The Luftwaffe was a vast and sprawling organization, its growth fuelled by the ambition and possessive character of its chief, Hermann Göring. One distinctive structural feature of the Luftwaffe was its inclusion of a substantial ground forces element, ranging from AA personnel to frontline combat units. As we shall see, quality and quantity were not always in a harmonious relationship in these units. The Fallschirmjäger paratroopers, for example, were a true elite amongst German forces, sent to the toughest parts of the front on account of their combat skills and tenacious nature. Many of the Luftwaffe’s field divisions, by contrast, gained a reputation for being virtual cannon fodder, and were hence incorporated into the Army in 1943. Göring’s vision of having his own personal army was imperfectly realized.

The fact remains that the Luftwaffe did make a significant contribution to the war on the ground. Even if such troops could not make a difference to the outcome of the war, they were nevertheless pioneers in many aspects of tactical warfare, particularly in terms of AA control and airborne warfare. They, therefore, deserve their mention alongside the pilots and aircrew who flew above them. (Note that more extensive discussion of German paratroopers is included in the companion volume to this book, Hitler’s Armies: A History of the German War Machine 1939–45, Osprey, 2011, also by Chris McNab.)

The idea of airborne troops is far from new, and dates back at least to the ancient Greek legend of the warrior Bellerophon riding into battle on the winged horse Pegasus. Even parachutes, as toys modelled on parasols, have existed for centuries, but it was not until the late 19th century that the idea of a parachute without a rigid framework evolved. World War I brought the concept to maturity as a life-saving device, first for observation balloon crews and then for those of heavier-than-air machines. Early types were of the static line variety, in which a rope attached to the aircraft pulls the parachute out of its container. The ripcord, which proved a major benefit for pilots and other aircrew, was not invented until 1919. However, the static-line variety came back into its own when the concept of parachute troopers began to mature.

The first serious parachute experiments were conducted by the Russians and Italians. Many German observers were interested, even excited, but, bound by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, they were forced to dream. However, when Adolf Hitler was confirmed as Chancellor, the dreamers and schemers began to work more openly towards their goals. Once he repudiated the hated Versailles Treaty and re-introduced conscription, all restrictions on their ambitions were removed, and few men were more ambitious than Hermann Göring, who quickly rose to command the reconstituted Luftwaffe.

Paratroopers exit from the side door of a Ju 52 aircraft. The static line has just reached full stretch and the parachute pack of the lower figure, falling in the recommended spread-eagle posture, is just coming open while a second man vaults from the Ju 52’s door.

Fallschirmjäger, 1940, showing typical kit and equipment. 1) Helmet showing liner with straps. 2) Parachutist’s jump badge. 3) Zeiss binoculars. 4) MP40 sub-machine gun. 5) Leather MP40 magazine pouches. 6) Leather map case with stitched-on pockets for pencils, ruler and compasses. 7) Water bottle and drinking cup. 8) Front and rear views of the external knee pads. 9) Luger holster. 10) First pattern side-lacing jump boots showing cleated sole. (Velimir Vuksic © Osprey Publishing)

Fi 156C-3 ‘DO+AI’ of Stab JG 27, Quotaifiya, July 1942. Another Geschwaderstab runabout to make it to Africa was this tan-camouflaged Storch, complete with Mediterranean theatre markings and Oberstleutnant Woldenga’s recently introduced Geschwader badge. Hardly in the ‘luxury’ class, Fi 156 Wk-Nr. 5407 was a true maid-of-all-work, not only undertaking vital communications and liaison duties, but also retrieving downed pilots from the tractless wastes of the Libyan and Egyptian deserts. (John Weal © Osprey Publishing)

Göring had been amongst those who watched Russian paratroop demonstration exercises in 1931 and 1935, and he had been so impressed that he now decided to begin construction of a German parachute corps. He already had a tiny nucleus of paratroops in the former Prussian Police Regiment ‘General Göring’, and in October 1936 he arranged a demonstration jump to encourage volunteers to form a parachute rifle battalion within this regiment. Although the demonstration was inauspicious, since one of the 36 jumpers injured himself on landing and had to be carried off on a stretcher, Göring soon had the necessary 600 recruits for his battalion. In 1938 the battalion – redesignated I. Btl/Fallschirmjäger Regiment 1 (FJR 1) – was transferred to the embryonic 7. Flieger Division. Further expansion was steady and, by the time general mobilization for war was ordered in August 1939, the Luftwaffe had two full parachute rifle battalions with support troops as the nucleus of this first German airborne division. In the meantime, the Army converted a standard infantry division into an air-transportable formation, the 22. Luftlande Division.

Wehrmacht airborne units were collectively known as Fallschirm- und Luftlandetruppen (parachute and air-landing troops); the Fallschirmtruppen were assigned to the Luftwaffe and the Luftlandetruppen to the Heer (Army). Within the Fallschirmjäger Division (parachute rifle division) only the three parachute infantry regiments were designated Fallschirmjäger; all other units were prefixed with Fallschirm- (parachute-). All units were parachute-trained and could also be landed by glider if necessary. One German unit was specifically glider-trained – Luftlandesturm Regiment 1 (1st Air-Landing Assault Regiment), but it was also parachute-trained. The Army converted two infantry divisions into air-landing units, 22. and 91. Infanterie (Luftland) Divisionen. Later in the war numerous Luftwaffe ground combat units were designated Fallschirm- for reasons of prestige, but few of the troops were by then in fact parachute-trained.

The difference between paratroops (Fallschirmtruppen) and air-landing troops (Luftlandetruppen) is straightforward. The former were trained to jump by parachute or land by glider to seize important tactical objectives, such as airfields or bridges, ahead of advancing ground forces, holding them until relieved. Paratroops are classed as light infantry (Jäger) and do not have much in the way of heavy weapons nor an inexhaustible supply of ammunition, so relief must be swift. Enter the air-landing soldier, flown with heavier equipment in transport aircraft such as the Junkers Ju 52, to land on ground already seized by the paratroops and deploy rapidly in their support. Prior to the almost total success of paratroop and air-landing operations in April and May 1940, however, there was considerable disagreement between the Luftwaffe and the Army as to how the new airborne forces should best be deployed. Generally speaking, the air force pundits thought they should merely be used in relatively small numbers as saboteurs to disrupt enemy lines of communication, spread panic and delay the arrival of reserves at the front. Many Army officers, on the other hand, believed in their employment en masse to create an instant bridgehead in a location the enemy would not be expecting. In the end, of course, both tactics would be employed during the war, proving only that each side was equally right. FJR 2 was organized in August 1939, and FJR 3 in July 1940, but thereafter no more regiments were to be raised until 1942.

Paras in Belgium consult a map before operations in May 1940. This photo was taken during the heyday of the Fallschirmjäger’s reputation, before the unacceptable level of losses endured during the invasion of Crete.

It is interesting to note how the Germans employed parachute units in their 1940 operations. In Norway in April 1940, a single company was dropped to establish a road block. In the same month in Denmark, three company drops were executed, to secure two airfields and a bridge, while in May a company was dropped piecemeal into far northern Norway over 11 days to reinforce beleaguered mountain troops. On 10 May 1940, in Belgium and the Netherlands, much more ambitious operations were undertaken: two regiments conducted multiple jumps ranging from platoon to battalion size. All of these operations – conducted in concert with the Luftlande Division, which air-landed troops by transports and even by seaplanes landing on a river – had the aim of seizing bridges and airfields. Furthermore, all were successful, and consequently the Allies received an abrupt lesson in the viability of airborne troops. Amongst all the achievements of the Fallschirmtruppen during the invasions of Belgium and Holland, the capture of the Belgian fortress of Eben Emael stands out most. The immense concrete and steel fortress of Eben Emael dominated the Albert Canal, the roads leading west from Maastricht and crucial bridges at Kanne, Vroenhoven and Veldwezelt. Eben Emael had 17 gun casemates that would have inflicted a heavy toll on conventional troops, but the bridges were essential to the German Army’s speedy advance, so they had to be captured and the fortress put out of action. The big question was ‘How?’ Against initial disbelief and hostility from the Army, General Kurt Student, the commander of 7. Flieger Division, won acceptance of his idea of using a specially trained assault force landed by glider on top of the supposedly impregnable obstacle. Gliders were chosen instead of parachutes because they could be landed more accurately and because the assault force would need cumbersome equipment, including flamethrowers, demolition charges and scaling ladders.

A Ju 52 flies in supplies for ground forces in the midst of a Russian winter. While the Luftwaffe’s supply capabilities were impressive, they still couldn’t meet the sheer scale of demand on the Eastern Front, as was proved during the Stalingrad defeat of 1942–43.

A unit of German paras at Eben Emael are attacking an embrasure of the Mi-Nord machine gun casemate; they have already blinded the Eben 2 armoured cupola on the roof (1) with a 1kg charge jammed into a periscope housing, and have killed its crew with a 50kg hollow charge – the first-ever combat use of such a weapon. They proceeded to blow one embrasure with a 12.5kg charge (2); now Feldwebel Wenzel (3), the commander of Truppe 4, and one of his men have rigged another (roughly hemispherical) 50kg charge over a second embrasure, while another paratrooper (4) sticks a smoke candle into a third. ‘Granit’ knocked out the fort’s key weapons within half an hour, and bottled up the rest of the defenders impotently, for a loss of only six Germans killed and 18 wounded. (Peter Dennis © Osprey Publishing)

In November 1939 the men who were to spearhead the invasion of Belgium began assembling in great secrecy at Hildesheim. They formed Sturmabteilung ‘Koch’, led by Hauptmann Walter Koch, comprising 11 officers and 427 men from I. and II./FJR 1. The group chosen for the attack on the fortress itself consisted of the 85 men of Oberleutnant Rudolf Witzig’s Fallschirmpionier Kompanie, given the codename Sturmgruppe ‘Granit’. All leave was cancelled and the group spent the best part of six months rehearsing its role, studying maps, a relief model and intelligence reports of interviews with disenchanted Belgian labourers who had worked on Eben Emael’s construction. Finally, all was ready and the men of the Sturmabteilung assembled at Köln-Ostheim and Köln-Butzweilerhof airfields during the afternoon of 9 May 1941.

Witzig’s Sturmgruppe ‘Granit’ had been allocated 11 DFS 230 gliders, which took off behind their Ju 52 towing aircraft at 0430hrs next morning. The gliders were released short of the Belgian border to glide the last 32km silently; the sun rising behind them making visual detection difficult. The Army’s main ground assault across the border was scheduled to begin five minutes after the gliders had landed to avoid alerting the defenders. Unfortunately, the tow ropes of two of the gliders, including Witzig’s, parted shortly after take-off so only nine landed on the fortress, which was shrouded in early morning mist. Temporary command was assumed by Oberfeldwebel Helmut Wenzel. Surprise was virtually complete, and although a few alert Belgian AA machine-gunners opened fire as the gliders came in to land, there was no real opposition until shells from field artillery deployed west of the fortress began to descend on the plateau. The Belgians had not thought to protect Eben Emael against assault from the air, so there were no upright stakes to rip into the gliders, no barbed wire, no minefields and no infantry defences for the gun positions.

Given that the Belgians were unprepared and taken by surprise; that they were understrength because their commanding officer, Major Jottrand, had sent many men on leave while others were billeted in nearby villages; and that they were low-grade static troops with no stomach for a firefight outside the security of their concrete walls, it is little wonder that the assault succeeded, even though the Fallschirmtruppen were outnumbered ten to one. Nine gun installations were put out of action within the first ten minutes, while two turned out to be dummies that consumed precious time. By nightfall the Jäger had control of the ground and dropped demolition charges down the lift shafts to prevent the garrison launching a sortie against them. At 0700hrs next morning they were relieved by the Army’s 51. Pionier Bataillon, which crossed the Albert Canal in assault boats, and shortly afterwards Major Jottrand raised a white flag. Casualties were incredibly light. Five men were injured during the landing, 15 wounded and six killed. Witzig, who had resumed command of the operation at 0830hrs on the morning of the attack after securing a second tow for his glider, was amongst those involved who were personally awarded the Ritterkreuz (Knights Cross) by Hitler.

German paratroopers spill from the back of a Ju 52 transport aircraft during the assault on Crete in May 1941. The design of the parachutes meant that they had little control over the descent trajectory and point of landing, resulting in many impact injuries on Crete’s rocky surface.

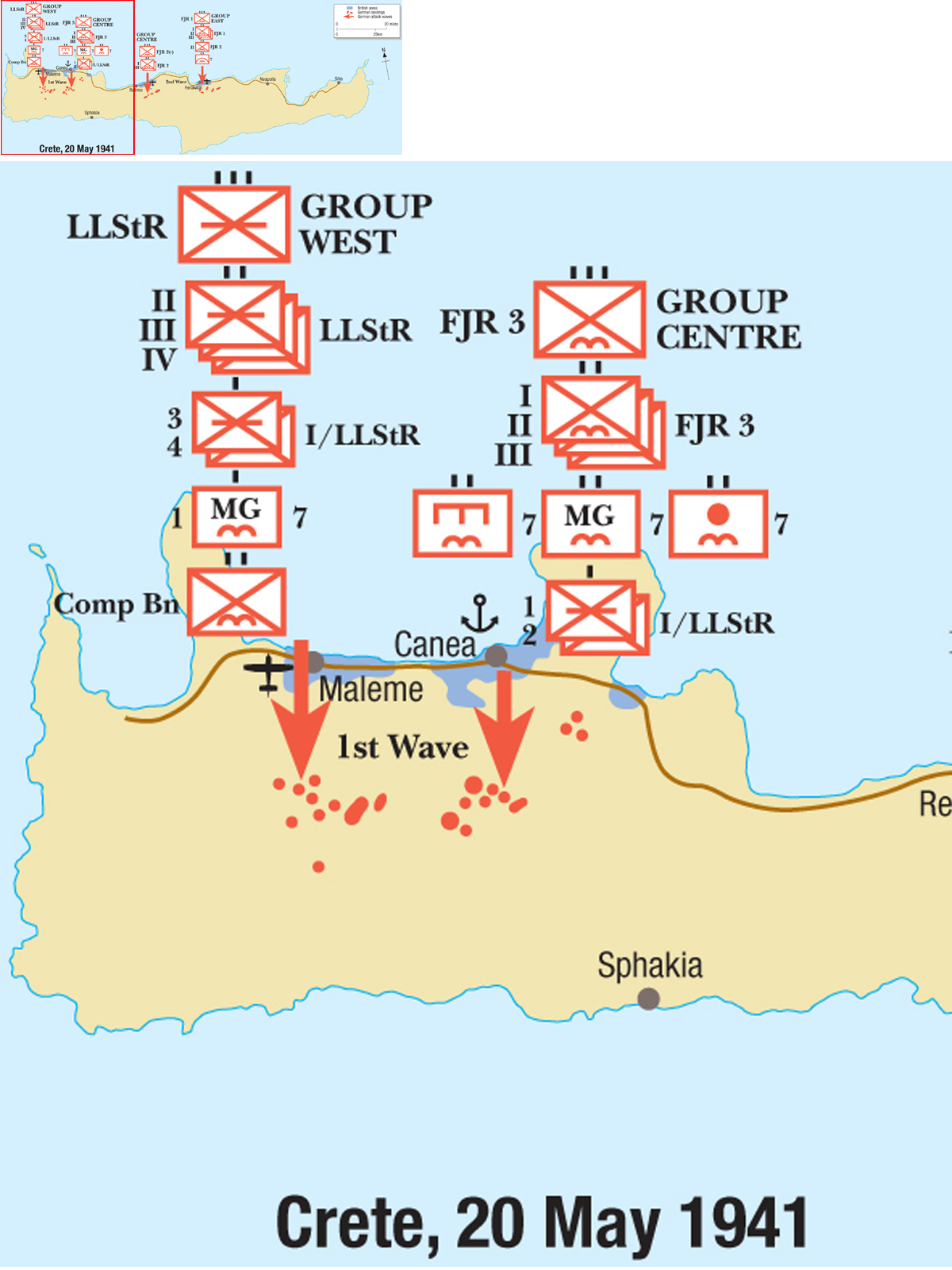

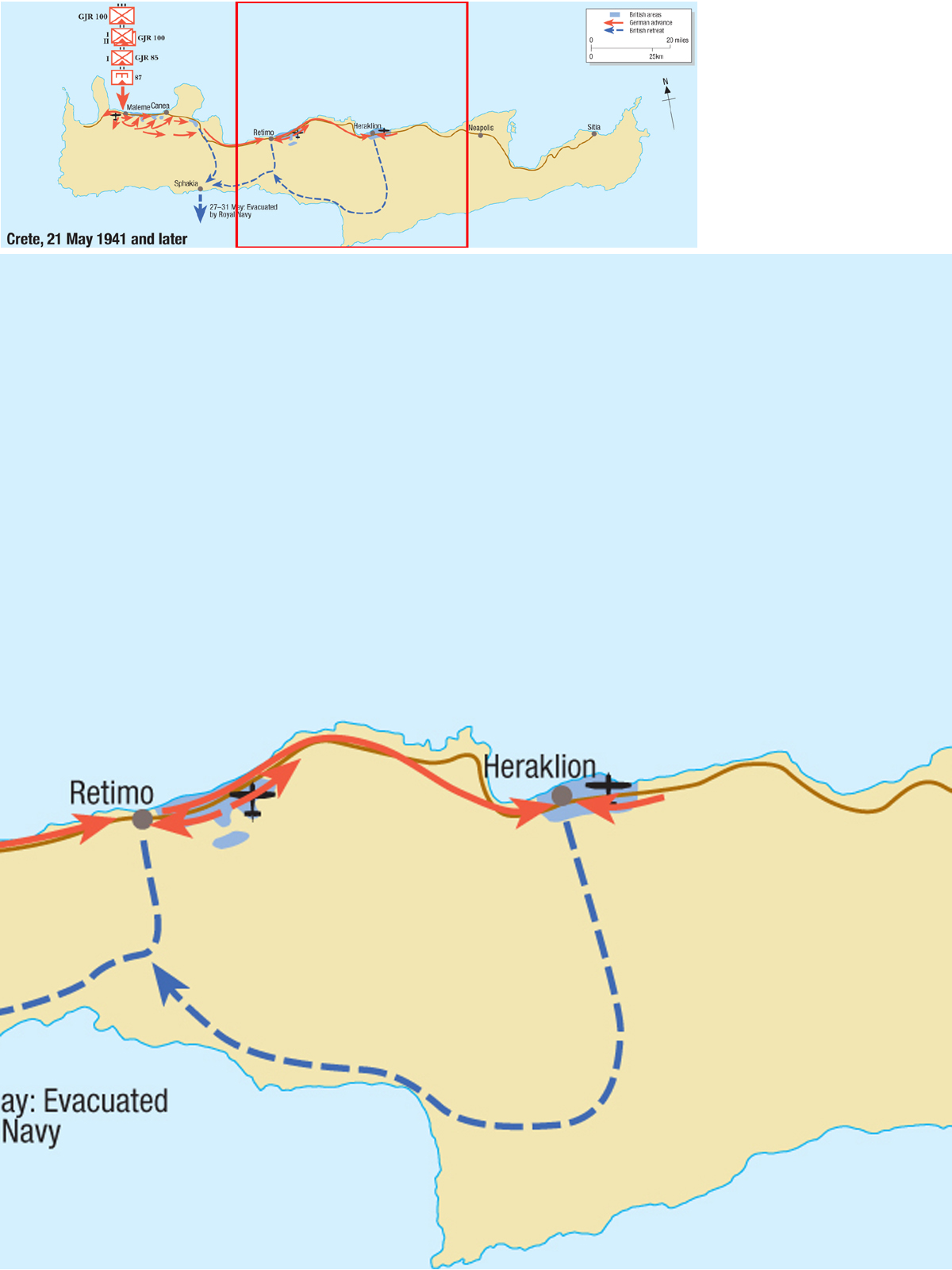

Eben Emael woke Hitler, and the world, to the emerging potential of airborne forces, and it is no wonder that commanders started to think in bigger terms. The Germans attempted more ambitious airborne operations with the invasion of Crete on 20 May 1941 which involved the airborne troops of General Student’s XI Fliegerkorps, formed on 1 January 1941. Operation Merkur (Mercury) began on 20 May with glider and parachute landings from a fleet of 500 transport aircraft. The British had failed to defend the island during a six-month occupation and most of the 35,000 garrison, commanded by the New Zealand World War I hero Lieutenant-General Bernard Freyberg VC, had just escaped from Greece with nothing but their own light weapons. The first assault of 3,000 paratroopers failed to capture the main objective, the airfield at Maleme, but after the New Zealanders withdrew from one end during the night the Germans began the next day to land reinforcements, despite still being under intense artillery and mortar fire. Whole units were wiped out before landing, or soon after, before they could reach their weapons, and the Royal Navy prevented a supplementary seaborne landing on the second night. Nevertheless, the Germans were able to land a steady stream of reinforcements and after a week of bitter fighting Freyberg ordered a retreat and evacuation.

Maps showing the invasion of Crete, May 1941. (© Osprey Publishing)

A ‘stick’ of paras drop over Crete in May 1941. The aim of the deployment was to drop the paras in close patterns, but many drops resulted in the soldiers being scattered over a wide area. A number of men even fell into the sea and drowned, tangled up in their parachutes.

The airborne invasion of Crete was one of the most spectacular and audacious events of the war, but it was also extremely costly. The Germans used the ‘ink spot’ concept of dropping numerous small units – battalions, companies, and even platoons – over a large area to seize several objectives. In contrast to normal German military doctrine, which emphasized the concentration of forces for the main effort (Schwerpunkt), this concept was more akin to Napoleon’s ‘engage the enemy everywhere and then decide what to do’. In Holland and Belgium this had been successful, since resistance was light and disorganized. It was another matter on Crete, where it cost the Fallschirmjäger dearly. Although the British Commonwealth defences were neither strong nor well organized, the Germans lost some 6,000 men, including aircrews. One out of five of the Fallschirmtruppen committed was killed – 3,764 – and some 350 aircraft were lost, including 152 valuable transports.

A column of German paratroopers moves along a road in Italy. The Fallschirmjäger extended their fame as an elite unit for their heroic defence at Monte Cassino in 1944, at which the Allies only managed to secure a Pyrrhic victory.

The Germans considered themselves lucky to have captured Crete, and Hitler was shocked by the losses. He concluded that the days of large-scale paratroop actions were over, and turned his parachute units into infantry regiments under overall operational command of the Army. The envisaged airborne assault on Malta was therefore cancelled because of fears of a repeat (a decision which had dire consequences for Axis logistics in North Africa, ravaged by British submarines and aircraft from that island). After Crete the Germans executed six parachute operations, but only one in more than battalion strength. The exception was on Sicily in July 1943, when FJR 3 and 4, a machine-gun battalion and a pioneer battalion were dropped in over four days as reinforcements. The other drops were essentially special operations: an attack on a now opposing Italian headquarters, seizures of two small islands, a raid on a Yugoslavian partisan headquarters, and a diversionary operation during the Ardennes offensive – of which the last two failed.

A paratrooper in the Ardennes in 1944 shows the advances of German infantry weapons since the beginning of the war. 1) FG42 assault rifle showing box magazine (1a) and spike bayonet (1b). 2) Infantry assault pack. 3) 15cm Panzerfaust 60. 4) 8.8cm RPzB 54 (Raketen Panzerbüchse [rocket anti-tank rifle] Modell 54) with rocket projectile (4a) (Velimir Vuksic © Osprey Publishing)

Regardless of Hitler’s dictate that the parachute troops would not again be employed in large-scale airborne operations, 7. Flieger Division was converted into 1. Fallschirmjäger Division (1. FJD) in May 1943, and 2. FJD had been activated in February. In October and November 1943, the 3. and 4. FJD were raised, to be followed by the 5., 6. and 7. in March, June and October 1944 respectively. The 7. FJD was formed from FJD Erdmann, an ad hoc formation of ‘alarm’ and training units. The original 2. FJD was destroyed in France in September 1944, and a new version was raised that December. Also in 1944, the headquarters of a 1st Parachute Army (1. Fallschirm Armee) was organized, to control I. and II. Fallschirm Armeekorps. This ‘parachute’ army and its subordinate corps were by no means true parachute formations, and neither was the so-called Fallschirm Panzerkorps ‘Hermann Göring’; none of these resoundingly titled formations had any parachute-trained units, and the ‘Fallschirm’ designation was given purely for morale purposes. By this time, even the parachute divisions were seriously short of qualified parachutists; of the 160,000 troops assigned to 1. Fallschirm Armee, in two corps and six divisions, only 30,000 were parachutists. Newly raised divisions were normally assigned a regiment, or one or two veteran battalions, from an existing division plus some school and demonstration troops as a cadre; the rest were non-parachute-trained recruits. Only a percentage of the men in even the cadre units were themselves parachute-qualified, and these were scattered throughout the formation rather than retained as a cohesive unit. It was for this reason that a partly parachute-qualified ad hoc battle group had to be assembled from both 1. FJD and FJR 6 for the 1944 Ardennes jump.

Regimental Staff

Infantry Battalion (×3)

Battalion Staff

Rifle Company (×3) (each 9× LMG, 3× 8cm mtr)

Machine Gun Company (8× HMG, 4× 8cm mtr, 2× 7.5cm gun)

Anti-Tank Company (3× 7.5cm AT gun, 27× 8.8cm bazooka)

Mortar Company (12× 12cm hvy mtr)

Pioneer Company

An artilleryman uses a rangefinder to guide the use of an 8.8cm Flak gun on the Eastern Front. The high muzzle velocity of the ‘88’ meant that it was as much suited to the anti-tank role as to its original anti-aircraft role.

The new Fallschirmjäger divisions were heavier, well supplied with support units, and better suited for the conventional ground combat to which they were committed. The 3. and 5.–8. FJD fought on the Western Front, 4. on the Southern, 9. on the Eastern, 1. on the Eastern and Southern, and 2. on all three fronts. From February 1942 to May 1943 Fallschirmjäger Brigade Ramcke, comprising battalions drawn from other formations, served in North Africa. As the war progressed, the divisions were provided with still heavier weapons, approaching those of an Army infantry division. For example, the original Fallschirm Artillerie Regiment possessed only one light battalion, but in May 1944 another light and a medium battalion were added, along with a heavy mortar battalion – although many such regiments remained understrength in practice. Anti-tank weapons were also increased.

A German MG42 paratrooper machine-gun team man a position in the ruins of Monte Cassino. Although the Allied artillery and bombers pounded the mountaintop monastery to pieces, this action actually made the German position more defensible.

Luftlandesturm Regiment 1 was absorbed into other units in 1943. Numbers of separate Fallschirmjäger regiments and battalions were raised, but they were eventually absorbed into new divisions. The 8., 9., and 10. FJD were ordered formed in September 1944, but were cancelled during their organization and their personnel were transferred to other divisions. The 11., 20. and 21. FJD began to form in March and April 1945, but were very far from complete by the end of the war in May.

Paratroopers seen during the Ardennes offensive of late 1944. The soldier on the left is carrying a British Sten sub-machine gun, and they are wearing a mix of para jump smocks.

This terse journey through the organizational lineage of the Fallschirmjäger can never do justice to the sheer bravery with which they fought, and the hardships they endured. The German paratroopers were frequently used in a ‘fire-fighting’ role, being rushed to the most contested parts of the line and, therefore, suffering an extremely high rate of attrition. Although Crete was their landmark airborne action, the Fallschirmjäger also raised their fame through equally epic ground battles. At Monte Cassino in January–May 1944, for example, Fallschirmjäger units fought against constant infantry attacks plus earth-shaking air and artillery bombardments for several months, helping to inflict more than 55,000 casualties on the Allies before the mountain fell. Although their original role was to be dropped by air into battle, the real value of the German airborne units lay in their high-level training, in their capabilities as combatants and in their very special esprit de corps.

Para recruits practise their landing rolls at the Stendal training centre. Recruits had to complete six training jumps before they were permitted to wear the coveted parachutist’s badge.

Luftwaffe field division troops in Stalingrad in 1942. Note that the soldier in the centre has an MP34 sub-machine gun; the regular Army’s standard sub-machine gun was the more modern (although certainly not better) MP38 or MP40.

The Fallschirmjäger were by no means the only ground forces fielded by the Luftwaffe during World War II. During the campaigns of 1940–41, many German AA units became de facto anti-tank units simply by depressing the muzzles of their 8.8cm guns to the horizontal. Luftwaffe ground crew and security staff also had frequent occasion to take responsibility for handling airbase attacks, particularly on the Eastern Front against partisans or other raiding parties. Göring, however – ever on the look-out for ways to expand his personal power – put forward a more formal proposition for Luftwaffe ground forces in late 1941, as Germany reeled from the sheer scale of its human losses against the Soviets. Hitler was convinced of the idea, and thus Göring scraped together enough men from throughout the Third Reich to form a total of seven Feldregimenter der Luftwaffe (Luftwaffe field regiments; FR der Lw), numbered 1–5 and 14 and 21. Each consisted of four battalions, each with three light companies and one heavy company, the latter including 8.8cm Flak guns.

The new field regiments were thrown into action piecemeal around the Eastern Front, and some appear to have fought with distinction. An OKW dispatch on 23 June 1941 stated that: ‘In the terrible winter battles on the Eastern Front, Luftwaffe field battalions in ground combat bravely defended the seriously threatened front lines. With units of the Army, these units are now involved in other operations.’

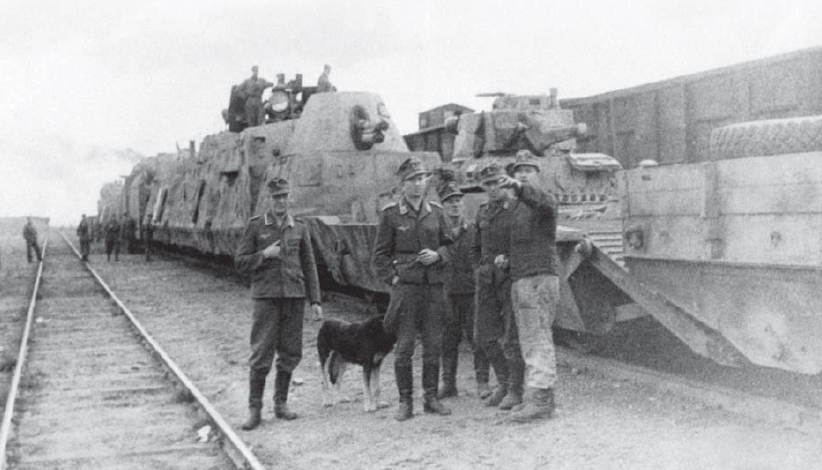

Luftwaffe field troops stand by the side of an armoured train on the Eastern Front. The soldiers who composed the field divisions were often drawn from the Luftwaffe’s rear echelon personnel, and they experienced a harsh induction to life in the frontline combat zone.

The quality of the Luftwaffe formations was nevertheless soon to be diluted. As the Army scoured Germany for new manpower, there arose the possibility of transferring surplus personnel out of the Luftwaffe into Army formations. For Göring, this threatened a weakening of his personal power, so instead he issued a call on 17 September 1942 for new Luftwaffe volunteers, who would form up into Luftwaffe field divisions (LwFD). Generalmajor Eugen Meindl was given the task of supervising the formation of 22 such divisions.

The manpower that went into forming the field divisions was often woefully unsuited to the cauldron in which they were to be thrown (the divisions were specifically intended for service on the Eastern Front). One member of 7. LwFD remembered his arrival at Mielau in the summer of 1942:

It took a long time until I found my unit. As I came from a heavy company I was assigned to an 88 mm section. But what horror! My comrades had no idea about weapons; even some of the officers didn’t … All these people were from different assignments – cooks, armourers, barbers, drivers, supply and administrative clerks, also men from the staff of the Luftgaukommandos. Some of them immediately requested to be returned to their original units. My commander told me ‘Please take over the training on the machine gun, because I have no idea about it!’ I was able to train for just three days – then we were shipped to Russia.

Recognizing the weaknesses of his new formations, on 12 October Göring issued Basic Order Number 3, which gave the order that the Luftwaffe units be deployed only to ‘defensive missions on quiet fronts’. The Reichsmarschall also requested that the Army accept the field divisions in a ‘comradely’ manner and assist with training, particularly in close combat skills and support weapons. The Luftwaffe divisions were supposed to be committed to combat as a single body and not to be separated without the approval of Army headquarters. The divisions fell under the tactical command of the Army while in the field, but remained under Luftwaffe control for personnel and administrative purposes. They were also significantly weaker in organization than equivalent Army formations. Whereas an Army division in 1942 had regiments of three battalions each and a full artillery regiment, the Luftwaffe field battalion had just four infantry battalions, plus an anti-tank and an artillery battalion. Weapons and equipment tended to be older and of inferior types, and vehicles were in limited supply.

The consequences of sending such ill-prepared and poorly equipped forces onto the Eastern Front were sadly predictable enough. Although some of the divisions received commendations for bravery, they also suffered extremely high casualties and performed badly at a tactical level. The fact that the creation of the Luftwaffe formations delayed the organization of four or five Panzer divisions with new vehicles, also annoyed the German Army High Command.

Luftwaffe field troops pose on a captured Soviet KV-1 heavy tank. Morale amongst the field divisions plunged as combat losses, poor equipment and scant training took a psychological and physical toll on the Eastern Front.

During the summer and early autumn of 1943, there was much debate about how to restructure the field divisions to improve their rock-bottom morale and make them into more efficient fighting units. The ultimate outcome was that in November 1943 the field divisions passed from Luftwaffe responsibility to Army authority, and were redesignated ‘Feld Division (Luftwaffe)’. Almost every Luftwaffe officer in the division was replaced by an Army equivalent, and in 1944 the divisions were structured along the same lines as their regular Army counterparts. These changes improved the combat capability of many of the formations, although inadequate training was to dog the personnel until the end of the war. Göring’s attempt to create his own formal land army had signally failed.

The Luftwaffe’s organizational scale meant that ground crew and specialist support personnel formed the overwhelming bulk of its activity. These personnel held numerous roles, from cooks to AA gun crews, and from veterinaries to drivers. Exploring each of these roles is beyond the remit of virtually any single-volume book, but here we will look at some of the core units and individuals who kept the Luftwaffe running.

In 1938 airfield ground crews became mobile Fliegerhorstkompanien (air station companies) each attached to, and named after, an individual Geschwader. In late 1943 a redesignation gave each its own number. The precise number of assigned Fliegertechnisches Personal (aircraft technicians) varied widely according to aircraft type and quantity, with additional administrative staff provided by the host Luftgau. Companies were divided into Züge, each of these platoons averaging 30 men under an Oberwerkmeister (line chief) and including airframe, engine and safety equipment fitters, armourers (ordnance and small arms), and instrument and radio mechanics. These were supported by a Werkstattzug (workshop platoon) under a Zugführer, with engine fitters, sheet metal workers, painters, harness repairers, carpenters, electricians and technical storemen, many of whom were Zivilpersonal (employed civilians).

A wounded soldier is carried aboard a Ju 52 casevac aircraft. The Luftwaffe actually pioneered long-range medical air transportation during the Spanish Civil War.

The twin-boom Gotha Go 244 was one of the more unusual transport aircraft of World War II. Within its rear storage compartment it could hold either 21 fully armed troops, a Kübelwagen car or assorted freight.

The airman of the Bodenpersonal (ground crews) was known by the nickname ‘Schwarzemann’ (‘black man’), inspired by the overalls he wore in Spain, and soon shortened to the affectionate ‘Schwarze’ (‘Blackie’). By the outbreak of war, he was in fact just as likely to be dressed in off-white or dark blue, but the old name stuck. Many of these men were drawn from civil engineering backgrounds or had trained in aircraft factories, and a high proportion were career NCOs. Working round the clock with minimal sleep, these unsung heroes were invariably the first to rise and the last to turn in. They served in all conditions from desert sands to Arctic tundra, and had to endure minimal quarters and comforts; their devoted work seldom brought them any official recognition, though they typically enjoyed a close relationship with their aircrew.

Their lot was aggravated by the unrelenting demands to maintain a viable air force despite worsening shortages of everything, and they performed minor miracles on a daily basis to keep their machines airworthy. Some ground crewmen had previously failed aircrew training; others longed to avenge the loss of loved ones in a more direct way. Aircrew shortages on multi-seat squadrons gave them the opportunity to volunteer for specialist training as stand-in gunners and flight engineers, and several gained combat sorties to their credit.

The acronym ‘Flak’ is derived from Flugabwehrartilleriekanone (flight defence artillery cannon), originally and correctly abbreviated to ‘FlAK’. Sharing the numeric designation of its parent Luftflotte, the largest formation was the Flakkorps comprising two or more Flakbrigaden or Flakdivisionen, according to requirements. The brigade, designated by Roman numerals, normally comprised at least two Arabic-numbered Flakregimenter, plus signal, supply and air units. While corps and brigade composition was flexible, that of the Flakregiment was fairly rigid, with an HQ staff and four Flakabteilungen (battalions) designated by Roman numerals (e.g., II./31 denoted II Abteilung of Flakregiment 31). First and second battalions were gun units, the third a searchlight (Höhenrichtkanone) unit, and the fourth a home-stationed Ersatz (replacement) training battalion. Abteilungen I, II and IV each contained three schwere (heavy) and two leicht (light) Flakbatterien. Heavy batteries usually consisted of 4 × 8.8cm guns, one predictor and two truck-mounted 20mm mobile defence guns. Light batteries comprised 12 × 20mm or 9 × 37mm guns, and up to 16 × 60cm searchlights. Batteries were numbered consecutively throughout the battalions: thus I Abteilung consisted of Batterien 1–5, II Abteilung of 6–10, III Abteilung of 11–13. The smallest operational unit was the Roman numbered Flakzug (platoon), with two heavy guns served by 14–20 men, three medium guns by 24 men or three light guns by 12 men.

An anti-aircraft gun crew man an 8.8cm Flak 36 in a static position. This type of gun became the cornerstone of the Luftwaffe’s ground defence of the Reich against the Allied strategic bombing campaign.

A German Flak team, seen here in Piraeus harbour, Greece, in 1941. Harbours were key targets for Allied bombing raids, thus they were often ringed with a mix of light (against low-level attacks) and heavy (medium–high altitude attacks) anti-aircraft guns.

A Luftwaffe Flak team stand by their gun in front of the Acropolis of Athens in May 1941. The largest of the German anti-aircraft weapons was the 12.8cm Flak, which could throw a 26kg shell to an altitude of 14,800m.

The Flakartillerie was consistently the largest arm of the service; in 1939 almost two-thirds of total Luftwaffe strength of 1.5 million – over 900,000 men – wore the scarlet Waffenfarbe of the Flak. By autumn 1944, when the Luftwaffe peaked at 2.5 million, the Flak had expanded to account for over half of that total. Apart from those units deployed to combat zones, a deep concentration of guns was established to protect German cities and industry from the relentless Allied air offensive; and from 1944 Allied attacks on European airfields brought all Flak personnel firmly into the front line of combat.

The outlandish Me 323 ‘Gigant’ (‘Giant’) was an enormous powered variant of the Me 321 glider. Its capacious interior was capable of holding more than 120 troops. Many of the 200 specimens produced were shot down over the Mediterranean theatre.

The Ju 52 was a true workhorse. It could carry either 17 passengers or 3 tonnes of freight. One of its key advantages was its ability to take off from short runways in adverse conditions.

The Junkers Ju 52 was the backbone of the Luftwaffe’s air transportation and supply capability. The tri-motor aircraft first flew in 1930, and was designed as a civilian transport aircraft and airliner, but in 1935 it was converted into a bomber/military transport for use within the nascent Luftwaffe (a rough bomb-bay conversion allowed it to carry up to 1,500kg of bombs). In this capacity the Ju 52 was first combat-tested in the Spanish Civil War, and was also used to conduct some bombing runs over Poland in 1939. However, thereafter it settled into two principal roles: transport aircraft and a means of deploying airborne troops, either by parachute or by air-landing. The Ju 52 had very limited performance characteristics. Its top speed was a mere 271km/h, and its service ceiling was 5,200m. Maximum range was less than 1,000km. If bounced by enemy fighters or caught in heavy AA fire, its chances of survival were limited. Yet the Ju 52’s virtue was its rugged reliability, plus its availability in reasonable numbers (more than 4,000 were built).

This branch had a pre-war strength of c. 100,000 men, and the composition of its elements was highly variable depending upon Luftflotte needs. Each fleet had three regiments (Luftnachrichtenregimenter) with anything from 1,500 to 9,000 personnel. The senior regiment shared the Flotte number, while the second and third added 10 and 20 to that figure respectively (e.g. Luftflotte 3 contained LNRegimenter 3, 13 & 23). Each regiment was commanded by a Höhere Nachrichtenführer (higher signals leader) with the rank of Oberstleutnant, and consisted of three to five Luftnachrichtenabteilungen – including one Ersatzabteilung – a battalion being commanded by a Major and his staff of 40–50 officers and men. A battalion averaged three to four (or rarely, up to 20) Luftnachrichtenkompanien, each under a Hauptmann. Each was permanently attached to, commanded by, and named after a combat Geschwader e.g. LN-Kompanie KG 77. The company was divided into three to six Luftnachrichtenzüge, each specializing in a particular discipline: telephone, teletype, cable-laying, construction, radio, battery-charging, vehicle maintenance, radio- and light-beacon platoons. Each Zug contained between five and ten Luftnachrichtentruppen, the basic operational unit, each of 10 to 20 men.

German officers pose happily in front of a Ju 52, as they prepare for deployment forward to the front line. In the Spanish Civil War and the early days of World War II, the Ju 52 also served as a basic medium bomber, although it was soon surpassed by other aircraft in this role.

Each Luftgau was assigned a Nachschubkompanie (supply company) comprising a Nachschubkolonnenstab (supply column staff), four Transportkolonnen (transport columns), and two or three Flugbetreibstoffkolonnen (aviation fuel columns). Companies had motor transport allotments of 50–100 vehicles, often supplemented with cars and trucks commandeered in occupied countries. Ground service and supply personnel had a combined pre-war strength of c. 80,000 men.

From February 1942 the increasing demands on manpower prompted the formation of various auxiliary units, thus releasing men for frontline service. Helferinnen (lit. ‘female helpers’) of the Luftnachrichten Helferinnenschaft (Air Signals Women’s Auxiliary Service) fulfilled mainly clerical and telephonic duties. Although not officially serving guns directly, Flakwaffenhelferinnen operated Scheinwerfer (searchlight), Horchgeräten (sound detection) and Richtgeräten (altitude prediction) equipment in flak units. Many received rudimentary instruction in gun crew tasks to enable them to give emergency assistance. Young male Flak-Helfer volunteers were drawn from the Hitler Youth, the Reichsarbeitsdienst (National Labour Service; RAD), and latterly direct from local schools. Over 75,000 schoolboys aged 15–16 operated Flakkanonen throughout Germany, their number bolstered by foreign volunteers and ex-POWs.

Established in 1935 from civilian fire service volunteers, the Fliegerhorst-Feuerwehr (Air Station Fire Defence; FhFw) was absorbed into the Luftwaffe in 1942. Service dress replaced their civilian uniform, but FhFw insignia were retained. A core staff of 14–18 men was established at each airfield with four to eight support personnel, assigned by daily roster, equipped and trained for fire-fighting. Although reclassified as Luftwaffemannschaften, they held Polizei status and were thus officially under the ultimate control of the Reichsführer-SS. In 1945 several Feuerwehrmänner equipped with Flammengewehre (flame-throwers) served as frontline assault teams during the battle for Berlin.

The Luftwaffe also had a direct or tangential connection to many aspects of Germany’s civil defence, particularly in terms of air raid responses. Definition of terms is important here: the German term ‘air protection’ (Luftschutz) covered not only air-raid precautions but also the fire service, bomb disposal, smoke screens, decoy sites and camouflage. The active measures – fighter aircraft, AA batteries, searchlights and balloon barrages – came under the heading of ‘air defence’.

The Reichsluftschutzbund (National Air Protection League; RLB) was founded in April 1933, to train all householders in domestic air-raid precautions. This pre-dated the revelation that Germany had an embryonic air force in defiance of the 1919 Versailles Treaty; in 1933 the RLM took effective control over all air protection and defence measures.

On 13 March 1935 it was announced that Göring had become the Air Minister and commander-in-chief of the new Luftwaffe, and a few months thereafter responsibility for air protection was taken over by the RLM. This responsibility was shared as follows: policy and national direction of operations lay with the Air Minister and the OKL; local services were organized as part of the Ordnungspolizei (Order Police), under the Reichsministerium des Innern (Ministry of the Interior; RMdI); and the RLB provided wardens and fire-watchers, and instructed the public. On 26 June 1935 the voluntary status of the RLB was cancelled, and it became obligatory for almost all able-bodied adults to play some part in air-raid precautions. (The membership of the RLB in 1938 was given as 12.6 million, and in April 1943 as 22 million.) Other government departments dealt with special aspects, e.g. the Reichswirtschaftsministerium (Ministry of Economics) through the National Group for Industry controlled industrial air-raid precautions; and the state-controlled services (railways, post office, inland waterways and national motor highways) had their independent organizations.

The RLM and OKL controlled operations at regional level and above: including most of the civil defence mobile reserve (SHD motorized battalions – see below), the Luftschutzwarndienst (Air Protection Warning Service; LSW – see below), shelter policy and lighting restrictions. The RMdI, through the police, controlled local SHD services in the towns – fire-fighting, rescue, first aid, veterinary services, and anti-gas measures – subject to policy dictated by Göring. Evacuation and post-raid services were the responsibility of the Nazi Party.

Luftwaffe gunners prepare 8.8cm Flak rounds for firing. By the end of the war, Flak crews in Germany were facing nightly dangers every bit as severe as those at the front lines of the fighting.

The German civil defence organization fell into five main divisions:

1 The national services organized and trained by the Luftwaffe. These comprised the Luftschutzwarndienst (Air Protection Warning Service; LSW), which tracked and reported raids in co-ordination with the police, and controlled public warnings; bomb-disposal units; smoke troops, decoy sites and target camouflage. From 1942 onwards the main air protection mobile reserve units – the former SHD motorized battalions – also became a national service and part of the Luftwaffe as the Luftschutz Abteilungen (mot) (motorized air protection battalions).

2 Local services organized and trained by the police: (a) warning services, and (b) from May 1942, the Luftschutzpolizei (Air Protection Police) – the former non-mobile SHD.

3 The Reichsluftschutzbund (National Air Protection League; RLB) was responsible for educating and training the public and providing wardens and fire-watchers. It embraced both the Selbschutz (Self-Protection Service) (for residential areas), and the Erweiterter-Selbschutz (Extended Self-Protection Service) (for business premises, institutions, places of entertainment, etc). It was not affiliated to the Party – although many of its prominent members were Nazi leaders – and kept clear of it until 1945. In March 1934 a law authorized the wearing of an RLB uniform.

Luftwaffe anti-aircraft units provide a demonstration of their weapons to factory workers. In the last months of the war, all manner of civilian volunteers might find themselves helping to operate or supply such weapons.

4 The services of major industrial concerns were organized and trained by the National Group for Industry under the Minister of Economics. Apart from the state-owned entities (see 5 below), industry as a whole was covered by the Werkluftschutzdienst (Factory Air Protection Service).

5 Railways, post office and inland waterways were self-contained, and each was responsible for organizing and training its own civil defence services, which followed the same pattern as for major industry. These came directly under the authority of Göring, and co-operated with the local services as required.

In operations within a town the police chief controlled entirely groups (2) and (3), and could call on groups (1), (4) and (5) for assistance.

In the early part of the war only two signals were used on LSW sirens – the ‘general alarm’ and the ‘all clear’. On the sounding of the general alarm all activity ceased, traffic stopped and industry halted.

As the frequency of raids increased changes became necessary to prevent loss of working hours. An elaborate system of confidential telephoned alerts to war industries, etc., gave 12-minute and six-minute warnings. Public warnings conveyed signals for ‘small raid possible’, ‘immediate danger’, ‘pre-all clear’ and ‘all clear’. Information on the movements of enemy aircraft and the progress of raids was also broadcast from the end of 1942 onwards. There were in all seven forms of warning, of which five were public. It was laid down that only on a warning of the approach of more than three aircraft flying in formation, or more than ten not in formation, were people to go to the shelters.

The Luftschutzpolizei was formed in spring 1942 from the former mobile battalions of the Sicherheits u. Hilfdienst (Security & Assistance Service; SHD). The SHD was formed in 1935 under police direction, as a civil defence service in 106 of the largest ‘first category’ towns and cities that were the most vulnerable to air raids. In 1940 a motorized SHD strategic reserve of three to four battalions was formed to provide reinforcement to towns under heavy attack; each town having an SHD transferred a quota of men to form the nucleus for these mobile battalions, which were self-supporting, well-equipped and capable of rapid transfer.

As a result of the first heavy attacks on Lübeck and Rostock in spring 1942 the air protection organization was overhauled; in April/May 1942 the SHD was renamed the Luftschutzpolizei, which provided the following local services: fire-fighting and decontamination; rescue and repair; first aid posts, first aid parties and ambulances; veterinary services, and gas detection services. The administration and training of the Luftschutzpolizei remained under the Ordnungspolizei, although Göring was responsible operationally for this, as for all other air protection services. The number of air protection police officers allotted to a town was roughly in proportion to the population. The personnel were under police discipline, lived in barracks, and wore a uniform similar to that of the Luftwaffe but with distinctive police-style insignia. It should be noted that the voluntary technical services – Technische Nothilfe (TeNo), the Todt Organization, the Evacuation Police, etc. – were not part of the Luftschutzpolizei, although they co-operated closely with it.

The mobile reserve battalions of the former SHD were transferred to the Luftwaffe and renamed Luftschutz Abteilungen (mot); the number of battalions was also greatly increased. Their activities were mainly confined to fire-fighting, rescue and debris-clearance duties, with some decontamination and first aid work. They thus became part of the national rather than local services.

The Luftschutzgesetz (Air Protection Law) of 26 June 1935 made participation in air-raid precautions compulsory for practically all able-bodied Germans. On 4 May 1937 a decree in application of this law laid down the services to be performed, the procedure for conscripting personnel, and the conditions of service.

The Selbschutz formed the first line of domestic defence against air raids. Its main functions were the equipping of communal cellar shelters and the performance of fire-watching duties under the direction of the house warden, under the operational orders of the chief of the police precinct. The squads were trained, organized and led into action by the block warden, while the individual fire-watchers were controlled by the house warden – who was frequently a woman. In large ‘first category’ towns the Luftschutzpolizei were available to reinforce the Selbschutz at any incident beyond its control. The organization had no obligation to report an incident immediately unless it was beyond their capabilities. In small towns and rural communities the service formed an ‘air protection fellowship’; these, the Feuerwehren (volunteer fire brigades), and – for rescue duties – local personnel provided by the Technische Nothilfe, were the sole forces immediately available. Help could be sent from the nearest town when necessary. Members of the Selbschutz were expected to supply their own clothing and equipment other than a respirator and steel helmet.

The 8.8cm Flak gun, operating in its traditional anti-aircraft role. The Flak 18 gun had a maximum ceiling of 18,000m, firing its shells at a muzzle velocity of 820m/sec.

This service was established to cover those institutions, government offices, hotels and other communal buildings not large or important enough to the war effort to have a Factory Air Protection Service. Known as the Erweiterter-Selbschutz, it was administered and operated similarly to the Selbschutz, but with certain additional features, i.e. a leader-in-charge, control room for the premises, and simple rescue and first-aid equipment. Shelters had to be provided for employees. Training of leaders was carried out by the police, and the leaders in turn trained their personnel. All other members forming the reserve groups were trained by RLB wardens on payment of the appropriate fees to the League.

Fallschirmjäger gather around the wing of their Ju 52 drop aircraft, and study a map of their intended landing zone. The Ju 52 was a mixed blessing for paratroopers; it was sturdy and reliable, but was vulnerable to enemy fighters and anti-aircraft fire.

For the supervision of war production as well as air-raid protection, Germany was divided into industrial divisions, in each of which an Air Protection Leader was appointed; the division was sub-divided into regions, districts or smaller segments, each with an appointed leader. This service provided a rapid channel for information to each factory.

The Werkluftschutzdienst (Factory Air Protection Service) organization within an industrial concern resembled that of the local authority service (air protection leader, control room, fire-watchers, fire-fighting, decontamination and first aid squads, and – where a factory used animals – a veterinary section). The personnel were recruited from employees by the air protection leader, who himself was appointed by the police. The works leader could, in case of emergency, call upon all persons within his sphere of responsibility or those in the vicinity to give temporary assistance to his squads. There were limitations on the number of times certain classes and age groups could be required to do duty in any one month. In many cases women employees were required to serve in all capacities. Those factories employing more than 100 people had to provide strong and mechanically ventilated shelters, which were subject to regular inspection. When the tempo of raids increased the types of shelters had to be revised, some factories going so far as to construct the multi-storied ‘bunker’ type. Training for key factory air protection personnel was given in a chain of independent schools, these leaders in turn training the factory employees.

If an incident in a factory was beyond the capabilities of the works squads and co-opted assistance, the local authority police president would be asked for help; in many cases the town fire and other services would anyway be sent to help immediately information of an incident was received. The factory fire brigade was also at the disposal of the police president, as this service was an official auxiliary unit of the town fire-fighting force.

Although not everyone involved in civil defence had a direct employment by the Luftwaffe, they nevertheless formed part of Germany’s total air defence response, and were coordinated at the highest levels by the Luftwaffe’s high command. This brief journey through the types of Luftwaffe personnel clearly illustrates that actual aircrew were merely the tip of a very long spear.

April 1945. The wreckage of German night-fighters litters an airfield in Germany. The aircraft were probably the victims of Allied ground-attack missions, which had virtually free run over much of Germany by this stage of the war.