![]()

The characters in this true-life story come from diverse backgrounds, some local, others from overseas. They have a range of personalities and a mix of training, skills and lifestyles. The one connecting thread that has pulled them all together in Shark Town is a passion for the sea and the Great White shark.

Scientist Alison Towner at work doing what, for her, is the best job in the world.

Hennie Otto

In the Jordanian Red Sea port and resort city of Aqaba the sun was setting as the muezzin called the faithful to prayer. At the dining table in her small flat overlooking the sea, a young British scientist tapped away at her computer keyboard, typing an application for a job, while silently offering up prayers for good luck with her quest.

Alison Towner was a marine biologist with an obsession for sharks and, in particular, for Great White sharks. After finishing school in Manchester, she attended Bangor University in north Wales and did a degree in marine biology. With her degree in her pocket, she soon relocated to Aqaba to work as a dive instructor for a Jordanian company.

Now she was applying for what she considered to be her dream job – researching Great White sharks in South Africa. Dyer Island, offshore from Gansbaai, was the acknowledged global Great White hotspot, and Wilfred Chivell’s Marine Dynamics and Dyer Island Conservation Trust organisations were looking for a research scientist.

Alison Towner – marine biologist, shark enthusiast.

Hennie Otto

As she typed, she had a feeling deep down that she would get this job – although she hardly dared dream for fear of jinxing her chances in life’s great job lottery.

Wilfred Chivell, Shark Town entrepreneur.

Brenda du Toit

The Red Sea was beautiful, and while working as a diving instructor, based in the port city of Aqaba, she had developed affection and respect for the Jordanian people. If she got the job she would be sad to leave, but the lure of the Great White shark outweighed the fun she was having in Jordan. She shut down her computer, then closed and covered it with a small towel to protect it from the dusty environment. She could have closed her doors and windows and lived in the much cleaner air produced by her air conditioner – but when you are born in the north of England, you savour and appreciate sun and warm climates, and don’t want to look at the world through glass if there are other options.

![]()

Sadly, Alison’s father had passed away when she was only five years old, but there had been enough time for his influence on her to be telling. He was a writer for the Manchester Evening News and had harboured a lifelong passion for the sea and its creatures. He had written a book, an unpublished, Hemingway-style novel called The Last Magical Fishing Trip, that underlined his intense marine interest. One of his ambitions had been to see a Great White shark – an ambition that he hadn’t lived long enough to achieve, but one that would inspire his daughter and set her on her eventual career path.

![]()

Two days after sending her job application to Wilfred Chivell, an email came back in response. Alison’s fingers hovered over the keys while her mind fizzed with excitement – and prepared for disappointment. She clicked on the message and her eyes raced along the lines of the reply – her optimism had paid off, and she would soon be on her way to South Africa and the ‘Great White shark capital of the world’.

She gave notice to her Jordanian employers and was soon heading south to fulfil her ultimate shark dream. Her mother had been nervous when Alison went to Jordan; now she was concerned again due to South Africa’s reputation for being unsafe. But for Alison, nearly everything in her world was wonderful. Her only regret was that her shark-mad father wasn’t there to share her happiness – he would have been so proud.

Alison’s first 13 years in South Africa would be marked by great adventure, research and fun: she was realising her dream, and was making meaningful and valuable contributions to Great White shark science. But it would be two Killer whales that would make her a familiar face and name in marine circles around the world.

‘THE GREAT WHITE SHARK CAPITAL OF THE WORLD’ – quite a claim to live up to.

Richard Peirce

Boats packed with ecotourists had become the daily norm, but soon a new reality would threaten to change everything.

Richard Peirce

![]()

One might imagine someone who had been a diamond diver and a successful antiquities underwater treasure hunter to look like a cross between Johnny Depp as a pirate, Jacques Cousteau and Indiana Jones. Wilfred Chivell doesn’t conform to this – or to any other stereotype. Wildlife – mainly marine – and its conservation is his abiding passion. Detractors would say he can be gruff and abrupt; fans would excuse this by saying he is single-minded and doesn’t suffer fools gladly. If they could speak, the sea and its animals and birds would say ‘thank you’.

Chivell’s grandfather was born in Cornwall in the UK. Traditionally, the Cornish made their livings from agriculture and tin mining, and at sea from fishing and serving on ships. The Cornish are a fiercely independent and tough people, and to this day many consider Cornwall to be part of Britain rather than part of England – it is, after all, the only English county with its own flag and language. Wilfred Chivell may be a third-generation South African, but his family’s Cornish background is still very much in evidence in his character and behaviour. He was born near Caledon in South Africa’s Western Cape, where the family lived on a small dairy farm and were the main milk suppliers to the people of Gansbaai. Wilfred worked on the farm from his earliest years, and his father was a hard but fair taskmaster. He attended school in Gansbaai up to Grade Nine, and at 15 years old went to agricultural high school in Paarl as a boarding student. After school he did his four years’ National Service in the police force, then went home to decide on what future path to follow.

A born adventurer, he soon spread his wings and spent the next few years diamond diving in Namibia, as well as wreck diving and spearfishing. Soon after the death of his father in 1981 he returned home to Gansbaai and started a small factory making bricks and blocks for building.

Then, on 1st January 1987, while out spearfishing with a friend, there came a real break: in shallow waters off Gansbaai, Wilfred found a cannon and other artefacts suggestive of a shipwreck. Instinct told the men this wreck was a significant find and, before returning to shore, they made careful note of its exact position. They went home with a roll of lead they had brought up from the seabed, and a piece of copper plate with the impression of a coin stamped on it. They sought advice from an experienced wreck diver in Gansbaai, who suggested they had found the Nicobar – a Danish ship that had foundered and sunk in 1783, and whose treasure had lain undiscovered all these years. A long process followed during which they registered the wreck, salvaged all they could and learnt everything possible about the value of their find.

In 1989 Wilfred, his friend and their archaeologist partner sold the coins from the wreck and each made several hundred thousand rand, which gave them the means to do what they wanted in life. Wilfred expanded his businesses, married and prospered. Then, in 1999 a difficult financial position in South Africa forced interest rates up to well over 20 per cent. The building industry was hit hard. Wilfred had always used all his money to expand, so he had no reserves. Companies that owed him money collapsed and went out of business, his cash flow dried up, and servicing his loans at such high interest rates became impossible. He was squeezed on all sides and foreclosure by the banks became inevitable. One moment, he ruled the world and was going forward like an express train, and the next, events beyond his control caused total financial collapse. In order to pay off the roughly 200 people who had been working for him, he sold everything he could, including his house. He had taken a very hard knock and it took a while to adjust mentally to the new realities, but adjust he did. Wilfred Chivell is not a man who stays down for long or has time for self-pity.

His wife had moved out and he was left with a bed, a TV, a chair, a fax machine, an old Land Rover and an inflatable boat. The boat was to be the key to the next stage in Chivell’s life, when he started a company called Dyer Island Cruises and began taking tourists out whale watching, and to the Dyer Island seal colony. He began a process of putting himself back together again, and by 2005 he had bought a cage-diving company for viewing sharks underwater, called Marine Dynamics. The company was a significant cash generator, but Wilfred continued to run his valued whale-watching business in parallel. He loved and treasured the local environment and its wildlife, and recognised that both faced serious threats and challenges. This led him in 2006 to establish a conservation Non-profit Organisation (NPO) called The Dyer Island Conservation Trust (DICT). Then, in 2015, a decade after he had started with Marine Dynamics, he opened the African Penguin & Seabird Sanctuary, which is an affiliate of the DICT.

Hennie Otto

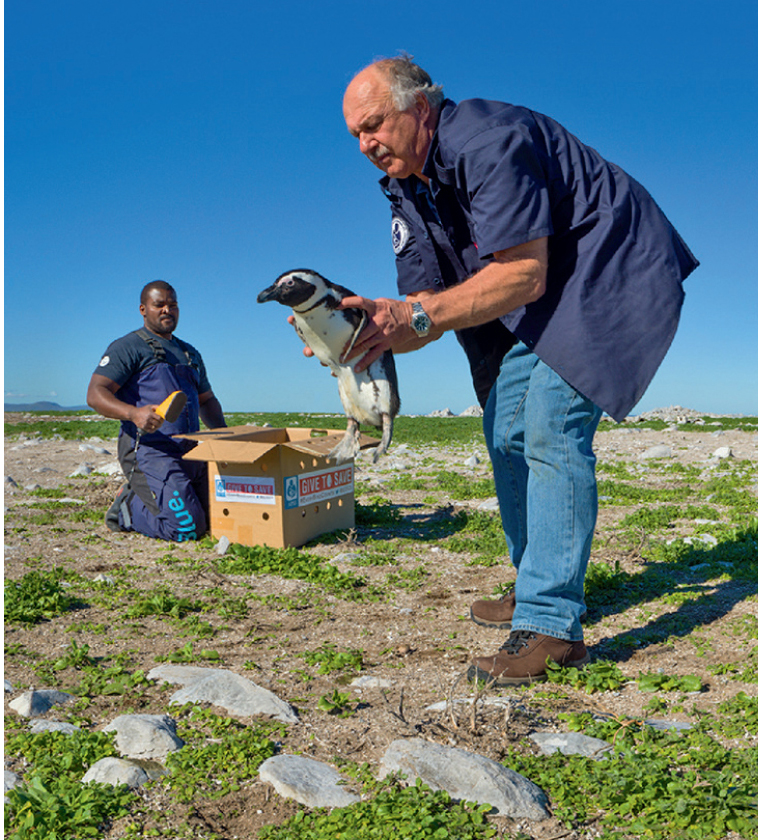

The African Penguin & Seabird Sanctuary near Gansbaai.

Hennie Otto

Wilfred Chivell releasing a rehabilitated bird.

Francis Assadi/Panotriptych™

By now Wilfred Chivell was the biggest employer and, arguably, the most significant figure in the local marine sector. However, despite his success and the security that came with it, his financial crash of 1998 was ever present in his mind. He had learnt a very hard lesson and had learnt it well. Never again would he operate without cash reserves, and never again would he leave himself financially vulnerable. He knew that uncertainty and the unexpected were always waiting around the corner to ambush the unwary. What he didn’t know was that two giant ocean predators were approaching and that they would threaten to destroy everything he had worked for.

![]()

Brian McFarlane’s family has lived in and around Hermanus for six generations, ever since his great-grandfather, Walter McFarlane, arrived in South Africa from Scotland and started operating two fishing boats out of the old harbour in Hermanus. Brian’s father was among the first to be involved in the abalone industry, and his first mini-factory was located in the family kitchen.

When Brian left school, it was not surprising that the sea called, and that he answered. He spent the first 20 years of his working life diving for diamonds, shipwrecks and abalone, or catching fish, and among the fish he caught were Great White sharks.

Cage diving with Great Whites was started in the late 1990s by Theo and Craig Ferreira, and the potential of this new form of ecotourism was quickly recognised by others. ‘Shark Lady’ Kim Maclean followed the Ferreiras and, before long, Brian McFarlane also started taking Great White fans out to Dyer Island. His first cage-diving boat could take six people, and he crewed alone; he charged R300.00 a head, and did one trip a day. His operation grew steadily, and after 20 years he ran a much larger vessel with a crew of five, taking up to 40 shark watchers on each trip, and in high season doing three trips a day.

The McFarlane family has been part of the fabric of the area for six generations.

Great White Shark Tours

McFarlane called his company Great White Shark Tours, and its success and growth were an accurate reflection of the success and growth that cage diving had brought to Gansbaai, Kleinbaai and the wider area. In addition to the boat crew, his company employed another 18 people on shore doing marketing, administration, cooking, catering for guests, and performing various maintenance functions.

By 2014, the day-to-day operation of the boat was being handled by Brian’s son who had grown up alongside the cage-diving industry. Down the years, generations of the family had had to strategise and struggle daily to make a living from the sea. Cage diving changed this: weather permitting, it provided a daily, year-round, money-making opportunity for the McFarlanes and for all those involved directly and indirectly in Great White ecotourism. It was a far cry from the harder, riskier lives led by the McFarlane forebears. As long as there were sharks, there would be tourists, and livelihoods would be safe. Or would they?

![]()

In 2000, 30-year-old Dave Caravias from England first visited Gansbaai to fulfil a long-held dream to see a Great White shark. Dave had only a few weeks earlier started a new job in Johannesburg – a three-month contract with a British-based IT consultancy. But now the hand of fate was hovering over the young English shark fan, and he could never have foreseen how unfolding events on this day would influence the course of his life.

He spent a wonderful morning out at Dyer Island with skipper and seasoned operator Jackie Schmidt, followed by lunch at a Gansbaai restaurant. Over lunch in Gansbaai, his gaze kept being drawn to a pretty young waitress who, quite unawares, held him spellbound. It so happened that a rugby match between South Africa and England was showing on TV. Dave saw a chance, called her over and proposed a wager with her: if England won she would go on a date with him. There was no agreement as to what would happen if South Africa won! – but there didn’t need to be because England won the match, Dave won the bet and a date with Elna, who would later become his wife. That day, everything changed; he had fallen in love with a beautiful girl, with a new country, and with Great White sharks.

Dave’s original assignment stretched to over a year before his company told him, in early 2002, that he was being sent back to the UK. However, by this time Dave had become entrenched in South Africa, which had become home and was where he saw his future. He handed in his notice and, together with Elna, started to look for ways to make a living in his adopted country. The shark cage-diving industry seemed a promising field, and so he and Elna decided to open a guesthouse offering accommodation to visiting cage divers.

A loan from Dave’s UK bankers allowed them to buy a plot of land on Ingang Street in De Kelders, a village next door to Gansbaai, and they constructed an interesting circular building for use as a guesthouse, which they named the Roundhouse. He was a shark fan, his target customers were shark fans, and it felt appropriate that he should enter the shark-related market. He approached cage-diving operators to make sure they knew there was now a guesthouse offering services specifically tailored to the needs of their clients.

The Roundhouse, Dave Caravias’ guesthouse in De Kelders.

Richard Peirce

The response was encouraging but bookings only really took off in September 2003 when Dave set up his own booking agency. Sharkbookings.com was initially conceived to facilitate bookings for the Roundhouse, but it quickly expanded and developed into an agency covering shark-diving destinations right up southern Africa’s eastern coast, all the way to Mozambique.

The Caravias family flourished and expanded with the birth of their two daughters. Dave didn’t regret his decision to move to South Africa. He had built a successful new life in a place he loved and now called home, and this new life involved him with the sharks he had dreamt of since he was a child.

Dave Caravias fatbiking with clients in dunes near De Kelders.

Dave Caravias

The sharks brought him visitors from all over the world and accounted for over 90 per cent of those who stayed at the guesthouse. As long as there were sharks, there would be visitors. It never occurred to him that the sharks might one day disappear.

![]()

Christina moved to Gansbaai in 1990, where she met and married commercial fisherman Frank Rutzen. Her new husband skippered his own boat, and Christina enjoyed going out fishing with him daily, until her pregnancy with their first child put an end to her trips.

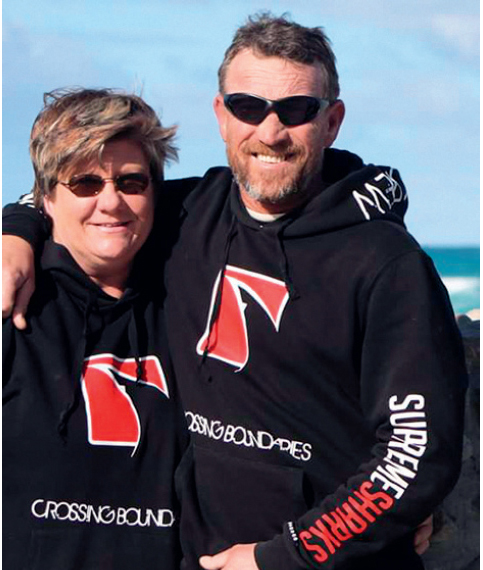

Frank and Christina Rutzen, committed townspeople.

Jurie Smal

In 1996 Frank started working with skipper Jackie Schmidt on his cage-diving boat and, like so many others in Gansbaai, the Rutzen family’s future became tied to the fast-expanding cage-diving ecotourism industry. Although Christina was a full-time mother, she undertook various jobs supporting cage-diving operators, and then became manager in a local restaurant. In 2008, she applied for a job running the newly created harbour master’s office in Kleinbaai, the little port where the cage-diving operators launch their boats – and she got it. Now harbour master, she was an integral part of the daily life of all Shark Town’s operators. The whole Rutzen family were, in one way or another, involved with Great White sharks: Frank as a cage-diving skipper, Christina running Kleinbaai’s harbour, and Frank’s brother Mike working on cage-diving boats – until he got his own operator’s licence and became world-famous as a free diver with Great Whites.

Storm clouds over Walker Bay.

Stanley Carpenter

![]()

For the Rutzens, when the new decade began in 2010, life and work were up and running. There were no apparent dark clouds on the horizon for the hard-working citizens of Shark Town. There was no way anyone could have forecast that, within a few years, storm clouds would gather that would shatter the future they had thought to be secure.