6

Violence and Venality 1947 to the Present

On a warm, muggy day in September 1947—scarcely a month into the freedom India had longed for—Delhi exploded in blind fury. Fed by murderous hate and a desire for vengeance, violence, stoked by the plight of West Punjab’s refugees, covered the entire range of human bestiality—pillage, arson, murder and rape.

Violence was not new to Delhi. The city had experienced everything in its long and chequered existence. In 1398 it was so comprehensively sacked by Tamerlane that, as one literary source has it, “for two months afterwards not a bird moved a wing in the city.” On 11 March 1739 the Persian invader Nadir Shah put Delhi to the sword, and a hundred thousand persons were slaughtered in a single day. In the nineteenth century the British too proved that putting innocent people to death is the privilege of those in power. Their atrocities could be chillingly cold-blooded, as was shown by the reprisals visited on Delhi after the 1857 Mutiny, during which Captain W.S.R. Hodson took out his pistol and shot to death two sons and a grandson of Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah—after they had surrendered from their place of refuge—because, as he put it, “I confess I did rejoice at the opportunity of ridding the earth of these wretches.”

What Delhi witnessed in September 1947—and would again a few decades later—was, therefore, nothing new. Except in one respect. While in the past the perpetrators had been either invaders or interlopers, this time they were neighbours or friends who had lived together as fellow citizens despite distinctions of religion, region, creed and custom. Until one day one group had turned on the other in truly demonic rage. While the killers were purportedly avenging kins-men killed in Pakistan, the victims chosen for retribution were innocent of the crimes across the border. Paradoxically, the killers and the killed on each side were victims of the communal madness their “leaders” had preached and which would haunt India long after alien rulers had been replaced by a homegrown species of purblind politicians.

The year 1947 was no annus mirabilis for a free India, but a year anointed by crimes, without logic or justification, by religious hate which would intensify with each decade. Needing no particular denomination to vent itself on, this hate would go beyond Hindu-Muslim hostility because there were others in India’s complex religious mosaic—Sikhs, Christians and Buddhists—against whom it could be directed. Any number of permutations and combinations were possible, if the will to divide people for political gains existed, which it did in abundance, as the years after Independence would show. And which the Sikhs would experience first-hand.

Before communal madness again overtook the country, India provided convincing proof of the versatility and drive of her gifted people. There were large-scale industrialization and agricultural breakthroughs. Since famines had dogged India during the years prior to Independence, self-sufficiency in food was given high priority in the First Five-Year Plan (1951–6). Next, those in favour of rapid industrialization got the upper hand and agriculture took a backseat for over twelve years, until it was again given top priority towards the end of the 1960s. In the industrial sector, India had always been a market for British manufactures, but in the changed order after Independence the groundwork for a vast variety of industrial products was laid within the country. These ranged from steel, locomotives, heavy machinery, ships, aircraft and automobiles to the setting-up of power-generating projects, oil refineries and atomic energy plants.

The crucial role in making India self-sufficient in food was played by Punjab. The state became India’s bread-basket. Sizeable government investment in developing irrigation schemes and rural infrastructure during the 1950s, combined with the robust inputs of the Sikh peasantry, produced per acre yields which put Punjab far ahead of other states. Its wheat output increased from 1 million (metric) tons in 1950–1 to 11.5 million tons in 1989–90, rice—which had scarcely been grown there previously—from 0.1 to 6.7 million tons, and cotton from 132,000 to 417,000 tons in the same period. No less impressive were increases in other sectors like animal husbandry and dairying. One economist recently put Punjab’s current share of total wheat and rice production in India at 70 to 90 per cent and 60 per cent respectively.

Whilst Punjab’s spectacular agricultural achievements owe a great deal to major government investments, a similar concern was lacking when it came to funding its industrialization. No large state-sector plant was located in Punjab, in marked contrast to the extent to which other states in India were allocated these. At first Punjab’s exclusion was viewed as a lapse which would soon be set right, but gradually the pattern was discerned: Punjab was being denied the opportunity to industrialize. Why? New Delhi’s argument that the state’s proximity to Pakistan would make key industries vulnerable to attack did not allay suspicions, but increased them instead, especially since Pakistan showed no qualms about locating industries on its side of the border.

There is a view which holds that, though unwittingly, Punjab’s development, in continuing to lay emphasis on agriculture, on dairying, animal husbandry and cash crops, has provided a growth model in which the balance between a large agricultural sector and small and medium industries has succeeded in ensuring ecological safeguards even as a large agro-industrial base was being created. Instead of one or two heavy industries becoming the hub of all industrial activity in the state, this argument goes, Punjab’s balanced development is evenly spread within its borders.

Punjab has in fact industrialized—with small-scale enterprises accounting for a substantial portion of its overall production: about 40 per cent of output and almost 80 per cent of employment in 1989–90. Manufactures range from agro-processing industries to engineering goods, hand-tools, sewing machines, bicycles, textiles, knitwear, hosiery and sports goods. Their quality is excellent, turnover impressive, and exports sizeable. Credit for their success goes to the entrepreneurial drive and spirit of Punjab’s people, including those who came as refugees. With only 2.5 per cent of India’s population, Punjab accounts for more than 8 per cent of India’s small-scale industries.

Although it is no one’s case that the small-scale sector in Punjab has not been helped by government concessions and other incentives, the state has been denied facilities for full-scale industrialization, when Punjab’s rural youth—rendered surplus by mechanization of farming—might have been provided with opportunities to develop a scientific temper and technological orientation. Even more galling to Punjabis was the fact that considerable sums of money deposited by agriculturists and others in nationalized banks in the state were being invested elsewhere in India, in preference to investing them in the state’s industrial development. The Sikhs were not convinced by the argument that Punjab’s per capita income of 7,674 rupees (for 1989– 90) was far higher than the 4,291 rupees for the rest of India. Per capita incomes, they countered, would have been twice the present levels had the state been treated more even-handedly.

These and many other factors, mostly political but with communal undertones, would greatly add to the Sikhs’ disillusionment with New Delhi, whose unconcern at their increasing alienation, despite mounting evidence of the dangers involved, would take India to the brink of disintegration. New Delhi’s mishandling of the Punjab situation epitomizes the pursuit of policies contrary to the national interest—threatening the Republic’s very existence soon after the end of foreign rule.

At first light of dawn on a cool and clear morning in November 1966, the people of Punjab awoke to an unpleasant reality: their state had been truncated three ways—by the carving of two new states, Haryana and Himachal Pradesh, out of it.

Partition of their homeland was nothing new. But whilst Punjab’s 1947 division had taken place under the tutelage of an alien power, the second had been effected by the government of a free India. Startlingly similar considerations had triggered these momentous events.

The agenda of the colonial power was naturally different. Britain saw its self-interest served by a divided subcontinent. Two neighbouring nations, mutually hostile and embittered, are more easily managed to a former colonial power’s advantage than a single, strong state whose manpower, size, vast resources and political unity would make it less amenable to outside pressures or wilful persuasion.

While Whitehall’s interest in India’s partition and the creation of Pakistan was understandable, the events of November 1966 in Punjab were less so. Why was this viable state slashed into three whilst Uttar Pradesh, seven times its size, was left undisturbed? Why did it take thirteen years after the formation of the first linguistic state, Andhra Pradesh, to grant Punjabi-speaking people statehood? And why was the State of Punjab whittled down to a size unworthy of its energetic people?

The response to these questions by the ruling Congress Party has invariably been that since the issue was a particularly complex one, it took thirteen years to resolve. The truth is that the delay was deliberate prevarication. But why should the government prevaricate with a people who had suffered so much at Partition, who had made Punjab India’s bread-basket, and been a formidable bulwark in the nation’s war-prone relations with its northern neighbour, Pakistan? Perhaps the answer lies in the Brahminical élite’s ongoing determination to oversee India’s destiny, as it has done in varying degrees for millennia.

Being numerically few seems greatly to have influenced the political strategies of both the Brahmins and the British. The British, for instance, were never more than 60,000 in the entire subcontinent, which even at the time of the first census in 1881 had a population of 253 million. The pre-eminent Brahmins are barely 3 per cent of India’s population. Whilst India’s Partition appears to have been a reflection of Britain’s desire to maintain some kind of remote-controlled sovereignty over the divided subcontinent, the reorganization of its states after Independence also appears to reflect the Brahminical élite’s strategy of controlling India. The exercise of power, it is obvious, requires conditions to be created which make it easier to maintain the hegemony of the few.

Notwithstanding its populist appeal, the reorganization of provinces on linguistic lines was a folly whose damaging effect on India’s social fabric has yet to be fully analysed. The idea, although aired earlier, had been given specific form in 1920 when the Congress Party reorganized its provincial committees on the basis of language. Within nine years Motilal Nehru, Jawaharlal’s father, committed the Congress to a linguistic reorganization of India after Independence, and spelt it out in the Nehru Report. In 1945 Dr. Pattabhi Sitaramayya, president-elect of the All India Congress Committee, reiterated his party’s pledge to this goal.

There were second thoughts after the transfer of power. As practical considerations outweighed hidden agendas and populist pledges, some began to see more clearly the danger of letting linguistic chauvinism loose on a fledgling republic. There was a keener awareness, in a section of the Congress, of how language bigots could compromise national unity. Despite Jawaharlal Nehru’s own apparent opposition to a type of reorganization that his father had recommended decades earlier, the ill-advised decision to divide the country linguistically was taken.

As the time for the execution of the reorganization neared, a pattern of double standards emerged. The two committees—one appointed by the government and the other by the Congress—which had been established after Independence to report on linguistic reorganization each endorsed the idea of other language states, but excluded the northern states from it, especially Punjab. According to the government commission chaired by S.K. Dar, which submitted its report on 10 December 1948, “nationalism and sub-nationalism are two emotional experiences which grow at each other’s expense,” and the reorganization of India on “mainly linguistic considerations is not in the larger interests of the Indian nation.” But after this evaluation, the Dar Commission equivocated, calling the reorganization “a grave risk, but one that had to be taken.” Despite its own concerns, why did the Commission’s report recommend the formation of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Maharashtra on linguistic lines? And why did it exclude Punjab? The Commission observed that “oneness of language may be one of the factors to be taken into consideration . . . but it should not be the decisive or even the main factor.” The Brahmin in Mr. Dar may have got the better of him.

Equally striking were the Congress Linguistic Provinces Committee’s findings. Its members, Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabhbhai Patel and Pattabhi Sitaramayya (two of whom were Brahmins), expressed grave reservations about the party’s earlier commitment to linguistic provinces as they would create “mutual conflicts which would jeopardize the political and economic stability of the country.” Then, curiously, their report of 1 April 1949 went on to state that “we are clearly of the opinion that no question of rectification of boundaries in provinces of North India should be raised at the present moment, whatever the merit of such proposals might be.” If merit was not a criterion, what was? Politics, not principle.

Even before Indira Gandhi became prime minister, she was against the Centre (the Federal Government in New Delhi) conceding the demand for a Punjabi-speaking state: “to concede the Akali demand would mean abandoning a position to which it [the Congress] was firmly committed and letting down its Hindu supporters in the Punjabi Suba [i.e., a Punjabi-speaking state].” According to Hukam Singh, the speaker of parliament, himself a Congressman and a man held in high regard by everyone, “Lal Bahadur Shastri continued the policy of Jawaharlal Nehru, and was as dead against the demand of Punjabi Suba as was Nehru . . . Nehru stuck to it. Shastri continued the same, and Indira Gandhi has made no departure.” So when a suba was conceded it was a mockery of what Punjab had once been.

If politics, then, was the criterion, it is easier to understand the denial of a linguistically reorganized Punjab to the Punjabis and Sikhs, and its exclusion from the Dar Commission’s terms of reference. The activities of various Hindu fundamentalist organizations and groups had much to do with it, for they had gone about persuading their co-religionists in Punjab to disown Punjabi as their mother tongue, the language Punjabi Hindus had spoken for generations. Long before reorganization the ground had been gradually prepared for Punjab’s Hindus and the underprivileged castes to declare Hindi their mother tongue. The timing of this campaign—on the eve of the 1951 census in Punjab—was significant since the census figures would decide who spoke which language and provide the eventual justification for carving what were in fact two Hindi-speaking states out of Punjab. The man who orchestrated these moves, Lala Jagat Narain, was not only a staunch Arya Samajist but also the general secretary of the Punjab Congress Committee. He epitomized the marriage of convenience between Congress ambitions, religious intolerance and sectarian politics.

New Delhi manipulated the media and public opinion to project a Punjabi-speaking state as a demand for a separate Sikh state. Inevitably, a purely linguistic demand, which other language groups had also made—and been granted—and which the Congress Party had declared as its goal in 1929, was in Punjab’s case labelled a separatist demand. The media, ever eager to write of dark plots where none exist, willingly accepted the idea of the Sikhs as separatists and converted a linguistic demand into a confrontation between two religious communities. The Sikhs, without media of their own, were in no position to present their side of the case.

Several facts were not revealed to the public. The Sikhs in their representation to the States Reorganization Commission had pressed for a unilingual Punjab, the Hindu population of which would be 57 per cent as against 43 per cent Sikhs. Their demand in effect was not for a Sikh but for a Hindu majority state. But it would be a Punjabi state. The Commission rejected the proposal because it was not supported by Punjab’s Hindus. For the Congress had seen to it that it would not be. Being in power in New Delhi and most states, it was in a position to do so.

It was ironic that in 1906 the Muslims, a minority, had asked the British for separate electorates in order to separate from the Hindu majority, while in independent India the Hindu majority of Punjab wanted to be separated from the Sikh minority! Such segments of Punjab’s Hindu society were the real separatists.

Almost forty years after the Dar Commission’s report, the Commission on Centre-State Relations (Sarkaria Commission) had this to report on the impact of linguistic reorganization of the country. “There has been a growth in sub-nationalism which has tended to strengthen divisive forces and weaken the unity and integrity of the country. Linguistic chauvinism has also added a new dimension in keeping people apart . . . unless there is a will and commitment to work for a united country, there are real dangers that regionalism, linguistic chauvinism, communalism, casteism, etc., may foul the atmosphere to the point where secessionist thoughts start pervading the body politic.”

A glance at the governance of Punjab in the ten years preceding Independence will provide a useful footnote to these intrigues. Indians tend to believe that the British devised the policy of divide and rule. This is questionable. The Brahmins perfected it long before the British, who in all likelihood took their inspiration from them. Of course the British divided different religious, caste, class, regional and language groups, whenever and wherever they could. But divide and rule was never a constant, just one of many strategies by which they safeguarded their Indian empire. Their Punjab policy in the years prior to Partition proves it.

British policies of that period were based on pragmatic and hard-headed considerations. Since a coalition of different communities at that time gave stability to Punjab, which served British interests, it was encouraged. The astonishing degree of political equilibrium, in a religiously divided state, under the Unionist Party from 1937 to 1947 would not have been possible without the active encouragement of the British, or without their full support for two successive state premiers of impressive stature. Since both Sikander Hayat Khan and Khizr Hyat Tiwana’s pluralistic approach to the state’s three powerful communities, the Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs, helped to ensure stability in the northern reaches of Britain’s Indian Empire, decisions affecting their province were left to them.

Whilst the British encouraged a stable and unified Punjab, the Indian leadership preferred a segmented one after Independence. By reducing it to a size which entitled it to only thirteen members of parliament out of 545, it considerably diminished Punjab’s importance in New Delhi’s corridors of power. It remains inexplicable to the Sikhs why a strong and united Punjab was viewed as a threat to the ruling party in Delhi. An increasing number attribute it to their high profile in the Indian army; their individualistic and independent temperament; their fierce pride in their religion. They also realize that Sikhism’s break with its Hindu origins centuries ago continues to be viewed with disfavour by the unforgiving elements in Hindu society, and also suspect that there could be an underlying fear in the minds of the ruling mandarins that, like the traditionally militaristic Junkers of East Prussia, the Sikhs too might one day prove difficult to control and therefore have to be cut down to size by all means possible. This, in effect, was achieved by encouraging breakaway demands of two sizeable Hindu constituents of the state of Punjab, which also helped disperse large numbers of Sikhs beyond its borders.

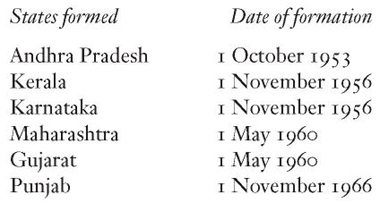

There is still more to the story of Punjab’s agony. After the principle of one language for one state had been incorporated in the States Reorganization Act of 1956—with Punjab and Bombay excluded as bilingual—Bombay was reorganized on 1 May 1960. In its place the Marathi- and Gujarati-speaking states of Maharashtra and Gujarat emerged. But it took six more years for a Punjabi-speaking Punjab to be formed, and that too after a bitter struggle, in which many Sikhs died, thousands were jailed, and the entire community registered the distressing fact that political clout and not principle would influence decisions in Independent India. Proof of this was provided by the time-table for redrawing state boundaries:

The 1961 census figures, which determined the areas to be included in truncated Punjab, were as mischievous as those of its predecessor, the 1951 census. Thus several Hindu-majority areas where Punjabi had always been spoken—but disowned in the census—were left out. Even Chandigarh, the city designed by Le Corbusier and built as the new capital of Punjab after Partition, was made a Union Territory to be directly administered by New Delhi. In the end, what was conceded was not a genuine unilingual Punjabi-speaking state with 57 per cent Hindu population as desired by the Sikhs, but a communal Punjab they had never asked for.

Aside from the encouragement of xenophobic tendencies, lack of vision in India’s linguistic redistribution is also evident from the territorial and river waters disputes which have plagued the country ever since Partition. Among the many that continue to simmer and boil over from time to time, with the ever-present danger of still deadlier confrontations, are the sharing of Cauvery river waters between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, the Krishna river dispute between Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh, the Telegu Ganga canal project between Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, and the river waters and territorial disputes between Punjab and Haryana.

When to these avoidable conflicts are added the founding of political parties whose chief raison d’être is to harass and hound migrants from other states, the cost in ruined lives, to a nation divided against itself, is incalculable. Bombay’s Shiv Sena party is a classic example of what crude political demagoguery has done to India’s once premier city. Its increasingly inflammatory agitation even after the formation of a new linguistic state was based on the premise that Maharashtrians were being sidelined for jobs in their own state. After Shiv Sena’s creation in 1966, it appealed to Maharashtrian chauvinism by attacking South Indians settled in Bombay. Not unexpectedly, this helped the Sena’s political prospects, but proved disastrous for Bombay’s South Indians. Worse still, encouraged by its stifling stranglehold over the once uniquely cosmopolitan and liberal city, the Sena turned on the Muslims and in a vicious killing spree in December 1992–January 1993, massacred over 1,500 in cold blood, with the connivance of a partisan police force. Religious persecution, the Sena found, provided more political mileage than xenophobia, and also bettered its prospects of emerging as an all-India party.

But even the Janus-faced approach of the Indian government to Punjab did not erode communal relations in that state. After the dismemberment of the state in 1966 the Sikhs did not turn on the Hindus, nor try to drive them out, nor resent their economic prosperity. But their indignation against New Delhi’s injustice was palpable because Punjab’s political clout in the polity of India had been deliberately reduced, and its demands were trifled with. Many Sikhs for the first time doubted if they had any future at all in a Union which so disregarded their interests. It had communalized Punjab’s politics, created a climate of cynical indifference to principles of equity and transparency in government, and preferred political expediency to moral integrity.

Attitudes influence events, and New Delhi’s attitude proved catastrophic. In the early 1970s the Akali Dal, the foremost political party of the Sikhs, which had earlier rejected religious rhetoric, changed its stand. Its new message: the Sikh Panth, or faith, was in danger. This heady refrain was far from the truth. A faith like the Sikh, whose adherents are deeply committed to it, cannot easily be endangered. But as communal-religious elements were now to the fore, the Akali Dal Party went along with them. Its members also showed a singular incapacity to identify themselves with the cause of the minorities all over India, especially the Muslims and Dalits who have suffered the most from the chauvinism of India’s ruling élites. Had they assiduously built up a position of ideological integrity, as the founders of their faith and others after them did, they would not have been as isolated as they were in the 1980s.

In the 1970s, the Akalis’ inability to win political power at the polls also contributed to their religious bellicosity. Their political sloganizing achieved nothing more than polarizing Hindus and Sikhs and projecting Sikhs in an unflattering light. Given the powerful ties of the Sikhs with their faith, it was altogether unbecoming to imply that the Panth was in danger. The dignity of an indestructible faith and a proud people was needlessly compromised.

The Akali defeat in the 1972 provincial assembly elections was due to a woeful lack of pragmatism and purpose in electoral politics, even within the state. Instead of winning voters’ confidence through a constructive blueprint for Punjab’s industrialization, power generation, communication networks and administrative revitalization—which would have been bound to appeal to the state’s practical-minded electorate—the Akalis responded to Congress manipulations by playing the religious card. This was unwise, whatever the short-term appeal.

Hindu-Sikh relations had suffered many strains in the past. The Arya Samaj and Hindu Mahasabha’s denigration of Sikh philosophy and scriptures, while gaining them an impressive following in urban Punjab, had adversely affected Hindu-Sikh cohesiveness. Yet these strains, not very dissimilar to those experienced by other societies, had been kept in check. The reorganization of the Indian states, however, proved more destructive since it played politics with explosive issues like religion and language.

Ironically, when the Akali policy-makers pulled themselves together, it got them nowhere. In 1977 they put forward a wise and far-sighted proposal which could have benefited the entire country since it went beyond the politics of religion and language. The Anandpur Sahib Resolution was passed by the Akali Dal at its General Session attended by over a hundred thousand persons at Ludhiana on 28–29 October 1977. The first and most important of its points spelt out the main thrust of the document:

THE SHIROMANI AKALI DAL REALISES THAT INDIA IS A FEDERAL AND REPUBLICAN ENTITY OF DIFFERENT LANGUAGES, RELIGIONS AND CULTURES. TO SAFEGUARD THE FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS OF THE RELIGIOUS AND LINGUISTIC MINORITIES, TO FULFIL DEMANDS OF DEMOCRATIC TRADITIONS AND TO PAVE THE WAY FOR ECONOMIC PROGRESS, IT HAS BECOME IMPERATIVE THAT THE INDIAN CONSTITUTIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE SHOULD BE GIVEN A REAL FEDERAL SHAPE BY REDEFINING THE CENTRAL AND STATE RELATIONS AND RIGHTS ON THE LINES OF THE AFORESAID PRINCIPLES AND OBJECTIVES.

The Resolution went on to point out that at the time of the Emergency in June 1975 the principle of decentralization of powers advocated by the Akali Dal Party had been openly accepted and adopted by other political parties of all hues, including the Janata Party, CPI(M), ADMK, etc. It endorsed “the principle of state autonomy in keeping with the concept of federalism,” and urged the government to

RECAST THE CONSTITUTIONAL STRUCTURE OF THE COUNTRY ON REAL AND MEANINGFUL FEDERAL PRINCIPLES TO OBVIATE THE POSSIBILITY OF ANY DANGER TO NATIONAL UNITY AND THE INTEGRITY OF THE COUNTRY AND FURTHER TO ENABLE THE STATES TO PLAY A USEFUL ROLE FOR THE PROGRESS AND PROSPERITY OF THE INDIAN PEOPLE IN THEIR RESPECTIVE AREAS BY THE MEANINGFUL EXERCISE OF THEIR POWERS.

The other points contained in the Resolution concerned river waters, social structures, discrimination in jobs, refugee rehabilitation, abolition of duties on farm machinery, accelerated industrialization, and so on. There was nothing unconstitutional or secessionist in any of them.

The distinguished jurist, retired Chief Justice R.S. Narula, commented in the 1980s: “The only way to save the country from disintegration is to accept and adopt the Anandpur Saheb Resolution for the entire country—for every state unit of India.”

But the Resolution was attacked as a secessionist document which would threaten the unity of the country and lead to an independent Sikh state! It was attacked not because it threatened the unity of the country, but because it threatened the hegemony of the Congress Party, which, during its years in office, dismissed state governments 59 times by invoking Article 356 of the Constitution which gives powers of dismissal to the Centre. Since federalism would loosen New Delhi’s control over the states, its mandarins, especially through the press, bitterly opposed it. Declared The Hindustan Times, the capital’s leading daily: “Needless to say this would not only upset the Centre-State balance visualised in the Constitution but strengthen regional pulls to the detriment of national unity.” The paper completely ignored the fact that the Resolution was along the federal axis, in favour of state autonomy, and against the Centre’s hegemony.

The malevolent attacks against the Akalis and their Resolution in all general media suggested one of two things: either the government’s short-sightedness was bordering on incurable blindness, or the ongoing and deliberate alienation of the Sikhs was part of a larger game plan. Certainly, an explosive situation was being created which could get completely out of hand. Which is exactly what happened.

The delay in granting Punjab statehood, its truncated size when it was granted, the subterfuges behind the language controversy, the attack on the Anandpur Sahib Resolution, were tragic milestones which saw the Sikhs—reluctantly and against the wishes of their majority—move away from the national mainstream. Each sleight-of-hand left the Akalis and much of Sikh opinion frustrated; each heightened religious rivalries still further.

Rajni Kothari, a respected political thinker, saw the larger import of what was happening: “By turning the Punjab issue into a Hindu-Sikh confrontation and interpreting the demand for regional autonomy as essentially one for secession based on a religious challenge, the ground was laid for communalizing not just the politics of Punjab but of the country as a whole. Punjab became a ‘pivot’ from which the country was spun into a new communal orbit.” (Kashmir was next in line; there the duly elected Farooq Abdullah was sent packing and Congress communalized the politics of that state too.)

In June 1975 the Sikhs had once again identified themselves with a matter of grave national concern when they fielded the most sustained resistance to the Emergency declared by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in June of that year. Under the direction of Sant Harchand Singh Longowal, over 40,000 Akali workers were jailed for their “Save Democracy” movement against this lawless act of the Congress-led Union Government. These people were the only ones in India to oppose the Emergency on such a scale. Mrs. Gandhi never forgave the Akalis their resistance and, as events were to show, she had a very long memory.

What was the Emergency about? It followed a judgement delivered on 12 June 1975 by Justice Jag Mohan Lal Sinha of the Allahabad high court, unseating Mrs. Gandhi from parliament. The judgement, delivered on a petition by one of her political opponents, accusing her of corrupt campaign practices, also debarred her from any elective office for six years. After some hesitation, Mrs. Gandhi rejected the judgement. Since this was impracticable in a country with a constitution and rule of law, she suspended both. Through a Proclamation of Emergency signed by a pliant president of India at 11:45 p.m. on 25 June 1975, India’s democratic pretensions ended. Within minutes of the signing of the Proclamation, security forces were on the move across the country and over 100,000 persons including former cabinet colleagues, opposition leaders, members of parliament, journalists, academics and students were arrested. Stringent censorship came into effect, society was terrorized, political prisoners were often manacled, and midnight knocks became customary. When lawyers of the Delhi High Court Bar Association protested, over a thousand lawyers’ chambers were demolished by bulldozers.

In keeping with India’s ongoing Brahminical tradition, Indira Gandhi, from her number two position of power as prime minister, ensured that the president, as head of state, signed a decree which suspended India’s fledgling democracy for almost two years.

The Emergency was one of Independent India’s bleakest watersheds. It set the stage for a climactic showdown which witnessed the Indian army’s assault on one of the most revered places of worship in the world, a prime minister’s assassination, the massacre of thousands in the nation’s capital, and the danger of the Republic’s dismemberment.

In the snap general elections called by Mrs. Gandhi in March 1977, she was defeated, and a coalition government brought to power which restored most of the freedoms she had taken away. But a person like Indira Gandhi is not easily kept out, even less so in this case since the men who succeeded her soon found themselves in the grip of that fatal Indian malaise, factionalism. With no lessons learnt from the past or present, they were soon plotting each other’s downfall. The opportunities their infighting presented were not lost on her. Drawing on her formidable manipulative skills, she engineered a revolt within the coalition which led to the ousting of the prime minister and then of his successor, to be followed by the dissolution of parliament and the announcement of general elections. Her convincing win in January 1980 once again saw her installed as prime minister.

While Indira Gandhi was making her moves to bring down the coalition government, she was also planning the opposition government’s downfall in Punjab. If Punjab’s ruling coalition of Akalis and the right-wing Hindu party Jan Sangh provided hope in the state’s communally strained internal relations, it mattered little to the Congress. Its own goal was to unseat the state government by undermining the conciliatory Akalis, because Indira Gandhi had scores to settle with them for defying her Emergency. If the Sikhs were thus alienated still further, that was fine by her; she was willing to sacrifice their limited vote in parliament for the considerably larger Hindu vote.

Her chillingly self-serving plan called for a spellbinding Sikh who would mesmerize his co-religionists with oratorical skills, convince them of the existence of a threat to their faith, and wean them away from the moderate Akalis. Should the latter arrest him for inciting religious passions, it would antagonize the main body of the Sikhs and weaken the Akali support base, since they would appear vindictive towards a man of God. If they did not arrest him, the leaders of the Akali coalition government would antagonize their Hindu partners. And because it is difficult to manage such contradictions indefinitely, the state government would surely fall.

The person chosen for the role was Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, a seminary preacher with a considerable knowledge of the Sikh scriptures. Seen at the outset as a devout Sikh and a man of God, he was built up—without his knowledge—with all the Brahminical subtlety and skill perfected over millennia into a charismatic leader who eclipsed the Akalis by utterances more fiery than their own; whose larger-than-life image was repeatedly projected through cannily manipulated press, radio and television. It came to appear as if he represented the aspirations of all Sikhs, though millions of them had no interest in him or in the Akalis. Significantly, the government did not apprehend him as long as he lived outside the Golden Temple complex. But after he had served the Congress purpose—of communalizing Punjab’s politics—and had moved into its sacred precincts on 15 December 1983, the final gory scene was enacted in a carefully conceived political move which required the Indian army to unleash its firepower against the Golden Temple.

In the New Year the Akali leaders, tired of getting nowhere with the Congress for any of their demands by their usual moderate means, decided to perform a symbolic gesture of protest: to burn a page of the Indian Constitution in public. Efforts were made to dissuade them from this act, but too late. The danger was acute: the government’s Machiavellian policy of blurring public perception of the distinction between the moderate Akalis and the firebrand it had so assiduously built up was now crowned with success in the fusion in the public mind between the Constitution-burning Akali leaders and the inflammatory utterances of Bhindranwale. As “Sikh extremists” became a catch phrase not only in India but around the world, the Sikhs were seen as a threat to community relations, a threat to the peace. And in taking sanctuary in the Golden Temple complex, Bhindranwale was departing from Sikh historical precedent by placing the supreme shrine of Sikhism in the line of fire.

Images of tanks rolling into the hallowed environs of the Golden Temple in June 1984 are engraved in the minds and hearts of all Sikhs. Their ostensible purpose was to flush out Bhindranwale. The use of massive power, resulting in the complete destruction of the Sikh seat of temporal power, the Akal Takht, and the loss of 5,000 civilian lives— for an entirely unconvincing purpose, simply to apprehend a “handful of men”—stunned Sikhs the world over; that it was done to improve the Congress Party’s election prospects and enable Indira Gandhi to claim she had saved the nation from Sikh “secessionists” was no less astounding.

The consummation of the course of vitriol and violence was still to come. On the morning of 31 October 1984, less than five months after the assault on the Golden Temple complex, Indira Gandhi died at the hands of two Sikh bodyguards in her security detail. Before the day of her assassination ended, innocent Sikh men, women and children in Delhi, Kanpur, Bokaro and many other cities in northern India had already lost their lives. Encouraged by central government ministers and members of parliament, with mobs assembled by them, and with the connivance of the capital’s police, a four-day orgy of reprisal killing and plunder in the national capital was underway. Eyewitness reports identified Congressmen and police personnel directing and often leading the killers in different areas of Delhi in which, by government’s own admission, 2,733* persons were killed or burnt alive in those four days. The Sikhs dispute this official figure—which includes neither the “missing” nor unreported deaths nor bodies found in trains pulling into Delhi, nor those murdered and thrown out of moving trains.

The depravity of those days is starkly evident from case histories.

Hazara Singh and his three sons, Kulwant Singh, Jagtar Singh and Harmit Singh, with their families, lived in a two-storied house in Hari Nagar Ashram, New Delhi. They had built a business as electrical contractors and worked for clients like the Oberoi Hotel, Hyatt Regency and the Delhi Development Authority. On the morning of 1 November 1984, they found their house surrounded by a mob. Their new Ambassador car was set alight and the front part of the house looted. The family, caught unawares and unarmed, remained trapped in the rear room from 10 a.m. till 10 p.m., hoping against hope for police help. The police did finally come, and this is how the subsequent plaint in the high court civil suit filed for damages described their visit. (The defendants have denied the allegations and the case has not yet come to trial.)

LATER, DEFENDANTS NO. 11 TO 13 [THE STATION HOUSE

OFFICER AND SUB-INSPECTOR AND ASSISTANT SUB-INSPECTOR

* The Citizens’ Justice Committee places this figure at 3,870.

OF POLICE . . . ], ALONG WITH A POSSE OF ARMED POLICEMEN, CAME TO THE SPOT IN A POLICE VEHICLE. THEY WERE IN UNIFORM. AFTER GETTING DOWN FROM THEIR OFFICIAL VEHICLE, THEY FIRST TALKED TO DEFENDANTS NO. 1 TO 10 AND SOME OTHERS IN A FRIENDLY MANNER . . . THEN SHOOK HANDS IN A MOST FRIENDLY WAY. MOST OF THE DEFENDANTS . . . [THEN] JOINTLY RAISED THE SLOGAN “KHOON KA BADLA KHOON” [MEANING “BLOOD FOR BLOOD”] . . .

At around 10 p.m., the defendants Nos. 1–10 mentioned in the plaint poured kerosene oil through ventilators in the rear of the house and set it alight. The first to come out was Hazara Singh, who with

. . . FOLDED HANDS [ASKED THE CROWD] TO SPARE THE LIVES OF HIS HELPLESS FAMILY AS THEY WERE ABSOLUTELY INNOCENT. THEREUPON SOMEONE FROM AMONGST THE DEFENDANTS . . . [MOST OF THEM WERE ARMED WITH DAGGERS, SWORDS AND IRON RODS] SEVERED BOTH THE FOLDED HANDS OF HAZARA SINGH WHICH DROPPED DOWN. THE SAID DEFENDANTS ALONG WITH THE ASSOCIATES THEN ATTACKED HIM WITH IRON RODS.

Hazara Singh’s three sons were also set upon. The plaint reads on:

AFTER MAKING A HEAP OF THE HALF-DEAD ADULT MALE MEMBERS [OF THE FAMILY], ALL OF THEM WERE DOUSED IN KEROSENE OIL AND SET ON FIRE. DEFENDANTS NO. 1 AND 10 DANCED AROUND AND CELEBRATED THE BONFIRE IN A VERY GAY MOOD.

Left bereft and bewildered, the plaintiffs who are the survivors of this massacre include widows of two of the sons with four young children in all and Hazara Singh’s nineteen-year-old unmarried daughter. Not one of the accused named in the plaint has been criminally prosecuted for the murder of Hazara Singh and his sons aged 27, 23 and 20, indicative of the extent of the Indian judicial system’s neglect in delivering justice in these crimes.

Mrs. Doban Kaur, of Sultanpuri, New Delhi was watching television with her family on the afternoon of 1 November 1984 when a mob of about 2,000 surrounded their house. In her affidavit before the government-appointed, one-man Misra Commission she narrates what happened:

THEY BROKE DOWN THE DOOR AND ENTERED THE HOUSE. SOME PEOPLE HAD STICKS AND RODS AND SOME HAD PISTOLS. SOME PEOPLE PRESSED A PISTOL AGAINST MY CHEST AND THREATENED TO SHOOT ME IF I DID NOT GO OUT. I WENT AND STOOD OUTSIDE. SOMEONE WAS HOLDING ME. MY SON WAS ATTACKED WITH A STICK AND THEN HE WAS BURNT ALIVE. MY BROTHER-IN-LAW WAS ALSO KILLED AND TAKEN OUT OF THE HOUSE AND BURNT. MY FATHER AND [FOUR] BROTHERS [AGED BETWEEN 7 AND 30] WERE ALSO BADLY BEATEN AND THEN BURNT ALIVE . . . THE HALF BURNT BODIES WERE PUT INTO GUNNY SACKS . . . AND TAKEN AWAY . . .

The experience of Gurbachan Singh and his friends, residents of a housing estate at Kalyanpuri in Delhi, is a bizarre tale of a police force disarming Sikhs and facilitating their killing. But since—unlike most—they were aware of an impending attack, they fought back when a crowd of around 5,000 persons arrived on the morning of 1 November 1984. According to Gurbachan Singh’s deposition before the Misra Commission:

WE DIVIDED OURSELVES IN TWO GROUPS AND TRIED TO CONTAIN THE MOB ON BOTH ENDS OF THE STREET. THE MOB CAME A SECOND TIME AGAIN. THE POLICE, VERY MUCH A PART OF THE MOB, TOOK AWAY OUR GUNS AND LEFT. THEN THE MOB ATTACKED US . . . THE DEFENSE CONTINUED UP TO 6 OR 7 P.M. THE MOB AGAIN ATTACKED AT ABOUT 11 P.M. BUT COULD NOT REACH OUR COLONY.

The same story was repeated on 2 November when at about 6 a.m. an equally large crowd again attacked the colony and was resisted by around 40 Sikhs.

THEY CONTINUED TO ATTACK US TILL 11 A.M. BUT THEY COULD NOT INFLICT SERIOUS DAMAGE ON US. BUT AT ABOUT 11:30 A.M. THE POLICE ARRESTED SOME OF OUR MEN . . . THE MOB AGAIN CAME AT ABOUT 3 OR 4 P.M. OUR MEN TRIED TO DEFEND THEMSELVES AND DID NOT ALLOW THE MOB TO ENTER THE COLONY. AT ABOUT 5 P.M. POLICE CAME AGAIN AND SNATCHED [THE] LICENSED GUNS OF OUR MEN AND THEREAFTER THE MOB ARRIVED IMMEDIATELY AGAIN. PEOPLE OF THE COLONY DEFENDED THEMSELVES WITH STONES AND IT CONTINUED LIKE THIS TILL ABOUT 11 P.M. MOB ATTACKED, WE DEFENDED WITH STONES, MOB RETREATED, CAME BACK AGAIN. ON 3.11.1984 AT ABOUT 8 A.M. MOB CAME AGAIN, BY THIS TIME SOME OF OUR MEN WERE INJURED AND OTHERS WERE TIRED, STILL WE DEFENDED OURSELVES TILL 12 P.M. AT ABOUT 2 P.M. POLICE CAME AGAIN AND THEY THREATENED US AND ASKED US TO PROCEED TO OUR RESPECTIVE HOUSES. WE WENT TOWARDS THE GURDWARA TO SAVE OUR LIVES AND IMMEDIATELY THEREAFTER THE MOB STARTED LOOTING OUR HOUSES.

Hundreds of other such sworn depositions indict ministers, members of parliament, police officials, public figures and businessmen. Each tells a sordid story of how crowds of several thousands, abetted and encouraged by the administration, fell upon a few men, women and children and killed them in full view of the government of India. Could the violence have been prevented? Easily.

Soon after Mrs. Gandhi was shot on 31 October, the General Officer Commanding, Meerut, was asked by the Defence Ministry to dispatch an army unit to Delhi immediately, to deal with any contingency following the prime minister’s death. Realizing the seriousness of the situation, the GOC ordered a unit which had just returned from field exercises to move to Delhi even before it could unpack. The unit—the 15th Sikh Light Infantry (LI)—consisted of 1,600 soldiers and officers. Arriving at the capital’s border on the evening of 31 October it was stopped there for several hours—for reasons unknown—before finally reaching its barracks in the cantonment at 11 p.m. It took up its duties on the morning of 1 November under the command of Major J.S. Sandhu, a Sikh officer.

Through intensive patrolling in the section of Delhi allotted to it, the 15th Sikh LI saved many lives, prevented looting and stopped the torching of businesses and houses. In the afternoon, while crossing the Safdarjung Development Area, Major Sandhu decided to investigate what from a distance looked like a house on fire. Before he and his men could enter the residential complex a man who identified himself as a senior intelligence officer tried to stop them. He said that the army had “no orders to intervene” and questioned the army’s presence there. Major Sandhu brushed aside his objections and when he persisted and blocked the road with his car, the major warned him that he would order his men to open fire if he didn’t remove himself at once. The man did. On seeing the military, the mob surrounding the burning house ran away, but a policeman on duty gave the information that the house was empty. Cries for help from within, however, told a different story. Fortunately, the army was able to rescue and remove the inmates to a safe place.

Within an hour or so of this, Major Sandhu was ordered to report back to Delhi Cantonment where he and his unit were confined to barracks. They stayed there throughout the duration of the killings in Delhi. Who withdrew the army on 1 November, just as violence was starting to escalate? Clearly the general commanding the Delhi Area gave the orders. But who instructed him to do so? Who was the intelligence officer whose report to the government led to the army’s withdrawal? No enquiry has revealed the answers. This point was driven home by a Delhi lawyer, Harvinder Singh Phoolka—who has persevered for years in his efforts to bring the guilty to book—in a recent letter to the Chief Minister of Delhi: “The people who are responsible for withdrawing the army which was patrolling the roads of Delhi on the morning of 1 November 1984—and effectively controlling the violence—and ordering this army unit consisting of 1600 soldiers and officers to remain confined to barracks, were to a large extent responsible for the flare-up of violence which assumed such great magnitude. These persons are liable to be brought to book and punished for their misdeeds.”

Had the army been kept in place, casualties would have been minimal. Was this Sikh LI unit withdrawn to facilitate the killings? And why wasn’t Major Sandhu’s unit replaced, a lapse which gave the mobs enough time to do their work with the tacit—and often active—support of the Delhi police? Phoolka insists that the category of people who paralysed the law and order machinery but “remained behind the scenes while taking such important decisions” must be treated as co-conspirators, “and tried for murder along with other accused.”

The government of New Delhi neither stopped the killings nor brought the killers to trial. Instead, it not only confined the Sikh LI to barracks but subsequently gave a false declaration both before parliament and the Misra Commission to the effect that no army units were available to it on 1 November. Even the report of the Misra Commission (of which more later) corrects this falsehood by recording the fact that the force was available to the government from early morning of 1 November.

Even as the world’s media, assembled in the capital in the aftermath of Mrs. Gandhi’s assassination, watched the horror unfold, the government allowed the blood-letting to continue. John Fraser in Canada’s Globe and Mail described how “for three horrific nights and four days, the violence was allowed to proceed . . . by which time the worst atrocities had been committed.” As for setting the wrong right, Fraser wrote that “hardly had the country recovered from Mrs. Gandhi’s death and the ensuing bloodshed when the Bhopal chemical disaster struck . . . While Mr. Gandhi [who succeeded his mother] is prepared for the most exhaustive inquiry possible to examine the Bhopal disaster, because the primary focus of culpability is on a US company, the Delhi atrocities . . . would inevitably point a devastating finger at his own party and at the dark side of Indian society.”

Which brings us to yet another aspect of these events. Heedless of the excesses, the battering India’s image was receiving abroad, and the brutality of the capital’s police force, the government ordered no commission of inquiry to investigate the events. Seeing its inaction, a group of individuals got together with the intention of making up for government’s indifference. This is how they explained their concern: “The mosaic of India’s varied people and cultures is the very foundation of its strength, but if the bond of mutual tolerance and respect is fractured by an orgy of violence against any community, the unity and integrity of the entire structure is gravely imperiled. Such is the situation which faces our country today.”

India’s former foreign secretary, Rajeshwar Dayal, was the driving force behind the setting up of the five-member “Citizen’s Commission” which was headed by the retired chief justice of India with the former foreign, commonwealth, home and defence secretaries of the government of India as its members. All of them non-Sikhs, their solidarity reaffirmed India’s founding principle of secularism which the Congress government had treated with contempt. The concern of right-minded Hindus and Muslims, and their efforts to uncover the truth, proved that the ruling party’s indecencies had not affected the country as a whole.

The government’s hostility towards the Commission was expressed in various ways. It refused to allow it access to official documents, and the prime minister and home minister declined to meet it. A note to “suggest preventive corrective and retributive action; and propose ameliorative measures to restore public confidence” sent to home minister P.V. Narasimha Rao was not even acknowledged by him. The same politician, who as home minister had not stopped the carnage, would in a few years become India’s prime minister.

In the preamble to its report published on 18 January 1985, the Commission noted: “The incredible and abysmal failure of the administration and the police; the instigation by dubious political elements; the equivocal role of the information media; and the inertia, apathy and indifference of the official machinery; all lead to the inferences that follow.” The report’s inferences and recommendations were buried by the government. As were other excellent reports like Who Are the Guilty? by the Peoples’ Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL) and the Peoples’ Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR), Truth about Delhi Violence by Citizens for Democracy, and 1984 Carnage in Delhi by the PUDR. When the latter filed a writ petition in Delhi High Court seeking the Court’s directions for the setting up of a judicial commission of enquiry into the events, government opposed the petition, which was eventually dismissed by a division bench of the Court on the ground that it was for the executive to take a decision in the matter.

The one-man Commission that was finally appointed—following a statesmanlike Punjab Accord (formally called the Memorandum of Settlement) reached between Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Sant Harchand Singh Longowal on 24 July 1985—fell just short of farce. To begin with the appointee, Justice Ranganath Misra, a judge of India’s Supreme Court, seemed conscious of the Congress government’s sensitivities. He was later appointed India’s next chief justice. His moves looked carefully considered. His attitude towards human rights groups who were representing the victims was not helpful. The Citizens’ Justice Committee (CJC) and the voluntary group Nagrik Ekta Manch who were allowed to participate, withdrew, complaining about the apparent arbitrariness of his procedures. The CJC, incidentally, was headed by a former chief justice of India with several retired judges, eminent lawyers and outstanding public figures on it.

Not only did the Delhi administration defend the accused before the Commission, but Congressmen—in and out of power—have even been accused of trying to obstruct justice. A Report of the Advisory Committee to the Chief Minister of Delhi has this to say of the affidavits for the accused: “Most of the affidavits in favour of the accused were cyclostyled in identical proformas on which only the particulars of the deponent were filled in by hand. Most of the deponents of these affidavits who were summoned by the Commission did not appear to support their affidavits. Some others who appeared disowned their purported affidavits.”

When the CJC wanted to cross-examine the persons who had filed these affidavits, Misra turned down its request, denying it also the right to take copies of such affidavits, to examine statements of witnesses summoned at the CJC’s request but examined in its absence, and to inspect records produced at the behest of the CJC. Protesting against the denial of these rights which it maintained was in contravention of some of the basic principles of law, the CJC withdrew from the proceedings.

The Government received the Misra Commission’s report in August 1986, and took six months to place it before parliament in February 1987, a full 27 months after the killings. A weak and vapid report, it let key Congress figures off the hook and characteristically recommended the setting up of three more committees: the first to ascertain the death toll in the riots, the second to enquire into the conduct of the police, the third to recommend the registration of cases and monitor investigations. The third committee spawned two more committees plus an enquiry by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI). When one of these two, the Poti-Rosha Committee, recommended 30 cases for prosecution including one against Sajjan Kumar, Congress MP, and the CBI sent a team to arrest him on 11 September 1990, a mob held the team captive for more than four hours! According to the CBI’s subsequent affidavit filed in court, “the Delhi Police far from trying to disperse the mob sought an assurance from the CBI that he [Sajjan Kumar] would not be arrested.” The CBI also “disclosed that [another committee’s] file relating to the case [against him] . . . was found in Sajjan Kumar’s house.” The MP was given “anticipatory bail while the CBI team was being held captive” by his henchmen.

Justice Misra became the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and after retirement chairman of the National Human Rights Commission; the accused MPs, except one, were again given Congress tickets to stand for parliament; one of them, H.K.L. Bhagat, became a cabinet minister; three accused police officers were promoted and placed in high positions. As for punishment of the guilty, only five persons were given the death sentence—still to be carried out—for the murder of 2,733 persons, around 150 persons were jailed, and none of the accused MPs and prominent Congressmen has been punished. The government has not conducted any investigation into the withdrawal of the Sikh Light Infantry on 1 November 1984.

The Sikhs, determined to see those they believe to be guilty punished, continue to press for justice although fully aware of the fact that in India too, as Solzhenitsyn wrote about his country, “the lie has become not just a moral category, but a pillar of the state.”

Troubled already by earlier discontents, to which was added the recent savaging of the Golden Temple complex, Punjab’s Sikhs heard with disbelief and rage the horror endured by their fellow-Sikhs in Delhi. It was tyranny such as they had always encountered and resisted. Out of a steadily increasing sense of outrage, militancy against a state unwilling to see Sikhs exist as Sikhs and the desire for a Sikh homeland (Khalistan) grew in Punjab. But the portents were ignored by Delhi’s politicians, by men lacking the vision and wisdom to foresee the damage this would do to the national fabric. Countless tragedies could have been avoided had wiser counsels prevailed. Though Sikh alienation started with the Arya Samajists’ war of words against them in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the real aggravations took place after Independence, during the heyday of the Congress Party.

More aggravations were to follow. After the formation of Punjab State in 1966, it has been asked to share its capital Chandigarh—built to compensate Punjab for the loss of Lahore—with Haryana, though every other state has its own capital. Even Chandigarh was made a Union Territory directly administered by Delhi. The sharing of river waters also became a bone of contention, despite the fact that Punjab literally means the “land of five rivers”; and as India’s granary it could ill afford the diversion of its waters elsewhere. The Sikhs perceived every act of denial as an affront to the concept of federalism, fair play and mutual trust, which drove them to seek alternatives.

For a while, following the bold initiative by Rajiv Gandhi and Harchand Singh Longowal, there was hope that violent alternatives would be avoided. The Punjab Accord provided the possibility of an end to the confrontation between the Central Government and the Akali Dal. However, in less than a month of the signing of the agreement, Longowal was assassinated and most of its provisions were sabotaged by Rajiv Gandhi’s advisors who were more interested in undoing the Accord than seeing it succeed. Unable either to see through their game or to ensure implementation of the agreements reached, the prime minister allowed his initiative to be derailed, and the momentum towards reconciliation which the Accord and the Punjab elections following it had generated was lost.

This failure fed Punjab’s burgeoning militancy, to which the government’s response was brutal policing. Instead of serious attempts to resolve genuine grievances, official communiqués announced the numbers killed daily, mostly through faked “encounters,” by trigger-happy policemen who hunted down innocent and guilty alike. Few were brought to trial and in the case of those who were, courts were seldom provided with convincing proof of their guilt. Police “interrogations” inflicted extreme forms of physical and psychic trauma on victims. Security agencies armed with extraordinary powers took away not only people’s rights and freedoms—in the name of fighting militancy—but also their right to life. The democratic system of accountability was subverted by allowing security forces to exercise powers which legally they were not supposed to possess, such as torture, blinding, branding, rape and murder. While democratic systems prohibit the executive from transforming its whims into the rule of law, Indian democracy frequently encourages it, even though Article 21 of the Constitution clearly states: “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.” In Punjab, the procedures stipulated by the statute book were treated with disdain.

Inderjit Singh Jaijee, co-founder and convener of Punjab’s Movement Against State Repression (MASR), in his Politics of Genocide, Punjab 1984–1994, has chronicled the state’s contempt for human rights in a series of case histories. The text of his compilation was given to Jose Ayala Lasso, Commissioner for the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, in November 1995 at Lasso’s request. Here are just three of the Punjab police’s many excesses listed by him:

GURDEV SINGH KAUNKE WAS A HARD-LINER AMONG SIKH POLITICIANS AND ENJOYED A REPUTATION FOR INTEGRITY AND HONESTY AMONG THE SIKHS. FOLLOWING THE RESIGNATION OF DARSHAN SINGH AS JATHEDAR [HEAD] OF THE AKAL TAKHT [THE HIGHEST TEMPORAL SEAT OF SIKH AUTHORITY] IT WAS WIDELY BELIEVED THAT HE WOULD BECOME THE LATTER’S SUCCESSOR. SEEING THE DEMAND FOR HIS APPOINTMENT AMONG THE COMMUNITY WAS GAINING GROUND, THE GOVERNMENT WAS FILLED WITH APPREHENSION AS A STRONG JATHEDAR HOLDING HARD-LINE VIEWS WOULD STRENGTHEN THE MILITANTS’ CLAIM TO LEGITIMACY AMONG THE SIKHS. HE WAS REPEATEDLY ARRESTED.

THE INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS ORGANIZATION WAS ABLE TO PIECE TOGETHER WHAT HAPPENED TO HIM [LATER] ON THE BASIS OF EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS (PUBLISHED IN THE INDIAN EXPRESS ON 17 JANUARY 1993). ON THE MORNING OF 25 DECEMBER 1992, A POLICE PARTY . . . PICKED UP THE JATHEDAR FROM KAONKE VILLAGE IN THE PRESENCE OF ABOUT 200 PERSONS. HE WAS THEN BRUTALLY TORTURED BY THE JAGRAON POLICE . . . AND KILLED ON THE NIGHT OF 1 JANUARY 1993. HIS BODY WAS THROWN INTO THE SUTLEJ NEAR KANIAN VILLAGE UNDER SIDHWAN BET POLICE STATION. IT WAS NEVER FOUND.

ON 29 AUGUST 1991, S.S.P. SUMEDH SINGH SAINI OF THE CHANDIGARH UNION TERRITORY POLICE NARROWLY ESCAPED DEATH IN A BOMB ATTACK WITHIN JUST A FEW FURLONGS OF HIS OFFICE IN THE CENTRE OF THE CITY. AT FIRST SUSPICION FELL WRONGLY ON A BABBAR KHALSA MILITANT, BALWINDER SINGH, WHO BELONGED TO JATANA VILLAGE IN ROPAR DISTRICT. (LATER IT WAS DISCOVERED THAT THE KHALISTAN LIBERATION FORCE [ANOTHER MILITANT ORGANIZATION] WAS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE BLAST.)

THE VERY NEXT NIGHT (30 AUGUST), THREE UNNUMBERED JEEPS CARRYING EIGHT OR NINE MEN EACH WENT TO JATANA VILLAGE AND KILLED BALWINDER’S 95-YEAR-OLD GRANDMOTHER, HIS MATERNAL AUNT, HER TEENAGED DAUGHTER AND HIS POLIO-AFFECTED INFANT COUSIN. THEY SET THE BODIES ON FIRE AND DEPARTED. THE ROPAR POLICE INITIALLY ATTRIBUTED THE MURDERS TO “SOME UNIDENTIFIED MILITANTS.”

ON THE AFTERNOON OF 21 AUGUST 1989, A PARTY OF BATALA POLICE (ONE WAS IN UNIFORM, FIVE OTHERS WERE IN PLAIN CLOTHES) PICKED UP GURDEV KAUR AND GURMEET KAUR, BOTH EMPLOYEES OF THE PRABHAT FINANCIAL CORPORATION, FROM THEIR OFFICE OPPOSITE KHALSA COLLEGE, AMRITSAR. MANY BYSTANDERS WITNESSED THE ARREST. THE WOMEN WERE PUSHED INTO THE VEHICLE AND WHISKED AWAY TO BATALA, ANOTHER DISTRICT ALTOGETHER. THERE THEY WERE TAKEN TO A MAKESHIFT INTERROGATION CENTRE WHICH HAD BEEN SET UP IN THE ABANDONED FACTORY PREMISES OF BEIKO INDUSTRIES. IT WAS 6 P.M.

GURDEV KAUR WATCHED S.S.P. GOBIND RAM BEAT A SIKH YOUTH WITH AN IRON ROD THEN HE SUDDENLY TURNED AND STRUCK HER WITH THE ROD ACROSS THE STOMACH. HE RAINED BLOWS ON HER STOMACH UNTIL SHE BEGAN TO BLEED THROUGH THE VAGINA. THEN GURMEET KAUR WAS BEATEN IN THE SAME WAY. GURDEV FAINTED BUT WAS REVIVED AND BEATEN AGAIN. THE TWO WOMEN WERE TAKEN TO THE BATALA SADAR POLICE STATION AT ABOUT 11:30 P.M. NEXT MORNING SHE [GURDEV] WAS TAKEN TO THE BEIKO FACTORY AGAIN. HER LIMBS WERE MASSAGED BUT THEN THE BEATINGS AND INTERROGATION WAS [SIC] RESUMED. GURDEV WAS RELEASED AT 4 P.M. ON 22 AUGUST ON THE INTERVENTION OF HER RELATIVE. AFTER SHE WAS RELEASED SHE EXPRESSED FEARS THAT GURMEET HAD BEEN KILLED.

GURMEET KAUR WAS ALIVE—BARELY. SHE WAS SHIFTED FROM BATALA TO GURDASPUR JAIL AND RELEASED. SHE WAS UNABLE TO STAND UP AND TOLD THE PRESS THAT SHE HAD BEEN FLOGGED AND BEATEN, HER LEGS WERE CRIPPLED BY ROLLERS, SHE HAD BEEN MOLESTED AND THREATENED WITH DEATH.

THE TORTURE OF THESE TWO WOMEN LED TO THE TRANSFER OF S.S.P. GOBIND RAM. (REPORTED IN THE TIMES OF INDIA, 27 AUGUST AND 5 SEPTEMBER 1989, AND PIONEER, 27 AUGUST 1989.)

AFTER THIS INCIDENT EVEN THE GOVERNOR OF PUNJAB, S.S. RAY, ADMITTED THAT SOME OF THE OFFICERS HAD BECOME SADISTIC.

The excesses were not one-sided. Resistance movements the world over have crossed acceptable boundaries in fighting for their rights and ideals, and Sikh militancy was no exception. Limits were crossed, criminals infiltrated the movement, innocents were killed, and extortionists had their day. The brutality of train and bus bombings— carried out by government vigilantes as well, to discredit Sikh militants—was reprehensible and in no way less bestial than extreme police behaviour. But everyday crime was also attributed to the Sikhs—as if the state were free of all crime except for the criminal activities of “terrorists!”

The word “terrorist” was deliberately misused in the aftermath of 1984 to erase all distinctions between militant protest, the struggle for freedom, religious nationalism and self-determination. By ignoring militancy’s motivations and projecting the entire Punjab struggle as terrorist-inspired, New Delhi found a raison d’être for state repression, but all this achieved was further agony for Punjab for over a decade and a half. It was a vicious circle in which the militants viewed the gun as their only option and the government saw greater firepower as the only response to it. Overlooked in the escalating violence and counter-violence was the fact that state repression reflected failure of statesmanship, the inability of political leaders to deal with dissent.

In her path-breaking book Fighting for Faith and Nation—Dialogue with Sikh Militants, the American anthropologist Cynthia Keppley-Mahmood of the University of Maine tries to identify what prevents people from understanding terrorism. “Until it becomes fully normal for scholars to study violence by talking with and being with people who engage in it, the dark myth of evil and irrational terrorists will continue to overwhelm more pragmatic attempts to lucidly grapple with the problem of conflict. Hysterical calls to condemn terrorism from a distance, to find better ways of technologically defeating terrorists as we find ourselves less and less capable of politically defeating them, are of a piece with the failure of imagination . . . There is a greater naïveté, and a greater danger, I suggest, in continuing to insist that physically exterminating terrorists is the way to eradicate terrorism. A lethal game of one-upmanship ensues which feeds the appetite for power on both sides and injures many innocent bystanders in the process. People build excellent careers in the counterterrorism forum, money is poured into the coffers of counterterrorism think tanks, yet more fresh new terrorists spring up every day.”

This is what happened in Punjab in the period following the events of 1984. Between outbursts against terrorism, snap judgements, applause for police excesses, and the actions of ambitious police officers who built their careers—and feathered their nests—in the name of fighting terrorism, India came close to disintegration. Government made a mockery of the principles which democracies swear by: transparent governance, respect for human rights, commitment to constitutional proprieties, and accountability. If militancy’s excesses lack justification—which they clearly do—the tyranny of institutions established to deliver justice lack it even more. Indian prime ministers, from Indira Gandhi to Inder Gujral, muddied the waters still further by launching a worldwide diatribe against terrorism through a series of joint communiqués with every conceivable head of state. Sikhs were made to appear as disturbers of the peace, the Indian state as the victim.

By acting like a petty dictatorship, the administration diminished the idea of a democratic India and showed itself incapable of living by civilized rules. To an extent sections of the Indian public were also culpable. Possibly because of their own insecurities and inability to understand the dangerous implications of a force operating outside the law, the middle class and mercantile community’s adulatory endorsement of ruthless police methods contributed to their growth. The glorification of police officers who took the law into their own hands helped to embed the canker of resentments so deep that its destructive emanations will be felt for a long time among countless Sikhs.

A former militant described to Keppley-Mahmood how he joined the freedom movement: “My parents were very much hurt by the attack on the Golden Temple. My father commented that he had four sons and that even if one of them should get sacrificed for the nation he would be proud that his family had contributed something. He said clearly that nobody guilty of any crime should be spared. But he also felt that at no cost should any innocent be killed. I decided to become involved in the freedom movement, and my house became a place of shelter for the guerrilla fighters . . . Later, when I came to a leadership position . . . I never had anybody fight for me who was not a devout Sikh.” Now resident in the United States, Charanjit Singh describes his experiences and baptism by fire in detail: the bloody shootouts with the police; arrests, rescues and escapes; the pain of seeing comrades slain; solidarity under fire and, finally, the irrelevance of life—whether one’s own or the adversary’s. In Keppley-Mahmood’s view: “In its central philosophical conception of martyrdom, which not only gives meaning to the risking of one’s own life but also to the taking of another’s, militant Sikhism directly challenges rationalistic visions of violent political conflict.”

It certainly does. If even the devout are driven to deeds in which human life means nothing, then it will always be difficult to find rationalistic explanations for their behaviour. In the aftermath of 1984 no attempts have been made in India to analyse the sense of injustice and outrage that underlay the Sikh militants’ actions, nor the depth of their commitment to early but still live Sikh traditions. From the time Guru Arjan Dev and Guru Tegh Bahadur made the supreme sacrifice for their faith, the concept of martyrdom has been ingrained in the Sikh psyche. If these events transformed a peaceful movement into the most militant witnessed on the subcontinent, they also imbued Sikhs with a purpose-fulness they draw on during times of persecution or repression.

The attack on the Golden Temple complex and the massacre of Sikhs in Delhi were both viewed as religious repression, the avenging of which, far from being seen as a crime, became an article of faith for the militant Sikh; a choice of the individual, not of some distant authority.

“A Sikh later hanged for the murder of an Indian army general said that he imagined the rope around his neck as a lover’s embrace. What sort of a world-view does a comment like that spring from?” A world-view is obviously of less importance to a militant in his fight for his faith—against a régime he considers tyrannical—than his own beliefs rooted in religious traditions. The Sikh faith, far from teaching mindless killings, emphasizes personal discipline, valour and nobility. But since it also demands the armed defence of Sikh beliefs, excesses are committed in the heat of battle, and boundaries of acceptable behaviour crossed. “The same ‘saints’ who uphold with valour and grace every ideal of the Sikh way of life look the other way when less saintly companions slaughter women and children on buses. These are the contradictions of being human . . .” Possibly for this reason many Sikhs justified the killing of Mrs. Gandhi even though it went against the concepts of valour and nobility enjoined on them by their Gurus.

It was again personal choice that made so many Sikhs join the various groups engaged in the struggle, especially after 1984: the Babbar Khalsa, Khalistan Commando Force, Panthic Committee, All-India Sikh Students Federation, Bhindranwale Tiger Force of Khalistan, Khalistan Liberation Force, Zaffarwal Panthic Committee, and others; each a voluntary grouping, inspired by individual beliefs. Criminals do infiltrate such movements, but most members of these groups appeared convinced of their cause.

New Delhi used disinformation to cloud the issues and to distract public attention from them. Propaganda imaginatively handled is an effective weapon in the hands of unprincipled leaderships, and Indian leaders showed consummate skill in handling it. A part of the disinformation strategy was to project Pakistan as the arch-villain; the abettor, instigator and even motivator of the Sikh struggle. The gullible bought this line. As if Sikhs had never suffered through centuries of wars, bloodshed and destruction in fighting the tyranny of invaders and Islamic rulers. As if Sikh memories—and of Pakistan’s rulers too, for that matter—were so short that the past has receded altogether.

Problems with the Sikhs, it needs reiterating, were created by New Delhi, not Islamabad. Pakistan had nothing to do with the campaign to persuade the state’s non-Sikhs to disown their own language, or the assault on the Golden Temple complex, or the 1984 massacre, or rewarding instigators of these killings with parliamentary tickets and ministerial berths, or stonewalling the attempts to punish them, or refusing to make Chandigarh Punjab’s capital, or taking away Punjab’s territories and river waters.

To assume that state violence has succeeded in weeding out discontent is a myopic view. As Keppley-Mahmood suggests: “It would be too easy to say that if there had been no Operation Blue Star [the Indian army’s assault on the Golden Temple complex], no anti-Sikh massacres, no extrajudicial executions, no custodian rapes, there would be no Khalistan movement. The example of Quebec is right here to haunt us in that regard. But a great deal of the moral justification for insurgency, for many people both inside and outside the movement, wouldn’t be there without this horrific crackdown. And it is clear that the repression of Sikhs makes every aspect of Khalistan activism more vehement and the potential for a kind of reactive fascism more dangerous. This is particularly the case when the panth, the qaum, the nation, is spread across several continents, and has access to education, communication and weapons on a global scale.”

But it should also be remembered that not all Sikhs want Khalistan. The numbers of those who desire it could be surprisingly few. Almost all Sikhs agree, however, that the Indian state will have to adopt more mannerly policies in its dealings with them. They don’t seek special dispensations, but reject discrimination due to their being a “religious minority.” Equally unacceptable is the erosion of laws through repeated amendments of the Constitution, which are whittling away the rights of individuals. The Constitution, unbelievably, has already been amended more than 72 times.

This is how some of the Acts and Amendments have mocked individual freedoms:

The Armed Forces (Punjab and Chandigarh) Special Powers Act, 1983 gives “any commissioned officer, warrant officer, non-commissioned officer” the right in disturbed areas (which is how Punjab and Kashmir were designated by the government) to destroy shelters from where armed attacks are “likely” to be made, and to arrest without warrant a person on suspicion that he is “about” to commit an offence. A person’s house, for instance, could be demolished because it is “likely” to be used for an armed attack against the state!

The Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA), enacted in May 1985, was given even more odious powers in 1987. It poses a grave threat to everyone in India with its provisions for the arresting, indefinitely detaining and even killing of citizens by security forces. Section 21 of this Act puts paid to the internationally recognized concept of justice which holds a person innocent unless found guilty through fair and open trial. According to this Section: “the Designated Court shall presume, unless the contrary is proved, that the accused had committed such offence.”

The 59th Constitutional Amendment operative from 30 March 1981 suspended the fundamental right to life and liberty. This provision was in effect virtually confined to Punjab. (It was, however, repealed from 6 January 1990 by the 63rd Constitutional Amendment.)

In all 30 Punjab-related Acts and Constitutional Amendments— specifically aimed at the Sikhs—were enacted between 1983 and 1989.

These elements of reactive fascism pose a far greater threat to India than many thoughtful Indians realize. If democratic legislation continues to be debased by repressive laws, enforced by a partisan police force, then fascism could come to India. Padam Rosha, former director of the National Police Academy, whose long and distinguished career in the police gives his views a special urgency, articulates his concerns in forthright terms: “The availability of the administration—including the police—to the party in power, for favouring its supporters, harassing its opponents, collecting money and crowds and doing whatever is dictated by the interests of the ruling junta, is now taken for granted. The police is more than willing to use this partnership for its own aggrandizement, enrichment and eventually as an insurance.” Rosha rightly adds that “the seeds of fascism lie in projecting overly-ambitious and unscrupulous police officers as role models.”