‘Stories of old …

Of dire chimeras and enchanted isles,

And rifted rocks whose entrance leads to hell,

For such there be, but unbelief is blind.’

Milton, Comus

THIS WAS TO HAVE BEEN a footnote on a place I would never see, but it grew, inexorably, into a chapter. Mine has been a digressive account; the Island of Suqutra, with the clarity of its light, the grotesqueries of its landscape, with its almost palpable genius loci – the spirit of old South Arabia now fading away on the mainland – is the last great sidetrack. To end there is, in a sense, to end at the beginning.

Suqutra had always been unattainable. Waq Waq, the Arab Ultima Thule at the far end of Mozambique, and sometimes beyond China, seemed hardly more distant. There it was on the map, somewhat larger than Skye, butted off the Horn of Africa, nearer to Somalia than to Yemen. But to get there … It might as well have been a place in a dream.

The origin of the island’s name is in itself obscure. Arab writers have glossed it as suq qatr, the Emporium of Resin, but it probably derives from the Sanskrit dvipa sakhadara, the Island of Bliss. This in turn may be a version of Dh Skrd, which appears in South Arabian inscriptions and seems to have given the Greek geographers their home-grown sounding name for the island, Dioskurida. The etymological enigma is compounded by questions about the racial origins of the Suqutris, whose veins are thought to flow with South Arabian, Greek and Indian blood, with perhaps a dash of Portuguese.

Medieval writers did their best to shroud the island in a mist of dubious or downright incredible facts. Ibn al-Mujawir says that for six months of the year the Suqutris were forced to play host to pirates, who would make free with the Suqutri girls. The pirates seem to have worked en famille: ‘They are a mean bunch, and their old women are meaner than their men.’ For defensive reasons, the islanders took to sorcery, and when the late twelfth-century Ayyubids sailed for Suqutra with five warships the Suqutris magicked their island out of sight. For five days and nights the Ayyubid fleet quartered the seas, but found no trace of it. A century later, Marco Polo reported that the Suqutris were the best enchanters in the world and could, Aeolus-like, summon winds at will. The archbishop in Baghdad, to whom they were subject, disapproved strongly. Moreover, the Venetian goes on, the islanders ‘know many other extraordinary sorceries, but I do not wish to speak of them …’

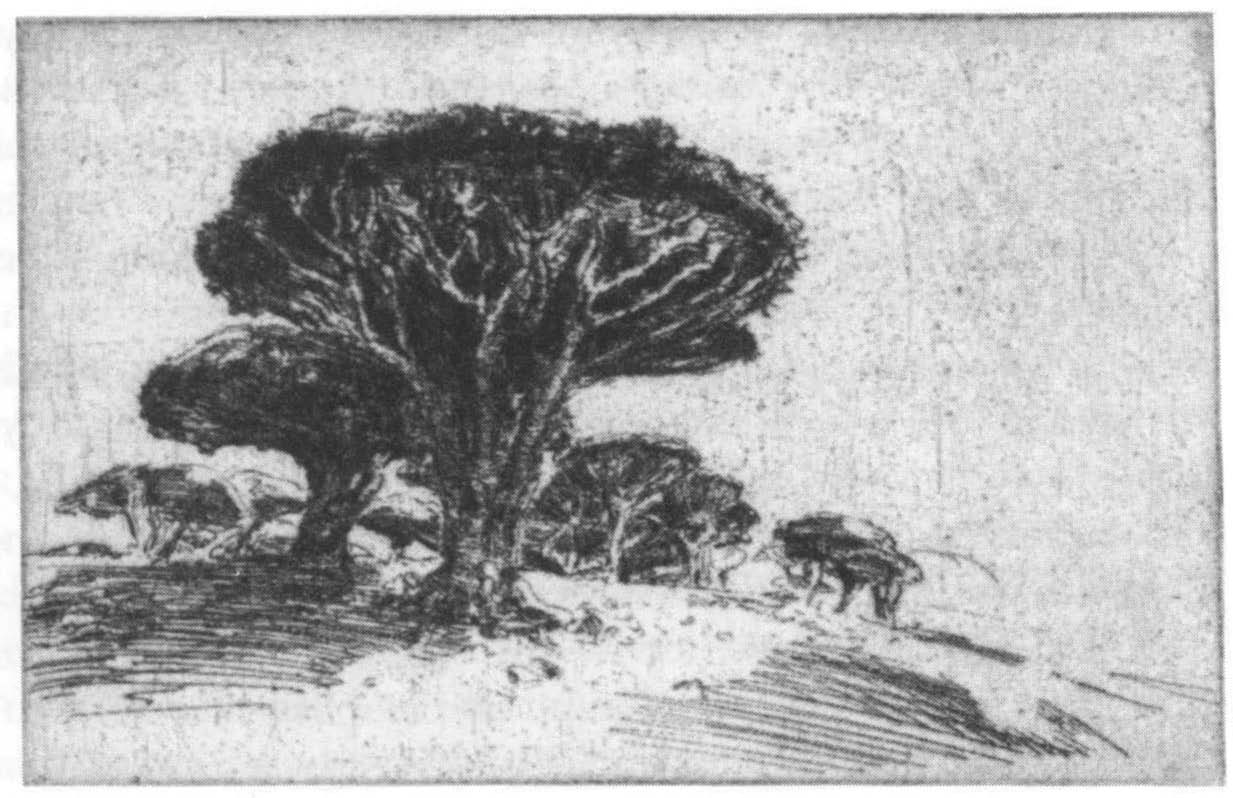

Eight centuries on, Suqutra occupies an apparently stable position 12½ degrees north of the Equator. It is home to a breed of dwarf cattle, to wild goats and donkeys, and to civet cats, which lurk in an eccentric arboretum where a third of the flora is unique to the island. The only pictures I had seen were of trees like yuccas and other pot plants but bizarrely mutated and enlarged; a few illustrating a British colonial official’s visit to the Sultan in 1961; and Wellsted’s drawing, done in the 1830s, of a scene near the capital Hadibu, which owed more to the Picturesque than to observation – a vista of craggy peaks with a foreground of artfully positioned swains, in which the artist himself surveys the view in a peaked cap, like a commissionaire lost in a willow-pattern plate. As for the written sources, my scant knowledge of the place was founded on rumour and travellers’ tales. There were whispers of witch trials as late as the 1960s; Cold War demonologists of the 1980s suspected the existence of a ‘massive’ Soviet naval base with nuclear submarine pens. Cartographers should, by nature, be more down to earth; but a look at the toponyms they had collected included Buz and Berk, Gobhill and Yobhill … Dinkidonkin.

Clearly the only way of proving the place actually existed, was not some elaborate fiction, would be to go there. But how?

For half the year, Suqutra is cut off from the rest of the world by violent storms; for the other half, a small plane is supposed to go there twice a week but flights are often cancelled or booked out. The islanders number around 40,000, but I had never met a Suqutri and knew no one who had. San’anis, if they had heard of the place, thought of it as the very margin of the world. (The problems of getting there are not new. Many years ago, it is said, a mainland woman whose husband had been on Suqutra for seven years could only get to the island on the back of a phoenix. The bird was meant to touch down on the al-Mahrah coast during the first ten days of the lunar month Muharram.)

And then, unexpectedly, the door to Suqutra opened. I was on my way to see Linda and Awad, waiting in Crater for the Aden-al-Mukalla taxi to fill up. It was two passengers short, and had been for most of the morning. Everyone was ratty, with lunchtime approaching and an eleven-hour journey ahead. Hadramis with plastic briefcases and new starchy futahs, worn ankle-length with the labels still attached, were trying to get each other to shell out for the empty seats. I had refused to part with a shilin more. If anyone was pressed for time then let him pay up. I was in no hurry. And since no Hadrami will countenance publicly spending more than the next one, we waited.

Another debate began, on whether to have lunch here or on the road. The driver knew that no more passengers would arrive in the dead small hours between the noon and asr prayers, and lay down to sleep on the desk of the Controller of Taxis, who had nothing to control. The Hadramis went off for lunch. Two passengers appeared. In an instant the driver was out of a deep slumber and running after the lunch party, and soon afterwards we were bowling north-east along the Abyan shore.

My fellow passengers were silent until we had eaten in Zinjibar. Conversations started, I unwrapped my qat. Then I heard something that made me sit up: it cut through the low hum of talk, audible as a stage-whisper. It was that phonemic phantom of South Arabia, the lateral sibillant which is a sh hissed through the corners of the mouth. I turned to the latecomers. ‘You must be Mahris.’

‘No, we’re from Suqutra – if you’ve heard of it.’

I must have stared at them longer than was polite. One of them said something incomprehensible and they both laughed. Still, they did look different. For a start, they were darker and much wirier than the Hadramis; then, there was something about the eyes, a slight upward flare to the outer corners, something feline. The best enchanters in the world.

They brushed off my apologies and we started chatting. Sa’d and Muhammad had finished secondary school in Aden. They were going home to be teachers. ‘And you’re flying from al-Mukalla?’ I asked them.

‘We wanted to, but the plane’s full and will be for weeks. You see, it’s the end of al-kaws, the season of storms, and everyone’s going home. We’re travelling by sea.’

I cut short my Hadramawt visit and returned to San’a. Less than a month after the meeting with Sa’d and Muhammad, I bade an emotional farewell to my San’ani friends. For them, the great and wide sea teems with leviathans and other terrors. ‘You’ll end up’, they said, and in all seriousness, ‘in the belly of a whale. And you’re a nasrani, so praying won’t do you any good.’ At their insistence I had written my will. With me was Kevin, recently returned from four years in Kuala Lumpur, Georgetown and Chiang Mai. In the Far East he had suffered from breakbone fever and from not being in Yemen.

We left a San’a strangely transformed. The authorities were running a clean-up campaign to rid the city of its rubbish, and even the Prime Minister took to the alleys with a broom. Street traders were also swept away, and without its secondhand clothes, tobacco, alfalfa and impromptu poets the suq outside my house was eerily quiet for the first time in centuries. There was no longer a smell of basil on the stairs. The transformation of San’a into a museum had begun, and I was glad not to be watching it.

Three days later we arrived in the small town on the Hadramawt coast which Sa’d and Muhammad had said was the main port for Suqutra. It was late afternoon and the sun slanted, mellifluous, across a broad bay. The only craft were a few hawris, slender, sharp-nosed fishing boats. They hardly moved, so calm was the ocean.

At a tea-house that smelt of fish we asked about a boat to Suqutra.

‘You’re in luck. There’s a sambuq leaving tonight.’

Kevin and I looked at each other. It couldn’t be this easy.

A tuna appeared in the doorway. ‘It’s going to Abdulkuri, not Suqutra,’ said the boy who was carrying it. Abdulkuri is a small island in the Suqutra group but more than 60 miles closer to Africa. Some 250 people live on its volcanic coast in, I had read, ‘extreme poverty, cut off from the world, and suffering great distress’. It was the sort of place where you could get stuck for a long time. Tempting as that sounded, we shook our heads.

‘I’ll take you to Salim bin Sayf,’ the boy said. ‘I think he’s going to Suqutra soon. And he’s the best nakhudhah anywhere.’ Nakhudhah! That was a word with resonances! Persian for a ship’s captain and used in Arabic since the time of Sindbad, it recalls the days before the sextant, before even the lodestone, when ‘the Junk and the Dhow, though they looked like anyhow,/ Were the Mother and the Father of all ships …’

The boy took us to the far end of the street, past the school and up an alley where we knocked on a plywood door. Goats wandered past masticating nonchalantly; there was that rich Hadrami dung-and-tobacco smell and a pinch of salt-sea shark. Salim bin Sayf stuck his head through the door, bushy bearded, rheumy in the eye, the very picture of the best nakhudhah anywhere. He was sailing for Suqutra on the eve of Wednesday. At first suspicious of why we should want to go by sea, he softened when we explained that as foreigners we’d have to pay for the plane tickets in dollars, which meant they would cost us five times what they cost Yemenis. Anyway, the plane was full.

We asked how much he charged. Salim tugged his beard, the gesture that means ‘Shame on you!’, and named a price less than the cost of a couple of afternoons’ qat.

‘And what about food?’

He looked us up and down. ‘Can you eat what we eat?’

I tugged an imaginary beard. Salim chuckled and we said goodbye, until Wednesday evening.

On our way back to the port we shared maritime experiences. I had pottered around the cliffs of Donegal in a skiff and had spent a pleasant weekend pub-crawling the East Anglian coast on a Cornish crabber. In the East Indies, Kevin had sailed in a Bugis craft of immaculately polished teak with a prow like a stiletto and a cushion-strewn poop. I could picture him, lolling on a burnished throne, a pipe, perhaps, of opium in his hand.

‘Don’t expect anything too smart,’ I warned. In the early seventeenth century the Sultan of Suqutra had ‘a handsome Gally and Junk of Suratt’. But that was in the golden age of Arab seafaring. I felt Kevin might be harbouring grand hopes. ‘And the loo will be a tea-chest with a shitty hole, lashed over the back end.’

Down on the beach once more, we scanned the water. There was no sign of an ocean-going vessel. Perhaps we’d got the day wrong. ‘He did say Tuesday evening, didn’t he?’ Kevin asked.

‘No. He said Wednesday evening. But that means the eve of Wednesday, which is Tuesday evening. I checked with him and he said, “Yes, I mean Tuesday.” ’

‘You don’t think he meant the eve of Tuesday? If he did, then we’ve missed the boat …’

A child was standing in the shallows, lazily casting a weighted net into the water again and again. We walked over to him, fearing the worst. ‘Where’s the nakhudhah Salim bin Sayf?’ I asked.

‘I don’t know.’ He cast the net again. ‘But that’s his sambuq out there.’ The boy pointed to a boat that seemed little bigger than a hawri. The only difference was that it has a single forward-raking mast. The hull was painted red and yellow.

‘That’s the one that goes to Suqutra?’

The boy stopped in mid-cast, looked at us strangely, and nodded.

The seas around Suqutra are notorious for their unpredictable winds and mountainous swell. I remembered reading an old verse, in a book of cautionary tales for sea captains, which spoke of the perils of navigating between the island and Cape Hafun – the tip of the Horn of Africa:

Between Suqutra and Hafun’s head,

Pray your course be never set …

Somewhere out in the 260 miles of open ocean that separated us from Suqutra, Leviathan was licking his many pairs of lips.

We tracked down Salim bin Sayf at a wedding party. The whole town was invited and the main street had been turned into a concert-hall. The band sat on a stage in front of a painted backdrop showing an idyllic bay. Not far behind that there was an idyllic bay, not that you could see it in the dark. The music had a hillbilly beat, and young men came to the front in twos and threes to perform a hip- and shoulder-wiggling shuffle.

Kevin and I watched for a while then strolled back to the beach. The sea was black, but in the glow from the town slender forms of beached hawris could just be made out. Knots of men sat in the sand, chatting and smoking; others had wrapped themselves in sheets and were sleeping. We were joined by a middle-aged man who introduced himself as Muhammad Ba Abbad. Muhammad worked as a surveyor in the Emirates but was a native of the town who knew the sea as well as anyone. We told him we thought the sambuq was a bit on the small side.

He laughed. ‘Actually it’s one of the bigger ones. But don’t worry, the dangerous season’s over. It begins with the star of al-Nat’h in the horn of Aries, and ends with al-Ramih, Arcturus. They say idha ma natahsh, ramah, “If it hasn’t butted, it’ll kick.” This year the sea kicked – the storms came at the back end of the dangerous period. It will be calm for you, in sha Allah.’ Now, at least, it was calm, the sea susurrating almost inaudibly on the strand. ‘But you’ll still be puking from the smell of sif.’ Sif, used for protecting wooden hulls against rot, is made from ‘the innards of sharks, simmered in earthen pots until the flesh dissolves and turns to oil’, according to a medieval Adeni recipe. Eventually, the crew arrived and Muhammad wished us a safe voyage. We boarded a rocking hawri and set out into the black, the sounds of the wedding fading behind us.

On board the sambuq, which rolled even in this calm sea, a paraffin lamp was lit. A smear of light revealed a deck crowded with boxes, oildrums, ropes, anchors and bodies. There were fifteen other passengers, already embarked and asleep. That made twenty-three of us in an open thirty-five-foot boat, and the voyage would last two nights and a day.

The nakhudhah Salim was last on board. Bare-chested, issuing orders, he had somehow grown bigger and younger. A crewman skipped below deck and cranked the engine to life; Salim produced a compass sitting on a bed of woodshavings in a twine-bound box. He lined the box up with the mast and secured it with a few nails banged into the deck. At one in the morning we weighed anchor and headed, on a course of no degrees, for the ocean.

Gradually, activity subsided. The crewmen joined the rest of the sleeping bundles. Kevin stretched out too, his head cushioned on a tin of Telephone Brand ghee. Only a small space was left, next to the nakhudhah, and I propped myself on the gunwale and watched the lights of the town grow more distant.

Salim told me about his family. His father and his ancestors had been skippers here for as long as anyone could remember. His mother was a Suqutri from Nujad on the island’s south coast. The lamp was turned low. Salim kept his eyes on the stars. A cord, looped round the hewn tiller, tightened and then slackened in his fingers.

‘Nujad is where they come down the mountains to pasture the flocks. Lubnan, my father calls it.’ Lebanon, the land rich in milk. He refolded the tarpaulin he was sitting on and wrapped himself in a large striped blanket. ‘They make these in Suqutra. You see, everything comes from their flocks – milk, butter, cheese, wool, meat.’

‘What about fishing?’

‘There’s some. The real Suqutris are bad sailors.’

I looked back to where the town had been, and gone. Three in the morning. The painted backdrop of sea would be lying rolled up. The real sea under us was more jelly than liquid. Blackcurrant jelly. The bride would be lying, deflowered. Tenderly, I wondered, or mechanically? Beneath me the diesel thumped yet, somehow, did not disturb the calm.

‘That’s why we Hadramis marry Suqutri girls. It puts some salt in their blood. I’ve got a wife on the mainland and a wife in Nujad.’

I stretched out, feet hanging over the engine, head next to the compass.

‘Look!’ Salim whispered.

There, to starboard, a pair of porpoises were shadowing the sambuq. They leapt, silent and ghostly in the starlight, disappearing with a flicker of phosphorescence at the end of each parabola.

Salim tapped my shoulder. ‘Listen: my father, when he was young, was out fishing with a friend. They were in a hawri, a long way out from the shore. Suddenly the boat turned over. It was a dolphin that did it, a big one. Anyway, the boat was sinking and it was too far to swim.’ He tightened the cord on the tiller. ‘But the dolphin saw what he’d done and came to them. He took them on his back and stayed by the boat until they’d baled it out. Then they got back in and returned to land. Glory be to the Creator!’

The porpoises had gone. Again I stretched out and began slipping away from consciousness.

‘When you go to sea,’ I heard Salim say, ‘the Angel of Death follows you.’

Salim was still at the helm when I awoke. Kevin was sitting upright, rubbing his eyes. ‘I’m bursting for a piss,’ he said. ‘What are you supposed to do? I can’t see one of those boxes.’ One of the crew, on cue, showed how it was done. Kevin changed into a futah. ‘Keep an eye on me.’

He picked his way across the sleepers towards the prow, squatted on a greasy gunwale and, gripping a stanchion, hitched up his futah. It took a long time. ‘God!’ he hissed, when he got back, ‘What do you do when it’s rough?’

But it was as calm as ever. The sea curdled where the prow cut through it, then recongealed in the sambuq’s wake. An odd flying fish shot out of the water like a spat pip. In such a sea, ‘without a stir, without a ripple, without a wrinkle – viscous, stagnant, dead’, perhaps at this very spot, Conrad’s Lord Jim had abandoned the doomed Patna and her eight hundred pilgrims.

Over to port a ship was approaching, a phantom, silvery in the rising sun. Salim steered across her course. No sound came from her, though the decks and companionways were packed with people, standing silent and immobile as statuary: ‘there were people perched all along the rails, jammed on the bridge in a solid mass; hundreds of eyes stared, and not a sound was heard … as if all that multitude of lips had been sealed by a spell’. God knows, it was the Patna herself. It was the only other vessel we were to see.

Our six-ton sambuq, the Kanafah (no one ever used the name, and even Salim had to think before he remembered it), had been built a few years ago in al-Shihr. Below the waterline the hull was of teak. For the rest a cheaper hardwood, jawi, ‘Javan’, was used, with pine planking for the deck. Powered by a 33-horsepower Japanese engine, she was also lateen-rigged like all Arab craft but her sail would only be used in emergencies. ‘Diesel engines started coming in in the mid-fifties,’ Salim said. ‘By about twenty years ago they’d taken over completely. If we were under sail it would usually take about five days to reach Suqutra. In weather like this, much longer.’ I remembered reading about the leisurely pre-diesel voyages of the great ocean-going baghlahs of the Arabian Gulf, when the ship’s carpenter would have enough time to build a smaller vessel on the main deck, to sell when the baghlah reached her destination; and I had a vision of a series of ever-diminishing carpenters building ever-diminishing boats, each on the deck of the other, and so on ad infinitum in a windless sea.

Ten feet below the surface, red-shelled crabs, dozens of them, were heading towards the mainland, slowly, as if through aspic. They had a long way to go.

The cook, a pudgy boy, appeared from a hatch towards the fore with a pile of pancake bread and a thermos of milky tea. Most of the passengers who had not already risen surfaced at the smell of cooking, and a queue formed to pray in the single free bit of deck. A couple of others slept on. One, I was sure, I saw for the first time only when we dropped anchor off Suqutra.

The passengers fell into two groups. There were the outsiders and semi-outsiders, like Hadid bin Bakhit bin Ambar, another Hadrami with a Suqutri mother. Most Arabic personal names have a meaning, like ‘Handsome’ or ‘Faith’. Hadid’s meant ‘Iron son of Lucky son of Ambergris’.* Hadid had lived in Kuwait and was going to spend a month in Suqutra, his first visit in seven years. Of the other non-Suqutris, one was a crabby old Mahri trader with jug-handle ears that stuck out from under a white crocheted cap. He had a store on the island and most of the cargo below deck, sacks of flour and sugar, was his.

The Suqutri passengers were silent men with wild, auburn-tinted hair, wrapped in huge Kashmir shawls and looking queasy. If they did speak, it was in undertones, all aspirants and sibillants like the soughing of the wind in treetops. It reminded me of Hebridean Gaelic. To a speaker of Arabic, the Suqutri language sounds like a distant and dyslexic cousin. But occasional words are familiar and, in time, I realized that it shares with the Raymi and Yafi’i dialects of Yemeni Arabic the past-tense k-ending, another revenant from the ancient languages. Island and mountains, cut-off places: the Celtic fringe of Arabia. ‘There are still some Suqutris in the interior’, said Hadid, ‘who can’t speak Arabic. Thirty years ago, perhaps ninety per cent knew hardly any.’

One of the Suqutris spent most of his time as the sambuq’s figurehead, his legs wrapped around the bowsprit, singing. It was a four-bar melody, full of quarter-tones and flicked grace-notes, repeated, da capo, without let-up, to the rhythmic chug of the diesel. Salim said it was poetry. With a wavy mane of hair, a high forehead joining his nose in a single arc, and flaring nostrils, he looked like one of the Trafalgar Square lions. There was, too, something archaic in the profile, an eerie resemblance to the early Sabaean bronzes.

‘There are some strange-looking people in Suqutra,’ Salim told us. ‘The mountain tribes don’t mix much with outsiders.’ I remembered the people described by Sir Thomas Roe, who anchored off Suqutra in 1615 with his ships the Dragon, the Lion and the Peppercorn on his way to visit the Mogul Emperor of India. The Suqutris, he said, were divided into three groups, Arabs, slaves and ‘savage people, poor, leane, naked, with long haire, eating nothing but Rootes, hiding in bushes, conversing with none, afraid of all, without houses, and almost as savage as beasts, and by conjecture the true ancient Naturals of this Iland’.

Hadid didn’t agree that all the mountain people were shy of strangers. ‘There’s a place in the east called Shilhal’, he said, ‘where they’ve got fair skin and blue eyes. Just like you nasranis. You tell me where they got them from.’

‘Greeks?’ I suggested, ‘Shipwrecked mariners, Portuguese?’

‘Oh, they’re probably Crusaders,’ Kevin said ironically. ‘They seem to have got everywhere else.’

We made a mental note to visit the nasrani-like clan of Shilhal.

The sun crossed the sky, planishing the surface of the ocean like a coppersmith’s hammer. The Kanafah seemed over-crewed. One of the seamen put out a line, but nothing bit all day. Another, whose father had been a nakhudhah running paraffin to al-Mukalla for the Provençal-Adeni merchant Besse, lashed his shirt to another line and threw it over the side for the sea to wash. The only one who seemed fully occupied was the cook, who popped up again from below deck, like a pantomime genie through a trapdoor, bearing a great plate of rice and something he’d cut off an object hanging from the mast. If the object looked like anything it was a bit of old tractor tyre, but it turned out to be dried shark. After lunch I curled up in the bows and fell asleep to the song of the figurehead.

Sleeping was the main occupation on board. Kevin had fallen in with the rhythm and settled down for the night soon after evening prayers. Salim was at the helm again and I joined him, curious to learn more about techniques of navigation and whether much knowledge had been passed down from its heyday among the Arabs, the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. During this period, the celebrated pilot Ahmad ibn Majid led the field in a science in which mnemonic verses played the part of charts, and nakhudhahs held international conferences to discuss abstruse points on winds and stars.

‘We all know Ibn Majid,’ Salim explained. ‘Nakhudhahs consider him their ancestor. But now we rely on the compass. See, we started on a course of no degrees. Now it’s 135 degrees. By the time we reach Suqutra we‘ll be following a course of 150 degrees. If we went in a straight line, the current would take us into the ocean.’

‘And if there were no compass?’ To describe, without one, this huge westward-curving trajectory and arrive at a particular spot on a small land-mass in a vast ocean seemed an impossibility, like shooting an arrow at a tiny and invisible target. The sambuq had no radar or radio, and I imagined us overshooting Suqutra, ending up in Madagascar, or wandering the Indian Ocean far from the shipping lanes until the fuel ran out and we were carried past Reunion and the Prince Edward Islands, on and on, towards the ice floes of Antarctica.

‘Ah, every nakhudhah knows the stars. Those two point to Mirbat in Oman; those, to Qishn; then’, he went on, running his finger across the sky, ‘Sayhut, Qusay’ir, al-Shihr, al-Mukalla, Aden, Djibouti, Berbera, Abdulkuri, Qalansiyah, Hadibu. Every three hours you must change to a new pair of stars as the old ones fall away.’

I lay back, leaving Salim at the tiller, wrapped in his woollen shamlah. The old familiar constellations above me were rearranging themselves. Where the Plough, Orion and the Little Bear had been, there was now an array of new signs above like the overhead gantries at a motorway interchange, but on a cosmic scale.

I was awakened by the dawn call to prayer, which Hadid chanted before the mast in a thin voice as penetrating as an alarm clock’s bleep. A change had come over the sea. The dead, viscous surface was now alive. We were still six or seven hours off Suqutra, but even this far away the invisible island was loosing its aeolian forces on the water. One by one passengers and crew relieved themselves, abluted and prayed. Kevin and I were both unnerved by the business of urinating. Over breakfast Hadid told us that the sea off Suqutra was always za’lan, angry (the dictionary definition is ‘Lively. Writhing in hunger’). ‘This is nothing. Often the waves come over the deck. I’ve done this journey many times, and I’ve usually been soaked from start to finish.’

Throughout the morning the unseen presence before us made itself known by great banks of clouds and a headwind that brought boobies and terns with it. I imagined we might scent Suqutra before we saw it. Hadid laughed at the idea. ‘If you smell anything, it’ll be goats. There’s still a bit of frankincense-collecting, but the trade’s almost disappeared.’

‘What about ambergris?’ Kevin asked.

‘I’ve never found any,’ said Hadid, ‘but they say that about twenty years ago a Suqutri came across a huge lump on the beach. He thought it was tar from a steamer and used it to waterproof the roof of his hut.’ He shook his head slowly, looking towards the queasy men in their shawls. Suqutra was beginning to seem a sort of paradise on earth, I said, a land abounding in milk and meat where precious gums dripped from trees and the sea cast up costly unguents unbidden.

‘Paradise …’, said Hadid, smiling at the clouds, ‘paradise without doctors or medicines, without communications for half the year. It’s only you nasranis who find paradise in this world.’

And then it appeared. First just a smudge on the horizon, it resolved into a line of cliffs with a streak of white sand at their base. We headed for a spot where the line dipped. The dip became a broad strath carpeted in seamless green, its sides framing a foreground of palms and the low cuboid houses of Qalansiyah. Hadid hoisted his red-checked headcloth as an ensign and we dropped anchor in water of incredible clarity. A couple of sambuqs and a few hawris bobbed around us; shoals of fish darted under the hull. A hawri came and took us to the shore, where Egyptian vultures the colour of an octogenarian smoker’s hair stood among green weed, unfazed by a crowd of children who gathered to study the new arrivals. Sa’d, the high-school graduate with the enchanter’s eyes, was there too with a notebook to list the incoming goods. Salim, Hadid and the others were greeted with a gracefully choreographed double nose-touch accompanied by little sniffs. Sa’d and I shook hands.

On board, Kevin and I had felt no discomfort from the boat’s motion but now, on dry land, we were both hit by the effect of thirty-six hours on the ocean. My brain seemed to swivel on gimbals inside my skull. Ali bin Khamis bin Murjan (Ali son of Thursday son of Coral), one of the passengers and a native of Qalansiyah, took pity on us and invited us home. He led us along narrow alleyways where the ground quivered and the walls throbbed. When we arrived at his house, the only two-storey building in the town, he took us to an airy upstairs room with yellow walls and a repeating calligraphic frieze, the Islamic creed stencilled in pink. It just wouldn’t stay still. We were ordered to lie down.

Half an hour later I woke to the sound of low voices. A woman who must have been Ali’s mother was talking to him in a stream of Suqutri and Arabic. In early middle age, she was unveiled and handsome in a strikingly Iberian way – the sort of woman you might run into in a smart Lisbon department store, I thought, remembering the Portuguese connection.

Kevin was stirring. There is no god but God still undulated slightly above him; however, the worst of the delayed motion-sickness had worn off. It was then that I realized something was different: there had been no interrogation. Usually in Yemen a newcomer, and particularly a foreigner who speaks Arabic, is subjected within moments of arrival to intensive questioning on every subject from the Resurrection of Christ to the Duke of Edinburgh’s precise constitutional status. There is rarely any other motive than a wish to break the ice, and to this end the interrogation is very effective, preferable by far to an embarrassed Anglo-Saxon silence. It is a small price to pay for often bewilderingly generous hospitality but, if all you want to do is sleep, the need to perform can be exhausting. Here, though, no demands had been made on us. Writing of his visit to the island 160 years before, Wellsted said of the Suqutris that ‘the most distinguishing trait of their character is their hospitality’. Nothing has changed.

The only losers in the hospitality stakes are the goats. That evening Ali slaughtered one for the Kanafah’s crew and the two nasranis. It was a skull-smashing, cartilage-wrenching occasion, a hands-on lesson in caprine anatomy. An hors-d’oeuvre of bones was served on a palm-frond mat by Salim, who cracked the head with a mighty double-fisted blow and shared out creamy morsels of brain. Then followed the meat itself and intestines stuffed with fat. The flesh was delicious, almost gamey, and an improvement on the days of Captain John Saris, who wrote of the goats of Suqutra after a visit in 1611 that ‘most of them are not man’s meat, being so vilely and more than beastly buggered and abused by the people, so that it was loathesome to see when they were opened’. (The comment is strange – the Suqutris are indulgently gentle with their animals.) Ours was a Homeric feast, its victim the first of a hecatomb which was to fall as Kevin and I wandered the island.*

Salim said it was time for bed. After all, for the last two nights he had, Odysseus-like, ‘never closed his eyes in sleep but kept them on the Pleiads’. Before turning in he spoke to Kevin and me. ‘Come with us tomorrow. We’re going round the island to Sitayruh, my mother’s village in Nujad.’ We agreed eagerly. ‘It’s a ten-hour journey so we must be up before dawn. Sleep now.’ We bedded down with the crew in Ali’s courtyard. With no diesel thumping beneath me, the silence was as profound as the ocean. There was only a single heroic belch answered by a hushed ‘Hani’an!’ – bon appétit in reverse.

At 4.30 in the morning the cold was bitter. The sun rose as we weighed anchor and headed west. Far off to starboard a pair of rocks jutted out of the sea, fondled by rosy-fingered Dawn. Salim said they were called Sayyal, but I later came across their more poetic name in an early nineteenth-century rhyming pilot’s guide: Ki’al Fir’awn, The Pharaoh’s Bollocks. We passed the headland of Ra’s Biduh and crossed the broad bay of Shurubrum, backed by steep green hills.

Here a gurgle from the prow marked the slaughter of another goat, a present from Ali Khamis. When I went to investigate, its skin was almost peeled off and the deck was running in blood. Its dismembered carcass disappeared below with the cook while the skin was draped, Argonaut-fashion, over the bowsprit in front of the singing figurehead. By the time we rounded Shu’ub, the island’s westernmost point, the meat was cooked and we breakfasted at the captain’s table – again, a palm mat – on pancakes, tripe wrapped in small intestines, and liver. Salim, with the help of a spanner, extracted a single quivering column of marrow from a femur and then presented it to Kevin and me, performing the operation with his usual combination of brute force and fastidious delicacy.

Our course took us under the lee of the cliffs, disturbing the cormorants that nested in the rock-face. Over to the south-west Salim pointed out two distant islands, the Brothers, rising from the sea like plinths waiting for statues. ‘That’s where I go shark-fishing. One of them, Samhah, has a few people but Darzah, the other one, is covered in rats.’ A British expedition in the 1960s was unwise enough to camp on the second island; they spent the whole night fighting off its inhabitants.

At the village of Nayt, a few huts on the beach, we dropped an oildrum of salt into the sea; a boy swam out and pushed it back to the beach. Further on at Hizalah, where half a dozen tiny stone cabins clung like barnacles to a cleft in the rocks, we shouted for twenty minutes before anyone answered. Eventually, another boy swam out and climbed into the sambuq. He stood on the deck, dripping, like the half-seal half-man amphibians of Norse legend. After a panted exchange in Suqutri he plunged back into the aquamarine water and fetched a hawri, in which we deposited a spare anchor.

Soon after Ra’s Qutaynahan the cliffs rose again, 1,600-foot walls striated horizontally and falling sheer into the sea. Here and there, high up, there was an inaccessible cave, curtained by creepers. The noise of the diesel bounced, amplified, off the rock; there were no birds. The crew ceased talking and stared up at the caves, as if half-expecting an Arabian Scylla to pop out.

At last, where a tiny settlement called Subraha appeared at the foot of the cliff wall, Salim broke the spell of silence. ‘This is the start of the Nujad Plain, where people bring their flocks down from the mountains.’

Kevin pointed out that there didn’t seem to be any way down. Ahead, the cliffs marched beyond the horizon, sheer and uninterrupted. It was now midday and the bloated shapes of clouds, tethered like balloons in the windless air, were projected on to the escarpment.

‘Oh, there are paths, not that you’d call them that,’ Salim said. ‘The ledges are sometimes only this wide.’ He showed a span. ‘In some places they use ropes. And their flocks can be several hundred head.’

Slowly, the plain broadened, and at Bi Zidiq, another minute hamlet, the figurehead jumped over the side and struck off for a shore of hound’s-tooth rocks. We watched him drag himself out – with difficulty, as a wind had begun to stir up the swell. Soon he was back in a hawri and the last few passengers left. Lunch was rice and the remains of the goat. This time, Salim produced a hatchet from his toolkit-cum-batterie de cuisine to get inside the skull.

The sambuq’s shadow began to lengthen on the sea bed, crossing white sand and black rock beneath water so transparent we seemed to be in levitation. Kevin hung over the matting sides trying to photograph a school of porpoises. A couple of pale, yard-long turtles glided beneath the hull with indolent flicks of their flippers, descendants of the ‘true sea-tortoise’ for which Suqutra was famous in the days of the Periplus.

We arrived at Sitayruh an hour before sundown. The shoreline was busy, a metropolis after so many hours of near-empty coastline. Men staggered under unidentifiable loads, draped across their backs like huge rubbery cloaks, which they tossed into a beached hawri before returning to reload at the little headland that formed the bay’s eastern arm. Landing was precarious and we had to jump, between breakers, from the boat which took us ashore.

Kevin went to investigate the loads. They turned out to be sharks, split kipperwise, salted and dried. I found him examining a pile of fms, which they call rish, feathers. Some were enormous and had been cut off the hammerheads and maicos whose flesh was stacked nearby. While this is exported to Hadramawt, the Suqutris themselves are said to be fond of the shark’s liver, salted and preserved in its stomach. The fins were sold on the mainland for 1,200 shilins a kilo, around $30 at the time. ‘We know they go to the Far East,’ said a voice from beneath one of the sharks, ‘but what do they do with them? They must be crazy to pay that much. Praise God!’

I explained that the fins were made into soup. ‘And they pay even more for birds’ nests.’

‘Birds’ nests? The cliffs here are full of them!’ the man exclaimed. Kevin described the collection and auctioning of nests which he had witnessed in a Sarawak cave. The Suqutri listened, then staggered off under his gruesome mantle, muttering the only possible response: There is no strength and no power save in God.

Hadid, who like Salim also had a wife here, appeared and led us over the dunes to the village. The houses were compounds of single stone rooms, bewigged with palm-frond thatch and surrounded by fences of the same material. We sat in Hadid’s yard, eating dates and drinking coffee, until the evening prayer. A bowl of rawbah was passed round. Rawbah is milk after the fat has been removed to make ghee; it is poured into a goatskin, which is inflated with a lungful of air and sealed, and then left to turn sour. Slightly pétillant like a Lambrusco, the Suqutris are addicted to it. At first we found it delicious; a fortnight later we were sick of the taste.

Hadid, Kevin and I went that night to Salim’s house, where the crew and most of Sitayruh’s adult male population sat waiting for more goat. The large compound was mostly in darkness, with a couple of lanterns making feeble pools of light. When the food arrived, we ate in silence while Salim carved bite-sized chunks of meat with which he constantly replenished a pile on top of the huge plate of rawbah-soaked rice. After supper, we talked about magic. The subject seemed appropriate: Sitayruh was the sort of place that would breed spells.

‘There’s a man in al-Shihr’, pronounced Hasan, one of the Kanafah’s crew, ‘who writes charms. He can do one that guarantees you a forty-ton catch of shark!’

Salim scoffed. ‘I suppose you’d believe what they used to say about Ali Salim al-Bid’s father, that he could sell you a charm that made girls think they were walking in water so they’d lift their skirts.’ (The idea, at least, had a Qur’anic basis in the account of the Queen of Sheba’s visit to Solomon, when the prophet made her walk across a mirror-like floor and she bared her legs.)

I asked about witch trials. Snell, a colonial official, gave an account of the procedure in the mid-1950s: a suspect was first subjected to an oral inquisition by the Sultan then, if he decided there was a case against her, she was tied and weighted with 8lbs of stones; if she sank three times in three fathoms of water – the inquisitors pulling her up with a rope each time – she was innocent; if she was seen to be floating in an upright position, she was held to be a witch and exiled to the mainland. Not so long ago she would have been hurled from the cliffs. At another trial, in 1967, a guilty woman is said literally to have sprung out of the waves. Salim’s guests confirmed that the trials had continued until recently. Nowadays witches go about their business more or less unmolested.*

‘It’s since Unification that the old customs have really been dying out,’ Salim said. ‘People come from the mainland to teach the Suqutris about Islam. Take circumcision, for instance. Do you remember the boy who got off first at Bi Zidiq? I saw him circumcised a few years ago. He was about ten at the time but, in the past, they used to circumcise young men not long before their wedding night. Well, long enough for the cut to heal.

‘This is what I saw: three boys were brought, as naked as when they were born, before all the people of the area – hundreds of them, men and women. These guests had brought over a hundred head of sheep and goats, just as they would at a wedding. The boys’ hair was cut very short and their heads were covered with butter – I’ll tell you why in a minute. They were seated on a special stone while the circumciser, whom the Suqutris call mazadhar, did his job. Each boy concentrated on the mazadhar’s chest, or on some distant object, and I swear that not one of them flinched while he was cut. Not even a blink. Any sign of pain, any reaction at all, is a big disgrace to the boy and his people. That’s why they crop their hair and butter it, because if it were to stand up people would see that the boy felt fear. Anyway, immediately after each one was cut he jumped into the air three times, higher and higher until he jumped as high as himself. Then the boys ran together, with their blood still flowing, to a special hut a couple of miles away. Here they have to stay until the cut is better. They heal it with plants and hang bags containing a strong smelling substance – I don’t know what it is – under the boys’ noses. No woman may visit them there. This is what I saw; this is how it was with the Suqutris until not long ago. Wallah! Now, the religious leaders have stopped it because it is unIslamic.’

Public pre-marital circumcision, it seems, is another feature of the old South Arabian fringe. Wellsted noted it among the Mahris, and Thesiger records that the notorious ‘flaying’ version – removal of the entire skin down to the thighs – was practised in Asir. Now, for better or worse, it seems to have disappeared.

We talked of makólis, the traditional Suqutri magic-makers, and of sayyids, the incomers who had usurped many of their supernatural powers. The sayyid who built the main mosque in Hadibu, they said, woke up one day to find its roof miraculously completed overnight, and Johnstone reports that sayyids had taken over from makólis the power to control the wind. One of the villagers told us of the female jinn who roam the mountains at night. ‘And if you meet one,’ he said, ‘she sings to you.’ He sang, very softly, in falsetto. The tune had a lilt to it, something like ‘Girls and boys come out to play’, and it made the hairs on my neck stand up. I asked him what the words meant.

‘They mean’, he said, smiling, ‘ “I’ve been waiting for you so long. Now God has brought you to me, and I’ll have your flesh …” ’

The evening went on. Riddles were told, tongue-twisters recited in Suqutri, English and San’ani Arabic, everyone laughing at my attempts to produce a lateral sibillant. Gradually, conversation changed to Suqutri, then subsided, until you could hear the beating of moths’ wings against the lamp-glass.

Kevin edged closer to the bush, camera poised. The snake lay coiled and motionless, its grey and orange stripes camouflaging it against the twig shadows and sand. The lens was inches from it. ‘They did say there weren’t any poisonous snakes in Suqutra …,’ he whispered, without turning his head, ‘… didn’t they?’

‘Yes, but I’m taking no responsibility for …’

The shutter clicked, the snake reared, swayed, then looped off. We found out later that it was a harmless desert boa, probably of the type called Eryx jayakeri.

So this was the Nujad Plain, Salim’s land of rich pastures: a dry waste of dunes and low bushes.

We had set off early along the beach, then struck inland for Mahattat Nujad. ‘It’s an hour and a half if you take it easy. And Mahattat Nujad is full of shops. And cars. You’ll have no problems getting a ride to Hadibu,’ Salim told us. Five hot hours later we arrived at Mahattat Nujad. We had lunch – rawbah-soaked rice and dates followed by tea in old bean tins – in the police station, a room with half a dozen iron beds and a few well-gnawed foam mattresses. After the meal, we asked the policemen if there was a car to Hadibu.

‘There may be one.’ The ‘may’ was ominous. ‘In a couple of days.’ And shops?

One of the policemen sprang to attention. ‘What would you like?’

‘What is there?’

‘Biscuits.’

‘Anything else?’

‘No. Just biscuits.’

The policemen directed us to Halmah, another three hours to the east, which they said was full of cars and shops.

We passed the great palmeries of al-Qa’r, then re-entered scrub and dune country. Not long after the snake encounter, we saw a large settlement and headed straight for it, abandoning attempts to follow the track. At last, nine hours after leaving Sitayruh, we arrived in the village of Halmah. Some children were playing in a dry wadi bed; when they saw us they ran, blubbing, for the village. We followed them and found a pick-up. One of its wheels was off and a man was belabouring the hub with a spanner. Yes, he was going to Hadibu in the morning, if he could fix the wheel; we should stay the night with him.

Ali Shayif was a Dali’i from north of Aden who had come to Suqutra on military service, married a local girl, and stayed. He was part-owner of a fishing-hawri but now most of his income came from trucking. His sole reason for settling here was that he liked the place; in this he probably resembled generations of outsiders who, like Salim, Hadid and their forebears, have been enchanted by the island and have intermingled with the coastal population. ‘The real Suqutris’, Ali said, ‘are the mountain badw.’ He went on to repeat the story about the blue-eyed tribe of Shilhal. Hadibu, he said, was full of slaves.

That evening Kevin and I bathed at a well just outside the village, drawing the water in a bucket made from an old inner tube and decanting it into hollowed-out boulders. Goats came and drank our bathwater, then some men joined us and the village idiot crept up and poured a bucketful over me from behind, just after I’d dressed. They went off, laughing, to pray. Back at Ali’s I hung my sodden shirt and futah on the palm-frond enclosure fence and we stretched out in the guest room. Ali caught a tiny bird and evicted it; it was back immediately. I fell asleep listening to it fluttering in the roof beams.

The crossing of Suqutra to Hadibu, a direct distance of around 24 miles, took four hours. It could have been quicker, but Ali had to stop time and again to unblock his petrol filter or beef up the truck’s sagging springs with wooden wedges, banged in with stones. The steering had an alarming leftward bias but no one else seemed worried. Our fellow passengers included an old man with a beard; it was patriarchally long and brightly hennaed, and with his tawny face and green crocheted cap he looked like an upside-down traffic light. A slightly younger old man had a thorn deep in his foot, and whenever we stopped he tried to excavate it, groaning, with an iron spike. There was also a young man in cool-dude denims and shades who had a Nujad mother and an Adeni father. The cargo included several engorged goatskins. These, Ali explained, contained dates which had been stoned, left in the sun for a fortnight, then trodden underfoot. The necks of the skins oozed slightly and attracted flies, as did the younger old man’s foot.

We crossed the plain, heading for a break in the cliffs. Once through this, the scenery changed abruptly. The road followed a perennial stream lined with little date palms, while ranks of bottle trees marched across the slopes above. The place was full of dragonflies and pink-breasted pigeons; at intervals, herons stood staring into the water.

A series of steep switchbacks took us to a high plateau beneath the watershed. Here, there was another sudden change of scenery. The background was dominated by great humps of mountains, covered in green except where granite outcrops thrust through a scanty topsoil. Look upwards and you were in the Scottish Highlands, the Cairngorms, say, complete with shielings and thatched stone croft houses. Lower your gaze, and the vision was broken: the burns below were filled not with rowan and ash but with palms, and the foreground was a gravelly plain studded with euphorbia. It was like being in two places at once; or in Dictionary Land.

We followed another watercourse down to the eastern end of the Hadibu Plain, a great theatre crossed by wadis and backed on the south by a wall of gigantic granite spires, the ‘raggie mountains’ noted by Sir Thomas Roe. I remembered Wellsted’s drawing: it had not been fanciful. Two of the spires appeared to be joined by a bridge. Altogether, it was a most unlikely skyline.

Hadibu itself is a functional place. Its buildings are uniformly cuboid, except for the Communications Office, an edifice in late twentieth-century quasi-San’ani style with coloured glass fanlights. It was a reminder of where central power resides; architecturally, it was wholly out of place, and at the time it wasn’t even working as there was no fuel to power the generator. We cadged our way into the government rest-house. Some of its fittings had come from a wrecked German freighter. It had all the charm of a reform-school dormitory, and little of the hygiene. Goats wandered, farting, along the dark corridors.

‘That’s funny,’ said Kevin. ‘I’m sure I can hear a circular saw.’ Then we realized what the sound was: mosquitoes, clouds of them. It was still daytime. The whine was continual, and at sunset it rose in a crescendo that possessed your skull. The best feature of the rest-house was a powerful shower, but even under this there was no escape from the mosquitoes, which had developed the ability to fly between the streams of water.

We were surprised to discover some other nasrani guests – a pair of Frenchmen. When they said they were entomologists we thought they were joking. In fact they were deadly serious – a glimpse inside their room revealed a row of killing-bottles and swathes of netting. They were also equipped with the latest footwear and rucksacks and, according to their Suqutri guide, ate nothing but pills.

Hadibu’s main interest lies in its being a meeting place for all the elements that make up Suqutri society. There were traders with mainland ancestry, fishermen, and mountain badw with bare feet, knotty calves and shocks of hair; but no blue eyes. Many of the town’s resident population are negroes descended from sultanic slaves, and one of these took us to the palace of the last ruler, Sultan Isa bin Ali.

‘Palace’ is a misnomer for such a modest building. All the same, its former inhabitants had a distinguished history. As long ago as the time of the Periplus, Suqutra was subject to the King of the Incense Land, an area which overlapped with much of the territory under the later Mahri Sultanate of Qishn and Suqutra. The sultanic family themselves, the Al Afrar, are of Himyari origin and had been prominent at least since medieval times. The family tree, however, was very nearly extirpated in the sixteenth century when the expansionist Hadrami ruler Badr Bu Tuwayraq murdered all the Al Afrar males but one, as yet unborn. The child’s mother preserved some of his dead father’s blood and, when he was old enough, showed it to him to instill the spirit of revenge. Grown to manhood, he took a vow of celibacy which he would only break if he defeated the Hadramis. He also refused to shave, and as a result became known as Abu Shawarib, Father of Moustaches. Eventually, the blood feud was successful and in celebration Abu Shawarib had his first shave at Friday prayers in the mosque of Qishn. His vow of celibacy he broke more privately, and his descendants ruled on the Mahri mainland and Suqutra for the next four hundred years.

The last sultan was – despite his martial ancestry – a mild and undistinguished-looking man. He bothered little about the more modern accoutrements of state. It is said that, in the absence of a sultanic seal, he stamped the scraps of paper which did for his subjects’ passports with the bottom of a coffee cup. Photographs taken during a British administrator’s visit in the early 1960s show him peering warily from beneath an enormous Saudi iqal, surrounded by a handful of courtiers and flunkeys. These included the executioner, a huge slave with severe scrotal elephantiasis. The Sultan’s procreative powers were considerable: one of Naumkin’s informants, a daughter of Sultan Isa who now works as a midwife, stated that she had one full brother and twenty-six half-siblings on the island alone, not counting those who had emigrated after 1967. The Al Afrar were making up for nearly getting wiped out.

As we neared the sea, the houses, built of coral stone, became more ramshackle and lost themselves among the palm groves. The palms, in turn, ran into the water in a maze of dead-ends and paths where we had to wade through little estuaries. Some of the houses had miniature gardens growing a few tobacco plants, carefully fenced off from the omnipresent goat. There was a perplexing lack of demarcation between land and sea, an amphibious mingling of humus and spume.

Back in the main street a crowd had gathered, and I squeezed in to see what had drawn them. A man was butchering an upturned turtle, slicing round the carapace as if opening a can. In deference to Islamic precepts he had cut its throat, but inexpertly, and every so often the turtle gulped and waved its flippers. There was a strong sea-smell, and I remembered the pale, graceful creatures gliding beneath the sambuq off Sitayruh. They would eat the meat; the shell, which in the days of the Periplus would have been exported to the cabinet-makers of Rome or Alexandria, was going to be the roof of a chicken coop.

The ‘raggie mountains’ beckoned, and next day we crossed the arena of the Hadibu Plain. At the foot of the great shattered grandstand that backed it the going got rougher; the Hajhir peaks, said to be one of the oldest bits of exposed land on Earth, are of granite, but with a limestone topping that has crumbled and fallen like icing from a badly cut wedding cake. Fragments as big as houses, riddled by erosion, were home to shaggy goats which sat eyeing us from their niches like dowagers in opera boxes.

We made for a gap far above. As we climbed, the vegetation grew denser, streams appeared in unexpected clefts, and now and again one of us would exclaim at some new discovery a spider’s web constructed on perfect Euclidean principles or a caterpillar in poster-paint colours. But it was the plants that fascinated us most. Whatever the Darwinian equations in force here, they had produced fantastical results. Nondescript bushes erupted into bunches of asparagus, trees turned into organ pipes then chimney-sweeps’ brooms, begonia-like flowers sprang from pairs of enormous conjoined boxers’ ears, whisky stills grew on the rocky crags. It was the botanical equivalent of Dictionary Land, the semantic jungle.

Sap, juice, resin and gum exude from branches and leaves so fleshy they often suggest the animal more than the vegetable. Several species are edible. There are tamarinds, grape-like berries, wild pomegranates and wild oranges. The last are a long way from their sweet mainland cousins: eating one is like biting into a battery. Frankincense and myrrh made Suqutra an important outpost of the thuriferous mainland regions in ancient times, and other species produce everything from incense-flavoured chewing gum to a kind of birdlime; Douglas Botting, leader of an Oxford University expedition to the island in the 1950s, noted that the juice of a certain euphorbia causes baldness, and was used to punish convicted prostitutes. Medicinal plants abound and the Suqutris use them regularly to treat scorpion stings, rashes and wounds. For over two millennia, one of the island’s most famous products was the Suqutri aloe. Its sap gained popularity in seventeenth-century Europe with the rise of the East India trading companies; it was exported, packed in bladders, to the relief of many a costive Restoration bowel or itching pile.

Nearer the crest, the vegetation thinned. Limestone gave way to naked granite. Suddenly, above us and sharply outlined against a brilliant sky, there appeared what at first seemed to be a line of giant conical funnels, their narrow ends stuck in the skyline. The upturned cones resolved as we got closer into branches, topped with spiky leaves and bursting out of a central trunk like fan-vaulting in a chapter house. Even after all the other weird flora, the sight was startling: it is with good reason that this, the dragon’s blood tree, has become Suqutra’s unofficial emblem. Botanically, and by one of those evolutionary quirks that makes the rock hyrax a cousin of the elephant, Dracaena cinnabari is a member of the Lily family. The common name, according to Pliny, derives from blood shed during a fight between an elephant and a dragon, from which the trees sprang. The story seems to be drawn from Hindu mythology, which might explain the Periplus’s reference to ‘cinnabar, that called Indian which is collected in drops from trees’. Perhaps in the Arabic name, dam al-akhawayn, the blood of the two brothers, there is an echo of Castor and Pollux, the twin sons of Zeus whose epithet, Dioskurides, is by coincidence the Classical geographers’ name for Suqutra. The etymology, complex as it is, seems to bear out other evidence of the island’s early trade. Dragon’s blood was formerly in great demand as an ingredient of various dyes, including those used in violin varnish and the palates of dentures; medieval European scribes made ink from it, and Chinese cabinet-makers used it in the famous cinnabar lacquer. Now, consumption is almost entirely local – the Suqutris use it to decorate pots and as a remedy for eye and skin diseases.

I climbed one of the larger trees, perhaps twenty feet tall to the flat bristly top of its canopy. Its smooth bark was marked by scabs where the resin had oozed out and coagulated. In one of the highest branches I found a tiny lump that had been missed by the harvesters. It was globular and brick-red, the outside matt, the inner face glassy where it had been stuck to the tree. I turned it over in my palm; then remembered the blood of the Arabian dragon in my father’s bureau.

On the far side of the col a valley opened out. We were at the head of Wadi Ayhaft, which drains down to the north coast west of Hadibu. The deep green of montane forest was framed by glittering granite. It was late afternoon, and we chose a campsite in a grassy meadow near a spring. The first mosquitoes were biting, and as I set up camp – by spreading an opened-out grain sack – Kevin went off in search of dead wood. A fire, he said, would keep the insects away. Half an hour later, he’d collected a good pile and arranged it into kindling, twigs and larger branches.

‘Where’s your lighter?’

I looked in my pockets. It wasn’t there. I hunted round the campsite. ‘I must have dropped it when I climbed the tree.’ We looked up to the ridge, disappearing in the failing light.

‘Forget it,’ Kevin said. He was silent for a long time.

The first thing I saw when I awoke at dawn, stiff with cold and dew, was my lighter lying in the grass beside me. Strangely, we were unbitten except for my left eyelid, which had swollen almost shut. I tried unsuccessfully to prop it open with a twig. Visual memories of that morning are therefore monocular, as if the mountains had been flattened into a painted set. But reality became painfully three-dimensional as we tried to climb the far side of the valley, making for a plateau that lay above. There seemed to be no path, and in the end the gradient and dense undergrowth defeated us and we retraced our steps.

Further down the wadi we rested in a dappled clearing between silver-barked trees, where the air was scented with mint and aniseed and the river tumbled below. It had the intense clarity of a Pre-Raphaelite landscape. But on closer inspection, everything was wrong. Upward-pointing leaves became fingers, as though a fleeing nymph had been caught, supplicating, in mid-metamorphosis. Brush your hand against that plant and it stung like a wasp. It was Arcadia but, again, unknown and disturbing. A feral goat came and watched us through slitty irises.

The valley broadened into parkland, but with great gnarled tamarinds in place of oaks. It was strangely empty. Not yet the Suqutri winter, the herds were still up in their high pastures. In one tree someone had hung a dead wildcat, not much bigger than a fireside tom but with powerful kid-killing claws. Upside down, with its face desiccated into an eternal smirk, it was a horrible parody of the Cheshire Cat.

Although it has the advantage of being totally dogless,* Suqutra’s mammalian wildlife falls short of its flora. The most interesting large mammal is the civet cat – not a cat but a member of the mongoose family. The Suqutri version is Viverricula indica, also known as the rasse. Civet, an ingredient of perfumes, is obtained in Suqutra by capturing the animal in a cage and then stimulating it until it produces a buttery secretion from a sac near its genitalia; it is then released to stagger off into the bush, exhausted but little wiser, as it will soon be caught again. We were curious to watch the operation, but civet production has declined in recent years and we drew a blank. Probably it was never as highly organized in Suqutra as elsewhere. A French physician, M. Poncet, mentions in his A Voyage to Aethiopia of 1709 that the people of Emfras, in the Gondar region, kept civet catteries up to a hundred strong: ‘once a week they scrape of [sic] an unctious matter which issues from the body with the sweat. ’Tis this excrement which they call civet, from the name of the beast.* They put it carefully into a beef’s horn, which they keep well stopt.’

The parkland came to an abrupt end. The valley sides closed in again and the wadi was all but blocked by a boulder the size of a large house. This, we realized, was what it was: the hollow underside was partly walled off and domestic objects – skins, a jerrycan, a mattress, blankets, clothes – hung at the entrance. We called but no one was at home. Inside, the ceiling was blackened by generations of cooking, and a battered tartan suitcase lay open on the floor. A side niche contained a padlocked green tin trunk. Some Suqutri herdsmen lead permanently troglodyte lives – the 1994 Yemeni census form included ‘cave’ under ‘Type of Accommodation’ – but this was a seasonal dwelling which would be occupied in the winter months only. Judging by the three criteria estate agents use to assess the value of a property – location, location and location – this one, situated above a waterfall with dwarf palms below, was truly desirable.

Kevin and I explored the theme of troglodytism as we skinny-dipped in a pool beneath the palms. We would move to Suqutra, find a cave, grow our hair, and live wild on goats, tamarinds and pomegranates. We fantasized about reviving the civet industry and installing little luxuries in our grotto: octophonic CD systems, tropical fish tanks, central vacuum cleaning, a Steinway grand. Alternatively, I would become a professional hermit; Kevin, as my agent, would tout for custom from the cruise ships, and tourists would part with hard cash to hear me spouting Delphic drivel out of a matted beard. With the right sort of PR and an appearance in National Geographic I would eventually be able to move to California, where grateful disciples would give me Cadillacs and clamour for phials of my used bathwater.

At the time, we were unaware of the flip-side of Suqutri rural life, the notorious di-asar, a fly which causes a potentially fatal infection by laying its eggs in the nose and throat at certain seasons. People protect themselves by wearing face-masks and amuletic beads, or by stuffing their beards into their mouths. No deaths have been recorded, so the prophylaxis must work.

We daydreamed the hot hours away until we realized that, with ten miles still to go back to Hadibu, we had to move fast. All the way down the wadi and along the coast Kevin, who had cavedwelling on the brain, sang snatches of ‘Wild Thing’ by The Troggs.

For the coastal stretch we were following Hadibu’s airport road, probably the worst airport road on Earth. Past Qadub, it fords inlets of the sea and climbs an appallingly steep pass up to the cliffs of Ra’s Haybaq, the Suqutri Tarpeian Rock from which witches were hurled. More cliffs tower above, riddled with caves; and between them, the bottle trees and the sea, the unsurfaced track is hardly less narrow than when Wellsted came this way: ‘A meeting of two camels on such a spot at night could scarcely fail to be fatal to one, or both.’ When you finally descend to sea-level again, the air is full of spray from the breakers that boom and crash in the undercut shore.

It was night when we reached the rest-house. The French entomologists had buzzed off on the morning flight, to be replaced by a lugubrious one-man wafd, or delegation, from the Ministry of the Interior. He divided his time between moaning on his bed, playing patience, and visiting the Hadibu pharmacy to get remedies for nausea, malaria, liver dysfunction, and an abrasion on the knee caused, he said, ‘by violent contact with a car door’. He was not enjoying his visit.

A few miles east of Hadibu, along a shore that crunches with a litter of shells and coral, lies the village of Suq, the island’s original commercial centre. Proof that it was so in ancient times came from excavations carried out by a Yemeni-Soviet team of archaeologists, who discovered fragments of a Roman amphora and other, possibly Indian, imported wares. Suq was still Suqutra’s capital when the Portuguese decided to occupy the island in 1507.

We had come to visit the fort of St Michael, which the Portuguese captured from a Mahri garrison and rebuilt. It lies on a spur of Jabal Hawari, the eastern limit of Hadibu Bay. Most of the inhabitants of Suq seemed unaware of its existence, but eventually a boy showed us the way. A scramble up a rough track brought us to a flattish area filled with the remains of a cistern, bastions and walls with rough lime-plaster facing that reminded Kevin of Albuquerque’s fort at Malacca. The ruins are unprepossessing but the view over Hadibu Plain is panoramic: below us, palms crowded round a lagoon where a wadi met the sea; eastwards stretched a broad bay backed by dunes, while in the opposite direction were the little gable-ended thatched houses of Suq and, in the distance, the palms and houses of Hadibu; to the south, a thick cloud blanket was pierced by the Hajhir spires; in front of us lay the ocean.

It seemed incredible that this was just one of an immensely long chain of coastal and island forts stretching from Mozambique via Muscat and the Malabar Coast all the way to the East Indies – that, for a few decades, the Indian Ocean had been a Portuguese lake. In the history of empires, this was one of the shortest-lived, an overblown thing like the monastery of Belem, outside Lisbon, where sober Gothic suddenly burst out in a Manueline nautical panoply of prows, poops, hawsers, anchors and dolphins – a building that stands as an allegory of the strange mix of crusading Christianity and naked capitalist expansion which propelled Iberians across the Old and New Worlds.

In Suqutra, the Portuguese expected to find a ready-made outpost of Christendom – the Gospels are said to have been brought by St Thomas, en route for India, while a sixth-century visitor from Egypt, the monk Cosmos Indicopleustes, noted that the Suqutris were Nestorian Christians of Greek origin.* But after a thousand years of increasing isolation, what the Portuguese found was not a long-lost and innocent version of Christianity but a syncretic nightmare. In a report to Rome, written after his visit in 1542, Francis Xavier complained that the Suqutris practised circumcision and that their forms of service had decayed into mumbo-jumbo incomprehensible even to their priests; in the following century, the Carmelite Padre Vincenzo commented that the islanders named all their women Maria, prayed to the moon for rain, and buttered their altars.

Moreover, the island was controlled by the Muslim ‘Fartaquins’ (Mahris – named after Ra’s Fartak in Mahri territory), and the Suqutris, preferring the devil they knew, offered no assistance to their new would-be masters. For a few years a Portuguese garrison mouldered unprovisioned up on its redoubt, until Suqutra was given up as a bad job. St Michael reverted to the Fartaquins, and Our Lady of Victory, the church which the invaders had converted from a mosque, returned to the embrace of Islam. Its plaster floor and column bases, excavated in the 1960s, were visible down below.*

Following this abortive occupation Suqutra, on the whole, eluded the imperialist grasp – though never quite as spectacularly as when it vanished out of sight of the Ayyubid fleet. The Portuguese returned on and off but never stayed; the Omanis attacked half-heartedly in 1669; the British tried it out as a coaling station before deciding on Aden, but their garrison succumbed to fever; the British Secretary of State for India suggested in 1943 that it might become an ‘adjunct’ to the Jewish state in Palestine and was told by the Colonial Secretary, in as many words, not to be such a bloody ass. The Suqutris of the interior, meanwhile, went on as before, collecting dragon’s blood and aloes, and milking their goats.

It was as if the Portuguese had been and gone and left nothing. Or had they? There were the blue-eyed people of Shilhal. Or could they be an even older genetic throwback, connected with the claim of Cosmos and later writers that the island had been colonized by Greeks? We hired another Salim, the owner of a battered green Landcruiser, to take us as far east as possible. We would finish the journey to Shilhal on foot.

There are no petrol stations on Suqutra – you just knock on a door and fill a jerrycan, if you’re lucky. Petrol is in short supply because of the difficulty of importing it, and costs up to five times the official rate in San’a; the cost of hiring a car is correspondingly high. After a lengthy tour of downtown Hadibu, we had a full tank and had also picked up a Hadrami, an official of the Central Organization for Control and Auditing, who wanted to come for the ride. The Hadrami said that hard statistical facts were difficult to come by on the island, although when I asked him how many cars he thought there were he replied, without hesitation, ‘Three hundred and one.’ Considering vehicles had to be brought to Suqutra lashed to the decks of sambuqs and then rafted ashore, it seemed a lot. Whatever the true figure, most were laid up through lack of fuel and spare parts.

An hour out of Hadibu, we were up on the high rolling moors, heading east under low cloud. Occasionally the cloud parted to light up a distant peak or hamlet, but at the village of Ifsir the rain set in, thick and wet. Here lived Salim’s sister, so there was another slaughter, another massive lunch of meat, rice and rawbah. Outside on the grassy roofs Egyptian vultures sat hunched against the rain; at every settlement here they sit and wait, ruffling their grubby plumage, patiently watching the houses until someone makes for the spot used as a public latrine. After he has defecated, the vultures gobble it up: a happy symbiosis but unnerving, for they encircle you as you squat, edging closer and closer.

From Ifsir to Kitab and Aryant the rain fell hard, turning the red road to mud and making the Landcruiser slip on the pass up to the higher plateau. But by the time we reached our destination, the village of Qadaminhuh, the rain had stopped. Kevin and I were dropped at a newly built house and wandered off into the sodden landscape while Salim went to find the owner.

Qadaminhuh is also known as Schools, from the big quadrangle of incongruous barrack-like buildings next to it. Here, a hundred or so weekly boarders live and study, boys from across this eastern region of Mumi. As we walked down the track towards the schools a fitful light broke through the cloud and a rainbow materialized. The place seemed deserted, but then a figure appeared from a doorway and headed towards us. He was dark-skinned and tall, clearly not a Suqutri, and before we could greet him he spread his arms in a wide sweep that took in the plain, the low surrounding hills and the rainbow, and said in rich and unaccented English, ‘Welcome to our … humble surroundings!’

Muhammad was an Adeni high-school graduate sent to do his obligatory teaching service on Suqutra. At first he had thought of it as a punishment posting. But up here in Mumi, he said, the scenery was so beautiful, the people so kind that you might imagine yourself in England. I agreed that even if the nearest country, in a direct line, was Somalia, you might be forgiven for thinking you were in northern Europe. ‘But in England you couldn’t just turn up on someone’s doorstep and stay for the night.’ Not in England, but perhaps further north. Again, I found myself remembering my months in the Outer Hebrides.

The rain – that at least could be English – came on again with sudden force. We shouted goodbye to Muhammad and ran for the house. Like the other houses of Mumi, this one was built of dry-stone and plastered on the inside with mud. Two columns supported a roof of irregular branches fitted together with great skill, and in the corners squinches were formed from wishbone-shaped boughs.

Sa’d, our host, expressed no surprise that two total strangers should be billeted on him. ‘It’s our custom,’ he said simply. In spite of his protests, Salim and the auditor left to drive back to Hadibu in the dark. We asked Sa’d about the blue-eyed people of Shilhal; he, too, was sceptical, and spoke of the place – only a few miles away as the vulture flies – as if it might not have existed.

We turned in early and spent a night disturbed by fleas and bedbugs. They (or, from the insects’point of view, we) were only a taste of what was to come.

By seven the next morning we were high in the uplands under a lowering sky on the way to Shilhal. The going was hard, over sharp rocks dotted with tiny alpines. Kevin found a beetle with iridescent peacock-blue wing cases splotched orange and yellow, a furry orange head and bright green feet and feelers; as it was dead he put it in his shirt pocket. Every so often we had to cross low walls of misshapen lichen-covered stones that were clearly very old: some authorities have taken them to be the ancient boundaries of incense plantations, but in fact they marked out claims allotted by the Sultan for the harvesting of aloes. The Bents, who visited Suqutra in the 1890s and must have seen them under the same grey sky, commented that ‘the miles of walls … give to the country somewhat the aspect of the Yorkshire wolds’. Once more, the sense of displacement was extraordinary.

We crossed a little dale, filled with basil and lemon-scented herbs, where we breakfasted on unripe tamarinds. Here, Kevin’s beetle suddenly came back to life. He put it on a stone, where it stretched its legs and tottered about: against the grey rock, its acid-trip colour scheme made it look like an escapee from Naked Lunch.

The valley marked the beginning of cattle country, and up on the far top we passed a herd. Like their cousins in al-Mahrah and Dhofar, these were humpless beasts no bigger than a small donkey; one of them glared at us and pawed the ground. Progress was slow, for at each hamlet we passed we were invited in for rawbah, and at lunchtime we joined an apparently never-ending feast in honour of a villager just returned from the Emirates. He sat in a corner, glassy-eyed, Buddha-like, mopping his face with a towel that said ‘Hawaii’ in multicoloured capitals, while plate after plate was set in front of him. They had killed a calf and seemed determined to finish it at one sitting, however long it took. I thought it was the prodigious quantity of food that made the prodigal so silent, until someone whispered to me, ‘He hasn’t been back for twenty-five years.’ It was, then, a severe case of culture shock. Or, maybe, time shock: over the last quarter-century, the Emirates had undergone as much change as Europe had over the last hundred years or more; in Mumi, almost nothing had altered. The man was like a long-term coma patient who comes round only to find that his dreams were more eventful than waking reality.

Groaning from a surfeit of rawbah and meat on top of green tamarinds, we set off again. Past the village of Ambali a wide, airy valley opened out. By now, the cloud had dispersed and the sun lit up lone clumps of bottle trees, megaliths with quiffs of foliage cut oblique by a sea wind. At the end of the valley the track climbed under a crag with walled caves at its base, then petered out. Before us, a few houses in a hollow, was the village of the blue-eyes: Shilhal. It looked no different from the other villages of Mumi. It felt like the end of the world.