Irving Howe in his office at Stanford University, 1962.

Courtesy: Nina Howe

IRVING HORENSTEIN, #7384A AKA “REVOLUTIONARY CONSPIRATOR” IRVING HOWE

TAILING A “TROTSKYITE”

The file on Irving Howe (né Horenstein) compiled by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) discloses that its agents followed his activities closely for more than eight years. It searched his records extensively, interviewed neighbors and colleagues to uncover information about his activities, and pursued him as a national security risk long after he had resigned from the Independent Socialist League (ISL), a tiny, New York–based Trotskyist sect.1 The file contains 148 pages, 15 of them partially or wholly blacked out. It runs from February 27, 1951, to April 14, 1959, and covers reports from regional FBI bureaus in New York City, Albany, Newark, St. Louis, Miami, Boston, and Detroit.2

Most of these reports address Howe’s activities in the ISL and his membership in Trotskyist organizations in the 1940s and 1950s. Much of the file covers Howe’s statements in public lectures about the Soviet Union and regarding the changing nature of Stalinism during the 1950s. One glaring feature of the file is conspicuous by its absence, though it is perhaps by now unsurprising. As with Lionel Trilling and Dwight Macdonald, the fact that no agent ever seems to have read any of Howe’s work to ascertain his political positions speaks volumes about the one-size-fits-all information-gathering procedures of the American intelligence services during the Cold War. The sole exception is the joint resignation letter that he and Stanley Plastrik submitted to the ISL in 1952, a copy of which was obtained by a Bureau informant.

For historians and scholars, one irony in Howe’s dossier that he would doubtless have appreciated is that FBI agents (however unaware of the irony) repeatedly call him, using the same invidious language as did his Cold War–era Stalinist opponents, a Trotskyite, a term that also occasionally surfaces (along with Trotzkyite) in Macdonald’s dossier. The Feds used the labels Trotskyist and Trotskyite interchangeably. Communist Party sympathizers knew better. They wielded the latter characterization as a cudgel. But the G-men failed to recognize any distinction between the two words.

The highlight of the FBI file on Howe (a name that the Bureau persisted in treating as his “alias” although Howe had legally changed it in 1948) is the hour-long interview that two agents sprung on him in August 1954.3 When they approached him as he entered his car on a street in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the agents were impressed by his “friendly and cordial manner,” though they later urged that a Security Index file be opened on him for long-term surveillance. Although Howe was never again confronted directly, the FBI kept watch on him for five more years. Reports continued to be placed in his file on his lectures to university audiences and to political clubs and even on his “luggage lost in France” during a trip to Europe in 1957.4

Howe’s FBI file also furnishes a valuable biographical background for his repeated castigation of McCarthyism in the 1950s: it shows that Howe himself was being “tailed.” After his semipublic “street interview” with the two FBI agents, if not long before, he certainly suspected as much. Such information puts in context his radical critique of U.S. policies and at the same time undermines part of the ad hominem neoconservative attack on his writings during the McCarthy period. Many of Howe’s critics have argued that his 1954 essay, “This Age of Conformity,” reflected his hypersensitivity regarding First Amendment freedoms. These critics imply that Howe harbored excessive and even irrational fears about government infringement on American civil liberties and about encroachments on personal privacy. His first biographer, Edward Alexander, refers to Howe’s “compulsive … indictment of liberals who fail to take seriously the threat to civil liberties.”5

Yet Howe’s FBI file makes clear that in his case, this supposed compulsiveness actually constituted appropriate vigilance.6 The criticism that he and PR writers such as Alfred Kazin expressed about the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) and the Smith Act (formally known as the Alien Registration Act) in the 1950s still holds up six decades later.7 The organizations classified as “revolutionary” under the Smith Act included a pair of Trotskyist groups to which Howe belonged, the SWP and ISL.

In fact, as I mentioned in chapter 1, Howe’s lectures were secretly visited by Bureau agents or informants, his mail was intercepted and opened, and his daily activities were regularly reported and updated (residential addresses, phone number, magazine subscriptions). This eavesdropping continued for almost seven years after his formal resignation from the ISL. In addition, Howe’s second wife, Thalia Phillies Howe, was subject to investigation during her years as a teacher at Miss Fine’s Day School in Princeton.

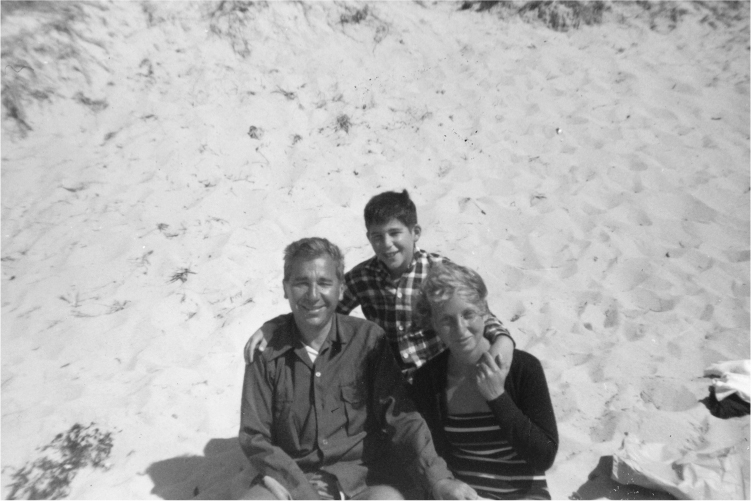

Alfred Kazin at Cape Cod with son, Michael, and (second) wife, Ann Birstein, in the mid-1950s, around the time when he began to support campaigns on the left to abolish the House Un-American Activities Committee.

Courtesy: Michael Kazin

Although he was apparently unaware during the 1950s and 1960s that the FBI was engaged in such wide-ranging surveillance of his and his family’s private life, Howe would likely not have been surprised. According to the FBI reports of that afternoon in August 1954 when the two special agents suddenly stopped him on the street, he was quite “affable,” “friendly,” and “cordial” throughout the session.

Still, Howe’s intellectual integrity forbade him from equating these invasions of his privacy (and indeed infringements on his and his family’s civil liberties) with conditions in the USSR or in Soviet-occupied Eastern Europe either before or after Stalin’s death in March 1953. Howe and Dissent, which he cofounded with Stanley Plastrik in January 1954—and whose launch may have prompted the FBI interview a few months later—not only fearlessly and relentlessly castigated McCarthy and his supporters but also inveighed against the U.S. government’s abuse of the Smith Act, as Howe also did so directly to the two FBI agents who interviewed him.

Both Howe and Dissent subscribed to a “moderate” radicalism. At no time was Irving Howe a breast-beating, shrill critic of American domestic life, let alone an incendiary, flame-throwing radical extremist—in fact, his frustration with such compulsions on the Left, especially as voiced against the New Left from the mid-1960s on, led to his vilification by the leaders of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and by influential counterculture figures. His derision for the New Left never ingratiated him with the political mainstream or with conservatives.8

While Howe and Dissent deplored the domestic conduct of the FBI and some other government agencies, it was far from his intention to compare their cavalier treatment of American civil liberties with the arbitrary lawlessness of Communist police states. Like Dwight Macdonald, for whom Howe had worked as an assistant at politics in the 1940s (even serving briefly on the editorial board), the Irving Howe of the Dissent years was “a Critical American” in the sense of opposing any political position that rubber-stamped American domestic security policies or insisted that civic duty entailed uncritical celebration of the “American Way of Life.” Howe never felt that his career was imperiled as a result of his public derision of McCarthyism, and he insisted on distinguishing the relatively mild abuses of U.S. government intelligence agencies from the despotic practices of the Soviet security forces. Nor did Howe ever equate the injustices suffered by some American radicals with how Soviet and East European intellectuals might be subject willy-nilly to house arrest or forced incarceration in psychiatric hospitals.9

So Howe would not have viewed himself as a hapless victim of political repression. He was well aware that other American intellectuals, artists, and entertainers—to cite just those in the world of American culture—were subject to far worse treatment than was he. Some of them lost their jobs as university professors or schoolteachers, others were blacklisted (e.g., as Hollywood screenwriters), and still others were harassed and summoned before HUAC to testify against former colleagues and friends (and in some cases were forbidden to travel or jailed on contempt charges for invoking the Fifth Amendment). By contrast, the periodic monitoring of Howe and his family represented an annoying pinprick, as he would have acknowledged. Although Howe’s FBI file is far larger than that of either Trilling or Macdonald and the surveillance is clearly more intrusive and enduring, Howe’s treatment by the FBI, even during the worst period under McCarthyism, produced no lasting or significant negative results for his personal or professional life. Instead, his career during the 1950s and 1960s advanced in a constant upward trajectory: his essays found their way into America’s prominent mainstream magazines, his books appeared from the best publishing houses, his lack of a PhD proved no obstacle to professorships at prestigious universities (including Brandeis and Stanford), and Dissent’s circulation rose as its visibility widened.

As with Trilling and Macdonald, the FBI’s pursuit of Howe is exemplary because of its needlessness, wastefulness, and maltreatment of an innocent American citizen who was simply voicing “dissent.” Howe was doing so via platforms ranging from distinguished magazines such as Partisan Review and well-known New York publishing houses and was therefore attracting more notice and exerting more influence than most citizens. In principle, however, his activity was no different from theirs. The main difference was that his opinions were delivered in print from publications that were being discussed by interested and informed citizens throughout the nation.

LIFE OUTSIDE A SECT

The Bureau maintained an active file on Howe during 1951–59, including a Security Index on him in the Boston division. Howe’s ethnic background may have been a factor—the Bureau pointedly noted that “his father, David [Horenstein], was born in Russia and was naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1922, according to the records furnished by CCNY” (the City College of New York). The Russian birth might have indicated to the FBI a possible sympathy with communism.10 But the specific occasion for the FBI file on Howe was the more aggressive use of the Smith Act in 1948–49 to prosecute radicals, which resulted in the conviction of several leading members of the American Communist Party (CPUSA) in October 1949. Passed in 1940, the Smith Act justified the scrutiny for national security reasons of all members of “basic revolutionary groups” committed to “the violent overthrow” of the U.S. government.

With the official support of the CPUSA, the Smith Act had first been used against the Left in 1941 to convict and jail SWP members, including its leader, James P. Cannon. In a letter to the Loyalty Review Board (September 29, 1949) contained in Howe’s file, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath described the ISL as a “basic revolutionary group,” the successor to the revolutionary Workers Party. Howe had belonged to the Workers Party since 1940 (and was a member of its national steering committee in 1946), and he had served as editor of the weekly Labor Action, the official organ of both the Workers Party and the ISL. (McGrath’s letter specifically cited Labor Action.)11

Despite several background checks on Howe’s agitprop activities in the 1940s, the FBI remained unaware that not long after entering the army, Howe resurfaced in both Labor Action and New International under the pseudonym R. Fahan, writing anti-war polemics. Especially after Trotsky’s assassination in 1940, most American Trotskyists, including the Schachtmanites, took a strong position against the Second World War, condemning it as a battle among capitalist-imperialist powers, including the “state capitalism” of the Stalinist USSR. Howe’s last wartime article appeared in October 1943. He did not return to the pages of Labor Action until February 11, 1946, usually thereafter writing as Irving Howe.12 (The FBI apparently also did not know that Howe wrote under the name Theodore Dryden in 1947–48 for Dwight Macdonald’s radical magazine, politics, or indeed that “subject Horenstein” was not “the father of two boys.”)13

Typical of the FBI’s lack of competence in its intelligence gathering on Howe is its close coverage of the circumstances of his departure from the ISL in October 1952.14 Although the FBI file contains two copies of Howe’s three-page resignation letter, Bureau informants seemed not to know about how complete the rupture was between Howe and the ISL. No mention is made in Howe’s file of the ISL motion prohibiting its members from contributing articles to Dissent unless they received special dispensation. Throughout the 1950s, the FBI treated Howe as if he were still a member of a “basic revolutionary organization.”

Nor was this the Bureau’s only important oversight about Howe’s political activities at this time. The Bureau apparently missed Howe’s public dispute with the ISL two years later—his last contribution to Labor Action. In a scathing attack on the inaugural issue of Dissent, Hal Draper wrote in Labor Action on February 22, 1954, that Howe’s break with the ISL and his founding of Dissent signified that “those who sympathize with his ‘ethos’ must likewise abandon any organized socialist movement, which is to be replaced by such a center for thinkers as his magazine seeks to make itself.”

Howe replied to Draper in the March 15 issue of Labor Action: “I know [your] way of thinking, having suffered from it myself for a good many years.” Howe maintained that Draper and the ISL were living in grandiose denial both about the reality of a socialist “movement” and about their influence beyond the suffocating we of their sectarian circle: “Life in a Sect” was the title Howe chose for the chapter devoted to his Trotskyist days in his memoir, A Margin of Hope (1983). Although some individuals in America could still be called “socialists,” Howe said, “we have no political significance, whatsoever.”15 Nonetheless, the Bureau worried in the early 1950s that socialists such as Howe might build a movement or gain political significance.

“AN IMMATURE OUTLOOK ON LIFE”

Howe’s campus activities in the 1950s at Princeton, Brandeis, the University of Michigan, and elsewhere were also monitored periodically by regional FBI offices. When the FBI began its file on him in February 1951, Howe was living in Princeton, residing in a small house financed by a GI loan. His second wife, Thalia, taught Greek and Latin at Miss Fine’s, a private day school in Princeton.16 A colleague of hers who described herself as “casually acquainted with Irving Howe” provided Newark agents of the Bureau with some information in October 1953 about Howe’s status as a full-time independent writer.

Another informant was Carlos Baker, a distinguished Hemingway scholar who taught at Princeton University. Baker was in the university audience when Howe lectured on the theme of “Politics and the Novel” at the Christian Gauss seminar in the fall of 1952. Baker was forty-three years old and had just published Hemingway: The Writer as Artist. A specialist in British and American literature who had been teaching since 1937 at Princeton, Baker was a rising academic star, soon to be appointed department chair. Baker was also well acquainted with the social milieu of the PR writers, a world Howe had just entered.

According to a September 22, 1952, report from the Newark bureau, Baker told the FBI that he knew “so little about the subject [that] he was in no position to provide any recommendations.” On February 2, 1954, the agent added that Baker “did notice the subject has a very bright mind, a nervous disposition, and an immature outlook on life.”

Although Baker evidently told FBI agents nothing of importance, their conversation with him indicates at minimum that he was willing to provide the Bureau with negative impressions of a young man whose background would certainly have been officially suspect. It also shows that the FBI gained access to prominent scholars familiar with Howe’s intellectual life and reference groups. (Baker’s name evidently appears in Howe’s file because he died in 1987; the names of several other informants or agents, apparently all still alive when FOIA officials last reviewed the dossier, are blacked out.)17

In the fall of 1953, Howe joined the faculty at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachusetts. (He would remain at Brandeis throughout the period of his FBI file; he left for Stanford in 1961.) Within a few weeks, the Boston FBI office was following his activities. One report from the spring of 1954 reported on surveillance of his home in nearby Wellesley: “From January 16 to February 13, 1954, a mail cover was maintained on the residence of the subject at 87 Parker Road. The following are individuals or organizations with whom the subject received correspondence during this period: Dissent, Perspectives, [Stanley] Plastrik, Partisan Review.” On June 2, Boston agents wrote, “Asked New York office to identify and check the references of some 15 correspondents of the subject. Because considerable agent time would be necessary to cover these leads, the New York office will not cover the leads as set out.”

Surveillance of Howe intensified in 1954, perhaps because Brandeis was known as a home for numerous intellectual radicals and Marxists (and ex-Marxists). The timing may also have been triggered by the fact that in January 1954, Howe and his Brandeis colleague, Lewis Coser, joined forces as coeditors on the first issue of Dissent, whose name perfectly captured the stance that they and other contributors to the magazine adopted toward USSR and U.S. government policies, domestic as well as international. Dissent was vehemently anti-Stalinist and anti-Soviet, while a number of editorial board members, like Howe, were former Trotskyists or were refugee radicals with Western European backgrounds, like Coser.

Despite the aggressively anti-Soviet position of the Dissenters—one of the distinguishing features of the group—most FBI agents were not skilled at drawing distinctions about left-wing affiliations among intellectuals. So there was often a tendency, as we have mentioned in previous chapters, to lump together various Trotskyist sects with Stalinist and other Marxist opponents as “Communists.” The Marxist Left included many tiny splinter groups, a number of which were utterly hostile to the American Communist Party and the USSR. But few FBI agents understood the terrain of the balkanized American Left, and for some of their informants (as was the case for Trilling and Macdonald) it was also terra incognita.

Other factors probably also influenced the FBI’s decision to move more aggressively on Howe. For instance, word was obviously spreading in mainstream culture about Howe’s growing stature as an intellectual and activist. (Brandeis president Abram Sachar apparently regarded Howe’s appointment in 1953 as “a major coup,” at least in hindsight.)18 Moreover, Howe was soon to become a well-known campus presence at Brandeis because of his frequent participation in public debates, including face-offs with such figures as Herbert Marcuse, the Stalinist novelist Howard Fast, and Oscar Handlin (who debated Howe on Israel’s capture and planned trial of Adolf Eichmann).

Irving Howe with his son, Nicholas, and daughter, Nina, in 1954, when the family lived in Wellesley, Massachusetts.

Courtesy: Nina Howe

The Boston FBI tracked down “subject Horenstein” for an interview in August 1954, near the Harvard campus.19 The August 26 report of the interview began,

The Boston office interviewed subject Horenstein without prior notice at 2:00 p.m., August 6, 1954 by two Special Agents, on Boylston Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Subject was affable. He stated he would be happy to sit in his own car and discuss ideologies. He continued that this was as far as he would go with the interviewing agents and that he had no intention of identifying or “involving” others in view of what he described as the “misuse” of the Smith Act by the Department of Justice and the use of Executive Order 10450 to “blackball radicals and prevent them from earning a livelihood.” It is to be noted that at no time during the course of the interview was the subject hostile, and throughout the interview he displayed a friendly and cordial manner.

According to the report, “Subject described himself as a ‘Socialist’ and a lifelong ‘anti-Stalinist.’ Subject denied membership at any time in the Socialist Workers Party or any other group or organization which advocates the overthrow of the United States government by force or violence.” Finally, the report concluded, “In view of the subject’s past activities and attitude at the time of interview and his denial of membership in the Socialist Workers Party, it is believed that he should be included in the security index.” The Security Index card was prepared on the same day as the report.

This interview forms the centerpiece of the comprehensive file on Howe compiled by the Boston office on April 8, 1955. That file comprises twenty-six pages, including birth records, educational background, marital status, military service record, employment record, residences, political activities, speeches and writings, and even speeding tickets in Princeton and nearby Cranbury, New Jersey (“ten dollars paid on February 8, 1953, seven dollars paid on 3/23/53”). The April 1955 file also includes Howe’s resignation letter to the ISL, a log of his contributions to the New International between 1946 and 1952, and a summary of three of his fall 1949 public lectures, which reflected the themes of his book, The U.A.W. and Walter Reuther, and coincided with its publication.20

CLOSING THE FILE

Several regional bureaus intermittently followed Howe’s activities during the late 1950s, but he was no longer considered a security risk after mid-1955, and little new information appeared in his file as the decade wound down.

On May 19, 1955, the Boston office decided to cancel the Security Index. However, it sought to justify its expenditure of resources, noting yet again that “the subject registered with the Worker’s Party in June/July, 1946 at which time he indicated he had been a member of the Worker’s Party since 1940.” The four-page report closes, “While the subject has been a member of a basic revolutionary group within the past five years, it is noted that on October 12, 1952, subject directed a letter to the ISL in which he stated he was formally resigning from the ISL, further it is noted that subject has stated that in the event of hostilities with the Soviet Union, the ISL should support the United States. It is, therefore, recommended that he be removed from the Security Index. The security flash note is also to be removed.” This report was filed on June 10, 1955.

Irving Howe (aka Horenstein) was stopped and accosted in August 1954, after he founded Dissent, which billed itself as a “socialist quarterly.” The FBI decided to escalate its surveillance of Howe and make “Horenstein” the subject of a Security Index Card. The FBI “interview was conducted in a particularly circumspect manner,” the report noted, yet this occurred not because the Bureau sought to protect the Howe family’s privacy or Howe’s reputation in the community but instead “in order that no embarrassment to the Bureau would result.”

Nonetheless, the Boston office still conducted occasional spot checks of Howe. His file reports a “pretext telephone call to Brandeis University on 10/30/58, in the guise of an associate attempting to locate subject.”21 Boston agents also tipped off other regional bureaus about Howe’s whereabouts and coordinated surveillance with them. The Detroit file for March 31, 1959, notes that on October 18, 1958, Howe “directed a postcard to Labor Action,” requesting a change of address for his subscription. Indeed, the March Detroit file is a twenty-two-page report, including a substantial nine-page appendix on Howe’s memberships in various socialist organizations.

Howe’s third wife, Arien Hausknecht, taught at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor during part of his leave of absence from Brandeis in 1958–59. The Detroit FBI checked up on him in Ann Arbor and also noted that he was “employed at Wayne State University in the English department on a part-time basis.”22

Detroit agents attended at least three of Howe’s Dissent talks during 1956–58. (Much of Howe’s energy in the late 1950s went into organizing Dissent forums around the country on various political topics, an effort that did not go unnoticed by the FBI.)23 One informant at a Detroit talk reported that the

principal subject of Howe’s talk was how sorry he was to have ever considered himself as a “socialist” and that if he had to do it over again, he would not associate himself with such a movement because he felt that it would never amount to much more than just a movement. Howe further stated that, in spite of its ideals and some of the fanatics [who] are members of various socialists’ [sic] organizations, there is no real socialist movement. Howe, during his talk, referred to Dissent magazine and its program and stated that the magazine staff had considered dropping the word “social” or “socialist” from its program, but had finally decided not to make any change.

This informant was doubtless confusing socialist and Trotskyist, failing to grasp that Howe was referring to his years of membership in the ISL. Even if internal discussions on the Dissent editorial board considered abandoning a formal commitment to “socialism,” Howe proudly and publicly referred to himself as a socialist throughout the 1950s and well after. Howe’s self-professed socialism notwithstanding, however, his overall political outlook had further moderated by the late 1950s, evolving away from a radical politics and toward a firm liberal anti-communism and radical humanism.24 Howe’s anti-Stalinist stance never wavered, but his “socialism” became less an active political engagement and more (as Draper had predicted in 1954) an ethos or axiology, a commitment to what Howe himself in Dissent called “the animating ethic of socialism.”25

To sustain and fortify that commitment, Howe looked for and wrote about European socialists such as Hungarian György Konrád and the Italian Ignazio Silone, both of whom he embraced as inspirational presences. From the mid-1950s onward, Silone was in fact Howe’s most cherished model of radical commitment, the living figure above all others whom Howe exalted as a socialist exemplar for both himself and Dissent readers.26

Like the Detroit FBI, Boston agents were also concerned that Dissent’s public forums might lead to a socialist mass movement.27 (A 1959 forum that featured Erich Fromm, a Dissent editorial board member, drew seven hundred people.)28 For instance, the Boston office reported on “Irving Horenstein” at a Dissent forum on “The Revolt in East Europe” (December 1, 1956) at Adelphi Hall in New York and a forum in Boston (January 30, 1957) attended by a lieutenant of the Massachusetts State Police. According to the report of the New York talk, which dealt with the Soviet invasion of Hungary in October 1956, Howe “definitely was anti-Communist in his analysis and repeatedly criticized the ruthless attacks by the Russian troops.”29

According to an April 4, 1958, report on another Dissent forum covered by the Boston office, Howe “evidenced considerable dejection over the low level of activity that now characterized U.S. socialism.” The file continues, “Howe claims that socialism could meet all the problems that besetted [sic] in our country if trends were to continue unchanged. As he saw them, there would probably result in our country a low-charged autocracy, somewhere between freedom and totalitarianism. Howe stated that in central planning even of the socialist variety, there was a danger that the concentration of powerful planning purposes would destroy freedom and to be successful and accepted, U.S. socialism must be democratic and welcome some degree of small independent business. Howe concluded with a plea for studied regroupment of socialist elements.”

By this time, the FBI had in effect acknowledged that Howe was no “security risk.” But the Bureau’s reclassification was evidently influenced by new legislative constraints, too. The reduced scope permitted to the FBI by judicial decisions following the discrediting of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s witch hunts also limited its pursuit of young ex-Trotskyists like Howe. Indeed, an important reason for the Bureau’s dwindling interest in Howe, along with many other former “revolutionaries,” was that the U.S. Supreme Court had recently defined the Smith Act more narrowly. In 1957, the Supreme Court had ruled on a California case (Yates v. United States), saying that to win a conviction, prosecutors must demonstrate a “clear and present danger.” The Supreme Court thereby sharply curbed the application of the Smith Act, allowing it to pertain only to people who engaged in specific insurrectionist activities or incited others to do so.30 These developments rendered “Horenstein”—a third-rank former “revolutionary” from a negligible sect—of little interest.31

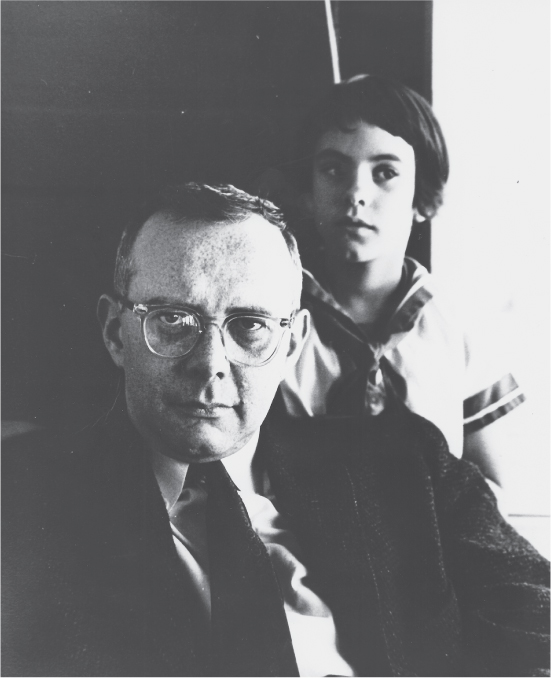

Irving Howe with his daughter, Nina, 1958, when the family resided in Belmont, Massachusetts.

Courtesy: Nina Howe

LESS FREE = MORE SECURE?

Does the treatment of Irving Howe during the McCarthy era hold any lessons for us today? Yes. It serves as a cautionary reminder that we may adopt draconian and obsessive security measures that will comfort all alarmists—but the consequence is that we will become less free, not safer. Less free, not more secure. Such interference with our civil liberties is also an assault on the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

Let us transcend the pseudo-patriotic jingoism that makes us either “100 percent American” or “Un-American.”

Let us question the crude dichotomies common to both the Red Scare and the September 11 decade that make one either with the United States or with the commies and terrorists, respectively.

Let us work together, in a spirit of mutual respect for differences of opinion, to forge a balance between enlightened authority and responsible dissent.