In defeated Germany just after World War I, any arguments for or against the ground-attack and dive-bomber aircraft as opposed to the traditional high-altitude level bomber were perforce purely academic. Shorn of all offensive weaponry by the 1919 Treaty of Versailles, Germany’s arms manufacturers were expressly forbidden from producing any replacements. The ink was hardly dry on the hated Diktat, however, before companies began seeking ways to circumvent the strictures imposed upon them.

One such firm was the Dessau-based Junkers Flugzeugwerke AG which, in the early 1920s, set up the Swedish subsidiary AB Flygindustri at Limhamn-Malmo. Here, they were free to concentrate on military, rather than civil, aircraft production and development. Among the types built at Limhamn was a highly advanced two-seat fighter. Designed by Dipl.-Ing Karl Plauth and Hermann Pohlmann, the two Junkers K 47 prototypes, which first flew in 1929, were subsequently evaluated at the clandestine German air training centre at Lipezk, north of Voronezh, in the Soviet Union.

While a batch of 12 production K 47 fighters was completed in Sweden for export (six being supplied to the Chinese Central Government and four ultimately going to the Soviet Union), the Reichswehr purchased the two prototypes, plus the two remaining export aircraft. Found to be capable of carrying a 100kg bomb-load (eight 12.5kg fragmentation bombs) on their underwing struts, three of these machines were tested at Lipezk for their suitability in the dive-bombing role. Although successful, high unit costs precluded the tightly budgeted Reichswehr from awarding a production contract, and the four aircraft (now designated as A 48s) served out their time in the Reich engaged in a variety of quasi-civil duties.

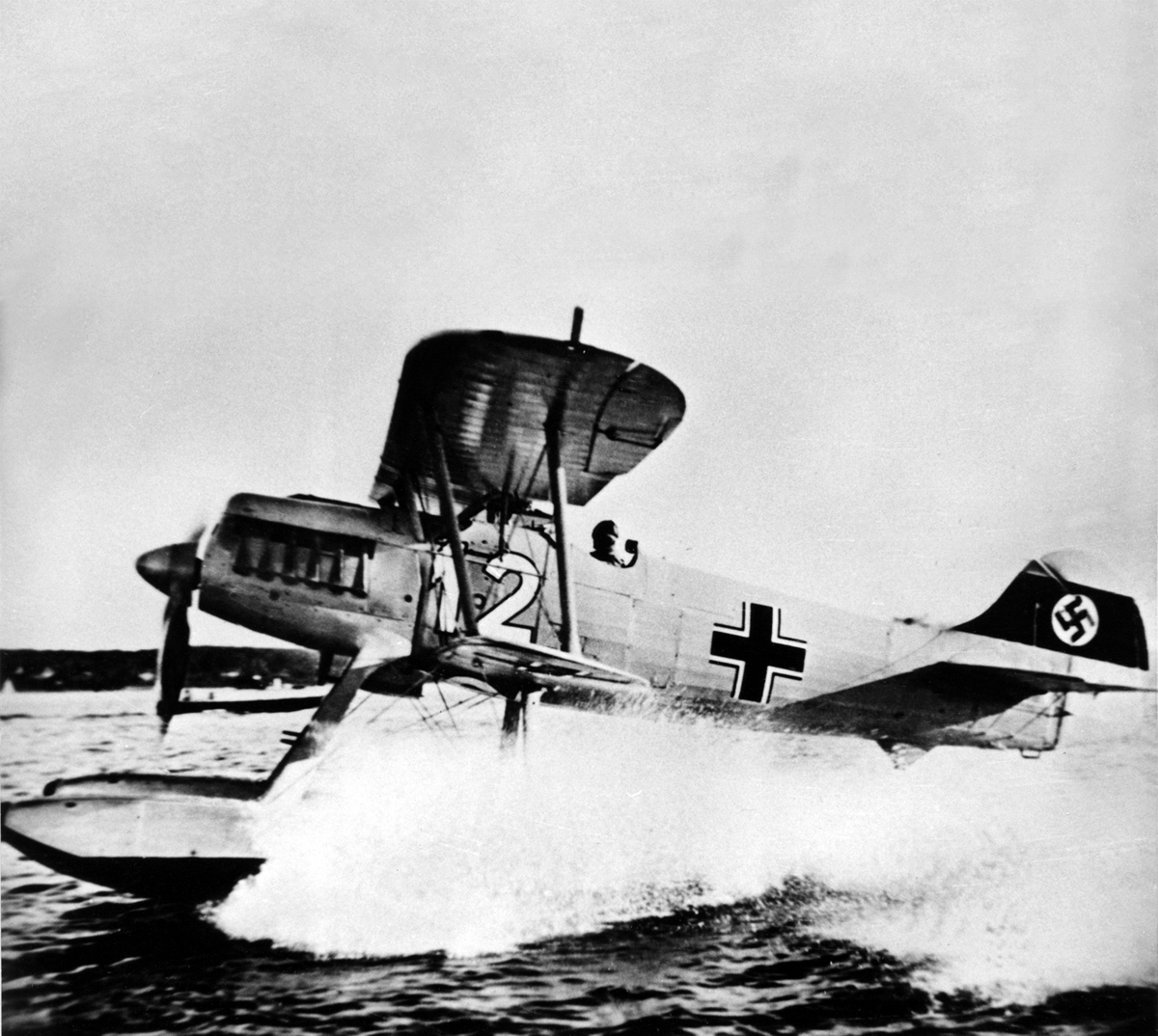

The seed had nevertheless been sown, and in the predatory shape of the original K 47 – despite the uncranked wing and twin tail unit – the embryonic form of the wartime Stuka, what would become the Luftwaffe’s most infamous ground-attack aircraft, could already be seen emerging. A further two aircraft were to play a part in the story of German dive-bomber development before the advent of the Junkers Ju 87. The first of these came about as a direct result of growing Japanese interest in dive-bombing. Although an erstwhile ally of the Western Powers during World War I, Japan herself was now also restricted by international treaty in the number and tonnage of the capital ships she was permitted to build (a ratio of three-to-two in favour of the United States and Great Britain). Seeking ways to redress the balance, and keenly aware of the ongoing dive-bomber experiments being conducted by the US Navy across the Pacific, Japan turned to Germany for assistance, approaching not Junkers, but the reputable seaplane manufacturing firm of Ernst Heinkel AG.

Hs 123A ‘Black Chevron/Yellow L’ of II./SG 2, Khersonyes-South, Crimea, April 1944. Incredibly, what must surely have been the last remaining operational examples of the venerable Hs 123 reappeared on Luftflotte 4’s order of battle late in April 1944. According to that document, they were assigned to II./SG 2 and based alongside the Gruppe’s Fw 190s during its final days on the Crimean peninsula. Note the percussion rods fitted to the 50kg SC 50 bombs. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

The resulting two-seater biplane design stressed for diving, and initially equipped with floats, was later exported to Japan as the Heinkel He 500, and served as the basis for the Imperial Japanese Navy’s own Aichi OIA carrier-borne dive-bomber.

Heinkel then offered a second (landplane) prototype to the Reichswehr. After a demonstration at the Rechlin test centre in 1932, followed by trials at Lipezk, the type was accepted into service as the He 50A interim dive-bomber in 1933, the year that Adolf Hitler came to power. It was thus the Reichswehr under the aegis of the Weimar Republic, and not the new National Socialist regime, which was responsible for preparing the groundwork and introducing the dive-bomber and ground-attack aircraft into Germany’s covert, but burgeoning, new armoury. However, Hitler and the head of his still clandestine air force, Hermann Göring, were more than willing to tread the path already laid down for them. Thus, when World War I fighter ace turned international stunt pilot Ernst Udet came back from a tour of the United States in the early 1930s extolling the virtues and dive-bombing abilities of the Curtiss Hawk II fighter then being offered for export, Göring authorized the newly established RLM to provide Udet with the necessary funds to purchase two examples of the type for use in his aerobatic displays. It was a shrewd move, for not only did it give German designers the opportunity to examine state-of-the-art American technology, but it also acted as a bribe in tempting the ‘freebooting’ Udet back into the official Luftwaffe fold.

A moment of fun and fraternization. The pilot and ground crew of a Ju 87 flirt with a group of Norwegian female skiers while they arm the Stuka.

The dual-role capability of the Curtiss machines prompted the Technisches Amt (Technical Office) of the RLM to issue similar specifications in February 1934 for a single-seat fighter and dive-bomber. The winning design, in the shape of the Henschel Hs 123, made its public debut at Berlin-Johannisthal in May of the following year. Flown by Ernst Udet himself, its performance did much to strengthen the hand of the pro-Stuka (i.e. dive-bomber) lobby within the RLM. Yet, if one discounts its early days in Spain, the Henschel was destined never to see action as such. Throughout the whole of its long operational career – it was still flying on the Eastern Front in 1944 – the ‘eins-zwei-drei’ or ‘one-two-three’, was employed to great effect as a low-level close-support aircraft. For despite being the first Stuka design to be ordered in any quantity for the Luftwaffe, the Hs 123 was regarded from the outset as a ‘Sofort Lösung’ – an ‘immediate solution’ or temporary measure – to bridge the gap until the second, and final, phase of the dive-bomber programme produced a more advanced two-seater machine, offering an improved performance and heavier bomb-load.

To this end, the RLM turned back to Dipl.-Ing Hermann Pohlmann of Junkers, co-designer of the original K 47 (Karl Plauth had lost his life in a flying accident before the K 47 was completed). Pohlmann had begun design work on the Ju 87 on his own initiative back in 1933 when the subject of a second phase to the Sturzbomber-Programm had first been broached. By the time the official specification was finally issued some two years later, he had already commenced the construction of three prototypes, leaving rival firms Arado and Heinkel well out of the running.

Although obviously a product of the same stable as the K 47, the early Ju 87s were, by contrast, particularly ugly and angular aircraft, characterized by the inverted gull wing which would be the hallmark of every one of the 5,700+ Stukas built. However, the Ju 87 had been designed to fulfil a specific role, and in this it was unsurpassed, even if (when it was in its natural element swooping almost vertically on its intended target) it was likened somewhat fancifully to an evil bird of prey.

The first prototype Ju 87 V1, powered by a Rolls-Royce Kestrel V12-cylinder, upright-Vee, liquid-cooled, engine, featured a twin-tail unit not dissimilar to that of its K 47 predecessor. However, when this failed in flight during a medium-angle test dive, causing the V1 to crash, the remaining prototypes were redesigned with a centrally mounted single fin and rudder assembly.

A fourth prototype was later added to the first three, this, the Ju 87 V4, incorporated all the lessons learned from flight-testing the original trio. With its Junkers Jumo 21 OAa inverted-Vee engine in a revised, lowered, cowling to improve forward visibility, re-contoured cockpit canopy and enlarged vertical tail surfaces, the V4 led directly to the first batch of fully armed Ju 87A-O pre-production models, which started coming off the assembly line before the end of 1936. These in turn were followed during the course of 1937 by the A-I and A-2 production runs, the latter being equipped with the uprated Jumo 210Da engine.

In 1938, hard on the heels of the last ‘Anton’ to be built, there appeared the first of the ‘Bertas’: when compared to the Ju 87A, the B-model featured not just a more powerful Jumo 211 engine with direct fuel injection, but a completely redesigned and reconstructed fuselage, cockpit and vertical tail. The most striking difference between the two, however, was the abandonment of the Ju 87A’s huge ‘trousered’ undercarriage in favour of the slightly less obtrusive, and therefore aerodynamically cleaner, spatted leg. Both aircraft, alongside other nascent Luftwaffe ground-attack aircraft, were soon to receive their first combat testing.

The outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in the summer of 1936 afforded Hitler the ideal opportunity to test the mettle of the men and machines of his new air arm under operational conditions. He lost little time in despatching the first units of a volunteer force, soon to evolve into the Legion Condor, to fight alongside the insurgent Spanish Nationalist troops commanded by General Francisco Franco.

A trio of early Hs 123s were among the first aircraft to be sent to Spain. Arriving in the autumn of 1936, they were formed into the Stukakette of VJ/88, the Legion’s then still experimental fighter component. Commanded by Leutnant Heinrich ‘Rubio’ Brücker, the three Henschels first saw action in support of the Nationalist offensive against Malaga in January 1937. They were then transferred northwards to participate in the attacks on the so-called ‘Iron Ring’ defences around Bilbao on Spain’s Biscay coast.

However, it quickly became apparent that the Hs 123 left a lot to be desired as a dive-bomber, for Brücker and his pilots were unable to achieve the level of pinpoint accuracy that had so impressed Ernst Udet during the Hawk II’s demonstration in America six years earlier. The reason for this, it was now discovered, was the Henschel’s inability to maintain sufficient steadiness during the dive.

The Legion’s chief of staff, Oberstleutnant Wolfram Freiherr von Richthofen (cousin of the legendary Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen of World War I fame) therefore decided to employ Brücker’s small unit in the non-diving ground-attack role. And in this they were to prove highly successful. Three more Hs 123s arrived in Spain in the spring of 1937, and ‘Rubio’ Brücker’s now six-strong command set about the business of re-inventing and perfecting the type of low-level ground-attack sorties that had last been flown against the ‘Reds’ in Latvia nearly two decades before. Brücker’s pilots were soon reporting that the ‘fearsome noise alone’ of the Henschels roaring only a matter of metres above the enemy’s columns and positions was often enough to cause panic and confusion – sometimes even flight. It was a tactic which would be repeated to great effect during the opening months of World War II.

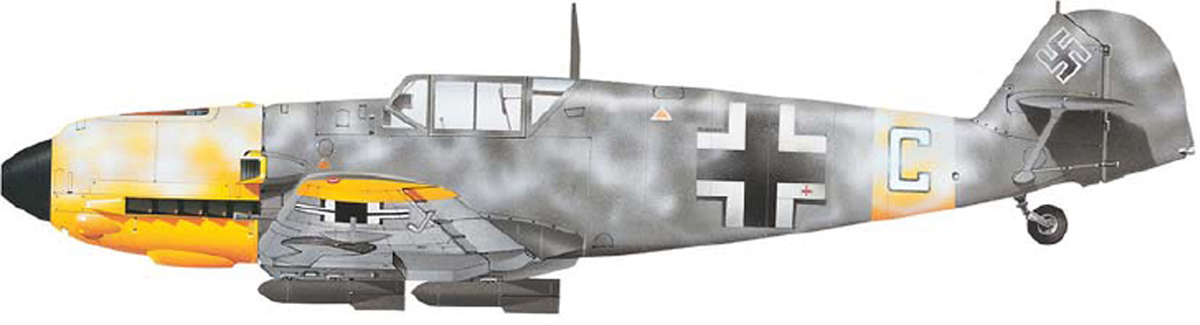

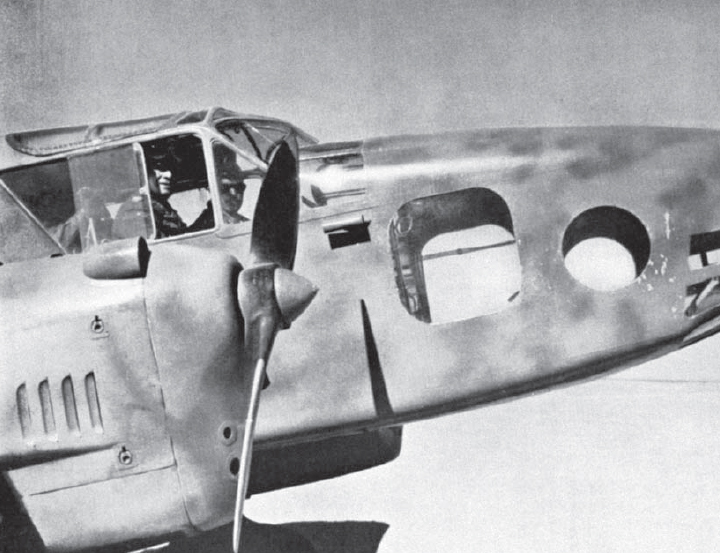

An Me 109 seen outside its hangar in 1940. The Me 109 proved to be a flexible platform, switching readily between fighter and ground-attack roles when necessary.

He 51B ‘2.78’ of Oberfeldwebel Adolf Galland, Staffelkapitän 3.J/88, Legion Condor, Calamocha, Spain, January 1938. Wearing one of the many non-standard green and brown camouflage schemes applied ‘in the field’ after the He 51s had first arrived in Spain (in overall pale-grey finish), ‘2.78’ was Adolf Galland’s preferred mount for most, if not all, of his time at the head of 3.J/88. Like many of the Legion’s fighter pilots, he personalized his machine by embellishing the black fuselage disc – in his case outlining it thinly in white and adding a large Maltese cross. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

Despite the Henschel’s inherent ruggedness, these early ‘experimental’ missions cost the unit dearly. By the summer of 1937 it had lost four of its number, and the following year the two survivors were passed to a Spanish mixed Grupo. During their service with the Legion Condor the Hs 123s had somehow acquired the nickname ‘Teufelsköpfe’ (‘Devil’s Heads’). Oddly, after transfer to the Spanish Nationalist air arm, which subsequently took delivery of a further dozen improved B-1 models, the Henschels were rechristened ‘Angelitos’ (‘Little Angels’)!

However, the Hs 123 was not the only machine to have its operational deficiencies brought to light by service in Spain. The Heinkel He 51 was to prove an even greater disappointment to the German command. Selected as the standard single-seat fighter of the newly emergent Luftwaffe, the Heinkel biplane had already displayed its gracefully aggressive lines to the World’s press in a number of carefully staged demonstrations and fly-pasts long before the first six examples of the type were shipped to Cadiz, in southern Spain, in August 1936.

He 46C ‘1K+BH’ of 3. Störkampfstaffel/Lfl. 4, Eastern Front, Southern Sector, c. April 1943. The He 46 tactical reconnaissance machine, first flown in 1931, was typical of the elderly types equipping the early night ground-attack Staffeln on the eastern front. This particular example – tactical number ‘8’ – is carrying 50kg SC 50 bombs (fitted with tail screamers) on its ventral rack and wing support struts. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

Here, reality turned out to be very different from the image of Luftwaffe superiority fostered by the propaganda-fuelled aerial parades above the rooftops of Berlin. Despite a few initial successes, it came as a rude shock to discover that the He 51 was, in fact, dangerously inferior to the majority of the (mainly French) fighters flown by their Republican opposition. This was brought forcibly home by an incident in mid-September when just two Republican machines escorting a gaggle of elderly Breguet bombers were able not just to prevent six Heinkels from attacking their charges, but actually to drive the German fighters off! It was only the poor armament of the French aircraft which prevented matters from becoming even worse.

At first the Germans tried to remedy the situation by sheer weight of numbers, and by the end of November a further 72 Heinkels had been despatched to Spain (including 24 to the Spanish Nationalist air arm). However, the arrival in Spain of the first Soviet I-15 and I-16 fighters that same month finally dashed any lingering hopes the German Command may still have been harbouring that in the He 51 – which now equipped all four Staffeln of the Legion’s J/88 fighter Gruppe – they possessed a fighter aircraft of world-class standing.

By the close of the year the position of the German fighter force in Spain was being described as ‘farcical’, and the humiliation of its pilots was well nigh complete. Hopelessly outclassed as an air-superiority fighter, the He 51s could not even be gainfully employed on bomber-escort duties. It was reported that upon the approach of enemy aircraft the German fighters were often ‘forced to take refuge within the bomber formations in order to gain the protection of the larger machines’ defensive machine-gun fire’. However, just like the shortcomings of the Hs 123 as a dive-bomber, which soon faded from memory with the advent of the lethally effective Ju 87, so the He 51’s near total inadequacy as a fighter was quickly forgotten upon the appearance of its successor – one of the true greats in the annals of fighter history, the Messerschmitt Bf 109.

In the early spring of 1937 the first Bf 109Bs were rushed to Spain, where they re-equipped 2.J/88. The question now was what to do with the Legion’s He 51s? It was decided that the 2. Staffel machines replaced by the Bf 109s, plus those of the disbanding 4.J/88, would be passed to the Spanish Nationalists, while the aircraft of 1. and 3.J/88 – pending the arrival of more Messerschmitts – would be redeployed mainly in the ground-attack role.

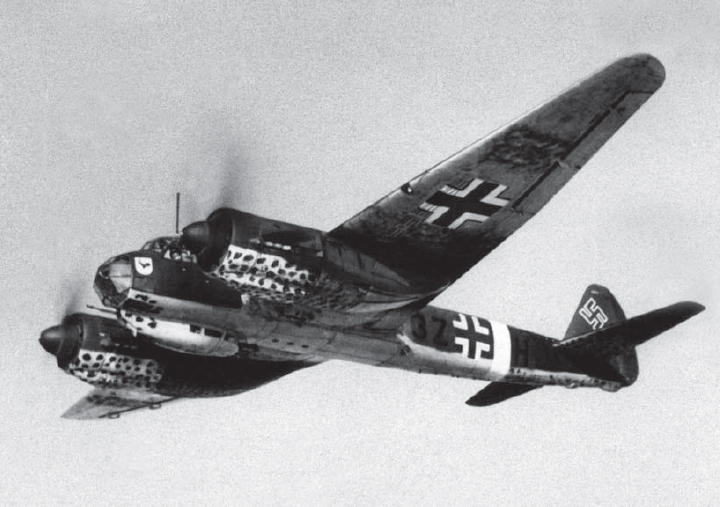

A Ju 88A-14 was a close-support version of the prolific German medium bomber. Armed with a 20mm MG FF cannon in a pod under the fuselage, it could destroy many tanks and all soft-skinned vehicles.

The Spaniards had already begun to use their Heinkels for such missions. Indeed, it was they who developed the Cadena, or ‘chain’, tactic, which consisted of a formation of He 51s, flying in line-ahead, diving upon an enemy trench and machine-gunning along its length one after the other. When the leader had completed his run he would pull up into a steep half-roll and rejoin the end of the queue. The result was that the occupants of the trench were pinned down by continuous fire. The onslaught would be kept up until either the Heinkels’ ammunition was exhausted, or the position was captured by attacking forces. The pilots of 1. and 3.J/88 employed similar tactics during their first ground-attack sorties around Bilbao and Santander on the northern front in the spring of 1937. They also added a ventral Elvemag weapons rack to enable each machine to carry six 10kg bombs.

Meanwhile, the Ju 87 was also forging its reputation as a formidable dive-bomber and ground-attack aircraft. The experience gained from the handful of Stukas sent to participate in the Spanish Civil war was indeed invaluable. Air and ground crews alike practised and perfected their skills and techniques, equipment was honed and numerous modifications made. The Ju 87 proved its ability to hit a precision target from a near-vertical dive, installing terror via the B-1’s ‘Jericho-Trompete’ (‘Jericho Trumpet’) dive sirens, or the whistles fitted to its bombs. However, one ingredient had been lacking – serious opposition. In the air the Ju 87s enjoyed strong fighter protection, whilst effective Republican AA fire was almost non-existent except in the immediate vicinity of those targets deemed to be vitally important. A great feeling of confidence in the dive-bomber had therefore been engendered by the Stuka’s performance in Spain. No bad thing, and one which would serve the crews well in the opening months of the war that was to come. However, in one important respect the Ju 87 remained untested – its ability to survive in a completely hostile airspace.

Although the Ju 87 was a de facto ground-attack aircraft, the creation of dedicated ground-attack formations for service in World War II was centred largely on other aircraft. One of the key names in this work was the great Luftwaffe fighter pilot, ‘ace’ and commander Adolf Galland. After service in the Legion Condor, Galland had relinquished command of 3.J/88 late in May 1938, shortly before the Staffel converted to the Bf 109. The passionate fighter pilot had not managed to claim a single kill during his time in Spain. To rub salt into the wound his successor – one Werner Mölders – quickly made the most of the unit’s new Messerschmitts by downing a couple of I-15s. And these were just the first of the 14 victories which would see Mölders emerge as the Legion Condor’s highest scorer.

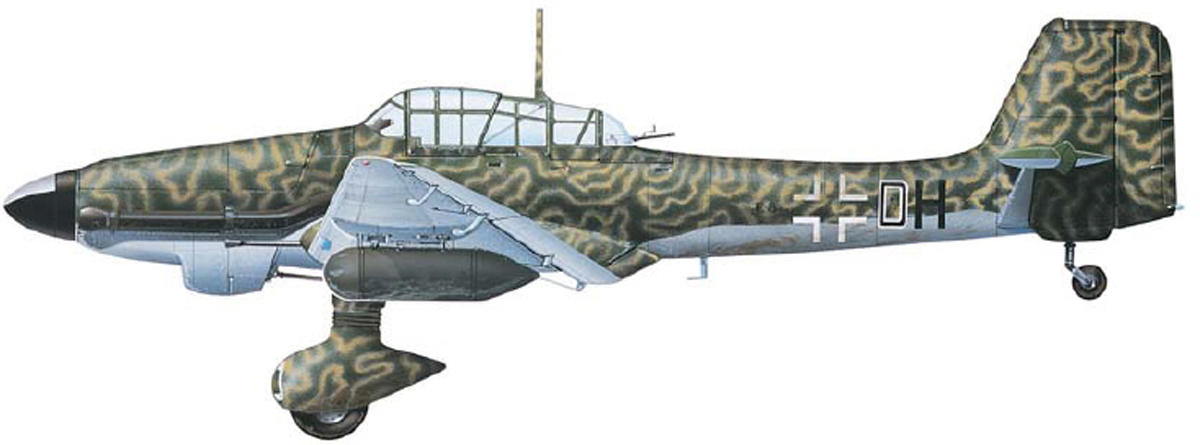

Ju 87G ‘S7+EN’ (Wk-Nr. 494231) of Feldwebel Josef Blümel, 10.(Pz)/SG 3, Wolmar, Latvia, September 1944. Appropriately displaying the Panzerjäger badge on its cowling, this was the machine Josef Blümel was flying when he claimed his 60th Soviet tank on 19 September 1944. On a second mission later that same morning, however, the Ju 87 was damaged by anti-aircraft MG fire and Blümel was forced to land behind enemy lines south of the Latvian capital, Riga. Both he and his radio operator were executed by Red Army troops. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

Galland hoped that a return to the Reich would also mean a return to fighters, but he was to be disappointed. With growing confidence Hitler had already marched his troops into the de-militarized zone of the Rhineland and annexed Austria – both actions specifically prohibited by the Treaty of Versailles. Now the Führer had his sights firmly set on the Sudeten territories of Czechoslovakia.

To add weight to his demands, Hitler ordered his ever-growing Luftwaffe to mount a strong aerial presence along the borders with the disputed territories. The Luftwaffe duly obliged by providing over 40 Gruppen, predominantly bomber, dive-bomber and fighter. Among the Stukagruppen included in this force was Hs 123-equipped III./StG 165, which was then the only unit of its kind not yet flying the Ju 87.

As an additional safeguard, should this show of strength prove insufficient and an actual armed invasion be required to wrest the Sudetenland from Czechoslovakia, it had further been decided that a ground-attack force – similar to, but much larger than, the one that had recently been so successful in Spain – would be the ideal weapon to open up a gap in the Czechs’ frontier defences. And who better to help organize such a force than the man who had just spent ten months with the Legion Condor perfecting the very tactics which would be needed to do the job?

His post-tour leave suddenly cancelled, Adolf Galland thus found himself behind a desk in the new RLM building in Berlin, involved in the creation of five ad hoc ground-attack Gruppen. Despite the confusion and haste – ‘of course, everything was wanted by the day before yesterday at the latest’ – the five new units, designated Fliegergruppen, were activated in time to participate in a large-scale exercise before taking up station along the Reich’s borders with the Sudetenland.

Three of the Gruppen were assigned to Lw.Gr.Kdo. 1, the command deployed in Silesia, Saxony and Thüringia to the north and north-west of Czechoslovakia. Fliegergruppen 10 and 50, based at Brieg and Grottkau respectively, were by now both equipped with ex-school Hs 123s, while Fliegergruppe 20, at Breslau, had to make do with the antiquated He 45, long ago rejected as a light bomber, but still soldiering on in the reconnaissance role. The other two units, Fliegergruppen 30 and 40, came under the control of Lw.Gr.Kdo. 3 in Bavaria and Austria to the south-west and south of Czechoslovakia. Fliegergruppe 30’s Hs 123s were stationed at Straubing, while the outdated He 45s of Fliegergruppe 40 took up residence at Regensburg.

By the latter half of September 1938, with his ground and air forces fully assembled, Hitler’s ‘show of strength’ was in place. In the event, he was not required to unleash that strength. The British and French governments were united in their apparent desire to follow the path of appeasement at all costs. On 30 September they co-signed the Munich Agreement, ceding the Sudeten territories of Czechoslovakia to the Greater German Reich. Twenty-four hours later Hitler’s forces marched virtually unopposed across the now defunct frontier.

Most of the Luftwaffe units gathered for Fall Grün (Case ‘Green’, as the Sudetenland operation had been code-named) were quickly dispersed back to their home bases. Of the five ground-attack Gruppen, only one, Hauptmann Siegfried von Eschwege’s Fliegergruppe 30, was transferred into the newly occupied zone. Its stay at Marienbad was to be brief, however, and on 22 October it rejoined Fliegergruppe 40 at Fassberg, in northern Germany.

Although their operational careers under the guise of Fliegergruppen had been short-lived, the effort expanded in creating these five units did not go to waste. Three were re-equipped with the Ju 87 and redesignated as Stukagruppen, a fourth converted to Do 17s to become a Kampfgruppe, and the fifth – Fliegergruppe 10 – joined the ranks of the Lehrgeschwader in November 1938 to provide a nucleus for the sole Gruppe to be formed in furtherance of the science of ground attack. Some sources maintain that it was the He 45-equipped Fliegergruppe 20 which was selected for this role.

The Luftwaffe’s Lehrgeschwader were mixed-formation units tasked with the operational evaluation of new machines and/or the development of new tactics. Each Gruppe within a Lehrgeschwader was equipped with a different type of aircraft. Lehrgeschwader 2, for example, consisted of a fighter Gruppe, a reconnaissance Gruppe and Fliegergruppe 10’s Hs 123s. As such, they alone represented the Luftwaffe’s entire dedicated ground-attack strength during the final ten-month countdown to war.

After helping to establish the five Fliegergruppen at the time of the Munich Crisis, Galland had finally been permitted to return to his true love – fighters. However, his tenure of office as Staffelkapitän of 1./JG 433 (which became 1./JG 52 on 1 May 1939) was to last exactly nine months. His knowledge of, and experience in, ground-attack operations had not been forgotten by the upper hierarchy and on 1 August 1939, as the war clouds gathered over Europe, he was posted to II.(Schl)/LG 2. It now formed part of Generalmajor von Richthofen’s Fliegerführer z.b.V. This was the ‘special duties’ command – consisting mainly of Ju 87 Stukas – which was to provide the aerial component of the world’s first Blitzkrieg operation: the smashing of a narrow breach in Poland’s defences by 10. Armee and its subsequent all-out drive, spearheaded by 1. and 4. Panzer Divisionen, north-eastwards to the enemy’s capital, Warsaw.

Ju 87B dive-bombers sit in winter snows. If all else failed, the last resort for coaxing a frozen engine back into life was to light a fire underneath it.

However, von Richthofen, who in Spain – like some field commander of old – had often watched his troops in action from the vantage point of a nearby hilltop, was aware not only of the Hs 123’s capabilities, but also of its limitations: ‘By the time Spielvogel and his old crates finally reach the front from Alt-Siedel,’ he complained, ‘they will already have used up nearly half their fuel.’ He therefore issued instructions that a forward landing ground be made available for Major Werner Spielvogel’s ‘crates’ close to the Polish border.

It was no accident that the Ju 87 was selected to carry out the very first operation of World War II, which was initiated some 20 minutes before the official outbreak of hostilities! Given the nature of the objective, no other choice was possible.

The easternmost province of the Reich, East Prussia, was cut off from Germany proper by the Polish Corridor. This hotly disputed strip of territory, which afforded the landlocked Poles access to the Baltic Sea, was another product of the Treaty of Versailles, and a contributory factor in Hitler’s decision to attack Poland. Across its neck ran a single railway which connected the province to Berlin. This track would be a vital lifeline between the two in time of war. Its weakest link was the bridge at Dirschau (Tczew), where it spanned the River Vistula. Both the Germans and Poles were aware of this, and the latter had prepared the bridge for demolition should they be attacked.

The target for the first bombing raid of the war was, therefore, not the bridge itself, but the demolition ignition points situated in blockhouses at nearby Dirschau station, plus the cables which ran out along the railway embankment on to the bridge. The objective was to prevent the structure from being destroyed before it could be seized by German ground troops being transported into Poland by armoured train. It was a job that only the Stuka could do. Wearing civilian clothes, pilots of I./StG 1 – the unit ordered to carry out the attack – had undertaken their own first-hand reconnaissance by travelling back and forth several times in the sealed trains (inevitably known as ‘corridor trains’) in which Germans were allowed to traverse the 100km stretch of line that connected East Prussia with the Fatherland.

At exactly 0426hrs on 1 September 1939 a Kette (three-aircraft formation) of Ju 87s of 3./StG 1, led by Staffelkapitän Oberleutnant Bruno Dilley, lifted off from their forward base in East Prussia for the eight-minute flight to the target. Despite the all-pervading ground-mist that blanketed the area, the trio of Stukas, each loaded with one 250kg bomb, plus four smaller 50kg weapons slung in pairs under each wing, soon spotted the unmistakable iron lattice-work of the bridge looming ahead of them. Flying at a height of just 10m above the flat Vistula plain, the three pilots climbed as one before separating to plant their bombs unerringly on the station blockhouses, severing the finger-thick cables. Despite the successful completion of the mission, it was all to no avail. The armoured train was delayed, and the Poles managed to destroy the bridge before German ground troops could reach it. The first bombing raid of the war had been a carefully planned – albeit ultimately abortive – operation.

Also in the pre-dawn darkness of 1 September 1939, the 39 pilots of II.(Schl)/LG 2 found themselves running up their engines on a small field outside the township of Alt-Rosenberg, less than 15km behind the arm of the River Warthe which marked Germany’s frontier with Poland in this region. Despite the swathes of ground mist still clinging to the damp grass of the meadow, all got off safely. From his forward HQ immediately to the south of the border crossing point at Grunsruh, von Richthofen could hear the approaching Hs 123s. Their shapes were just visible as they circled above the river, their engines ‘droning angrily like a swarm of disturbed hornets’.

At 0445hrs precisely, Hauptmann Weiss, Spielvogel’s senior Staffelkapitän, led the Henschels in to the attack. On the far bank of the river he quickly spotted the Gruppe’s objectives – Polish Army installations, identified by Intelligence as being occupied by forward elements of the enemy’s 13th Division, in and around the village of Przystain.

Every one of Weiss’s 4. Staffel pilots placed his load of four 50kg explosive-incendiary bombs with precision. Hard on their heels, Galland’s 5.(Schl)/LG 2 did the same. By the time 6. Staffel commenced its run, the enemy positions were shrouded in smoke and flames. Despite being taken by surprise, the Polish troops responded with light AA and small-arms fire. However, this opposition was soon suppressed as the Henschels, splitting up into individual Ketten (three-aircraft formations), then carried out a series of strafing runs, hedge-hopping over and around trees and other obstacles, and raking the Poles with machine gun fire.

Generalmajor von Richthofen watched the entire proceedings from the near bank of the Lisswarthe. What he was witnessing in the dawn light of 1 September 1939 was the first ground-attack operation of World War II to be mounted by the Luftwaffe in direct support of an advancing army. And it was a complete success. At the end of that momentous day the OKW issued a communiqué summarizing events. It included the phrase, ‘… in addition, several Schlachtgeschwader provided effective support for the army’s advance’.

The successful attack on Przystain on the opening morning of hostilities set the pattern for the week ahead. Over the next seven days Major Spielvogel’s II.(Schl)/LG 2 continued to blast a path for 10. Armee’s Panzers as they drove hard for Warsaw. Whenever an armoured or motorized infantry unit was brought to a temporary halt by strong local enemy resistance, the call went out for the ‘one-two-threes’ to clear the obstacle. In the process, the Henschels earned a new nickname for themselves. The Trabajaderos (‘labourers’) of Spain became the Schlächter (‘butchers’) of Poland. It was a brave – and rare – enemy column that could withstand the sight, and sound, of a dozen or more Hs 123s roaring along a road just 10m above their heads. Men and horses bolted in panic. Drivers and crews leaped from their vehicles to seek what cover they could. Had they but known it, the more racket the Henschels were making, the safer those on the ground actually were, for at those revs, or so it has been said, the pilots were unable to fire their machine guns for fear of shooting their own propellers off!

However, there were also plenty of opportunities to employ more lethal measures, strafing and dropping a whole arsenal of 50kg high-explosive and incendiary bombs, as the Henschel pilots kept up the pressure, mounting one sortie after the other as long as daylight lasted. The Stuka crews were doing the same, while overhead flew the Heinkels and Dorniers of the Kampfgeschwader. Even the Messerschmitt fighter and Zerstörer Gruppen were being called upon to carry out low-level ground-strafing attacks. Ground-attack aircraft thus played a central role in the defeat of Polish forces in the autumn of 1939.

With the cessation of hostilities in Poland, II.(Schl)/LG 2 returned to Brunswick, in Germany, for rest and refit. The winter of 1939–40, one of the most severe in living memory, was spent quietly. It was not until 1 February 1940 that two of Hauptmann Weiss’s Staffeln were moved up to München-Gladbach, just 24km from the Dutch border.

The Gruppe still formed part of Generalmajor von Richthofen’s ‘special duties’ command which, by this time, had been raised to the official status of a Fliegerkorps. Anticipating that the aerial opposition to be faced in the forthcoming attack in the West would be much stronger than that put up by the gallant, but outclassed, Poles, the new VIII. Fliegerkorps was assigned its own protective fighter force of Bf 109s. A Do 17-equipped Kampfgeschwader was also temporarily attached to increase the range of the corps’ striking power.

Again, Hitler’s ground-attack aircraft were in the vanguard of operations in the West. They supported the pioneering Luftwaffe airborne assault on the Belgian fortress of Eben Emael on 10 May 1940, then provided air cover for the Panzer assault through Belgium. By day’s end the Gruppe had flown some eight to ten ground-support missions, as indeed had most of VIII. Fliegerkorps’ units – even its attached reconnaissance Staffel had been armed with 50kg bombs so that it could engage ‘targets of opportunity’.

By that time, too, the Panzer and motorized infantry divisions of 6. Armee were starting to pour in an uninterrupted stream through the town of Maastricht and out along the two exit roads leading westwards, across the Vroenhoven and Veldwezelt bridges, into Belgium. Over the next few days Allied bombers made many desperate, near suicidal, attacks on the ‘Maastricht bridges’ in repeated attempts to stop this flow of traffic.

With the all-important bridges now securely ringed by flak batteries and covered by standing fighter patrols, Weiss’s pilots were able to roam slightly further afield on day two of the campaign. This led to their first recorded brush with the expected ‘strong’ enemy fighter opposition. It came in the form of an RAF Hurricane of No. 607 Sqn, which got in ‘four or five bursts’ at one of 5. Staffel’s machines as they were busy bombing Belgian positions along the River Meuse. Although claimed as a kill, the Henschel returned to base only slightly damaged.

These trainee crews discuss anti-tank techniques with their Hauptmann instructor.

1: A typical approach commences from 4,500m. As the target is acquired through the floor window, the range-timing clock is set. The engine is reduced to idling speed, air-intakes are closed and dive-brakes opened. The nose drops into an instantaneous 80º dive and the timing clock is started.

2: A Ju 87 tended to oscillate in the dive, but the pilot centres the target in the ‘Revi-16B’ reflector sight, holding it in the crosshairs. A buzzer sounds at 2,100m (c. 30 seconds into the dive), and the pilot starts the release and recovery timer.

3: The aircraft continues to plummet at c. 560km/h, largely driven by gravity. At 1,000m, the Einhängung cradle unlocks to swing the bomb away from the fuselage and clear of the propeller. The bomb slips free as the auto-recovery system commences simultaneously. The crewmen push their heads back against padded restraints to prevent their chins being forced painfully into their chests.

4: Auto-recovery pulls the aircraft out of the dive so steeply that crewmembers usually black out under forces of 3–4G. The bomb continues its line of descent towards the target (approximately 15 seconds to impact). The pilot resumes consciousness and control of aircraft. (Adam Hook © Osprey Publishing)

But all this intense early activity on the northern flank of the offensive – spectacularly successful though it was proving to be – was, in reality, a gigantic feint deliberately designed to lure the Allied ground forces up into Belgium in response. The main thrust, to be delivered by the five Panzer divisions of 12. Armee, would then be launched through France out of the Ardennes hills to the south, and would again be capably supported by ground-attack formations, which fought nearly all the way to the French coast.

By early June the campaign in France was virtually over and so, it seemed, was the operational career of the Hs 123. When von Richthofen’s Stukas began transferring up to Normandy the following week as part of the preparations for taking the war to England’s shores, II.(Schl)/LG 2 did not accompany them. The Henschels had proved themselves rugged and willing workhorses, able to operate from the most primitive of grass fields and capable of absorbing tremendous punishment. They had also provided invaluable support to ground troops at numerous water barriers.

However. the next hurdle facing VIII. Fliegerkorps was no Polish stream, Belgian canal or French river. It was the 112km width of the English Channel separating Cherbourg from the Dorset coast and it was an obstacle the short-legged ‘one-two-threes’ simply could not overcome.

Otto Weiss, who was promoted to Major on 1 July, therefore led his Gruppe back to Brunswick-Waggum for re-equipment. It was not just the Hs 123, the ‘interim dive-bomber’ turned ground-attack aircraft, which was facing retirement. The entire Schlacht arm was in imminent danger of dissolution. The elderly biplane’s intended successor, the Hs 129, a heavily armoured, twin-engined machine designed from the outset for the ground-attack role, had first flown more than a year earlier. However, it had proved a major disappointment.

Plans had already been mooted to convert II.(Schl)/LG 2 into a bona fide dive-bomber unit equipped with the Ju 87. Many felt that the dedicated ground-attack machine, despite the success of the strafing and bombing aircraft above the trenches of World War I, had no place in a modern war of movement. The new ‘wonder weapon’ of the Blitzkrieg era was the Ju 87 Stuka, which had already demonstrated its abilities – not only by carrying out pinpoint dive-bombing attacks, but also by flying low-level strafing missions. And these latter, to all intents and purposes, were ground-attack operations.

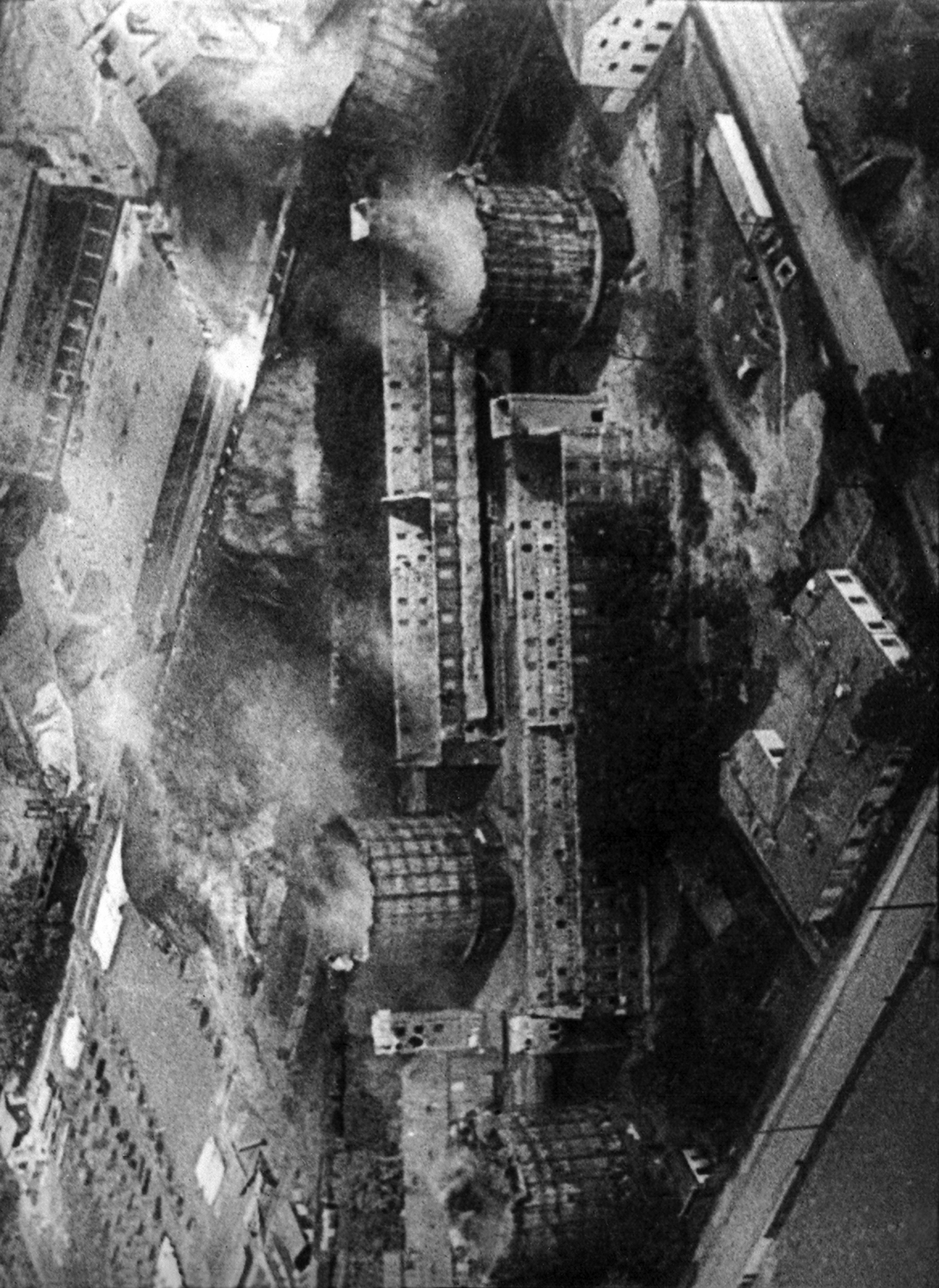

Warsaw burns following an attack by Stukas in 1939. The Stuka was capable of precision ground-attack operations, but it was also used in a more indiscriminate capacity, as seen over cities such as Leningrad and Stalingrad on the Eastern Front.

Major Oskar Dinort, Gruppenkommandeur of I./StG 2 ‘Immelmann’, recalls one of the earliest aerial actions in Poland shortly after midday on 1 September 1939, when air reconnaissance brought back reports of large concentrations of Polish cavalry advancing on Wielun and threatening the northern flank of the German XVL Armeekorps:

‘We moved up into Poland. Our new base was some seven kilometres outside the town of Tschensrochau (Czesrochowa). We arrived about midday and the base personnel immediately set about erecting tents and organizing defensive positions. We were, after all, on enemy soil and the woods bordering the field to the north-east were reportedly full of Polish stragglers …

‘… sure enough, hardly had darkness fallen before shots rang out from the edge of the woods. Our ground-staff replied with machine-guns and light flak. The whole field was eerily illuminated by flickering searchlight beams and red beads of tracer. The firing continued throughout the night, but died out shortly after 4 am when it started to rain. At last we aircrew could snatch some sleep.’

Dinort and his crews got all the rest they needed. The rain persisted, and they did not take off until 3 pm the next afternoon. Their targets were the bridges over the Vistula near the fort of Modlin, to the north of Warsaw:

‘We climbed through the grey clouds and broke out into clearer air at some 1200 metres. Below us the ragged valleys of cumuli, above us a leaden, sunless sky.

‘Course north-east. Visibility was still not good. The windscreen streaked with more rain. Only the occasional glimpse of the ground and brief sighting of the Vistula through a break in the clouds to keep us on track. At last I saw the fort below us. It lay in the brown landscape, huge, grey and pointed like some burned-out star. And there too the Vistula bridges. Tiny lighter strips against the dark bed of the river: our target.

‘The moment has come. Wing over into the dive! The machine drops like a stone. The altitude unwinds – down 200 metres, 300, 500. The instruments can hardly keep pace with the rate of descent. Then the red veil in front of the eyes that every Stuka pilot knows. 1400 metres from the ground … 1200 metres … press the release. The bomb falls away into the depths below.

‘I recover and take the usual evasive measures. Linking away, I look back. Behind me the Stabskette are in the middle of their dive, the first Staffel right on their tails, dark shadows against the lightening sky. Their aim is good … one bomb hits the centre of the target.’

In the event, Major Weiss’s Gruppe was re-equipped not with Ju 87s, but with Bf 109 fighter-bombers. The reason for the change of policy is not known. The bursting of the Stuka bubble over southern England by RAF Fighter Command was still some weeks away. However, the conversion to Messerschmitts may well have been a lucky escape for II.(Schl)/LG 2.

The advent of the fighter-bomber was a further muddying of the waters as far as the ground-attack concept was concerned. Both Bf 109 fighters and Bf 110 Zerstörer had also flown ground-strafing sorties in Poland and the west. Also, an experimental Gruppe equipped with the two types was currently undergoing training prior to commencing cross-Channel fighter-bomber operations.

II.(Schl)/LG 2’s own re-training for the fighter-bomber role, which was completed at Böblingen in southern Germany, lasted well into August. It thus missed the opening rounds of the Battle of Britain.

Over Poland in 1939, then Scandinavia, France and the Low Countries in 1940, the Stuka seemed to prove both the theory and practice of the dive-bombing ground-attack mission. Precision strikes ahead of the armoured spearheads had a terrifying effect on Allied positions and troop movements, and helped to pave the way for the armoured advance. Ju 87s delivered some of the last aerial attacks on the British evacuation from Dunkirk, on one day assisting in the sinking of 31 Allied vessels off the French coastline. Yet as the Introduction to this book indicated, everything changed during the summer of 1940, with the Luftwaffe’s attempt to subdue the RAF in the Battle of Britain.

The Battle of Britain actually began with the Kanalkampf (Channel Battle) attempts by Ju 87s, Do 17s and other aircraft to interdict British shipping in the Channel. One of the first reported encounters between Ju 87s and British shipping in this latest phase of the Stuka’s operational career had been an ineffectual dive-bombing attack (believed to have been mounted by III./StG 51) on deep-sea convoy ‘Jumbo’, which was attacked whilst approaching Plymouth early on the afternoon of 1 July. Three Hurricane Is of No. 213 Sqn were scrambled from Exeter to engage the Stukas, but by the time they had arrived over the convoy the raiders had long since departed.

Three days later III./StG 51 staged a maximum-effort raid on Portland harbour that resulted in probably the highest military loss of life ever inflicted by a single air attack on the British Isles. Led by their new Kommandeur, Hauptmann Anton Keil, some 33 Stukas dived out of the morning mist, which hung over the naval base, totally unannounced. They concentrated their attacks on the largest vessel in the harbour, the auxiliary AA ship HMS Foylebank, and within eight minutes 22 bombs had struck the ship, killing 176 of her crew.

With no RAF fighters in the vicinity, the Gruppe escaped back to Cherbourg all but unscathed, having also set fire to an oil tanker moored in Weymouth Bay with a direct hit from a 500kg bomb prior to making good their escape – the vessel burned for 24 hours before the flames could be brought under control. The only loss inflicted upon the Ju 87s was one machine brought down over the target area, its wing blown off by a direct hit from one of the Foylebank’s 4in. AA guns – both Leutnant Schwarz and his gunner were killed in the subsequent crash. A second Stuka landed back at Cherbourg having suffered minor flak damage.

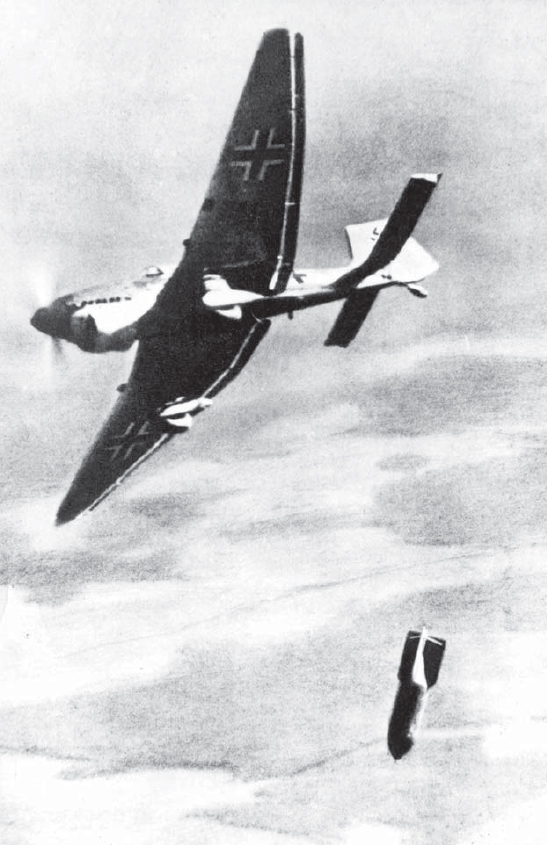

A Ju 87 Stuka releases its bomb as it pulls out of its near-vertical dive. This was actually the most dangerous moment of an attack for the Stuka, as its speed and manoeuvrability drained away in the climb.

The Stukas continued to inflict a heavy punishment on Allied shipping around the British coastline for the rest of the month, with the British fighters often arriving too late to inflict casualties on the dive-bombers. The weather deteriorated as July drew to a close, but the Stukagruppen had already performed to perfection the initial task required of them in the run-up to the planned invasion of England. By ‘plugging’ the Channel at either end, and neutralizing the Royal Navy’s south coast destroyer flotillas (which had lost a dozen vessels since mid-May, plus many others withdrawn from the area for essential repairs), they had secured the cross-Channel sea lanes for the invasion fleet, which was even now being assembled in northern European ports.

Next would come phases two and three of their part in the conquest of Great Britain. In August – repeating the tactics of Poland and France – they would take out RAF Fighter Command’s forward airfields in a series of precision attacks in preparation for the landings. And in September, once the German Army was safely ashore, they would resume their classic role of ‘flying artillery’ as the ground-troops pushed northwards into the heart of England. The relative ease with which they had accomplished phase one (at a cost of only some dozen aircraft lost or written off) had given no indication of the storm that was about to break over them.

The 13th of August 1940 – Adlertag – was the opening round of the Luftwaffe’s main air assault on the British Isles. For the protagonists, their ‘big day’ did not get off to a good start for adverse weather conditions in the early morning led to last-minute postponement orders being transmitted. However, not all units received them, and in the resulting confusion some bombers flew missions devoid of fighter cover, while other fighters dutifully flew to assigned target areas without the bombers they were meant to protect!

By the afternoon, however, the weather had improved sufficiently to allow the Stukagruppen to launch the second phase of their three-part role in the overall invasion plan – a series of pinpoint attacks intended to neutralize Fighter Command’s forward fields. They struck along both flanks of the designated assault zone. In the east Luftflotte 2 despatched II./StG I against Rochester and IV.(St)/LG 1 against Detling. The former failed to locate their target, but Hauptmann von Brauchitsch’s 40 Ju 87s caused severe damage at Detling, killing 67 (including the station commander Group Captain Edward Davis), demolishing the hangars and totally destroying 22 aircraft. Retiring without loss, IV.(St)/LG 1 landed back at Tramecourt with justifiable feelings of a job well done. It was German intelligence that was at fault – Detling was not a Fighter Command airfield. Indeed, the only aircraft permanently based there were Ansons of No. 500 ‘County of Kent’ Sqn, which had been seconded to Coastal Command since early 1939. One of the unit’s armourers provided this candid description of the oncoming raid as seen from his squadron dispersal:

The B Flight night-duty ground crew finished their evening meal and waited in and around the Dennis lorry which would take them to the Anson aircraft, parked in fields alongside the Yelsted road at the northeast corner of Detling aerodrome.

Faintly, in the distance, Maidstone’s air-raid shelter sirens were heard, and then the drone of aircraft. These aircraft could be seen approaching the airfield from about two miles [3.2km] away to the south-east at a height of about 5,000ft [1,524m]. The formation was much larger than had been seen in the area before – so much so that it prompted one of the squadron armourers, Bill Yates, to announce that he ‘didn’t know we had so many’. This remark almost qualified for ‘Famous last words’ as Yates clambered to the Dennis’ canvas top and began a count of the aircraft. He had passed the 30 mark when the leading machine dipped its port wing in a diving turn, and became without any shadow of a doubt a Stuka.

To the west, units of VIII. Fliegerkorps suffered diversities of fortune. Elements of StG 77 searched in vain for Warmwell before dropping their bombs at random over the Dorset countryside and returning to their Caen airfields unmolested. Despite being bereft of fighter cover (their 30 Bf 109 escorts from II./JG 53 had been obliged to turn back through a shortage of fuel), Hauptmann Walter Enneccerus’ 27 Ju 87Rs of II./StG 2 crossed the coast near Lyme Regis en route for Middle Wallop, but they never made it. Intercepted by 13 Spitfire Is of No. 609 Sqn, they lost five of their number in a one-sided duel over the coast, and a sixth which crashed into the Channel during the return flight – the RAF claimed to have destroyed or damaged 14 Ju 87s and Bf 109s and suffered no losses. This decimation of the Stukas had been witnessed from the Portland cliffs by Prime Minister Winston Churchill and a clutch of senior Army generals. One of the pilots to claim a Ju 87 destroyed, and a second dive-bomber damaged, was leading No. 609 Sqn ace, Flying Officer John Dundas:

Thirteen Spitfires left Warmwell for a memorable Tea-time party over Lyme Bay, and an unlucky day for the species Ju 87, of which no less than 14 suffered destruction or damage in a record squadron ‘bag’, which also included five of the escorting Me’s. The formation, consisting of about 40 dive-bombers in four-vic formation, with about as many Me 110s and 109s stepped-up above them, was surprised by 609’s down-sun attack.

The four-minute massacre off the Dorset coast was the beginning of a terrible period for the Stukas. Their loss rates spiralled upwards – between 8 and 18 August some 20 per cent of the entire Stuka force were destroyed over Britain, and 33 other machines destroyed. The dive-bombers did not have the manoeuvrability or the power to survive on their own in a dogfight against the superior British fighters. Their very dive attack profile also left them ideally placed for fighter interception as they crawled out of the dive and attempted to gain altitude. By 18 August, therefore, the Stuka had been effectively pulled out of operational service over Britain, and even the aircraft’s staunchest advocates were having to concede that the Stuka was not operable as a strategic weapon if pitted against a determined defence.

Ju 87G ‘Black Chevron and Bars’ (Wk-Nr. 494193) of Oberst Hans-Ulrich Rudel, Geschwaderkommodore SG 2, Niemes-South, Czechoslovakia, May 1945. Although he had a Fw 190D-9 at his disposal, Hans-Ulrich Rudel remained true to the Ju 87 Stuka until the very end. And it was in the Stuka that Rudel chose to fly his last mission on 8 May 1945, and then lead the seven aircraft of his HQ flight (three Ju 87s and four Fw 190 escorts) to Kitzingen and surrender to US forces. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

By contrast, the results being achieved by the experimental Erprobungsgruppe 210 since the start of their low-level precision fighter-bomber attacks on southern England in mid-July were more than encouraging. The success of Erpr.Gr. 210’s operations prompted an exasperated Göring to order that one-third of his entire Channel-based fighter force be similarly converted to carry bombs.

In the weeks and months ahead, throughout the winter – weather permitting – and into the early spring of 1941, II.(Schl)/LG 2 kept up its sporadic attacks on southern England. Flying from St Omer and Calais-Marck, the unit’s targets included RAF airfields, oil refineries, railways, docks and coastal shipping. Although usually accompanied by a fighter escort – often provided by JG 27, the unit which had been assigned to protect its Henschels in France – these operations resulted in a dozen or more combat casualties. Fortunately, some two-thirds of the pilots survived to become prisoners of war.

Of course, none of the operations flown by II.(Schl)/LG 2 during its six-month campaign against England were Schlacht missions in the truest sense of the word – i.e. ground-attack sorties flown in direct support of the Army in the field. Yet, oddly, the (Schl) abbreviation continued to be used in the unit title. Perhaps Weiss’s pilots were to have reverted to their original role once the German Army had set foot on England’s shores?

In the meantime, the Gruppe had retained both a sense of individuality, and a link with the past, by applying a unique set of markings to its Bf 109s. Each machine was identified by a letter, rather than a fighter-style numeral, and each sported a large black equilateral triangle ahead of its fuselage cross. Such triangles had first been worn by the aircraft of the Fliegergruppen at the time of the Munich crisis. Their re-adoption may well have been at the instigation of Major Weiss himself, who had served as a Staffelkapitän in Werner Spielvogel’s Fliegergruppe 40 during that period.

Between September 1940 and March 1941 these triangles – a few litres of black paint at most – were the only outward sign of what was now, in effect, an all but extinct ground-attack force. However, the triangle would survive to become recognized as the official symbol of the Schlacht arm, for a resurrection was about to take place. Less than a fortnight after its last Bf 109 had been lost over England (or, to be more precise, had been shot into the Channel off Dungeness) on 15 March 1941, II.(Schl)/LG 2 was given something far more tangible than mere markings to show that it was still very much in the ground-attack business – a new intake of old Hs 123s.

By the first week in January 1941, II.(Schl)/LG 2’s strength at St Omer/Arques had sunk to just 11 serviceable Bf 109s. This was probably the lowest point in the fortunes of the Luftwaffe’s ground-attack arm at any time in the war. However, a change of strategic policy by the Führer heralded a reversal in those fortunes and marked the beginning of the Schlacht force’s emergence and expansion into one of the most important fighting components of the Wehrmacht.

The proposed invasion of England, shelved the previous autumn, was now postponed indefinitely. Hitler’s attention was focused instead on Nazi Germany’s traditional enemy, Communist Russia. Plans for an attack on the Soviet Union were already well advanced when a popular uprising by the people of Yugoslavia against their pro-Axis government forced the Führer into an unplanned, and unsought, campaign to stabilize his south-eastern borders.

Among the Luftwaffe units hastily assembled for a combined assault on Yugoslavia and Greece (the latter country currently locked in conflict with, and thoroughly trouncing, Germany’s ally Italy) was II.(Schl)/LG 2. The Gruppe’s paucity in numbers was soon made good. By the end of March 1941 they were fielding 30+ Bf 109s. However, as the coming action in the Balkans was to be a repeat of the previous year’s Blitzkrieg campaigns – an all-out offensive against the enemy’s armies in the field – the Messerschmitts were divided between just two of the Gruppe’s component Staffeln. The third was re-equipped with that trusty veteran of ground-attack operations, the Henschel Hs 123, now brought out of retirement for a second time.

In addition, a completely new Staffel, 10.(Schl)/LG 2, was formed and likewise equipped with ‘one-two-threes’. The two Staffeln’s total complement of 32 Henschels, taken together with the others’ Bf 109s, meant the Gruppe was again numerically the strongest of any being committed to the coming campaign. By the first week of April, operating once more as part of General der Flieger von Richthofen’s VIII. Fliegerkorps, II.(Schl)/LG 2 had transferred down into Bulgaria. The main body of the Gruppe was based at Sofia-Vrazdebna, close to the Bulgarian capital, while 10. Staffel shared nearby Krainici with elements of StG 2.

Operation Marita, launched in the early hours of 6 April 1941, began in true Blitzkrieg style with heavy raids on the enemy’s airfields and frontier defences. More accustomed perhaps to the lengthy approach flights which had preceded their recent cross-Channel fighter-bomber attacks on southern England, some of the Gruppe’s Bf 109 pilots seem to have been caught off guard by the immediacy and ferocity of tactical ground-support operations. At least three of their number crashed on returning to base, although whether this was a direct result of previous damage from ground fire has not been established. The Gruppe’s Bf 109s and Hs 123s were soon proving their worth in true Schlacht style, clearing a path for their own advancing forces by bombing and machine-gunning any reported pockets of opposition into submission or retreat. The Balkans were in German hands by the end of May 1941, by which point the Schlacht forces were readying themselves for a far greater adventure.

On the eve of the invasion of the Soviet Union II.(Schl)/LG 2 was based at Praschnitz (Praszniki) in the far north of German-occupied Poland, just below the Lithuanian border. Its strength comprised 38 Bf 109Es, all but one of which were serviceable, plus 22 Hs 123s (17 serviceable). The Henschels, it appears, were now all operated by the attached and enlarged 10. Staffel.

The Gruppe was still part of General von Richthofen’s close-support VIII. Fliegerkorps, the bulk of whose units had only recently arrived in the area following their successful participation in the Cretan campaign. Von Richthofen’s command was also, itself, one of the two corps which together provided the striking power of Luftflotte 2, the air fleet tasked with supporting land operations on the central sector of the coming Eastern Front campaign.

VIII. Fliegerkorps’ specific responsibility was the aerial support of the four armoured and three mechanized divisions of Panzergruppe 3, whose orders were to smash all opposition in the border areas of Soviet-occupied Poland and White Russia, before advancing as quickly as possible on Smolensk, ‘the last great fortress before the Soviet capital, Moscow’.

Despite its immense scale – involving three-and-a-half million German troops and their allies assaulting a front stretching some 3,000km from the Baltic to the Black Sea – Operation Barbarossa relied on the same basic Blitzkrieg formula as before. That meant, first and foremost, neutralization of the enemy’s air power. II.(Schl)/LG 2’s pilots played an important part in the savage and sustained strafing attacks on the 66 Soviet frontier airfields which marked the opening day of the invasion, which inflicted staggering Soviet losses, including 1,489 aircraft destroyed on the ground. So astonishing were these claims that the Luftwaffe High Command at first refused to accept them, only doing so after subsequent investigation on the ground had confirmed their accuracy.

Despite the enormity of its losses, the Soviet Air Force still managed to mount retaliatory bombing raids, but these were left to the Jagdgruppen to deal with as II.(Schl)/LG 2 now began to concentrate on its primary task – the support of the German armoured spearheads. Over the summer and autumn months of 1941, the ground-attack aircraft were shifted between various sectors, in each place exacting a heavy toll on Soviet troops, vehicles and armour. The original plans for Barbarossa had envisaged the capture of Moscow well before the onset of winter, but the enforced delay in its launch, brought about by the intervening campaigns in Yugoslavia and Greece, meant that German forces were still short of the Soviet capital when the first snows fell. They were ill-prepared and ill-equipped to face the appalling severity of the winter months that followed.

Bf 109E ‘White C’ of 4.(Schl)/LG 2, Moscow Front, Central Sector, November 1941. Depicted towards the close of II.(Schl)/LG 2’s 28-month long operational career, ‘White C’s’ standard Eastern Front finish and markings are all but obscured by a thick and irregular wash of temporary white winter paint. Oddly, this aircraft displays neither a unit badge nor the black ground-attack triangle. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

Hs 129B ‘White Chevron/Blue O’ of Hauptmann Bruno Meyer, Staffelkapitän 4.(Pz)/SchlG 2, El Adem, Libya, November 1942. The second specialized Hs 129 anti-tank Staffel to be formed, 4.(Pz)/SchlG 2 was destined from the outset for the North African theatre, as witnessed by the factory-applied camouflage finish of overall tan with disruptive green mottling. Bruno Meyer would later command the Hs 129-equipped IV.(Pz)/SG 9, and would survive the war having flown more than 500 ground-attack and anti-tank missions. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

Even the hardy Henschels found it almost impossible to continue operations from their base close to the River Ruza, some 80km to the west of Moscow. Blizzard conditions and temperatures plunging down to between 20 and 30 degrees below zero kept them firmly on the ground for most of the time. And when the Red Army renewed its counter-offensive around Moscow, using fresh Siberian divisions from the Far East, any last hopes of a quick conclusion to Barbarossa were finally dashed. German frontline troops had little option but to dig in and sit tight until the spring.

The end of 1941 also saw the end of II.(Schl)/LG 2. However, the Gruppe which had single-handedly kept the flag of the Schlacht arm flying – both figuratively and literally – for the past three years was being recalled to Germany not to disband, but to provide the nucleus for the first ever Schlachtgeschwader. Major Otto Weiss, who had commanded the Gruppe for almost its entire operational career, and who had been the first Schlacht pilot to receive the Knight’s Cross, now became the first to be awarded the Oak Leaves – on 31 December 1941 – before being appointed Geschwaderkommodore of the new unit early in January 1942.

A Luftwaffe Stuka pilot sits astride a destroyed Soviet gun emplacement at Sevastopol in the Crimea. In June 1942, Ju 87s subjected Sevastopol to near-continuous strikes, with the crews flying as many as eight sorties a day from their bases around Sarabuz.

II.(Schl)/LG 2’s destination in Germany was Werl, a pre-war fighter airfield to the east of Dortmund. It was here that Weiss established the Stab of Schlachtgeschwader 1, and II.(Schl)/LG 2 was redesignated to form the basis of his first Gruppe – I./SchlG 1. At nearby Lippstadt (likewise a fighter field of long standing) a second Gruppe, II./SchlG 1, was also activated mainly from scratch.

The mainstay of SchlG 1 was the Bf 109, but both Gruppen also received the Hs 123 and the heavily armed and armoured twin-engined Hs 129. It was to be used to equip two new Staffeln: 4.(Pz) and 8.(Pz)/SchlG 1. As the Pz (Panzer) abbreviation in their designation indicates, these two Staffeln were designed to operate as dedicated antitank units. Despite persistent powerplant problems, the Hs 129 would indeed develop into a potent tank-killer as subsequent models were fitted with ever more specialized weaponry, including large-calibre ventral anti-tank cannon and armour-penetrating hollow-charge bombs.

Operations against the Red Army in the spring of 1942 resumed where they had perforce been broken off late in 1941. However, the new year brought with it a change in the strategic direction of the campaign on the Eastern Front. The blockade of Leningrad in the north would continue. On the central sector, however, the German Army no longer had its sights set on capturing Moscow. The Führer had decreed that the primary objective of the 1942 offensive was instead to be the oilfields of the Caucasus in the far south.

SchlG 1 was therefore ordered to stage the 2,200km journey east south-east from the Ruhr to the Crimea. Unseasonably bad weather en route delayed its arrival, but on 6 May the unit paraded on the airfield of Grammatikovo for inspection by General der Flieger von Richthofen. Von Richthofen’s command was part of Luftflotte 4, the Air Fleet responsible for all operations on the southern sector.

Grammatikovo was situated at the base of the Kerch Peninsula. This easternmost part of the Crimea had been occupied by the Germans late in 1941, only to be retaken by the Red Army in a surprise midwinter counter-offensive. Now it had to be captured a second time.

For most of the younger pilots of II./SchlG 1 the two-week battle to clear the Kerch Peninsula was to be their introduction to Eastern Front operations. It was not an altogether reassuring experience. While VIII. Fliegerkorps’ Stukas bombarded the Soviet frontline positions, SchlG 1 was sent deep into the enemy’s rear to disrupt his lines of supply, both road and rail, and to attack any other reported signs of movement. However, the Red Army was no longer the disorganized, demoralized force it had been during the opening months of Barbarossa. Even the veterans of I. Gruppe were surprised at the way the Russian soldier now stood his ground, and at just how much fire – from cannon to small-arms – was thrown up at them. By the time the town of Kerch, on the tip of the peninsula, finally fell on 21 May, both Gruppen had sustained a number of losses from the heavy enemy ground fire.

On the surface, Fall Blau (Case Blue) appeared to be just the latest in a long line of classic Blitzkrieg campaigns. However, by this midway point in the war the cracks were beginning to show. There were clear signs that the Wehrmacht’s resources were being outstripped by the growing demands made upon it. For example, the pilots of SchlG 1 were now frequently required to fly their own pre-op reconnaissance sorties, as VIII. Fliegerkorps’ sole dedicated reconnaissance Staffel was often engaged on more pressing duties.

Nor did the Schlachtflieger enjoy the luxury of automatic fighter protection any more. This was something else they often had to provide for themselves. True, the occasional enemy aircraft had been claimed by ground-attack machines since the earliest days of the war, but these had usually been as a result of chance encounters. Now chance was turning into necessity as Red Air Force pilots began specifically to target the Geschwader’s bomb-carrying ground-attack Bf 109Es, the former regarding them as easier prey than the Luftwaffe’s Bf 109F fighters. In return, however, the Bf 109s often went hunting enemy aircraft themselves, the pilots giving free reign to their design to be fighter pilots as well.

Hs 129B-2 ‘Blue E’ of 4.(Pz)/SchlG 1, Mikoyanovka, Kursk Salient, July 1943. Based upon a photograph purportedly taken at the time of Operation Zitadelle (the great tank battle of Kursk), this profile of ‘Blue E’ offers evidence that the Hs 129, despite its unmistakable shape and form, was also toning down its markings. The black Schlacht triangle was long gone, and now the bright yellow nose panels – an ideal aiming point for Soviet anti-aircraft gunners – had, perhaps quite sensibly, been dispensed with too. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

The juxtaposition of duties, combining the ground-attack and the Zerstörer arms, was an indication of just how complex the growing assortment of Luftwaffe ground-support forces was becoming. Schlacht and Stuka units had long been engaged in essentially similar roles. To them had since been added two wartime creations – fighter-bomber (Jabo) and fast bomber (SKG) formations. Now twin-engined Zerstörer, whose original deployment as long-range fighter escorts had proved so disastrous during the Battle of Britain, were being categorized as ground-attack aircraft too.

Operationally, the ground-attack forces were playing out their roles against the backdrop of the Stalingrad disaster. With winter 1942/43 operations reduced to a minimum – between the months of November and March suitable flying weather could be expected on average on only one day in ten – the time was used instead finally to re-equip. It had long been acknowledged that the narrow-track undercarriage of the Bf 109 made it less than ideal for use on the Eastern Front’s uneven and unprepared grass airfields, particularly when encumbered with ventral and/or underwing racks and stores. The Focke-Wulf Fw 190, currently serving on the Channel front in the fighter-bomber role, offered the perfect replacement, its wide-set undercarriage legs being better able to cope with rough ground. The armoured ring in front of its air-cooled radial engine also provided increased protection against enemy ground fire (many a Bf 109 had met its end with a single bullet hole in its vulnerable coolant plumbing). Also, the Fw 190 was at its best at low to medium altitudes – the natural environment of the Schlachtflieger.

Commencing in late autumn, Major Hitschhold’s units were therefore rotated one Staffel at a time back to Deblin-Irena, in Poland, to convert onto Focke-Wulfs. It was a long drawn out process, which would not be fully completed until the end of April 1943. SchlG 1 did not reappear in full on Luftflotte 4’s order of battle until May 1943. Although still consisting of only two Gruppen (plus the specialized anti-tank Staffeln) upon its return to Eastern Front operations, the Geschwader represented a formidable fighting force well over 100 aircraft strong. Figures for mid-May indicate that Major Druschel’s enlarged Stab flight was made up of six Fw 190s, while 67 more Focke-Wulfs, plus 32 Hs 129s, were divided almost equally between his two component Gruppen.

A ground-attack version of the Fw 190. In addition to two 13mm machine guns and two 20mm cannon, the Fw 190D-9 variant also carried a single 500kg bomb on the fuselage centreline.

The Hs 123 may have been nearing the end of its service career, but there was still an urgent and growing need for an aircraft capable of combating the increasing numbers of Red Army tanks now beginning to dominate the Eastern Front battlefields. One answer seemed to lie in that other Henschel design, the Hs 129, which, despite its ongoing powerplant problems, had already claimed a considerable number of armoured kills. It was therefore proposed that, in addition to the established Pz. Staffeln, every Jagdgeschwader on the Eastern Front should have its own Hs 129 anti-tank Staffel. In the event, however, only one such unit – 10.(Pz)/JG 51 – was to be raised and see combat.

Another attempt to solve the problem had led to the activation of the Versuchskommando für Panzerbekämpfung (Experimental Command for Anti-Tank Warfare) at Rechlin late in 1942. This experimental unit was tasked with testing heavy anti-tank weaponry on other aircraft types. It was composed of four Staffeln – two of Ju 87s equipped with underwing 37mm BF 3,7 cannon, and one each of Bf 110s and Ju 88s, the former with a single BK 3,7 in a ventral fairing, and the latter carrying a massive 75mm PaK 40 cannon beneath the forward fuselage.

Field trials with the Bf 110s and Ju 88s, operating as Pz.J.Staffeln 110 and 92 respectively, proved unsatisfactory. The PaK 40-toting Ju 88s were particularly unwieldy, and one pilot still recalls the cannon’s recoil regularly blowing the nose and engine panels off his machine! Although the nose (and propeller blades) were subsequently strengthened, the inner nacelle panels of the armour-protected engines were thereafter always tied on with baling twine as an added precaution.

In contrast, the Ju 87’s 37mm underwing cannon were found to be highly effective against Soviet armour. In June 1943, the two experimental Staffeln, 1. and 2./Vers.Kdo.f.Pz.Bek., were therefore officially redesignated Panzerjägerstaffeln (anti-tank squadrons), one each being assigned to StGs 1 and 2 as specialized frontline tank-buster units.

The then Staffelkapitän of 1./StG 2, who had been given the opportunity to fly one of the test machines on operations, was quick to see the possibilities of the new weapon. The BK 3,7-equipped Ju 87G would become the aircraft of choice for Hans-Ulrich Rudel – the most famous and successful Stuka pilot of all – for the remainder of the war.

Many Kampfgeschwader set up so-called Eisenbahn (railway) Staffeln. Those flying He 111s usually just fitted their bombers with additional nose armament to carry out low-level strafing attacks on railway targets. The Ju 88-equipped units were slightly better off in being able to employ cannon-armed Ju 88C heavy fighters for their train-busting sorties. One of the greatest exponents of this latter art was 9.(Eis)/KG 3’s Leutnant Udo Cordes. Nicknamed the ‘Lok-Töter’ (‘Loco-killer’), in one short period during the spring of 1943 Cordes succeeded in destroying not just 41 locomotives, but 19 entire trains – including two carrying fuel and three transporting ammunition. After his unit was disbanded, Cordes spent the final weeks of hostilities flying Fw 190s with a Schlachtgruppe. Indeed it was the Fw 190 that was to be the dominant Schlacht aircraft, both in terms of numbers and performance, during the last two years of the war on the Eastern Front. It fulfilled all expectations, meeting every demand made upon it – and more. Under different circumstances it could well have had a significant influence on the course of the campaign. As it was, it was thrown into the maelstrom of Kursk in July 1943 – to great effect – but then began the final, gruelling retreat of German forces back to the Reich.

A Bf 110 undergoes maintenance to its nose-mounted machine guns. In the Bf 110E and 110G variants, armed with a powerful 30mm or 37mm cannon, the Luftwaffe had a potent anti-armour weapon that accounted for dozens of tanks in North Africa and on the Eastern Front in 1941–42.

By the winter of 1943, a new era was about to begin. Just as, on the ground, the German Army was attempting to stabilize and organize its forces along the Ostwall (East Wall), so, in the air, the Luftwaffe was finally beginning to recognize the value of its hitherto woefully neglected Schlacht arm. Some sort of order had to be created of the bewildering assortment of ground-support units – Stuka, Schlacht, Zerstörer, Schnellkampf, Jabo, Panzerjäger – which had been allowed to accumulate during the first four years of the war, but which, by this present stage of the conflict, were now all performing essentially the same tasks.

The initial step – the establishment of a unified command – had already been taken. On 1 September 1943, Oberstleutnant Dr Ernst Kupfer had been appointed as the Luftwaffe’s first General der Schlachtflieger. A Stuka pilot of long-standing, and latterly Geschwaderkommodore of StG 2 ‘Immelmann’, Dr Kupfer had recently led the Gefechtsverband Kupfer, a mixed-force battle group – including the Fw 190s and Hs 129s of SchlG 1 – which had come to the rescue of 9. Armee at Orel after the collapse of the Kursk offensive.

On 11 October Major Alfred Druschel had then relinquished command of SchlG 1 to assume the post of Inspizient der Tag-Schlachtfliegerverbände (Inspector of Day Ground-Attack Units) on Dr Kupfer’s staff.

Exactly one week after that, on 18 October 1943, the confusing mix of Luftwaffe ground-support units, together with their many, varied, and often complicated designations, was finally done away with. For on that date all were reorganized into Schlachtgeschwader – henceforth to be identified by the simplified abbreviation ‘SG’ – and incorporated into the framework of a new and greatly enlarged Schlacht arm.

Fiat CR.42 ‘Black 58’ of 3./NSGr 7, Agram (Zagreb), Croatia, July 1944. Another unit to be equipped with Italian machines (together with a miscellany of other types) was NSGr 7, which was operating on the other side of the Adriatic under the control of Fliegerführer Kroatien. Flying both nocturnal ground-attack missions and anti-partisan operations by day, 3. Staffel’s Fiats appear to have retained their original Regia Aeronautica camouflage, to which was added Luftwaffe theatre markings and national insignia (including an oversized swastika). (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

Me 262A-1a/U4 (Wk-Nr 111899) of Major Wilhelm Herget, JV 44, Munich-Riem, April 1945. Formerly a Messerschmitt works test vehicle based at Lechfeld, this is the Me 262 armed with the 50mm Mauser MK 214A nose cannon which ‘Willi’ Herget brought with him to JV 44 in January 1945. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

By the time Kursk ended, the Wehrmacht had already experienced disasters on other fronts, including in North Africa. It was not until November 1942, by which time the battle of El Alamein had been fought and lost, and his forces were in full retreat, that Rommel was able to call upon the services of a Schlachtgruppe. By then, no single Gruppe had a hope of turning the tide of the war in North Africa.

Like its Eastern Front counterparts, I./SchlG 2 – the unit in question – was made up of three Staffeln of single-engined fighters (in this instance Bf 109Fs) and an attached Staffel of Hs 129 tank-busters. The latter was the second Hs 129 Staffel to be formed (after 4.(Pz)/SchlG 1’s activation at Lippstadt early in 1942). Set up late in September 1942 at Deblin-Irena in Poland, reportedly around a cadre of personnel supplied by the short-lived Pz.J.St. 92, 4.(Pz)/SchlG 2 was initially equipped with a dozen of the twin-engined Henschels. However, by the time the Staffel, commanded by Hauptmann Bruno Meyer, arrived at El Adem, south of Tobruk, on 7 November, this number had shrunk to eight, only four of which were serviceable. The Hs 129s nevertheless claimed a dozen British tanks knocked-out during their first reported action just one week later.

However, not renowned for their reliability at the best of times, the mixing of the Hs 129s’ Gnome-Rhône engines with Libya’s all-prevailing dust and sand was a certain recipe for disaster. After only a few more operations, during which two machines were lost when forced to land behind Allied lines, the Staffel was withdrawn to Tripoli. Here, attempts were made to produce a satisfactory sand filter for the recalcitrant powerplants, but without much success. When the advancing Eighth Army entered the Libyan capital on 23 January 1943, the remaining unserviceable Henschels were reportedly destroyed and the Staffel evacuated to Bari, in Italy, for re-equipment.