of this contract is the sale of usufruct against compensation or rent. Like salam and istisna contracts, ijarah is the sale of something, i.e., the usufruct, which does not exist at the time of sale but exists in the course of time. According to the majority of the jurists, the subject matter of lease contract can also be the usufruct of an item that is to be made in the future.

The need and rational of a lease contract are evident. One has different types of needs including the need to use the usufruct of an item without having the need to own that item itself. Thus, on the one hand, there are the owners of such items who do not need or want to use such usufruct generating items themselves and on the other hand there are those who need the usufructs of such items only. A lease contract brings these two groups of people together. Those who need to use usufruct get them by paying rent or compensation to the owners of such items. Examples include the lease of a car, a house, an office, an aeroplane, a piece of machinery, and the like.

Lease of a moveable asset

- 1.

The lessor leases a house/car, etc., to the lessee for a specific rental amount.

- 2.

The lessee pays the rental as per the terms of the agreement, and at the end of the lease period, the lessee returns the leased asset back to the lessor (Saleem, 2013, p. 57).

Apart from the general sale conditions, there are specific conditions required for a lease contract to be legally valid under Islamic law. Some of the important conditions include the following.

- 1.

Knowledge of the type of benefit or usufruct to be derived from the object,

- 2.

Knowledge of the period of the lease, and

- 3.

Knowledge of the nature of labor in leasing the labor of skilled or unskilled workers (Al-Zuhayli, 2007, p. 391).

Due to the nature of ijarah contract, it is important that the object of lease should be such that they can be hired or utilized but their substance of corpus remains unconsumed. Therefore, currency, fuel, cotton, edible, ammunition, and candles cannot be leased because they perish after utilization. Likewise, it is also not permissible to lease one item in compensation for another item of similar genus like house for house.

The contracted usufruct has to be ascertained to avoid any dispute.

The lease period must be specified. However, in the case of a wage/service, any of the two, i.e., the amount of work or the time period for a job should be known.

Benefiting from the hired goods should be possible. As such, lease of a nonexistent asset for usufruct of which a description cannot be determined precisely is not allowed, because such gharar about the description and the time may lead to disputes. In other words, the purpose of the contract must be capable of being fulfilled and performed.

The handing over/delivery of the contracted goods for taking their benefit is essential. No rent becomes due merely because of execution of the contract, unless the subject of the lease is delivered and made available to the lessee. However, advance rent can be taken when availability is ensured for the period of the lease.

In the case of workmen or service, the contracting person should be capable of undertaking the job. Therefore, hiring a runaway animal for riding or usurped assets is invalid.

The usufruct of contracted goods must be lawful, meaning that the purpose of ijarah should not be unlawful or haram.

The usufruct should be conventional or according to the tradition of the people (Ayub, 2009, pp. 281–282).

With respect to liability in connection with the leased asset, the liabilities arising out of the ownership will be borne by the lessor or owner of the object. For example, in the case of leasing a house or a care, the owner will be responsible for paying taxes related to the house/car. However, liabilities like paying of electricity/water bills and fuel charges will be borne by the lessee. Similarly, the lessee is not responsible for damages caused to the leased asset unless it is proved that it was caused by the lessee’s negligence, misconduct, or breach of terms.

- 1.

By means of a promise to sell for a token or other consideration, or by accelerating the payment of the remaining amount of rental, or by paying the market value of the leased property.

- 2.

A promise to give it as a hibah or gift (for no consideration).

- 3.

A promise to give it as a gift, contingent upon the payment of the remaining installments.

Furthermore, the rental amount in finance lease is higher as compared to operating lease. This is because the rental amount in finance lease is almost equal to the amount paid under installment sale; both installment sale and finance lease have more or less the same economic outcome.

In the sphere of Islamic capital market, ijarah sukuk, the Shariah compliant alternative to conventional bonds, is a very famous instrument. Under normal ijarah sukuk structure, a special purpose vehicle (SPV) established by the entity that needs to raise funds is formed which issues sukuk to the investors and raises funds from them. Next, the SPV purchases an asset from a supplier and leases it to the entity. The entity uses the asset and makes rental payment which is distributed among the sukuk investors periodically. At the end of the contract, the entity purchases the asset from the SPV pursuant to a purchase undertaking given by the entity. The sukuk investors are paid back their initial investment.

Wakalah

The word wakalah has several meanings including delegation, authorization, or performing a task on behalf of another. In its standard no. 23, AAOIFI defined wakalah as the act of one party delegating the other to act on its behalf in what can be a subject matter of delegation. Thus, wakalah is a contract in which the principal (called muwakkil) authorizes a party as his agent (called wakil) to perform tasks on his behalf (ISRA, 2016).

Wakalah is a non-binding contract by nature, and therefore, any of the two parties can withdraw from it by mutual agreement, unilateral termination, or discharge of the obligation. Additionally, wakalah can be paid or voluntary. Hence, the principal will be required to pay the agent if they agreed it to be so. Similarly, wakalah can be general or restricted. In general wakalah, the principal asks the agent to perform a specific task, e.g., buy a house, without specifying any further detail. But in restricted wakalah, he restricts the buying of house with, for instance, a particular price. Similarly, wakalah can be restricted to a certain period of time. But it can also be left unrestricted with respect to time if the two parties agreed (ISRA, 2016). It is the responsibility of the agent to perform all delegated tasks as per the instructions of the principal and exercise due care and diligence in the process. Any action performed by the agent on behalf of the principal with due diligence will be deemed an action by the principal (Ayub, 2009).

A particular type of agency has been recognized under Islamic law known as fadhuli or unauthorized agent. It is a person who involves in the matters of others without concern. It is a type of contract in which one person acts on behalf of another without prior authorization. According to the most preferred opinion, this contract is valid but pending the approval of the principal (Saleem, 2013). If approved, it will have a retrospective effect and all right and liabilities of an agency contract will come into effect from the time of concluding the unauthorized act.

The principal should know the agent, either by name or by his physical appearance. Likewise, the agent should identify his principal either by name or by his characteristics.

The rights and responsibilities of the transaction entered into by the agent shall lie with the agent, such as taking possession and delivery of the purchased asset.

However, if the agent attributes the transaction to the principal, the rights and responsibilities of the transaction shall lie with the principal.

The agent as trustee shall not be liable in the event of loss or damage of the asset except if such loss or damage is caused by his misconduct, negligence, or breach of specified terms.

If the agent is given remuneration for the provided service, the Shariah ruling of ijarah shall apply (ISRA, 2016, p. 262).

Wakalah is frequently used in different Islamic finance contracts. In fact, there is hardly an instrument where wakalah is missing. Even in a simple murabahah transaction, the client is appointed as wakil by the Islamic bank to purchase the asset on the bank’s behalf. But wakalah has gained specific importance as Islamic finance is advancing further. The concept of wakalah bi al-istithmar or investment agency is becoming increasingly popular, especially in the sphere of sukuk. Under this mechanism, as elaborated by Ayub (2009), the Islamic financial institutions manage funds of the investors on the basis of agency. They manage these funds on agency basis and charge a pre-agreed fee for their services irrespective of the profit or loss of the respective portfolio. The fee can be charged in different possible ways: It can be a part of the percentage of investment amount on monthly or annual remuneration basis, or it can be fixed in a lump sum. However, it is necessary to determine one of these mechanisms before the launch of the fund.

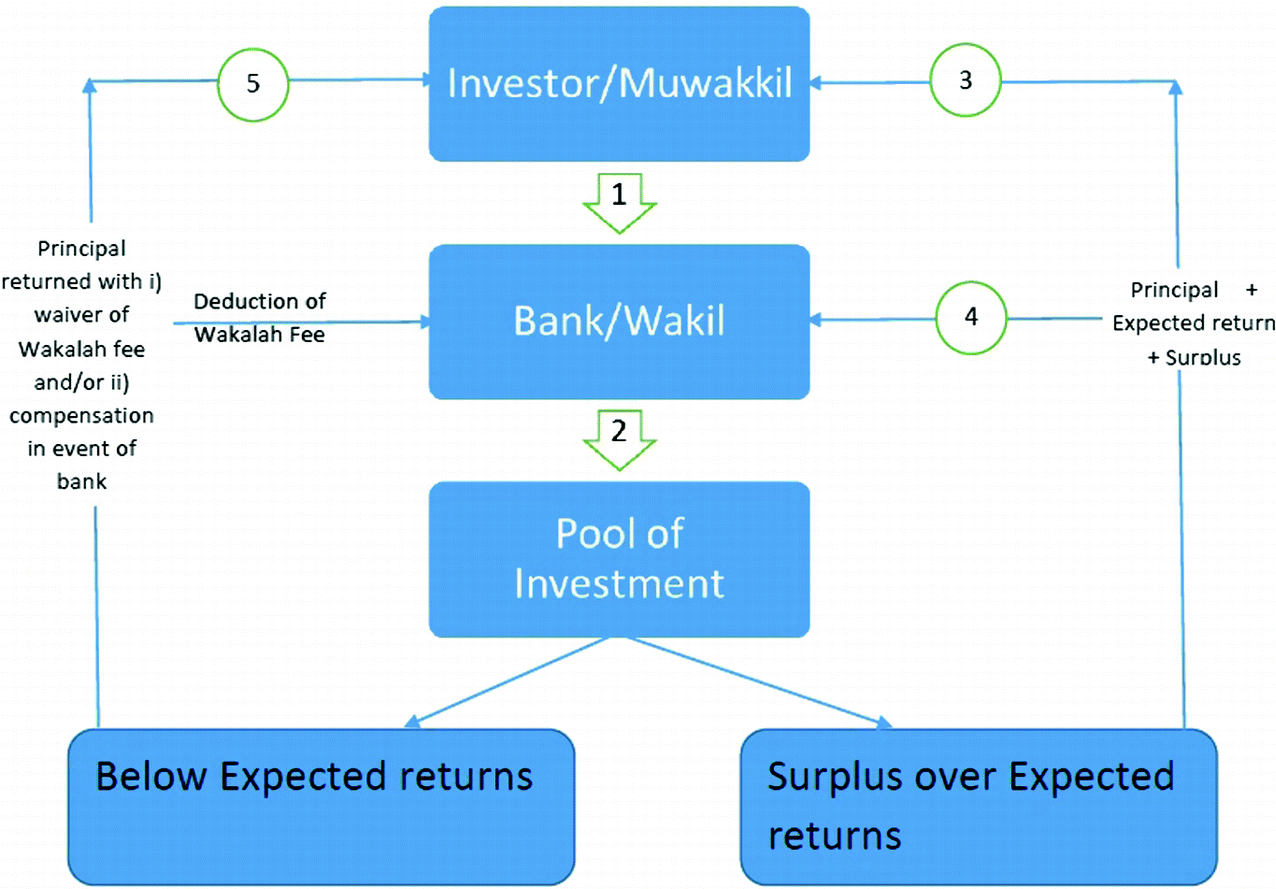

Basic structure of a fee-based wakalah bi al-istithmar contract

- 1.

According to the agency agreement, the investor appoints the Islamic bank as its investment agent.

- 2.

The bank invests the money as per the terms of the agency agreement.

- 3.

The investor receives the expected returns as well as the principal amount at the end of the contract.

- 4.

If there are any surplus returns, they are either shared by the investors and Islamic bank, or given to the bank as incentive fee.

- 5.

In the event of bank’s negligence, the principal is returned to the investor along with waiver of wakalah fee and/or compensation (ISRA, 2016, pp. 274–275).

In the Islamic capital market, wakalah sukuk are becoming increasingly popular. Under a plain wakalah bil istithmar sukuk, the principals (sukuk investors) appoint an agent to invest the former’s capital in order to generate profits. The agent charges a fee for its services. The risk of the acquisition and investment is borne by the principals. Similarly, they are entitled to any profits generated from the investment activities.

Musharakah

Social dynamics, cultural patterns, and demographic explosion over the centuries eroded the personal intimacy and trust on which participatory finance flourished unabated till the close of the thirteenth century in the Muslim world.

There was a lack of adequate legal safeguards to the capital providers against loss, including discrimination in allowing interest payments as a cost deduction in conventional lending but not of the profit share in Islamic finance.

At both ends of the scale—demand or supply—mudharabah finance is neither pure equity nor pure debt. It is a mixture which takes in part the features of them both. It would, for example, be misleading for the firm to treat the funds as equity and for the bank to treat them as debt. This impurity gives rise to agency confusion, which arguably can be more serious in mudarabah financing than in either equity or debt financing, making mudharabah the least attractive proposition to both the bank and the firm (p. 120).

In spite of the fact that musharakah and mudharabah are not attractive to Islamic financial institutions, it is not deniable that the industry players continuously long for a widespread use of these modes. These are thought to be the way forward if Islamic finance ever wants to achieve its dreams of social justice and equity.

The word musharakah from the root word sharikah linguistically refers to mixing of two properties in such a way that defining the separate parts is no more possible; it also means sharing and participation. Technically, it is defined by jurists as a contract between a group of individuals who share the capital and profits. The wisdom in permitting partnership is that it allows the partners mix their properties in such a way that leads to generating maximum benefit than could be generated individually (Al-Zuhayli, 2007).

There are two broad types of partnerships discussed in Islamic commercial law: general partnership and contractual partnership. In general partnership, there is very little flexibility for the partners as compared to the second category (Al-Zuhayli, 2007). In general partnership, two or more persons become joint owner of a property without entering into a formal partnership contract. There are two ways in which such partnership could be established: by operation of law or via a contract (other than partnership contract). Example of the first type includes inheritance while bequeath and gift are examples of the second type (Saleem, 2013). General partnership is further divided into voluntary and involuntary. Voluntary general partnership is established as a result of joint purchase or joint receivership of gifts or bequests accepted by partners, whereas involuntary general partnerships are formed without an act of approval by the partners like the automatic inheritance of property by the heirs (Al-Zuhayli, 2007). Contractual partnership, on the other hand, is defined as a contract between two or more partners, whereby they agree to partner in the capital and profit. Since the parties concerned willingly enter into a contractual arrangement for joint investment and sharing of subsequent profits and losses, it is considered as the proper type of partnership (Saleem, 2013) and it can also be termed as “joint commercial enterprise” (ISRA, 2016). This is the type that concerns us in this section.

- 1.

Partnership in capital: In this type of partnership, all the partners contribute capital into the business venture. This type of partnership is further divided into two types: general and equal. Under equal partnership, the contributed capital, debt liability, and mutual responsibility are equally shared by each partner. In general partnership, on the other hand, such equality is not required and this type is most akin to the modern concept of business partnership.

- 2.

Partnership in services/labor: This is a partnership agreement between two or more parties to provide a service jointly and share the profit from the work as per the agreed-upon ratio. There is no capital contribution required in monetary form for this type of partnership.

- 3.

Partnership in goodwill: Under this type of partnership, the partners enter into partnership on the basis of their goodwill and creditworthiness. They buy assets on credit on the basis of their creditworthiness for the purpose of making profit. The percentage of profit and liability sharing is determined by the partners mutually.

- 4.

Partnership in profit: This type is famously known by mudharabah which stands for capital contribution from one partner and labor from the other. The profit earned is shared between the two as per agreed ratio while losses are borne by the capital provider. This type will be discussed in detail later.

The ratio of profit sharing among the partners should be fixed at the time of concluding the contract. However, this ratio cannot be a fixed amount; rather, it has to be a specific percentage of the expected profit earned. This is important in order to avoid disputes and gharar as no profits may be realized from the venture.

It is permissible to have profit-sharing ratio which is not proportionate to the capital contributed by the partners. However, a sleeping partner, i.e., a partner that is not taking part in the business management, cannot have a share of profit more than his capital contribution.

Losses can only be shared as per the capital contribution.

Although the capital of partnership should be in monetary form, the jurists allow to contribute tangible assets as the capital of partnership provided that all partners agree to it and that the monetary value of these assets is determined.

Not all the partners are required to participate in the management of the business.

It has been discussed previously why musharakah is not very famous among Islamic banks. However, this contract is still used to a certain degree. Of particular importance is a unique type of partnership called musharakah mutanaqisah or diminishing musharakah. In diminishing musharakah, the Islamic bank enters into partnership contract with a potential buyer to buy an item. Thus, the two become owners of the said item. Afterward, the Islamic bank leases its portion of the bought item to the customer and the customer pays monthly rental for this. However, the customer simultaneously buys a small portion of the bank’s share in the item on frequent basis which leads to a decrease in the ownership of the bank in the said item. With the passage of time, the share of the bank decreases, a situation denoted by the term “diminishing,” until it is wholly bought by the customer who becomes the ultimate owner of the item.

Musharakah mutanaqisah structure for home financing

- 1.

A house which is already completed is bought by a customer who also pays a deposit of 10% of the price.

- 2.

Next, the customer enters into a musharakah mutanaqisah contract with the Islamic bank.

- 3.

The Islamic bank pays the remaining 90% of the price to the house developer. The bank, thus, becomes the owner of the 90% shares of the house.

- 4.

The Islamic bank then leases its 90% share in the house to the customer who pays rental to the bank on monthly basis.

- 5.

Each month, the customer pays the monthly rental but also buys a small share of the property from the Islamic bank until he becomes the owner of the 100% shares of the house at the end of the contract tenure (ISRA, 2016, p. 263).

Like Islamic banking, musharakah sukuk is also not among the favorite instruments in Islamic capital market. However, musharakah sukuk are found in the market. A musharakah sukuk represents undivided ownership of the sukuk holders in the business venture. Normally, this sukuk is issued to undertake a specific project or to have a stake in the business of the issuer. Accordingly, the funds raised from sukuk investors are injected into the issuer’s business or project. The return from the venture is then distributed between them as per the agreement. At the end of the term, the issuer purchases the portion of the sukuk investors in the venture and they get their money in full.

Mudharabah

As defined in the previous discussion on musharakah, mudharabah is a type of partnership in which capital is contributed by one party while the skill and labor are added from another party. Based on this structure, mudharabah is also called silent partnership. The main difference between a mudharabah and musharakah is that in musharakah, all the partners can partake in the management of the venture. Similarly, another distinguishing feature is the bearing of losses; in mudharabah, all the losses are to be borne by the capital provider while the entrepreneur only loses his effort and time. It is also a requirement for mudharabah that the capital contributor (known as rabb al-maal) should refrain from interfering into the venture management by the entrepreneur. Mudharabah is also called qiradh and muqaradhah by some jurists.

Mudharabah process flow

- 1.

Rabb al-mall (also known as sahib al-maal) contributes the capital to the business project.

- 2.

The mudharib contributes his efforts to the business project.

- 3.

As a result of business activities undertaken by the mudharib, profits are generated.

- 4.

Mudharib receives his share from the profit generated.

- 5.

The sahib al-mall similarly receives his portion of profit.

- 6.

However, it may be the case that losses are incurred in the process.

- 7.

In the case of losses, they are offset by the profit from the business.

- 8.

However, in case the losses are more than profit, they are borne by the sahib al-mal while the mudharib loses in the form of his efforts gone unrewarded (Saleem, 2013, p. 112).

The practice of mudharabah was prevalent even in the pre-Islamic Arabia. Even the Prophet Muhammad (SAW) worked as mudharib at a young age. It is also argued by many that this structure was later on exported to some parts of Europe. In any case, mudharabah is a perfect structure where a person is skilled but does not have the required capital to utilize his skills in doing business. Similarly, it fits the needs of a capitalist with no business skills or no time to do business. The two parties can reap the benefits of their respective strengths by partnering under the contract of mudharabah.

Mudharabah is of two types: restricted and unrestricted. In restricted mudharabah, the capital provider puts some restrictions on the entrepreneur regarding the management and use of funds. For instance, he may be restricted about the types and/or period of investment, location of investment, as well as the use of funds or any restrictions that the capital provider deems appropriate. On the other hand, there are no such restrictions in unrestricted mudharabah and the entrepreneur enjoys freedom in all these aspects.

The capital of mudharabah should be in cash or liquid form. It should not be in kind in the form of commodities and goods because of the fluctuation in their prices.

The amount of capital should be known.

Similarly, the capital should be present. Therefore, a debt cannot be made the capital of mudharabah.

The capital should be delivered to the mudharib to enable him to do business with it which is the purpose of such venture.

The capital provider has the right to appoint more than one entrepreneur in which case they both will utilize the capital jointly.

One entrepreneur can also be hired/appointed by many capital providers.

The losses will be borne by the capital provider and the entrepreneur will not be liable for these except in the case of misconduct, negligence, and breach of terms.

A mudharib should exercise due diligence and care in the management of the business venture.

The liability of the capital provider is restricted to the capital he has contributed. Therefore, an entrepreneur should not incur liabilities greater than the capital except with the explicit permission of capital provider to do so.

In contemporary Islamic finance, mudharabah is normally used on the liability side of the Islamic banks. A customer wanting to deposit with these banks opens account on mudharabah basis. This mudharabah is usually unrestricted because the Islamic bank has the freedom to invest it as mudharib as per its discretion. Any profit earned from the investment is shared as per the agreed ratio while losses are borne by the account holder. The Islamic banks acting as entrepreneurs invest the funds further on mudharabah basis or on the basis of other Shariah compatible modes of financing. In the first case, the mechanism is called two-tier mudharabah; there are two mudharabah transactions in this scenario: the first one between the fund depositor and the Islamic bank (where the Islamic bank acts as entrepreneur) and the second one between the Islamic bank and the financier (where the Islamic bank acts as capital provider). While the use of two-tier mudharabah in Islamic banking seems appreciable at surface, it has been criticized by many due to the fact that Islamic banks keep themselves on the safe ground by transferring the losses to the original capital provider (depositor of fund) while they share the profits with him.

Apart from Islamic banking, mudharabah is also utilized in Islamic capital market in the form of mudharabah sukuk, though it is less frequently used. Under a mudharabah sukuk, the investors (sukuk holders) enter into a mudharabah agreement (via purchasing of mudharabah sukuk) with the issuer (mudharib) to invest in a Shariah compliant business. The issuer uses the funds raised for the specific venture and the income generated from the venture is distributed periodically among the two as per the agreement. At the end of the venture tenure, the issuer purchases back the sukuk via a purchase undertaking and the sukuk are deemed, thereby enabling the sukuk investors to get back their initial investment.

Bay Al-Sarf

Bay al-sarf means exchange of money for money. This includes the exchange of currency, the exchange of gold for gold or silver for silver or gold for silver. This type of sale is permissible in Shariah and it has its own particular conditions that should be met in order for such sale to be valid. The legality and conditions of such sale are derived from a famous Hadith of the Prophet Muhammad (SAW) in which he ordered that gold, silver, wheat, barley, dates, and salt should be exchanged equal and on spot. This Hadith is known as the Hadith of six commodities and the Muslim jurists extended this ruling to other items apart from these six items, like the currency in current times.

The jurists derived certain conditions from this Hadith which should be observed in bay al-sarf. The first condition is that the counter values should be taken in possession before the parties leave each other. Second, the exchange should be equal in terms of weight and/or value. Likewise, it should be on the spot and cannot be deferred to future. These rules also apply to currency exchange. However, the same Hadith allows non-equality in the case when two different items are exchanged, but on the spot exchange is still required. For instance, the exchange or sale of the currency of one country (e.g., US$ versus US$) must be equal and on spot. However, an exchange between two different currencies is allowed to be unequal but it must be on spot still. Deferment is not allowed in either case.

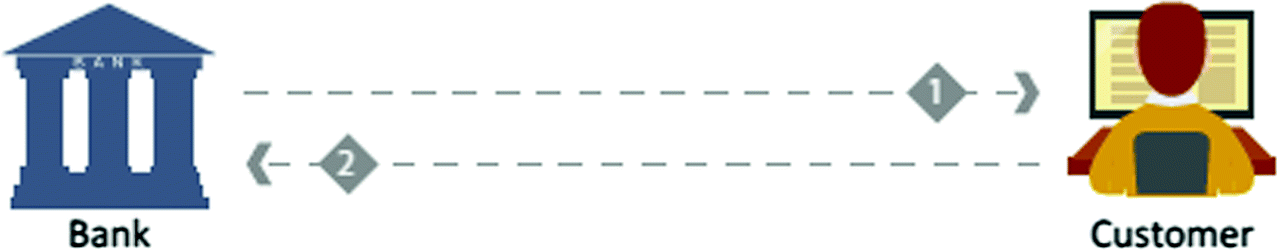

Structure of bay al-sarf in spot forex

- 1.

Bank sells a specific currency to the customer and delivers it to him on spot.

The customer pays the price of currency in a different currency on cash basis (ISRA 2016).