‘When we are dead, seek for our resting-place Not in the earth, but in the hearts of men.’

Jalal al-Din al-Rumi (d. AD 1273)

IN THE WILDERNESS of Abyan, somewhere between San’a and Hadramawt, lies Iram of the Columns, the great city built by the people of Ad. The Adites, a race of giants, have disappeared, obliterated in a burning hurricane because of their refusal to heed the Prophet Hud and acknowledge God. ‘Have you not seen’, the Qur’an says, ‘what your Lord did to Ad?’ Iram awaits archaeological investigation. The problem is that no one knows where it is. In the seventh century, a nomad stumbled across it while looking for some lost camels but never found the way again. For the moment, Iram remains veiled from sight, an Arabian Atlantis.

An extant Iram of the Columns may be a legend, a city-dwellers’ desert mirage; but Yemen is littered with more tangible remains of its early history. Some were already ancient when the Palace of Ghumdan was built. North of the Wilderness of Abyan and across the dunes of Ramlat al-Sab’atayn, a finger of sand thrusting south-west from the Empty Quarter, is the most famous of them all, in fact the most famous archaeological site in Arabia, the Marib Dam. The barrage wall is gone, but on either side of Wadi Adhanah, near the ancient Sabaean capital of Marib, the great masonry sluices are still in pristine condition more than 2,500 years after they were built.* Channels leading away from them once supplied the two gardens of Saba, the vast area of fields and orchards on either side of the wadi which is mentioned in the Qur’an.

Upstream from the Sabaean construction is a new dam. With a capacity seven times that of its predecessor, it was finished in 1986 at a cost of $70 million, paid for by Shaykh Zayid of Abu Dhabi. Irrigation works have yet to be completed, but silt deposited before the foundation of Rome is now once more covered with crops.

Shaykh Zayid’s reasons for parting with such a hefty sum were not purely philanthropic. The old dam is important not only as an archaeological site but also as a symbol of unity. For it represents the common source of those Arabs who trace their ancestry back beyond the time when nationalities were invented, to Qahtan, the son of the Prophet Hud, great-great-grandson of Sam and progenitor of all the southern tribes.

Until a little over a hundred years ago, the divisions of Arabia were expressed in loosely defined geographical terms – al-Sham, ‘the North’, al-Yaman, ‘the South’, Najd, ‘the Uplands’, and so on – and in terms of ancestral origin. A particular region might develop a cohesive cultural identity, as Yemen did early on, but there were no fixed borders. ‘Territory’ equalled ‘sphere of influence’; boundaries were as mobile as people.

This was not good enough for the expanding imperialist powers of the nineteenth century. While political officers on the ground knew where things stood, or didn’t stand, the bureaucrats of the British and Ottoman empires thought along more rigid lines. Gradually, borders were superimposed on the Arabian map, at first lightly, then with a heavier hand as oil came on to the scene. The need to decide who owned what began to arrest the old fluidity. As the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990 showed, the process is not yet over.

The British, who grabbed the port of Aden in 1839, and the Ottomans, who from mid-century onwards pushed into Yemen and entered San’a in 1872 (with the help of reinforcements shipped through the new Suez Canal), were eventually forced into drawing a border between themselves. They took a long time to do it. The Anglo-Ottoman Boundary Commission only started work in 1902, and its results were not ratified until 1913. The historical basis for the border was shaky, to say the least. Except for a brief period in the twelfth century, Aden had been politically part of the rest of Yemen until the al-Abdali family seceded from San’a in about 1730. The al-Abdalis, originally appointed as military governors of the Aden region by the Imam – the temporal ruler of Yemen and spiritual leader of the Zaydi sect – declared themselves Sultans of Lahj, and it was from them that the British took Aden. From 1839 onwards, the government in Bombay cultivated an Arabian mini-North West Frontier, raising other would-be potentates of this microcosmic Raj to the rank of Sultan and Amir. With the titles came treaties of protection and, more important, stipends: it was a border built on rupees.

To the north, the Turks were implementing a similar policy. When they left after the First World War, Imam Yahya announced his intention to reunify the country. Border clashes during the 1920s led the British in Aden first to demonize him, then bomb him. The Yemeni reaction came in a famous verse:

Go gently, Britain, gently,

For the power of God is mighty:

The power that long ago destroyed

Pharaoh, and Thamud, and Ad …

However, the two sides arrived at a status quo of sorts, which wobbled along until the British left in 1967. But the border remained for another two decades, shored up by ideological differences between the post-Imamic Yemen Arab Republic (YAR) and the post-Independence People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (PDRY). Only with Yemen’s reunification on 22 May 1990 did it seem that the imperial ghost had been exorcized, and this most artificial of Arabia’s borders effaced for ever.

Shaykh Zayid, then, by bankrolling the new dam, was reminding the Yemenis and his own people that Marib was the land of his forebears, that ancestral roots still run beneath the lines of political demarcation. The chain of events that led his ancestors to settle in what was, until recently, an insignificant spot in the lower Gulf, is traditionally presented as starting with a big bang, a single massive damburst that deprived the wealthy farmers of Marib of their livelihood and forced them to emigrate to all corners of Arabia and beyond. One version says that the ruler who owned the dam had been forewarned of its collapse by a soothsayer. One day the king’s son returned from the hunt with news that he had seen a rat with iron teeth gnawing at the dam’s foundations. (A subplot records that the rat had come from Syria by jumping from hump to hump along an immensely long caravan of camels.) Knowing that the soothsayer’s prophecy would be fulfilled, the king ordered his son to strike him in the face publicly; the boy, perplexed but dutiful, carried out his father’s orders. ‘How’, the king then asked his subjects, ‘can I remain among you now that I have lost my honour?’ He packed his bags and sold the dam to a consortium of buyers for a heap of gold, which he measured by sticking his sword in the ground and waiting until the pile of coins had reached the top of the blade. Cheap at the price, the buyers thought; they hadn’t made a structural survey. The rat completed its task and the dam broke, drowning, among others, one thousand beardless youths upon one thousand skewbald horses.

Recent archaeological research and a pocket calculator have produced a more credible but less entertaining account. It has been estimated that Wadi Adhanah brought some 3.2 million cubic yards of silt down from the mountains every year. This necessitated periodic dredging by vast labour gangs. If left unattended, the silt building up would endanger the structure of the barrage. Inscriptions record emergency repairs, one in about AD 450 and the next by the Ethiopian ruler Abrahah a century later; but the routine maintenance and rebuilding that were necessary to keep the dam in one piece had long been neglected, probably since the focus of power had shifted to the highlands with the emergence of the Himyari state there several centuries before. The dam’s final collapse later in the sixth century was a recent event for the early Muslims. Referring to it, the Qur’an says, ‘We have given them, instead of their two gardens, a harvest of camel thorn, tamarisk, and a few ilb trees.’ Until recently, this was still an accurate description of the flora of Marib.

Just as it is dramatically neater to present the long process of the dam’s decay as one cataclysmic event, so the diaspora it caused is usually seen as a single happening. ‘They dispersed like Saba’ is still proverbial for any sudden and irreversible break-up. But the history of emigration from Yemen began long before the sixth century, and continued long after.

The Yemenis who left their homeland, Sabaeans or others, were not going into the unknown: communications with the rest of Arabia and further north, as well as with East Africa, dated back to the beginning of the first millennium BC. Colonies of Yemenis sprang up along the East African coast, in Ethiopia and in Syria and Iraq, and long-distance raiding parties are often mentioned by the early historians.

Some accounts are impressively imaginative. The twelfth-century encyclopaedist Nashwan ibn Sa’id claims that there was an independent Yemeni state in Tibet, ‘the land whence musk is brought’, founded by men left behind when the Himyari King Shammar Yuhar’ish mounted an expedition to China. Nashwan also says that the king named Dhu al-Adh’ar, He of the Frights, was so called because he brought back as captives from the Land of the North some nisnas, ‘a race of men whose faces are upon their chests’. Here we are in a no man’s land of confusion and invention, first described in the accounts of Alexander the Great’s expeditions, and explored intrepidly by the monkish cartographers of Hereford’s Mappa Mundi and later by Sir John Mandeville. The nisnas seem, in fact, to be the same as the Blemmyes of European accounts, who are in turn identified with the Bejas of the African Red Sea coast. Fact and fiction had got mixed up in a geographer’s version of Chinese whispers.

There was an upsurge of migration in the early Islamic period, with Yemenis in the vanguard of Islam’s conquering armies. The populations of the new cities in Syria and Iraq were largely Yemeni. Some Yemenis went as far as Dongola in Sudan; others settled in Tunisia, intermarrying with the local Berber population. Yemenis also founded colonies in Spain and briefly occupied Bordeaux.

Yemeni blood flows across the Arab world. Some Arabs have forgotten their Yemeni origins; many have not. A taxi driver in Muscat who had identified my adoptive home from my speech refused payment, ‘because you live in the land of my grandfather. He was from Marib.’ The Omani was talking about an ancestor of perhaps fifty generations ago.

Turning off the San’a-Marib road, I headed northwards. On the left was the escarpment of the highlands, skirted by the old incense road; on the right a shimmering gravel plain extended beyond Marib until the sand crept up on it. A few depressions dotted with tamarisks marked dry watercourses; when the rain came they would feed into the great wadi of al-Jawf, where the remains of the Ma’inian capital Qarnaw lie and where the main interest of the people is, and always has been, fighting.

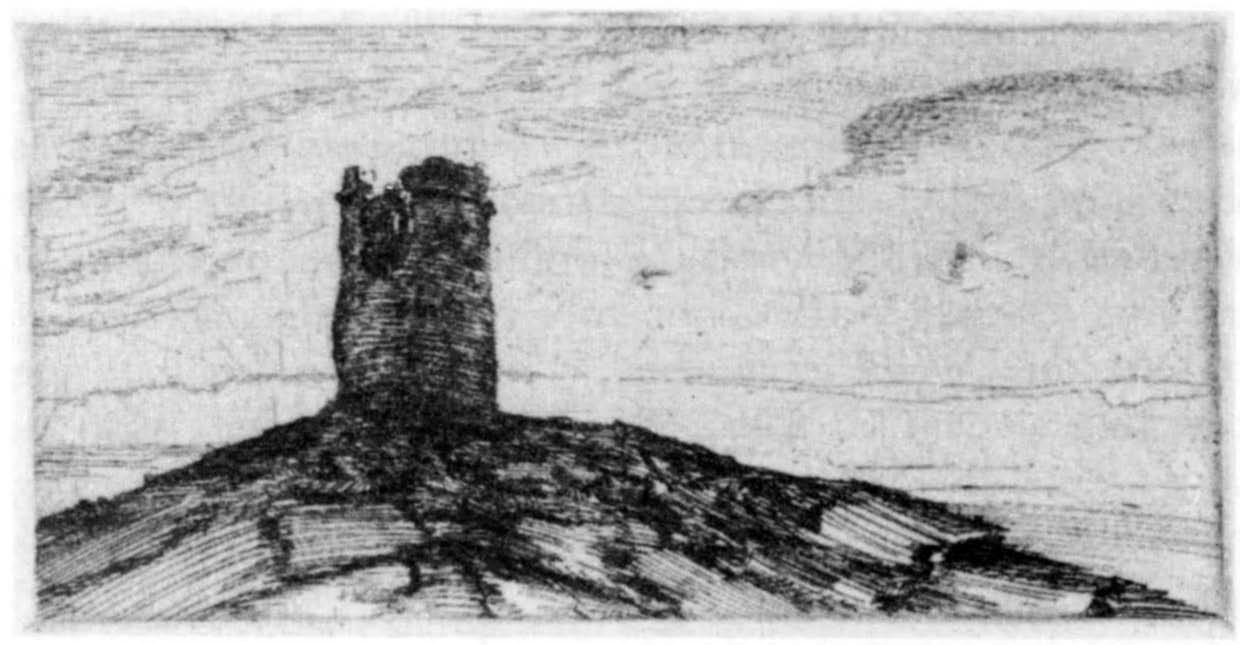

Tracks crossed and recrossed, all heading the same way. The borrowed jeep lurched and bounced, and a cloud of powdery dust streamed through its tattered canvas sides. I stopped for air and scanned the horizon: it shuddered perceptibly in the dead quiet of noon. Ahead, there was a smudge, slightly darker than its surroundings. For the next twenty minutes of driving I kept my eyes on it until it began to resolve itself into something more solid, a sight familiar from photographs but infinitely more impressive, crouched in isolation on a slight hump in the featureless plain. The sun was moving west and the sharp lines of bastions were beginning to emerge from the blank expanse of the walls of Baraqish.

I left the jeep outside the fence erected by the Department of Antiquities and walked in, the only sound dust squeaking under my feet. Suddenly a shout from the left made me jump, and a slight figure with long wild hair and an assault rifle bounded down over a hummock of silt.

He was grinning. ‘Did I frighten you?’

‘A bit.’ The blood was draining back into my face. ‘I didn’t expect to see anyone.’

‘I’m the guard,’ he said. He took my hand and led me towards the walls of the city.

At the foot of one of the bastions he stopped and squatted, unshouldering his rifle and laying it across his lap. ‘Look … look at the stones.’ He caressed the fine ashlar. ‘What machines did they have to cut them like this?’

‘They had no machines. Only hand tools,’ I replied.

The guard shook his head. I shrugged. The quality of the stonework was superb – it looked as if it had been cut from butter. (A belief used to be current among the country people that in ancient times stone would spontaneously soften in the month of August.) Inscriptions dotted the walls, recording the names of those who had paid for their construction over two millennia before, when for some three centuries the wealthy merchants of Ma’in formed a state independent of Saba. The inscriptions might have been carved yesterday. The masons of Baraqish put their successors to shame, and if evidence were needed of the high level of sophistication they had achieved, here it was: as building, it was not just defensive, but conspicuously, consciously beautiful; as craft, it was perfect. The epitaph on the Himyaris attributed to the poet-king As’ad al-Kamil applies equally to the people of Ma’in:

These are our works which prove what we have done;

Look, therefore, at our works when we are gone.

Si monumentum requiris, circumspice.

The guard seized my hand again and pulled me up a collapsed section of wall. Inside were the remains of later buildings, including a circular tower or nawbah. Potsherds and fragments of glass, mostly multicoloured bangles, littered the ground; many scraps of faded indigo cloth were embedded in the dust. Baraqish has had a series of occupants. Aelius Gallus, the Roman governor of Egypt, garrisoned it before his unsuccessful attack on Marib in 24 BC; twelve hundred years later Imam Abdullah ibn Hamzah, whose descendants still live in the villages nearby, used it as a base against the Ayyubid invaders. Both of them must have been overawed by the architectural achievement of their predecessors.

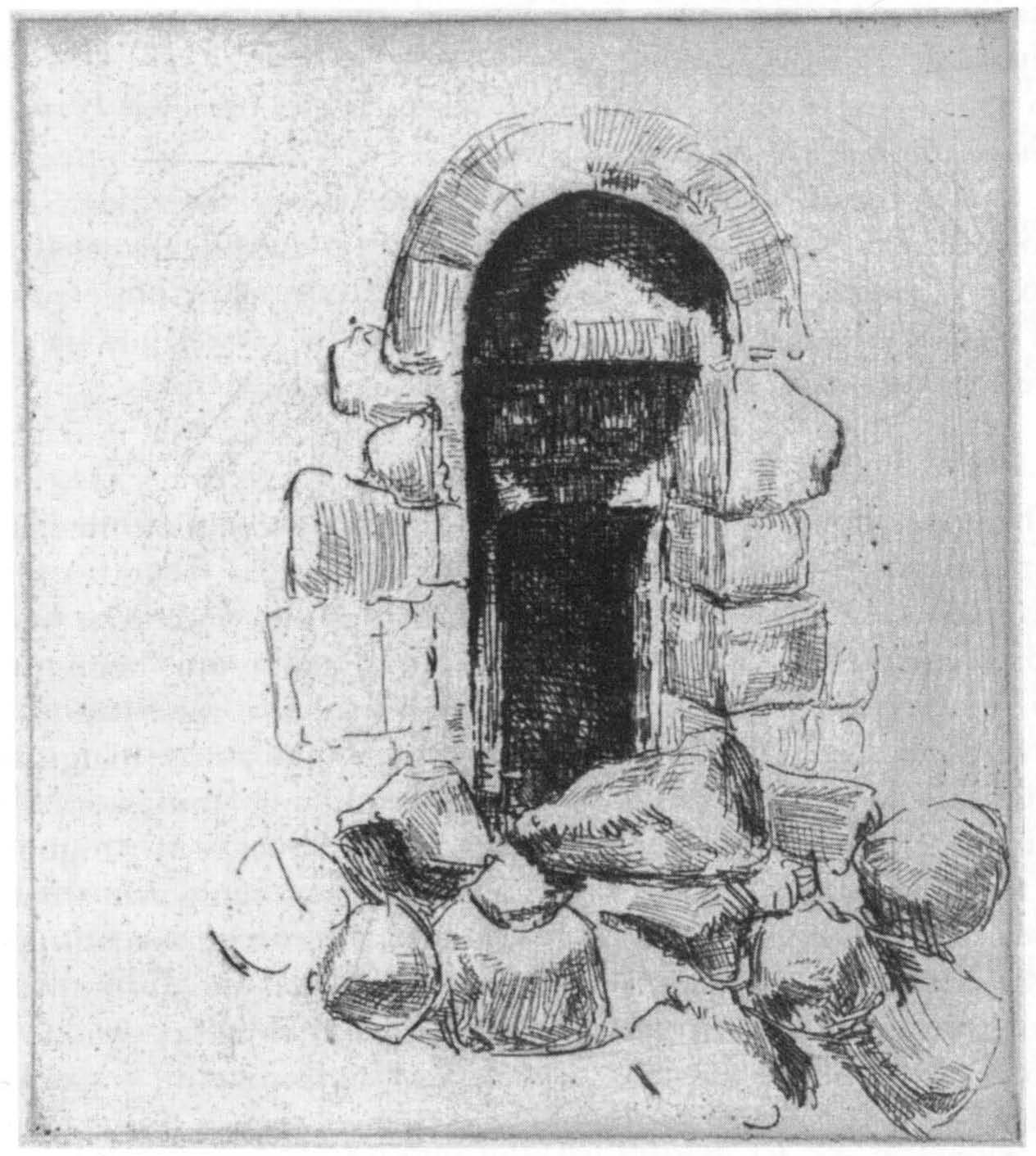

The temple at Baraqish has now been excavated to floor level by an Italian team, but at the time of my visit you had to crawl between the columns with the ceiling a few inches above your back. The building is rectangular and of simple construction, with monolithic square-sectioned columns morticed into the beams which carry the ceiling slabs. Again, the quality of workmanship is outstanding and the limestone joinery executed so faultlessly as to suggest an origin, like that of Classical Greek architecture, in timber building. It pleases the eye in the same way as, say, Shaker furniture.

I went and sat in the shade cast by the nawbah. The guard chucked stones into an empty well while I read an article I had brought, ‘Baraqish According to the Historians’. The old name of Baraqish, Yathill, appears in Strabo’s account of the Roman expedition as ‘Athrula’. Al-Hamdani’s story of the renaming of Yathill runs as follows: the people of Yathill were subjected to a long siege. Their only source of water was a well outside the city walls, connected to the city by a tunnel.* One day the besiegers saw a dog emerging from the tunnel, which they had not noticed before: by following it back, they were able to take control of the city. They renamed it Baraqish, ‘Spotty’, after its betrayer.

By the time I had finished the article, the guard had disappeared and the sun was heading for the escarpment. To the north lay the broad depression of al-Jawf. The ruins of Qarnaw glinted distantly. Then the scene slipped into monochrome, except for a few patches of green in the wadi’s far side that seemed to radiate the last remains of the sunlight.

Ten minutes out of Baraqish on the way back to the Marib road, I stopped the jeep and looked back. The lines of the bastions had disappeared and the city looked like a work of nature – something not built, but dropped on to the plain.

Baraqish, of course, has lost its context. Like Marib, it is surrounded by banks of silt, the remains of ancient field systems. The area covered is tiny compared with the land watered by the old Marib Dam, but it must have provided much of the city’s food. More important is the wider context of the trade routes on which Baraqish, Qarnaw and all the other cities of the ancient South Arabian states were staging posts. These routes were the arteries of Saba, Ma’in, Qataban and Hadramawt, channels for their enormous wealth – wealth generated by tight control of their major commodity: frankincense, the product of the unprepossessing tree Boswellia sacra.

At a very early date, these South Arabian states had become aware of the demand for aromatic gums, as the Pharaonic Egyptians were great burners of incense and consumers of another Arabian product, myrrh, used medicinally and in the mummification process. By the tenth century BC, the Yemenis had been able to develop the overland camel trade with the north, as the visit of the Queen of Sheba/Saba to Solomon shows. The appearance of civilizations in the Fertile Crescent had opened up more markets for aromatics, and in the time of Herodotus no Assyrian lady would make love without first censing herself. Incense-burners from this period, remarkably similar in form to Arabian examples, are found over the whole of the Eastern Mediterranean. But it was the growth of Rome that provided the biggest boost to ancient Yemen’s prosperity. As their empire expanded, the Romans developed a fascination for the Orient and things oriental that became entrenched in society.

Frankincense and myrrh were not the only commodities traded. Cinnamon, for example, was brought from India although the South Arabians managed to keep its source a secret in order to retain their monopoly on its carriage. But frankincense was their principal export, and by leaking selected information or disinformation on production methods, they added to its mystique and its desirability. The Romans were led to believe that the incense groves were guarded by vicious flying serpents which could only be subdued by the smoke of rare plants. It was an early case of advertising hype.

Thus the Mediterranean world viewed the people who produced the fuel for its prayers with the same mixture of awe, envy and incomprehension that the West reserves today for the oil shaykhs who produce the fuel for its motor cars. South Arabia exported an estimated 3,000 tons of incense and 600 tons of myrrh annually. Given that the people of Rome alone spent 85 tons of coined silver a year on incense, that myrrh was vastly more expensive, and that the spices and other luxury goods which passed in transit through South Arabia fetched similarly high prices, the income for the Sabaeans and their neighbours would have compared favourably with the present-day revenues of an oil-exporting state.*

Rome continued to consume the gum of Boswellia sacra until it embraced Christianity and Pauline disapproval blew away the smallest whiff of heathenism. From the end of the second century onwards, the early Church fathers campaigned successfully against the use of incense. A certain amount of backsliding was to occur and incense later found a place in Christian rites, but never at the obsessive level it had reached under the pagans. Besides, the Romans had developed the navigational skills needed to sail down the Red Sea and beyond, bypassing Southern Arabia, and so land routes turned to carrying more prosaic and far less profitable commodities like hides.

In its heyday, most of the incense was brought by boat and raft to Qana – the modern Bir Ali on the Hadramawt coast – from the eastern Hadrami domains where it was grown. The rafts, we are told by the anonymous Graeco-Egyptian author of the first-century navigational guide, The Periplus of the Erythrean Sea, were ‘held up on inflated skins after the manner of the country’. (Such rafts were still to be found off the southern coast of Arabia early last century, when the British Indian naval officer Wellsted noticed fishermen using them in the Kuria Muria Islands.) From Qana the incense was taken inland to the Hadrami capital, Shabwah. Rules governing carriage were stringent, and a reminder of this can be seen in the 180-yard-long wall which blocks the Shabwah route as it passes up a narrow valley, forcing caravans to pass through a single gate. Other checkpoints lined the way for, Pliny says, ‘the laws have made it a capital offence to deviate from the highroad’. At Shabwah, Pliny goes on, a tithe of the incense was taken in honour of the Hadrami god and used for defraying expenses such as the entertainment of strangers. Civil servants and taxes had to be paid, and money found for water and fodder, so that ‘the expense for each camel before it arrives at the shore of our sea [the Mediterranean] is 688 denarii’.

The way to the Romans’ mare nostrum was long – according to Pliny, 2,437,500 paces – and each territory the caravans passed through extracted duty. From Shabwah the caravans, thousands strong and miles long, went via Marib and al-Jawf to Najran. Here the route split, one branch cutting across the peninsula to the head of the Gulf, the other going through al-Madinah and on to Petra for shipment at Gaza or onward carriage to Damascus.

The vital position of Gaza in the incense trade is illustrated by an anecdote in Plutarch’s life of Alexander the Great. Alexander, as a young man, had been ticked off by his tutor Leonidas for burning too much incense in the temple. Years later, when he captured Gaza, he sent Leonidas a message: ‘No longer need you be so stingy towards the gods.’ With the message were thirteen tons of incense and two tons of myrrh.

Trade was two-way. Money, ideas, goods and gods also came to South Arabia from the Eastern Mediterranean. People were imported, too: an inscription of the third century BC in the temple of Athtar (also the name of a Phoenician deity) at Qarnaw, which mentions Gaza no fewer than twenty-eight times, lists details of naturalization requirements for foreign women. Some of the women were Phoenician, others Egyptian or Arab; most came as wives or concubines of Ma’inian men. The God of the Old Testament used the prospect of transportation to Yemen as a threat: ‘I will sell your sons and daughters into the hand of the children of Judah, and they shall sell them to the Sabaeans, to a people far off.’

Individual ancient South Arabians are hard to picture; but disparate clues and a dash of imagination can help sketch the outlines of, say, the life of a well-to-do trader of Baraqish like Zayd Il ibn Zayd, a merchant who exported myrrh and frankincense to Egypt in the mid-third century BC. At this time the Greeks controlled merchant shipping in the Mediterranean, and it was one of their vessels that he boarded in Alexandria to make a tour of the eastern end of the sea. The journey took him to cosmopolitan Delos, where one of his countrymen was later to dedicate an altar with a bilingual South Arabian-Greek inscription to the Ma’inian national god, Wadd. Zayd Il would naturally have looked into frankincense futures before leaving Delos for Gaza, where he picked up a Phoenician concubine to take back to his home town. On a later trip to Egypt he succumbed to the rigours of an international businessman’s life. He was embalmed with his own myrrh and buried in a sarcophagus inscribed with his name and occupation in Ma’inian.

Contemporary Classical writers transmit a fair amount of information on the ancient Arabian peoples, some fabulous but much with a factual basis. Herodotus is the earliest and, as usual, the most entertaining. He wrote that cinnamon was collected from birds’ nests and the gum ladanum from the beards of billy goats; Arabian sheep had such fat tails that they had to trundle them along on little wooden trailers.* Herodotus’s successors are more credible. For example, most of the place-names on Ptolemy’s map of Arabia can be identified at least tentatively and, except for sites far inland like Mara (Marib) and Nagara (Najran), latitudes are little more than fifteen per cent out. The map was not substantially updated until the Niebuhr expedition of the 1760s.

A strange story linking South Arabia, Byzantium and Northern Europe perhaps demonstrates that the Mediterranean world knew something of the celestial nature of early Yemeni religion: the Empress Helena, famous for her search for the True Cross, also sent envoys to Hadramawt. There, in ‘Sessania Adrumetorum’, they discovered the bones of one of the Magi which, after travelling via Constantinople and Milan, finally came to rest in Cologne in 1164.†

The Mediterranean peoples saw the ancient Yemenis only as traders in aromatics and other luxury goods. But to the Yemenis themselves, the cultivation of essential crops was the basis of life. The two gardens at Marib stretched for at least fifteen miles and were clearly a masterpiece of irrigation. Elsewhere, too, enormous effort was put into getting the best out of limited water supplies. Around the Hadrami capital Shabwah, now a barren place on the edge of the desert, some 12,000 acres were under cultivation, while after the Marib Dam the most impressive irrigation works are to be found at Baynun in the central highlands. Here, floodwater was channelled out of its natural course, through tunnels cut in the solid rock of two small mountains, and into a dam. One of the tunnels is still intact, 150 yards long and big enough to drive a car through. Today, many villages of highland Yemen still rely on rainwater collecting tanks that were built two thousand years ago.

As Yemen opened itself increasingly to outsiders over the first few centuries of the Christian era, Arabia Felix was demystified. Sailors from Ptolemaic Egypt had learned to navigate the dangerous shoals of the Red Sea, and the overland trade went into recession. The nomads saw their earnings as guards and camel men plummet, and turned on their former employers by raiding the settled lands of Yemen. The rulers of Himyar – a people whom the genealogists, with their rationalizing minds, traced back to ‘Himyar ibn Saba’ – were now able to use their position in the central highlands, safe from the nomads, to increase their authority; they claimed the title ‘Kings of Saba and Dhu Raydan’, Raydan being the area around their capital, Zafar. Towards the end of the third century AD the Himyari leader Shammar Yuhar’ish had most of present-day Yemen under his control and assumed the title ‘King of Saba, Dhu Raydan, Hadramawt and Yamanat’ – the latter probably the southern coast. But Yemen was to fall prey to the rivalry of superpowers who, acting through satellites, concealed imperialism in ideology.

From the third century onwards, Ethiopian Axumite influence had grown in Yemen; later, there were many converts to Christianity. The backlash was extreme: a Judaized noble, Yusuf As’ar, seized the Himyari throne and began an anti-Christian campaign, resulting in his burning the Christians of Najran. The Axumites thus had their pretext to mount a full-scale expedition to South Arabia. So, in AD 525, began the final eclipse of Yemen’s pre-Islamic civilizations.

Yusuf As’ar (whom the historians call Dhu Nuwas, He of the Ponytail) had ascended the throne by unorthodox means. Nashwan tells us that his predecessor had been warned that he would be killed by the most beautiful youth of Himyar: the king was scornful of the prophecy but took the precaution of having his many handsome young visitors frisked. The power-hungry and good-looking Yusuf, on whom the royal eye inevitably fell, overcame the problem by designing a double-soled sandal. When he was admitted to the royal chambers he got the old king drunk and, like James Bond’s adversary Rosa Klebb, whipped out a stiletto concealed in the sole. He killed his would-be seducer, and proclaimed himself king.

Whatever the truth of Nashwan’s account, other evidence seems to confirm that Yusuf As’ar grabbed the throne in a coup. His come-uppance, following the Najran incident and years of resistance to the Ethiopians, was bathetic. After his final defeat on the shores of the Red Sea he spurred his horse into the waves and was never seen again. So ended the Kingdom of Saba, Dhu Raydan, Hadramawt, Yamanat and – as it had lately been styled – the Arabs of the Highlands and the Lowlands. The most plangent laments on its passing were composed by the blind poet Alqamah ibn Dhi Jadan, known as the Mourner of Himyar. His verse on Duran, a great Himyari castle ravaged by the Axumites, recalls the apocalyptic vision of Babylon:

Himyar and its kings are dead, destroyed by Time;

Duran by the Great Leveller laid waste.

Around its courts the wolves and foxes howl,

And owls dwell there as though it never was.

The Great Leveller had a bizarre end in store for the most famous Axumite ruler of Yemen, Abrahah. At some time after the middle of the sixth century, Abrahah declared himself independent from Axum and assumed the title of the old Himyari kings. He then began trying to divert lucrative pilgrim traffic from Mecca – the major centre of pilgrimage even before Islam – to San’a. When, in AD 570, one of the Meccan family in charge of the Ka’bah passed comment on this policy by defecating in the San’a ecclesia,* Abrahah set off to capture the northern city. He took with him a secret weapon which gave the final battle its name: the Day of the Elephant. Destruction would have been certain for the city of the Ka’bah had events not taken a Hitchcockian twist. Flocks of partridge suddenly appeared and bombarded the Ethiopians with stones, killing all but a few of them. The defeat is commemorated in the Qur’an, and in folklore; the route from San’a to Mecca is still known as the Way of the People of the Elephant, and al-Hasabah, now a suburb of San’a, is said to have been named after the pebbles, hasab, that finished off the remnants of the fleeing Axumite army. Villagers around Amran, north of San’a, say that the small fossilized shells found in the area are the actual projectiles. It is claimed that they fell with such force that they entered through the victims’ skulls and left by their anuses.

Yemeni resistance to Abrahah’s successors coalesced under the Himyari prince Sayf ibn Dhi Yazan. Sayf, however, was too weak to pursue a policy of non-alignment and summoned Persian military assistance. The call resulted in Yemen becoming a Sasanian satrapy. But the rule of these new incomers was short-lived: a new power was rising, inexorably, to the north.

The Prophet Muhammad, born in Mecca in the year of the Day of the Elephant, was dispatching delegates to all corners of Arabia from the new Muslim state in al-Madinah. To San’a he sent Farwah ibn Musayk, a Yemeni who had embraced Islam at the Prophet’s own hand. Muhammad commanded Farwah to spread the new religion, killing those who did not accept it. However, a timely visit by the angel Gabriel, who enjoined Muhammad to ‘show kindness to the children of Saba’, prevented a slaughter. In the event the Yemenis accepted Islam willingly. The Prophet developed a soft spot for them: ‘The people of Yemen’, he said, ‘have the kindest and gentlest hearts of all. Faith is Yemeni, wisdom is Yemeni.’

Nonetheless, there was opposition. In the following year, AH II, a soothsayer named al-Aswad al-Ansi declared himself a prophet and mustered a force of tribesmen whom he led on San’a and Najran. He was defeated and killed by Farwah. Reviled by the Islamic historians, who record that he had a pair of demonic familiars in the form of swine, al-Aswad was later hailed by the PDRY Marxists as a revolutionary. A later false prophet claimed to the tribes of Hamdan that the Archangel Gabriel had also revealed a qur’an to him. As an ecumenical measure he had, too, an Ark of the Covenant, which followed him around on the back of a mule.

Islam swept away the most obvious signs of paganism. The spirit of iconoclasm was at large, and all over Arabia the idols were toppling. As a poet said, ‘Can we call it “Lord” if foxes piss upon its head?’ And as Islam spread, Yemen became politically marginalized. Yemenis had been the spearhead of Islamic expansion; but during the century of Umayyad rule up to AD 750, and then under the Abbasid caliphs, they felt themselves increasingly eclipsed by Arabs of northern origin who came to have more in common with the Byzantines and Persians they had conquered than with their Arabian roots. Yemen’s intellectual counter-attack produced a great treasure of history and poetry. More important, it created for the Yemenis powerful concepts of their own past. In the tenth century, al-Hamdani, known as the Tongue of Yemen, drew on the works of his predecessors and supplemented them with his own research to produce the massive ten-part genealogical and historical compendium al-Iklil. A pioneering antiquary who recorded inscriptions from Baraqish and elsewhere, al-Hamdani was also at heart a romantic who dwelt on the melancholy of ruins and faded glory.

A large section of Iklil VIII is devoted to tombs and their occupants. The most notable feature of al-Hamdani’s deceased ancients, ‘old men dried out upon their beds’, is that they were often buried with an inscription bearing the first half – and sometimes, prophetically, both halves – of the Muslim creed: There is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah. The historian, therefore, is demonstrating the existence of Islam in Yemen before Muhammad – hardly a deviant view, since Islam is the old religion, the faith of Abraham and all the pre-Muhammadan prophets.*

Al-Hamdani, like Nashwan ibn Sa’id, includes many tales of expeditions made by pre-Islamic kings. One, the unbelievably energetic Malik, reached Soghdia, the lands of the Franks and the Saxons, and the shore of the Atlantic where he set up a statue with the warning, ‘He who goes beyond this point will perish.’ Shammar Yuhar’ish, already seen colonizing Tibet, gave his name to Samarqand which, al-Hamdani claims, comes from the Persian Shammar kand – Shammar destroyed it.

It is a history made not by the mind but by the heart. But however wild some of the claims may be, al-Hamdani was insistent on setting them down, for they attempted to show that the armies of Yemen had reached as far as those of Islam. Geographically as well as doctrinally, the sons of Qahtan had got there first.

There are, then, two pasts: the past of the archaeologists and epigraphers, and the more richly embroidered past of al-Hamdani and his school. The two versions are not mutually exclusive; each complements and informs the other. A third past is only beginning to be charted: that of the mass of curious practices inherited from pre-Islamic times. Children in San’a, for example, throw their milk teeth to the sun and call on it to give them the teeth of a gazelle; farmers in some areas butter the horns of a bull when the sorghum is sown, to ensure a good crop; Hadrami townsmen go on annual ibex hunts and present the animal’s thigh and forequarters to the religious authorities – precisely the same cuts that are given to the priest in South Arabian inscriptions and, hardly by coincidence, in both the Book of Leviticus and a Carthaginian tariff found in Marseille.*

And then there is the linguistic past. Arabic, which started as a dialect of North Arabian and had for some time been the lingua franca of trade and poetry, seems to have taken over from the old languages by the end of the third Islamic century. But Yemeni speech is still haunted by the ghosts of South Arabian. Some words have undergone strange metamorphoses as they passed through the twilight areas of meaning between Himyari, Yemeni dialects of Arabic, and standard Arabic. For example, wathan to a Himyari was ‘a boundary marker’; today in some dialects it has taken on the extra meaning of ‘an oath’; in the lexicon, it is ‘an idol of stone or wood’.

This word association came to mind as I travelled alone late one afternoon across the uplands on the way to Khamir. Here is the territory of the Hashid tribal grouping, who have been powerful for nearly two thousand years. Boundary-stones, oaths, idols, were all around. I remembered the Old Testament curses heaped on those who move their neighbours’ landmarks, and the marching lines of little cairns, their shadows lengthening on the bare limestone, suddenly took on an aspect that was ancient and not a little sinister. The way into Dictionary Land is often to be found here, where present and past intersect.

For some Arabs the past is an ephemeral existence on the fringes of desert or sea; for others it begins with the Pharaohs or the Mediterranean of Phoenician and Classical times. Yemen is different: it is one of those rare places where the past is not another country. I have eavesdropped on tribesmen visiting the National Museum and heard them expressing surprise, not at the strangeness of the things they see, but at their familiarity. Asking the way to al-Qalis, the site of Abrahah’s ecclesia in San’a, I have been quoted the Qur’anic account of his defeat on the Day of the Elephant as if it had happened yesterday. There is a feeling in Yemen that the past is ever-present.

The most recent past has been eventful: there has been revolution, war, unification and – as I shall relate – a bizarre and doomed attempt to re-erect the old internal border. At the moment, the future is uncertain and there is a sense, more than ever, of people looking back to the distant past with affection, even with nostalgia. It is appropriate. Nostalgia, as far as the Arabs are concerned, was invented by a Yemeni, the poet Imru al-Qays. The settings of his poetry go beyond the land of Yemen, however, for Imru al-Qays was a scion of the noble sept of the Kindah tribe which transferred to Najd, then to the north of the peninsula. It was he who first addressed the remains of a campsite associated with a past love affair.

Stop. Let us weep, remembering where a love once lodged,

Where the sand hills fall between al-Dakhul and Hawmal …

The tiniest of traces, the atlal – charred sticks, dried goat dung, the minutiae of memory – evoke the deepest passions. ‘In the open plain with its wild, parsimonious beauty,’ wrote Wilfrid Scawen Blunt in The Seven Golden Odes of Pagan Arabia, ‘every bush and stone, every beetle and lizard, every rare track of jerboa, gazelle or ostrich on the sand, becomes of value and is remembered, it may be years afterwards, while the stones of the camp-fire stand black and deserted in testimony of the brief season of love.’

Imru al-Qays, born when the great civilizations of ancient South Arabia were in their final decline, is an appropriate figure to end an account of pre-Islamic Yemen. His life was quixotic and marked by the same combination of wanderlust and homesickness shared by so many other Yemenis of his own time and now. His poetry has become – like so much that originates in Yemen – part of the common cultural inheritance of the Arabs. His obsession, almost Proustian, with the atlal, resembles the Yemenis’ love affair with their past – not so much the concrete past about them, but a past reconstructed from the slenderest historical fact, interpreted not by the mind, but by the heart.

We were taking the short cut to Hadramawt across the sands of Ramlat al-Sab’atayn. It was the way the incense had come from Shabwah to Marib, the route followed by the ancestors of Shaykh Zayid and of my Muscat taxi driver. The Safir oil installation to our left was black against a rising sun. A single flame shot silently upwards. The only sound was the hiss of air from the tyres as Abdulkarim, the desert guide, let them down with a twig to grip the sand better. It would be an easy crossing, he said; the sand was still firm from the autumn rain.

We left the tarmac and crossed the first dune. For a while, we saw the traces of passing humans, an oil-can, a mineral-water bottle: twentieth-century atlal. The desert, though, had kept its looks, beautiful and frightening. For several hours we went on, at first through a sandscape that looked as if it had been formed by a giant ice-cream scoop. Then, gradually, the dunes began to get lower. In places there was the lightest covering of grass, fading blue-green into the distance.

Lulled by the motion of the car over the gentle sand swell, I began to doze. Images of Iram of the Columns, the city of Ad destroyed by divine wrath, flickered, then burst when I opened my eyes. Iram, they said, was somewhere here, in the middle of nowhere, halfway between San’a and Hadramawt.

Suddenly, in front of us, there was a group of buildings.

I sat up and rubbed my eyes. The buildings were still there. Abdulkarim broke a long silence: ‘That’s the old border post.’

He stopped the car and we got out.

The Iram of the Qur’an had been wiped off the face of the earth. The Iram of legend was a mirage, a reaction to the horror vacui of the sands and of history. These buildings were the iram of the dictionary: a marker set up in the desert. As a memorial to imperialism, they are fittingly ugly. And unlike camp-fire traces and oil-cans, it would take many years for their cement blocks to be buried or worn away.

We stood for a while, where the sand hills fell away into the distance, and looked. We remembered, but did not weep.