‘There were giants in the earth in those days.’

Genesis 6, v.4

IF ADEN SETS its face longingly seaward, then Hadramawt is a Janus of a place, a land of schizoid tendencies. There is an endless, crab-infested strand looking out to the ocean, where Mombasa and Mangalore, Surabaya and the Celebes, are only a monsoon away And there is another parallel, interior world, Wadi Hadramawt, Hadramawt proper, introspective, separated from the coast by a five-hour drive across empty country.

The early start for the Wadi turned out to be a waste of time, and it took until mid-afternoon for the taxi to fill up. Did no one ever go there? Or did they all fly? The al-Yemda airline office here in al-Mukalla had been packed with would-be travellers trying to get their names inscribed in hefty ledgers, and by the time I got to the front of the queue the plane was full. In a way I was not disappointed: the calligraphic logos that looped across the walls – Just as a swimmer needs a lifebelt, the air traveller needs Al-Yemda – were not reassuring. Al-Yemda, in these post-Marxist times, could do with the services of a decent copywriter.

I had read Freya Stark’s account of languishing in Hadrami parlours with measles exacerbated, according to her streams of lady visitors, by washing with soap. I had also read Harold Ingrams’s story of how he pacified a region where recent history included all the storybook elements of savagery: slaughters at feasts, massacres by slave-soldiers, decade-long sieges where people made their sandals into soup. Ingrams arrived in Hadramawt to find some two thousand soi-disant independent political entities. (And the French are supposed to have a hard time governing a country which has 246 different types of cheese.)

After some hours of inactivity I opened the book I had brought, The History for Those Who Would Perceive Clearly by Ibn al-Mujawir, at the section on Hadramawt. It was a mistake.

‘In the world of coming-to-be and passing-away, there is not a rougher people than the Hadramis, nor a race that exceeds them in evil and lack of goodness. They continually find fault in each other and will offer little protection to those who seek it from them. The blood of the slaughtered is everywhere … Because of this, Hadramawt is called The Valley of Ill-Fortune.’ He adds that the Hadramis live on nothing but dried sprats, oil and milk, and that they dye their clothes with green vitriol. The women arrange their hair in a crest, like a hoopoe’s.

Worse, ‘All the women of these parts are witches. If a woman wishes to learn the most complete magic ever witnessed, she takes a human and cooks him until he dissolves and his flesh turns to gravy. When the gravy is cold she drinks it all up, thus becoming pregnant. She gives birth seven months later to a monstrous human called an afw. This resembles a cat in length and breadth, but its generative organ is the same size as that of the large afw, the foal of a donkey. The witch takes it around with her wherever she goes and trains it until it has grown big and strong. Then, when it is mature, it copulates with its mother … [here the text is corrupt]. The afw can only see its mother/wife, and is itself visible to none but her.’

Blood, vitriol and priapic-Oedipal familiar spirits. When at last the taxi left, I said farewell to al-Mukalla with a sense of fore-boding.

Hadramawt, for outsiders, was harder to reach even than the mountains of north-western Yemen. For information on its coast Hunter, writing in 1877, refers his readers to Ptolemy. The interior was a blank on the map. Probably the first Westerners to see the Wadi itself were Antonio de Montserrat and Pedro Páez, two Jesuits captured in 1590 near the Kuria Muria Islands while on a mission from Goa to the court of the Negus in Abyssinia. The next European visitor did not arrive for another 250 years, when Adolf von Wrede, a Bavarian baron, succeeded in reaching the branch wadi of Daw’an; there his baggage was stolen and he turned back for the coast. Von Wrede made many astonishing claims; for example, trying to measure the depth of a patch of quicksand, his 60-fathom plumbline sank without trace. Ridiculed, he emigrated to Texas and later appears to have killed himself. He was followed in the 1890s by Theodore and Mabel Bent,* then from the 1930s onwards by a handful of Arabists, explorers and administrators. During the Marxist period Hadramawt saw some joint Yemeni-Soviet archaeological activity and a few tourists, shepherded closely and at great expense.

The other passengers were silent and showed no interest in the passing landscape. No one spoke to me. Perhaps, in Hadramawt, where in this most conservative of societies the Marxist regime had been most oppressive, they hadn’t realized that talking to foreigners had been decriminalized. But then, my fellow travellers hardly spoke to each other. Stranger still, for a people who had colonized everywhere from the Swahili coast to the Philippines, they were not good travellers. As the taxi began to climb the escarpment that overlooks the coastal plain, the man next to me stopped the car to get out and vomit. Shortly afterwards the man on my other side expressed his solidarity, this time into a plastic bag. For the rest of the journey they sat with towels round their heads.

At the top of the pass, a strange landscape unrolled, something like the Yorkshire Moors minus the topsoil. This was the jawl. Just as al-Madinah is enlightened and the Aegean wine-dark, the jawl has its own epithet in the accounts of all who describe it: barren. It is often called a plateau, hardly the right word as the surface is broken by deep ravines; the road has to follow a winding route from one elevated section to another – perhaps the origin of the name, since the root meaning of jawl is to wander or ramble. The scene is like a mountain range in negative, its topography the result of attrition. Wind and rain first etch then gouge the surface, depressions become runnels then valleys then gorges. The few people who live here, in isolated stone houses, seem impervious to the horror vacui that haunts the place. We went on in silence. The sky blackened and came down to meet the horribly potholed road. At intervals, signposts with numbers pointed into the mist. And then, slowly at first but with increasing gradient, the road started to descend, dropping into the underworld of the Wadi.

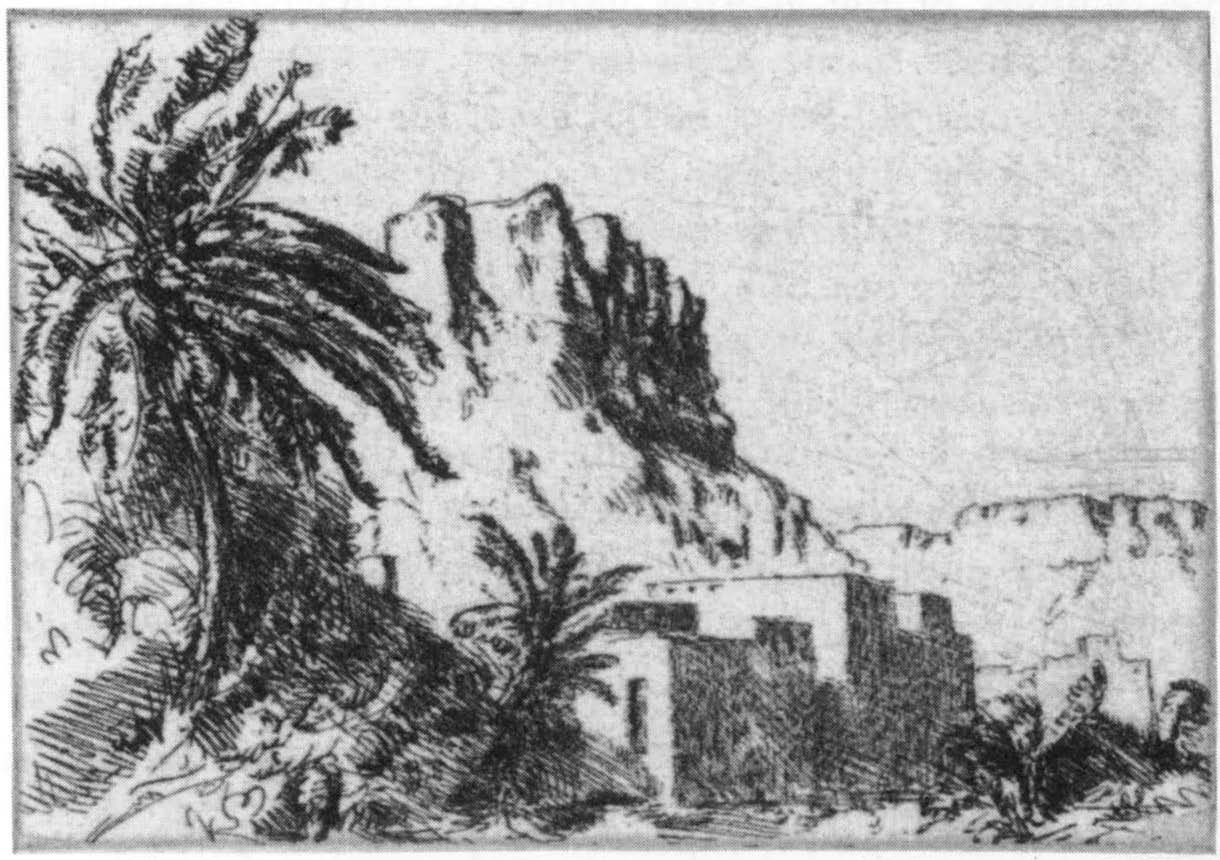

The first thing to catch the eye after hours on the naked uplands is the green, of palms, of alfalfa, of ilb trees. In the Wadi’s palette, houses are secondary and blend into the dun landscape from which they grow. The light was failing, and by the time we left the side-wadi of al-Ayn and emerged into the main valley, twilight had swallowed the long vistas of buttresses that confine it. The great city of Shibam was a crouching mass darker than the darkness around it.

This glimpse of Hadramawt before nightfall showed that, even if in some ways it is sleepy and insular, one activity continues with irrepressible vitality: building. Everywhere, there are unfinished top floors and herringbone stacks of mud bricks. Many of the older houses and turret-cornered little forts are crumbling – in the last stage of disintegration, the structures look like termite mounds. But new buildings rise all around. It is a cycle of dissolution and rebirth.

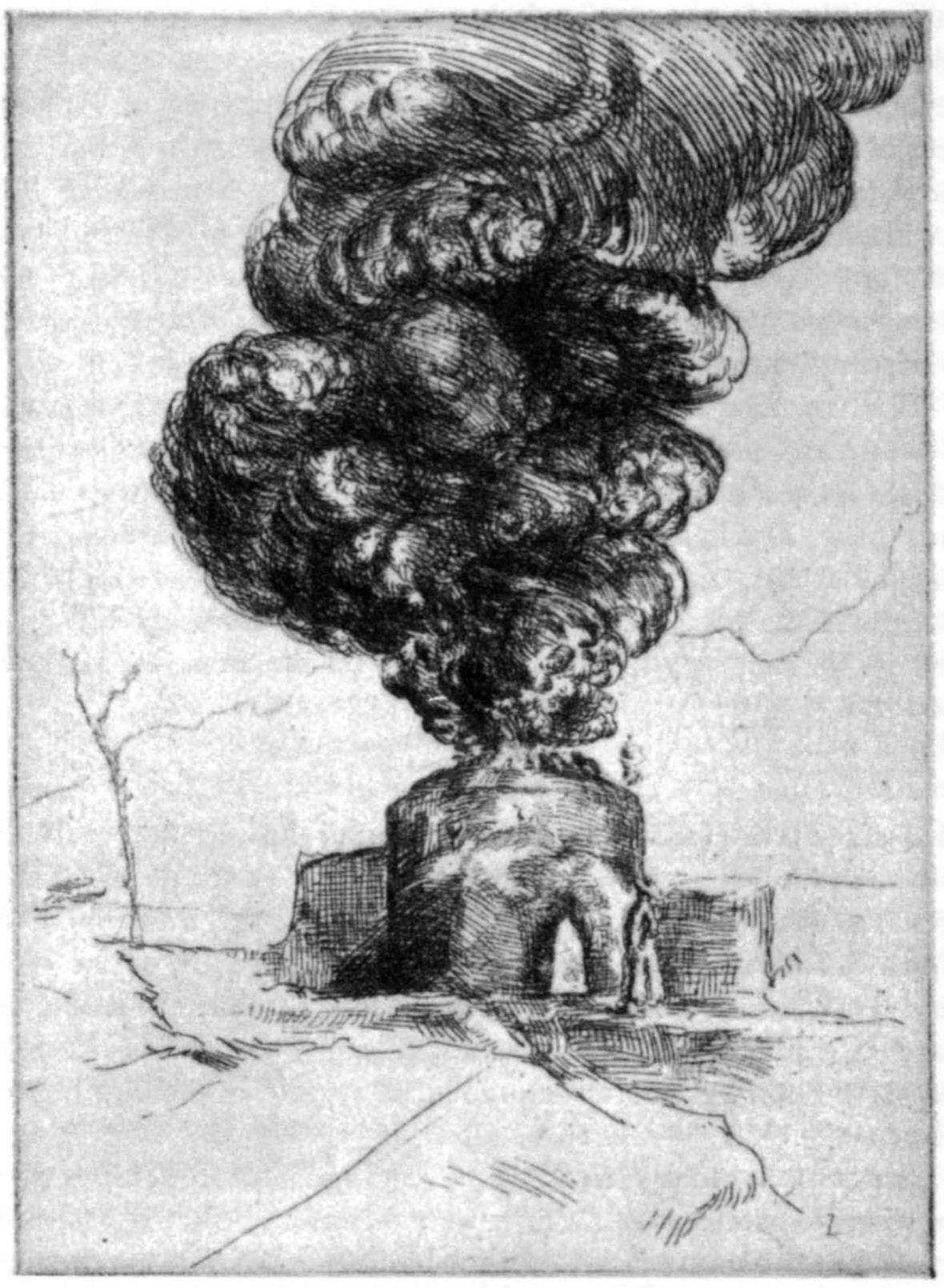

The cement block arrived a few years ago, and sometimes there are strange marriages of an ornamental cement porch with a mud house; but the mud brick is still the basic element and the one best suited to Hadramawt’s climate. The method of building is deceptively simple. Large flat bricks of mud and chopped straw, dried in the sun, are mortared and then plastered over with the same ingredients. Houses are given a waterproof icing of lime plaster, itself produced by a laborious process: throughout the Wadi you see little shelters where teams of men whack the stuff with long paddles for hours on end. Stone is hardly used, except in supporting columns built of flat stone cylinders like stacks of film canisters. There are no short cuts in Hadrami building; the more time that is put into its construction, the longer a house will last. An esoteric guarantee of permanence is to have a sheep slaughtered and its blood smeared on the corners of the building.

Inside, Hadrami houses are complex and enigmatic. The sparsely furnished rooms are almost an afterthought to the high, blank-walled corridors and staircases which seem to fill much of the building’s volume. Everything seems designed to bewilder, like a maze for laboratory rats, until you realize that the intention is to prevent the meeting of incompatibles – different sexes, different classes. An illusionist would love Hadrami houses, for in them people can be made to appear or disappear.

From the outside, these buildings are sober to an eye used to the baroque plaster frills of San’ani ornament. Façades are unadorned, decoration limited to the wood of shutters and doors. ‘“Architecture”’, Harold Ingrams wrote, ‘is the one word which describes the quality which makes Hadramawt different from any other country.’ It is an architecture where form, function and mass have won over ornament.

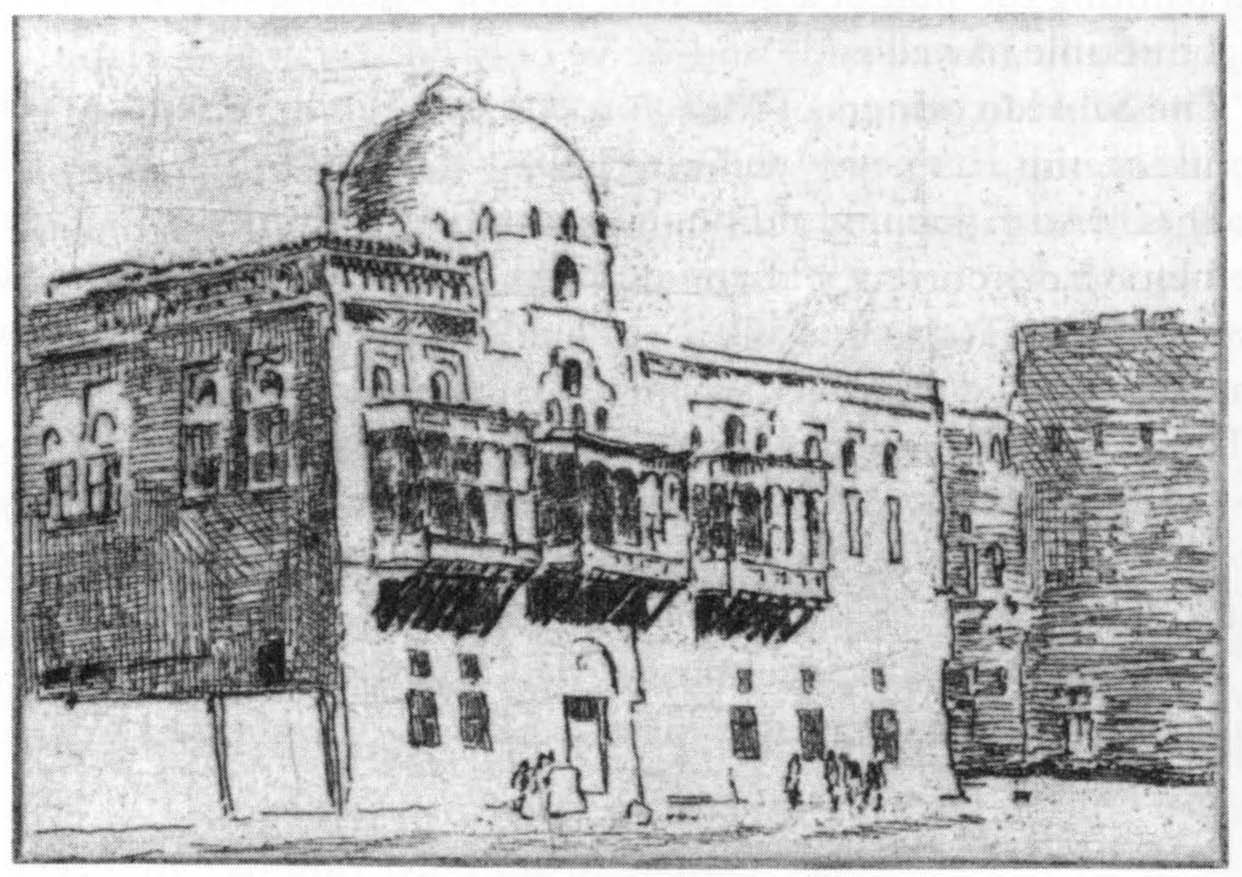

There are exceptions, like the playing-card symbols stencilled in pastel colours over the houses of Daw’an, and the tombs of holy men with their zigzags of green striplights; but it is in Tarim that the mask of sobriety really slips. Alberto Moravia saw San’a as a Venice where dust had replaced water; but then, he hadn’t been to Tarim. Here the palazzos of the merchant sayyids, founded earlier this century on the wealth of the Orient, are sinking into a lagoon of dust. Extraordinary hybrids of colonial, Classical, Mogul and Far Eastern elements, they are – amazingly – executed entirely in mud. Friezes and flutings are picked out in lapis lazuli, topaz and turquoise, and as the colours fade the structures behind them collapse. Only the mosque of al-Mihdar, its minaret rising like a stretched lighthouse from a sea of dusty palms, is pristine. The pleasure-domes of Tarim are too much for the UNESCO people with their arts and crafts faithfulness to materials, and their owners are too busy making money in Saudi Arabia. Unless someone steps in to champion them, the palaces of Tarim will succumb, though gracefully, it must be said.

Earlier this century, Western architectural taste found itself teetering, so to speak, on the cornice of a dilemma: one was told that clean lines, uncluttered volumes, multi-storey living, were good; at the same time, there was a suspicion that buildings constructed according to these criteria might somehow be inhuman, that modernism might turn out to be faddishness. What if Le Corbusier was a charlatan? An innate visual conservatism looked for precedents and found none. Then the pictures of Shibam came out and everyone sighed with relief: skyscrapers had a vernacular pedigree, and a long one. High-rise was OK. It was U to live in a cube.

Shibam, the Manhattan (or Chicago, or, now, almost any other major city in the world) of the Desert, is not in the desert but on a rise in the middle of the Wadi, surrounded by palm groves. Individually the houses are no more remarkable than many others across Yemen; but they stand together and can be framed in an instant by the eye and – more important – by the viewfinder. Shibam, with The Bridge at Shaharah and Dar al-Hajar in Wadi Dahr, has become the ultimate visual cliché of Yemen. It has even appeared in an advertisement for American Express.

Just as the houses of San’a descend from that splendid prototype of Ghumdan, those of Shibam originate in an ancient model best seen in the palace called Shuqur in Shabwah, built when Rome was still an insignificant town. The archaeologists estimate that the palace was around eight storeys high – the same as the tallest houses in Shibam.

Shibam and San’a have much in common. They became prominent at about the same time, both developed the idea of the tower-house, both are situated at central points on trade routes. Today the similarity ends there. San’a is lively, colourful, chaotic; Shibam is hushed. There is little movement in the principal public space, the square behind the main gate. Beyond this on the town’s narrow streets, an outsider feels like an intruder. Eyes watch your every movement – the eyes of goats peering down from first-floor windows, of chickens in hutches hung across the street to keep them safe from predators, other eyes behind lattices. A few children wander around, but otherwise there is little human activity. Innate Hadrami reserve is a factor; so is Marxist conditioning. More important is the depopulating effect of emigration – of those Yemenis who were able to stay on in the Gulf States after 1990, many were Hadramis, for they had been best able to blend in with their adopted countries. But I feared also, entering the city for the first time, that the hush of Shibam was also that of a museum.

On the far side of the flood course, on a bluff beneath the city’s water tank, an assembly was gathering as it does most afternoons at around five. Today they were mostly French, about twenty-five of them, and as the hour approached chatter diminished and was overtaken by a reverent and suspenseful silence. Marsupial pouches disgorged fittings and filters and macros, film packaging was secreted for later disposal. These were not the sort who dropped litter. Nor did the sun disappoint. For a full ten minutes Shibam turned to gold and the air was filled with Oohs and Aahs and the whirring of zooms.

It would be unfair to criticize Shibam for being photogenic; moreover, they were good tourists, closely shepherded and as unobtrusive as one can be in pistachio-coloured leisurewear. There wasn’t even a pair of shorts among them. But I wondered what they saw, what the German corporate bonding group who visited Yemen for three days to see Shibam saw, and suspected it was an artwork, an architectural Mona Lisa, supremely beautiful but ultimately incomprehensible, preserved by UNESCO yet lifeless, far removed from the world of coming-to-be and passing-away. I longed for a used-car lot, a cement factory, for the erosive effects of wind, rain, sewage and raw economics to disfigure the place. It was a matter of respect for the decency of decay. As the poet-king As’ad al-Kamil said:

Nothing can last while the fickle sun

Rises not from where it sets;

Rises limpid, red,

And sets saffron.

The churlish moment passed. Now, at 5.45 p.m., the sky to the west was streaked opalescent pink and cobalt in big vertical stripes. It was nauseating, it was magnifique, and I wished I had a camera too.

In Shibam, I had to deliver a letter to the uncle of a Hadrami living in San’a. Finding the house was not easy, but just when I thought I was irretrievably lost a child materialized and led me to it. I banged on the door and waited. A woman’s voice called from a high lattice: ‘There’s no one at home.’ I said I would give the letter to the child, but the door swung open by itself. The child led me up the staircase and into a room, then dematerialized. I sat there not knowing what to do, and was about to leave when I noticed a movement out of the corner of my eye: a tray with a samovar and a tea glass had appeared in the doorway. I poured myself some tea, drank it, put the letter on the tray, and left.

Next day, I managed to get a seat on the little plane from Say’un to al-Mukalla. The aircraft arced over the Wadi, climbing rapidly to hop over its thousand-foot southern escarpment. Suddenly that green and peopled world was far away, the jawl below like some grey northern sea. It was not difficult to see how Wadi Hadramawt had kept itself apart.

For me, the Hadrami interior remained – like the insides of its houses – aloof and enigmatic. I felt as though I had been wandering around a painting by de Chirico: a place drenched with light but empty of people.

Back on the edge of the ocean I felt a sense of relief. The Wadi walls were confining, more so even than Aden’s volcanic mountains. I wondered if all Hadramis were closet claustrophobes, and if this was what made them travel.

From medieval times onwards Hadramis colonized the East African coast. The exodus to what is now Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines began not much later, probably in the fifteenth century, and it was in the Far East that Hadrami acumen reaped huge profits. Even after the Japanese occupation, the al-Kaff family in Singapore were still worth around £25 million. Today, the world’s reputed richest man, the Sultan of Brunei, is part-Hadrami. Most expatriate Hadramis kept in close contact with their native land, sending their sons home to study and marry. The majority would eventually return for good, some to set up as small traders, the better-off to become gentlemen farmers.

On the Arab of the desert, Jan Morris has written, ‘the Bedouin was every Englishman’s idea of nature’s gentleman. He seemed almost a kind of Englishman himself, translated into another idiom.’ In fact the wealthy Hadrami, supervising his model palm groves, poring over manuscripts in his newly built mansion – paid for by money made overseas – was closer to the image of the eighteenth-century English nabob returned from the East. And, sequestered within fine houses, well-to-do Hadrami ladies lived a life of social intrigue, petty squabbles and boredom that Mrs Gaskell would have recognized. Parochialism and far-flung travel blended to produce something curiously familiar to Freya Stark and the Ingramses.

The effects of emigration were noted by von Wrede, who in 1846 stayed with a shaykh of Wadi Daw’an who had lived in India, spoke English, and had a copy of Scott’s Napoleon. Daw’an, at the western end of the main valley, contains some of the most prosperous houses in Hadramawt. Cliffs of buildings, some painted in harlequin colours like a Battenburg cake, are banked up the base of the canyon. Its wealth derives partly from overseas, but also from a local product – honey. Daw’ani honey is the most expensive in the world.

Entering Daw’an on a later visit to Hadramawt, I was stung on the chin. By the time I reached al-Hajarayn, perched on a cliff above the flood course, my face was swollen into a qat-chewer’s bulge. Down on a rise in the valley floor was a tent, not a badw house of hair but a heavy canvas thing from an army camp. It was surrounded by quadruped hives – earthenware cylinders raised on metal legs. They might, with a little imagination, have been rounded up and driven along the valley. This, in fact, is almost what does happen, since the beekeepers live a semi-nomadic life, travelling around the valley in search of the best pasture for their swarms.

I penetrated the buzzing cordon warily.

‘What’s wrong with your face?’ asked a man in the doorway of the tent.

‘I was stung.’

‘Stung? Where?’

‘Here, on the chin.’

‘I mean, were you stung here at al-Hajarayn?’

‘Oh, I see … No, back there down the road.’

‘That’s what I mean. My bees wouldn’t sting anyone. They’re the kindest bees in Daw’an. It must have been a foreign bee that stung you. There’s a lot of swarm-smuggling these days.’ Kind bees. Swarm-smuggling. And a curious wicker object by the tent door turned out to be a hornet-trap. The world of Daw’ani apiculture seemed bizarre.

Over lunch in the tent, the beeherds explained that the quality of their honey was the result of the bees’ pasturing only on ilb trees – Zizyphus spina-Christi. There was a lot of cheating, bumping up yields with sugar-water and mixing different grades, but my hosts would have nothing to do with this. Their baghiyyah grade was the finest available – the finest honey in the world. It smelt of butterscotch. It was the single malt, the unalloyed vintage. The price was commensurate: the equivalent of £40 for a good comb at the honey merchant’s in al-Mukalla, and far more by the time it reached the market in Saudi Arabia, where it is believed to firm up sagging sexual potency.* Here at source the prices were cheaper, but still I could only just afford a comb of the inferior winter grade. Even so, testing a fingerful – on the tactile level not unlike eating caviare, bursting through cells to a rich and melting interior – the honey was so strong and fragrant it was hard to imagine it was only the cheap stuff. The Classical geographers mention Arabia Felix as a source of excellent honey, and probably little has changed in production methods since their day, though the queen, or ‘father’ as she is called here, is now kept in a plastic hair-roller instead of the tiny wooden cage used formerly.

Al-Hajarayn, up above us on the cliff, is the site of Dammun. Here the sixth-century poet-prince Imru al-Qays was banished by his father for excessive drunkenness and fornication. Imru al-Qays’s tribe, Kindah, had emigrated long before, and their rise to power in northern Arabia had spun a web of jealousies that resulted in the killing of his father by a rival clan. When the news was brought to Dammun, the prince headed north to lay his father’s ghost.

Imru al-Qays the poet was already well known, and his lovesick lingerings at abandoned campsites were quoted all over Arabia. Pursuing the blood feud, he now became the most famous Hadrami traveller, a picaresque and melancholy figure, forced out of his secluded ancestral valley into the harsh world of Byzantine-Sasanian superpower politics. He became known as al-Malik al-Dillil, the Wandering King, and posthumously as Dhu al-Quruh, He of the Sores – in reference to his Nessus-like death, caused by a poisoned shirt presented to him by the Byzantine Emperor after he had flirted with an imperial princess. The Prophet, when asked who was the best of poets, said: ‘Imru al-Qays will lead the poets on their way to Hell.’ *

Imru al-Qays never succeeded in avenging his father’s death. Nor did he return to Dammun. Perhaps the fate of the Wandering King, deprived of honour, land and family, is a warning that binds the furthest-flung Hadrami to his place of origin.

I said goodbye to the beeherds and carried on along the pebbly track. A short asphalted pass lifts you on to the jawl, where the road surface ends as abruptly as it began. I stopped, walked to the edge of the canyon, and looked down. Daw’an was a sunken world, Lyonesse seen through crystal water. Up here, sounds were amplified by the valley sides: a child shouting ‘Shoot! Shoot!’, the thump of a ball being kicked, a donkey bursting its lungs in an ecstasy of sobbing brays, a dog snarling. A few paces back from the edge you could hear nothing, see nothing. Daw’an had disappeared.

It was a long way to the next stretch of tarmac on the al-Mukalla road. The light faded, more slowly on the uplands than in the wadi. Rock darkened from camel to tan to oak-gall like a sepia photograph in a bath of developer, leaving the motor track as the faintest scribble across the jawl.

Hours later, a light appeared on the horizon. It turned out to be a truck-stop. I squatted at the edge of the bare room and ate a tray of rice and a hunk of mindi, kid half roasted, half smoked over the embers of a lidded fire pit. In the corner of the room a video of American tag-team wrestling was playing; the few customers were too busy with their food to notice. Here too there was a reserve. People kept to their own personal space and the only sounds were the recorded grunts of blond giants trying to pulverize each other.

Three hours into my first qat chew in a Hadrami house, I was beginning to think the Hadramis really were a lugubrious lot. There had been none of the playful banter that begins a San’a chew. Salim, our host, who had been brought up in Kenya and was now a trader in Say’un, insisted on speaking a grandiloquent version of Arabic, mostly on the fecundation of date palms. His son, who was in his late teens, sat looking uncomfortable in the middle of the room and speaking only when spoken to.

Now should have been the Hour of Solomon, but I was feeling tetchy and liverish. Until Unification, qat had been banned in Hadramawt; the Hadramis still hadn’t got into the rhythm of it. A couple of neighbours turned up and talked politics. Salim did not take part in the conversation but sat glancing at his watch. I wondered if we were outstaying our welcome. Suddenly, he bounded up and disappeared. The sunset call to prayer sounded, the others left, and Salim re-entered the room – cheek empty – and began praying.

When he had finished he threw me some qat and started chewing again. After a polite pause I said, ‘Why don’t you carry on chewing and pray the sunset and evening prayers together?’ Immediately, I regretted the question. ‘Uh, that’s what they do in San’a …’

‘I am perfectly cognizant with the phenomenon. The people of San’a, of course, are notoriously lax in the performance of their obligations. “The best time to pray a prayer is when it is called,”’ he intoned sonorously. ‘To let what is no more than a pastime interfere with one’s duty as a Muslim is, frankly, inexcusable. I have even heard it said that there are some who pray without expelling the qat from their mouths, on the pretext that it does not necessarily affect the articulation. To me …’

The can of worms was open. I had to stop them wriggling out. ‘Perhaps I shouldn’t have mentioned it. After all, I’m not even a Muslim.’

‘You are not, indeed, a Muslim. But you are a complete San’ani.’

He was grinning. I laughed in relief. The ice, at last, had been broken. As we chatted, Salim’s Arabic became less ferociously inflected.

I was keen to find out what Salim knew about one of the geographical curiosities of Hadramawt – the Well of Barhut, a sulphurous and supposedly bottomless pit to the north of the Wadi. ‘Have you been to Barhut?’ I asked. ‘I read somewhere that it’s where the souls of the infidels end up.’

‘Yes, and they say there is a terrible smell of decomposition, and groans in the night. I haven’t been there myself. It’s a long way, far off the road that leads to the tomb of the Prophet Hud – peace upon him! But I can tell you the story of the well.’ He drew himself up.

‘When God created our Father Adam, He commanded the angels to prostrate themselves before him. At first they complained and said, “How can we do this, when he is made from clay and we from light?” But God said, “When Adam is expelled from the Garden, then I shall test him with trials and you shall have your recompense. Now do as I command!”

‘So the angels prostrated themselves before Adam – all except Iblis, who was to fall – and events took their turn until Adam was expelled from the Garden, and God began to test Man with trials, as you know. When the angels saw the afflictions Man was suffering, they said, “These are nothing. Any one of us could undergo the sufferings of Man and come out unscathed.” “Then,” said God, “let it be so. Choose the two strongest ones of your number. I will give them the form of men during the day, and at night they will revert to being angels.” So the angels chose two from their number, named Harut and Marut, and God did as He had said.

‘Harut and Marut, during their daylight hours as men, soon became respected by all humans on account of their wisdom, and people began to come to them to plead cases. One of those who sought their judgement was a woman named Zahra. She was a beautiful woman, and she fell in love with both Harut and Marut. Of course, being angels, they were exceedingly good-looking themselves. Zahra tried to soften the angels with words; naturally, they resisted her. Moreover, they were shocked to discover that she was married. When she suggested that they kill her husband, the angels were ready to give up being men and return to God’s presence for good. “But,” they said, “it is easy for us to resist the woman’s words and close our ears to the whisperings of Satan.”

‘One day, Zahra invited Harut and Marut to her house and brought them wine. “This is the easiest of Man’s trials to resist,” said the angels, “but let us try a little, so that we shall know what to avoid in future. Only a little.” Soon, though, they were drunk, and it took only a sign from Zahra for them to kill her husband and sleep with her.

‘When God saw this, He called the two angels into His presence and said, “You have sinned and have truly tasted Man’s afflictions. I give you a choice: earthly punishment, or that of the world to come.” Harut and Marut chose earthly punishment and God cast them into the Well of Barhut, named after a jinni of the Prophet Sulayman – peace upon him! – who had dug it. The well was full of snakes and scorpions, and there the two fallen angels are even now. Zahra, who had stolen from them the trick of flight, escaped to the heavens and was turned into a star. And there the story ends.’

I took my leave just before the evening prayer and walked out into the night. It was dead quiet. Rain had fallen, and the earth gave off a rich tobacco-like odour. The air was clear, and the stars were joining Venus, Zahra. I thought of the ending of Salim’s story. It all seemed to fit until the bit about Zahra. Why should the woman, this arch-temptress, have become a heavenly body?

Then I realized. The story must be ancient, dating back to the beginning of Islam when the old pagan cults still had a following. Here in Hadramawt, cut off from the rest of Yemen, Christianity, Judaism and the local monotheistic religion of al-Rahman had made few inroads into the ancient astral beliefs in which Venus was a prominent member of the pantheon. The Barhut story was both an attack on a pagan deity, recast as an evil seductress, and a didactic against alcohol, adultery and murder. But perhaps even stranger was that so uncanonical a tale should have been told by someone so apparently orthodox. It seemed to be another case of the Hadrami split personality.

I picked my way along narrow unlit streets, squelching through mud. Palms dripped behind high walls. Say’un is a garden city, rus in urbe to Tarim’s Venice of dust. In Say’un, I was staying with a Sudanese-American couple, he a Nubian from Dongola and she from the Mid West. Awad and Linda spent most of their time sifting through nineteenth-century land deeds in a turret of the Kathiri Sultan’s palace, a magnificent building like a Carème centrepiece. Its brilliant white plaster threatens snow-blindness. Their own house was a banqalah – a ‘bungalow’ – among the palms; despite the suggestion of colonial or English-suburban images, here the word means a guest-house. It was small but very grand, all blinding white lime-plaster like the Sultan’s palace; the upper floor was one large room surrounded by a loggia, the undersides of the arches picked out in the distinctive Hadrami eau-de-Nil. Downstairs was a tiny room in royal blue with a plunge pool, deliciously cold and swirling like a Jacuzzi when the pump was started to water the palm grove. The pool is exactly the same as those found in grand Georgian town-houses. One of the last Kathiri rulers was so smitten by the banqalah that he requisitioned it.

Linda had spent the afternoon, a Starkian one, with some nouveau-poor unmarried sharifahs (sayyid ladies) in Tarim. No sayyid husbands could be found for them, and marriage into the lower orders was unthinkable; so they spent their straitened spinsterhood in a complex of palaces joined by upper-floor bridges. They hardly ever left their houses.*

Just how frustrating strict endogamy can be is shown by the Hadrami reaction to news of the 1962 Revolution in San’a. While many Hadrami sayyids were unnerved, one observer reports that some spinsters of the al-Attas family in Huraydah greeted the expected collapse of the status quo with whoops of excitement: ‘We can get married now!’ In the event the old order has hardly changed, Marxist attempts to force marriages across social boundaries having met with implacable opposition, and the old proverb holds good: ‘The luck of a sharifah is blind. If she keeps chickens, the kites come and eat them. If she hangs out the washing, the sky clouds over. And if she loses her husband, she’ll never find another.’ The belief even used to be current that a non-sayyid who married a sharifah would be struck by leprosy.

We talked until late about the curious split personality of Hadramawt – parochialism and emigration, stagnation and progress, orthodoxy and heterodoxy – and decided that the polarities would never be reconciled. I went to bed and slept the sleep of the dead, as one does in Hadramawt (except in the Well of Barhut), not realizing until the morning that I was sharing my bed with a baby scorpion.

I set off early the next day to visit a prophet.

The night before, we had come up with a theory: it was precisely because the Hadramis had been conditioned to present a dour and monumental façade – like their houses – that they needed to let off steam occasionally – hence the festivities connected with Hud, the Prophet of God. Hud, who according to the genealogists was the great-grandson of Sam, is not merely a divinely sent messenger; he is also the father of Qahtan. I felt it only proper to pay my respects to the reputed progenitor of all the southern Arabs.

East of Tarim something changes. You cannot say it is the landscape, although the valley narrows slightly. The wadi’s name is different – al-Masilah, the Watercourse – but the same water flows in it. What is different is that civilization, in the sense of ancient urban culture, has been left behind. Down the great length of al-Masilah there are a few communities, at first quite sizeable, like Aynat, but in no way urban. For the rest of al-Masilah’s 150 miles there is nothing bigger than a hamlet. East of the point where the wadi meets the coast there are some more fair-sized settlements – Sayhut, Qishn, al-Ghaydah – but they are only overblown villages. Crossing the border into Omani territory, Salalah is a creation of the past two decades; before, it was a collection of small dwellings huddled round a fort. From Salalah all along the southern coast of Arabia there are no major settlements. Only when you turn the corner into the Gulf do you find places with any pretension to being urban; but even Muscat is tiny, a lapis-lazuli palace and a few other houses locked in the jaws of a bay between Portuguese forts, followed by a string of suburbs with no urban heart. Round the tortuous Musandam Peninsula and into the inner Gulf, all the emirates and shaykhdoms that cling to the shore are the recent and monstrous spawn of Western politicking and the Western thirst for oil. It is only at the head of the Gulf that, with al-Basrah and Baghdad, you come again to an ancient urban society. To fill the void, the Arabs built cities of the imagination, the cities of Ad and Thamud which were wiped off the earth for their corruption. Hud was the prophet who foresaw the destruction of Ad, and when urban Hadramis visit him they are reminded of what could happen to them. Leaving Tarim, they are venturing into the margins of an uncivilized world.

Some way past Tarim we turned off the road and headed for a small but dramatic outcrop like an island in the flood course. This was Hisn al-Urr, a castle of great antiquity probably constructed by Imru al-Qays’s people, Kindah. Such a site was no doubt in use long before, and long after; the massive walls are still intact. We clambered up and Jay, my travelling companion from San’a, posed in nearly immaculate memsahib white, parasol raised, on the summit of a bastion. The silence was overwhelming.

Suddenly the silence was broken, by a faint rhythm that turned into a clatter then a din. A helicopter came from the east, from nowhere. It circled once and was off up a side wadi that first amplified, then swallowed the noise. The silence ebbed back, stronger after its negation.

Unexpectedly, the road improved after al-Urr. Recent patching has made it one of the better ones in the Hadramawt interior, which wasn’t saying much. We had just missed the pilgrimage itself, but were benefiting from the annual maintenance of the track to Hud, paid for by the contributions of the pious.

Finally the tomb appeared under the southern escarpment, a gleaming ensemble of dome and prayer hall surrounded by a town. We dipped down across the watercourse, surprisingly deep, and stopped the car at the top of the far bank. Not only the tomb complex but the town itself were freshly plastered, the biscuit-coloured walls of houses finished off with brilliant waterproof nurah. And yet the place lacked the element which would have made it truly urban: people. It was empty, totally empty. The town is only inhabited for a few days around the pilgrimage, and wealthier Hadrami families maintain houses here for just this brief season. We had expected some delapidation, some evidence of the decline of the Hud ziyarah – the ‘visit’, or pilgrimage – during Marxist days, but there was none. It was as if a jinni had been commanded to build a city but had stopped short of populating it.

If at Hisn al-Urr the silence had been overwhelming, here it was unearthly. I realized that during our first stop there had in fact been sounds, a barely audible wild-track made by the wind and the little sandfalls caused by scuttling lizards. Since the appearance of the helicopter Jay and I had hardly spoken. Now, we tiptoed around. To make a sound would have been blasphemy. And yet, at our feet, was the evidence of mayhem, a litter of packaging from biscuits, cheese spread, fruit juice and, above all, from toys of a warlike and noisy nature: ‘Pump Action Shotgun with Dart – for ages 3 and up’, ‘Cap Gun Hero’, ‘Dynamic Cap Gun’, and ‘Mystery Action Wind-Up Helicopter’. Clearly the fairground aspect of the pilgrimage was still alive: Hud could still pull crowds.* I sat on a wall and wondered why.

Yemen is littered with the tombs of holy men and prophets, many of them visited at annual festivals. But none enjoys anything like the popularity of Hud; none is honoured by having an entire town built purely to accommodate pilgrims. The motives behind this extraordinary display of reverence had to be connected with Hud himself.

Hud and the Adites make several appearances in the Qur’an. The essence of the story is that the post-diluvian age of innocence had become increasingly flawed. The Adites, who were given wealth such as the world had never seen, refused to thank God for His blessings. Worse, they worshipped idols and tried to imitate Paradise by building fabulous cities like Iram of the Columns. The Prophet Hud warned them against such blasphemy, but was ignored. God therefore destroyed the Adites with a violent wind, a sandstorm of apocalyptic proportions.

A mass of legend has grown around the story. One sub-plot says that before the final catastrophe, the Adites were attacked by a plague of ants. The Adites were giants, and the ants were accordingly scaled up, ‘the size of dogs,’ one commentator says, ‘each one big enough to unseat a rider from his horse and tear him limb from limb.’ The cliffs of Hadramawt were built by the Adites as platforms on which they would sit to keep out of the insects’ reach. Hud himself was a giant, which accounts in popular belief for the long stone ‘tail’ extending up the slope behind his tomb. Different writers give different measurements for the tail’s length. Like the stone circles in Britain which are said to be uncountable, Hud seems to be immeasurable.*

Another local tradition says that after the destruction of Ad, Hud was chased by some of the remnants of the Adites and cornered at a dead end, the wadi wall under which I was sitting. (The camel races held at pilgrimage time may be a commemoration of the chase.) The moment his pursuers caught up with him, the ground opened and swallowed him and his camel – all but the camel’s hump. This was petrified into the huge trapezoidal boulder built into the roof of the prayer hall. Appropriately for a people so attached to their land, their ancestor had been ingested by it.

It was tempting to see the Qur’anic story of Ad’s destruction in a sandstorm as an account of the climatic change that altered Arabia between five and seven thousand years ago. It was tempting, too, to see the connection between Hud and the camel as a folk-memory of how the South Arabians were able to overcome the problem of transport in a harsh, dry climate.* And it was even more tempting to think of the Qahtanis as incomers: many of the early historians describe them as muta’arribah, ‘Arabianized’, while the Adites are the aboriginal arab. But if Hud, as the Qur’an states, was himself an Adite, how could his son have been an incomer?

Archaeology has confirmed the existence of many of the alleged descendants of Qahtan – Saba, Himyar, Kahlan, Hamdan and so on – at least as groups, if not as individuals. Genealogy – the arrangement of these names in relation to one another and to earlier peoples – tends to be treated with extreme scepticism by modern historians. But it should never be dismissed: as a contemporary Yemeni historian and archaeologist has said, ‘While it may not be the voice of history, it is the echo of that voice.’

Whatever their relationship to the present-day Yemenis, a prehistoric people existed. In the sands between Hadramawt and Marib, and further east into Omani territory, they left traces of their passing in the form of thousands of finely worked stone arrowheads. These can be picked up around the shallow depressions which were once waterholes, where hunter-gatherers would shoot the rich herds of game that disappeared with desertification. Until someone stumbles across one of those gem-studded cities, it is these arrowheads that are the true memorials of Ad.

My visit to Hud had begun as a personal pilgrimage. I was going to pay my respects to the ancestor – at least in a symbolic sense – of the people to whom I had grown so close. My own ancestors were lost in a welter of Celts, a muddle of Angles; Hud was, for me, almost an adoptive grandfather figure. But the more I considered the few tantalizing facts about him given by the Qur’an, and the body of fable with which the Yemenis had fleshed him out, the further Hud the father of Qahtan receded into the mists – no, the impenetrable fog – of time.

The sun, and the whiteness of the buildings, seemed more intense. Jay had wandered off to explore the ghost-town. In front of me was a sort of triumphal staircase, its two wings joining above the prayer hall then rising like the climactic approach to the piano nobile of a Palladian mansion. I climbed slowly. The only sound was the throb of blood in my inner ear, which beat faster as I neared the top of the staircase. Everything was saturated with light; blinded, I had to feel my way past the pillars that supported the dome.

At last, I was at the holiest spot in Yemen.

When my eyes adjusted to the shade, I saw that the tomb was empty. There was no grave; not even a cenotaph. Just a few gim-crack incense-burners and empty ‘Chef’ ghee tins on a shelf, and a cleft in the rock where, they say, the ground failed to close completely. The lips of the cleft were smooth and slightly damp.

A seventh-century visitor said: ‘And there we saw two rocks next to one another, with a space in between big enough for someone thin to squeeze through. So I squeezed through. And there I saw a man upon a couch, very brown, with a long face and a thick beard. He had dried out on his couch. I felt part of his body and found it to be firm and uncorrupted. At his head I saw an inscription in Arabic: “I am Hud who believed in God. I sorrowed for the impiety of Ad and their refusal of God’s command.” ’

I had come in search of a corporeal Hud. It was a long way to his resting place here in the margins of Yemen, but the last stage, via the crack in the rock, was the longest. Hud the Prophet is there in the Qur’an. Hud the Progenitor, the grandfather of Yemen, is harder to reach; squeezing through to him would need a lot of faith.

The idea of a single ancestor is almost certainly a simplification; but if by personifying their origins in Hud and Qahtan the Yemenis have rationalized their own history, they have done no more than most other peoples. And while the roots of the family tree may be more complex, they are – for the moment – as deeply hidden as Hud.

East of Hud along al-Masilah there is another change, this time in the place names. The list of settlements, as given by Ingrams, runs: Qoz Adubi, Taburkum, Marakhai, Bat-ha, Dhahoma, Buzun, Semarma. Still physically in Arabia, you have fallen off the Arabic map, a map on which the toponyms are comfortingly familiar as far away as the north of Syria or the Atlantic coast of Morocco. It is like driving out of Newtown in the Welsh borders and suddenly seeing a sign for Llanwyddelan. A parallel with Welsh, or Gaelic, or Provençal, is not far-fetched. Here is a remnant of the days before what we know as Arabic took over Southern Arabia, still a Semitic language but one more closely related to that of the ancient epigraphic texts, pushed into a backwater of the peninsula. It is not that the Mahris who live here are a race distinct from other Yemenis; rather, being so isolated from contact with the North Arabian world where Arabic came from, they have held on to the old speech by a quirk of geography.

The Mahris also preserved until recently some characteristics of ancient South Arabian social organization, like the alternative matrilineal descent system. In this, for example, a child born out of wedlock was brought up by his maternal uncle: no stigma attached to him, and he enjoyed full rights in his mother’s clan. Other customs throw light on practices criticized by early Islam. Until recently, for instance, the women of Mahri Dhofar used to knot pieces of twine while heaping anathemas on the tribe’s enemies – an illustration of what the Qur’an refers to as ‘the women who blow upon knots’.*

In the whole vast expanse of more or less empty country where Hadramawt Governorate ends and al-Mahrah begins, al-Masilah is the prominent topographical feature. It is that rare thing in the Arabian Peninsula, a real river with hidden fishy pools, overhung with trees. The desiccated right angles of Wadi Hadramawt have been replaced by a softer landscape where you can lie on grass – grass! – and dangle your toes in a burbling stream that smells faintly musty, like last Christmas’s brazil nuts.

Down near the seaward end of al-Masilah, on featureless heights above a bend in the river, is the grave of another giant, Mawla al-Ayn. Unlike Hud, al-Ayn does not appear in the Islamic canon.

We bumped up a rough track and climbed out of the pick-up. The tomb was a barrow about eighteen feet long, and the ground around it was scattered with objects – a pierced lead seal, an ancient .303 cartridge case, a little package of sewn cloth – all half-embedded in the dust. The barrow itself was adorned with a few very rusted tin cans and an old hinge. My companions stood next to one another at the foot of the grave and recited the Fatihah – the opening chapter of the Qur’an – as one does when visiting the departed. Then they bent down, scrabbled up some dust from between the rocks of the tomb, and rubbed it into their hair and headscarves. One of them gave me some dust and told me to do the same. ‘Barakah,’ he said, ‘a blessing.’

Later, in a teahouse in Sayhut, I asked a venerable-looking man, the sort who would know about such things, about Mawla al-Ayn. He could not add anything to what I had already been told, but suggested that I visit Ba Abduh of Qishn, the local authority on walis. ‘And on the way you could visit Asma al-Gharibah – she is a waliyyah, a holy woman. They say she was out at sea in a boat when she suddenly felt she was going to die. She told the crew and instructed them to throw her body into the waves. The men were shocked – she was a great waliyyah and should be given an honourable burial. But Asma said, “Do not be afraid. My body will find its own grave.” And it was as she said. Her body found its way to Itab, between here and Qishn. People still visit the spot by boat, and they leave coffee, sugar, flour and ghee there in case travellers pass by who are hungry or lost. And the strange thing is that by her grave a well of sweet water rises from the sea, from out of the salt.’

There was no time to visit Ba Abduh of Qishn, but I began to think about the story of the waliyyah and her miraculous well. The name of al-Ayn, the holy giant of al-Masilah, can mean ‘a spring of sweet water’. Further west, between Wadi Hadramawt and the sea, is the tomb of another holy man, Mawla Matar; Matar is an ancient personal name, but it is also ‘rain’. Then, in the Hadrami interior, is a fourth ancient grave, of the Prophet Sadif. Ingrams was told that he was another prophet of Ad, but he makes no appearance in the standard Islamic literature. There is still a tribe of the same name in Hadramawt, but the name of Sadif, the eponymous holy man, is yet another connection with water: sdf (the vowelling is uncertain) is the ancient technical term for a sluice gate controlling irrigation.

The four ancient holy people all share a link with water. The Islamic association of water with divine mercy is strong. Here, though, is a group of saints, clearly revered from ancient times, who seem in themselves to embody what, in a generally poor and parched land, is this most vital aspect of divine bounty.

Johnstone has pointed to a belief among the Mahrah and related groups in earth-spirits, a belief that their Arabic-speaking neighbours do not share, or have lost. It may be that in al-Ayn, Matar, Sadif and Asma al-Gharibah there is a faint and only sketchily Islamized memory of a chthonic cult connected with irrigation, a cult which goes back far beyond monotheism, beyond even the celestial religions of Hadramawt and Saba – to the very dawn of tillage, when the desert had smothered much of Arabia, the last hippopotamus was dust, and the Qahtani family tree was still struggling to take root.

Back in Say’un after the visit to Hud, I noticed a pungent and disagreeable smell. Awad saw me wrinkling my nose. ‘It’s this carpet. We found it in the old animal shed and … well, you can guess the state it was in. So I washed it and it got worse.’

I went and looked at the carpet, a magnificent Tabriz rug that had probably come via the Mecca pilgrimage. It was good enough to date to the time the Sultan requisitioned the house, but it was ripe with the stink of mildew and other odours.

Next day, equipped with brushes and half a dozen packets of soap powder, we set off for Tarim and the irrigation tank outside Qasr al-Qubbah, the Palace of the Dome, the ‘perfect Riviera villa’ where Ingrams stayed in the 1930s. Now it is a hotel, a little over-enthusiastically painted but, unlike most of the Tarim palaces, still in one piece.

I scrubbed away, up to my neck in grey and soapy water. Awad sat on the cement lip of the pool, giving the rug an occasional brush and frowning in concentration so that the lines on his brow echoed those on his cheeks – the deep parallel scars that identify a Nubian’s tribal origin. He was so much at home in Hadramawt that I was convinced he had Hadrami blood. It was not a farfetched idea, since among the conquering armies of Islam there were many Hadramis, and some of them had penetrated as far as Awad’s town of Dongola. But then, Awad is said to look at home in Texas, wearing cowboy boots and a stetson. So much for genealogy.

When the carpet was as clean as it would get, we hung it on an overflow pipe where it glistened in the sunlight filtering through the palms. I joined Awad on the edge of the pool and sat drying off. With the light and shade, and the pink and yellow cupola of Qasr al-Qubbah emerging from a sea of green with the tawny cliffs behind, it was like sitting in a Persian miniature.

The reverie was shattered by a high-pitched buzzing from along the track. It got louder until the source of the sound appeared: two very suntanned Westerners in shorts, riding four-wheeled motor cycles. They slewed round the corner, stopped in a cloud of dust, and dismounted next to us. The first one, who had a grey beard and a body like a grizzly, grunted a ‘Hi’; then, as his eye caught Awad’s tribal scars, a look of childlike wonderment came over his features. ‘Hey, what’s wrong with your face? You … you been in a fight with a tiger or something?’

Awad patiently explained the history and significance of tribal markings. The two quad riders listened with raised eyebrows. Outside the exchange, I considered the elements of the scene: a nearly naked and very white Brit; a ritually cicatrized Nubian who sounded like a Texan; two Texans working for a drilling contractor up on the jawl; a lemon and lime and raspberry mud palace. There was no question that the Americans were the most exotic.

Later, waiting for the Aden plane at al-Mukalla Airport, I was able to observe Homo petrolensis in his natural environment. The airport used to be deserted. Now, daily, it echoed with the voices of half a dozen nationalities, Egyptian, Palestinian, Lebanese, French, British, American. But it didn’t really matter where they came from. They all had the same steak-fed physiques, ballgame voices and expensive wrist accoutrements. Whatever the nationality, oil smooths over national differences and lubricates communication.

These two, though, had been temporarily displaced. I tried to picture where they had just come from. Somewhere, I suppose, up on the jawl where signposts with numbers point into the mist.

The pipeline which carries oil from the Hadramawt fields to the coast, opened in September 1993, arrives at the sea east of Shuhayr. Here, men in boiler suits and hard hats do unfathomable jobs on a desolate bluff, surrounded by a high fence and permanently blazing arc lights. It all looks like one of those evil-empire training camps that get blown up at the end of James Bond films. Most of its inmates are unaware of their place in the continuum of South Arabian trading history of which al-Shihr, a short distance further east, is a reminder.

The once-great city exported, according to a Chinese visitor of the twelfth century, frankincense, ambergris, pearls, opaque glass, rhino horn, ivory, coral, putchuk, myrrh, dragon’s blood, asafoetida, liquid storax, galls and rosewater. Al-Shihr, however, having like Aden ‘a great trade … with the Moors of Malabar and Cambaya’, caught the eye of the early sixteenth-century Portuguese, who raided it several times. At a spot by the shore, the tombs of the Seven Martyrs killed by the Franks in 1522 are still to be seen. They were resurrected in recent years, to become the first entries in the PDRY anti-imperialist role of honour. Ninety years on a Dutchman, van der Broeke, followed the Portuguese. His intentions were more peaceful, and he set up a trade mission and left behind three of his colleagues to learn Arabic by what would now be called the total immersion method. He did not call again until three years later.

But al-Shihr’s fortunes declined. Not long afterwards a Venetian described it, with Johnsonian disdain, as ‘a desert place where both Men and Cattle are forced to live on Fish’. It was overtaken as the main port of Hadramawt by al-Mukalla, although there are still a few memories of its greatness. You enter the town past a whitewashed gateway flanked by little cannon; bereft of its walls, the gate stands shut on a traffic island, a miniature Arc de Triomphe. Inside the town, carved doors and crumbling plaster speak of links with Goa, Lamu and Zanzibar, while a figure of astonishing sculptural ineptitude – it could represent Hiawatha or Hereward the Wake – rises above a fishy miasma to commemorate, presumably, more recent events.

Down on the beach the remains of another part of Arabian maritime tradition can be seen in a few small abandoned craft, the last of the sewn boats. Coir was brought from the Maldives – ruled in the Middle Ages by Yemenis – to bind together the vessels’ planks with enormous cross-stitches. Sewn boats are mentioned in Classical sources, and later writers attempted to explain the reasons behind this method of construction: the medieval scholar al-Mas’udi said that, unlike the Sea of al-Rum (the Mediterranean), the Ethiopian Sea (the Indian Ocean) dissolves nails; the traveller Ibn Battutah thought that sewn vessels withstood collisions better than nailed ones; while the late fifteenth-century Rhinelander Arnold von Harff believed that the Arabian Sea contained magnetic rocks which would suck all iron out of a boat’s timbers. Now, in al-Shihr, the beached hulls are dumps for hundreds of rotting fish heads.

Of all the travellers’ tales emanating from Yemen, one of the strangest collections comes under the entry for al-Shihr in Yaqut’s great geographical encyclopaedia. It concerns the nisnas, whom we have already encountered as a race of men whose faces grow out of their chests, brought to Yemen by the Himyari ruler He of the Frights. Yaqut’s nisnas are different: they have only one of each member – one ear, one eye, one arm, one leg, and so on – and pogo at tremendous speed around the al-Shihr hinterland. One story tells of their stupidity.

Some people of the area went out hunting nisnas and captured one – on the hop, so to speak. They roasted and ate him under a tree where two of his companions were hiding. When one of these said to the other, ‘Look! They’re eating him!’, the hunters heard the voice and netted him as well. ‘You should have kept your mouth shut!’ they laughed, at which the third nisnas blurted out, ‘Well, I haven’t said anything …’ They caught him and butchered him too. Another tale reveals that the nisnas, although stupid, are accomplished versifiers. Some Shihris were joined on a hunt by an outsider, and when they caught a nisnas the victim extemporized a lament for himself:

Perforce, oft have I fled from evil men

In times long past when I was strong of limb.

But now my youthful days are gone,

And I am old and weak and thin.

The visitor was shocked that his hosts intended to eat the nisnas. ‘Surely’, he said, ‘it is forbidden to eat creatures that can recite poetry.’ ‘On the contrary,’ the Shihris answered, ‘it lives by grazing and has the digestive tract of a ruminant, so it is perfectly halal.’* Yaqut adds an apologia: ‘I admit that these stories are extraordinary, but I have merely quoted them from the books of learned men. If the information is at fault then I personally am not responsible.’ One can only echo the disclaimer.

Al-Shihr has always been associated with one of the strangest, and costliest, of all the sea’s products: ambergris. Despite its origin in the bowels of the sperm whale, it became part of the poet’s stock-in-trade of amatory metaphors: ‘and if you, my beloved, are perfume,/ You are ambergris of al-Shihr’. As well as being a constituent of cosmetics, in other more hedonistic lands it is mixed with tobacco for a voluptuous smoke. Ambergris also has a place in the traditional Arab pharmacopoeia: I have taken a course of ‘beef ambergris’, a concoction of the stuff with honey and herbs, in an attempt to improve my puny-looking physique. There were no visible results. Aphrodisiac properties are also claimed for it. I once bought a lump on the street in San’a as a wedding present for a friend. It smelt of the real thing, somewhere between truffles and BO, but turned out to be mostly candlewax.

Ambergris has always been a great rarity. Ibn al-Mujawir, who calls it ‘sea hashish’, ascribes its scarcity to ‘the wickedness of our opinions and the ugliness of our deeds’. Today, a fist-sized lump is worth at least the equivalent of £100. Down on the shore at al-Shihr, I decided to do some beachcombing. The problem was that I didn’t know what to look for. I walked over to an old man, who was painting the hull of a boat with an evil-smelling substance. He might be able to help.

‘Ambar?’ He grinned. ‘When you find it, it smells of shit. It even looks like shit. It’s only when it begins to dry out that the smell changes. And if you do find some, you must cut your finger and let the blood drip on to it. Then you must pray two prostrations and give a third of it away as alms. Finding ambar, you see, should be what they call “a discovery where joy is mixed with pain.” ’

I scanned the beach, which seemed an allegory for the ugliness of men’s deeds: it was used as a rubbish-tip and public lavatory. ‘So how do you tell the difference, I mean between ambar and shit?’

The man looked at the ocean. ‘Ah …’, he said, and smiled. I thanked him for his advice and left.

The coast of Yemen – all 1,200-odd miles of it excluding the kinks – is, for me, a tacked-on sort of place. The essence of Yemen is here diluted in the ebb and flood of outsiders. If I treat the coast as an afterthought, I admit to prejudice. It is the view from the tower-house in the mountains where I live.

With few exceptions, the coast is visually unexciting. But for this reason, other sense-impressions are heightened, and none more so than those created by smell. For someone used to dry mountain air, the increased humidity acts as a fixative for smells; at times they seem almost solid, trapped in a matrix of moisture. The Greek geographer Agatharchides, writing of the Yemeni coast, notes ‘an indescribably heavenly exhalation which excites the senses, even for those out at sea; and in the spring, whenever a breeze blows off the land, it comes redolent with the scent of myrrh and other trees’. As a sensual idée fixe it is remarkably persistent, occurring in the Bible, in the Latin poets, and in Milton:

When to them who sail

Beyond the Cape of Hope, and now are past

Mozambic, off at sea north-east winds blow

Sabaean odours from the spicy shore

Of Araby the Blest, with such delay

Well pleased they slack their course.

It was only when a new generation of Western romantics began to extol the antiseptic and odourless virtues of the desert that the cliché turned stale. Jeddah, T.E. Lawrence wrote, ‘held a moisture and sense of great age and exhaustion such as seemed to belong to no other place … a feeling of long use, of the exhalations of many people, of continued bath-heat and sweat’. He has a point: the Red Sea is an armpit of a place, where the perspiring proximity of Arabia and Africa generates heat, passion, magic. Hence the practice of infibulation, supposed to reduce the feminine libido; hence the zar, the exorcism by wild dancing and drumming of a jealous spirit, implanted by a rebuffed woman in the object of her desire by making him smell basil.

One could compile an olfactory gazetteer of the Yemeni coast, in the tradition of the founder of Zabid. He was said to have travelled down Tihamah, sniffing handfuls of earth as he went, until he came to a spot where he found ‘the butter, zubdah, of the land’; zubdah gave the city its name. Similarly, Awad ibn Ahmad ibn Urwah, a blind pilot of al-Shihr, was famous for his ability to tell a vessel’s position by smelling the mud on the ship’s plumbline. Once, while his ship was in the Gulf, the crew tried to catch him out by giving him mud from al-Hami, a few miles east of al-Shihr. ‘All this time,’ Awad said, ‘and we’ve only got as far as al-Hami?’

The Sabaean odours of Milton and Agatharchides are now faint. Frankincense has never recovered from the blow dealt it by the early Christian Fathers although, in a sense, it still contributes to Yemen’s hard-currency earnings in the form of tourism: roads (the Incense Road, the Silk Road, the Road to Samarkand) are marketable. And no more striking a setting could be desired for the Incense Road’s southern coastal terminus, Bir Ali, the ancient Qana. Here, at the end of a long sickle bay of white sand, is the sheer black bulk of an extinct volcano. On top are a few fragments of wall; below, the basalt outlines of port buildings where, occasionally, you can pick up a lump of frankincense that was intended for the nostrils of Capitoline Jupiter or many-bosomed Diana of the Ephesians.

Even if the shores of Yemen are no longer as spicy as they were, Tihamah at least is still redolent with the scent of full, a kind of jasmine, and of kadhdhi, Pandanus odoratissimus, a long spiky flower used to scent clothes. It is said only to bloom when lightning strikes its buds. Full, kadhdhi, civet, musk, ambergris and numerous other ingredients are combined to make the perfumes used today by Yemeni women.* The reason for their fondness for scent is in part a practical one, Ibn al-Mujawir says: the women of Yemen are ‘pretty of face, fond of chattering and loose of trouser-band’, which proves that their sexual appetite far outweighs that of men; consequently women have to ‘resort to using much scent in order to excite lust …’

And then there are the odours that accompany change and decay. The once-great coral-stone merchants’ houses of al-Luhayyah, where Niebuhr landed and played violin duets with the artist Baurenfeind to a people ‘curious, intelligent and polished in their manners’, fill with the reek of bats, then, giving up the ghost, collapse into dust, verandas, painted ceilings and all. Dust is everywhere. The cruel afternoon wind whips it up, turning the sun into a liver-spotted ball of yellow bile, then blotting it out. Caught in this recurring apocalypse, this death of air, there is nothing to do but assume a foetal position and wait for the redistribution of defunct earth, houses, creatures, to come to an end. Yet, by the grace of God, the sky opens most years and the coast gives off that most magical scent of all: rain on dust. It is the smell of life in death, and for a time the dunes sway with millet as far as the eye can see.

I have left out much material on the coasts of Yemen (much of it dashed, as Niebuhr said of Arab tales, with a little of the marvellous: a recent Sultan of al-Mukalla who would catch his serving-girls as they flew off a water-chute by the dozen; his neighbour of Balhaf who would throw enemies into the sea in perforated tea-chests – the more hated the enemy, the smaller the holes; a tribe descended from a mermaid; another whose young men rugby-tackle gazelles and play leap-frog with camels; two villages whose people, about their usual business one day in the year 1169, rose into the air, never to be seen again; Sufi adepts who stab themselves and hang by the neck from buttered poles; brides who train their pubic hair in plaits which their husbands rip out on the wedding night; a woman who spent her life standing on her head and was cured by a meteor shower; and so on). But then, I am not Scheherazade.