Chapter 2

Automata

Between 19th November 1977 and All Fool’s Day 1985, Automata produced around sixty-five computer games, and I insisted on three rules for all of them. The first rule was that they were non-violent. The second rule was that they parodied ordinary games to make players laugh. And the third rule was that they included audio tracks as a bonus to the gameplay.

The Automata logo was designed with a nod to the 1899 painting by Francis Barraud of his brother’s dog Nipper listening to an Edison phonograph, His Masters Voice. To put it in keeping with our slogan, “there’s no blood in our games, it’s Automata sauce”, I used a tomato instead of a phonograph, and the cute little dog became rusty clockwork, but even so I received a letter from HMV’s lawyers threatening to sue. After careful consideration and a consultation down the pub with a bloke called Rodney, who had once failed a solicitor’s clerk exam and so knew a thing or two about the law, I responded with a nicely typed letter saying “Fuck Off”, and never heard from HMV again. In the future there would be more law suits from global sharks trying to intimidate us feeble minnows, as will be revealed.

When Automata started, our games used one kilobyte of memory each, because home computers didn’t have any more juice. Today, my standard mobile phone packs a punch 32 million times more powerful, and the data arrives invisibly through the air. Back then our data was loaded into a primitive home computer from an audio cassette recorder, and we duplicated our stuff by hand on a four-way deck at eight times normal speed. It may seem antediluvian today but it was state of the ark then, and we were able to turn out forty or fifty copies of commercial computer games an hour, complete with self-adhesive labels and fancy cassette sleeves.

The thing about audio cassettes was they had two sides, and the thing about computer data was it only needed to be recorded on one side of the tape. So what to do with the blank side? I reckoned the obvious thing to do was record little audio scene-setters and comedy sketches to enhance the gameplay, but after the first couple of years I gave each Automata game its own theme song, and stuffed the songs with references and clues to the games. This would be called transmedia sometime in the future, back then it was called economising.

We couldn’t afford studios or musicians, but that wasn’t the real reason I ended up performing everything myself on those cassette backsides. The real reason was because I enjoyed it, in fact I enjoyed it a lot more than writing lines of computer code. I was a weak musician and a crap singer, but I multi-tracked everything and edited out the bum notes before force-feeding my stuff to anyone who’d listen.

It was good to discover that the players of Automata titles not only wanted more games and more music from us, but they also wanted to make direct contact with the Automata team. For some of them, we became an important part of their lives. But it was a surprise for me to discover who these players actually were.

The maxim “know your audience” is a basic prerequisite in the entertainment business. Without this knowledge an entertainer is wasting everybody’s time. Back in our radio days of the 70s, I knew exactly who my audience was. They were adult, nocturnal, erudite and living in the South of England. And I treated them accordingly. But if we were to meet in the street, then we would have had absolutely no notion that our common link was that of games-maker and games-player. But when the British computer boom arrived, so did micro-clubs, micro-fairs and micro-fests, and we got to meet the Automata games players in the flesh. They were smaller than I had expected.

Unlike my remote radio audience, I found that I was no longer writing games for adults, but for players that included a great many children from different locations, backgrounds and cultures. I was not at all inclined to change the stuff I wanted to produce, so there was only one course of action open to me, and that was to treat the little sods as equals. If they didn’t quite understand some of the adult themes, and if they didn’t quite pick up on the historical references or wordplays, then I reckoned it was better for them to float to the top of my pond, because I was certainly not going to meet them at the bottom. It was good to make them laugh, but it was equally good to make them think.

Some of those children would come back into my life thirty years later, and change it for the better. But in 1981 I had no reason to know who they would grow up to be or what they would grow to achieve, and neither could I suspect how catalytic they would become.

It did not take very long for the nascent video games industry to start spoon-feeding children variations on the theme of killing anything that moved, and my unease with simulated violence grew. If I wasn’t prepared to make professional compromises concerning my players then neither was I prepared to ditch my civilian hobby of non-violent direct action against assholes. And if this involved force-feeding agit-prop propaganda to kids then I had absolutely no problem with that. It would not take long for other games-makers to lower the age of mental cannon-fodder from eighteen to eight, so if I was waging a one-man war against computerised violence then I reckoned the rest of the industry could take it.

To tell the truth, the rest of the British video games industry didn’t amount to very much at the time. It may have grown out of its cradle, but it was still crawling around the nursery.

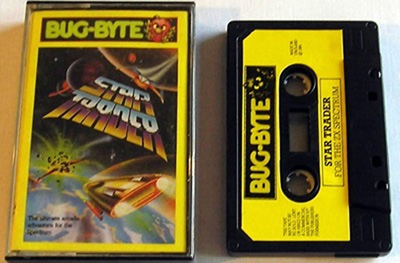

In the summer of 1978, a Liverpudlian accountant called Bruce Everiss had opened the Microdigital shop in Brunswick Street, and began to sell exotic computers from America with weird names like Apple II and TRS-80, alongside sweet little self-assembly jobbies developed this side of the Atlantic.

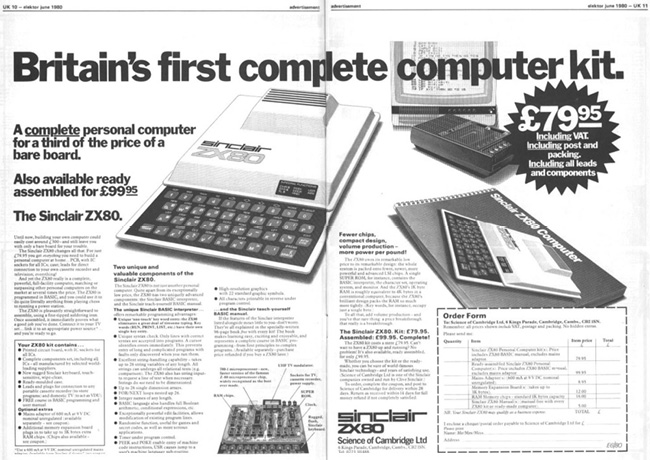

But it was the arrival of the British designed ZX80 home computer that was the real game-changer. A couple of years later, some of Bruce’s employees and customers got together to set up the Bug-Byte outfit, which specialised in computer gaming, and at last Automata had some company as well as some competitors as a few others set up to join in the fun, and try to make a living out of this new form of entertainment.

Bruce himself became operations manager of the highly-successful Liverpool outfit Imagine. Although I suspect the name was not so much a tribute to John Lennon as a tribute to the way Bruce treated his accountancy. Ten years later he would be reduced to asking me to write and perform topical computer jokes via a premium-rate phone line, and I would be reduced to accepting. He would pay me thirty-five quid a throw, and sometimes he would not pay me at all.

Much has been written about Clive Sinclair and his Z80, ZX81 and Sinclair Spectrum micro computers, and I have no intention to add more here, seeing as I only met him twice. The first time I told him that his machines were toys for playing games on, and he responded by looking at me in the same way Miss Crunt had done years before, only without the drool and the lipstick. The second time was at a party, when I didn’t talk to him much because he seemed to be talking to himself and putting on a melancholy performance of shy-man-dancing. Best not to intrude. Whatever the case, without Clive Sinclair the success of the British computer games boom would never have happened.

By 1981 there were a handful of computer games producers in the land, and we could all fit into one scout hut and share a taxi home. That’s not a metaphor, that’s a statement. At the start of the following year there were still less than a hundred of us, but by the end of 1982 we numbered around 460 with 1,200 titles competing for a slice of the market, and the media had begun to take notice.

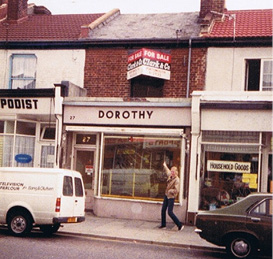

Dorothy’s Wool Shop becomes Automata

The Sinclair ZX80 launch advert

Some things caused by Bruce Everiss.

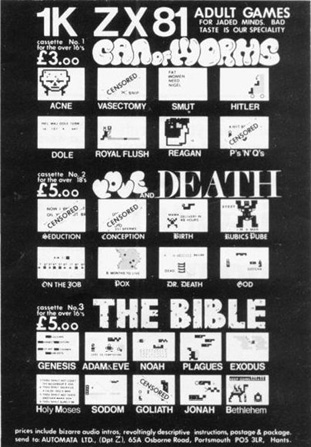

As for Automata, we were still happily producing holiday guides in print and on cassette, as well as a few radio magazines, when our first proper commercial success in video gaming happened by accident in 1981. It was the result of a bulk buy of low-quality C30 audio cassettes used for recording our audio guides to tawdry tourist destinations. C30 meant that the recording time available on each cassette was fifteen minutes a side, so I reckoned I could get rid of our stockpile by filling them up with as many games and audio entertainments as possible and flogging them cheap. The result was a compilation tape called Can Of Worms, packing in eight games and eight comedy tracks for the grand sum of £3. We had no overheads or business sense, and we sold them mail-order-only direct to the players, so our competitors simply could not compete at that volume and that price.

When the first games software charts began to appear in the early computer magazines, we found ourselves among the best-sellers, which was nice, and soon we were headed for the top of the heap, which was very nice indeed.

There are seeds of Deus Ex Machina in that very first success, particularly in the pathetic game called Acne, which encouraged the squeezing of facial zits as they erupted. I used exactly the same concept more than thirty years later for Deus Ex Machina 2, as will be revealed later in this book. Other titles in the Can Of Worms compilation involved The Prince of Wales blocking the palace sewers with his own excrement, dyeing Ronald Reagan’s hair to prevent him starting a nuclear war, and popping a whoopee-cushion under Adolf Hitler to give him a heart attack. And so it was that the first big Automata hit was a rag-bag of peurile, simple stuff, offering instant gratification to the non-discerning player with a few minutes to spare and three quid in their pocket.

Soon it was like receiving a Sooty-the-puppet xylophone for my birthday every day, and we found ourselves competing to arrive at work first, for the pleasure of unlocking the oversized silver letterbox. Our daily presents from the games players included money and little thank-you letters, so as a reward to our fans we increased the price of the next compilation tape from three quid to a fiver.

I called the second album of games Love And Death, and it featured several forerunners to Deus Ex Machina, including the sperm race of conception and the birth sequence, as well as a rather gentle but inevitable death for the player. For the third compilation, I distilled The Bible to eight games of 1K memory each and heard the first industry rumblings to the effect that I was economically if not mentally insane.

By now, almost all of the programming was being done by Christian Penfold, a used-car salesman who had started off selling advertising on our multi-media productions. I soon discovered that Christian was dyslexic, and like many of his ilk he had an unknown and untapped natural talent for programming. It used to drive me nuts when he misread and misused Sinclair BASIC terminology, but it didn’t matter at all because he always came up with the goods using a process of osmosis. And best of all, he loved turning my daft ideas into programs a lot more than I did. Sometimes he would work through the night until he could save a finished game, for fear of losing the work in progress. Quite a lot of unfinished software went missing back then, usually when my dog wagged a cable loose, or when Christian introduced the cassette recorder to the steaming contents of the electric kettle.

When I labelled Automata titles as “adult”, “censored”, “over-16s” and “over-18s”, I was taking the piss, knowing full well that the greatest attraction for a youngster is to indulge in something perceived as out of bounds. And when I was challenged, my arguments in favour of Automata games and against war games were well-rehearsed. I trotted them out at every opportunity, from Woman’s Hour on the BBC to interviews in The Sunday Times when it was a respected newspaper before Rupert Murdoch got his claws in it. And what I said could be boiled down to this: “Would you rather your children played games that encourage them to kill or to kiss?”

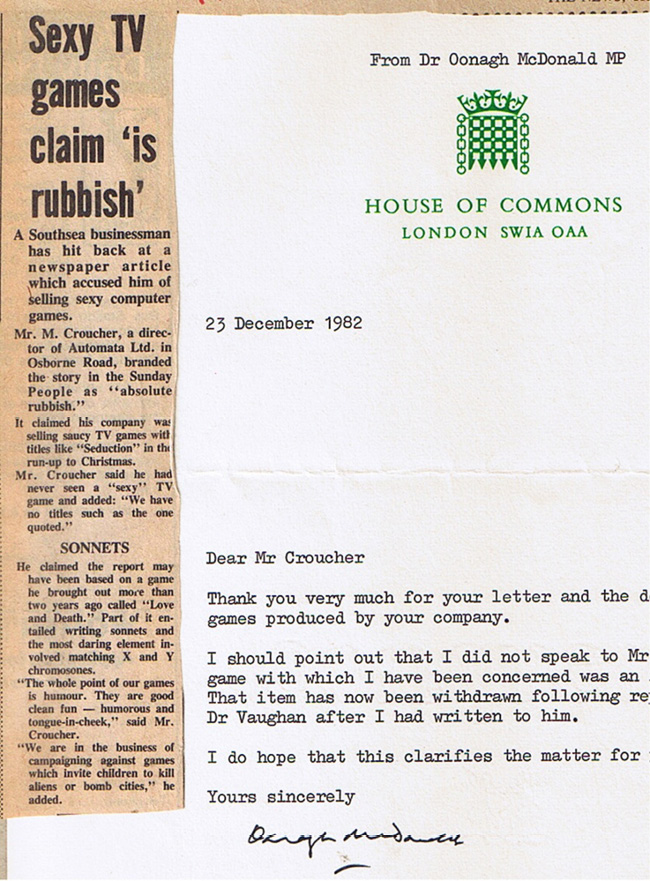

One Monday morning in December, after the first coffee had been poured and the first Frank Zappa album of the day had hit the office turntable, the phone rang and I took a call from Laurie Manifold, three years away from retirement as the investigations editor of The Sunday People, a gutter-press newspaper with a huge circulation. The resultant firestorm taught me the most valuable lesson I have ever learned in marketing a business. Never be the subject of a news interview, always write it yourself. And apart from that, the publicity was brilliant.

In the “Storm Over Sexy Home TV Games” feature which resulted, I was portrayed in the national press as a purveyor of pornography to children. An electronic child-molester. I had been in the papers before, but never branded as a criminal. Well, only once before, when I appeared in the listings of court convictions for letting my dog shit on the beach.

The accusation that Automata was a depraved cess-pit of adolescent corruption became a contentious subject, and was taken up by Dr. Oonagh McDonald, a Labour Member of Parliament. Questions were raised in The House Of Commons concerning the dangers of this new video games phenomenon that was sweeping the country, and I was determined to state my case to her.

It was soon apparent to both of us that we were on the same side, and fuelled by a mutual loathing of the gutter press and a desire to spike the guns of violent video games, we formed an unlikely alliance, mostly over the phone, which was a challenge for Oonagh because she was deaf.

But a lot of other people were tuning in loud and clear, and Automata was now a household name in the growing number of households that knew what video games were. Then, on April 23rd 1982, the Sinclair Spectrum was launched, and Automata was poised, ready, willing and able to take a crack at making a little bit of gaming history.

Christian Penfold with Rory the Irish Setter

Automata advertising / The wick’ed Mel Croucher

A nation corrupted by 1K of monochrome evil