Located in the NFF, 1991, box 22, Notebook 9 falls into three parts. The first thirty-three numbered pages are mostly indecipherable, cancelled drafting for the Massey Lectures that became The Educated Imagination, along with fragmentary notes on miscellaneous topics; all of this material has been omitted from the Collected Works except for three initial lists that attempt a classification of Shakespearean comedies and tragedies. Following these are 46 pages of notes for the Bampton Lectures that were turned into A Natural Perspective, numbered separately by Frye with the prefix “Sh.” Finally, fifty-six pages of notes for the Alexander Lectures, which became Fools of Time, are numbered with the prefix “Al.” The Bampton Lecture material (paragraphs 1–177) dates from 1963, as indicated by the list of projects in paragraph 4, prior to the delivery of the lectures in November 1963. Paragraphs 178–335 were composed prior to the delivery of the Alexander Lectures in March 1966. Braces throughout represent Frye’s brackets; these seem to have been added at a later point, most likely to indicate material incorporated, or to be incorporated, into the lectures. Roman numerals above many paragraphs were probably added later as well; they indicate the lecture (or chapter) to which the material belongs.

[1] |

Sea Comedies: CE,1 TN, MV, P, T |

Castle Tragedies: O, H, TC |

|---|---|---|

|

Forest Comedies: TGV, MND, AYL, |

Heath Tragedies: L, M, TAth |

|

Humor Comedies: LL, TS, MA |

|

|

TC: the walled Troy’s there P |

|

|

TAth: the heath Troy’s there Cy |

|

JC2 M H |

|

|

|

Co AC TC |

|

|

KL O TAth |

|

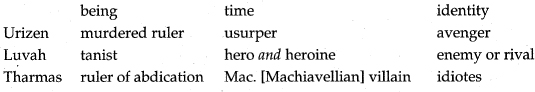

[3] |

sea3 CE TN MV P |

Ur. [Urizen] |

|

forest TG, MND, AYL, MW |

Luv. [Luvah] |

|

humor LL TS MA AW MM |

Th. [Tharmas] |

[4] 1963

Yeats Essay. Done

4 Milton Lectures

4 Shakespeare Lectures

Talk at the MLA. Done4

[5] The Bamptons Are About Shakespeare

[6] CE & the water imagery: drops falling into the sea. Apuleius imagery.5

[7] Red & white in the history plays: the malignant principle carried through Joan of Arc. PT & VA.

[8] I have decided, perhaps not permanently but certainly for the time being, to have the Bampton Lectures on Shakespeare. Reasons:

1) It gives me a specific topic, & my time is limited.

2) I don’t “possess” Shakespeare, but I do know him, & my papers about him have been fairly successful.

3) Biblical typology is out for this fall (no Hebrew); Romantic poetry is out; general theory is running pretty thin.

4) Shakespeare is the logical basis for 1 [Tragicomedy], as Milton is for L [Liberal].

5) A book on Shakespeare by me, if successful, would, appearing in 1964, make news & make money.6 The latter is the best motivation for academic writing ever discovered, as it creates exactly the right blend of detachment & concern.

[9] Now: the natural tendency, & a very healthy one, for critics of Shakespeare is to talk specifically about individual plays. But what I’d like to do is the kind of slopping-over job, on a huge scale, that I did (rather too much of for my own comfort: that was a prodigal & reckless paper) in my WT essay.7 The problem is this: Dante & Milton[,] because they are major poets, go straight to the archetypal centre of Western culture—in CH [Balzac’s Comèdie Humaine], of the human imagination. Shakespeare just writes one play after another; seems to have no archetypal interests whatever. There’s a strong Arnold-Eliot feeling that he’s a dangerous influence, & the reason for the feeling may be not just that his language is too clever but that he’s too empirically minded, & encourages our novelists & poets to think in terms of the random subject.

[10] What I’d like to do is study the inter-connecting imagery, ideas, characterizations & structural principles of the plays in such a way as to bring out the archetypal centre. The common-maker, as Priestley would call it.8 (This kind of irony is frequent in what Yeats would call my Body of Fate). If completely successful, it would be the best single volume on Shakespeare ever written.

[11] 10 autos (i.e. histories), 9 tragedies, 4 ironies (TC, T Ath, AW, MM), 10 comedies, 4 masques (i.e. romances). That’s five, & I seem to keep thinking of five—one extra for Denver, maybe. I suppose it would be logical to start with comedy & romance/simply because I know & like them best, but maybe the generic circle isn’t the best way to tackle this problem.

[12] Some of the stuff I’ve been collecting, apart from its own use for further theoretical work {incidentally, what I’ve got in the other notebook9 is really the germ of A [Anticlimax]: symposium, Utopia, metaphorical basis of thought & quizzical attitude to religion} would still be useful. The question of “play” itself, of course, & the structure as the impersonal centre vs. the direct message of content, may have something to do with Shakespeare’s extraordinary power of acceptance. His notions of patriotism, social hierarchy, & what constitutes a joke, are those of his audience: he seems to have no power of detachment—he may work through to it, but he sure as hell doesn’t start with it.

[13] What I should start with are the histories, the great double tetralogy using my H8 stuff as the epilogue. Or with the ironies: if I don’t insist on my paranoid canon-cracker notion I might do the series on four plays: (a) TC, MM, AW, TAth (b) TC, Lear, TAth, Cy* (c) TC, MND,10 Cy, R2.1 start with TC because of my notion that it starts a parallel series of British (H, L, M) & Roman (JC, AC, Co) plays (expanded to TAth by Plutarch) reconciled in Cy,11 which ought to turn up somewhere.

* This sequence particularly interests me: perhaps Cy might slop over into P, which is a rewritten version of CE.

[14] I.

The comedy paper might well open with my Iliad & Odyssey point.12 Actually I had better begin with comedy, simply because it’s easiest for me to see from there whether I can do my paranoid scheme or not. (Why the hell should it be paranoid? Surely there’s objective evidence by now that I do this sort of thing pretty well). The comedies take in all the romances & half the ironies, besides.

[15] II.

I should transfer my one idea about Jonson.13 One play that we know failed to please its audience was Jonson’s New Inn: we know this because its failure was so highly publicized by Jonson himself. There is something very disarming about Jonson’s attempts, as in The Magnetic Lady, to instruct his audience in the art of liking Ben Jonson,14 & in his determination to revenge himself, like Puff in Sheridan’s Critic, by saying “I’ll print it, every word.”15 But the arts of mousike are not the arts of techne.16 Parts that actors can get their teeth into are a product of wit, & wit is a product of rhythm & pacing. The characterization in The New Inn is by no means incompetent. But expertise in structure is a progressive unfolding of disguise, like unveiling a monument, & structure is a metaphor for the arts of techne. The fact that it’s rhythm & pacing that keeps a play on the boards, not structure, is the reason why an opera can survive by its music alone (Handel’s Rodelinde [Rodelinda]. In music, too, tremendous structural expertise may exist on the highest level (Bach) or on no level in particular (look up Raimondi).17

[16]

We should not overlook the anti-realism in Shakespeare: the deliberate anachronisms, for example. The historical hodge-podge that Samuel Johnson so despised in Cymbeline might have occurred to Shakespeare himself, & the image of “cannon” appears at the very opening of King John.18 It doesn’t do to say “Oh, well, the audience would never notice,” because many in the audience would notice, & feel that they had scored a point on Shakespeare by noticing. Besides, the assumption that Shakespeare was an impatient & slapdash writer is not a very fruitful one. It is a little truer to say, “Oh well, Shakespeare had more important things on his mind,” i.e. the imagery, though we shouldn’t assume that Shakespeare introduced the fine image of the thunderstorm because he “couldn’t resist” it. True, consistent imagery is more important than consistent historical fact. But we can’t ignore the element of deliberate departure from historical fact, a departure which stylizes the play, as departure from representational realism stylizes painting.

[17] I may be moving in the direction of a separable fifth theoretical paper, using stuff from the one I’ve begun. Then I could tackle the series of slop-over studies, TC, Lear, TAth, & Cy > P > CE. The reason I used the word paranoid is my audience’s conviction that there’s nothing new to be said on Shakespeare’s general conspectus as a poet, & that the only thing to do is duck inside one play at a time. I wonder if I could avoid this. I’ve thought for a long time of doing a paper on Lear: it isn’t a new notion. I can fan out from there into the conceptions of nature & nothingness, the storm as a reduction of creation to chaos, & so on.19

[18] That bit of horseplay I stole from Lister Sinclair20 is something I haven’t used since, though it’s true that the last time I did use it was in New York City. I mean the Titus Andronicus bit.

[19] {The World’s Best Garden: The Histories}

Nature & Nothingness: The Tragic & Ironic Plays

The Golden World: The Comedies

All of One Mind:21 The Romances

[20] III.

The Comedy of Errors is a trick done with mirrors: the twin theme means that, more or less, along with the tanist archetype.22 The Apuleian doppelganger fantasy is connected with imagery about drops of water falling into the sea, & the like, that have narcist overtones.23

[21] No: study the theme of the development of Shakespearean romance. Take romance as the telos or final cause of Shakespeare’s technique, & then pick out the elements in his earlier work that show that direction. This sounds gimmicky, but it doesn’t need to be. Take TC as a history play; follow it with the nature-nothing business in Lear, go on to Timon, then do the Comedy of Errors, which is earlier, but is an earlier version of Pericles:

I. Prelude & History (TC > Cy).

II. Nature & Nothing (L > WT).

III. Fool’s Gold (TAth >T).

IV. The Return from the Sea24 (CE > P).

Buggy, but the general idea will work.

[22] Shakespeare is close to the oral tradition; the search for a definitive written text is illusory and it’s easy to go out of proportion in thinking of verbal exactness as a basis for interpretation. TS, for example: it’s the overall structure that’s important, & that repeats.

[23] For IVI should read the sea group of comedies (CE, MV, TN, P & T) & link the imagery with Chaucer’s Franklin’s Tale, with the fishing business in Sakuntala & Rudens, with (of course) Apollonius in Gower, with Mucedorus & The Triumphs of Love & Fortune. Be thrifty: remember Bach.

[24] I starts off with my history point & TC as the fallen world, ending, as I say, with H8. All the histories come into it. Ill incorporates my Plutarch points and perhaps the Coriolanus stuff too. TAth is a play that shows the value of categorizing: so many take it as a failed tragedy, a King Lear that didn’t make it, whereas the kind of hero Timon is puts that comparison completely out of court.25 TAth is half folktale & half morality play. Incidentally, Shakespeare must have known that Apemantus means suffering no pain—I suppose he’s a student of Stoic apathy.26

[25] Some of that Harvard paper I never did use except in the Royal Society paper:27 I don’t think the Shakespeare surviving in opera business is in AC [Anatomy of Criticism]. Link with the Jonson point & my mythos-dianoia one: if you go after structure you may have rhythm, whereas if you go after rhythm you get the structure automatically.

[26] IV.

Patterns: King John’s hybris starts with his attempt to get rid of Arthur: the contrasting movement is when the Bastard defers to the child H3 [Henry III].28

IV (which may be moved back) should certainly turn on this Jonson business. One extreme is a static structure gradually revealed, a total disguise: that’s why SW [The Silent Woman] is Jonson’s best constructed play. The other extreme is the processional play. Pericles experiments with this, and Jonson was instinctively right in attacking it.29

[28] II.

Biblical archetypes are particularly important in seeing romance as Shakespeare’s telos, because they indicate the shape of his total myth. Jonah, Paul & Antiochus (Herod) turn up in Pericles. End of II, maybe.

[29] I.

The narrative basis of Pericles is a bit like Mozartian opera, the continuity being supplied by the equivalent of recitative:30 Gower’s prologues and the dumb shows. Curious the extremes of unity (Tempest, CE) and disunity (WT, Pericles). Derives from the history play, I suppose.

[30] IV.

Storm & tempest are the downward movement of the wheel of (fortune and) nature: the upward movement is {the rebirth of new life, in which art & Orpheus themes have a function. Statue becomes Hermione, “block” Thaisa, melancholy Pericles the restored king}.

[31] {Spatial mirror-trick of the twins in CE & TN becomes a temporal one with the risen Marina & Hermione-Perdita.}31

[32] IV.

In P.L. [Paradise Lost] the explicit imagery is Xn & Classical runs in cpt. [counterpoint] to it. In Comus this is reversed. So in Shakespeare: the Biblical articulation is subordinate to temples of Diana & such.

[33] The realism of the brothel scenes in Pericles was strong evidence to Victorian critics that Shakespeare did not write them and strong evidence to 20th c. critics that he did.32 The moral is that realism is a choice of conventions.

[34] II.

Something I haven’t yet got about the catharsis of comedy, as a structure independent of the moods of our responses. We may find TN serenely happy, or we may find it a dark comedy & Sir Toby a dismal shit & Malvolio a tragic hero. Our reactions are subsidiary to the structure, which makes such variety possible. There’s no definitive reaction, either to a single play or to Shakespeare as a whole. I’ll get this clearer after a bit.33

[35] Cymbeline with its denouement in 24 parts, is a Kunst der Fuge or academic play, a tour de force of recapitulation, like TN. It’s related to Othello somewhat as WT is related to Lear. Wonder if there is a Timon-Tempest affinity, as my scheme suggests: the romances are generally recapitulatory of Shakespeare, not just of the comedies: that’s my main point. In fact, though this kind of fearless symmetry is never much use, P has its centre of gravity, of recapitulation so to speak, in comedy, Cy in history, despite the Lucrece & Othello echoes, WT in tragedy, & T in irony (besides TAth, there’s the close MM link).

[36] II.?

In the history sequence the apocalyptic beginning & end are TC & Cy; the more strictly historical beginning & end are KJ & H8.1 think I could use my Hesperidean stuff here (prophecy at end of Friar Bungay & Peele’s Arraignment of Paris symb. [symbolism]) and I have my H8 notes. The prophecy of the birth of the (female) Elizabeth in H8 is an echo of the greater offstage birth in Cy.

[37] I.

Deliberate anachronism is one way of stylizing a play, to draw the spectator into a self-contained imgve. [imaginative] world, the retreat from realism in P marks an increase in “abstract” literary interest, as distortion does a pictorial interest. Another way is the use of deliberately unplausible folktale, especially in the problem comedies. Farce, less so. Also Stoll, in a perverse & bumbling way, got hold of a real point about Othello: the “big black fool” sermons from the audience are really protests against Shakespeare. Jonson uses different abstracting devices, mainly disguise, but his phrases about running away from & being afraid of Nature are accurate enough. We should get over the habit of speaking of such things as faults. If Cy has any merit, it has it because of its anachronisms, not in spite of them. They just might have occurred to Shakespeare, no matter how slapdash we may think he was.34 {The whole business of rescuing the realistic details is wrong—that’s why I say realism is a device of conventions}.35

[38] I.

The teleological play has unity of action, which means among other things that it keeps the action in a single plane, even if there are gods as well as men.36 The processional play is one of a group of types that expand the action into different dimensions. Two of these are important. {One is the reality > appearance dimension, of showing the play as a play & the play within a play is a species of this}. The manager’s prologue in Sakuntala; similar things in Pirandello. Mainly used for self-parody, as in Knight of the Burning Pestle. The Old Wives’ Tale is a beautiful example of this, & {presenting Pericles as a series of dramatized episodes from a Tale of Gower belongs to it. The big emblematic scenes in WT & T (masque) also belong}. The projected play, one might call it, EMOH [Every Man out of His Humour]: allegorical.

[39] I-II

The other is the play of vertical perspective, with scenes from heaven & hell. It’s common to connect tragic actions with hell, & {this is parodied in Jonson’s Devil Is an Ass}. The Prolog in Himmel [the Prologue in Heaven of Goethe’s Faust] goes back to the Book of Job. Peele’s Arraignment of Paris begins with Ate exploding from hell into a world of gods (mostly); The Rare Triumphs of Love & Fortune begins, Job-like, with Tisiphone coming from hell into the assembly of gods in heaven.37 This vertical perspective is preserved in the masque (and of course in operatic forms in a different way, where it raises the audience). The romances attempt to recapture some of this expanded perspective, what with the oracles & such.

[40] Further, all the stuff in the Harvard lecture of 1950 has not, so far as I remember, been used anywhere else, except in a paper buried in the RSG Transactions. Shakespeare & opera, the Whitman quotation, and soon.38

[41] II.

Further on the deliberately incredible: the explanations provided to the cast but not to the audience, and the curious, again almost deliberate, woodenness of the long expository scene in CE, which shows the disproportion between a romance story, which usually takes about twenty years to tell, and the dramatic presentation squeezed into a half day. It isn’t just inexperience, because exactly the same thing happens in T.39 Then in CE we note the rigidity of the irrational law set-up at the beginning, & the way it is deliberately ignored at the end. Similarly with the business of Shylock’s bond, the not a scruple more or less point [The Merchant of Venice, 4.2.326–32] is placed rightly for effect, wrongly for credibility. The defence of the unities of time & place assume that the audience can accept an illusion within limits. But in Shakespeare we are not being asked to accept an illusion: we are being asked to listen to the story. The manifesto of this simpler & more childlike appeal is set out once & for all in Peele’s Old Wives’ Tale, where Gammer Madge begins to tell her story to the young pages/Frolic & Fantastic. Q.40

[42] The Rare Triumphs of Love & Fortune (1582) has an opening scene in heaven, turning on a debat between Venus & Fortune. The former provides the happy ending & the latter the complications—pleasure & reality principles. In Shakespeare the symbol of Fortune is the tempest: the two are combined in Prospero. The magician is an agent of fortune, & the burning or destroying of his magic books signifies the end of the comic recognition. Symmetry in the wounding of brother & then of sister-heroine (latter a ritual death).

[43] I deals with the impetus of drama as against structure; II deals with the mythos as a displacement of myth. It looks from the present subtitle that my subconscious wants to deal with the four romances in order. “Mouldy Tales” is P; “Make Nature Afraid” seems to be settling into Cy; “The Triumph of Time,” though I was thinking of the historical TC-Cy sequence, is the subtitle of Pandosto, & “The Return from the Sea” certainly sounds like T.41 The other sequence is CE, TC, KL, TAth, which is chronologically right.

[44] II.

Curious the way Mediterranean & Atlantic worlds seem identified by superposition, like Albion & Jerusalem in Blake. The pastoral myth in England finally reached in Cy seems superimposed on Sicily. The scene of MA is laid in Sicily, where the Duke & his wife are Leonato & Innogen.42 The scene of T is between Carthage & Rome, yet the imagery is of Atlantic islands, mostly Bermuda. WT is Sicilian again, with those odd echoes of Lear.43

If you listen to a tale, instead of accepting an illusion, you trust the tale rather than the writer, as Lawrence said.44 {The sense of emancipation into a timeless world is the opposite of the teleological play, which is why a good romance always lasts at least fifteen years}. The expository scenes in CE & T set the atmosphere of a recounted tale, with charmed listeners: Gower’s function in P.

[46] II.

Jonson explicitly says that, like a realistic painter, he wants to be judged by his skill in rendering a subject-matter: Shakespeare depends for his persuasiveness not on logic, but exclusively on rhetoric. In the foreground are the speakers that fill up the emotional reactions to the mythical episodes; in the background is {the relentless “and then … and then” beat of the story}. If the rhetorical expression of the episodes is hasty or perfunctory (it is in RTLF [The Rare Triumphs of Love and Fortune]), the play seems crude: {the dramatist’s sense of timing must be infallible}.

[47] I’m still not sure why the romances are so rigidly conservative about society: why a poor girl can’t marry a prince without turning out to be a real princess. I suppose {the stability of society works against the wheel of fortune that keeps turning in 48}.45 It’s an auto appeal to subject oneself to the story, the opposite of hissing the villain in a melodrama. It’s so insistent and yet so damn silly, yet I found something similar as far away as Lady Murasaki. Aristocracy is a wish-fulfilment principle rather than a reality-principle. Anyway, {this is where the Whitman quotation goes}.46

[48] not used47 I.

The trial scene in MV stretches Shylock’s inflexibility to the absolute limit before Portia produces her drop of blood quibble, and then he drops the business about not one scruple more or less.48 The order may be wrong logically, but it’s right rhetorically, & that’s what matters.

[49] TragedyIII-IV

The deliberate anti-realism in Shakespeare is to take us into a self-contained dramatic imgve. [imaginative] world which eventually turns out to be a romance world. The temptation of Othello & Posthumus, morally & realistically, throws the onus on them: why the hell did they get jealous? Dramatically, it’s thrown on the villainy of Iago & Iachimo. This is clearer in Cy, where P [Posthumus] is practically exonerated from any wrongdoing at all. Cf. the Count in Figaro.

[50] Curious how thoroughgoing Shakespeare is in MM & {Cy} to touch every character with prospective death. {Like suspecting everybody in a detective story}.

[51] I.

So often we get the Elizabethan audience thrown at us as a kind of censor principle: what they would think. Hell, they weren’t allowed to think: not in Shakespeare. They could like or dislike the play, & that was it.49 When Jonson introduces Adam Overdo, the disguised magistrate, in BF [Bartholomew Fair], we are allowed to think that eavesdropping is not too sporting an event: we are not allowed to think this in MM. If we started to think about MM, we’d think that all the characters, with the possible exception of Lucio, were insane.50 This is a “problem” play, of the kind you think about from the start, but God what a mess it is when you start thinking about it that way. Take Ibsen’s Wild Duck as an example of a real problem play: three stages.

[52] IV.

All’s well that ends well is a rule of comedy: cf. the Book of Job, when Job gets three brand-new daughters at the end.51

[53] I.

Jonson takes the revenge of Puff in Sheridan’s Critic: “I’ll print it, every word.”52 Shakespeare doesn’t seem to have given a damn whether he ever got printed or not.

[54] What the hell is II about? About mythos & myth, of course, & either including, or leading up to, the imgve. [imaginative] vertical universe. The showing of death as a dramatic basanos53 is a moral dialectic separating the up from the down world.

[55] I said of Wyatt that not many poets got the resonance he could into the C of L [Court of Love] conventions. Shakespeare is a dramatist who gets the maximum of resonance out of them.

AW: Helena dies & revives, & is also {the presenter, accomplishing her two impossible tasks} of healing the old king & redeeming the young hero. The extraordinary melancholy of the play, from the opening scene all in black to the muted conclusion (Lafeu is disappointed) & that disconcerting speech of the “unhappy” & deeply religious clown, makes the title deliberately provocative. Shades of an underworld with a paternal or maternal figure surrounding Bertram.

[57] I-II.

There is no use assuming that in trying to interpret a play properly we are approximating Shakespeare’s view of it. So far as we know, he viewed his plays entirely in terms of their dramatic effectiveness.

[58] II.

{Shylock is a folklore Jew because he’s in a comedy; Othello is a black human being because he’s in a tragedy}.54 The empathy with the audience is closest in comedy.

[59] I.

Conventionalized literature is popular.

[60] IV.

II is the development through comedy to romance. The sea group; the forest group; the humor group. Note the persistent amnesia of comedy: my book of Job point.55 Unreality of what’s lived through; like dream, yet what’s lived through is what’s called reality. If I add TAth to the romances I should get IV clearer.

[61] III.

In both TN & AW we have an old clown hung over from an earlier generation, a somewhat bitter & melancholy clown. In both we have a melancholy & all-black opening scene, with Orsino & Olivia corresponding to the King of France & the Countess. Note how often the clown is a raping stallion: Feste, Lavache, Costard, Lancelot.

[62] IV.

I said in my essay on T that we start with a conception of reality as given & end with a conception of reality as created. The creating agent is “art,” which acts as illusion, in both T & WT. In P it’s music and healing (Cerimon). In AW at least the dispelling of illusion is the work of the disguised heroine. In AW Bertram thinks it’s heaven to screw Diana & hell to screw Helena, but in the dark he doesn’t know the difference.56

[63] III.

In EI [The Educated Imagination] I suggested that the white-goddess cycle was inside the Biblical one. In Shakespeare a black bride cycle fits inside the historical one. The white goddess one is dimly present in the tragedies, but the black bride or long-legged bait is what’s important.57 The long-legged bait is clearest in Marina of Pericles, where it’s linked with the magical invulnerability of chastity. Descent of Ishtar, not that that does me any good.

[64] III.

Parental figures are in the oracle scene in Cy as well as AW.

[65] IV.

The action of a manipulated or conventionalized comedy is often called providential: Ariosto’s Suppositi says God must have willed the conclusion, & a vicious parody of the same sentiment occurs in Machiavelli’s Mandragola, which I should quote.58 Hence the role of Diana, Jupiter & Apollo in Shakespeare, & the Christian-sounding transcendence of law in MM & MV & LLL.

[66] III.

Love disintegrates the comic society when it doesn’t crystallize it. This is the dramatic function of rivalry & jealousy.

[67] III.

TN begins, like AW, “all in black,” with Orsino melancholy & Olivia in mourning. Their cure, Sebastian to one & Viola to the other, is fished out of the sea. TN also calls attention to its improbability: the principle, of course, is that conventionalized plot is what’s relaxing.

[68] check for III.

I suppose Lyly’s Endymion is a pretty central type: hero an Adonis figure who prefers friendship to love (TGV, MA, the sonnets), & gets both. He is redeemed by the condescension of Cynthia, who turns out to be not a white goddess but an Isis figure. In Peele’s Arraignment of Paris Helen is an anti-Diana, declaring war on Diana in hell, forest & moon. The Hecate part of Diana is turned over to the C of L [Court of Love].

[69] |

Points of emotional repose: |

The Song |

|---|---|---|

|

The Soliloquy |

The Chorus Comment |

|

The Dumb Show |

|

|

The Emblematic Scene |

|

|

The Point of Ritual Death |

|

|

The Recognition |

|

|

The Final Dance, Wedding or Feast |

|

[70] II-III.

II should begin with structure as the focus of eye vs. kinetic emotion (Dryden)59 as the focus of a mob. TS: ironic double moment of K [Katharina] & B [Bianca]. In Sh’s [Shakespeare’s] play Sly goes to sleep after the 1st scene, which is right. In the Q [Quarto] he reappears at the end, having had the play as a wet dream, ready to apply its principles to his own married life.60

[71] I.

In writing on T.S. Eliot61 I came to realize that his theory of poetic drama really applied best of all to The Waste Land, & that his actual plays moved steadily away from it. His movement is the opposite of Shakespeare, who goes from action-controlled plays to the operatic Pericles, where Gower tells the story in recitativo & a series of scenes literally supported by melos & opsis (dumb show) which epiphanizes the story.

[72] Well, I ought to be fairly clear by now, II seems to be essentially an analysis of the structure of comedy, as I have it now, going through the features that point to romance. Ill brings up the world-picture & the history sequence from TC to Cy. The apocalyptic imagery in A&C & why it’s there: the whole static picture of time, nature, fortune, and art. IV would then try to set this in motion by discussing the essential point of history (liberalizing continuity), comedy (regeneration of nature by art), & of tragedy (vision of original destiny of hero). Perhaps it’s in IV rather than II that I deal with my Co–T Ath–P sequence, the scaling down of human perspective, & the like, but my H8 points surely belong in III.

[73] In Sakuntala62 a king loves a displaced tree-maiden (she has a bark dress & is beloved by the wood nymphs), the child of a sage & a nymph sent to tempt him. She unintentionally offends another sage63 who curses her, causes the king to forget that he married her secretly—she’s pregnant. The cursing sage later modifies his curse to saying it’ll end when the king sees “the ring of recognition” he’s given S. S. loses the ring: it falls into the Ganges & is swallowed by a carp which is caught by a fisherman who is arrested for stealing the ring. The king then remembers, but S. in the meantime has been caught up to heaven, or at least a Lower Paradise. The king is led there by Indra’s charioteer, where he meets his child (prophecy of the child’s greatness as the later King Bharata is the main point) &, eventually, S. The general shape of the action is closest to AW.

[74] II.

When the dromenon64 is cut off the magic turns inward & helps build up the imgve. [imaginative] universe. The theme of the abandoning of magic is linked to the completing of the comic action.

[75] III-IV.

II is a study of comedy as, in origin, a magical inducing of a birth; thence, as literature, a drive toward identity. This identity has social (new society), individual (released humor), natural (solstitial pointing & green world), divine (providence) aspects, all interrelated & harmonized by “art.”

[76] II, etc.

III is a study of Shakespearean imagery founded on the assumption that the “Elizabethan world-picture” is not just a matter of humors & planetary spheres. It starts with the expansion of history into the TC-Cy sequence, then fits that into the Biblical sequence by way of the apocalyptic symbolism in AC [Antony and Cleopatra]. It develops the musictempest imagery out of II & the contrast of love & fortune. Also the grotesqueries in the comedies (Falstaff as whale; cook in CE as Great Whore) take their humor from their resonance within the dramatic universe.65

[77] IV is probably a study of the sequence of Shakespeare’s later plays up to the romances. How far back I’ll go I don’t know, but I should think the L-M-AC-Co-TAth sequence, along with some discussion of AW & MM, should be there anyway.

[78] III.

The comedies begin in the shadow of death or melancholy, followed by a period of confusion symbolized by either wandering or by disguise, or both. Disguise, almost always a girl dressing as a boy, is a development of a ritual of interchanging garments in a period of saturnalia. My Deut. [Deuteronomy] point. The theme of lust in MM & P is part of the license theme.

[79] II.

Note that my two themes, the cutting off of the externally related dromenon66 and the structure as the focus of a community, are closely related to Dryden’s notions of the power of music as magical in a preartistic way.67

[80] Tragedy III (II)

One of the main points of IV is the study of the pharmakos figure: my Coriolanus point developing through Alcibiades in Timon (return for vengeance reconciled) & Belarius in Cy. Antony in AC is one because he’s a triple pillar of the world, Lepidus is called this in mockery: Antony really is a soldier’s (may)pole reaching to the moon, an Atlas or Babel figure: Octavius wins because he is never (check) so regarded or referred to: he can survive a tragedy because he adjusts to a fallen world, like Ulysses in TC.

[81] II.

The people who engage in magical rituals are agents: they’d probably resent the suggestion that they are actors in a play, which is how they look to a “critic,” such as an anthropologist. As soon as they turn inward, myth takes charge of dromenon.68 But {myth then needs to be displaced in the direction of a historical event, or, later, a romantic story, for the myth can’t just be: this is a contest of summer & winter”; the absurdity of that deprived of magic is too manifest}.69

[82] III.

I don’t know if I could arrive at a theory of the typical structure of comedy in II: I can generalize three stages: an opening scene which sets up either an absurd law (social: CE, MND, MM) or a melancholy mood (individual: TN, MV, AW); second, a period of wandering & disguise where values are upset; third, the comic stretto.70 This corresponds to Gaster’s periods of fasting, purgation & festival.71 {Note the similarity of the Isis bride of the Song of Songs seeking the groom & the disguised heroine seeking her man.} Now if I could divide the stretto into typical agon-pathos-anagnorisis phases I’d be all set, but that’s too easy. There’s a strong agon theme in MV, in the typical form of the lawsuit. Pharmakos figures include Falstaff in MW (from the very opening line), Parolles, whose unmasking is a relief because it leads him to a sense of identity, & Malvolio. But I doubt if anything as clear-cut as Aristophanes’ form would emerge.

[83] IV.

In Sakuntala the denouement occurs when the king is told that his forgetfulness of the heroine wasn’t his fault. Bunyan in the Valley of the Shadow—I mean Christian—is distressed by the evil voices he hears, because he thought they came [sic] from his own mind. This is connected with the dramatic tendency to make a pharmakos of the tempter and absolve the temptee. You can’t do it with Bertram, but it’s done with Claudio: one’s the other inside out.

[84] IV.

Wonder why drama & romance always aim straight for marriage, which means a black bride cycle, and why lyric poetry is so largely confined to the white goddess.

[85] III.

Anyway, Gaster’s kenosis-plerosis scheme72 is clear in WT & perhaps in P, not impossibly in MM, which seems to have the same binary form as WT.

[86] {Oaths, compacts & laws relate to the social side of comedy; witnesses are chorus characters and pharmakoi like Jaques in AY; the ordeal is individual} (except in that extraordinary Lope de Vega play).73

[87] Gaster quotes Bourne as saying that Midsummer fires were kindled in order that “the lustful Dragons might be driven away,” his note referring to Brand’s P.A., 304. MW?74

[88] I might use my PT point as an example of what I mean by identification.75

[89] IV.

The conflict with the dragon of the sea is reflected in the sea comedies, especially T. The shipwrecked group is the sea, human life unredeemed. The sea encounter, music against tempest, is dialectic (P & T); the green world group are more cyclical.

[90] IV.

I’ve said this in a different way, but {emancipation from law in comedy has to do with internalizing behavior: the hero really disappears into the audience who identify with him}. So does the tragic hero, but he draws the audience together: the comic hero individualizes it. In this process everything “out there,” everything fixed or definable or compulsory, becomes a subordinate reality. The individualized audience is partly the reason for the contrasting assembly at the end of a comedy.

[91] III.

I suppose Herne is an Anglicized Orion, a lubberly hunter.76 The MW seems, with its red, white & green in Q [the Quarto], is [sic] the one obvious example of Shakespeare’s use of folklore ritual drama.

[92] III.

The N.C. [New Comedy] scheme of the triumph of youth over the senex iratus is all right as far as it goes, but I shouldn’t overlook the fact that one of the central elements in the comic resolution is continuity. The pharmakos has to be very carefully handled: either he’s voluntary, like Jaques, or reconciled, like Malvolio. Emphasis on driving him out tends to make the society a mob.77 Anyway (I’ve said all this) the senex is never a pharmakos: he’s always reconciled, because {only continuity can liberate. That’s one reason why the romances are so insanely conservative.}

[93] III.

In Shakespeare lust, a generalized desire for a female, is a sterility principle, opposed to love. This is clear in Pericles, and in MW, where the lustful {Falstaff is identified with Herne the hunter, a sterility principle}. Similarly Bertram & Angelo think it’s heaven to go to bed with Diana or Isabella & hell to go to bed with Helena or Mariana, but in the dark they can’t tell the difference.78 ([Terence’s] Hecyra theme of previous salvation: Ion of course).

[94] III.

In TGV we have the purest C of L [Court of Love] in Shakespeare: {Silvia is called lady} & calls her lovers servants. Hence this theme runs through its logical course to renunciation in favor of friendship, which is right for the convention but wrong for drama, which is entirely black-bride. The C of L is another sterility principle that has to be cast out.

[95] III.

The theme of the expulsion of lust in MM: {Angelo’s private virtue is relevant magically: you can’t set vice to catch vice in a fairytale. Lucio’s punishment in making him marry a whore is in direct cpt. [counterpoint] to Angelo’s being forced to marry Mariana.}

[96] Tragedy? II?

My Shakespeare and Milton studies are drawing closer together:79 the disappearance of a central character transforms the action from external spectacle into the internal identity of the final society. The king disappears in H41 (many marching in his coats), in H5 (Harry le Roy) and of course in MM (the duke as principle of government).

[97] Well, I & II are now pretty clear, & III is manifesting an outline or two. IV is still a fairly complete haze, unless it’s the present III.

[98] IV.

Quote the passage from the preface to the Q [Quarto] of TC about the comedies having sprung from the sea of Venus.80 In T the masque of gods has a deliberate auto form—the recession of the flood.

[99] III.

Re the pharmakos principle: what is expelled is either a person or a state of mind. The nearer melodrama & kinetic mob feeling a comedy is, the more the pharmakos is a person: in a civilized comedy it’s a state like lust, & the individual is reclaimed, or married off beyond his merits, like Claudio or Proteus. (Grace vs. merit). The voluntary pharmakos Jaques is an interesting experiment: half comic butt & half chorus. His religious leanings link him with Lavache in AW, & Lavache has links both with Feste & with Armado—this last again is part butt & part chorus. Melancholy, real or affected, is the anti-comic humor.

[100] III.

Identity in marriage (PT) is expressed by the very accurate phrasing of the Hymen song in AY: “atone together.”81 {This song also expands the perspective in assimilating the forest of Arden to “heaven”—the Sakuntala recognition scene}.

[101] The sequence II-IV is the same as the Milton I-III82—structure, imagery, characterization. If I got the world-picture expanded into III, I think IV should open out all right.

[102] II.

(Rewritten earlier point). Love depends on grace, not on merit. It is curious how many men are married to great applause [to someone] whom one would think no great catch: Bertram, Angelo, Claudio, Demetrius, Proteus, even Sir Toby. Several things here: the drive to a festive conclusion (all’s well); the sense of previous events as forgotten, etc. After all, in reading detective stories we often feel that most people who get murdered deserve it, & sympathize with the murderer.

[103] II.

In [Terence’s] Hecyra all the characters including the courtesan Bacchis are decent & kindly people except the hero Pamphilus. He’s a jerk: the most troublesome juvenile delinquent in New York would have a more intelligible code of morals than that83. Similarly with Claudio, who makes no resistance whatever to the suggestion that Hero is unfaithful: merely says that if she is of course he’ll repudiate her. Afterwards he shows not the slightest sign of remorse or even awareness of other views, until he’s proved wrong. Beatrice has the sympathy of the audience when she regards him as a worm, but the amnesia of the action carries him along.84 I think the point of MA is, besides its title, the double action: Claudio doesn’t need to be released from a humor because Benedick is.

[104] IV.

The amnesia drive means that, as in Sakuntala, the resolution is in a different world. TS is, in the Q [Quarto], projected as a dream of Sly.

[105] The main theme of II-IV, and perhaps the specific theme of IV, is the principle that the greater the writer the more central the principles he recaptures. Hence Shakespeare starts out with N.C. [New Comedy] & Seneca & a few Italian & early English models, & promptly feels his way back through Menander & Euripides to the original ritual pattern. I suppose my Sakuntala summary would then go into IV.

[106] Literature exists in the unborn world85 between is and is not. In tragedy we are oppressed by the feeling of reality or is, & have to remind ourselves (e.g. in the blinding of Gloucester) that we can be entertained & feel exuberant because it’s not happening. In comedy we are oppressed by the feeling of unreality or is not, & this survives in the sense of amnesia. We say to the Gloucester scene: “This, thank God, isn’t happening, but it’s the kind of thing that could happen.” To the fifth act of AY we say: “This is the kind of thing that couldn’t happen, but it’s happening.” We remind ourselves of the reality of our desire to see things turn out “right,” and of the strength of the impetus toward such a conclusion: that’s the reality of comedy.

[107] II.

Re the cutting off of the dromenon:86 drama is born in the renunciation of magic, & at the end of T it remembers its inheritance. Its external relations, like Prospero’s after his exile, are with a purely human world, & so become psychological, a quest for identity.

[108] Tragedy? III-IV

In our cultural framework the yearly cycle (& daily) is projected as fall & apocalypse, & I think I can find enough in Shakespeare to show that those Biblical archetypes, usually in their Ovidian form, appear in him. But the real fall is the awakening of a self-conscious individual in an alien world, & the real apocalypse his further awakening in a society that corresponds to & complements his individuality, & Shakespeare’s structures might be interpreted as ways of expressing the Biblical structure without being tied down to explicit Biblical symbols. If I could show that, III at least would be clear.

[109] IV.

When drama renounces magic it enters a purely human world. Its external relations are with ordinary human life; when it turns its back on life and forms a self-contained literary universe it seeks enclosed reality, nature which is art, cf. Polixenes.

[110] Tragedy? not used: some III & some IV

Re that Timon-T link that’s been bugging me: I want IV to deal partly with the theme of the isolated figure, to which the rhetoricless Coriolanus & Timon are linked. Timon is a sacrificial man eaten & drunk in the first half & tries to identify himself with the tempest arch, [archetype] in the 2nd half. The tempest in Shakespeare (Lear, WT, etc.) is the destruction of the order of nature, not just bad weather. Now Prospero is an isolated pharmakos in the first half of the action (i.e. before the play begins), & begins his communal-man role with a tempest.

[111] IV.

Cf. Proteus’s remark in TGV about Orpheus’s compelling Leviathan to dance on sands with H5’s remark at Harfleur that the kind of king he is can’t.87

[112] III.

The fool in the comedies is often the character who remains individualized, outside the new identity.88 In TN he’s lustful & a hangover from a previous generation—both recurring themes. He makes his speech about the whirligig of time [5.1.376–7] when Olivia uses the word “fool” to Malvolio the churl, yet he’s still isolated as his plaintive song at the end shows. Jaques is the educated fool or satirist, who feels an immediate sense of identity with Touchstone & shows a curious jealousy of his marriage. He’s a wanderer, a perpetual spectator. Lavache in AW is again lustful & of the previous generation, & he makes that terrifying speech.89 Falstaff in MW & his fairies speech [5.5.122–8]. Armado in LL, which reverses all the imagery of comedy, brings off all the honours. In the romances the fool tends to become the natural man: Cloten is different in Cy; Autolycus in WT has much of the role but is a thief; Trinculo, note, is the object of Caliban’s jealousy, & is a jester. Cf. the “motley to the view” sonnet [Sonnet 110]. There is a curious conversation between Lavache & Parolles which also establishes a link: Parolles achieves his identity by being known for a fool.

[113] III.

This business of the fool’s double90 is interesting: examples are: Armado-Costard (LL); Touchstone-Jaques (AY); Caliban-Trinculo (T); Lavache-Parolles (AW); perhaps Lucio-Pompey (MM); certainly Feste-Malvolio (TN). It may be part of the general doubling theme. Gobbo-Shylock (MV); undeveloped but anticipates the escape-from-Shylock theme. Jaques is inspired by Touchstone to become a satirist, a role he attempts with Orlando without much success. He’s a Childe Harold but not a Byron.

[114] III.

The real fall of man is not a historical event but the awakening of self-consciousness in the individual, the kind of awareness that alienates. The alien consciousness eats into the belief in sympathetic magic & so helps to create drama; but it’s essentially the attitude of the spectator. Hence a dialectic is created between the attitude of the spectator as such and the aspect of him that participates in the comic apocalypse, the society created around and as one man.

[115] III.

MW relates to the forest comedies partly because, as in AY & TG, there’s a sense of an original Golden Age Robin Hood group, to which Prince Henry & Fenton belonged. MW describes first the degenerate Falstaff society, then the isolation of Falstaff when he discharges his followers, then a hint of a rebirth when Fenton does what Falstaff can’t do, invade the middle-class Windsor society. The Falstaff groups are brigands or drones until they disperse, & then Falstaff goes into his carrying-out-Death role.

[116] Coriolanus is an ironic Alcibiades—it’s in the TC conception. A crude, heroic warrior aristocracy looked at in terms of its actual relation to a debased mob—debased because the aristocracy is there.

[117] III.

The internalization of parental figures: the Cy oracle, AW, T. {The failure to internalize is the tragedy of Co.} It’s a central part of the identity problem. An identified person is identified with his wife and as his reborn ancestry. The opposite is fortune, separating the lovers, and law, the sense of parental authority externally imposed.

[118] IV.

In the histories, which are closely related to the tragedies, continuity is established by force: Octavius, Fortinbras, Macduff—but there’s no internalizing of it as there is in comedy, hence the rejection of H5’s comic father Falstaff. No internalizing of the natural or Belarius society.

[119] III.

The period of sexual license is usually, as I say, represented by the heroine’s disguise as a boy.91 The “problem” comedies use the substituted bride, & MND has a similar device. TG has the disguise plus Proteus’ fickleness: confusion of identity in CE & TN is nearer the centre. The 6 times are TG, MV, AY, MW, TN and Cy.

[120] IV.

In the Renaissance a good deal of the conception “natural” was simply what one was used to. Thus Sidney is horrified by the barbarous practice of putting rings in the nose instead of “in the fit & natural places of the ears.”92

[121] III. & IV.

The disguise93 of the heroine can be a death as well—loathly lady94 arch, [archetype]. “One Hero died defiled, but I do live,” says Hero in MA [5.4.63]. I still don’t know what MA is about, but there’s a great deal of insistence on Hero’s death. Borachio’s drunken talk about the giddiness of fashion is repeated in an odd way by Benedick.

[122] IV.

The newness of the new society may be the old renewed, but it is never a return to the old. The return to the old is the nostalgic, which is not the comic. The instinct to retreat to a child’s protected society is the root of the conception of the sentimental, which is something Shakespearean comedies at their worst never are.95 The amnesia point is connected with this.

[123] III. or IV.

At present I think of IV as essentially a study of the four romances, using Co & TAth as a prelude & H8 as a postlude. That would make it difficult to summarize. I need more stuff on the continuity of history, the legitimacy principle as the real comic death-&-renewal pattern in history which is continually interrupted by usurpation & tyranny (fortune). Shakespeare has no opinions—only structural patterns. My RJ note will be useful, also some of my H6 marginalia. My thoughts seem to be running on the relation of comedy & history, with relatively little on tragedy. The historical ideal is the weeded garden of R2: the Lancastrians split this into the two father-figures H4 & Falstaff, so that H5 has to choose one & not the other. The Roman world is similarly split between Octavius—or Octavia—and Cleopatra.

[124] IV.

Other splits: Hector-Ulysses; Timon-Alcibiades; Prospero-Antonio. Perhaps that’s the role of Belarius too. Cymbeline: Wales seems to have a secret-garden role in that play: perhaps an Arthur-Tudor allegory.

[125] Tragedy II.

Critics of Shakespeare may amuse themselves by discussing whether or not Romeo was damned: there is no evidence that Shakespeare did.96

[126] IV.

The theme of madness in the comedies: “This is very midsummer madness,” Olivia says of Malvolio [Twelfth Night, 3.4.56], and the same common phrase may be responsible for the title of MND, the action of which appears to take place on the first of May.

[127] The obvious accentuating of a story by a conventional pattern such as the whodunit of a detective story is what makes highly conventional literature so readable. It also makes the quality of description & characterization in the writing a rhetorical tour de force, something achieved in spite of the convention.97 {Shakespeare is attracted to history at first because the events of the chronicles indicate the framework that he has to fill up with the appropriate rhetoric}.

[128] not used: Tragedy II.98

H61: Talbot is the tragic hero, of course, the survival of the H5 spirit, conquerable only, like Coriolanus, by treachery. He compares himself & his son to Daedalus & Icarus, who escape by death from what Suffolk later calls a labyrinth full of Minotaurs.99 The end of the play mentions Paris & Helen, the theme being the transfer of the demonic female will from a foreign enemy (Joan) to England itself (Margaret): evil is internalized at the moment it’s caught. Same sort of design as the coronation of H6 in Act IV accompanied by the chasing out of the pharmakos Fastolfe. The poignant scene of the death of Mortimer indicates the dimension of the ancestral curse on the House of Lancaster, without compelling us to accept it. Joan is so complex a character that critics assign her to two authors, the one they approve of being Shakespeare. She speaks well & nobly of her mission, of France’s case (her rhetoric is supposed to hypnotize Burgundy at once), and seems genuinely possessed by a belief in her own purity & nobility of descent. At the same time she has a brusque realism (v. [viz] the titles of Talbot); she speaks well for France just as Shylock speaks well for Jews. Yet she’s terrified of death. To have unified these elements into a rhetorically convincing unit would have been a formidable task for Shakespeare at the height of his powers, & of course would have completely shattered a mere chronicle play. As with Shylock or Cleopatra, she’s isolated from the action, yet one feels that a separate dramatic world, where France has its de jure kingship, is locked up inside her. She may have turned to fiends in a genuine patriotism, & so be less ruthless than Lady Macbeth. We can’t say, because she’s not natural; but it’s all potentially there. The hypothesis is purely dramatic: let England’s enemy be evil and treacherous (using unfair weapons). No actress could bring unity out of Joan’s character, for the interconnecting links have not been written.

[129] IV.

I’m still not clear about the independence of dramatic structure from how we feel about the characters, but it seems to be shaping up as the central principle of IV. The Hecyra point.100 The question “Is Falstaff a coward?” is a good example of a pseudo-problem in criticism. Falstaff appears in plays that are dominated by acceptance of a heroic code, & he doesn’t accept it, playing the role in history of a churl in comedy. Whether or not this makes him a coward depends on our moral attitude to that code. Fastolfe, in H61, is presented as a simple coward within the assumptions of the heroic convention of the play, where Talbot is a tragic hero. Falstaff is not simple, because he’s able to articulate other standards such as realistic common sense.

[130] not used: perhaps Tragedy? III?

We deal with such confusers of assumptions as though they were real people ([Samuel] Johnson & [Elmer Edgar] Stoll no less than [Frances] Ferguson & [A.C.] Bradley) because they set up a direct rapprochement with the audience. In the H6-R3 tetralogy it isn’t until R3 emerges from the final play that we feel real dramatic integrity of character standing out from the tapestry. The reason is that he’s an actor, and a hypocrite or masked character, and he suggests a kind of real life, however reprehensible, which he & the audience at least know about.

[131] II.

It’s unnecessary to assume that Shakespeare accepted his conventions, and very dangerous to assume that he accepted ours and treated his own audience ironically. We have tough & tender-minded critics taking one side or other of these views, equally irrelevant.

[132] I’m beginning to suspect that III & IV have to interchange, & that what I end with is the typological panorama & the general view of imagery. This would include Shakespeare’s total view of history, which incorporates the more dialectical view of tragedy & comedy. H6-R3 is a cycle ending in the dialectical precipitates of H7 [Henry VII] & R3 [Richard III].

[133] cf. Tragedy not used:101 III could use Joan & other history e.g.’s. Isolation from the action: in all the dreary Wars of the Roses we feel dramatic sympathy primarily with the losers, because they’re isolated from the action. It looks as though III were primarily a study of this feature of isolation, taking off from the fool-pharmakos situation in the comedies. In the histories, the fool role becomes tragic & heroic, the role of John of Gaunt in R2, of Talbot in H61, of Humphrey in H62, of H6 himself in H63, of (perhaps) Clarence in R3, and of Falstaff in H5.

[134] Tragedy I-II.

R2 is isolated in the opposite way from R3. The latter is pure de facto & hypocrite; R2 is pure de jure, & is an actor who throws himself into every role suggested to him, notably that of the betrayed Christ. Shakespeare plays down his twenty years of incompetence & concentrates everything on the pathos of deposition. Why? Was he superstitious about the magic of de jure royalty? I doubt it. He’s the already fallen & doomed son of Adam (Abel).

[135] III.

I don’t seem to have said that a) TAth is a comedy turned inside out, disappearing into the mind of a pharmakos character, much as T turns MM inside out b) the quarrel of Timon & Apemantus102 (a fool) is the stretto of the comic fool-pharmakos tension. Qy [Query]: does Thersites represent the amalgamating of fool & pharmakos in the same person?

Independence of dramatic structure has something to do with the integrity of the contrasting world inside the pharmakos’ mind. TN from Malvolio’s point of view is a pretty grim play.103 Leave this out, & we have melodrama; make too much of it, & we have sentimentalized rcsm. [romanticism]. We can never get the perfect performance, of course:104 every performance has to select what it will do.

[137] IV.

The sentimental nostalgia, directed at the individual childhood: the song of innocence, the vision of Beulah, the recognition of Shakespearean romance comes very close to the sentimental but avoids it because it’s directed toward the generic or Adamic childhood.105 In romance there’s a stronger sense of re-establishing something forgotten than in the festive comedies, which stress rather resolution than recognition.

[138] II if anywhere not used & probably not usable now.

The point I now have at the end of I should be developed in IV: pick up again the Portrait discussion of lyric-epic-drama progression,106 and show that it’s a distinction among personal-centered, like-centered & individual-centered (in Jung’s sense) artists, not a generic distinction. Joyce is fascinated by it because the problem of casting adrift from the ego-centered consciousness is the crux of his art. Shakespeare seems never to have had an ego-center: in any case we can’t point to it or locate it. I want IV to try to outline what his omniscient and epiphanic vision is, through his imagery-structure.

[139] mostly IV, I think

The other world exists in Shakespeare, as in Dante, mainly to confirm the social set-up in this one. Jack Cade, according to Iden, goes to hell; Edward IV goes to heaven. Hubert is “damned” if he kills the rightful heir Arthur, yet H4 seems to get away with dodging the responsibility for killing R2. This principle of presenting a wish-fulfilment world as aristocratic is in the romances. It’s a bugger to try to understand a writer who has no personal attitude. The king de jure has a magical aura around him: the logic of such a superstition is that a king de facto who has any claim to the throne at all should exterminate everybody with a better one, & will thereby acquire that aura. R3 thinks he’s done it; this is why I call the principle of legitimacy comic: {the hidden eiron gimmick we’ve forgotten about}.107

{The principle of legitimacy comes into the Christian myth too: the gospels begin by demonstrating Jesus’ descent from David. Macbeth is Herod: he slaughters all the innocents within reach.}108 The Herod background to A&C is important too. The Roman plays have no principle of legitimacy: that’s one reason why our sympathies are so divided. They repeat the TC fall world. The legitimacy principle, as H8 indicates, indicates109 the providential at work in history.

[141] II.

Macbeth is the most concentrated study of tyranny as a force within the individual soul which has to be cast out of that as well as out of society. The tyrant exists because his victims are tyrants to themselves. Hence the otherwise tedious & embarrassing business of Malcolm’s confession to Macduff. Nota bene, for I, that Macbeth is not a play about the moral crime of murder: it is a play about the dramatically conventional crime of killing the lawful king.

[142] II.

Jonson has an armed prologue in the Poetaster to make a comment on society; Shakespeare has one in TC for decorum, as a symbol belonging to the theme.110

[143] IV.

In the Roman plays there’s no principle of legitimacy, but {in AC & Cy there’s an offstage Christ child as a hidden eiron gimmick}. Analogues of it elsewhere too: {Macbeth is a Herod or Pharaoh, & Antiochus is in P}. The tribute to Rome in Cy has also the legitimist comic overtone of the third Troy subjecting itself to the second one.

[144] IV (mostly) Tragedy I

The Roman perspective is ironic: our sympathies divide, & the relevant example is the destruction of Troy in TC. The other principle is romantic, where there is a correlation in “virtue” or “nobility” or “gentleness” between moral & social rank (“I am the best of them that speak this speech” [The Tempest, 1.2.430]).

[145] written but so far excreted.

IV may begin with the Joyce argument [see par. 138]. Lyric poets have a centre in themselves, which may be extracted by looking at the characteristic images. Epic poets articulate the centre. Dramatic poets have an epiphanic or movable centre, revealed in every play they write.

[146] III.

At the end of a comedy part of us is engaged in the wedding festivity, but part of us is outside, hypnotized by a lank figure with a wild tale about a becalmed & God-forsaken ship.111

[147] III.

{In Courtly Love poetry the act of falling in love & under the rule of the God of Love is analogous to accepting the social contract} in philosophy. In comedy the contract appears at the end. No it doesn’t.

[148] Continuity as a liberalizing principle (Burke)112 is the point of the histories. The fact that art aids in restoring this is the point of the comedies. Epiphany in law of an original heroic vision is the point of the tragedies.

[149] {The fact that disguise is conventionally impenetrable to other characters, though never to us, reinforces the amnesia feeling of double focus.} Similarly with the identical twins in CE & TN & the lovers-in-the-dark of MND.

[150] Conclusion of II ought to make something of the catharis of comedy.113 We raise sympathy & ridicule in order to cast them out: this principle gets into the society-spectator dialectic of III & the catharis of comedy concludes III.

[151] IV begins by saying that the action of comedy is a social construct, & hence it enters the order of nature. That leads into the conception of nature in Shakespeare. The man who doesn’t enter the contract is under the law (Shylock) or a noble savage (Caliban) or a melancholy wanderer (Jaques).

[152] Tragedy!

I must have this somewhere else [par. 148]: Shakespeare’s histories are intensely conservative, in the Burke sense, with legitimacy & continuity being not merely a steadying but a liberalizing & emancipating force. The revolutionary side of him is in the comedies, where it’s the Los creative revolution through art & not the Ore one.

[153] In your discussion of spectator figures, don’t forget the role of Christopher Sly as a spectator of TS, with his illusionary dream-bride, a boy in disguise like the brides of Slender & Caius.

[154] In comedy the primitive basis is of continuity of life. Falstaff is the greatest comic figure in Shakespeare, & this has much to do with his unquenchable will to live. Parolles in a shrunken form. Hence reconciliation, removal of fear of death (MM) & Prospero’s responsibility for Caliban.

[155] {MW: Ford cured of jealousy (individual), Falstaff of “sinful fantasy” (dual-erotic), Page of trying to marry his daughter to a wealthy fool (social).}

[156] not used: rep. Tragedy III

I’ve said [par. 130] that R3 is the first character in the H6 tetralogy to emerge from the historical tapestry as a human being. We don’t like him morally, but we like him dramatically: a sardonic wink to the audience114 puts him in a different class from the other characters. He knows he’s an actor. I don’t mean a stage actor: I mean a hypocrite in its full sense. The others all take life too seriously: they’re too preoccupied with turning the wheel of fortune (at the mill with slaves) to look up at us. Richard’s sense of illusion is what makes him real to us.

[157] Heroism as death & revival incarnates the nation: this is true even of R [Richard] whose [?] dies & is reborn as an aggressive submissiveness.

[158] IV.

Connect the garden image in R2 with Prospero’s “trash for overtopping” [The Tempest, 1.2.81] images: the cultivated state of art which is human natural society. Not Eden,115 but under it; not the Ararat world of the T masque either. History theme of coronation-with-pharmakos is underneath the green world: elusive Orpheus in H8.

[159] Patching: the sentimental is the individual equivalent of mob reaction, false introversion as the other is false extraversion.*

The interchange of reality & illusion, without moralizing, creates a moral dialectic.

* opposite of true introversion (self-knowledge and the spectral) & true extroversion (pragmatic society and participation),

[160] Patching:

I, i: middle distance perspective.

IV: reality > appearance dialectic (e.g. MV) as part of the conclusion of IV.

I: the ballad disjointing of narrative (Sir Patrick Spens).116 Possible link with the spectator dialectic;

Apuleius world of CE: even the ass transformation is there;

primitive fear of the doppelganger & theme of self-knowledge.

[161] You’ve got P featured in I: could you feature Cy in II a bit more? The songs of clown & death assoc. w. Imogen, for instance.

T seems to fit III & WTIV, though the final [?].117

[162] TS provoked rejoinders but they’re contained in Bianca.118

[163] Primitive fear of loss of identity (Jekyll-Hyde) relieved by meeting identical (i.e. very similar) twins. CE

[164] III: retitle: cf P: “played upon before your time” [Pericles, 1.1.84].

[165] Curious reversal of the roles of Ariel & Caliban: it seems to be Ariel who’s so full of energy & Caliban who wants to dissolve back into the elements, but the opposite is what’s true.

[166] Invariable theme of the harsh father in the four romances: Antiochus, Cymbeline, Leontes, Prospero.

[167] In my Argument of Comedy paper I made a flip remark about there being no second world in the problem comedies.119 In AW the second world is Helena with her father’s secret, the germ of the natural society of the romances (she can restore to health). Collision with artificial society of court: Bertram has the role of hostile father. The MM green world is vestigial, represented by the moated grange of Mariana.

[168] The prison, usually one where the hero confronts death, is part of the dialectic. MM, with the Duke’s curious psychopomp role; Cy, with the oracular jailer; T, where the Court Party is in effect imprisoned.

[169] The fr.-dr. [father-daughter] relationship is, then, always related to the 2nd world, assuming that Isabella’s (ugh) chastity is as much a part of it as Marina’s or Miranda’s. Note the Senior-Rosalind relation in AY. Great to-do about who Perdita’s father is, but the same rejoining theme. Also in Cy when the false mother is expelled. There are of course regular heavy fathers: Polixenes, Egeus, Shylock of the old law, and parody situations like TS, with its (parodied) Perseus overtones. But the point is important because the heroine as black bride, disguised as a boy, is an Eros figure like Puck & Ariel, who are directed by an old man, & who are technically male but to whom the ordinary categories of sex hardly apply. Cf. Cherubino, another androgynous sleeping beauty or Endymion figure, wondering what is “fuori di me” [outside of myself], & thanks to Mozart the most haunting & disturbing of all such figures.120

[170] Well, I’ve got the green world & the closely parallel MV scheme, where Shylock & Portia’s father represent old & new law, justice & mercy, two views of value, the ducats & Leah’s ring vs. the caskets. Here the prison-confrontation with death is a trial. Now: in the romances the green world becomes a natural society armed with magic: it enters & conquers the court, though only through this “real princess” disguise. Belarius in Cy; Bohemia in WT; the island (vs. Milan) in T.

[171] Peroration to P is creative anachronism & dialectic of two worlds; to Cy is rep. [repetition] of MA (Medit.-Atlantic) & historical perspective of 3 Troys & Xn offstage (bring up AC & Antiochus); to WT is the separation of society & idiotes worlds (no voluntary idiotes in WT; even Perdita has to marry, unless it’s the sacrificial victim Mamillius); to T is the leviathan & water business. WT & the pharmakos as state, not as person.

[172] Sea comedies have the theme of perilous landing among enemies (Antonio in TN), an insistence on “perchance” & hazard, & an insistence on madness & hallucination.

[173] The comic paravritti121 isn’t reached until the final marriages have been consummated—in other words, until the heroines get screwed. That’s one reason for the importance of chastity.

[174] In II in IV on the sea comedies:

leviathan arch, [archtype] Falstaff in MW.122

CE: descent into water: the cook.

MV: Argonaut voyage; the shift in fortune

TN: perilous landing

P: Jonah imagery & the ark

T: peroration. If so, preface with the two leviathan quotes;123 if not, follow with them.

[175] I.

Ass-patching: cf. the managerial role of Gower with that of Jonson. Gower is oracular: you must accept the story. Jonson invites you to keep your critical faculties at least half awake.124

[176] Denver: a rewrite of the present IV, a second twist,125 including:

exhaustive analysis of the apocalyptic symb [symbolism] in CE.

of the Biblical imagery in the sea group:

Paul’s journey in Acts. Ephesus.

Esau & Jacob twins. Jonah.

Prodigal Son in MV.

Merchandise & exchange: treasure in sea vs.

wisdom or kingdom of heaven.

Antiochus-Herod.

analysis of time in CE & T.

[177] What does the word Pericles mean? Or is it intended only to contain the English word “perils”? Does it mean “far-famed”?126

[178]127 L. [Luvah]

TC: the Greek conference is pure de facto strategic power: the Trojan one is a de jure rational analysis overruled by what we’d call existential absurdity.

[179] Ur. [Urizen]

In the daylight world of history, Owen Glendower’s magic is merely a neurotic obsession, and Hotspur’s contempt for music & poetry is a sign that he belongs wholly to nature as an amoral force. He loses because, like Troilus, he has too little sense of cosmic order.128 The de facto heroes are H4, H5, Octavian & Ulysses.

[180] Ur.

H5 is a problem play in the sense that we may not like its hero & may feel that the “original audience” did. The wheel of history always has utter ruthlessness at its nadir: every crest sits on top of a prison.

[181] Th. [Tharmas]

1H4 is a very great play; 2H4 interesting chiefly as showing Shakespeare’s approach to a pot-boiler: fake history, rewritten comedy (Falstaff’s corrupt recruiting methods are made with great energy & point in the first play). The main structural principle is the dialectic with the real father-figures, H4, Falstaff, & the Chief Justice. The scenes with Doll Tearsheet are well on the way to the brothels of MM & P.

[182] Ur.

H5: Note the phrase “disguising nature” & later “defective nature” in Burgundy’s speech,129 to indicate what order of nature we’re in.

[183] Ur.

The categories of tragedy are being and time, which is why I think Heidegger ought to be able to tell me something about tragedy. Being is the “Apollonian” static order of nature and degree; time is the “Dionysiac” action that runs across it horizontally.130 Ulysses’ two speeches.

[184] Time is really action occurring linked in the rhythm of time as we know it: the linear time which is not exactly clock time, but still has the kind of rhythm symbolized by the tide: Brutus, Antonio. The Augenblick131 or moment of fortune. It’s always wrong, hence the beat of time in tragedy is drunk or mad. Time in comedy is faerie time, the leisurely sensual moment that brings revelation out of complexity. Time in comedy is thus in counterpoint with the action & the being [becoming]: time in tragedy syncopates against being. P.R. [Paradise Regained]: Satan’s subtlest speech.132

[185] Th.

The legitimacy principle in evil: Joan of Arc to Margaret and the Thane of Cawdor from Macdonwald to Macbeth. Parody of death & revival.

[186] Three lectures, maybe: The Tragic Order, focussing on the conception of nature in Lear & the great bond in Macbeth; The Tragic Action, dealing with time & perhaps focussing on the parody action or time out of joint in Hamlet; The Tragic Image, focussing on the Egypt-world background of AC & perhaps dealing with the tragedy-romance progression.

[187] You’ll have to use your Beddoes point133 about the grotesque being the sense of the interpenetration of life & death.

[188] Note the emphasis thrown on explaining everything at the end of Hamlet, corresponding to the adjournment of the cast in comedy. In some respects we feel that the play Hamlet is actually the story told by Horatio. Is this done in other plays, or is it specific to the sense of Hamlet as a “problem” play?

[189] The passing over somebody by an “election”: opening of Othello, Hamlet, the same in Act I of Macbeth which reminds me of PL.V [Paradise Lost, bk. 5]. Antony & Caesar. Something very central to tragedy here. The reverse of it is the settling on somebody for a sacrificial election.

[190] The scholars are inclined to discount Shakespeare’s direct knowledge of Seneca; but that he knew about Senecan themes is clear enough. The opening scene of TAnd is the Hecuba theme of sacrificing a son (Astyanax?) to appease a ghost; Tamara’s reaction is like Medea. The pagan sacrifice suggests a “scourge of God” feeling to the play like Tamburlaine. The squabble over burying Titus’ son, too, is intensely Classical, whether strictly Senecan or not: there’s what seems like an allusion to Sophocles’ Ajax in the dialogue.

[191] Election: there is the passed over figure (cyclic) & the rejected figure (dialectic): the pharmakos Falstaff. The two Cawdors in the Macbeth scene: perhaps H4 is passed over by H5 in favor of the chief Justice. Not exactly passed over, but succeeded, anyway.

[192] I think of three lectures if I can get away with three: if four, I might string them along the two axes. Order & action are the speculation axis of space & time:134 the former I have most of the material for now. The other two would be Image (object) and Character (subject); only the latter, presumably the last, would better be called The Tragic Identity.

Tragic identity has to do with rejecting the ego-self as unreal or, more accurately, committed to something demonic. It’s connected with the fact that one’s reputation is closer to being one’s real self than one’s inner character, which ultimately isn’t there. Hence the desire of Hamlet & Othello to have their stories told about them after their death: hence the fear Cleopatra & Macbeth have of being held up to a derisive gaze. Being as reputation is “Apollonian.” Othello in Aleppo.

[194] I must be careful with this, though: two things seem central to tragedy: election or choice which excludes other possibilities & so repeats the original sin of getting born (Augenblick)135 and integrity, or the (illusory) desire to achieve something & leave something behind. In the other notebook I’ve noted two forms of this, Greek rather than Shakespearean: the effort to achieve a deed of glory by killing somebody, & the desire, if one is killed oneself, to get definitely buried or planted somewhere, not dissolving into a flux.

[195] Ur. except for TAnd.

The gods are essential to Greek tragedy, which without them would be purely ironic. They extend the aristocracy: the only check on their seduction of women is the slave-owner’s check: what children result from it are mortal, or slaves. The gods lose their sons in the Trojan war. In Shakespeare the gods are replaced by the order of nature: whatever is “Dionysiac” is purely human, at most ghostly. TAnd. says little about gods, but otherwise it’s Shakespeare’s chief link with Classical tragedy, corresponding to CE in comedy. There, I got finally more impressed by the differences: I may here too.