Chapter 8

The Wilderness Years

When I abandoned Deus Ex Machina first time round, I thought all I had to do was wait a year or two until technology caught up and delivered a platform that could play the full version of what had been in my head. As usual, I was wrong. I had to wait a quarter of a century, first for the internet to be invented, and then for mobile games machines to go portable.

Everybody knows that the Internet was invented in March 1989 by the Great British computing visionary Sir Tim Berners-Lee. Right? Wrong! Come with me to Mons, a medieval Belgium collection of rather narrow houses and rather wide occupants. In a little side-street in a crumbly part of town, is a miniature museum called the Mundaneum, dedicated to a forgotten visionary named Paul Marie Ghislain Otlet. To me Otlet was a dead ringer for the British mass-murderer Doctor Harold Shipman, but his legacy to the world was much more remarkable.

In 1892, at the tender age of 24, Otlet published the provocative notion that storing information on library shelves was a really dumb idea, because individual facts are difficult to locate and their arrangement is at the mercy of a bunch of opinionated pen-pushers. Otlet reckoned it would be far more useful and a whole lot faster to store information as “data chunks”, to allow “continuous manipulation and interfiling” by “linking one concept to another.” By the end of 1895, he had built his first searchable storage facility, with 400,000 entries held on individual data cards. Amazingly, in his own lifetime it would grow to over 15 million listings. Can you see what it is yet?

In the twentieth century, Paul Otlet embraced multimedia, by integrating microfilm and audio into his system, now called the Mundaneum. He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1913, for proposing a global sharing of his information network, to prevent international misunderstanding and conflict. But that did a fat lot of good, seeing as how the First World War promptly erupted. Undaunted, he went on to propose the electronic transmission of his system via radio and television, and because there was no such thing as electronic data storage, he set about inventing it. In 1934 he designed the internet as a gigantic “réseau” which translates exactly as “network”, which would employ a massive number of workers operating computers, or “electric telescopes linked as a mechanical, collective brain”, as he described them in his charming Belgian way. He laid out how ordinary people would use the web to browse millions of interlinked chunks of knowledge, opinions, images, audio and video files. But best of all, he described how his network could be used for a paperless future to share files, send messages and form social networks. “Anyone sitting in an armchair will be able to contemplate the whole of creation.” And if that isn’t an accurate blueprint for the entire damned world wide web, then I don’t know what is.

Paul Otlet snuffed it in 1944 when the Nazis walked in to the building that housed his Mundaneum, and ripped the guts out of it. Today, he is a forgotten man, even in Belgium. Even in Mons. For shame! Stand aside Sir Tim, and let us honour Paul Otlet, the true founder of the Internet. Anyway, to get back to the story, as I waited year after year for the Internet to come along and get popular, I had to find something else to do.

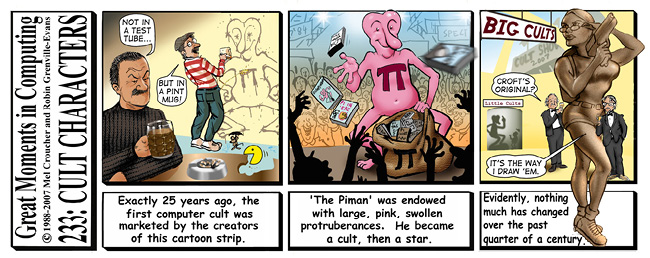

My daily bread came from writing: journalism, comedy, computer manuals, sci-fi, music revues, and loads of cartoon strips in partnership with my old mucker Robin Evans. My butter came from new technology, which meant pushing the boundaries of electronic marketing as far as I could, and doing what we had always done at Automata, which was getting direct to the end-user by cutting out any distributor, wholesaler, retailer, agent or other parasitic life-form.

As computers began to invade the workplace, and in particular the office, I shamelessly ponced and tarted my ideas to any multinational who would listen. I was ready to sell my principles to any corporate or brand who I could talk into injecting their marketing with a slice of electronic anarchy in exchange for some serious money. I had done with earning a pittance.

I will summarise 1985 to 2010, as The Wilderness Years. But unlike the Christ, who only went walkabout for forty days and forty nights, I wandered from my own Deus Ex Machina for twenty-five years. I began those Wilderness Years waiting for technology to catch up with the sort of video games and entertainments I wanted to create, but after a while I forgot all about such things. And now that epoch has ended, the mirror tells me I am old, and to prove it the State gave me a senior citizen’s bus-pass years ago. As Ian Dury liked to say, “all I want for my birthday is another birthday.”

During that quarter of a century I did things that were not great game-changers but neither were they a complete waste of time. What they all had in common was the dreadful compulsion to do-it-first. It’s weird how compulsive Do-It-Firsters never learn what a fundamental error it is to pioneer anything. Looking back, it’s clear that those who really benefit from innovation are those who wait for the pioneers to make all the mistakes by proxy, learn from those mistakes, extract the essence of success, ditch the crap, and cash in. As for me, I am content being a footnote in the story of video gaming, and even more content with what came out of The Wilderness Years. Let’s deal with those years as quickly as possible so we can get back to the real story.

I spent a few years dallying in artificial intelligence and trying to inject my software with emotional intelligence to humanise the machines. My ambition was to build a genuine relationship between avatar and human. I failed of course, but not too badly, and then got serially sidetracked in hitting print deadlines. Then in 1993 I produced a video game called Run The Bunny for Duracell, the battery manufacturers. It used trackable routines embedded in product placement software. Run The Bunny exploited Paul Otlet’s internet concept, and another new-fangled strategy called ‘let’s stick a floppy disc on the cover of this magazine in a desperate attempt by the publishers to attract more buyers.’ It also exploited an old-fangled concept called bootlegging, where I actively encouraged players to copy the game. These days the industry calls this strategy viral marketing, twenty years ago they called it bonkers. I called it fun, and quite lucrative.

The real-world element of the Duracell campaign involved field-testing smart batteries. The gaming element involved my idea from the very first computer games I had produced back in the 70s, which was to offer prizes in exchange for information. It consisted of shoving virtual batteries up the virtual arses of virtual Duracell pink bunnies. The incentive was that if you copied the game and someone you seeded it to won a prize like a laptop, a cell phone, or other battery-powered stuff, then you would also win exactly the same prize, provided we knew who you were, your email address, what hardware you owned, what hardware you would like to own, what underwear you favoured, and whose oxen you coveted. I coined the word “adware” for that one, which has since come to mean something quite different. We produced Run The Bunny in eleven languages including Mandarin and Russian, I mounted it on half a million computer magazine covers for “free”, and I think it was the first viral marketing campaign to go global. It ran on PC only and it sucked in 100,000 sales leads for my client. They seemed quite pleased.

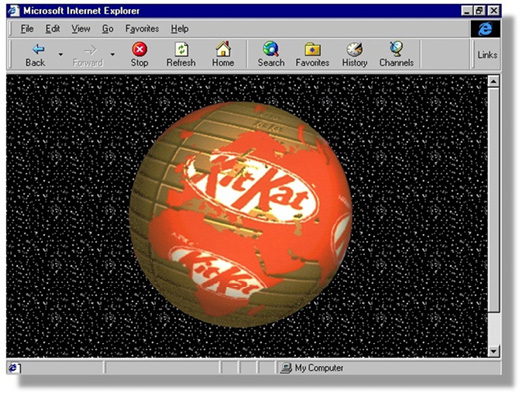

My next viral marketing campaign was called Take A Break for the four-fingered chocolate-mongers at KitKat, and I am under a legal embargo agreed with Nestlé not to mention specific details. Particularly the lawsuit I threatened them with and the fact that my legal representative was barely out of school. Essentially, groups of office workers would waste their employer’s time staring at a KitKat screensaver of a chocolate planet Earth. As the planet revolved on their computer monitor, cities appeared as illuminated beacons, and the idea was for these office workers to identify all the cities, eat a whole load of KitKat and answer a daft tie-breaker, in order to win a world trip to all of the cities illuminated on the chocolate globe. Again, it was based on the “please copy me and pass me on” viral principle. I am ashamed to admit that one of those cities only appeared for an eye-blink every half hour. It was Dubai. Sorry for wasting all that office time.

My favourite viral marketing campaign for a bunch of multinational capitalist bastards involved free beer, which was how I squared it with my conscience. One of my clients in the 1990s was Bass Breweries, and one of my duties was to run a website for them called It’s A Scream, which was meant to encourage students to abandon their studies in favour of the pub. Obviously, each branch of the Scream chain was strategically located within puking distance of a university campus.

One winter morning in my office, long before the first Frank Zappa CD hit the speakers, the analogue vinyl having been replaced a decade earlier, and the old dead dog having been replaced by a new live one, a sharp-sighted member of my little team spotted an anomaly in the overnight web stats. There had been a spike of activity based around the Norwegian capital Oslo, including successful downloads of the entire site and unsuccessful attempts to hack the servers. We ran a reverse ISP thingy check, and instead of revealing a bunch of Scandinavian students trying to copy the source code of our online games, up popped a bunch of Norse lawyers. Üh-øh.

It took one hard look at the It’s A Scream logo on our website to work out what was going on. The logo was a rip-off of the screaming skull of Edvard Munch’s iconic painting The Scream. Munch was Norwegian, and a couple of quick checks informed us the image was very much in copyright and the lawyers represented the artist’s daughter. I phoned Bass Breweries to tell them I had just pulled their website and replaced it with the image of a pint of beer, and hoped to save them a small fortune in punitive damages. As it turned out, the Edvard Munch estate refrained from suing them, but it cost them a small fortune anyway to change all the signage on all the Scream pubs that infested the land. However, the marketing boys at Bass suddenly started treating me with a bit of respect, especially when they listened to my predictions that this internet thing was going to become a central part of student life, not for playing games, but as a social network. They gave me a budget, and they gave me the go-ahead to let rip on a viral marketing campaign.

And so I built a database based on the Duracell and KitKat campaigns that was to become the model for all my future attempts to deal direct with an audience. One that got end-users to reveal who they are, where they are, and what they want, then encourage them to get their mates involved, and then track the results, and then flog them stuff.

Populating the database was surprisingly easy. Instead of entertaining the student community with yet more video games, we linked up to as many of their websites, discussion boards and online networks as we could find, and offered them free beer. All they had to do was tell us when their next piss-up was going to be and which branch of a Scream they were going to inflict themselves on, and there would be a free pint waiting for them behind the bar. Well, that was not quite all they had to do. We also needed their email address and those of half a dozen mates, so we could plague them with future offers. And their mates had to attend the piss-up so Bass could sell them enough beer to recoup the bribe of the freebie. We launched the campaign at the beginning of the academic year at 6 pm on Saturday 5th October 1996, and hit the nearest student networks to us on the South coast of England. By Sunday night we were getting sign-ups from as far away as Christchurch. That’s Christchurch, New Zealand.

I also spent a lot of The Wilderness Years writing puerile comedy material and grown-up cartoon strips, I sold part of my soul to magazine editors, I knocked off a short series of books about computers and marketing, and I became editor of the European Computer Trade Association yearbook. It was all very repetitive, but there was a low-level of enjoyment to be had in amongst the deadlines, and I was able to observe the bizarre evolution of video games from a safe distance. Sometimes my old chums who were now big players in the computer gaming world would invite me to act as Master of Ceremonies at the sort of awards events I had once refused to attend. And I loved it.

When you wander the creative wilderness for a quarter of a century, it’s inevitable that you stumble across other wanderers from time to time, each on their own unique pathway. Our common signposts were electronic, and channeled via the Internet, and I found myself responsible for doing all sorts of webby stuff for some very nice people as well as assorted crazies and scoundrels. Creating the first website for Vidal Sassoon was very nice indeed. My consultancy report that recommended P & O Ferries to embrace an online future was completely ignored, and they duly went bust. And there was a time when I had the entire Island of Cyprus as a client, which was just about as surreal as it sounds.

But I know you don’t really care about any of that. All you want to read about is which rock music superstars I worked with, and what dirty little secrets I can reveal about them. Well, there were a lot, and there were a lot. But this book is about the history of UK video games in general and Deus Ex Machina in particular. So I must disappoint you. The legends of modern music that I did work for were all exactly as you would expect, because you already know as much about them as I do. Bryan Adams had bad skin, Pink Floyd were middle class, La Toya Jackson’s lungs ran on helium, Led Zepplin were parsimonious, Phil Collins was bald, Van Morrison was an Irish curmudgeon and U2 were Irish minus the mudgeon. And then there was a bunch of younger generation pop stars who were all like Starbucks coffee: sweet, wet, warm and thick.

I make three exceptions to my rock music vow of silence, and that’s because the three gentlemen involved displayed a total understanding of the power of the internet, and I was able to work in their best interests to grab the opportunities offered by self-selecting online communities. Their working names were Eminem, Prince, and Frank Zappa, and they all came to me via a remarkable American mover-and-shaker called Kelli Richards. Kelli launched the digital music revolution, probably because that’s the sort of thing redheads do. She drove Apple’s early music initiatives for ten years, she kicked EMI music into shape, she launched the first internet-based music artist subscription service, and she phoned me up out of the blue to tell me we were going to work together and stiff the parasites of the music industry. I dithered. She then told me she thought she could get my hero Zappa as a client. I accepted on the spot.

My work for Eminem was by far the most businesslike. It involved him paying me money in exchange for my audit of his entire online existence, with a view to putting a net worth on it. It was worth a lot. But the fun bit was working out how much money he was hemorrhaging from illegal downloads of his music, and how much he was being ripped off by unauthorised ringtones and merchandising. He was losing a lot. He accepted my weighty report graciously, asked the right questions, quibbled over nothing and after he paid on the nail like an honourable man I never heard from him again. I hope he didn’t hire assassins to deal with the crooks I identified, but if he did, all I can say is they had it coming. At least I have a signed document to absolve me from culpability and getting my collar felt by the Feds, particularly when it came to identifying lunatics, bootleg merchants and porn-mongers.

Prince was a different kettle of fish altogether. He was possibly a genius, but impossibly remote. He knew exactly what he wanted before we even started, and that was to harness the brave new digital world for his best benefit, not to kill bootleggers and pirates but to embrace them. Auditing the internet for a generic name like “Prince” was a total bastard. It crossed over with everything from the Prince brand of cigarettes to oodles of parasitic hereditary monarchies, but we got there in the end.

There were no intermediaries, and The Artist Formerly Known As Prince dealt with every detail personally, with messages arriving electronically and very securely. We never made direct contact and I had no idea what his real agenda was until after it happened. And it happened in style. Just as for Eminem, I delivered a global analysis on what I reckoned Prince’s status was online and how best to exploit it, but unlike Eminem he moved instantly. His “official” web presence disappeared completely, and was replaced by a blank screen. A black blank screen.

And then he broke all the rules. He began to give away his music instead of selling it. He started bootlegging his own performances to include a “free live CD” in the ticket-price of that specific concert. And in order to do this he wanted one simple thing from his fan-base. Their email address. He started building a definitive global database of his fans, and he went on to break the stranglehold of the intermediaries and barriers that had gotten between artists and fans. In a sense, Prince invented the “freemium” model of giving digital media away with the intent of selling additional digital content direct to fans, time and time again. He saw it coming ten years before anyone else in his platinum league, and for this alone I genuflect before him.

I used the same team for delivering data on most of my sweet little rock and rollers, usually under the umbrella of a company I set up called My Reputation. I hired a mess of a hacker straight out of central-casting, a prickly charmer who went on to work for Her Majesty’s secret spooks, a bearded accountant who liked his real ale, and two very good looking ladies who did all the work. We operated out of an historic Clock Tower only a few steps from my home, which the lovely owner let me use at a peppercorn rent on condition I wound the clock and adjusted the ancient mechanism to display the correct time for all the Street to see. I loved that duty. It involved climbing up the near-vertical wooden stairway inside the tower, popping out of a jack-in-the-box trap door near the top, and decanting myself upwards behind and inside the four huge dials of the time machine. Then I would wind an iron handle for an eternity, as huge weights rose from street-level to the top of the tower, twice the size of the starter-crank on my old Citroën gangster car, and ten times the size of the handle on the mangle in my mum’s scullery.

During the Second World War, this Clock Tower had been used as a discrete recreational facility for high-ranking naval officers and their private guests, included Admiral of the Fleet Louis Francis Albert Victor Nicholas George Mountbatten Earl of Burma, Noel Coward and according to the very old lady who told me she used to play the piano there, a disproportionate number of athletic young men.

During my years in the Clock Tower, I dug the dirt on the reputation and assets of celebrity clients, and bred tropical fish. They seemed to enjoy the vibrations from giant speakers either side of the tank, pumping out pagan rhythms as they pumped out milt. The fish, not the celebrities.

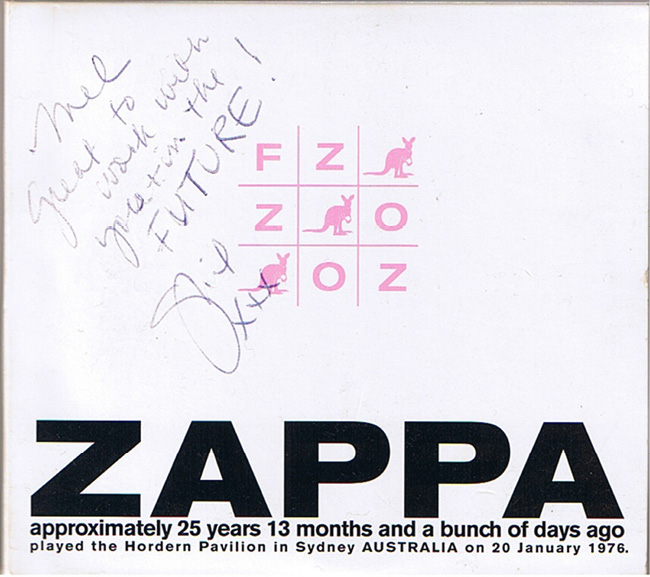

My early conversations with Gail Zappa took place on the phone after midnight. They went on for hours, and mostly involved sailing the pretend seas in a pretend pirate ship. When I met the next-generation Zappas, I was surprised how well adjusted they were, apart from Diva, the youngest, asking me if we had to kill all the bootleggers for real or was it just a game. But I didn’t do what I did for any of them. I did what I did for my all-time hero and the greatest American musical genius of the twentieth century, Frank Zappa.

Zappa was so far ahead of the curve that it would take another book to extol his manipulation of modern music to the advantage of people with the right ears, but for the purposes of this book he lived long enough to figure out that direct marketing to a global list of fans via the internet was going to change the future of music. At the time of his death in 1993, the Internet was in its infancy, and the idea of trawling it for email addresses was revolutionary. He left a legacy of at least forty completed albums in the vault, with a vision to release at least two a year direct to his fans. But first we had to beat the bootleggers.

My job was simple but it was also painstakingly detailed, and I was tasked with identifying every hub of unauthorised activity, whether it was tribute bands, unlicensed merchandise, pirate copies of his albums and videos, anything and everything, and schedule it on a global basis. Then I needed to identify those responsible. I also needed to do the same for legitimate fan activity, which proved a much less enjoyable task because they came flocking. We also knew there was a hard core of obsessive possessives out there, individuals who would always buy everything Zappa produced, for the sake of completing their collection.

The idea was to reach out and embrace the lot of them, and harness their guilt and greed, or loyalty and goodwill, by bombarding them with opportunities to buy unique and unreleased material. Just imagine if there were two hundred thousand diehard Zappa fans on the planet, and just imagine that thirty thousand of them were obsessive possessives. Now imagine if you could sell them a new album for fifteen dollars with no intermediaries taking a slice of the action. And finally imagine that you had a vault stuffed with unreleased material. Genius.

The start and finish of The Wilderness Years

Zappa died aged 52 from prostate cancer. My dad had died at 57, not from the tuberculosis of his youth, or the asbestos from his engine rooms, or even the two packs of snout a day he smoked; it was his stomach that got him. My mum was only 47 when she had a catastrophic stroke and her brain got wiped out. When my contemporaries started to die off, either from physical ailments or alcohol addiction, my focus shifted. Of course it did.

One morning, a few years after I hit my sixtieth birthday I’d got back home from attending yet another funeral, and my dog went out the back yard for a sniff, but dropped dead instead. I was not yet dead, but the clock was ticking, and it was time for a reappraisal. It was time to get back into the video games business. That’s what it was.