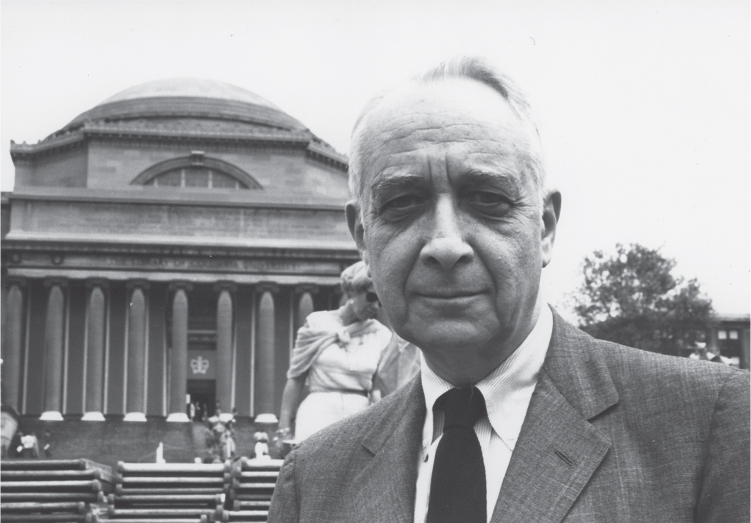

Lionel Trilling in the 1960s in his office in Philosophy Hall at Columbia University, where he taught for more than thirty years.

Courtesy: University Archives, Columbia University, in the City of New York

Lionel Trilling in the 1960s in his office in Philosophy Hall at Columbia University, where he taught for more than thirty years.

Courtesy: University Archives, Columbia University, in the City of New York

LIONEL TRILLING, STALINIST FELLOW TRAVELER?

THE SPY WHO NEVER WAS

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) never conducted a formal investigation of Lionel Trilling.1 But the FBI dossier on Trilling discloses that the Bureau followed his activities intermittently for almost three decades, periodically searching his records, interviewing him to uncover information about his acquaintances, and investigating him as a possible security risk long after he had resigned from the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners (NCDPP), a Communist Party (CP) affiliate organization consisting largely of writers and intellectuals.2 The FBI files comprise sixty pages exclusively about him and include more than two hundred pages involving other investigations in which his name arose, prompting agents to monitor him.3 The dossier runs from 1937 to 1965 and covers reports from regional FBI offices in New York City, Boston, Detroit, and Baltimore, though numerous pages are blacked out or redacted; most concern the Alger Hiss–Whittaker Chambers case.

Most of these reports address Trilling’s peripheral connection to ongoing FBI probes and to its scrutiny of communist figures and issues, ranging from Leon Trotsky and his connections to sectarian American Trotskyist groups in the 1930s to the Soviet Union’s anti-Semitism and the U.S. embargo against Castro’s Cuba in the 1950s and 1960s. Much of the file addresses Trilling’s novel, The Middle of the Journey (1947), because one of its protagonists, ex-CP member Gifford Maxim, was closely based on Whittaker Chambers, whom Trilling knew personally from their student days together at Columbia in the early 1920s.4 The file lays bare the inadequate modus operandi of certain FBI practices, exposing the bulky and ill-fitting nature of off-the-rack uniform routines in the standard data collection methods of secret intelligence agencies—especially when it comes to that top-heavy, asymmetrical creature, the intellectual. Defying basic common sense, no agent ever seems to have read any of Trilling’s work to ascertain his political positions, except for what one agent refers to as the Bureau’s “review” of Trilling’s novel to determine whether it contained any useful information on Chambers’s communist past. The agent determined that it did not. Chambers had tried to recruit both Trilling and his wife, Diana, for Soviet espionage. In her 1993 memoir, The Beginning of the Journey: The Marriage of Diana and Lionel Trilling, she candidly reports that she was proud to be asked, and although she refused, she felt sufficiently beholden to Chambers and the revolutionary cause that she never phoned the FBI.5

Diana Trilling in her fifties.

Courtesy: University Archives,

Columbia University

The Bureau never seriously harassed Lionel Trilling. Nonetheless, his dossier constitutes important historical material. Among other things, as I mentioned in the Introduction, his file makes clear that the FBI’s intermittent attention to him was not only misplaced but also represented a poor use of government resources.

What role, if any, did Trilling’s Jewishness play in arousing the FBI’s interest in him? It is hard to say. Numerous other intellectuals coming of age in the 1930s and 1940s possessed similar immigrant backgrounds, including several other members of the Partisan Review group of Jewish intellectuals in New York City. FBI investigations of other Jewish intellectuals in New York make it likely that his Jewishness played some role, especially given that Trilling had served as assistant editor of Menorah Journal in the 1920s and 1930s. The FBI probably compiled a dossier on Trilling because he briefly joined a Communist front organization during the mid-1930s and was an acquaintance during his college years at Columbia of fellow classmate Whittaker Chambers.

A FELLOW TRAVELER’S JOURNEY ABANDONED

An active file was maintained on Trilling from the late 1930s to the mid-1960s. The file was updated when his name became connected with FBI security checks, such as the Chambers-Hiss investigation of the late 1940s, or with the invitation list to the White House Festival of the Arts sponsored by the Johnson administration in the mid-1960s. Five organizations and/or events that triggered FBI investigations during these three decades cover most of Trilling’s dossier: the Trotsky Committee in 1937–38, the Revolutionary Workers League in 1944, the Hiss-Chambers saga during 1949–50, the Authors League of America in 1950–51, and the Festival of the Arts in 1965.

One might have expected Trilling’s FBI dossier to have begun in 1932 or 1933, when he was a member of the NCDPP and an active fellow traveler whose allegiance was to revolutionary Marxism.6 Trilling was a CP sympathizer long before his involvement with this communist-front organization; Mark Krupnick estimates that Trilling’s embrace of revolutionary Marxist doctrine and radical activism “lasted about four years,” ending at the time of the Moscow show trials in 1936–37.7 If so, that would mean that FBI surveillance of him commenced just as his formal adherence to Marxism was concluding (though he apparently remained sympathetic to Marxism for a while longer).8 After this time, however, Trilling did join the nonpartisan Labor Defense, an independent radical group of anti-Stalinists. Trilling’s literary activities during these years included politically aware book reviews (for example, for the Nation and New Republic); a socially sensitive Great Depression prose fiction work quite skeptical toward American bourgeois capitalist values (never completed and published in 2008 as The Journey Abandoned); and a dissertation on Matthew Arnold as man of letters and representative Victorian (published to acclaim in 1939).9

The FBI apparently opened a file on Trilling in February 1937 because he aroused the attention of the Bureau’s New York office, which had launched an investigation of the members of the so-called Trotsky Committee, formally known as the American Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky, which sponsored an inquiry into the charges against Trotsky during the Moscow Trials. The committee consisted of nationally prominent liberals and radicals, including John Dewey, Norman Thomas, Max Eastman, Suzanne La Follette, and James Farrell. Other members belonged to Trilling’s immediate circle around Partisan Review—Meyer Schapiro, Edmund Wilson, Mary McCarthy, James Rorty, and Sidney Hook. The acting secretary was a good friend of Trilling’s and a lifelong Trotskyist functionary and ideologist, George Novack.10 Trilling’s FBI file includes several letters from Novack to him and to the other Trotsky Committee members, and the FBI memos bear numerous underlinings and notations next to the names of Trotsky Committee members listed on the official committee letterhead.

Trilling may have supported the committee’s activities financially as well as intellectually. A June 22, 1937, letter from Novack reported on the Mexican hearings conducted by John Dewey, which Harper and Brothers had agreed to publish “provided the Committee purchase 2,000 copies in advance. We must act immediately, and to do so must have your aid.” Trilling was asked to contribute to the fund established to publish the hearings. Unfortunately, the FBI file does not disclose Trilling’s personal response to these requests from the committee, nor does it record whether he contributed much more than his name and reputation to its activities. A second memo, issued on October 18, 1944, by the Bureau’s Chicago office reopened Trilling’s file and addressed his loose affiliation with the runaway Trotskyist faction of the Workers Party, the Revolutionary Workers League (RWL), which split away in 1935 in opposition to the party’s Popular Front policy.11

One special agent attended an RWL meeting in Chicago on October 9, 1943. His report, along with reports of other agents (on meetings of May 12 and August 1, 1944, in Cleveland and on September 6, 1944, in Chicago), were sent directly to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s office. One meeting is described as follows: “The evening was devoted to a discussion of theoretical Marxism and some time was devoted to the drafting of a resolution with reference to the No Strike Pledge which apparently was to be introduced at the coming United Automobile Workers Convention in Grand Rapids, Michigan.” The memo—which focused on Sid Okun, acting national secretary of the RWL—also included the names of the members and contacts of the RWL in various states. Trilling’s address appears on this list of names to support activities defending a Michigan African American who was tried and executed for the murder of his white landlord. A lengthy FBI report dated October 8, 1944, and titled “Revolutionary Worker’s League,” includes references to Trilling. According to a memo of July 31, 1950, summaries of RWL activities based on articles from newspapers and magazines such as Compass were later added to Trilling’s file.

THE CHAMBERS CONNECTION

The most substantial section of Trilling’s FBI file, however, deals with his connection to Whittaker Chambers. This third section of Trilling’s file begins in March 1949. On March 9, an FBI agent in New York sent Hoover’s office a copy of The Middle of the Journey, along with a summary of an article that had appeared in the February 13 New York Herald Tribune. The summary discussed the parallels between Trilling’s novel and the developing perjury case against Hiss that featured Chambers as the chief accuser for the prosecution.12 The article by Bert Andrews was headlined “Novel Written in 1947 Parallels Much of the Hiss-Chambers Story.”13

A special assistant to the attorney general, Thomas J. Donegan, read this article and asked for a copy of the novel to determine whether its information “could possibly be of use to Hiss and his attorneys.” The FBI agent noted that “there was some question as to whether the book or the author would figure in the trial of Alger Hiss.”14 As Trilling recalled in his introduction to the 1975 edition of The Middle of the Journey, he had refused in 1949 to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee to testify about Chambers, characterizing him as a “man of honor.”15 However, the agent concluded, “This book has been reviewed and it is not believed that any information contained in this book is of any value in this investigation, although there is some similarity to Chambers’ activities after he had broken from the Communist Party in 1938. This was explained by Mr. Trilling in his statements [during a 1949 FBI interview] that he had known Chambers and that portions of his book were written on the basis of his knowledge of Chambers’ background.”16 Two agents had interviewed Trilling in 1949 about the novel, but his file contains no details about the interview.

The New York office then sent a full-length report, compiled by Special Agent Thomas G. Spencer and dated May 11, 1949, to Hoover. The memoranda included extensive written statements submitted by Chambers. The purpose of the report was to show “the connection between certain unknown subjects and activities mentioned by Chambers, and those mentioned by other informants. … A review of the information … has indicated beyond any doubt that they were members of the same Soviet espionage group.” Copies of this memorandum were also submitted to a number of FBI regional bureaus, including the offices in Boston, Baltimore, Denver, Los Angeles, New Haven, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Washington, D.C.

Later, under the section “Leads,” Spencer, a New York agent, promises to interview Trilling again for information regarding Chambers. Spencer did so on October 12, 1950, at which time Trilling reported that he and Chambers had never visited in each other’s homes; nevertheless, Trilling said, he “feels that he is very well acquainted with Chambers.” Trilling described Chambers as “possessing a strong sense of social decency” and that he had an “extremely gentle, kind manner.” But Trilling knew “very little” concerning other members of Chambers’s circle.

Most of the material in this section of Trilling’s file does not pertain directly to him or to The Middle of the Journey. The comprehensive May 1949 FBI report chiefly covers Chambers’s activities from 1934 to 1938, when he was a member of the Communist Party and the CP underground. Several agents from the New York and Baltimore offices compiled Chambers’s “Personal History” based on interviews with Chambers by special agents J. J. Ward, F. X. Plant, and Thomas G. Spencer. It begins in classical fashion: “I was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on 1 April 1901 as J. Vivian Chambers.”17 Several pages then follow about Chambers’s childhood and rearing. The level of detail extends to mentioning that “the attending physician [at Chambers’ birth] was a Dr. Dunning.”

FBI agents carefully indexed Chambers’s statement. The section dealing with his college years at Columbia, when he served as editor of Columbia Magazine, includes scattered mentions of Trilling’s name with the surrounding contents blacked out.18 Also appearing in the Chambers section of Trilling’s file is a summary of a hostile November 24, 1947, Daily Worker review of The Middle of the Journey by Ben Levine. Another review, written by Frank C. Hanighen and dated April 4, 1949, is also included in Trilling’s file and had appeared in Not Merely Gossip, a supplement to Human Events, a right-wing magazine that soon became a supporter of Joseph McCarthy.

That article, “Spies,” says that within intellectual circles, there was “a revived interest in a half-forgotten volume reputed to contain the answer to a key problem to the current espionage cause célèbre. The book is The Middle of the Journey, a novel by the distinguished literary critic Lionel Trilling and it was published in 1947, a year and a half before Mr. Chambers made his appearance on the public proscenium.”19 The agent adds, “If the author did not know something about at least one of the now widely publicized persons, he must have had clairvoyant imagination.” The Hanighen review also cites a few parallels between Trilling’s novel and Chambers’s character and history.

This FBI document is from the section of Trilling’s file that pertains to his relationship with Whittaker Chambers. Despite the tenuous connection between the two—Trilling had partly based one of his characters in The Middle of the Journey (1947) on Chambers—dozens of pages about Chambers appear in Trilling’s dossier.

THE AUTHORS LEAGUE OF (UN)AMERICA?

A fourth and related issue that renewed the FBI’s interest in Trilling involved the Authors League of America, on whose board Trilling also served. Founded in 1912, the Authors League represents the interests of authors and playwrights regarding copyright, freedom of expression, taxation, and other issues. Consisting of two component organizations, the Dramatists Guild and the Authors Guild, it is the national society of professional authors and today represents more than sixty-five hundred writers of books, poetry, articles, short stories, and other literary works pertaining both to business and professional matters.

The Authors League came to the attention of the FBI because Chambers, in his capacity as a Time editor, contended in his statement to the FBI that John Hersey, chief of the magazine’s Moscow bureau in the early 1940s, submitted reports for Time that were “obviously and quite openly quite favorable to the Union of [Soviet] Socialist Republics.” (Hersey was vice president of the Authors League under President Oscar Hammerstein; Eric Barnouw served as secretary; among the other officers were Lillian Hellman, Rex Stout, and Lionel Trilling.)

The legal justification for an FBI file to be opened on the Authors League and its members was the new, more vigorous enforcement in 1948 of the Smith Act, which permitted scrutiny for national security reasons of all members of “basic revolutionary groups” in any way connected to “the violent overthrow” of the U.S. government. Formally known as the Alien Registration Act of 1940, the Smith Act made it illegal to teach or advocate the overthrow of the government by force or violence. Adopted in 1940, it was first used against American leftists in 1943, when leaders in the Socialist Workers Party and their supporters in the Minneapolis Teamsters Union were convicted of engaging in seditious activities and sentenced to as much as sixteen months in jail.20

In addition to Chambers’s testimony about Hersey, the Authors League attracted the FBI’s notice because it outspokenly defended its members’ civil liberties. In May 1950, the Authors League declared that the Supreme Court’s refusal to review the case of the Hollywood Ten had perpetuated the situation in which there existed in the United States “a form of censorship dangerous to the rights and economic existence of all authors.”21 An FBI memo advised the Bureau’s agents, “You are instructed to immediately institute a discreet investigation of the Authors League of America to determine whether there is any communist infiltration, influence or control in the League and the extent thereof. In view of the nature of this crime, the investigation must be most discreet.”

But if the FBI’s information gathering about other Authors League members was as slipshod as its investigation of Trilling, the Bureau’s discretion certainly came at the cost of accuracy. For example, a memo from the New York office dated June 9, 1950, notes that Trilling “was listed as an instructor in the Institute for Social Research in 1941. He is also an English professor at Columbia University, and is the author of the novel entitled The Middle of the Journey and a number of book reviews from the New York Times Book Review section.” The reference to the Institute for Social Research—the famous émigré Frankfurt School research group housed at Columbia during the 1930s and 1940s, which had included Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno, among others—is an excellent example of how an obvious error in data collection becomes enshrined in print in a secret file and thus gains the status of biographical fact. Trilling never had anything remotely to do with the Frankfurt School, though he may well have met a few of its members, especially Erich Fromm, who was closely acquainted with Trilling’s intellectual associates around Partisan Review (such as Irving Howe) and who joined Dissent’s editorial board in the mid-1950s.

A memo of December 29, 1950, from the FBI’s New York office closes the section of Trilling’s file covering the Authors League. It underlines the Bureau’s preoccupation with subversive communist organizations as the Red Scare began to build. The memo also notes that the New York membership of the Authors League was estimated at between three thousand and four thousand. “It is an independent organization operating as a labor union. … Information shows some of its members to be affiliated with the CP or communist front organizations, [whose members are] in the minority.”

NO SECOND VISIT TO CAMELOT

Several regional offices intermittently followed Trilling’s activities from the late 1950s to the mid-1960s. But he was no longer considered relevant to any pressing public issue of national security after the Red Scare and McCarthyism had subsided in the mid-1950s, and little new information appears in his dossier in this last decade.22

Nonetheless, Trilling’s name also turns up in connection with counterintelligence programs against Fidel Castro and against Soviet anti-Semitic policies.23 In the latter case, a pamphlet, Is Anti-Semitism a Policy of the Present Soviet Government?, was submitted to Hoover, along with a letter to the New York Times cosigned by seven individuals, including members of Trilling’s circle of Partisan Review and Columbia University acquaintances such as Saul Bellow, Leslie Fiedler, Irving Howe, Alfred Kazin, Phillip Rahv, and Robert Penn Warren. The lengthy letter, “Soviet Treatment of Jews,” described Soviet attempts to liquidate Jewish culture during the previous decade. It also asked that Soviet Jews be given the freedom to immigrate, noting that Israel had indicated a readiness to receive them.24

The New York office investigated Trilling between December 9, 1958, and January 22, 1959, and inquired into conversations between Trilling and the New York District Attorney’s Office. The Trillings were carefully tracked during that six-week period. According to one confidential memo, on December 23, “Agents of the New York office observed the subject leave his residence at 8:20 a.m. He proceeded via taxi to Grand Central Station where they boarded a train at Track 37, scheduled to leave for Detroit, Michigan, 9 am.” Indeed, the report reads as if Trilling were being tailed, though the justification for such security—let alone the waste of U.S. taxpayers’ money—is never made explicit in the file. We are merely informed that such measures are evidently preliminary to an updated security clearance for Trilling.25

The final major item in the Trilling dossier is another FBI security check, conducted at the request of the White House when Trilling was screened for a possible invitation from President Lyndon Johnson to attend the gala cultural event of his presidency, the White House Festival of the Arts. Unlike Dwight Macdonald, who later published a report of his visit, Trilling ultimately was not invited to Johnson’s festival. One factor that may have played a role in Trilling’s exclusion was that he and Diana were guests at the Kennedy White House in 1962 and received lavish praise from the president: Diana Trilling later recalled in her memoir, “A Visit to Camelot,” that Kennedy had even exhibited an awareness of her husband’s literary-critical studies, such as The Liberal Imagination.26 Johnson harbored an intense dislike for Camelot admirers and an even greater aversion to those whom JFK admired.

The Johnson festival was scheduled for June 14, 1965, just as U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War was escalating dramatically. Prominent writers and intellectuals in Trilling’s circle were being closely checked by U.S. government intelligence agencies and by the Johnson administration to ascertain whether their attendance would prove embarrassing to the president.27 (Some background checks were obviously slipshod. As we shall see in chapter 3, always a loose cannon, Macdonald circulated a protest petition at the event that garnered fifty signatures, a quarter of guests in attendance.)28

Here again, Trilling’s past connections with radical organizations turn up, and it is unclear whether they proved a cause for concern. The FBI’s memo dated February 2, 1965, reiterated that its files “reveal that the name Lionel Trilling was carried on the 1937 letterhead for the American Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky.” The Bureau report also noted again that the issue of the Daily Worker dated November 24, 1947, contained a review of The Middle of the Journey that characterized it “as a vicious novel and as being cold, calculated slander of the Communist Party. It was also stated that the book was designed to give the reader one single impression—that the Communist Party in the U.S. is an innocent front for another sinister force.”

Lionel and Diana Trilling were tailed in December 1958 as they departed from their home and “proceeded via taxi to Grand Central Station where they boarded a train at Track 37 scheduled to leave for Detroit, Michigan, at 9 am.” Probably the Trillings were making a Christmas visit during the winter break at Columbia University to friends or colleagues in Detroit. The file contains no explanation of why their movements were tracked; it also is not apparent why this document would need to be so heavily redacted when I received it several decades after the event.

UNWANTED BY THE FBI: TRILLING THE NON-COMMUNIST

Trilling’s FBI dossier contains no bombshell revelations and discloses no technical violations of his civil liberties. But that does not lessen its interest or its representative significance on a number of grounds. First, the total number of pages in Trilling’s dossier shows the thoroughness—or obsessiveness—with which the Bureau cataloged even the most trivial references to a subject. Presumably, files also exist under the names of other members of the American Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky, or other members on the RWL mailing list, or all those names mentioned in connection with the Alger Hiss–Whittaker Chambers case. When one considers that no formal field investigation of Trilling was ever conducted, the frequency with which his name surfaces in FBI records is noteworthy. (The same holds true for Alfred Kazin.)29

Second, a fact most surprising to several scholars at the 2005 Lionel Trilling Centennial Symposium in Louisiana, most of whom were unfamiliar with the research methods of intelligence agencies, was that these extensive FBI files make no reference to any of his numerous nonfiction works, such as Matthew Arnold (1939) or The Liberal Imagination, which received glowing reviews across America in 1950–51, or to any of the quasi-political articles that he wrote for pro-Stalinist publications of the 1930s such as the Nation and the New Republic.

As I had discovered decades earlier in my examination of several intelligence agency dossiers of George Orwell, G-men are not readers. They are listeners and sometimes interviewers. But they do not bother much with the kinds of literary research that most scholars conduct. The only title that agents ever even cite in Trilling’s file is his novel, The Middle of the Journey, obviously because of its relevance to the Hiss-Chambers case. (Trilling’s application of his knowledge about communism toward literary ends also did not arouse any interest from the FBI.)30 Oddly, the file does not allude at any point to the NCDDP, the Communist-front organization that he joined (though it is conceivable that references are made to it in some of the pages blacked out in the dossier). Rather, the file indicates that FBI agents are not inclined to read and instead simply rely on newspaper accounts and the tips of informants. Indeed the Bureau’s entire investigative approach to Trilling and his literary acquaintances stands as an ironic commentary on Nathan Zuckerman’s line in Philip Roth’s The Prague Orgy: “The police are like literary critics—of what little they see, they get most wrong anyway.”31 Amusingly, as Trilling’s FBI dossier shows, in America—despite assembling comparable mountains of surveillance data—the “intelligence” agents are the nonliterary critics (i.e., they cannot be bothered to read texts).

Third, several Trilling scholars at the symposium in 2005 were surprised to learn that the Bureau investigated Trilling extensively even though he had become—as their own report on The Middle of the Journey recognized—a firm anti-Stalinist. But the FBI was not very keen on distinctions within left-wing circles. Agents could not understand splits between Trotskyists and Stalinists and were suspicious, always looking for conspiracies.

This fact brings to mind a hilarious (perhaps apocryphal?) story that Alfred Kazin told me. He said that it circulated widely about the intelligence-gathering agencies as well as the local police in the mid-1930s. A memorial was being held in 1934 in New York’s old Madison Square Garden to honor the Austrian Socialists who had risen up against Dollfuss’s fascist regime and were slaughtered with Mussolini’s assistance. The memorial was broken up by Communist Party supporters loyal to Stalin who began throwing chairs down on participants from the upper balconies. People ran screaming out of the Garden, and a minor riot broke out between the two rival groups, attracting a number of curious onlookers. Within moments, the police and some G-men were on the scene, dragging people away and banging a few heads. One man being hauled off was heard to protest to a burly New York cop, “But Officer, I’m an anti-communist!!” The gruff reply came with a firm tug: “Look! I don’t care what kind of communist you are! You’re coming down to the station!”32

All this also points to a larger irony.33 During the period when he was under FBI surveillance in the early post-war era, Trilling became quite approving of American political and cultural life as reflected in Partisan Review’s famous 1952 symposium, “Our Country and Our Culture,” when he applauded “the great American tradition of non-conformism,” lauding the “American way of life” for its “pluralism” and “diversity.”34 Irving Howe, Delmore Schwartz, and Joseph Frank criticized Trilling during the 1950s for his allegedly uncritical celebration of American culture and his “complacency” and “accommodations” toward U.S. shortcomings.35 In light of his FBI file, their criticisms possess greater force than Trilling’s conservative admirers have allowed.

But the additional irony points back to the Bureau itself, which, as Kazin’s anecdote shows, remained utterly incapable of understanding American intellectual culture and its relationship to public life. The FBI never seems to have figured out which American intellectuals presented security risks, as is evidenced by the contrasting treatments of Trilling and Macdonald. It was common knowledge in New York that Macdonald was always a mercurial spirit and more willing than Trilling to take chances (the 1965 Festival of the Arts petition, the 1968 Columbia student strike, and so forth). Yet Macdonald was given a pass by the Bureau and thus permitted to embarrass Johnson at the Festival of the Arts. (Critics of the Bush administration’s Patriot Act would maintain that intellectuals’ experience at the hands of the American “intelligence” agencies is no different today.)

Fourth, Trilling’s FBI dossier possesses representative significance as an illustration of the kinds of subjects that occupied intellectuals of the 1930s and 1940s and of the types of organizations and activities of intellectuals that American intelligence-gathering agencies investigated during those decades. Trilling himself was certainly no security threat. Yet because of his youthful affiliation with a communist organization and his personal acquaintance with Chambers—and particularly because Chambers featured as a central protagonist in The Middle of the Journey—Trilling drew the attention of the FBI and other intelligence organizations. The timing of The Middle of the Journey’s publication in 1947, just months before the Hiss-Chambers case exploded in the press, probably played a decisive role in renewing the FBI’s interest in Trilling.36 The novel obviously resulted in an enormous expansion of his FBI dossier. If it were not for his early communist flirtation and later his treatment of Chambers in his novel, it is highly unlikely that the FBI would have paid any sustained attention to him at all. Far more than most other members of the Partisan Review group—above all, far more than either Macdonald or Howe—Trilling’s active involvement with communism was minimal and lay roughly fifteen years in his past by the time of the Hiss-Chambers case. Still, given the ignorance of intelligence agents about the history of American radicalism and the activities of many American intellectuals, Trilling’s onetime affiliation with a communist-front organization forever marked him as a potential risk in the eyes of some FBI agents. That is to say, as is indicated by the renewal in the 1950s of the FBI’s pre-war interest in the activities of radical American intellectuals, “You can never outrun your history.” Or, as the Kazin anecdote suggests, “Once a communist, always a communist.”

If so, then the past is never truly passed. From this point of view, as I mention in the Introduction, Trilling’s FBI dossier traces the shadow life, as it were, of Trilling’s progressive (or “subversive”) connections with communism beyond his formal association with Communists and their activities in the early 1930s. The dossier may therefore also be viewed as a penumbra of his past, demonstrating how the past lives on into the present—and in fact the files do furnish a shadowy reflection of his ongoing, if limited and tangential, connections to various students, colleagues, and acquaintances still affiliated with communist groups and activities long after Trilling had dissociated himself formally from any such organizational relationship.37

Lionel Trilling in his sixties in front of Columbia University’s Butler Library.

Courtesy: University Archives, Columbia University

Trilling, like many others of his generation, was on the fringe of various left-wing movements, a position that brought him into contact with the FBI. He had a minor involvement with the Trotsky Committee but very little contact thereafter with communist circles. (One scholar has recently examined Trilling’s activities and writings in close detail during the early 1930s and has characterized this period of Trilling’s life, “Trilling the Communist.”38 But Trilling’s FBI dossier suggests that his entire career after the age of thirty should instead properly be characterized as “Trilling the Non-Communist.”) Indeed Trilling’s FBI file also shows that he posed no security risk to Columbia University. That is doubtless why he was cleared in 1953, as McCarthyism and the so-called witch hunts in the American academy were still on the rise, to head the university’s faculty committee that evaluated professors and staff members for national loyalty.

All this prompts another question: How might Trilling have reacted if he had obtained his FBI file and discovered that the Bureau had snooped on him? I doubt the Keystone Cops investigation into Trilling’s life would have drastically changed his political views during the 1950s (or later) if he had known about it. I doubt that his pro-Americanism would have been much shaken. Trilling’s parents were very pro-American (much more than were the parents of the other leading PR writers). Even in the mid-1930s, Trilling was not disgusted with America,39 and his early post-war support for America had to do with weighty geopolitical matters: America as the wartime foe of Nazi Germany, America as the Cold War bulwark against the Soviet Union, America as the Western showcase of cultural and intellectual creativity. Trilling’s sympathy with the “American Way of Life” had also to do with something more archaic as well—he believed that support for one’s country was not a function of circumstance but rather a matter of honor, something that was almost Victorian in Trilling (and that he perceived in Orwell, for example). Trilling would have found his own FBI file silly and slightly sinister, but he likely would have dismissed it as a bizarre side effect of the Hiss case.40

So Trilling’s treatment by the Bureau is not a case study in political repression. He certainly was no victim of McCarthyism—unlike the cases of the blacklisted Hollywood radicals and numerous famous literary figures on the Left.41 During the 1968 Columbia riots, student radicals may have decried his anti-communism and put up posters bearing his picture with the inscription “Wanted, Dead or Alive, for Crimes against Humanity,” but the G-men didn’t really want him. They were never truly preoccupied with him—only with some of his acquaintances.

Nonetheless, the Trilling files offer a salutary lesson. Americans today must expect—and speak out against—even “mild” infringements on our civil liberties such as this one. Trilling was a leading American professor by the mid-1940s and had not been affiliated with any left-wing political organization for more than a decade; he was favored in the 1950s with government-sponsored and -financed junkets to Europe, courtesy of Perspectives USA, a CIA-front publication that fell loosely under the umbrella of the Congress for Cultural Freedom (whose CIA connection was not publicly exposed until the mid-1960s.42 If anyone was politically safe as a U.S. government security risk by the mid-century, it was Lionel Trilling. At best, Trilling’s surveillance by the FBI was wasteful and misguided. Our public servants owe the American citizenry both wiser decisions about the allocation of government resources and greater respect for our personal freedoms.