‘Of this will they assure you, those who know:

Ours is the Green Land – look to the hills!

For the Watchful One blesses them with rain

In times when all His creatures thirst.’

Dhu al-Kala’ al-Himyari (d. AD 1014)

AL-SUKHNAH means ‘Hot’, and the place was living up to its name. A drop of sweat fell from the tip of my nose into my tea with an audible plop. I was too drowsy to mop my face. The torpor was due not so much to the febrile Tihamah night as to the Egyptian soap opera on the TV across the yard. The plot: poor boy, factory worker, falls in love with boss’s daughter … The rest was predictable. Even the calf tethered next to my string bed seemed to be following it. That highly coloured world of gilt what-nots and candy limousines, the 1,001 cliffhangers (camera zooms to startled face) – it’s all been done before, long ago, by the suq storytellers. But it did seem strange in this dun place where the mountains meet the plain.

Al-Sukhnah, though, is no ordinary Tihamah town. The name comes not from the climate but from the hot springs which bubble up at the base of the mountains, and the town dates back only to the days of Imam Ahmad. In his declining years, Ahmad spent an increasing amount of time here, stewing his corpulent frame in water heated by underground fire. Al-Sukhnah was also the setting for his one and only press conference. The journalist David Holden was engrossed by the Imam: ‘His face worked uncontrollably with every utterance, his hands tugged at his black-dyed beard, and his eyes … rolled like white marbles only tenuously anchored to his sallow flesh.’ Again, it was the eyes.

Early that evening I had found the bath in a clump of shabby, block-like buildings. There were three pools of varying temperature, from very hot upwards: the first was just bearable; the second I dipped a toe into; the third was hot enough to boil a lobster. The bath-keeper told me that the temperature varies from season to season. At the moment it was ‘quite cool’.

The waters of al-Sukhnah are said to be good for rheumatism and skin diseases. I had come out of curiosity, and to loosen my limbs for an unrest cure in the mountains of Raymah.

Anyone who had not been there before would need some persuading that Jabal Raymah existed at all. But it was there, invisible behind the post-prandial Tihamah haze. Al-Mansuriyyah market, the departure point for the mountain, was settling down for the afternoon, and potential Raymah passengers were drifting away alarmingly. The Landcruiser taxi would leave only if it was full; earlier, the suq seemed to be packed with Raymis on their way home, but they couldn’t provide a stable quorum and the taxi-driver had spent the last three hours appearing and disappearing with shrieks of differential and clouds of dust, like a jinni in a huff, trying to round them up.

I was the eye of the storm, the queue of one at the taxi stop. Raymis would come and use me as a timetable, getting the latest travel information then dashing off to make some last-minute purchase. All the last minutes mounted up. I should have been recording the manners and customs of Tihamah market-goers, but all I remember is an old man on the pillion of a motor cycle, brandishing a pair of crutches to clear a passage through the crowd. Several people were felled, as if by the scythes on Boudicca’s chariot wheels.

A man was shaking me by the shoulder. I must have dozed off. ‘Come on! You’re holding everybody up.’ He dragged me away by the hand. Waiting for the taxi in an orderly English way I had forgotten that the world, and not least al-Mansuriyyah, was in a state of perpetual flux. To paraphrase the pre-Socratics, you could not stand in the same queue twice.

The man was soon ahead of me. I had the longer legs but while I shuffled, he skipped, the result of a lifetime of mountain paths. Even dressed in a suit and tie, his gait would still have given him away as a mountain man.

The taxi was packed. I followed my acquaintance to a place on the roofrack, but one of the fifteen or so passengers inside was ejected and I was pulled in instead. A woman in the back admonished me when I protested. ‘Shame on you, Professor. Old people like us deserve to travel in comfort.’ She was old enough to be my grandmother.

We were off. The driver selected a cassette and turned the stereo on full. A rhythmic slapping and a noise like a vastly amplified comb and paper, just recognizable as a mizmar, a double reedpipe, came from the single working loudspeaker. We passed the turning to al-Sukhnah, then entered a landscape of carefully pollarded trees and bullrush millet, invaded in places by patches of rock and euphorbia. Ahead, Raymah hovered, a spectral mountain. It rises to over 7,000 feet and is the bulkiest of all the ranges that overlook Tihamah, the ‘Climax Mountains’ on Ptolemy’s map,* but in the afternoon vapours it is on top of you before you have a complete idea of its size. The road became increasingly steep, rounding the bases of huge honeycombed stacks.

After the village of Suq al-Ribat, where we bought qat, the road climbed ever more steeply. On either side, near-vertical slopes were covered with a dense layer of creeper-hung trees, a rare survival of the aboriginal forest which once cloaked the entire range. Rising out of these was the lighter green of inhabited places, pyramidal peaks and dizzyingly steep flanks of mountain. The landscape, seen through a moving frame of windscreen, looked as fanciful as a Chinese watercolour.

Raymah, like much of Yemen, is an upside-down place. In other mountainous countries, people tend to live in the valleys; here in Yemen they seem to choose the most inaccessible ridges and summits for their dwellings, places only fit for eagles. Why? Is it for defence, or because of the climate? Or for the view? Or is it just contrariness of nature that makes them build on seemingly impossible peaks, where calling on the neighbours means a trek of hours along goat paths, and qat sessions are arranged by walkie-talkie?

The defensive argument is strong. Power-hungry outsiders have always lusted after Yemen’s strategic location, for whoever controls its western seaboard controls the entrance to the Red Sea. Time and again, invaders have occupied the coast, where it is easy to land large forces, but have left their backs open to attack by the mountain people. Even the Ottomans, with their advanced weaponry, only effectively held the cities and were for ever busy resisting assaults led from mountain strongholds like Shaharah. They were given little freedom of movement by a tough landscape and a tough people. A sixteenth-century Turkish commander summed up his problems when he said, ‘Never have we seen our army founder as it did in Yemen – every force we sent dissolved like salt.’ Three hundred years later, another Turkish general commented on the mountain tribesmen of al-Haymah that he could take the whole of Europe with a force of a thousand such fighters. Things hardly changed when the Egyptians brought air-power into the anti-Royalist conflict of the 1960s: mobility in the air means nothing if ground forces cannot follow it up.

Retreating to the mountains in time of war is, then, understandable; but to live there permanently, expending so much effort against gravity – why? Perhaps a walk along Raymah would answer the question.

A mizmar tape is hypnotic by the third hearing, and the qat was beginning to take effect when the top came into view. For the last section of the road the driver even used four-wheel drive – to avoid doing so seems to be a point of honour among Yemeni drivers. About three hours after leaving al-Mansuriyyah, we arrived in al-Jabi, the metropolis of Raymah, entering it from beneath the walls of its fort. From here, if you are up early enough, you can see across Tihamah to the sea and, some say, to Africa.

I finished my chew at the lukanda, a corrugated iron flop-house, watching American all-star wrestling on Saudi TV. The picture was soon blotted out by snow on the airwaves, and I went for a stroll in the keen evening air. Stopping for cigarettes, I was impressed by the range of goods in the shop. Mini stereo speakers sat next to air rifles, depilatory cream jostled against tins of lychees.

The shopkeeper was an ex-resident of Jeddah who had left Saudi Arabia before the Gulf crisis in 1990. The Saudis kicked out his less fortunate compatriots, like our host in Wadi Surdud, who were still there when Kuwait was invaded. Up until then they had enjoyed a special status which allowed them to work without finding a Saudi ‘guarantor’. By their reaction to Yemen’s stance on the Kuwait crisis – that all possible efforts should be made to find an Arab solution before calling in non-Arab forces – the Saudis had deprived themselves of a huge part of their service sector and had reduced hundreds of thousands of their Arab brothers and sisters to penury. Many of them reached Yemen with only the possessions they could carry, leaving behind their sole source of livelihood. By early 1991 perhaps a quarter of the cars on Yemen’s roads belonged to these refugees in their own land, and reception camps were crowded and insanitary. The economic backlash has been severe, with huge losses in hard currency income and in aid from the Gulf States and elsewhere, and a massive fall in the value of the riyal. Other poorer Arab states – those which supported the US-led force – were silently paid off by having their debts rescinded. Yemen, however, remains a little-publicized victim of the Gulf crisis, a martyr to conscience in a world of realpolitik.

Back at the lukanda most of the other guests were asleep under the neon striplights, cocooned in tartan blankets like Henry Moore’s sleepers in the Underground. I climbed up a ladder to a broad shelf at the back of the room and fell asleep thinking of the walk that lay ahead.

Nothing in the world, I thought as I started out along the track, sets you up for a walk as well as a plate of steaming fried liver at six in the morning at 7,000 feet. To the left, a small plateau ended in a row of houses and then nothing; to the right there was just nothing, or rather a huge vertical drop ending in a sea of vapour rising from Tihamah. A couple of crowded trucks passed, heading towards al-Jabi.

Shortly after, the motor track began a huge arc round the outer flank of the mountain and I struck off on a well-trodden footpath to cut off the corner. For a while the going was easy; then the path crossed a rock face and became little more than a crack with a long plunge to the left. I picked my way gingerly, sending little avalanches over the edge. A group of young children squeezed past me and skipped along on their way to school in the town, oblivious of the drop.

As the path levelled out I saw that a change had taken place. Away from the seaward-facing slopes the terraces had a different look – they were either bare or, where there were crops, growth was stunted. The contrast was stark, the result of a sudden climatic variation: a detailed weather map of the western mountains would be made up of a patchwork of micro-climates, each dependent on the exact topographical aspect of its location. Raymah weather is certainly strange: I have seen snow in the month of June.

In one of the bare fields an old man was taking a rest from ploughing while his donkey munched alfalfa. The bundle of fodder stood out against the khaki earth like an exclamation mark. The man beckoned me over and poured some qishr, husk coffee, into a tin can; the bite of ginger was instantly refreshing. I asked him, as one does, about the rain.

‘In Kusmah,’ he said, ‘they’ve had some good downpours, but here … well, it has spat a few times this year. We have to get our water from the spring down there,’ he pointed to a patch of green, probably a thousand feet below, ‘and that’s almost dry. We had some water engineers here, but if there’s no rain in the first place there’s nothing for them to engineer.’

It was hard to know what to say. It would have been cold comfort to point out that this was merely another in a series of droughts which, punctuating Yemeni history, have killed thousands. At least, with all the imported wheat around, people would not die as they did just the other side of the Red Sea. ‘Can’t you drill a well?’

The man laughed. ‘The shaykh was trying to collect money, but how can we come up with … oh, a million or more? We were thinking of getting the boy from Ta’izz – do you know the one? He can see water through rock. “Drill here,” he says. “There’s grey rock, then black rock, then water at 400 feet.” And he’s always right, praise God. But you still have to get the machine in and drill.’ He crumbled a lump of earth in his fingers. The wind blew it away before it hit the ground.

‘May God bless you with rain,’ I said, getting up to leave.

‘Amen,’ he replied.

I waved to him before I rounded the mountain. As he raised his arm, the sun caught the brilliant white of his zannah, and I thought of the enormous effort that had been expended in washing it.

Back on the motor track, each step raised a puff of dust as fine as talcum powder. Rocks underfoot were polished smooth by spinning tyres. I stopped in the meagre shade of an overhang, where drill holes showed that the cliff had been dynamited away. My throat was dry and I wondered where I could get water. Then, around a corner, I saw a car parked on the shoulder of the mountain and quickened my pace.

The car was a Layla Alawi, the latest model of Landcruiser which the Yemenis named after a curvaceous Egyptian actress (she was furious). It would have a cooling compartment between the front seats, packed with drinks. A man stood next to it, looking at the view.

I greeted him and was granted a lacklustre reply from the back of his head. He turned in a studied way and, for a moment, I was taken aback by his appearance. Over an immaculate zannah with buttoned Mao collar he was – even in the heat of the sun – wearing a black sheepskin-lined greatcoat, not the usual countryman’s baggy version but cut with a swagger. It was the sort of coat a White Russian prince would wear. In his belt, behind a vastly expensive jambiyah, was a chrome-plated Smith and Wesson with ivory grips. A perfectly trimmed moustache swooped down to sharp points on either side of his chin. He looked like Lee Van Cleef after a successful night at the poker table.

‘Er … Have you got any water?’

The man paused to think. ‘No.’

‘Is there anywhere I can get some?’

He was looking at my ancient, fly- and mildew-spotted rucksack. ‘No.’

For a time I surveyed the view. I had never met anything like such a stony response in Yemen. Well, I would engage him in conversation. ‘Not much rain, is there.’

He clicked a Yes.

Silence.

‘Are you from al-Jabi?’

He clicked a No.

‘Kusmah?’

A shake of the head.

‘So … where are you from?’

‘Bani Abu al-Dayf,’ he said, with a pained sigh.

An unusual name. Rendered literally, The Sons of the Father of the Guest. I couldn’t resist. ‘Ah, you must have been called that because of your hospitality to passing strangers.’

He burst out laughing. The pose was gone. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said, ‘but I really haven’t got any water.’

We said goodbye. Someone I met on the road later knew the man with the Layla Alawi and said that he’d made a killing in Riyadh, running a juice bar.

It was lunchtime. The two or three villages I passed showed no signs of activity. They sat on outcrops, ringed by dense barriers of prickly pears. These, although they are found all over the country, are not native to Yemen, as their Arabic name – ‘Turkish figs’ – suggests. (In Greece they are called ‘Frankish figs’ and the scientific name, Opuntia ficus-indica, proposes yet another origin; in fact, they came from the Americas.) But they are welcome invaders, for their fruit is wonderfully refreshing.

I turned on to another footpath. By now the humidity boiling off Tihamah had risen enough to cut out the harshest rays of the sun. Another vista opened, and another micro-climatic region. This time it was moist, and there were even some mushrooms. It was tempting to lie down, surrounded by rising cloud and the scent of thyme; but Kusmah, the day’s destination, was still a long way off.

Back on the path, a boy overtook me. I caught up with him and kept pace for a while. Then, suddenly he stopped and gazed intently to his right. I couldn’t see what was holding his attention until he picked up a stone and flung it. Something tumbled over the little terrace wall. A long, thin tail twitched. A chameleon. It tried to get up but he threw another rock which caught it in the middle and it lay still, its visible eye revolving feebly. I like to think that it may have changed colour, gone through its palette in a chromatic swan-song, but we pushed on. I soon realized I could not keep up with the boy, who was about ten, and told him to go ahead. Later, I met him coming back from the market below Kusmah. It was still half an hour away but he had been there, done some shopping, and was on his way home. I began to feel that the old woman in the taxi to al-Jabi might have had a point.

In the market I was collared by a voluble and slightly crazy old man who gave me a run-down on the US election campaign. He lost me when he got on to the relative importance of the various primaries. The sun was going down, the mist was coming up, and I abandoned him in Iowa. My knees were crying out for the horizontal, but I set out for the final pull up to Kusmah. At first I tried to keep up with the last in a string of donkeys carrying sacks up from the market. As it climbed, it farted rhythmically inches from my nose and it was a double relief to get to a level stretch of path.* Kusmah is built on a ridge at the south-western end of the Raymah massif. From below it has an imposing presence; when you get there it is a pretty ordinary large village, with one irregularly cobbled street lined with shops, all selling the same things. Gaps between the buildings open on to distant views over the Kusmah midden and the prickly pears that thrive on it. I made for the single eating house and ordered a plate of beans as the sunset prayer was called. With a cough, a generator cranked into action and the striplights flickered on. The clink of tea glasses, the hiss of the paraffin stove, the thud of the generator – all were sounds of arrival in a mountain town. The breath of donkeys hung in the air outside.

There were two people in Kusmah I was keen not to bump into. The first was the self-styled umdah, or mayor. On an earlier visit I had spent a couple of hours in his house at the top end of the ridge, and the entire time had been taken up with his prostate trouble. I was willing to forgo a further session on the mayor’s leaky plumbing. As I sipped my tea, the other major annoyance of Kusmah stalked past in his striped pyjamas, stately in a pained sort of way. I quickly stared into my beans. After my previous escape from the umdah I was passing the school when this man, graduate of a university in the Nile Delta and Kusmah’s principal pedagogue, had shot – if that’s the right word for a fat, middle-aged Egyptian – out of his religious instruction class and dragged me in. I was a choice and appropriate piece of what the theorists of teaching call realia, educational objets trouvés.

Fifty pairs of eyes were on me.

‘What is your name, sir?’ the Egyptian asked in English.

‘Tim.’

‘No! “My name is Tim.” ’

‘Oh, yes. Sorry. My name is Tim.’

‘And where are you from, Professor Tim?’ He rolled his r’s like a big car purring.

The interrogation continued in English. The children, of course, understood nothing. Nor were they supposed to: they were a primary class, and English instruction is only given in middle and secondary schools. After establishing my basic credentials of nationality, marital status, religion and so on, he changed into Arabic.

‘Come here, Ali.’

A small boy in the front row jumped up. Teacher’s pet, I thought. The Egyptian put one arm round each of us – with some difficulty because of the vast difference in height – and stood beaming. The room was in suspense.

‘Now. How many eyes has Professor Tim got?’ he asked the class.

‘Two!’ they shouted.

‘And how many eyes has Professor Ali got?’

‘Two!’

‘How many ears has Professor Tim got?’

‘Two!’

‘And Professor Ali?’

‘TWO!’

‘How many … noses has Professor Tim got?’

‘One!’ There were a few ‘twos’ from the back of the class.

The questioning went on until we had covered all mentionable parts of the body. Our respective religions were then re-established. ‘So, although Professor Tim is a Christian and Professor Ali is a Muslim, God has created them the same in all respects.’

‘But he’s taller!’

‘Silence! This’, said the Egyptian, finally releasing us, ‘is proof of the oneness of His creation.’

A bell rang and the pupils charged out. I admired the teacher’s exposition of so elemental a truth, and told him so. ‘Naturally’, he said, ‘we must use such methods here. The people are so very … simple.’

I said that, to me, the pupils seemed very bright, that school education to them was something new and that, moreover, it was appreciated far more than in the West. And in Egypt, I nearly added. I could have done – he wasn’t listening anyway. But then I didn’t pay attention to his tirade against life in Kusmah compared with the pleasures of Tantah. For an Arab returning to the cradle of his race – and getting paid vast sums of money relative to his potential earnings at home – it all seemed ungrateful.

Well-meaning people in Yemeni villages have often billeted me on a teacher with whom, they suppose, I will have much in common. With Egyptians the reverse is true. It is different, though, when the teacher is Sudanese. Although their spindly Nilotic forms – Giacometti men clad in robes of purest white – are more suited to the wide savannah than to the mountains, all the Sudanese I have met seem to have an affinity for Yemen and its people. And when they get together the Sudanese party, unlike the lugubrious Egyptians and their homesickness encounter groups.

I looked up from my beans, paid and left. Outside, I glimpsed the teacher’s broad back nearing the end of the street, the turning-point of his solitary paseo, and for a moment I felt sorry for him. But I went quickly to the funduq, found a room to myself and, undisturbed except for a tiny girl who appeared cat-like round the door and asked me if I was an Egyptian, read for a while then fell asleep.

Kusmah is on the watershed, and another climatic border. From here to al-Hadiyah, my final destination, was a hard day’s walk. There was no motor track, but there was at least the prospect of well-made footpaths.

The path zigzagged down the flank of the mountain. It was heavily scented and slippery with dew. I passed a party of women on their way to collect fodder for their cattle: many of the mountain women keep at least one cow, which gives them a degree of economic independence. The money they make will usually be turned into gold, and these women were well off – their heavy chokers and large pendants, swinging against flared dresses of Japanese synthetic brocade, caught the sun as it rose over the mountain tops. People looked prosperous, and it was good to see houses being built in every village.

The track crossed a dry stream bed then turned to follow the side of a mountain mass set at right angles to that of Kusmah. Villages clung to the steep slope all the way along it and from now on the path was beautifully built, of large stone blocks fitted together in a careful jigsaw pattern. Fresh donkey dung everywhere showed that this was a principal highway.

The path wound for much of the way between high stone walls enclosing terraces. They were overhung with coffee trees and ferns, and gave the place a churchyard feel. Now and again, water channels opened up on the left to give views of the great sugarloaf of Jabal Zalamlam. Then the path dropped down into a deep valley scattered with houses, their window ledges glowing with the autumnal colours of drying coffee berries.

Coffee has a special place in the Yemeni’s heart. As a modern symbol for Arabia Felix, the coffee tree appears on stamps and bank notes. The anti-qat lobby makes the largely unjustifiable charge that coffee trees have been rooted up to be replaced by the more valuable crop, but optimum growing requirements for the two trees are different. Certainly, though, the heyday of coffee production is over. As early as 1738 an English traveller in Egypt noted that Yemeni coffee was being adulterated with cheaper beans from the West and East Indies. The Yemenis themselves have always sold the beans, bunn, and drunk qishr, made from the husk.*

If coffee used to be the prime export crop, the staple for home consumption has always been grain, as traditional dishes show. There are scores of bread varieties, and these are used in dips, like saltah, or to soak up broth, milk or ghee. Porridge- or polenta-like dishes such as asid or harish are common. Within a limited but delicious range, the Yemenis are connoisseurs of food, suffering the furnace heat of a crowded eating house that makes the best saltah, or queuing – sometimes for hours – for special sabaya bread during Ramadan. Before qat caught on (probably in the fourteenth or fifteenth century) food seems to have been the national obsession. Ibn al-Mujawir says: ‘Their talk is of nothing but food. One will say to another, “What did you have for breakfast?” and he replies, “Millet bread with two kinds of milk,” or, “Layered bread and oil.” Another asks, “What did you eat for supper?” and his friend replies, “A round of wheat bread and four fils-worth of sweets – altogether it came to six fils!” Or you will hear someone say, “I’ve eaten enough today to last me three days! Bread and milk and sugar candy – I gorged myself until I was bursting …” ’

Sorghum is the most widely grown cereal, and has been since ancient times: the names of the different varieties derive from those of the old South Arabian seasons. Life itself turns on the harvest, surab (another pre-Arabic term), as the bachelor’s prayer shows: ‘Be patient, O my prick, until the harvest, or I’ll chop you off!’ To pay the bride-price would be impossible without the money generated by a good crop.

Another legacy of the so-called Age of Ignorance before Islam is the widespread use of star lore, by which farmers overcome the problem of the lunar Islamic months being out of step with the farming calendar. The rising of certain stars divides the seasons, and in some places ancient rock gnomons are used to calculate sowing times. Another rich source of farming lore is the collection of verses of Ali ibn Zayid. Star lore in particular has been formalized, often versified in mnemonic form to give information like when to cut wood so it won’t get wormy, and when the fleas will start jumping – as if one needed to know.

The minutiae of astral calendars fascinated the inquiring minds of the Rasulid rulers. They were both patrons of science and scientists themselves, and married local star lore with the latest international developments in astronomy. Their heritage is very much alive, and a number of astral calendars are in print today. In terms of varieties grown, Rasulid rule also marked the golden age of Yemeni agriculture, and the sultans imported fruit trees, herbs and flowers from as far away as Sind. A contemporary list of products includes exotica like cannabis and asparagus. Their passion for all things agricultural took off at Sabt al-Subut, a date festival centred on Zabid which reached Bavarian Bierfest proportions. People came from all over the country to drink wine made from dates and wheat flour, and to be entertained al fresco beneath the palms by three hundred camel litters full of dancing girls. The bash lasted for weeks and ended with the revellers going to the sea on bejewelled camels for a mixed bathing session. As a result there were, Ibn al-Mujawir says; ‘many divorces and many marriages’.

Coffee, a more sober crop, is associated with the Sufi mystic al-Shadhili, founder of the modern town of al-Makha. He is reputed to have introduced it from Ethiopia in the early fifteenth century and made use of its stimulant properties to spend more time in prayer and contemplation. In Yemen it has never attracted the faintly racy image that went with the London coffee-house or the espresso bars of the 1950s, although elsewhere in Arabia some of the more extreme members of the puritanical Wahhabi sect have disapproved of its aroma of unorthodoxy.

Some women called me over from the yard of their house in the valley bottom. There were no men about and, although they were far from nubile, I sat at a demure distance on a wall. One of the women went inside the house while the other went on feeding a cow.

‘Come on, my dear, eat,’ she said, coaxing a bundle of dry sorghum stalks wrapped in greenery into the cow’s mouth.

‘Can’t she see it’s a trick,’ I asked, ‘I mean wrapping up the sorghum like that?’

‘Oh, she knows. But if you don’t do it she’ll eat nothing at all. It’s a game.’ The woman held an unwrapped stalk out to the cow. It shook its head like a truculent child.

The other woman appeared with a tin bowl full of qishr. All around, on large metal trays, coffee beans lay in the sun. I remembered The Dispute between Coffee and Qat, a literary contest composed in the middle of the last century in which each tree vies with the other in praising itself and belittling its opponent. The coffee tree says: ‘When my berries appear, their green is like ringstones of emerald or turquoise. Their colour as they ripen is the yellow of golden amber necklaces. And when they are fully ripe they are as red as rare carnelian, or ruby or coral.’ The nearest jar of Nescafé was far away.*

I said goodbye and set off on the track, which zigzagged up one of those stegasaurus backs like the one we had crossed in Surdud. I was still panting when I got to the yard-wide ridge. I hung my jacket on a prickly pear and sat down. Two men appeared from the direction of a solitary tower further down the ridge. They were dressed in spotless white zannahs, lounge-suit jackets and highly polished loafers. Not a bead of sweat showed on their faces. They greeted me without stopping, leaving behind them a strong scent of rosewater. The scent was still there when I looked up to the left ten minutes later. The men were far above, white flecks moving against the dark green of the mountain.

In an hour or so (a great deal of effort is compressed into those five monosyllables) I reached a village, unimaginatively – if appropriately – named al-Jabal, the Mountain. I propped myself up against a shop doorway and gulped down a can of ginger beer. Flavoured with chemicals resulting from decades of research, packed in al-Hudaydah under franchise from a German firm in a can made from the product of a Latin American bauxite mine, furnished with a ring-pull which was the chance brainchild of a millionaire inventor, and brought here by truck, then donkey, for my delectation, it wasn’t nearly as refreshing as the qishr. The ground was strewn with empty cans, each saying in Arabic and English ‘Keep your country tidy’, and I wondered for a moment whether to put mine in my rucksack until I found a litter bin; but the nearest one was several days away, so I placed it at one end of the counter. The shopkeeper picked it up and threw it on the ground.

From al-Jabal to al-Hadiyah is downhill. At first the path was covered with rubbish, but soon there was just the odd sweet wrapper or juice carton as a reminder of the world of creation and corruption. The afternoon cloud rose, swirling past at speed, forced upwards by the cooling of Tihamah and channelled between the sides of the gorge. Everything but the rock wall either side of the path was cut off and I walked in silence. It was like swimming. Only once was the silence broken, by girls’ voices singing a snatch of antiphony as they gathered fodder high above on the cliffs. The last note of each phrase was held, then let out with a strange downward portamento, like an expiring squeezebox.

About half an hour out of al-Jabal, a strange thing happened. For perhaps a minute the cloud parted, revealing two conical peaks directly in front and, below, a field of cropped turf, like a green on a golf course and perfectly circular. Then another column of cloud rose and shut out the vision. The precise geometry of the field’s shape and its vivid colour, and the way in which it had been revealed so unexpectedly and then veiled over, made it a mysterious sight. It had seemed to hover. It was the sort of place where you might bump into al-Khadir, the Green Man.*

I half thought I had imagined the field and that the path would continue prosaically downwards, but I soon reached it. Once on it the perspective was different and its shape not apparent, a trompe-l’oeil but seen too close to work. A few cattle lay round the margin of the field. They took no notice as I stood watching them and seemed anchored to the ground, oblivious of the intruder in their tiny, circular paradise.

After the field, the mist gradually disappeared and the other-worldliness was gone. Once more the path was beautifully maintained – it had to be, for it passed through an unbroken string of hamlets and carried a constant traffic of heavily laden donkeys. The boys who drove them had their zannahs hitched up and tucked behind their daggers. I stumbled down; so did the donkeys – but at twice the speed; the boys danced on stork-thin legs. Even the ones coming up danced.

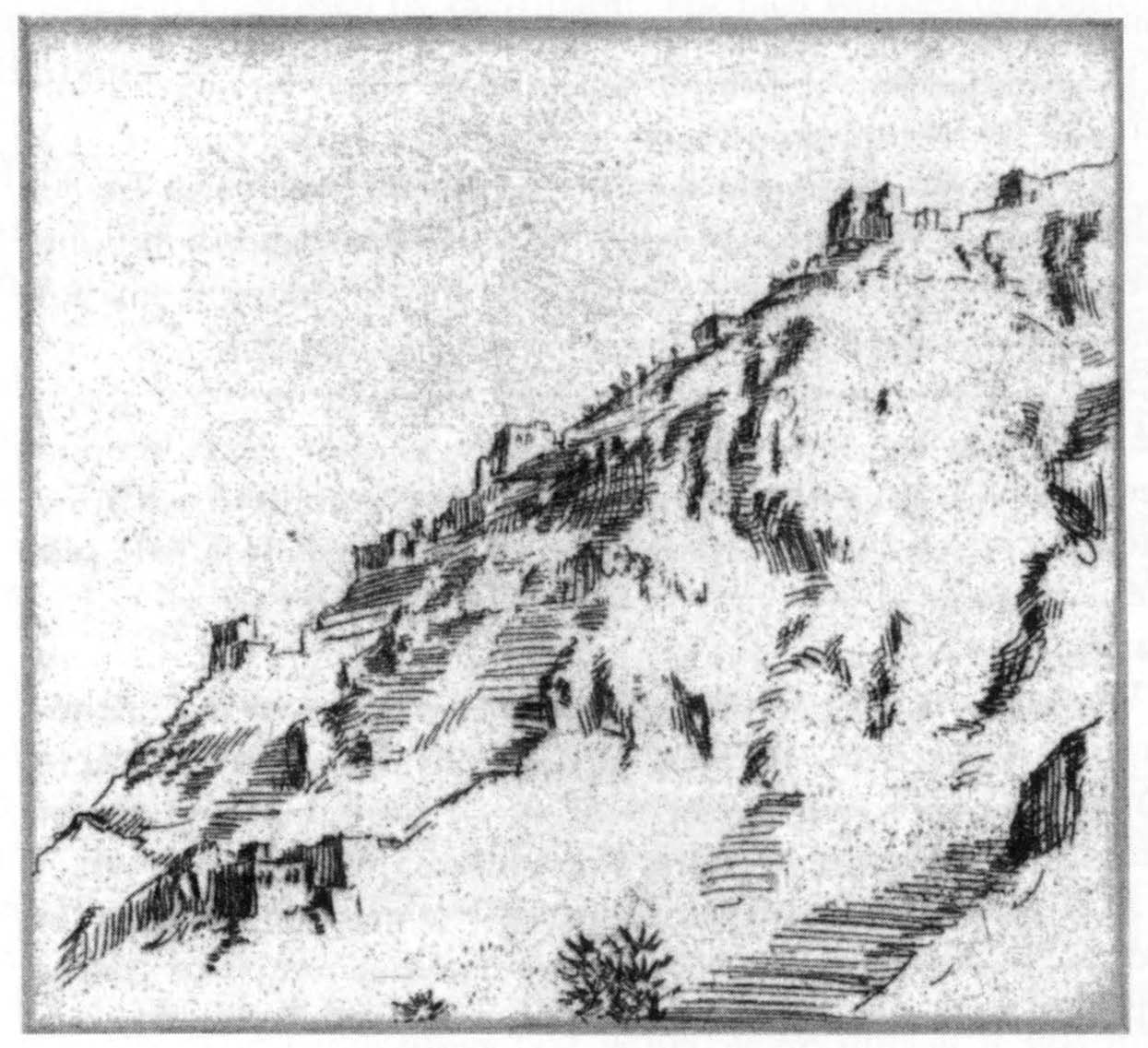

I stopped to rest, and to look at the vista of receding mountain flanks sprinkled with little houses. Somewhere on this very path, Baurenfeind, the artist of the Niebuhr expedition, had stopped more than two centuries before to sketch the original drawings for the plate, ‘Prospect among the Coffee Mountains’. It was the expedition’s first experience of highland Yemen, and they were captivated by the scenery, the people and the flora. The coffee trees, Niebuhr wrote, were in blossom and ‘exhaled an exquisitely agreeable perfume’. It was a landscape in which, despite its natural ruggedness, the hand of Man could be seen everywhere.

Niebuhr’s original Beschreibung von Arabien was at first ignored; but the French and then the English translations were hugely popular when they came out some years later. They had touched the spirit of the new age – the age of burgeoning Romanticism and the Picturesque. Up to then, the reading public had been given an Orient almost entirely of the imagination, colourful but savage. Now Europe began to look at the East through new eyes: Southey wrote of a garden ‘whose delightful air/ Was mild and fragrant as the evening wind/ Passing in summer o’er the coffee-groves/ Of Yemen’; George Moore, in Lalla Rookh, of ‘the fresh nymphs bounding o’er Yemen’s mounts’. They had read their Niebuhr. Baurenfeind’s plates, too, contributed to the new way in which people looked at mountains. Hitherto, mountains had been forbidding places, ignored or feared. Baurenfeind recorded a different image, of mountains dotted with folly-like dwellings, sculpted into terraces and covered with crops – in a word, humanized.

The light was beginning to go and the mountains were turning to amber, then carnelian. The humidity was increasing. The path levelled out and entered a wadi, snaking along the side of the valley through banana terraces which resembled a Rousseau jungle. I was half expecting to glimpse the shade of Baurenfeind sketching from a terrace wall, and when an old woman called out to me from above the path, I jumped. She laughed, and offered me some mouth-snuff. I was tempted but, not being used to it, didn’t want to find myself retching for the sake of a quick nicotine fix.

After the airy peaks of Raymah, al-Hadiyah smelt fetid and unhealthy, although in Niebuhr’s day it had been something of a hill-station for the European coffee merchants, a retreat from the even clammier heat of Bayt al-Faqih down on the plain. (The latter was sometimes rendered in English as ‘Beetle-fuckee’ – probably a reflection of the merchants’ feelings towards it rather than simple bad spelling.) I arrived in al-Hadiyah just after dark, knees jellified by the relentless descent from al-Jabal. I had arranged to stay in the English midwife’s house; she had left the key with her neighbours as she was away – something of a relief, since it would save a lot of tongue-wagging.

The electricity went off early, interrupting me as I flicked through Diarrhoea Dialogue, the only reading material I could find in the house apart from Where There Is No Doctor – a book no hypochondriac should ever open, for its refuses to mince the strong meat of medical problems from leprosy to yaws. I made up a bed on the roof. A frog croaked softly from a pot of geraniums; elsewhere, geckoes clicked; and the night was alive with other, unidentifiable, susurrations.

Not long after dawn the flies woke me. No trucks would leave for Bayt al-Faqih until later, so I walked to al-Hadiyah’s main attraction, the waterfall. This plunges over a cliff in a single dizzy drop, then cascades in a series of deep pools. The path to it wriggled through rocky undergrowth and was home to dozens of glossy black millipedes; some were nearly a foot long and looked like pieces of self-propelled hosepipe.

When I reached the waterfall I found it empty. Little more than a dribble of moisture stained the rock. Only when it rained on the high places would the waterfall come to life, a roaring column of white against the dark cliff.

I sat there watching the dragonflies and thought of my absent hostess, delivering babies up in the mountains where the waterfall had its source. Horizontally she was no distance away; vertically, she was in a different world where climate, crops, dress, buildings, even speech, were different from those of al-Hadiyah. Any study, agricultural, ethnographic or dialectological, of Yemen’s mountains would have to use a three-dimensional projection to map these variations. But in spite of the contrasts encountered over the vertical, the mountain people are bound together by a tenuous lifeline of water.

Rain for the Arabs is barakah, a blessing; and it is particularly so for Yemen where the great majority of cultivable land is rain-fed. In poetry, rain is a metaphor for human as well as divine generosity; historically, water is the reward of just government, and drought the punishment for profligacy. The beneficent rule of Imam al-Mutawakkil Isma’il in the mid-seventeenth century caused an increase in the water table, and even British policy in Hadramawt was said to have resulted in heavy rains there in 1937 (followed, it should be noted, by seven years of drought and famine); in contrast, Imam al-Mansur Ali – he of the donkey-pizzle aphrodisiac – made the wells run dry.

Barakah is for God to grant or withhold, but intercession can pay off. When there is no rain, the entire male population climbs to the high places and starts a litany – ‘Give us rain, O God. Have mercy on us, O God. Have mercy on the dumb beasts, thirsty for water, hungry for fodder.’ A sacrifice is made and left to the birds of the air.* And if the rain comes, they do everything possible to hold it back. This is the function of the terraces which are so much a feature of the Yemeni landscape.

Yemen’s terraces, its hanging gardens, contouring voluptuously round the flanks of mountains or perched, sometimes dinner-table sized, in what are often no more than vertical fissures, are not just a way of making a level surface. More important, they act like a cross between the pores of a giant sponge and the locks of a canal. The rain is trapped by them and contained in subdivisions separated by little bunds, before being released to the next level down in a slow and measured cascade. In slowing the downward flow of rainwater, too, terracing enables more of the wadi land to be cultivated. A torrential downpour, unchecked, runs away to waste and takes with it the wadi’s precious topsoil. The mountain men, as masters of the whole system, tend also to own the valleys and farm them out to sharecroppers. It is a system that calls for continual maintenance. The collapse of one terrace will affect the flow of water, and this in turn will lead to the destruction of terraces further down. Terraces must be kept planted so that the roots of plants consolidate the soil. The delicate balance can also be upset by the building of a surfaced road, which will speed up the flow of water and force streams into new channels.

People have to live at the top. If they didn’t, the upper reaches of the wadis would also be uninhabitable, and cultivable land restricted to a few central plateaux, the hot and malarial coastal regions, and great inland wadis like Hadramawt and al-Jawf. The mountains would in time be stripped bare from top to bottom. Since the protective covering of forests was felled, the history of mountain Yemen has been that of a war waged against loss of land. The weather is, at the same time, the mountain farmer’s reason for being and his antagonist.

And what an antagonist! Millions of tons of water, sizzled out of the Red Sea, fried off Tihamah, bounced up the wall of the escarpment and colliding with the cold highland air, pour down on Milhan, Hufash, Bura’, Raymah and the Two Wusabs. Evaporation and potential energy; blessing and destruction. This is why the Raymis live like eagles, why Yemen looks like nowhere else on Earth.

Gazing up at the terraces hanging all around above me, this ultimate symbol of the Yemenis’ co-existence with their land, I began to understand why al-Hamdani and the other geo-genealogists had turned mountains into ancestors. Lineage seems to have been relatively unimportant in pre-Islamic Yemen. It was the North Arabians, the rootless nomads, who developed the science of genealogy to give themselves a sense of continuity. At the same time, they looked down on settled farmers as peasants, with all the scorn that the word implies. As Islam spread over the Near East, the desert Arabs came across huge populations of settled serfs, in Egypt and the Fertile Crescent, working land which was not theirs.

Yemen was different. Here, the old civilizations had been based on agriculture. When these broke up, settlers moved further and further into the mountains, cutting down ancient forests and terracing the slopes. They were owner-occupiers, yeomen not serfs; and they still are – Yemen has remarkably few big landowners. Ali ibn Zayid, the Yemeni Hesiod, summed up their feelings: ‘The tribesman’s glory is the soil of his home.’ Pride for the Yemenis is in land, not lineage.

To express these feelings and demonstrate the antiquity of the link between land and people – perhaps even to make a political point, that Yemen refused to be marginalized by a super-culture which idealized desert values – al-Hamdani and his school used the super-culture’s own idiom: genealogy. By making placenames the names of ancestors, they were literally planting the Qahtani family tree in the soil of Arabia Felix. It was an extraordinary landscape that they depicted, and – like the corner of it shown in Baurenfeind’s plate – the most remarkable thing about it was the way in which it had been humanized.

And yet, for the West, the nineteenth century created a different image of Arabia. Explorers like Burton and Palgrave – and, more recently, the neo-Victorian Thesiger – portrayed a landscape of sterile sand where only individual qualities of honour and courage could ensure survival. Desert values were resurrected and romanticized, and they struck a chord with Europeans of a more puritan age. The chord still reverberates; received images have crowded out this other Arabia.

I wandered round al-Hadiyah suq and sat for a while at the base of a huge tree. Its exposed roots formed a knobbly bench, burnished by generations of backsides. The tree, a Ficus vasta Forsk., was of great age; perhaps Niebuhr, Forskaal and their companions had sat there, too, and botanized. It was lunchtime when I found a truck to Bayt al-Faqih. I sat chewing qat, wedged between sacks of coffee on the cab roof. Down in hornbill country we passed a group of women whose faces were stained yellow with turmeric. They wore fake plaits made of hanks of wool, and purple straw hats the size of teacups were perched over their foreheads. I glanced back at them and noticed that Raymah was gone, melted into the mist.