THE QUALITIES OF LEADERSHIP

Dwight D. Eisenhower as Warrior and President

David M. Kennedy

FEW LEADERS ARE MEN FOR ALL SEASONS. THE QUALITIES THAT DEFINE an effective leader in one circumstance may be useless or even mischievous in another. Ulysses S. Grant provides a notorious example of this disjunction. Gloriously successful as a military commander, he was embarrassingly inept as president. His malfeasance in the White House mounted to such proportions that he formally apologized to his countrymen in his final State of the Union message. Americans took the point. They had elevated five generals to the presidency in the Republic’s first century.* They waited nearly another century before they so honored another professional soldier, Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Both Grant and Eisenhower were obscure Midwestern-bred career military officers, of modest achievement and unspectacular promise until war suddenly thrust great responsibilities, and opportunities, into their hands. Before he met Lee in triumph at Appomattox, Grant had tasted battle in Mexico, served a few routine tours of duty at desolate outposts, and resigned from the army out of boredom in 1854.

Like Grant’s, Eisenhower’s capacity for leadership long languished in latency. A fifty-one-year-old freshly commissioned brigadier general when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Eisenhower had yet to see combat. He had spent World War I training tank troops in a stateside camp, attended several advanced military colleges in the ensuing decade, and served on Douglas MacArthur’s staff in the Philippines in the 1930s. In December 1941 he was attached to Third Army headquarters in San Antonio, Texas, when Army Chief of Staff George C. Marshall summoned him to Washington to head the Pacific and Far Eastern Section of the War Department’s War Plans Division.

Marshall valued Eisenhower’s familiarity with the Far Eastern situation, particularly in the Philippines, but he wanted more than his subordinate’s regional expertise. Amid the chaos of war-girding Washington, Marshall needed assistants who would shoulder heavy responsibilities and act decisively without constantly coming to him for consultation. Eisenhower did not disappoint. Within hours of his arrival he drafted a plan to use Australia as a base of operations against the Philippines. Characteristically, he justified his proposal for swift and heavy military effort with an appeal to considerations of morale: “The people of China, of the Philippines, of the Dutch East Indies will be watching us. They may excuse failure but they will not excuse abandonment.”

Eisenhower’s next assignment was to draw up a letter of instruction for a still-unnamed “supreme commander” of American, British, Dutch, and Australian land, sea, and air forces in the western Pacific. This was a formidable task, envisaging the virtually unprecedented coordination of traditionally discrete services from several sovereign states. Eisenhower submitted his draft on December 26, 1941. He later noted in his diary that “the struggle to secure the adoption by all concerned of a common concept of strategical objectives is wearing me down. Everybody is too much engaged with small things of his own, or with some vague idea of larger political activity, to realize what we are doing, rather, not doing…. [W]hat a job to work with allies.”

Allies, Napoleon once said in exasperation, were his preferred enemies in war. Eisenhower at times shared the sentiment. Yet the ability to work productively with allies, however frustrating, proved to be Eisenhower’s special genius. In June 1942, Marshall sent him to England as the head of American forces in the European theater of operations. By the end of the year he was commander of the Allied expedition in North Africa. During the invasions of North Africa and Italy in 1942 and 1943, he developed a command structure that integrated the several services of various nationalities under three British subordinates directly responsible to him. Assembled in full uniform, Eisenhower’s biographer Stephen Ambrose wrote, these men “looked the personification of British tradition and habit of command.” They might have intimidated a Kansas boy on his first combat assignment, but Eisenhower determined “to work with them, not by imposing his will but through persuasion and cooperation.” By those means, Eisenhower demonstrated a remarkable capacity for coordinating British, American, and French air, naval, and ground forces. His reward came at Cairo on December 6, 1943, when President Roosevelt named Eisenhower supreme commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe, responsible for planning and executing the invasion of northwestern Europe that eventually took place in Normandy on D-day, June 6, 1944.

The Allies might have shared the common objective of defeating Hitler, but Eisenhower never took inter-Allied cooperation for granted. Indeed he considered its careful and deliberate cultivation to be among the highest priorities of his command. “The seeds for discord between ourselves and our British allies were sown,” he wrote to Marshall, “as far back as when we read our little red school history books. My method is to drag all these matters squarely into the open, discuss them frankly, and insist upon positive rather than negative action in furthering the purpose of Allied unity.”

Immediately on his arrival in England in June 1942, he ordered his staff to cultivate an attitude of enthusiasm and optimism. He specifically encouraged friendly relations with the British. Officers who publicly criticized the British he sent home. When General George Patton demanded an apology for British criticism of his corps, Eisenhower forcefully suppressed this call “for the last pound of flesh.” He would not tolerate “any criticism couched along nationalistic lines,” he admonished Patton, so that “every subordinate throughout the hierarchy of command will execute the orders he receives without even pausing to consider whether that order emanated from a British or American source.”

Eisenhower instinctively felt that the gossamer tissue of personal relationships counted for far more than the formal architecture of his table of organization in determining the success or failure of his command. “The problem of establishing unity in any allied command,” he explained to Lord Louis Mountbatten, “involves the human equation.” The British-American Combined Chiefs of Staff might issue carefully crafted written directives on the structure of an allied command, but the command’s “true basis lies in the earnest cooperation of the senior officers assigned to an allied theater. Since cooperation, in turn, implies such things as selflessness, devotion to a common cause, generosity in attitude, and mutual confidence, it is easy to see that actual unity in an allied command depends directly upon the individuals in the field…. Patience, tolerance, frankness, absolute honesty in all dealings, particularly with all persons of the opposite nationality, and firmness, are absolutely essential…. [T]he thing you must strive for is the utmost in mutual respect and confidence among the group of seniors making up the allied command [Eisenhower’s italics].”

Eisenhower practiced what he preached. No matter how wearing his duties or how grim the military outlook, by act of will Eisenhower as supreme commander “firmly determined that my mannerisms and speech in public would always reflect the cheerful certainty of victory.” His British colleague and sometime rival Bernard Montgomery conceded that Eisenhower’s “real strength lies in his human qualities…. He has the power of drawing the hearts of men towards him as a magnet attracts the bits of metal. He merely has to smile at you, and you trust him at once. He is the very incarnation of sincerity.” Omar Bradley noted more succinctly that Eisenhower’s smile was worth twenty divisions.

It would be mistaken to discount the importance of Allied unity in the winning of the war or to undervalue Eisenhower’s techniques of willed optimism and cultivated trust for achieving that unity. World War I, with its costly lack of liaison among national armies, as well as its protracted bickering about what use to make of American troops, provided an object lesson about the human toll that lack of concerted military effort could exact. The stakes were even higher in the vastly larger conflict of World War II, especially in the dauntingly complex operations that culminated in D-day and the race for the German frontier. One observer at a meeting before the Normandy invasion wrote that “it seemed to most of us that the proper meshing of so many gears would need nothing less than divine guidance.” Eisenhower’s guidance may not have been divine, but it was surely inspired. Most important, it worked, and historians rightly give him major credit for providing the kind of concerting leadership that ultimately crowned the Allied effort with success.

Eisenhower defined the ability to nurture optimism and elicit cooperation as the essence of leadership. He believed that such ability was not an innate but an acquired characteristic, the acquisition of which resulted from serious psychological study. “The one quality that can be developed by studious reflection and practice is the leadership of men,” he wrote to his son in 1943. “The idea is to get people working together, not only because you tell them to do so and enforce your orders but because they instinctively want to do it for you…. Essentially, you must be devoted to duty, sincere, fair and cheerful. You do not need to be a glad-hander nor [sic] a salesman, but your men must trust you and instinctively wish to win your approbation and to avoid things that call upon you for correction.” Conspicuously absent from this list of a military leader’s qualities was any mention of the need for aggressiveness or initiative, or steely resolve in the face of a threatening enemy, or any of the bravura theatrics or pugnacious posturing that one associates with figures like Douglas MacArthur and George Patton. Here, clearly, was no ordinary military commander.

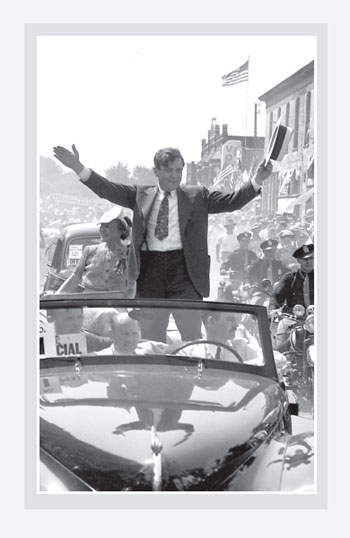

By war’s end Eisenhower had not only masterfully completed the acquisition and deployment of his chosen leadership techniques but succeeded in projecting their appeal to wide segments of the American public. Both political parties sought him as a presidential candidate. Americans might have been tired of war in the late 1940s, but they had not wearied of this war hero. Significantly, their high regard for Eisenhower rested on a perception that he was not in fact a “militaristic” personality, as Columbia University sociologist Robert Merton demonstrated in an analysis of some twenty thousand letters written to the general in 1948. Similarly, much of his later popularity in the nation’s highest political office owed to the notion that he was not an ordinary “politician.” Eisenhower, in short, had perfected the art of playing against his assigned role, first as a nonmilitary general and later as a nonpolitical president. This deliberately cultivated style had proved enormously successful in war. How would it work in the White House?

Among those urging a presidential candidacy on Eisenhower in the immediate postwar years was the former New York governor and two-time Republican presidential candidate Thomas E. Dewey. Visiting Eisenhower’s home in July 1949, Dewey outlined his reasons for wanting Eisenhower to run. The general, now president of Columbia University, reflected at length in his diary on the conversation with Dewey. He wrote:

The governor says that I am a public possession, that such standing as I have in the affections or respect of our citizenry is likewise public property. All of this, though, must be carefully guarded to use in the service of all the people…. The governor then gave me the reasons he believed that only I (if I should carefully preserve my assets) can save this country from going to hades in the handbasket of paternalism, socialism, dictatorship…. His basic reasoning is as follows: All middle-class citizens have a common belief that tendencies toward centralization and paternalism must be halted and reversed. [But] no one who voices these views can be elected…. Consequently, we must look around for someone of great popularity and who has not frittered away his political assets by taking positive stands against national planning, etc., etc.

Three years later this political strategy paid handsome returns, lifting Eisenhower to the presidency with one of the largest popular majorities in the century. Carefully striking a nonpartisan pose during his campaign, he entered office with his truly remarkable assets of public affection and respect fully intact. Those assets had been painstakingly accumulated and conscientiously conserved for more than a decade. Now, if ever, was the time to spend them.

OF ALL THE ISSUES confronting the new president in 1953, none seemed more appropriately to call for the investment of his great moral capital than the historically vexed problem of racial equality. Nearly a hundred years after Ulysses Grant had conquered the slave power on the battlefield and helped direct the reconstruction of the South as president, black Americans were still not fully free. Most still dwelled in the eleven states of the former Confederacy. There they attended segregated schools, held the least desirable jobs, and were denied all political power. Only about 20 percent of eligible southern blacks were registered to vote in the election that brought Eisenhower to the White House.

Yet the low number of southern black voters represented a dramatic improvement over the situation just ten years earlier, when only about 5 percent of eligible blacks were registered to cast ballots. Thanks to the Supreme Court’s 1944 decision in Smith v. Allwright, outlawing the restriction of Democratic Party membership to whites, and to the raised consciousness and rising militancy of returning black war veterans, the winds of change were beginning to sweep through the musty structure of race relations in the South. They gathered further force in 1954, when the Supreme Court declared in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that segregated schools were unconstitutional. But even then those winds were only beginning to stir. To become a real driving force or to avoid swelling to a destructive typhoon, wise leadership was needed.

For blacks and whites alike, the 1950s marked a moment when old patterns of thought and behavior started to swing loose from their traditional moorings, a moment when the culture’s official values of equality and fairness were thrust abrasively against the base realities of discrimination and prejudice. Alternatives to segregation now opened up. As the philosopher Sidney Hook observed in his study of the hero in history, “insofar as alternatives of action are open, or even conceived to be open—a need will be felt for a hero to initiate, organize, and lead.”

Psychological research has confirmed Hook’s intuitive insight. In experiments studying schoolchildren in new situations, they were found to be more susceptible to guidance “during the period of initial ambiguity.” The 1950s witnessed the first element of ambiguity in American race relations in nearly a century. It was an unusually opportune time for the effective exercise of leadership, a rare historical moment when the path lay open to what James MacGregor Burns has called “transforming leadership,” leadership that “can exploit conflict and tension within persons’ value structures” and lift them to higher levels of moral development.

Dwight Eisenhower, who had organized and led the Western Allies in the liberation of Europe from Nazism, was an authentic hero. Few figures could have been more fit to lead Americans out of their ancient enslavement to racism. To Eisenhower fell a unique opportunity to assert “transforming leadership.” That he did not grasp it constitutes perhaps the greatest failure of his presidency. It also raises questions about the particular qualities of leadership that Eisenhower embodied.

To be sure, Eisenhower had little personal taste for this task. He had grown up in an all-white town and served out his military career in a segregated army. As supreme commander in Europe he had allowed black troops to volunteer for combat duty during the sharp crisis of the Battle of the Bulge in late 1944 but swiftly returned them to their all-black noncombat units when the crisis passed. He had advised against integrating the armed forces in testimony to the Senate Armed Services Committee in 1948. During his presidential campaign in 1952 he had criticized Democratic proposals for a permanent Fair Employment Practices Commission to curb job discrimination by the federal government and government contractors. All his life he had lived, without evident discomfort to his conscience, under the segregationist regime sanctioned by the Supreme Court’s doctrine of separate but equal, enunciated in the notorious Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896.

Yet Eisenhower was no bigot. Though he shared many of the prejudices about African Americans common to his caste and generation, they were tempered by his authentic commitment to values of equality and fair play. He worked to end segregation in the District of Columbia and faithfully saw through to its completion President Truman’s program to desegregate the armed forces. He also moved to stop discrimination in several federally operated facilities in Virginia and South Carolina and to integrate schools at southern military bases.

But those measures marked the limits of Eisenhower’s disposition to alter the state of American race relations. When in 1953 South Carolina Governor James F. Byrnes expressed his fears about the impending Supreme Court decision that was to upset forever the separate but equal doctrine, Eisenhower reassured him that “improvement in race relations is one of those things that will be healthy and sound only if it starts locally. I do not believe that prejudices, even palpably unjustified prejudices, will succumb to compulsion.”

Events soon dramatically tested the viability of the sentiment. On May 17, 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down its epochal decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. The justices unanimously concluded that separate school facilities were inherently unequal, hence unconstitutional. The following year the Court ordered integration of the nation’s schools to proceed with “all deliberate speed.” This was the very development that Byrnes and other white southerners had anticipated and dreaded. They reacted in ways reminiscent of the era before the Civil War. The Alabama senate passed a resolution of “nullification,” and Virginia asserted its right “to interpose its sovereignty” against the Court’s decision. Virtually the entire southern congressional contingent in 1956 signed a “Southern Manifesto” announcing their intention to resist the Court’s order by all lawful means.

In the Brown decision the Court had sharply prodded the most conflict-laden issue in American life, the volatile truce between the black and white races as defined by the separate but equal formula in the Plessy case. Eisenhower accurately described the Brown decision as upsetting “the customs and convictions of at least two generations of Americans.” To reform those mores in this uniquely malleable moment was the challenge now facing him. Regrettably, he refused to accept it. Indeed, on the eve of the Supreme Court’s announcement, Eisenhower had spinelessly remarked to Attorney General Herbert Brownell that he hoped the justices “would defer it until the next Administration took over.”

Even before the official announcement of the Brown decision, Eisenhower thus began to chart a course of avoiding the race issue, a course to which he held throughout the remainder of his presidency. Despite repeated pleas from civil rights leaders, he resolutely refused to declare his approval of the Supreme Court’s ruling, claiming that “it makes no difference whether or not I endorse it” and that “if I should express, publicly, either approval or disapproval of a Supreme Court decision in one case, I would be obliged to do so in many, if not all, cases.”

He similarly refused, again ignoring the supplications of his sole black aide, publicly to condemn the murder of Emmett Till, a fourteen-year-old black Chicagoan whose mutilated body was found in a Mississippi river after he had allegedly “wolf-whistled” at a white woman. Nor did he protest when the University of Alabama defied a federal court order and expelled a black student, Autherine Lucy, on racial grounds. When at last in 1956 Eisenhower endorsed the idea of a civil rights commission to investigate what he called “allegations” of discrimination in voter registration and employment, he did so, wrote his biographer Stephen Ambrose, in the hope “that such a commission would act as a buffer to keep the race issue out of partisan politics and reduce tension.”

In the same vein, when Brownell finally persuaded him to endorse civil rights legislation in 1956, Eisenhower assured Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson of Texas that the initiative represented “the mildest civil rights bill possible.” The bill originally embraced four provisions, creating an independent civil rights commission, forming a civil rights division in the Department of Justice, establishing new safeguards for voting rights, and facilitating access to the courts for preventive relief in civil rights cases. But Eisenhower wavered in his support of the last two of these measures, stalling the legislation until nearly the end of 1957. Moreover, his support for the bill, never strenuous in any event, owed in large measure to his belief that if there must be federal pressure brought to bear in the civil rights area, it was greatly preferable to apply it to the formal issue of the franchise than to the far more troublesome matter of school integration.

The ultimate and unavoidable test of Eisenhower’s leadership in the civil rights area came with the eruption at Little Rock’s Central High School in September 1957. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus ringed the school with national guardsmen to prevent several black students from matriculating. In a typically conciliatory gesture, Eisenhower received Faubus at the presidential vacation retreat in Newport, Rhode Island, and accepted the governor’s assurances that he would direct the Guard to cease preventing the black students from entering the school. When Faubus then failed to change the Guard’s orders and rioting broke out, Eisenhower sent in one thousand paratroopers from the 101st Airborne Division to maintain order. He also cut short his vacation to return to Washington for a nationally televised address to the nation on the events in Little Rock.

Yet even in the face of this crisis, the president offered no judgment on the question of integration itself. Instead, he justified his actions as mandated by his duty to maintain order and respect for the directives of the federal courts. “My biggest problem,” he wrote to a friend, “has been to make people see…that my main interest is not in the integration or segregation question. My opinion as to the wisdom or timeliness of the Supreme Court’s decision has nothing to do with the case….” Later, reflecting on the episode in his memoirs, he carefully cited legal and historical precedent for his armed intervention but still offered no opinion on the substantive issue of integration and, beyond it, the whole knotted topic of racial justice that had provoked the incident in the first place.

Eisenhower, in short, took a narrowly proceduralist approach to the subject of civil rights. He exerted himself minimally and repeatedly for-swore opportunities to use his vast personal influence—what Dewey had called his enormous “asset” of possessing “the affection or respect of our citizenry”—on behalf of equality for African Americans. Even Stephen Ambrose, his usually sympathetic biographer, sadly concluded that “on one of the great moral issues of the day, the struggle to eliminate racial segregation from American life, he provided almost no leadership at all. His failure to speak out, to indicate personal approval of Brown v. Topeka, did incalculable harm to the civil-rights crusade and to America’s image.”

HOW TO EXPLAIN the striking contrast between Eisenhower’s sweepingly successful leadership of the Allied cause in Europe during World War II and his disappointing failure to provide leadership to the cause of civil rights as president? His personal sentiments about race relations no doubt restrained him in part, but they seem insufficiently formed and too weakly held to constitute a full explanation. James David Barber accounts for what he sees as war hero Eisenhower’s mostly lackluster presidential performance by noting the inherently different contexts in which military and political authority are exercised. “In the invasion of Europe,” Barber wrote, “Eisenhower’s brand of coordination went forward in a context of definite authority…. In an Army at war, coordination takes places behind the advancing flag: the overriding purposes are not in question. In the political ‘order’ the national purpose is continually questioned, continually redefined as part of the game.”

This important distinction compels a further question: Exactly what attributes of leadership served Eisenhower so well in the one situation and so badly in the other? As psychologists Dorwin Cartwright and Alvin Zander put it, “the skills possessed by a designated leader or the holder of an office may make him well-qualified to perform important group functions under certain conditions and poorly qualified under others…. The specific requirements of the group’s tasks demand that members possess certain skills in order to serve the appropriate functions. If the task changes, different behaviors are required, and the same person may or may not be able to perform in the new way.”

Here it is important to introduce a further distinction between those leadership skills that are conducive to the definition and achievement of a specific goal, on the one hand, and those that contribute to the maintenance of a group’s sense of its own integrity, shared identity, and common purpose, on the other. This distinction has been described as differentiating task-oriented and process-oriented leadership attributes. The identification of these discrete components of leadership has been empirically documented in laboratory studies of group behavior by psychologists Robert F. Bales and Philip E. Slater.

Bales and Slater gave each of several experimental groups, all composed of male Harvard undergraduates, an “administrative problem” whose resolution required a “group decision.” After each group meeting, individual members were asked to name the member who had contributed the best ideas, the member who had done the most to guide the discussion and keep it moving, and the member they had liked best. At the conclusion of the fourth and final meeting, individuals were asked: “[W]hich member of the group would you say stood out most definitely as a leader in the discussion?”

A striking result of this experiment was the consistency with which the subjects differentiated the roles of task specialist and socioemotional specialist (or process specialist). The task specialist typically took the initiative in conversation, defined the nature of the objective, and kept the discussion focused on the requirements of the task. His success might be measured by the extent to which he devised a viable plan of action and elicited sufficient agreement (not necessarily unanimity) within the group to realize that plan. The socioemotional specialist typically listened and responded more to others, endorsed their suggestions, encouraged their participation, and sometimes relieved tension with jokes. He was usually better liked than the task specialist. His success might be gauged as a function of the group’s ability to maintain a sense of corporate identity and purpose. Virtually all groups expressed these distinct functions, and significantly, they were nearly always performed by different individuals.

Bales and Slater also gave all their subjects a test of personality characteristics known as the California F-scale, which measures attitudes of rigidity and absolutism associated with the characterological structure that T. W. Adorno described as “the authoritarian personality.” Among the items about which the test inquired was the degree to which each subject liked or disliked his peers. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the men identified as “best liked” in the various groups were those who made the fewest distinctions about whom they themselves liked. They said, in effect, “I like everyone.” But that lack of differentiation correlated significantly with a high F-score, indicating “a certain rigidity in the attitudes of many best liked men toward interpersonal relationships. They may ‘have to be liked’ and may achieve prominence in this respect because of the ingratiating skills they have acquired during their lives in bringing this desired situation about. Their avoidance of differentiation in ratings may be an expression of the compulsive and indiscriminate nature of this striving.”

By contrast, the person who emerged in the various groups as the task specialist was rarely the best liked and, in turn, made more distinctions of his own about those whom he liked. This evinced his ability “to be able to face a certain amount of negative feeling toward him without abandoning his role.” Some negative feeling toward the task specialist, Bales and Slater concluded, was inherent in the very nature of his role:

The task specialist tends to arouse a certain amount of hostility because…his suggestions constitute proposed new elements to be added to the common culture, to which all members will be committed if they agree. Whatever readjustments the members have to make in order to feel themselves committed will tend to produce minor frustrations, anxieties, and hostilities…. Unfortunately, the very person who symbolizes the demands of the task, and presses for the extension of the common culture in a previously uncharted direction, is in a sense a deviant—a representative of something that is to some degree foreign and disturbing to the existing culture and set of attachments.

THESE TYPOLOGIES CAN contribute to an understanding of the particular leadership qualities of Dwight Eisenhower. He was at his best when the goal was defined for him, at least in broad outline, as in his assignment to win the war in Europe. In that context he could assume at least a rough measure of agreement among his followers on the objective to be achieved. His job was to orchestrate the energies of his subordinates, sustain their sense of shared and realizable purpose, and extract from each of them maximum contributions to the common effort. As Bales and Slater’s results suggest, those functions are necessary to the effective operation of any group, and Eisenhower’s brilliant provision of them as supreme Allied commander evidenced a commendable capacity for leadership on that crucial dimension.

But on the dimension that required the definition of a goal and the ability to face sometimes ferocious hostility among followers in the effort to accomplish it, Eisenhower proved woefully deficient. His deficiencies derived from deeper causes than differences between the military and political realms. They stemmed from the limitations of his own character.

Some of those limitations were evident even during Eisenhower’s ultimately triumphal performance as supreme commander in Europe. Many of his wartime associates criticized his indecisiveness when caught, as the military historian B. H. Liddell Hart put it, “in the uncomfortable position of being the rope in a tug of war between his chief executives.” The most notable example of this paralysis of leadership occurred during the drive to the German frontier following the breakout from the Normandy beachheads in late 1944. At this moment in a rapidly unfolding battle of pursuit, Eisenhower, as the commander in the field, probably had more strategic discretion than at any other moment in the war, and his immediate subordinates noisily tried to push him in different directions.

British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery pleaded with Eisenhower for sufficient fuel and munitions to strike swiftly parallel to the Channel and North Sea coasts to Berlin. The American generals, Omar Bradley and George Patton, urged that those same resources be put at their disposal to support a massive, broad frontal push into the German industrial heartland of the Ruhr. Eisenhower ultimately settled on the broad frontal strategy, but only after weeks of hesitancy and futile efforts at compromise. Patton angrily claimed that Eisenhower had put harmony before strategy, and he called the resultant delay “the most momentous error of the war.” Bradley later commented that though Eisenhower “was a political general of rare and valuable gifts…he did not know how to manage a battlefield.” Montgomery echoed this sentiment when he said that Eisenhower “knew nothing about how to fight a battle.” Alan Brooke, chairman of the British chiefs of staff, concurred: Eisenhower was “a past-master in the handling of allies, entirely impartial and consequently trusted by all. A charming personality and great co-ordinator. But no real commander.”

Eisenhower, in short, was by both inclination and experience a superb process specialist, expert at orchestrating the efforts of his colleagues. He was considerably less gifted as a task specialist, whose function was to give decisive definition to a goal and to absorb the hostility that resulted from necessarily divisive choices. He naturally fastened on the requirements of group harmony as his premier objective and indeed frequently defined the essence of leadership in terms that excluded all else.

During the war he had advised Mountbatten, first and foremost, to cultivate “mutual respect and confidence among the group of seniors making up the allied command.” Nearly twenty years later Eisenhower elaborated on his conception of the leader’s role in a letter to New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Touching on the relation of moral principles to leadership, he wrote: “In almost every field of thought and action, humans seem to distribute themselves almost according to a natural law, from one extreme to the other…. [W]hat might be called the compatible group is about two-thirds of the aggregate.” The dictates of moral principle might cast issues in black and white, he continued, but “the task of the political leader is to devise plans along which humans can make constructive progress. This means that the plan or program itself tends to fall in the ‘gray’ category. This is not because there is any challenge to the principle or to the moral truth, but because human nature is itself far from perfect.”

That frank rumination vividly illustrated Eisenhower’s temperamental commitment to moderation. It also conspicuously demonstrated his belief that the power to lead was exclusively confined to people already compatible. Here in its amplest form was the mentality of the process specialist, devoted above all to group maintenance.

Like Bales and Slater’s process specialists, Eisenhower showed a deep need to be liked. Whether in the privacy of his diary or the pages of his published memoirs, his descriptions of other individuals typically open or close with a statement of his warm regard for the person in question. “A leader’s job,” he told a friend in 1954, “is to get others to go along with him in the promotion of something. To do this he needs their goodwill.” But as Thomas Dewey had warned him, taking positive stands on issues—especially an issue as volatile as race relations—would rapidly deplete that stock of goodwill. Here perhaps, at a deep level of personality and character, lay the explanation for Eisenhower’s failure to expend the enormous goodwill he enjoyed on behalf of civil rights. Simply possessing goodwill was far more important to him than actually using it for political purposes. The public affection that Dewey correctly labeled Eisenhower’s greatest asset was, in the last analysis, not a means for the achievement of particular goals, but for Eisenhower an end in itself. He is unimaginable in the posture of Franklin Roosevelt in 1936, acknowledging that his opponents were “unanimous in their hatred for me, and I welcome their hatred!” Indeed Eisenhower’s principal criticism of the Democrats under Roosevelt and Truman was that they had fostered class conflict in American society.

This was not a temperament well suited to dealing with the unavoidably conflictual issue of civil rights. When it came to race relations, there was no naturally “compatible group” that needed simply to be orchestrated in pursuit of a consensual goal. There was instead the historic hostility of two races, reconcilable only by the exercise of “transforming leadership,” able to embrace conflict and exploit it creatively. That sort of leadership Dwight Eisenhower was characterologically incapable of providing.

“[T]here are different ways to try to be a leader,” Eisenhower acknowledged at the beginning of his presidency, when many people were urging him to assume an assertive role. “I simply must be permitted to follow my own methods, because to adopt someone else’s would be so unnatural as to create the conviction that I was acting falsely.” His own methods remained those that had served him so well as supreme commander: “fair, decent, and reasonable dealing with men” avoiding “the false but prevalent notion that bullying and leadership are synonymous” and “the use of methods calculated to attract cooperation.” At the end of his presidency he summed up: “In war and peace, I’ve had no respect for the desk-pounder, and have despised the loud and slick talker. If my own ideas and practices in this matter have sprung from weakness, I do not know. But they were and are deliberate or, rather, natural to me. They are not accidental.”

Eisenhower’s ideas and practices with respect to leadership were remarkably consistent over his career. They suited him admirably in war, when he need not define the goal to be accomplished and could take as essentially given a disposition to cooperate on the part of the people he was called upon to lead. But when it fell to him as president to define the very agenda of American life, especially in the contentious arena of civil rights, he could not do it. Specifying a task of such magnitude and facing the hostility that its designation and pursuit entailed were simply beyond him.

Paradoxically, the man who had distinguished himself in history’s greatest military conflict harbored a deep characterological aversion to conflict among his military colleagues as well as in the civil society over which he eventually presided. Ironically, the very skills of process leadership that gained Eisenhower such immense popularity and thus uniquely positioned him to transform his countrymen’s values on the race question evidenced a personality incapable of embracing the necessarily divisive role that civil rights leadership required.

These were Eisenhower’s personal strengths and weaknesses as a leader, but they perhaps also reflected values deeply rooted in the very culture that had nurtured him. “Eisenhower’s beliefs, and his expression of them,” concluded Ambrose, “were those of Main Street.” The famed British philosopher and historian Isaiah Berlin said of Eisenhower at the end of the war that the American public had the “conviction that he symbolizes something essentially American.” That essential something perhaps included the need for social comity and tranquillity, even at the expense of social justice. That need may have been especially acute in the 1950s, after two decades of depression and war. In that limited sense and without blinking at the price of justice delayed for African Americans, Eisenhower as warrior and as president may indeed have been an American for all seasons.