Franklin’s First Full Assembly, the Money Bill, and Susanna Wright, 1751–1752

By rendering the Means of purchasing Land easy to the Poor, the Dominions of the Crown are strengthen’d and extended; the Proprietaries dispose of their Wilderness Territory; and the British Nation secures the Benefit of its Manufactures, and increases the Demand for them: For so long as Land can be easily procur’d for Settlements between the Atlantick and Pacifick Oceans, so long will Labour be dear in America; and while Labour continues dear, we can never rival the Artificers, or interfere with the Trade of our Mother Country.

—Franklin’s “Report of the State of the Currency,” 19 August 1752, 4:350

FRANKLIN AND HUGH ROBERTS were elected Philadelphia representatives on 2 October 1751. The Quaker John Smith recorded that the election was hotly contested and that Franklin received the highest number of votes, 495; that Hugh Roberts received 473; Joseph Fox, 391; and William Plumsted, 303. Smith noted, “A total of 1,662. One half of these being 831, is I suppose a great many more than ever voted for the city before.”1 Of the four, Franklin was apparently regarded as an independent and won votes from members of both parties, though probably not from those absolutely loyal to the Proprietary Party or from the pacifist Quakers. Roberts, Franklin’s good friend, and Fox were both Quakers and members of the Quaker Party. Plumsted, another old friend and a former Quaker, had become an Anglican and a Proprietary Party member.

The assembly of 1751–52 had three sessions: the organizing session, 14–16 October 1751; the second session, 3 February–11 March 1751/2, which met for thirty-three days and did most of the year’s business; and the third and final session, 10–22 August 1752, which met for twelve days. The major business of the year proved to be the assembly’s attempt to pass a paper money bill. In the first session on 14 October, Isaac Norris was unanimously chosen Speaker; and he appointed Franklin to all four standing committees. William Franklin was elected clerk. Then the assembly adjourned to Monday, 3 February.

SECOND SESSION, 3 FEBRUARY–11 MARCH 1751/2

On 3 February 1751/2, Franklin and Evan Morgan performed the formal task of waiting upon the governor and asking if he “hath any Thing to lay before them.” Incidently, the use of hath rather than has probably shows that Clerk William Franklin knew his father’s opinion that the English language had too many “s” sounds and that he often preferred the old-fashioned “hath” to “has” (Life 2:131–32). For the next several days, the House heard various petitions, several requesting the creation of new counties, so that the persons far from the existing county seats could be represented.

From 1751 to 1757, Franklin served on numerous minor committees. I will present Franklin’s minor assignments for the assembly of 1751–52, but subsequent chapters will ignore them.2 On 6 February 1751/2, a petition claimed that most sales held in public places carried goods similar to those in retail shops and that “Strangers, who contributed nothing towards the Support of Government,” imported materials to sell there. After the petition was read for the second time on 7 February, the petitioners were given leave to bring in a bill. They did so on 13 February. On 25 February, it was read the second time and “committed for Amendment to” a committee that included Franklin. But the assembly never returned to it, and therefore, at the end of the third session, 20 August 1752, it was referred, with other bills, to the next assembly. Bills judged of little pressing importance were often put off from one assembly to another. Acts primarily concerned with Philadelphia affairs were usually referred to the Philadelphia Common Council. Neither this bill nor the next was passed during the colonial period.3

Another minor committee addressed the issue of stray dogs. The city and county of Philadelphia petitioned against the nuisance on 12 February. Read for the second time the next day, the petition was referred for further consideration. On 24 February Franklin was appointed to “a Committee to prepare and bring in a Bill.” The bill for licensing dogs was read on 5 March and for the second time on 10 March. When read for the third time that afternoon, the Speaker referred it to the same committee to be “amended against the next Sessions of Assembly.” It, too, dragged on from assembly to assembly before dropping from the record.4

NITTY-GRITTY LEGISLATIVE BUSINESS: FOUR EXAMPLES

The laws specified fees for various official functions, but the schedules had been created when the colony had few inhabitants. By 1752 some fees were exorbitant. On 4 February 1752, the assembly read a petition from York County criticizing the high fees that the officers of the courts, especially the county sheriff, collected. The next day, Cumberland County presented a similar petition, and the following day, 6 February, the third article of a long petition from Chester county also complained of high fees. On 18 February, Speaker Norris appointed Franklin to a “Committee to enquire into the State of the Laws of this Province relating to Fees, and report thereon to the House.” Reporting on 21 February that the fee structure should be changed, the committee was promptly asked to bring in a bill. The Bill of Fees, read on 27 February, specified fees for the Keeper of the Great Seal, the justices of the Supreme Court, the governor’s secretary, the attorney general, the sheriffs of the counties, justices of the peace, justices of the Orphans’ Court, the prothonotary or clerk of the Supreme Court, the clerk of the Court of the General Quarter-Sessions, the prothonotary or clerk of the Common Pleas in every county, the register-general of the province, the attorneys, members of juries and inquests, and so forth. Altogether, the committee specified hundreds of minor legal fees. The bill was read for the second time on 2 March and changes were made. After being considered again on 5 March, it was ordered to be transcribed for a third reading, and on 7 March the bill passed the assembly and was sent to Governor Hamilton, who later replied that he would take “the Bill under Advisement till the next Meeting of the Assembly.”5

At the beginning of the last session of the assembly of 1751–52, the governor’s council read and approved amendments to the officers’ fee bill on 10 August. The House received the amended bill the next day. On 13 August the assembly accepted some amendments and asked Franklin and Mahlon Kirkbride to confer with the governor. The two reported the next day that Governor Hamilton would take the revisions into consideration. He returned the bill on 18 August with amendments. The House agreed to some, “but in others the House adhered to the Bill.” The following day, 19 August, Governor Hamilton replied in writing that the secretary’s duties were so various that it was impossible to set a fee that would “be exactly adequate to each Service”; he also believed that the fees specified for the attorney general were “not equal to the Trouble and Skill necessarily required to carry on criminal Prosecutions.” The assembly voted not to accept the amendments but declared it “would be glad to have a Conference with the Governor.” Franklin attended the 20 August conference. Afterward, the assembly accepted the governor’s amendments and had the bill engrossed. Franklin and Secretary Richard Peters compared the bill on the morning of 22 August, and the governor enacted it later that day.6

In another case, the Germantown overseers of the poor petitioned the Pennsylvania Assembly for reimbursement. In the early winter of 1750–51, five Nanticoke Indians shot and beat an Albany Indian and left him for dead. After the Nanticoke Indians left, however, the Iroquois was still alive. The overseers of the poor asked Chief Justice William Allen what to do. He instructed them to care for the Indian, who gradually recovered. After ten weeks and four days he was well enough to leave. On 7 February 1751/2, after the Germantown overseers requested reimbursement, the House ordered Franklin and Hugh Roberts to “inspect the said Accounts and report thereon.” They replied on 27 February that £12.4.10 should be awarded to the Germantown “Overseers of the Poor,” and that £15 should “be allowed to Doctor Charles Bensel, in full of his Account for Medicines and Attendance in the Cure of the wounded Indian.” The House ordered payment.7

The first act Franklin wrote as an assemblyman that became a law concerned the price of bread. Philadelphia’s bakers petitioned the assembly on 7 February 1751/2 to raise the price of bread because flour was so expensive that they could not make the cheaper breads “without manifest Loss to themselves.” Consequently, poor people could hardly afford bread. The bakers requested that they be able to make smaller sizes of breads, especially of the “brown bread or good ship stuff,” so the poor could afford to buy them. The next day Speaker Norris appointed Franklin to a “Committee to consider the said Petition and the Law of this Province relating to the Assize of Bread, and … prepare and bring in a Bill for the Alteration or Amendment of the same.”8

Perhaps Franklin recalled the cheap “three great Puffy Rolls” he bought when he first entered Philadelphia (A 24), realized how much the price of even the cheapest flour had increased, and reflected that he could not now purchase such a quantity with three pence. The committee agreed that, considering the price of flour, the bakers should be able to charge more. On 21 February the bill was read; five days later it was read again “Paragraph by Paragraph, and ordered to be transcribed for a third Reading.” On 28 February it passed and was sent to the governor. Governor Hamilton proposed an amendment on 4 March. It was agreed to, and the bill was ordered to be engrossed. A week later, it was enacted. The king in council approved it on 10 May 1753.9

A 4 February 1751/2 petition from New Britain, Bucks County, claimed that different creditors applied for different attachments for small debts, “whereby the Defendant’s Effects are consumed in Charges.” It asked for a law to prevent more than one attachment, and for each creditor to receive “a proportional share.” A similar complaint appeared in a petition from Chester County on 6 February. On 11 February, Franklin and others were assigned to consider the “Attachments for Debts under Forty Shillings” and to “report their Opinion what Amendments may be proper to be made in the said Laws.” The committee replied on 14 February that in the case of small debts, legal expenses often consumed “a large part of the debtor’s estate, to the great loss and injury of both debtors and creditors.” The committee suggested that when a suit was brought and sworn to, the magistrate could take the property of the debtor and publish the proceedings. Only one attachment within a county would be permitted. After officials seized the property of a debtor, there must be a three-month waiting period before its sale, giving the debtor a chance to pay. Following the sale, reasonable charges were paid, then the creditors were to share the attachment “in proportion of their respective debts.” The debtor would receive any surplus.10

After being read on 26 and 27 February, the House referred the bill for “further Consideration.” The next day it was read “Paragraph by Paragraph” and transcribed for a third reading. On 29 February, the bill passed and was sent to the governor, who replied on 10 March that he would amend the bill by the “next Meeting of Assembly.” During the third session, on 11 August 1752, the governor returned the bill with amendments, which were accepted on 14 August and ordered to be engrossed with the bill. Members from the assembly and the council compared the bill, and Governor Hamilton enacted it on 22 August. The king in council declared it law on 10 May 1753.11

THE MAJOR ISSUE: PAPER MONEY

Ever since the passing of a paper money bill in 1723, the assembly had financed about half of its expenses through interest arising from the Loan Office. Persons could borrow up to £100 on land at an interest rate of 5 percent, which Franklin estimated on 22 August 1751 generated about £3,000 a year (4:187). Pennsylvania’s assemblymen all knew that since 1748 Parliament had considered passing an act forbidding colonial paper currency because New England’s paper money depreciated so rapidly that the British merchants who accepted it were penalized. But Parliament’s currency act of June 1751 only forbade the New England colonies from emitting any further paper currency.12 The Pennsylvania Assembly believed it could now enact a new paper money bill.

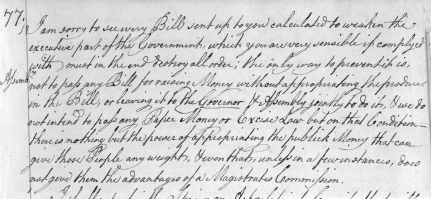

Thomas Penn, however, objected to Pennsylvania’s paper currency bills and to the Loan Office because it made the legislature semi-independent. Penn had resolved to control the province’s finances. He wrote Governor Hamilton on 29 July 1751: “I am sorry to see every Bill sent up to you calculated to weaken the executive part of the Government, which you are very sensible if complyed with must in the end destroy all order; the only way to prevent it is, not to pass any Bill for raising Money without appropriating the production in the Bill, or leaving it to the Governor & Assembly jointly to do it, & we do not intend to pass any Paper Money … but on that Condition—there is nothing but the power of appropriating the publick Money that can give those People [the assemblymen] any weight.”13 Penn’s disdain for Pennsylvanians in general and the Pennsylvania legislators in particular naturally increased their contempt for him.

Penn’s semi-formal instruction to Governor Hamilton was to be kept secret except from the leading Proprietary Party members. Penn also forbade Hamilton to pass any “Excise Law” without the governor sharing in the decision on how to spend the taxes, but the excise duties were not about to expire. They would have to be repealed—and there was little possibility that the assembly would repeal them.14

On 12 February 1751/2, a petition for more paper money was read in the House. The next day it was referred to further consideration. On 14 February, the Speaker ordered that Franklin be one of a “Committee to prepare and bring in a Bill for re-emitting and continuing the Currency of the Bills of Credit of this Province and for striking a further Sum to be made current, and emitted on Loan.” The committee brought in its paper money bill on 19 February but left blank the amount to be struck and made current. That meant the committee members disagreed. After being read the second time with the sum still blank, the House resolved itself into a committee of the whole and voted to make the amount £40,000. Read for the third time on 25 February, the bill passed. The next day it was sent to Governor Hamilton.15

Figure 34a. Thomas Penn’s disdain for the legislators of Pennsylvania, Penn to Governor James Hamilton, 29 July 1751. Writing Governor James Hamilton concerning his secret instructions, Thomas Penn ordered him not to pass any money bills or excise taxes unless they specified exactly what the funds would be spent for or unless the governor controlled their disposition. Then Penn superciliously wrote of the Pennsylvania assemblymen: “nothing but the power of appropriating the publick Money … can give those People any weight.” Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Hamilton vetoed it on 6 March but did not, of course, cite Penn’s instruction. That would have raised an outcry against Penn, the Proprietary Party, and Hamilton. Instead, he said that only by the “strongest Solicitations” were Pennsylvania and the southern colonies exempted from Parliament’s currency act of 1751. He reminded the legislators that Pennsylvania had always shown moderation in the past, and that the most recent emission was only £11,110. He claimed it was inadvisable to ask to re-emit “our Present Currency for a long Term of Years” or to ask for “a new Emission of a larger Sum than was ever at one Time made in the Province.”16 The House appointed a committee, including Franklin, to reply. On 7 March, the committee defended its request. Though the bill for £40,000 would have “tended greatly to the Welfare” of the province, the House submitted a bill for only £20,000 in order “to obviate every Objection.” Reflecting Franklin’s “Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind” (4:229, #10), the message said that the currency would appear to be to “the Advantage of the Trade of our Mother Country, in full Proportion to what we can expect or hope to reap among ourselves.” The committee further stated that the government had only added an inconsiderable sum to the paper currency in the previous twenty years, though “within that Time, the Number of our Inhabitants and our Trade are greatly increased” (4:273–74). The House approved the committee’s message and promptly submitted a revised bill, now requesting £20,000.

Figure 34b. Thomas Penn’s scorn for the Pennsylvania Hospital, Liberty Bell, etc., Penn to Richard Peters, 26 February 1755. To Peters, secretary of the province, Penn complained on 21 February 1755 that the Pennsylvania Assembly spent money frivolously. The assemblymen “pretend no exception can be taken to their having misapplyed Money, I think their Hospital, Steeple, Bells, unnecessary Library, with several other things are reasons why they should not have the appropriations to themselves, all these have arisen since the commencement of the last French War.” The items Penn specified were the Pennsylvania Hospital, the statehouse steeple (finished in April 1753), the Liberty Bell (purchased in 1752, recast and hung in the completed statehouse steeple in 1753), the fire bell (also bought in 1752 and hung in the Philadelphia Academy in 1753); and perhaps the Library Company of Philadelphia. The last, however, may refer to the “Books and Maps” that Isaac Norris and Franklin purchased in 1753 for the use of the Pennsylvania Assembly. Courtesy, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Governor Hamilton rejected it on 10 March 1752, claiming that the “present Bills of Credit will continue to be current for more than four Years, without any Diminution, and the Prices of our Export Commodities, in my Opinion, shew we are not in immediate Want of Money as a Medium of Commerce.” He again cited the Parliament’s act of 1751: “Making the best Judgment I am able of what has lately passed in England, concerning Paper Currencies in America, I cannot see my passing the Bill in the Light the Assembly does, and therefore cannot give my Assent to it.” The next day Norris appointed Franklin to a committee “to enquire into the State of our Paper Currency, our foreign and domestick Trade; and the Number of People within this Province, and report thereon to the next Sitting of Assembly.”17 Since the charge described the kinds of concerns that Franklin addressed in his “Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind,” it seems likely that he proposed the committee. The assembly’s second session adjourned that afternoon to 10 August. Hamilton knew he would hear from the assembly about the money bill in August. That would traditionally be a short session, but he would have to answer the assembly’s renewed request the following winter. Chafing at Penn’s instruction of 29 July 1751, Hamilton wrote him on 18 March 1751/2 that the assembly and even some members of the Proprietary Party would never allow the governor to control the money arising from either paper currency or the excise taxes. To emphasize the impossibility of carrying out Penn’s desires, Hamilton said he had a “great desire to resign.”18

Thomas Penn valued Hamilton’s service and replied on 30 May 1752: “As soon as I received your Letter I waited on his Lordship as I thought it of great Consequence to know whether there was any room to expect such a Bill would pass here.” Penn called upon John Carteret, first Earl Granville, president of the Privy Council. (Granville’s former wife, Lady Sophia Fermor, was the sister of Lady Juliana, Thomas Penn’s wife.) Penn reported that Granville was “much concerned that Pennsylvania” should ask for a large addition to its paper currency so soon after Parliament had passed a law to prevent the issuing of any more paper money in the New England colonies. According to Penn, Granville “compared our Currency with that of Rhode Island, our People and Trade with theirs,” and said “he was sensible there was a great disproportion in the Quantity of Currency in our favor; but much desir’d that if it should be found necessary to increase the Quantity that it should be only a small addition, and that the Bill should not be passed for at least a year, and at the same time that a representative should be sent with it, setting the increase of the Trade of Pennsylvania, and, of its Inhabitants.”

Perhaps Penn reported Granville’s conversation accurately, but I suspect that Penn supplied him only with select facts. Penn wrote Hamilton: “We then spoke of the Sum, when I proposed Twenty Thousand Pounds, for I found more would not be allowed, and I myself you may be assured did not desire to make the Quantity too great.” Penn advised Hamilton to put off the bill and suggested that it could “be done by private Conferences, for this must not be the Subject of a Publick Message, at least no names must be made use of & you will endeavour to do it on the Receipt of this and inform them that I believe a Bill in proper time will be allowed.” The latter part of Penn’s letter adds to one’s suspicion that he made up part of the conversation with Granville, for it has a similar underlying sentiment as the 29 July 1751 letter to Hamilton: “He also said a good deal to me of the great mischief that attended the Assembly having the Power of disposing of the Interest Money, and if any more is issued in the King’s Colonys [i.e., the royal colonies, the Privy Council] will give the same Instructions I have sent you.”

Despite Hamilton’s opinion, Penn continued his campaign to control the colony’s funds. He therefore repeated on 30 May 1752 that Hamilton should not pass a currency bill unless the governor controlled the money.19

THE LAST ASSEMBLY SESSION OF 1751–52, 10–22 AUGUST 1752

When the Pennsylvania Assembly of 1751–52 met in August, it resolved the pressing business and tried to wind up the session, probably knowing it would be impossible to get Governor Hamilton to approve a currency bill. Perhaps, as Penn had suggested, Hamilton had conferred privately with Speaker Isaac Norris and Franklin and asked that the bill be put off for a year. But Franklin had prepared his “Report on the State of the Currency” on 19 August 1752. Franklin’s extraordinary document reflected his “Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind.” He presented a history of the paper money acts since 1723 and pointed out that the £80,000 in paper currency presently in use was to continue less than four years longer, “when it must begin to sink,” one-sixth part per year. In six years the province would be left without any currency, “except that precarious One of Silver, which cannot be depended on, being continually wanted to ship Home, as Returns, to pay for the Manufactures of Great-Britain” (4:345). Shipping and commerce in Pennsylvania were falling in the years before 1723 when the first paper money act passed but since then have “flourished and encreased in a most surprizing Manner.” Calculating Pennsylvania’s population, Franklin cited the bills of mortality and the tax records from Philadelphia through 1751 before considering the population increase in Pennsylvania’s other counties, beginning with Bucks and Chester. Next, he turned to the trade with England, quoting from a report to Parliament of 4 April 1749 by the inspector general of the customs. Like the overseas trade, the commerce within Pennsylvania had increased in proportion to the increasing population (4:348).

Both the manner of issuing the paper currency and “the Medium itself” contributed to its success. Loans from no less than £12.10 to no more than £100 per person, to be repaid in yearly quotas, had “put it in the Power of many to purchase Lands … and thereby to acquire Estate to themselves, and to support and bring up Families.” Without the loans, many “would probably have continued longer in a single State” or remained laborers for others or emigrated. Now the demand for money and for borrowing from the Loan Office had greatly increased, and since more than a thousand applicants were waiting, “a vast Multitude of our Inhabitants have, to procure Settlements, wandered away to other Places.” The increase in population, “great as it is, would probably have been much greater” if more paper currency had been issued (4:348–49). With a touch of irony, Franklin conceded that making it easy “for the industrious Poor to obtain Lands, and acquire Property in a Country” could be charged with keeping up “the Price of Labour.” That made it “more difficult for the old Settler to procure working Hands, the Labourers very soon setting up for themselves.” Thus, despite the number of laborers who have immigrated into Pennsylvania, “Labour continues as dear as ever”—a point made in “Observations” (4:228, #8). Nevertheless, for the old settler, the “Inconvenience is perhaps more than balanced by the rising Value of his Lands, occasion’d by Encrease of People” (4:349–50).

The report ended by paraphrasing the thesis of Franklin’s “Observations”: “by rendering the Means of purchasing Land easy to the Poor, the Dominions of the Crown are strengthen’d and extended; the Proprietaries dispose of their Wilderness Territory; and the British Nation secures the Benefit of its Manufactures, and increases the Demand for them.” Franklin again anticipated Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontier thesis as a reason that American manufacturing could not compete with England’s: “For so long as Land can be easily procur’d … so long will Labour be dear in America; and while Labour continues dear, we can never rival the Artificers … of our Mother Country” (4:350).

When Thomas Penn read the report, he may have conceded that these were all good reasons, especially that money available in the Loan Office made his “Wilderness” lands more valuable, but he thought it more important to curb the power of the assembly—which he intended to do by cutting off its funds. Presented to the Pennsylvania Assembly on 20 August 1752, Franklin’s report was referred on 22 August to the following assembly of 1752–53 for consideration. Richard Peters reported to Thomas Penn that some members of the assembly had begun to say that Hamilton’s excuses were subterfuges and that the proprietors had forbidden him to pass a paper currency bill.20 Franklin must have heard these rumors and probably believed them true. Like other assembly members, Franklin evidently thought Thomas Penn was more concerned with his own power than with Pennsylvania’s welfare. On that same 22 August, the finance committee, which included Franklin, settled the annual accounts, and the session adjourned.

Though Franklin was involved only as an assemblyman, two other acts and a minor item of the assembly of 1751–52 are of interest. On 12 February the assembly requested “That the Superintendants of the State-house do provide a suitable Ink-stand of Silver for the Use of the Speaker’s Table.” Philip Syng made the elaborate silver inkstand, for which the assembly paid the high price of £25.16 at the session’s end. Used in signing both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, Syng’s ink stand is displayed today at Independence Hall. The two acts created new counties. On 20 February, the House passed the bill forming Berks County and the next day passed a bill creating Northampton County. Governor Hamilton approved them on 11 March 1751/2.21 Each county, however, was given just one representative, whereas the oldest counties each had eight. Both the boundaries of the two new counties and the number of representatives allowed were a gerrymandering attempt to keep the Quaker Party in power and to restrict the German influence. Years later, the Paxton Boys identified the unfair representation in the Pennsylvania Assembly as a major grievance and, somehow, a partial excuse for the murder of innocent Indians.

Other than official occasions with the assembly and the other organizations that Franklin belonged to that kept minutes, little is known of Franklin’s and Deborah’s social life. One tantalizing reference is his thank-you letter to Susanna Wright (1697–1784). She was the daughter of Franklin’s friend John Wright, who died in 1749, and sister of John (1711–59) and James (1714–75), both of whom, like their father, served as representatives to the General Assembly. Franklin wrote her on 21 November 1751 that “Your Guests all got well home to their Families, highly pleas’d with their Journey, and with the Hospitality of Hempstead.” Franklin, Deborah, and perhaps William and Sarah, together with some other person(s), had all visited Susanna Wright at her home on the Susquehanna, Lancaster County, where she owned a ferry and land. She never married, but Samuel Blunston (1689–1745), another former Lancaster County representative, left her a major part of his vast estate and is known to have asked her to marry him.22 A feminist, fine poet, active political figure, and an advocate of Americanism, she was probably the most intellectual woman whom Franklin had met to that date.

With his thank-you letter, Franklin sent “Susy” Wright a gift of superior candles, which he said she would especially prize since they were “the Manufacture of our own Country” (4:211). He also gave her a copy of the latest Gentleman’s Magazine because of its article and illustration of the “Marble Aqueduct” in Portugal. He evidently knew that she would be interested in such engineering feats. Franklin is said to have written an “Ode on Hospitality” about the stay at Hempfield, but it seems not to be extant. Franklin valued her friendship and capabilities. Four years later, Franklin consulted her about securing wagons for General Edward Braddock. Deborah Franklin was among Wright’s friends and correspondents.23

CONCLUSION

During the assembly of 1751–52, Franklin had thirty-six assignments—the most of any member.24 In his first full year in the House, he had become, after Speaker Isaac Norris, its most influential member. Though Proprietary Party members still hoped that Franklin would identify with Penn and the administration, he was already the foremost spokesman of the moderate wing of the Quaker Party. Like most assemblymen, Franklin despised Thomas Penn for attempting to deprive Pennsylvanians of the ability to control their own government and the funds it raised.