As we have already noted throughout this book, the Luftwaffe was primarily tactical in its outlook. It was also largely focused on warfare over land rather than water, a natural perspective given Germany’s landlocked location on the European continent. The result was that maritime air power was never convincingly embraced, despite its increasing importance as the war went on.

Until April 1939, the Luftwaffe’s maritime arm consisted of the Seeluftstreitkräfte (Naval Air Arm), divided into 14 Küstenfliergerstaffeln (coastal aviation squadrons) and one Bordfliegergruppe (ship-based aviation group). Reorganization that spring, however, resulted in the formation of two Fliegerdivisionen – Flieger Division Luft West and Flieger Division Luft Ost, acting as aerial support to the Kriegsmarine’s Marineoberkommando West and Ost respectively. One important point about this structure was that although naval in purpose it still rested under the authority of the Luftwaffe. Hermann Göring, being the possessive character that he was, never relinquished his grip over maritime aviation, depriving the German Navy itself of strategic control of this important asset.

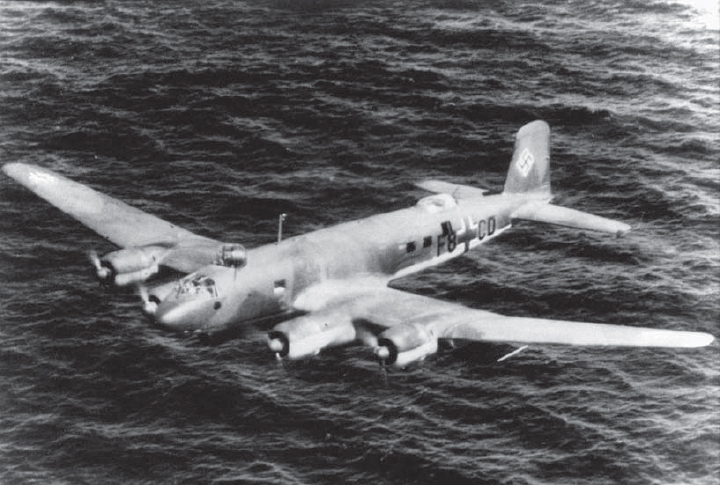

This tension at the heart of maritime aviation would have important repercussions in later years. After the fall of France in June 1940, the Third Reich was faced with only two strategic military options to deal with its remaining enemy, Great Britain. It could mount a direct assault on the home islands or it could adopt a blockade strategy and attempt to cut off the British economy from its overseas sources of raw materials. Adolf Hitler was never confident about mounting an invasion of Great Britain, and even before the Luftwaffe made its bid to force the British to the negotiating table during the Battle of Britain he authorized the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine to mount intensive attacks on British trade to bring their war economy to a standstill. While the Kriegsmarine had prepared for an attack on British trade routes with its U-boat arm, the Luftwaffe had not seriously considered long-range attacks on enemy shipping prior to 1940. Ju 87s and various medium bombers were repurposed for anti-shipping duties, with some considerable effect in the Kanalkampf, but for longer-range operations a very different type of aircraft was required. In a remarkable display of ingenuity, and within a very short time, the Luftwaffe was able to adapt existing long-range Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor civil airliners to the anti-shipping mission and scored some impressive successes against Allied convoys that had little protection from air attack. Although not built for war, the Condor established such a combat reputation that Winston Churchill soon referred to it as ‘the scourge of the Atlantic’.

In this chapter, we will look in depth at the role of the Condor in the battle of the Atlantic. As we shall see, this aircraft provides a useful starting point for understanding the Luftwaffe’s limitations and opportunities when it came to maritime warfare. From the Condor, however, we will broaden our analysis to consider the many other aircraft co-opted into anti-shipping warfare, and the ultimately losing battle they fought over the world’s seas and oceans.

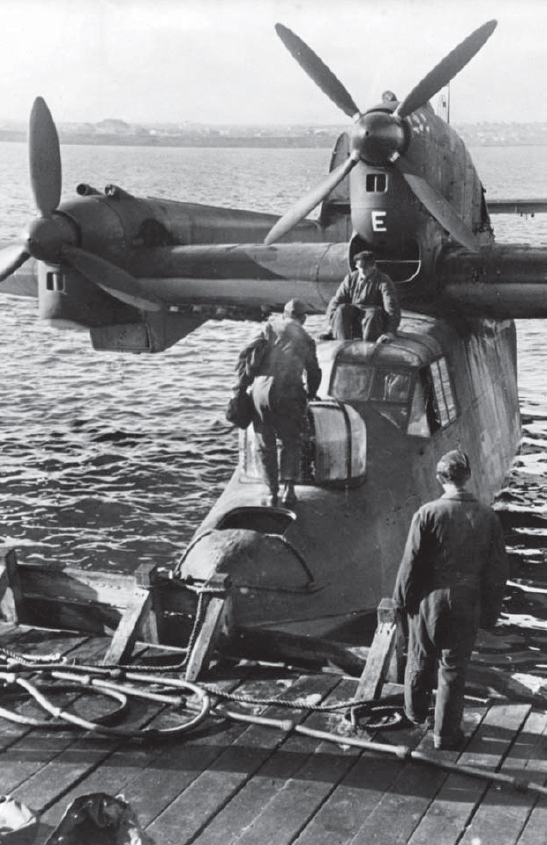

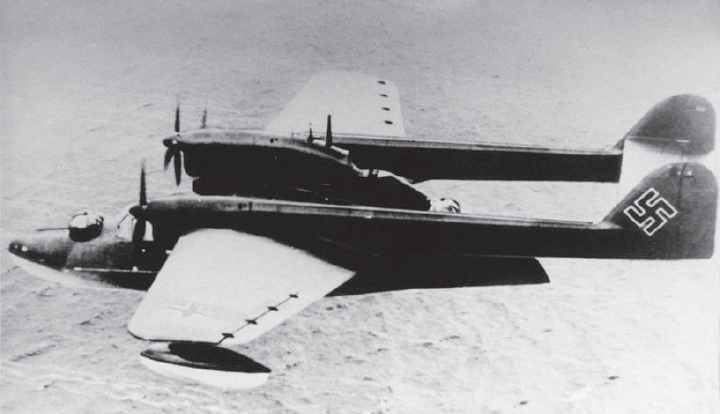

The Blohm und Voss Bv 138 was a long-range maritime reconnaissance flying-boat. It had a maximum range of 4,300km, and had a distinctive three-engine stack above the wing. It could also be fitted with 500kg thrust-assisted take-off rockets.

Once Hitler came to power in 1933, his regime was greatly interested in expanding the development of Germany’s aviation industry and in conducting propaganda coups that would enhance the international prestige of the Third Reich. Whenever possible, these two policy goals were to be combined. The German national airline, Deutsche Lufthansa, offered excellent potential to develop such new dual-use technologies, both for future military applications and for shining a global spotlight on German technical prowess. The RLM, run by the former head of Lufthansa, Erhard Milch, was established to ensure close coordination between military and civil aviation.

Lufthansa was eager to carve out a dominant niche in the newly emerging commercial aviation market and in 1932 it had chosen the reliable Junkers-built Ju 52/3mce tri-motor as its standard passenger liner. By 1936, three-quarters of Lufthansa’s 60-strong aircraft fleet were of this one type. Unfortunately, the Ju 52 could only compete economically on the medium-range routes to Spain, Italy and Scandinavia, and its lack of a pressurized cabin was hardly state-of-the-art in passenger comfort. When the American-built DC-2 appeared in 1934, followed by the even better DC-3 in 1935, Lufthansa’s leadership knew that they needed a superior aircraft to the Ju 52 if they were going to compete for new long-haul routes to the Americas, Africa and the Far East. Developing a reliable means of transatlantic passenger service, which Lufthansa had been considering even before Hitler came to power, seemed a very attractive goal for German civil aviation. Initially, Lufthansa went with the ‘lighter-than-air’ approach, constructing the airships Graf Zeppelin and Hindenburg. These airships were used to validate long-range navigation techniques, but their inherent fragility and huge cost marked them more as test beds rather than the final solution.

Once the DC-3 appeared, Lufthansa wanted a new civil airliner with inter-continental range that would allow it to dominate the new routes. The RLM also favoured the development of long-range civilian airliners to compete with the new generation of American-built passenger planes, especially as Milch did not want the German aviation industry to fall behind foreign technological advances.

With the RLM’s blessing, Lufthansa began to approach the major German aircraft designers, but the two logical choices, Junkers and Dornier, proved less than helpful. Both companies were focused on developing bombers and winning large contracts from the Luftwaffe, rather than diverting scarce resources towards a small-scale civilian project. Although Junkers did agree to rebuild the prototype of its cancelled Ju 89 heavy bomber into a transport version known as the Ju 90, it would not initially commit itself to full-scale development. As a fallback Dr Rolf Stüssel, Lufthansa’s technical chief, approached Focke-Wulf Flugzeugbau GmbH in Bremen about the possibility of developing a long-range multi-engined passenger airliner. Compared to Junkers and Dornier, Focke-Wulf had negligible experience in building such large, all-metal aircraft.

Focke-Wulf had enjoyed a close relationship with Lufthansa since the late 1920s, providing it with the Fw A17, Fw A32, Fw A33 and Fw A38 single-engined passenger planes. Although Focke-Wulf lacked experience designing large, multi-engined aircraft, it made up for this deficiency with a high level of motivation and a ‘can-do’ attitude. In early July 1936, Stüssel and Lufthansa’s director, Carl-August Freiherr von Gablenz, met with Kurt Tank to discuss Focke-Wulf’s technical proposal for the new aircraft. Tank was an aeronautical engineer and test pilot who had been with Focke-Wulf for five years. As head of its technical department, he had recently designed the Fw 44 civilian biplane. Tank delivered an impressive presentation, convincing Stüssel and Gablenz that not only could Focke-Wulf design and build the new aircraft, but that a flying prototype could be ready within just one year. On 1 August 1936, Lufthansa signed an agreement with Focke-Wulf to develop an aircraft that could carry 25 passengers to a range of 1,500km, which the RLM designated as the Fw 200.

Tank was eager to make a name for himself as an aeronautical designer and he took to the new project with relish. The Focke-Wulf design team, led by Dr Wilhelm Bansemir, quickly sketched a layout for the all-metal aircraft and Tank began to procure off-the-shelf components such as American-built Pratt & Whitney S1E-G Hornet radial engines, although the production aircraft would actually use BMW 132 engines. Amazingly, Tank accomplished this feat on schedule, with the V1 prototype being designed and assembled within 12 months. Even before Tank took the V1 on its inaugural flight on 6 September 1937, Lufthansa’s leadership was so impressed that they pledged to order two more prototypes as well as three production aircraft. The airline kept its options open, however, and also showed interest in the larger Ju 90 passenger plane that made its first flight soon after the V1.

The Condor began its life as a civilian airliner, flying long-distance routes in competition with a new generation of American airliners. This Lufthansa Condor was used on the South Atlantic route.

Although Tank was keen to show off the prototype, which was named ‘Condor’, it took another year of further refinements before it was ready for long-distance flights. By the summer of 1938, Focke-Wulf and the RLM agreed to use the V1 prototype on a propaganda tour that would highlight the range and speed of the new aircraft. In June 1938, Kurt Tank flew the prototype from Berlin to Cairo with 21 passengers on board. On 10 August 1938, a selected crew flew the prototype non-stop from Berlin to New York, a distance of 6,371km in just under 25 hours. Few of the reporters who witnessed this historic event noticed that the Condor’s faulty brake system caused damage to its landing gear. Having set the transatlantic record, the prototype was sent on a round-the-world flight via Basra, Karachi, Hanoi and Tokyo, in November 1938. Emperor Hirohito of Japan personally met the crew and the Japanese were very impressed by the V1. However, when continuing on to Manila, the crew made a mistake with the fuel pumping system that caused the aircraft to ditch offshore. Despite the loss of the prototype and indications that this finicky aircraft was quite fragile, Tank had impressed the world with his Condor.

An Fw 200 Condor revs up its engines, while the groundcrew look on. In order to achieve the Condor’s remarkable 2,400km combat radius, Kurt Tank had six 300-litre fuel tanks installed in the former passenger compartment.

Converting this technological marvel into a profitable airliner proved to be more difficult than Lufthansa had realized. Since an Fw 200 cost almost three times as much as a Ju 52, the airline decided to order only three of them in 1938 and four more in 1939. The Condors were used on trial flights to Brazil and West Africa in 1939, further demonstrating the long-range capabilities of the aircraft, but these flights served more as a propaganda stunt than as a demonstration of the viability of a commercial passenger service. In order to keep the production line open and hopefully recoup its development costs, Focke-Wulf sought to export the Condor and sold two planes each to Denmark, Finland and Brazil. Two more were sold to the Luftwaffe to provide VIP transport for Hitler and other high-ranking Nazis, and in early 1939, the Japanese airline Dai Nippon Kabushiki Kaisha ordered a further five. The Imperial Japanese Navy was also interested in using the Condor as a maritime patrol bomber and asked Focke-Wulf to develop a military version. In March 1939, Focke-Wulf introduced the Fw 200 B as the standard production version and Tank selected the Fw 200 V10 (named ‘Hessen’) – which was the prototype for the new B-series model – as the basis for a militarized version of the Condor to meet the Japanese requirement. The V10 was equipped with cameras and five light machine guns but had no provision for carrying bombs. However, before the V10 was even ready, World War II broke out in September 1939. Lufthansa was forced to suspend most of its long-distance international flights, but kept a few civilian Condors serving the routes to Rome, Madrid and Stockholm. Six of the existing Condors were handed over to the Luftwaffe’s 4. Staffel of KG z.b.V. 105 for use as transports.

Although British Intelligence was convinced that the Luftwaffe was using Lufthansa as a test bed to covertly develop long-range bombers, the Luftwaffe leadership had no interest in the Fw 200 as a military aircraft prior to World War II. The Luftwaffe had begun developing the Do 19 and Ju 89 four-engined heavy bombers in 1936, but as they proved to be too expensive, both these projects were cancelled after just a few prototypes had been built. Subsequently the Luftwaffe leadership saw the Ju 86B passenger airliner as having potential use as a bomber and encouraged Lufthansa to order five of them. The Fw 200, however, was considered to be more a propaganda device than a potential weapon. Not expecting an imminent outbreak of war, the RLM had placed an order with Heinkel in early 1938 for the He 177, believing this would provide a long-range bomber for the Luftwaffe. The He 177 could carry 1,000kg of bombs over a distance of 6,695km, which far exceeded the capabilities of militarized versions of civilian airliners. Yet the aircraft would not make its first flight until November 1939 and would not be ready for operational use until 1941–42 at best.

German propaganda photo of a Condor crew receiving a pre-mission brief in 1941. During the winter of 1940–41, KG 40’s exploits against British shipping helped to restore some of the Luftwaffe’s lustre after its failure to defeat the RAF in the Battle of Britain.

Just before war broke out, the Luftwaffe realized that it needed some kind of offensive anti-shipping capability in case of hostilities with Great Britain, and Generalleutnant Hans Geisler, a former officer in the Imperial Navy, was ordered to begin forming the cadre of a new special-purpose unit. Once war began, Geisler’s embryonic unit was organized as the X. Fliegerkorps and it was tasked with attacking British warships and merchant ships in the North Sea.

At first, Geisler had three bomber groups with medium-range He 111s and Ju 88s, but he had no long-range aircraft. Since the He 177 bomber would not be ready for some time, Geisler ordered one of his staff officers, Hauptmann Edgar Petersen, to examine existing civilian airliners and determine if any would be suitable for use as auxiliary maritime patrol aircraft. Petersen initially looked at the Ju 90 passenger airliner, but only two had been completed before Junkers suspended the programme. On 5 September 1939, Petersen went to the Focke-Wulf plant and met with Kurt Tank. Once again energetic in promoting his design, Tank convinced Petersen that the six nearly completed Fw 200 Bs intended for Japan could be converted into armed maritime patrol aircraft in just eight weeks and that more could be built in a matter of months.

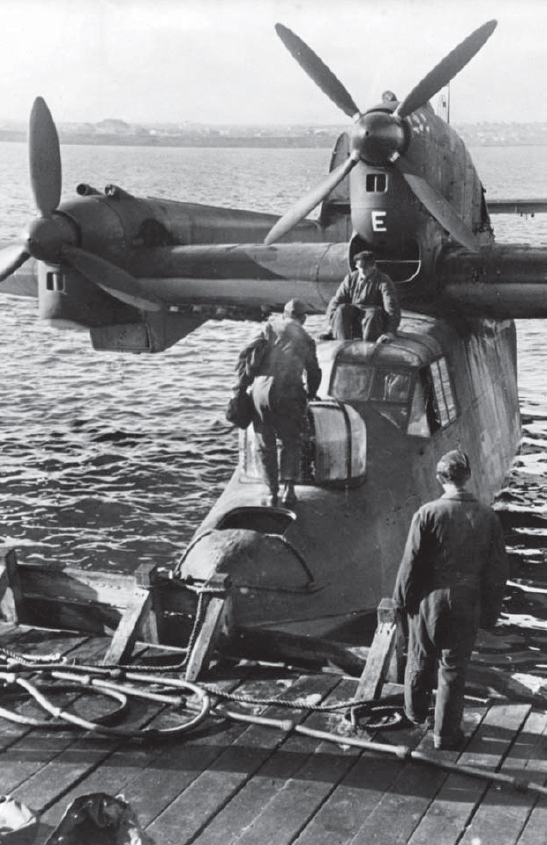

Fw 200 C3/U4 Condor

An Arado Ar 196 is prepared for launch from the rails of a Kriegsmarine warship. In naval service, the Ar 196 provided an over-the-horizon reconnaissance capability, gaining visual access of enemy ships well before closing to gun range.

Petersen wrote a memorandum after his visit to Focke-Wulf, recommending that X. Fliegerkorps use armed Condors for both maritime reconnaissance and attacks on lone vessels. Generalmajor Hans Jeschonnek, Chief of the Luftwaffe’s Generalstab, was reluctant to waste scarce resources on fielding an experimental unit with jury-rigged bombers, but General der Flieger Albert Kesselring, commander of Luftflotte 1, thought the concept was interesting and passed it on to Hitler. Petersen then found himself invited to Obersalzberg, where Hitler heard his briefing on the Fw 200 and gave approval to set up the new unit. With the Führer’s blessing, the Luftwaffe High Command sanctioned Petersen’s plan on 18 September 1939, and agreed to purchase the six nearly completed Fw 200 Bs intended for Japan, along with the two earmarked for Finland, and convert them into armed Fw 200 C-0 models. Even though the civilian version of the Fw 200 was priced at more than 300,000 Reichsmarks, Kurt Tank was so desperate to land a contract with the Luftwaffe that he sold these first aircraft to the RLM for only about 280,000RM each. Indeed, in 1939 Focke-Wulf only sold these eight Condors and six Fw 189 reconnaissance planes to the Luftwaffe, compared to the hundreds of aircraft sold by Dornier, Junkers and Heinkel. Jeschonnek also remained ambivalent about how the Fw 200 C should be used and Petersen was initially authorized to form them into a Fernaufklärungstaffel (long-range reconnaissance squadron), not an anti-shipping unit.

Although some sources identify the V10 prototype as the genesis of the armed Condor, it was only equipped with defensive armament. In order to meet the X. Fliegerkorps’ requirement for a reconnaissance bomber, Tank had to provide the Condor with the ability to both carry and accurately deliver bombs. This was no easy task since, in contrast to purpose-built bombers, the Condor did not have either a bomb bay or a glazed nose for the bombardier. Starting with a standard Fw 200 B, which was redesignated V11, Tank added a ventral gondola beneath the fuselage, which could carry a simple bombsight and two light machine guns. Rather than try to fit bombs internally, Tank installed hardpoints under the wings and outboard engine nacelles to carry a total of four 250kg bombs. He also added a small dorsal turret (A-stand) behind the cockpit and another dorsal MG15 position (B-stand) further aft. By removing all the seats from the passenger area and replacing them with internal fuel tanks, he increased fuel capacity by 60 per cent, which resulted in a combat radius of about 1,500km. Overall weight of the aircraft was increased by about 2 tonnes, but Tank was in such a hurry to deliver the Fw 200 C-0 to the Luftwaffe that he failed to strengthen the structure or examine the impact of carrying bombs and a heavy fuel load. The Fw 200 C-0 was also significantly slower than the civilian passenger version. Once completed in December 1939, the V11 was standardized as the Fw 200 C-1, which the Luftwaffe initially designated as the ‘Kurier’ to differentiate it from Condor civilian models.

On 10 October 1939, Hauptmann Petersen took command of the Fernaufklärungstaffel at Bremen. This Staffel, which was redesignated as 1./KG 40 in November, trained on unarmed Condor transports until the first Fw 200 C models began to arrive in February 1940. The RLM waited until 4 March 1940, to sign a series production contract with Focke-Wulf, which specified the construction of 38 Fw 200 C-1 and C-2 models for a fixed price of 273,500RM each, minus weapons. At that point, Focke-Wulf began serial production of the Fw 200 at the rate of four aircraft per month, a situation which remained in effect until 1942.

By the start of the invasion of Norway in April 1940, Petersen had a handful of operational Fw 200 C-0 and C-1s, which he used to conduct long-range reconnaissance missions around Narvik and to harass British shipping. Although Petersen’s unit was able to sink only one British merchant ship during the Norwegian campaign, some of the limitations of the Fw 200 were now realized and valuable experience was gained. Most of the pre-production Fw 200 C-0s that Tank had built so quickly suffered from cracks in their fuselage and wings, caused by the problems of overloading and a landing gear that could not handle rough airstrips. Furthermore, the defensive armament was quite weak and the lack of armour plate and self-sealing fuel tanks made the Fw 200 extremely vulnerable to even light damage. On 25 May 1940, a British Gloster Gladiator pilot intercepted one of KG 40’s Fw 200 C-1s over Norway and was amazed to see the aircraft crash after a brief burst of .303in. machine-gun fire. Petersen remained convinced as to the potential of the Fw 200, but recommended that Focke-Wulf quickly develop more robust and better-armed Condors in order to carry the fight to the British at sea. Kurt Tank spent the next three years trying to upgrade the Condor, increasing its range, armament and protection, but was never able to escape the fact that the basic design was poorly suited for a demanding combat environment.

The maritime strategic situation turned drastically against Great Britain with the German occupation of Norway by 8 June 1940, and the capitulation of France on 22 June. British pre-war planning by the Admiralty for trade protection had not expected the Luftwaffe to pose a significant threat in the Atlantic. Instead, the sudden German victories in Norway and France gave the predatory Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine unprecedented access to Britain’s transatlantic trade routes. Operating from French bases, even medium-range German aircraft could now attack British shipping in the South-west Approaches, the Irish Sea and on the convoy routes to Gibraltar. Just as enemy attack against convoys stepped up in August 1940, the Royal Navy was forced to keep a significant portion of its strength – including destroyers – in home waters to deter a possible German invasion.

Hitler’s main strategic objective after the fall of France was to force Britain to the negotiating table in order to gain an armistice, so that Germany could then throw its full weight against the Soviet Union. Never sanguine about conducting an amphibious invasion across the English Channel (despite the overt preparations for Unternehmen Seelöwe), Hitler preferred to exert pressure on Britain’s sea lines of communications to bring about the country’s submission. He was receptive both to Grossadmiral Erich Raeder’s recommendations to step up the war against Britain’s merchant convoys with his U-boats and surface raiders, and to Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring’s claims that his Luftwaffe could smash the RAF and then close Britain’s ports by bombing and mining them. This strategy appeared to offer the Third Reich a low-cost way to drive Britain out of the war, without risking a potential bloodbath in the English Channel. Accordingly, Hitler declared a total blockade of the British Isles on August 17, 1940, and authorized the Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe to sever Britain’s economic lifelines. Consequently, the role of the Fw 200 Condor anti-shipping operations should be considered in the context of the German strategic dynamic in 1940–41, which consisted of five concurrent but uncoordinated campaigns: air raids on ports, mining of coastal ports, and air, U-boat and surface warship attacks on convoys. If these campaigns had been properly coordinated, Germany had the means to strangle the British war economy. Yet the OKW failed to efficiently synchronize these five campaigns against British shipping and allowed the Luftwaffe and Kriegsmarine to conduct independent operations.

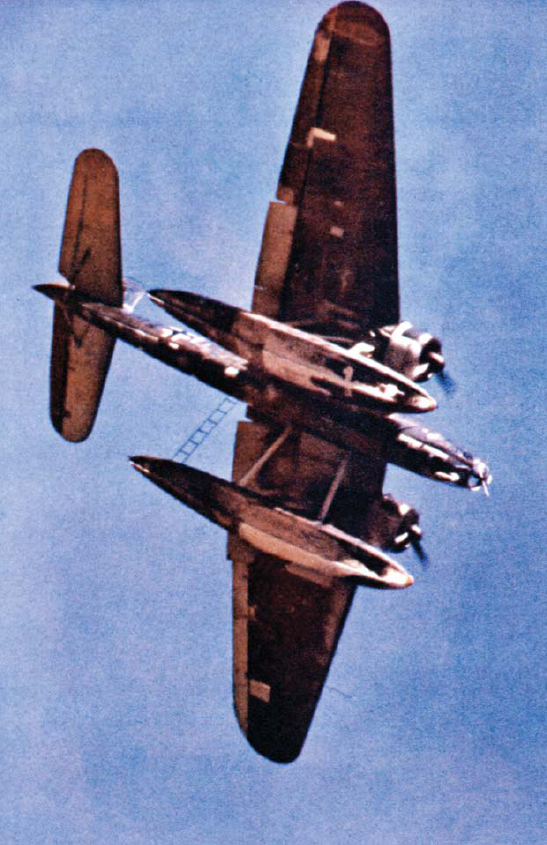

A German bomber defiantly displays its grim tally of Allied shipping, destroyed around the coasts of Norway and Britain. Strengthened Allied fighter escorts made coastal shipping a much harder target from 1941 onwards.

Generalfeldmarschall Hugo Sperrle’s Luftflotte 3 began attacks against British convoys in the Irish Sea with He 111 and Ju 88 bombers, but these aircraft only had an effective anti-shipping radius of operations of about 805km. Given this range restriction, the medium bombers had little time to search for maritime targets at sea and had to operate within range of British land-based fighters. The Fw 200 C, with an effective range that was triple that of other bombers, was the only aircraft that could conduct maritime air reconnaissance and anti-shipping operations beyond the range of British land-based fighters. Among the new tenants moving into French air bases soon after the 1940 armistice was a detachment of KG 40. It first operated from Brest in July, but then on 2 August 1940 began deploying to Bordeaux-Merignac, the same airbase from which Charles de Gaulle had fled on 17 June. By mid-August, Major Petersen had nine Fw 200s on hand, but operational readiness for the early C-1 model Condors rarely exceeded 30 per cent. The first batch of Fw 200 C-1s had been rushed into service and after just moderate use in the Norwegian campaign, many were sidelined by cracks in their fuselage and faulty brakes. Although the RLM placed orders for more and improved Fw 200s after the fall of France, Focke-Wulf was only able to deliver another 20 aircraft to I./KG 40 in the last six months of 1940. Amazingly, Focke-Wulf continued deliveries of civilian Fw 200 models to Lufthansa.

A British merchant vessel is attacked by a German bomber in 1940. Luftwaffe anti-shipping attacks accounted for the loss of dozens of vessels around the British coastline, and for a time the Royal Navy cancelled all naval traffic through the Channel straits.

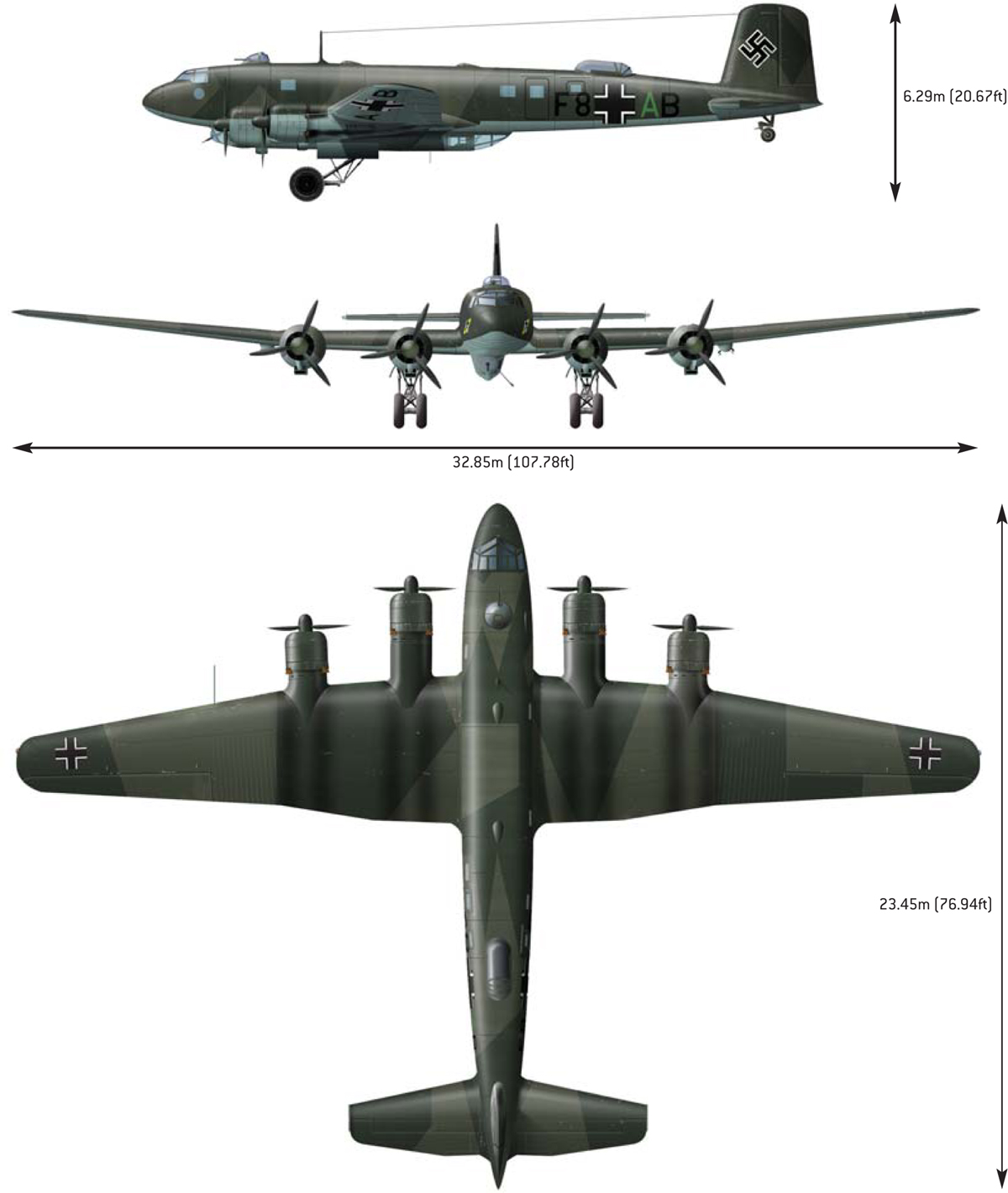

The Arado Ar 196 twin-float seaplane was a popular aircraft amongst its crews, being easy to fly and with good all-round visibility for the pilot and observer. It began the war in shipboard service, but then entered service with Luftwaffe coastal units in 1940.

Initially, the Luftwaffe did not know how to use the Fw 200 to best advantage. In July 1940, I./KG 40 fell under the 9. Flieger Division of Sperrle’s Luftflotte 3, which decided to employ the Condors in the aerial minelaying campaign. I./KG 40 conducted 12 night minelaying missions in British and Irish waters between July 15 and 27, which resulted in the loss of two Condors. Petersen complained about this costly misuse of his aircraft and at the end of July, I./KG 40 was switched back to maritime reconnaissance. Nevertheless, Petersen continued to argue for using the Fw 200s in an anti-shipping role and after Hitler’s blockade order, Sperrle decided to unleash Petersen’s Condors against the relatively unprotected British shipping west of Ireland. Even though Petersen rarely had more than four operational aircraft in 1940, his group began to steadily sink and damage enemy freighters around Ireland, and it was soon clear that the Condor had found its niche in the war.

1. Undercarriage de-icing cock

2. Suction-air throw-over switch (starboard)

3. Suction-air throw-over switch (port)

4. Instrument panel lighting switch (port)

5. Pilot’s oxygen pressure gauge

6. NACA cowling floodlight switch

7. Pilot’s control column

8. Intercom switch

9. Clock

10. Illumination buttons

11. Pilot’s repeater compass

12. Airspeed indicator

13. Gyro-compass course indicator

14. Turn-and-bank indicator

15. Course-fine altimeter

16. External temperature gauge

17. Rate-of-climb indicator

18. Artificial horizon

19. Coarse altimeter

20. Fuselage flap control lamp

21. Fuselage flap release handle

22. Radio beacon visual indicator

23. Gyro-compass

24. Gyro-compass heating indicator

25. Gyro-compass heating switch

26. Pilot’s rudder pedal

27. Pilot’s rudder pedal

28. Pilot’s seat pan (seat-back removed for clarity)

29. Compass installation

30. RPM indicator (port outer)

31. RPM indicator (port inner)

32. RPM indicator (starboard inner)

33. RPM indicator (starboard outer)

34. Double manifold pressure gauges (port engines)

35. Oil and fuel pressure gauges (port engines)

36. Oil and fuel pressure gauges (starboard engines)

37. Double manifold pressure gauges (starboard engines)

38. Pitch indicator (port outer)

39. Emergency bomb release

40. Pitch indicator (port inner)

41. Bomb-arming lever

42. Pitch indicator (starboard inner)

43. Pitch indicator (starboard outer)

44. Oil temperature gauge (port outer)

45. Oil temperature gauge (port inner)

46. Oil temperature gauge (starboard inner)

47. Oil temperature gauge (starboard outer)

48. Instrument panel dimmer switch

49. Undercarriage and landing flap indicators

50. Starter selector switch

51. Master battery cut-off switch

52. Ignition switches (port)

53. Ignition switches (starboard)

54. Landing light switch

55. Servo unit emergency button

56. UV-lighting switch

57. Longitudinal trim emergency switch

58. Directional trim emergency switch

59. Longitudinal trim indicator

60. Throttles

61. Supercharger levers

62. Fuel tank selectors

63. Throttle locks

64. Directional trim indicator

65. Directional trim switch

66. Undercarriage retraction lever

67. Airscrew pitch control levers (port)

68. Airscrew pitch control levers (starboard)

69. Wing flap lever

70. Parking switch activating handle

71. Fuel safety cock levers (port tanks)

72. Servo unit emergency pull-out knob

73. Fire extinguisher pressure gauge

74. Fuel safety cock levers (starboard tanks)

75. Fire extinguishers (port engines)

76. Fire extinguishers (starboard engines)

77. RPM Synchronization selector switch

78. Remote compass course indicator

79. Pitot head heating indicator

80. Airspeed indicator

81. Turn-and-bank indicator

82. Rate-of-climb indicator

83. Control surface temperature gauge

84. Course-fine altimeter

85. Artificial horizon

86. Cylinder temperature gauge

87. Cylinder temperature throw-over switch

88. Starting fuel contents gauge

89. Cruise fuel contents gauge

90. Cruise fuel transfer switch

91. Clock

92. Starting fuel transfer switch

93. Oil contents gauge

94. Starter switches

95. Suction and pressure gauges for undercarriage de-icing and gyro devices

96. Injection valve press buttons

97. Hydraulic systems pressure gauge

98. Windscreen heating

99. Control surfaces temperature switch

100. Fuel pump switches (port tanks)

101. Fuel pump switches (starboard tanks)

102. Controllable-gill adjustment

103. Airscrew de-icing levers (starboard engines)

104. Co-pilot’s seat pan (seat-back removed for clarity)

105. Co-pilot’s rudder pedal

106. Co-pilot’s rudder pedal

107. Co-pilot’s control column

When the Condor attacks began, Great Britain had four main convoy routes that were vulnerable to long-range air strikes: the HX and SC convoys on the Halifax-to-Liverpool run; the OA and OB convoys on the route between the southern British ports and Halifax; the HG and OG convoys running between Gibraltar and Liverpool; and the SL convoys from Sierra Leone to Liverpool. A snapshot of shipping on August 17, 1940, for example, would have shown 13 convoys at sea on these routes, made up of 531 merchant vessels and 22 escort warships. Most convoys received a strong escort three days out from Liverpool, but they crossed the Atlantic with minimal protection. The greatest danger of Condor attack therefore occurred when poorly escorted convoys were still about 965km out from Liverpool or Gibraltar and were beyond the range of effective land-based air cover.

Despite the Condor’s early successes against weakly defended British shipping, the Luftwaffe failed miserably to use KG 40 to best advantage in supporting U-boat attacks on convoys. With a limited number of operational aircraft available, KG 40 could only shadow a convoy for three to four hours and lacked sufficient aircraft to maintain contact for an extended period. In essence, KG 40 was only capable of sporadic maritime reconnaissance, not the consistent surveillance that the U-boats needed. Both Raeder and his U-boat chief, Vizeadmiral Karl Dönitz, were incensed that their small number of U-boats at sea had to waste valuable time searching for British convoys while the Luftwaffe failed to provide adequate maritime reconnaissance. Prior to the war, Raeder had lost the argument with Göring about creating an independent naval air arm to support the fleet and now the Luftwaffe High Command was unwilling to commit major resources to support maritime operations.

In November 1940, Britain’s only real offensive tool was RAF Bomber Command, and Churchill redirected it squarely at the Fw 200 threat by ordering raids against Bordeaux-Merignac airfield and the Focke-Wulf plant in Bremen. The first raid on Bordeaux-Merignac took place on the night of 22–23 November 1940, and saw 32 bombers destroy four hangars and two Fw 200s on the ground. Three follow-up raids were unsuccessful and it was not until the raid on April 13, 1941, that three more Condors were destroyed at the base. Bomber Command continued to raid the airfield on occasion, but Luftwaffe AA defences improved to the point that no more Condors were destroyed on the ground. Given that Bomber Command’s aircraft had little ability to hit point targets at night and were generally missing their aim points by about 3km or more in 1940–41, the fact that 191 sorties on Bordeaux-Merignac destroyed five Condors on the ground is remarkable. The first major raid against the Focke-Wulf plant did not occur until 1 January 1941 and, although it caused some minor disruption in Condor production, it only encouraged the company to shift much of the Fw 200 production inland to Cottbus.

Despite the inability of the British to intercept Fw 200s over water or destroy their bases and factories, the duel between the Condors and the British Atlantic convoys was ultimately shaped by each side’s different approach to inter-service cooperation.

In order to make Hitler’s blockade work, the Luftwaffe and the Kriegsmarine had to work together, which included using the Fw 200s to support anti-convoy operations in conjunction with the ongoing U-boat campaign. However, both services constantly squabbled over the best way to use KG 40’s Condors. Göring was more concerned about maintaining control over his air units than in helping the U-boats deliver a knockout blow against Britain’s convoys. Raeder temporarily gained Kriegsmarine control over KG 40 (while Göring was on Christmas holiday) when he sent Dönitz to brief the OKW on how the Condors could support the U-boat campaign. Dönitz claimed: ‘Just let me have a minimum of 20 Fw 200s solely for reconnaissance purposes and the U-boat successes will shoot up!’ Hitler obliged Dönitz by ordering I./KG 40 to be subordinated to the Kriegsmarine on 6 January 1941, but as soon as Göring returned from holiday he pressed Hitler to reverse his decision. Two months later, Hitler gave in and returned I./KG 40 to Luftwaffe control, but authorized the creation of the Fliegerführer Atlantik in Lorient to better synchronize Luftwaffe support for maritime operations. Generalmajor Martin Harlinghausen from IX. Fliegerkorps was appointed to this post and he made every effort to increase cooperation between KG 40 and the U-boats. Nevertheless, the Luftwaffe continued to divert KG 40’s planes and aircrew away from maritime operations to support special projects.

The Condor’s combat prowess rested on three primary capabilities: its ability to find targets, to hit targets and then to evade enemy defences. In 1940 the Condor had only a rudimentary capability of finding convoys and other suitable merchant targets. On a typical mission, an Fw 200 would fly about 1,500km from Bordeaux to look for targets west of Ireland, which would give the aircraft about three hours to conduct its search. Normally, Condors flew quite low (about 500–600m off the water), which made it easier to spot ships outlined against the horizon and avoided giving the enemy too much early warning. From this low altitude, the Condor could search an area of approximately 320km x 120km, with several of its crew scanning the horizon with binoculars. In decent weather, which was rare in the Atlantic, the observers might be able to spot a convoy up to 15–20km away, but cloud cover could reduce this by half. In 1941, improved Condors with longer range had four hours on-station time, increasing the search area by about 25 per cent. When the Condors gained a search-radar capability with the FuG 200 Hohentwiel radar in December 1942 and their on-station endurance doubled, their search area increased to nearly four times the size it had been in 1940. The Hohentwiel radar could detect surface targets up to 80km distant and its beam was 41km wide at that range. Nevertheless, the perennial problem remained for the Condors that due to limited numbers, KG 40 had difficulty maintaining a consistent presence along known convoy routes. With one sortie sent every day or so for three to eight hours, there was no guarantee that they would be operational at the very time a convoy was passing through the area. Thus the Condor’s actual ability to find targets was rather sporadic until late in the war, which accounts for the fact that KG 40 missed more convoys than it found.

As a converted civilian aircraft, the Fw 200’s ability to hit targets was severely limited by the lack of a proper bombsight and poor forward visibility. From the beginning, it was obvious that the Fw 200 could not attack in the way a normal bomber did, but had to rely on low-level attack (Tiefangriff) tactics. Approaching as low as 45m off the water at 290km/h, a Condor would release one or two bombs at a distance of about 240m from the target. This method ensured a high probability that the bomb would either strike the ship directly or detonate in the water alongside, causing damage. Although the early Condors only carried a load of four 250kg bombs, the low-level method made it highly likely that at least one ship would be sunk or damaged on each sortie that found a target. Since most civilian freighters were unarmoured and lacked robust damage control, even moderate damage inflicted would often prove fatal.

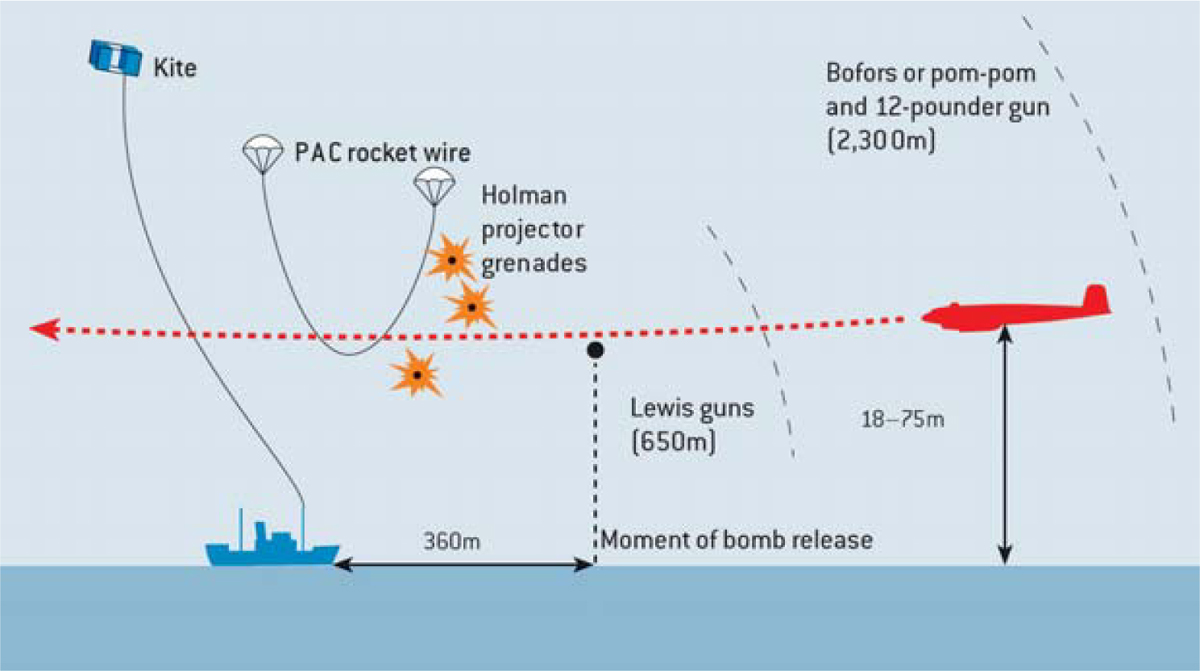

From a German diagram showing the variety of Allied responses to low-level attack, ranging from AA guns to rocket-launched cables. Note that this diagram shows a bows-on attack, when most attacks occurred either from astern or abeam. (© Osprey Publishing)

KG 40 became so adept at low-level tactics in early 1941 that some attacks scored three out of four hits. However, many of the bombs that struck the target failed to explode due to improper fusing – a nagging problem for the low-level method. Once the Condors shifted to attacks from 3,000m with the Lotfe 7D bombsight, which had a circular error probability of 91m with a single bomb against a stationary target, about one bomb in three landed close enough to inflict at least some damage. The Condors were also capable of low-level machine gun strafing. In 1940, a Condor using the low-level attack profile only had time to fire a single 75-round drum of ball ammunition from the MG15 machine gun in the gondola during each eight-second pass on a ship. This type of strafing inflicted little damage. Oberleutnant Bernhard Jope made three strafing runs on the Empress of Britain and wounded only one person on the vessel (his 250kg bombs, however, did far more damage). When improved Condors mounted larger 13mm and 20mm weapons in the gondola, firing AP-T and HEI-T ammunition, their strafing became far deadlier and the superstructures of merchant ships proved highly vulnerable to this type of fire. However, once Allied defences made low-level attacks too costly, the strafing capability of Condors was effectively neutralized.

The He 115 was an excellent seaplane, used for minelaying and torpedo-bombing in addition to reconnaissance duties. During the 1930s, the He 115 established eight world speed records for its class of aircraft.

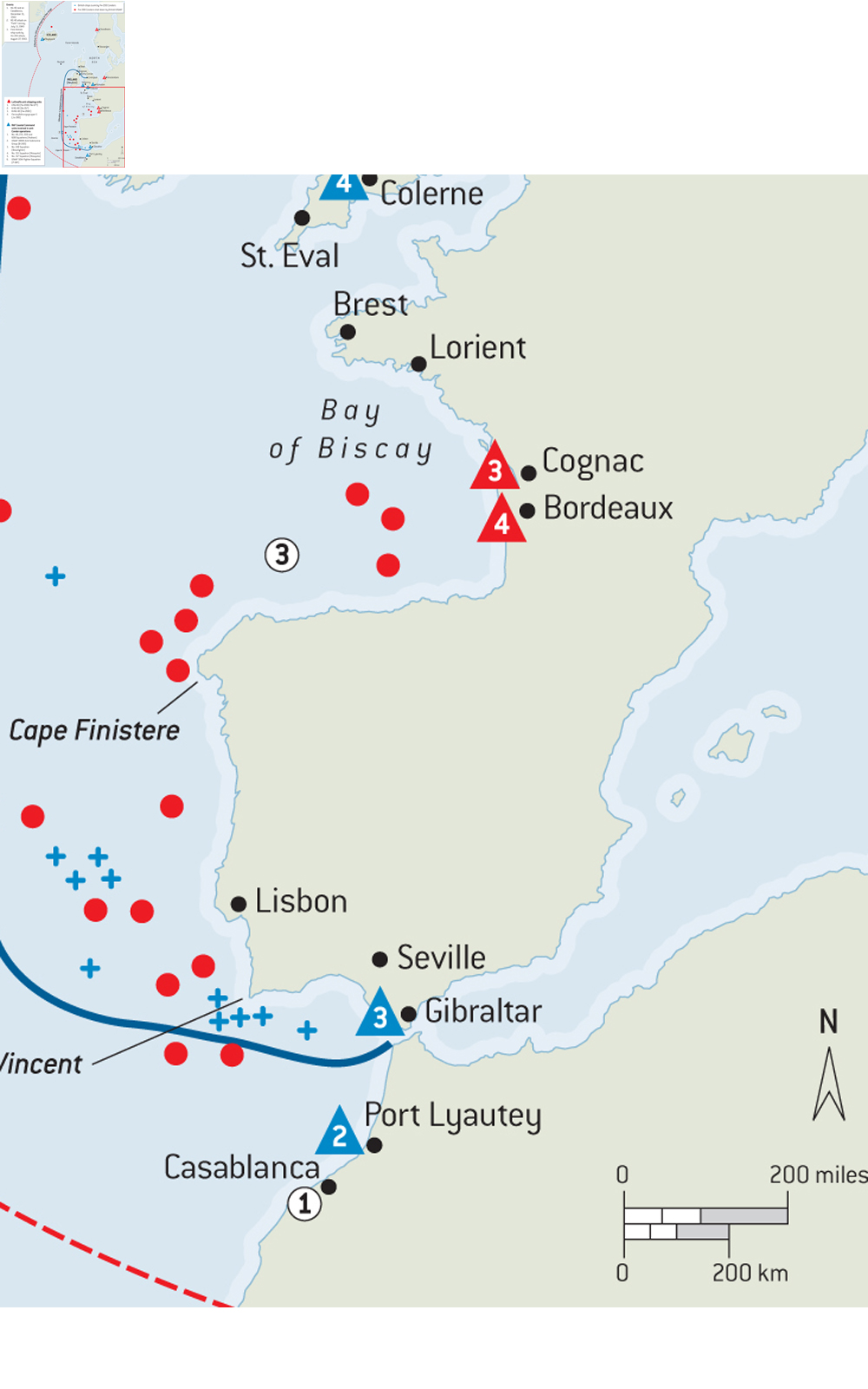

An Fw 200C-3 in flight. The C-3 model received a strengthened fuselage, a heavier bomb and fuel load, armour plating over key areas, an upgraded powerplant and a crew increase to seven members. Total strike radius was 1,750km.

The Condor’s ability to manoeuvre, absorb damage and evade enemy interception was always problematic. The Fw 200 B was built to fly in thin air at medium altitudes, with no sharp manoeuvring. Tank made the aircraft’s remarkable long range possible by designing a very lightweight airframe. Early military versions lacked armour plate, self-sealing fuel tanks or structural strengthening and the Condor was at least 2–4 tonnes lighter than other four-engined bombers in this class. Unlike purpose-built bombers that had some armour plate and redundant flight controls, the Condor was always exceedingly vulnerable to damage. When moderately damaged by a hit, chunks of the fuselage or tail often fell off, and the underpowered aircraft had difficulty staying in the air if it lost one of its engines. Even worse, there were six large unarmoured fuel tanks inside the cabin, which could turn the Condor into a blazing torch if hit by tracer ammunition. When Condors tried to manoeuvre sharply to avoid enemy flak or fighters, their weak structure could be damaged, leading to metal fatigue, cracks and loss of the aircraft. Defensive armament was initially weak but had improved greatly by the C-4 variant, causing enemy fighters to avoid lengthy gun duels with Fw 200s. Since the Condors were usually operating close to the water, they did not normally have to worry about fighter attacks from below, but this also severely limited their options. At these low altitudes, they were unable to dive and they could not out-turn or outrun an opponent. This limited them to ‘jinking’ to upset an opponent’s aim, hoping that the A- and B-stand gunners would score a lucky hit on the pursuing fighter. Thus the Condor essentially had poor evasion capabilities, which ultimately was a major contributor to its operational failure.

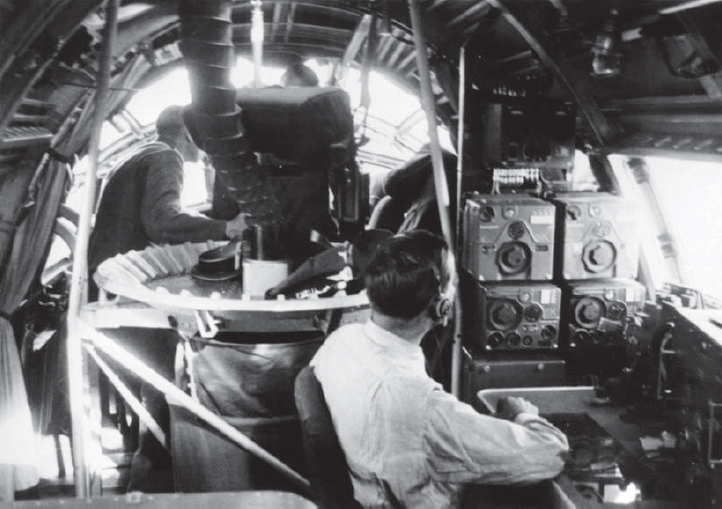

During the course of the war, the size of the Fw 200 crew increased from five members to six, and finally to seven. Each aircraft had a Flugzeugführer and co-pilot/bombardier, as well as a Bordfunker, a Bordmechaniker and a Bordschütz. As defensive armament increased, another Bordschütz was needed and in 1943, another Bordfunker was added to operate the radar. The airmen on Condors required a great deal of training and experience to function as a well-knit team on this complicated multi-engined aircraft. Small mistakes, such as failing to properly monitor fuel flow to the engines in a shallow dive, would lead to aircraft losses. Also, the Fw 200 crews often had to operate alone, almost always over water and at great distances from any friendly assistance. Crews had to learn to be efficient and self-reliant to avoid ending up at the bottom of the Atlantic.

In the beginning, KG 40 benefited from a cadre of Lufthansa aircrew with some experience on the Fw 200, although commercial passenger missions were considerably different from low-level anti-shipping attacks. Even experienced pilots like Edgar Petersen had to learn through experience the difficult art of finding convoys at sea. In August 1940, with only a handful of aircrew having any experience in low-level anti-shipping strikes, KG 40 had to gradually familiarize its personnel with their unique mission, and develop a set of effective tactical procedures as the best means to attack enemy shipping. Petersen was sparing of his crews and precious aircraft and he wisely refused to commit crews to long-range Atlantic missions until he judged they were ready, which limited the group to a low sortie rate in the autumn of 1940. Under these circumstances, I./KG 40 was not a fully trained or combat-ready group until spring 1941.

Like all Luftwaffe bomber pilots, the men who flew Fw 200s required about two years of flight training before they reached KG 40. After completing their initial flight training in the first year, they progressed to multi-engined aircraft, blind-flying school and advanced navigation. Once they had gone through the standard Luftwaffe pilot schooling, they were transferred to KG 40’s conversion unit, IV.(Erg)/KG 40, which was stationed in Germany until January 1942. This unit trained pilots and other aircrew on over-water operations using half-a-dozen of the original unarmed Fw 200s and some He 111s and Do 217s. In 1942, Condor conversion training was shifted to central France. The following year, the conversion group also began to conduct He 177 training, as the Fw 200 began to be replaced.

In 1940, all Condor pilots were officers, usually Oberleutnante, with the rest of the crew consisting of Feldwebel or Unteroffiziere, apart from the gunners, who were Obergefreite. By 1942, KG 40 was finding it difficult to keep up with high officer losses so more aircraft were flown by NCOs.

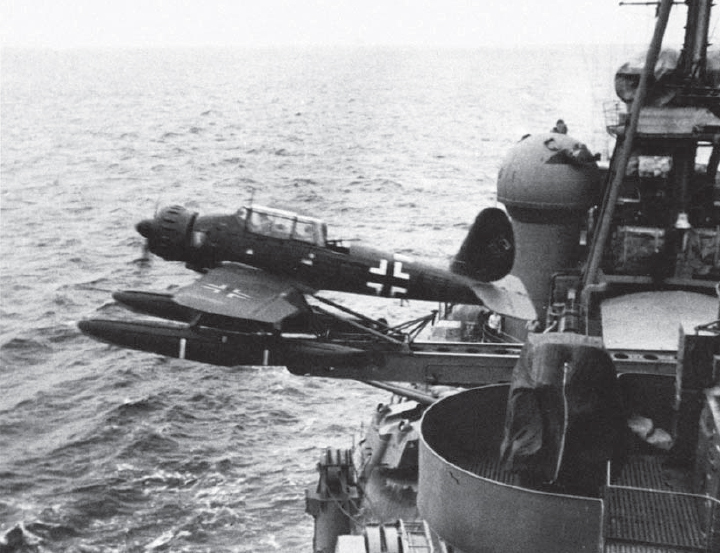

An He 115 seaplane of KG 54 is readied for action. Some of the type’s earliest combat operations in World War II involved minelaying sorties off the British coastline, and it was later used heavily in missions against the Arctic convoy, flying from bases in northern Norway.

A typical KG 40 Condor sortie from Bordeaux-Merignac would see the crew rising around midnight, eating breakfast and then heading to a target briefing. Usually sorties were directed towards known convoy routes where either U-boats or the Kriegsmarine’s B-Dienst (Intelligence Service) had detected recent traffic, although the information could be 12–24 hours old by the time the crew received it. Unlike a standard bomber mission against a fixed target, the Condor was assigned a search area where either moving convoys or independently steaming ships were expected to pass through. While the navigator plotted the appropriate course, the ground crews finished fuelling and arming the plane. If more than one Fw 200 was involved in the mission, they would coordinate their search zones to cover the maximum amount of area near the suspected convoy. Between 0100 and 0200hrs, the aircraft would take off and head west towards the convoy routes. Usually, the Condor would reach its search zone in about six hours, after a long boring flight over the Atlantic. In 1940–42 there was little or no risk of enemy interception on the outbound leg, but by 1943 aircrews had to be alert for enemy air activity over the Bay of Biscay. During the outbound leg, Condors flew in radio silence, even if operating with several aircraft.

Convoy HG 53 left Gibraltar on the afternoon of 6 February 1941, bound for Liverpool with 19 merchant ships escorted by the destroyer HMS Velox and the sloop HMS Deptford. U-37 spotted the convoy and attacked at 0440hrs on 9 February, sinking two ships. The U-boat captain reported the sighting, which was relayed to KG 40 in Bordeaux. Rather than sending one or two Condors as usual, KG 40 launched its first mass attack against a convoy with five Condors, led by Hauptmann Fritz Fliegel. They found the convoy 640km south-west of Lisbon around 1600hrs. One Condor quickly scored hits on the steamer Britannic, which sank in minutes. As the Condors began another run, the convoy opened fire with every available gun and HMS Deptford was able to damage the wing of Oberleutnant Erich Adam’s Condor. Adam managed to complete his bombing run but had to land in Spain due to the loss of fuel. Nevertheless, the four remaining Condors sank four more steamers. Here, Schlosser has just turned away after hitting the Britannic, while Adam is beginning his bomb run on the steamer Jura. (Howard Gerrard © Osprey Publishing)

Finding convoys or independent ships proved to be far more difficult than Petersen expected. The combination of stale intelligence and poor long-range navigation skills over water led to many of the early Condor missions failing in their task. Convoys were usually difficult to spot, particularly in overcast winter weather over the Atlantic, when visibility was often reduced to only a few kilometres. Once a Condor arrived in its target area, as many of the crew as possible would use binoculars to scan the sea for shipping while the pilot flew several search legs through the zone. If multiple aircraft were involved in the mission, they would split up at this point to cover their individual areas. Typical endurance in the search area was initially about three to four hours, but this was extended as improved Fw 200 models arrived in 1941–42.

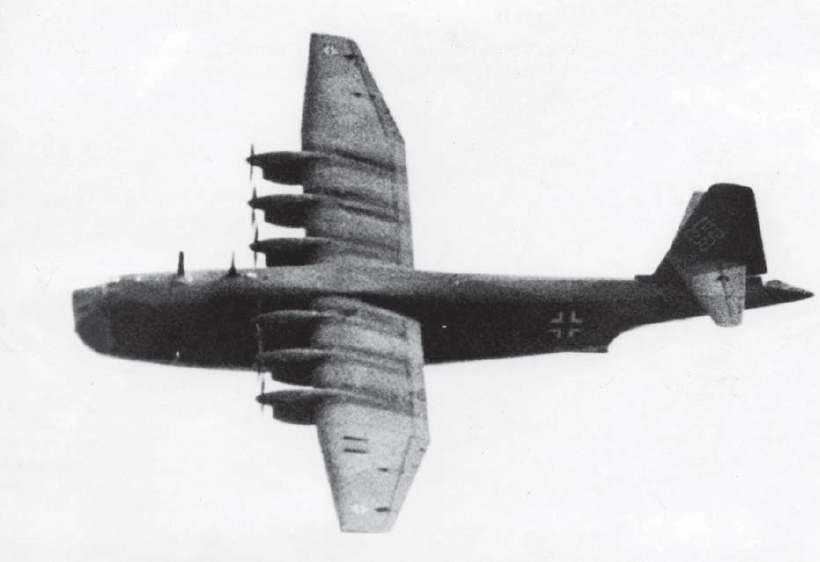

The tail of this Fw 200 Condor is adorned with the record of its maritime kills. The figures also include the tonnage of each vessel sunk. Although the Condor became a leading Luftwaffe anti-shipping aircraft, ultimately it was specially adapted medium bombers that shouldered much of the burden of the maritime war.

If a convoy or other significant target was spotted by the observers, the pilot would usually manoeuvre in closer, using clouds for concealment as much as possible, and observe the target for a while. The Bordfunker would break radio silence to vector in other Condors if they were nearby, so as to mount a coordinated attack. During this observation phase, which could last up to an hour, the crew would try to identify the escorts, if any, as well as the best targets to attack. Ideally, the Fw 200 sought its victims from stragglers or ‘tail-end Charlies’, minimizing the risk of defensive fire. Since the early Condors lacked an effective bombsight, strikes were only possible at low level. Martin Harlinghausen had developed the ‘Swedish turnip’ attack method with X. Fliegerkorps, which entailed approaching the target from abeam at a height of 45–50m and then releasing the bombs about 300–400m short of the target. Ideally, the bombs would glide into the target, striking at the waterline. This method offered a high probability of a hit, but also exposed the attacking aircraft to the vessel’s AA guns (if it was equipped with any).

KG 40 used the ‘Swedish turnip’ extensively in 1940–41 but many pilots preferred the safer approach of attacking from dead astern. From that angle the chances of a hit were reduced, but it was safer for the Condor as the DEMS ships normally carried their AA guns towards the bow. Just in case, most Fw 200s would use their ventral machine guns or 20mm cannon to strafe the decks, in order to suppress any flak gunners.

Normally, a Condor would make several passes on a target, dropping only one or two bombs each time. As it overflew, hopefully not taking too much AA fire, the pilot would pull up sharply and turn around for another pass, or if the first attack was successful, shift to another target. Once all bombs were expended, the Condor would depart, heading back either to Bordeaux, or to Værnes in Norway. From Værnes, it would return to Bordeaux via Bremen, giving Focke-Wulf the chance to repair any damage or mechanical defects. With an individual aircraft usually taking anything from a few days to a week to do the entire return cycle, this system further reduced the operational sortie rate, but helped keep the available Condors in satisfactory shape.

Condor operations from Bordeaux-Merignac began sporadically in mid-August 1940 and continued from that location until July 1943. The first operations were tentative and designated as armed reconnaissance sorties rather than as anti-shipping strikes. Three days after Hitler announced his blockade of the British Isles, the Condor’s participation in events began inauspiciously when an Fw 200 C-1, sent to check for Allied shipping west of Ireland, developed mechanical difficulties and was forced to conduct a belly-landing near Mount Brandon on the south-west coast. Petersen was able to mount a few sorties with his remaining two operational Condors and they succeeded in sinking the SS Goathland, a 3,821-tonne merchant ship sailing alone, on 25 August. Five more ships were damaged west of Ireland by the end of August. The situation did not improve much in September, when KG 40 sank just one Greek freighter and damaged nine other ships. A further small freighter was sunk on 2 October and the 20,000-tonne troop transport Oronsay was damaged on 8 October. After eight weeks of limited operations, KG 40 had sunk only three ships totalling 11,000 tonnes and damaged 21 ships totalling about 90,000 tonnes. Bombing accuracy was poor, with most damage inflicted by near-misses. In reality the Condor appeared to have difficulty inflicting enough damage to actually sink ships and seemed to be more of a nuisance than a lethal threat. Given that U-boats sank more than 500,000 tonnes of shipping in the same period, the British Admiralty was not unduly disturbed at the Fw 200’s combat debut.

Flying-boat crews stand to attention for a visit by Grossadmiral Erich Raeder, the commander-in-chief of the German Navy. The Kriegsmarine also operated its own maritime aircraft, although the Luftwaffe retained control of much of the aerial anti-shipping campaign.

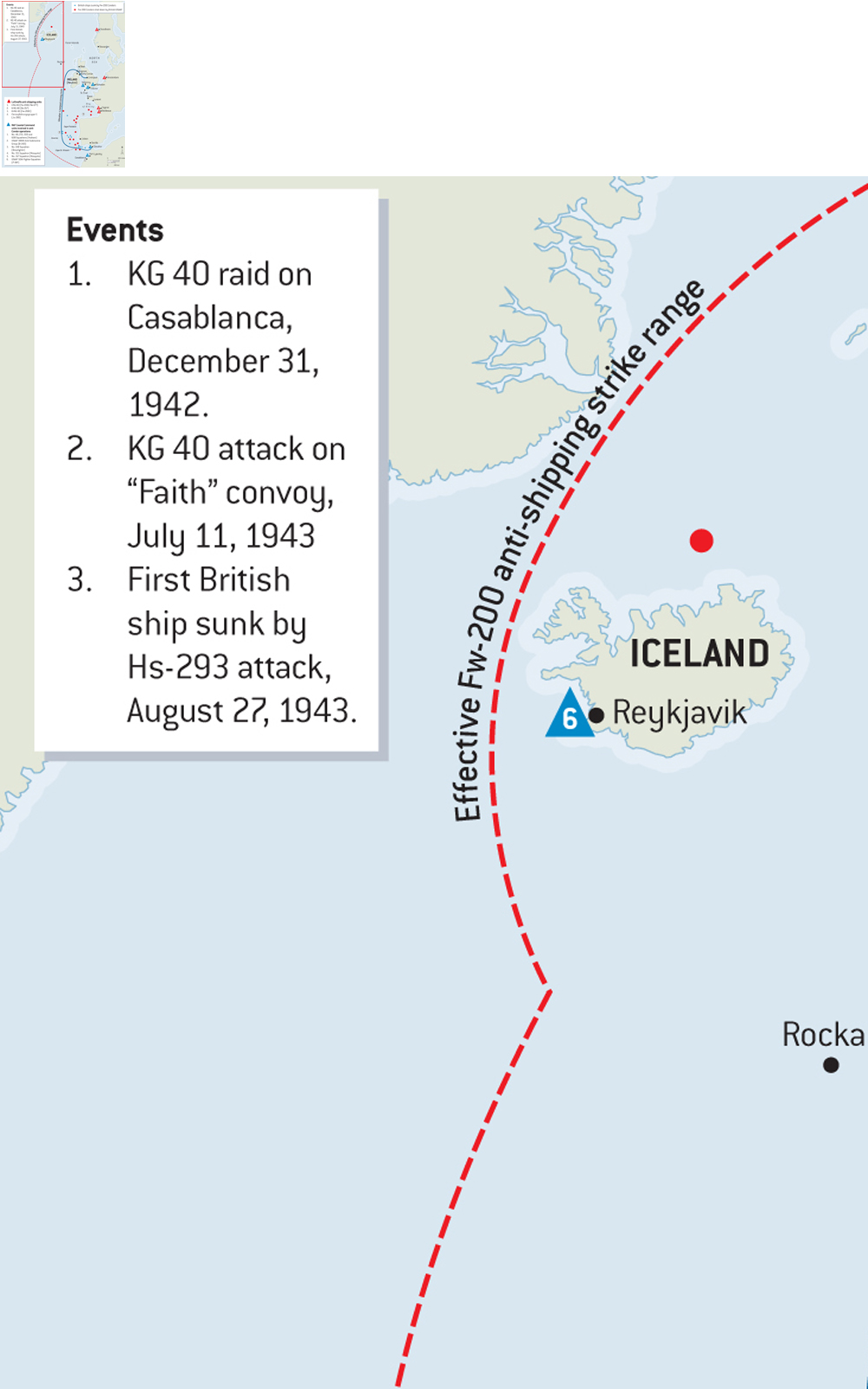

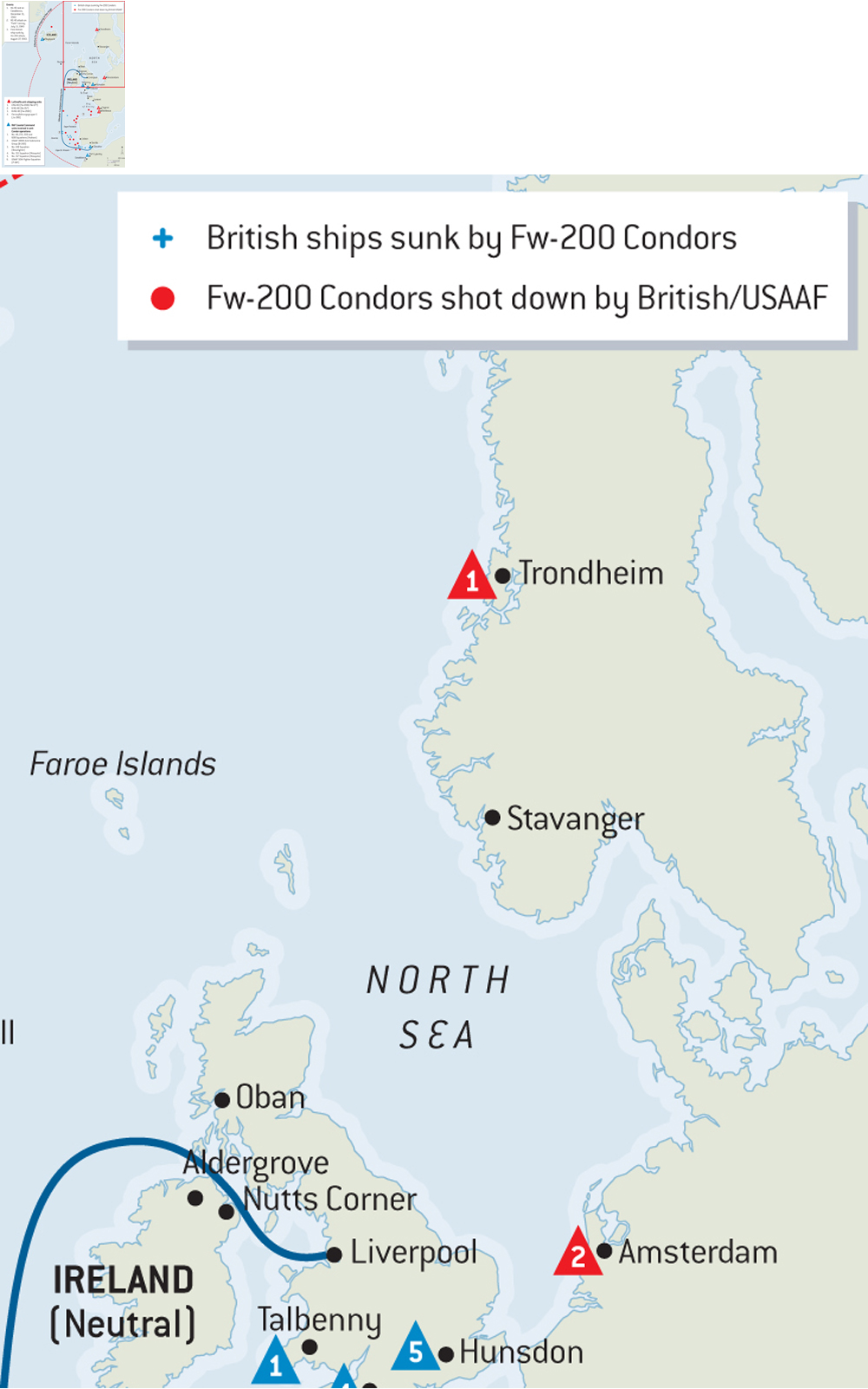

Condor attacks on British shipping, 1943. (© Osprey Publishing)

However, this attitude was forever altered when Oberleutnant Bernhard Jope crippled the 42,348-tonne ocean liner Empress of Britain on the morning of 26 October (U-32 finished the liner off on 28 October). The Empress of Britain was the largest British vessel sunk to date and her vulnerability to air attack shocked the Admiralty. Jope’s attack also convinced the Luftwaffe leadership that the Fw 200 was capable of more than just armed reconnaissance. On 27 October, a lone Fw 200 attacked convoy OB 234 west of Ireland. Despite the presence of nine escort vessels, a Condor succeeded in damaging the 5,013-ton vessel Alfred Jones. An RAF Hudson from No. 224 Sqn based at Aldergrove in Northern Ireland arrived on the scene but when it attempted to interfere with the Condor attack, the Fw 200’s gunners riddled it with 7.92mm fire. This attack was the first time that a Condor deliberately targeted a convoy.

An Fw 200 Condor at its airbase in France. The fall of France in 1940 meant that the Luftwaffe was able to project its reach deep out into the Atlantic, using the long-range Condor in anti-shipping and reconnaissance capacities.

In November, Petersen began to ramp up KG 40’s operational tempo against lucrative targets off the north-west coast of Ireland. By Christmas, KG 40 had sunk 19 ships of 100,000 tonnes and damaged 37 ships of 180,000 tonnes, while British convoy defences had failed to destroy a single Condor. The first round in this duel had clearly gone to the Luftwaffe. KG 40 now had enough trained crews and new aircraft to form two complete operational Staffeln of six Condors each. It was also over New Year that the Kriegsmarine temporarily gained tactical control over KG 40.

Rested over the holidays with home leave in Germany, KG 40’s crews returned with a vengeance on 8 January 1941, when they attacked the 6,278-tonne cargo ship Clytoneus near Rockall and scored a direct hit that split the unfortunate vessel wide open. Again and again over the next weeks, KG 40 exploited the feebleness of the Royal Navy’s low-level air defences and RAF Coastal Command’s failure to provide effective air cover, enabling it to savage one convoy after another. By the end of January, the surge in Condor attacks had sunk 17 ships of 65,000 tonnes and damaged five others. Yet if January was bad for the British, February 1941 was worse. KG 40 continued to pick off individual merchant ships west of Ireland with single-plane sorties but on 9 February Peterson shifted tactics and area of operations. He sent five Fw 200s, flown by the best pilots in the group, against convoy HG 53, which had been detected by U-boats south-west of Portugal. Aside from a few two-plane sorties, KG 40 had not previously launched multi-plane strikes against a single convoy and this attack caught the British by surprise. The Condors only sank five small ships, but they caused the convoy to scatter so badly that U-37 was able to slip in and sink three more. This was the classic joint attack that Dönitz had envisioned when he lobbied for the Fw 200 and it proved devastating in practice. The Kriegsmarine was quite pleased with the success of KG 40’s Condors in February; they had not only managed to sink 21 ships of 84,301 tons, but had also improved the lethal nature of wolfpack tactics by introducing a new combat dynamic – daylight air attacks to scatter the convoy, followed up by massed U-boat night attacks. Despite the promise these tactics held for winning the Battle of the Atlantic, the Condors had in fact already reached their high-water mark.

In March, the Luftwaffe regained control over KG 40 and put it under Martin Harlinghausen as Fliegerführer Atlantik. Yet problems for the Condors were mounting. Losses of aircraft were increasing significantly from more effective British AA fire and the predations of RAF Coastal Command aircraft. Better convoy tactics meant that the Condors often struggled to find enemy ships in the first place, and when they did the attacks were frequently ineffective. Thus in July 1941, KG 40 shifted entirely to the maritime reconnaissance role and only authorized anti-shipping attacks against lone vessels. Condors therefore succeeded in locating four convoys for the U-boats in July, but they sank no ships themselves.

A British Martlet fighter flying from the auxiliary aircraft carrier, HMS Audacity, destroys an Fw 200 C-3/U4 flown by Oberleutnant Karl Krüger on 8 November 1941. Both Krüger and his co-pilot were killed as the windscreen shattered under the fusillade. (Howard Gerrard © Osprey Publishing)

The last six months of 1941 confirmed the operational decline of KG 40. Only four ships of 10,298 tonnes had been sunk in anti-shipping operations with two more damaged, whereas 16 Condors had been lost, including seven shot down by convoy defences. Although the Condors had enjoyed some success in guiding U-boats towards convoys, it was clear that the days of easy low-level air attacks were over and that the duel for supremacy over Britain’s lifelines had turned against the Germans.

In March 1942, it was decided to send Major Edmund Daser’s I./KG 40 to Værnes airfield near Trondheim to provide long-range reconnaissance for Luftflotte 5 against the Arctic convoys. Major Robert Kowalewski’s III./KG 40, which was still converting from He 111s to Fw 200s, would remain at Bordeaux and continue to operate against the Gibraltar convoys. Fliegerführer Atlantik was stripped to the bone to provide anti-shipping units for Norway, which effectively brought the aerial blockade of Great Britain to an abrupt end.

The Luftwaffe’s operations in the far north illustrate the fact that Fw 200s were far from the only aircraft type employed in maritime missions. In fact, compared with other aircraft involved in such operations, such as the He 111H, Ju 88 and Do 217E, the Fw 200 had a very low operational readiness rate – often as low as 25 per cent. It also suffered from a very high level of non-combat losses, at 52 per cent, compared to 35–38 per cent for all aircraft losses typically suffered by the seven other bomber Gruppen supporting Fliegerführer Atlantik. Based upon the results of operations to date, Fliegerführer Atlantik reported on 3 December 1942, that ‘because of inadequate armament, the Fw 200 is unfit for use in areas that are within range of land-based fighter planes. Confrontations between the Fw 200 and such fighters in medium cloud cover almost always lead to the destruction of the Fw 200. Further development of the Fw 200 cannot be recommended because its development has reached its limits and the aircraft should be replaced by the He 177.’

Fliegerführer Atlantik, and indeed all the Luftwaffe formations with an anti-shipping or maritime reconnaissance purpose, had numerous specialist aircraft to draw upon. At the smaller end of the scale were a range of single-engined floatplanes, such as the Heinkel He 60 (a biplane removed from service in 1943), Heinkel He 114 and Arado Ar 196. The latter, for example, was initially a Kriegsmarine aircraft, embarked aboard great battleships such as Deutschland, Admiral Graf Spee, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, plus a variety of heavy and light cruisers. In mid-1940, with French ports now in German hands, the Ar 196 was taken widely into Luftwaffe service, to perform coastal reconnaissance and light maritime attack duties, particularly against Allied submarines operating in the Bay of Biscay. The aircraft did not offer overwhelming performance. Powered by a single 723kW BMW 132K radial engine, the aircraft had a maximum speed of just 310km/h, a range of 1,070km and an armament of two forward-firing 20mm cannon, a forward-firing 7.92mm machine gun, two backwards-facing trainable 7.92mm machine guns in the rear cockpit, and a maximum bomb load of 100kg (one 50kg bomb under each wing). Thus armed, it was capable of giving a merchant vessel or surfaced submarine more than enough cause for concern, although if ‘bounced’ by enemy monoplane fighters it would find itself at a severe disadvantage.

Only a single example of the Bv 238 was produced in World War II, and it constituted one of the largest aircraft of the war. It had a crew of 12, a wingspan of over 60m and a length of 43m.

In addition to light floatplanes, the Luftwaffe also deployed a remarkable range of more substantial two-engined aircraft. The ageing but robust He 59 was put to a myriad of uses. It acted as a minelayer (it could deploy two 500kg magnetic mines), a reconnaissance aircraft and an air-sea rescue aircraft – in this latter role it rescued 400 German aircrew from British waters during the Battle of Britain. It was even used as an assault transport aircraft, flying German assault units into Norwegian fjords in April 1940, and landing on the River Maas the following May during actions to seize Dutch bridges. Similar versatility was also offered by the He 115, which like the He 59 was also capable of carrying a single torpedo for anti-shipping duties.

The true workhorses of Germany’s anti-shipping campaign, however, were actually variants of its medium bomber fleet, particularly the He 111 and the Ju 88. The He 111, in its initial guise as a land bomber, was not particularly suited to maritime work, as its level-bombing tactic gave poor accuracy against a ship far below taking evasive manoeuvres. Yet its availability, range and serviceability meant that aircraft designers soon looked for ways in which it could be converted to anti-shipping duties. The solution was found in the He 111H torpedo-bomber, which mounted two 765kg LT F5b torpedoes under its wing roots. This type of aircraft began operations against the Allied Arctic convoys in mid-1942 with some success. In an operation against convoy PQ18 in September 1942, 42 He 111s accounted for eight out of 13 ships sunk. (They were supported by 35 Ju 88s, which confused the Allied response by delivering dive-attacks mixed in with the He 111’s level attacks.)

The Bv 222 was another hefty flying-boat in the Luftwaffe inventory. Only 13 examples of the six-engine aircraft were produced, operating principally around Mediterranean and northern European waters. As a transporter, the Bv 222 could carry around 90 fully armed troops.

An Fw 200 Condor undergoes engine maintenance. The Condor was powered by four 1,000hp Brahmo 323 R-2 supercharged radial engines, and had a cruising speed of 335km/h.

The He 111H forces in the far north were, in late 1942, redeployed for service in the Mediterranean. This move was prompted by the Allies’ increasingly heavy use of fighter escorts to protect its convoys, plus the deteriorating weather of the far north. In sunnier climes it continued to perform its duties well, albeit under the undeniable loss of air superiority. There it also fought alongside another of the Luftwaffe’s great anti-shipping aircraft, the Ju 88. The Ju 88, through its dive-bombing capability, was always well-suited to maritime operations. Even its earliest variants, therefore, were used against naval targets during the battles of 1940–41. It was during the Greek campaign, however, that the Ju 88 demonstrated just how effective that could be in this role. The Junkers’ first success of the campaign was a devastating raid on Piraeus harbour. Serving as the destination for the vast majority of the supply convoys that had been bringing men and materials from Egypt since early February, Piraeus was packed with shipping on the evening of 6 April when 20 Ju 88s of III./KG 30 lifted off from Catania.

As well as delivering anti-shipping and reconnaissance duties, large seaplanes were also extremely useful for coastal resupply missions. Here we see a Bv 222 offloading supplies in a North African port; the aircraft could carry up to 20,000kg of supplies.

An He 115 is bombed-up. The aircraft could take up to 1,250kg of bombs and/or mines, or it could carry a single 500kg torpedo on the centreline.

Most of the bombers were armed with just two aerial mines apiece, the intention being to block the narrow entrance to the harbour. However, Hauptmann Hajo Herrmann had ordered that his 7. Staffel machines should each be loaded with two 250kg bombs as well. At the end of the 748km flight to the target area, he did not want to see his mines drift down on their parachutes and simply disappear into the water. After all that effort, he was determined to attack the merchantmen berthed in the harbour – it was to prove a momentous decision.

The more heavily loaded aircraft of 7./KG 30 were flying the low position in the loose formation as the Ju 88s swooped down on Piraeus from the direction of Corinth at 2100hrs. After releasing their mines as directed, Herrmann’s crews made for the ships. At least three of the Staffel’s bombs – Herrmann’s among them – struck the 7,529-tonne Clan Fraser, a recently arrived ammunition ship packed with 350 tonnes of TNT, only 100 tonnes of which had been unloaded when the attack came in.

As well as the three direct hits, it was surrounded by near misses, which destroyed buildings and stores on the quayside. The initial blast lifted the vessel out of the water and snapped its mooring lines. The shockwave from the explosion was felt by Herrmann and his crew as their aircraft was thrown about ‘like a leaf in a squall’ 1,000m above the harbour.

However, worse was to follow. As the Clan Fraser drifted, its plates glowing from the fires raging inside her, the flames spread to other vessels in the harbour, including the 7,100-tonne City of Roubaix, which was also carrying munitions. Despite the danger, desperate efforts were made to get the situation under control. But the blazing ships could not be towed away for fear that they would hit a mine and block the harbour approach channel. Suddenly, in the early hours of 7 April, the Clan Fraser erupted in a giant fireball. Minutes later the City of Roubaix went up as well. The resultant series of explosions, which destroyed nine other merchantmen and devastated the port of Piraeus, shattered windows in Athens 11km away, and were reportedly heard over a distance of up to 241km.

In all, close on 100 vessels were lost, including some 60 small lighters and barges. Grievous as this was, the damage to the port of Piraeus itself was far more serious. In the explosions, described by one historian as ‘of near nuclear proportions’, it had been razed almost from end to end. Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham, Commander-in-Chief of the Mediterranean Fleet, called the raid on Piraeus a ‘devastating blow’. At a single stroke it had destroyed the one port sufficiently and adequately equipped to serve as a base through which the British Army could be supplied.

Ju 88A-4/Torp ‘1T+ET’ of 9./KG 26, Villacidro, Sardinia, April 1943. The history of III./KG 26 between 1940 and 1942 was particularly complex, even by Luftwaffe standards. Suffice it to say that during this period no fewer than three different Gruppen bearing designation III./KG 26 were formed. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

Piraeus would be closed to all shipping for the next ten days. During this time incoming vessels had to be diverted to other ports such as nearby Salamis, or Volos far up on Greece’s Aegean coast. Even after it had been partially reopened, such was the damage that it was no longer able to operate properly. The master of one vessel that put in to Salamis on 9 April and visited Piraeus two days later described the place as being ‘in a state of chaos caused by the explosion of the Clan Fraser, which had been hit while discharging ammunition. The ship had disappeared and blown up the rest of the docks, and pieces of her were littered about the streets.’

The man responsible for much of this chaos and mayhem, Hauptmann Hajo Herrmann, had not escaped totally unscathed. At some stage during the raid the port engine of his Ju 88 had been damaged by AA fire. And for safety’s sake, rather than risk the long flight back to Catania, he headed eastwards and landed on Rhodes – only to run his aircraft off the end of the runway!

In addition to port raids, Ju 88s were used extensively in anti-convoy duties, accounting for the loss of thousands of tons of Allied shipping sailing across the Mediterranean, despite no major anti-shipping modifications to its structure. However, recognizing that the Ju 88 had some talent in this area, the Luftwaffe did adapt the Ju 188 (a high-performance version of the Ju 88) to a more direct anti-shipping format. Ju 188E-2 was a torpedo-bomber, and could carry two 800kg torpedoes under wing hardpoints. It was also equipped with the FuG sea-search radar, to scan for enemy vessels. Although the Ju 188 did see anti-shipping service, its effect was limited by its numbers – only just over a thousand were built, and many of those were used in tactical bombing and reconnaissance duties rather than naval attacks.

The target. Convoy PQ 17, sailing in June–July 1942, was a terrible example of how efficient German anti-shipping tactics could be. A combination of constant aerial and U-boat attacks sank 24 of the 35 merchant vessels.

The Luftwaffe was one of the most technologically innovative arms of service in the Wehrmacht (sometimes at its strategic expense), and this was no less true in its pursuit of decisive air-launched anti-shipping weapons. Paving the way for the future of guided weaponry were the Ruhrstahl/Kramer X-1 (Fritz X) and the Henschel Hs 293. Developed during 1942, the Fritz X was essentially a freefall bomb fitted with electromagnetically operated spoilers that could give the bomb directional guidance following its release at an altitude of around 6,000m. The flight of the bomb was controlled via radio signal from the deployment aircraft, the bombardier maintaining visual contact with the weapon via a Lotfe 7 bombsight.

The Fritz X was a signal leap forward in aerial weaponry, but it was surpassed in sophistication by the Hs 293. This consisted of a rocket-powered glide bomb which could be deployed against ship targets potentially up to 3km away, giving the weapon a genuine stand-off range. Once it was dropped from a bomber, the Hs 293’s rocket motor would ignite, pushing it to a maximum speed of 900km/h. A red flare on the rear of the bomb enabled the bombardier to maintain visual contact, and again the flight was radio controlled, via a small joystick.

The aircraft mainly responsible for using these weapons was the Dornier Do 217, a four-seat bomber that went into service with KG 40 and II./KG 2 in the summer of 1941. The Do 217 offered decent speed (515km/h) and a useful maximum range of 2,200km. When fitted with an anti-shipping conversion kit, the Do 217 was a formidable prospect for Allied shipping, and particularly so when III./KG 100 began to deploy the guided weapons in the Mediterranean in August 1943. On 27 August, Do 217s sank the destroyer HMCS Athabaskan and the corvette HMS Egret in the Bay of Biscay. Two weeks late, on 9 September, the Fritz X/Do 217 combination scored even greater successes by sinking the Italian battleship Roma and damaging its sister ship, Italia. The British battleship Warspite was also put out of action by a Fritz X on 16 September. Other victims of the Fritz X were the US light cruiser Savannah and the light cruiser HMS Uganda. Numerous other ships were either damaged or sunk by the Hs 293, although the crew deploying this weapon struggled against the fact that the aircraft had to fly straight and level during the bomb’s flight to the target, a period that naturally caused problems in attracting AA fire or evading enemy fighters.

The guided weapons were impressive and groundbreaking, but they were no universal solution to Germany’s anti-shipping war. In the late summer of 1943, for example, several of the late-model Fw 200 C-6s in III./KG 40 were also being converted to launch this new weapon. Until they were ready, the He 177 was used in their stead. Fliegerführer Atlantik decided to send 25 He 177s from II./KG 40 against convoy MKS 30 on 21 November, hoping to achieve a major success with a massed attack. The He 177s launched a total of 40 Hs 293s against the convoy, but only sank one freighter and damaged another at the cost of three He 177s lost. On 26 November, II./KG 40 tried another mission against a convoy sighted off Algeria and succeeded in hitting the troopship Rohna with an Hs 293. Rohna sank with the loss of 1,138 lives – mostly US Army troops. Although this attack demonstrated the potential of the Hs 293 in standoff attacks, the He 177 proved vulnerable to interception and II./KG 40 lost 12 of its 47 He 177s in November 1943.

On 11 July 1943, a group of Allied ships heading south was detected about 480km off the Portuguese coast. This was a special convoy known as ‘Faith’, consisting of three large troopships escorted by two destroyers and a frigate. Three Condors attacked from medium altitude and this time achieved spectacular results with the Lotfe 7D bombsight. Both the 16,792-tonne SS California and the 20,021-tonne Duchess of York were hit and set on fire and were soon abandoned. The attack killed more than 100 personnel aboard these two ships but 1,500 survivors were taken on board the remaining troopship, SS Port Fairy, which set off towards Gibraltar escorted by a single frigate. Two Condors spotted the Port Fairy and succeeded in hitting this ship as well before being driven off by two US Navy PBY Catalinas from Gibraltar. The attack on ‘Faith’ was a shock to the British since the Condor threat was no longer regarded as significant by mid-1943. Furthermore, the success of medium-altitude bombing with the Lotfe 7D emboldened KG 40 to renew attacks on larger convoys.

As with the U-boat war, by the end of 1943 the Luftwaffe’s anti-shipping efforts were starting to become more a matter of survival rather than a strategically significant offensive, even with the introduction of the precision-guided bombs. The destruction visited upon the Allies had certainly been significant. During the period June 1940 to September 1943, for example, the Fw 200s of KG 40 alone sank a total of 93 ships of 433,447 tonnes and damaged a further 70 ships of 353,752 tonnes, and these figures were less than one-quarter of all Allied merchant tonnage sunk by German air attacks. While the actual physical damage accomplished by the Fw 200s was fairly minor, the psychological impact of successful air attacks in areas where the British did not expect them – west of Ireland and off the Portuguese coast – was such as to cause the Admiralty great anxiety. The vulnerability of convoys to the low-level attacks of the Fw 200 in 1940 was particularly unnerving to the British, and following the sinking of the Empress of Britain, Churchill became actively involved. German propaganda, which greatly exaggerated the success of the Condor attacks, further pushed the British prime minister to demand immediate action to counteract the threat posed by KG 40. Churchill, given the feebleness of Britain’s overall military position in the winter of 1940–41 and his inclination to strike back whenever possible, pushed both the Admiralty and the RAF to devote disproportionate resources to deal with the Condor threat, despite the fact that it was the shorter-range Ju 88s and He 111s that were doing the most damage to Allied shipping, if we look across all the theatres.

The pilot and observer of a German floatplane stare forward across the engine cowling of their aircraft. The Luftwaffe’s various biplane maritime reconnaissance aircraft were invaluable eyes and ears over contested waters, but production of the aircraft tended to be sidelined by combat aircraft.

The maritime Luftwaffe began to run up against a formidable strengthening of Allied defences as the war went on, resulting in an escalating attrition from 1942 onwards. Again, the experience of the Condor formations is instructive. By way of comparison, British defences against the Condor in the period 1940–43 saw 45 Condors destroyed in the air and on the ground, although AA and fighter damage probably contributed to the loss of a number of other Fw 200s over water. Surprisingly, the biggest eliminator of Condors was AA fire from the ubiquitous Defensively Equipped Merchant Ships (DEMS), which destroyed nine Fw 200s. In comparison, AA fire from Allied warships escorting the convoys only shot down four Condors with any certainty. Fleet Air Arm (FAA) fighters from escort carriers claimed five Condors in 1941–43 and RAF fighters from Catapult Aircraft Merchantmen (CAM) ships claimed another three. Land-based aircraft succeeded in intercepting at least 15 Condors, including eight by RAF Coastal Command and seven by the USAAF. In 1940, British convoy defences were unable to shoot down any Condors, but by 1941 about half the convoys that were attacked were able to damage or shoot down at least one Fw 200. Attrition came from other causes. In addition to a significant number of crashes during take-off and landing, many Condors and other aircraft simply disappeared over hostile seas, the fate of their crews unknown.

A side view of the enormous Bv 138 flying-boat. The bow and stern turrets each held a 20mm MG151 cannon, and the aircraft had two other machine guns as defensive armament.

This view of the Bv 222 shows the power needed to haul the huge aircraft and its load into the air. It was fitted with no fewer than six Jumo 207C inline diesel engines, each generating 1,000hp.

By mid-1944, German aircraft production had largely switched away from maritime aircraft, in favour of fighter and ground-attack aircraft. Furthermore, once the Allies had taken much of the French coastline following the D-Day landings, and had gained undoubted air superiority over Western Europe and the Mediterranean, the anti-shipping formations lost much of their rationale. Operations still continued over the Baltic against the Soviet forces. (The maritime formation covering the Black Sea – Seefliegerführer Schwarzes Meer – was disbanded in September 1944.) Yet with so few aircraft, and such mighty enemies, the Luftwaffe’s maritime force could do little to change the war’s outcome.

German paratroopers relax after their groundbreaking victory at the Belgian fortress of Eben Emael. Note the cut-down para helmets; the shape was designed to prevent the rim of the helmet snagging on ripcords and parachute lines during a drop.