WHAT distinguishes the narcissistic disturbance? The example of a patient—Erich—may help us gain a clearer picture. It is true that Erich was somewhat unusual in that he was almost completely without feelings. But acting without feeling is, as we shall see, the basic disturbance in the narcissistic personality.

Erich consulted me together with his girlfriend, Janice, because their relationship was breaking up. They had lived together for a number of years, but Janice said that she could not marry him, however much she loved him, because something was lacking in their relationship. It left her dissatisfied, somehow empty. When I asked Erich what he felt, he said that he didn’t understand her complaint. He tried to do what she wanted; he tried to fulfill her needs. If only she would tell him what he could do to make her happy, he would try to do it. Janice said that wasn’t the problem. Something was missing in his response to her. So I asked Erich, again, what his feelings were. “Feelings!” he exclaimed. “I don’t have any feelings. I don’t know what you mean by feelings. I program my behavior so that it is effective in the world.”

How can one explain what feeling is? It is something that happens, not something one does. It is a bodily function, not a mental process. Erich was quite familiar with mental processes. He worked in a high-technology field, requiring knowledge of computer operations. Indeed, he saw the “programming” of his behavior as a key to his success.

I offered the example of how a man in love might feel his heart leap at the sight of his beloved. Erich countered that that was just a metaphor. So I asked him what he thought love was if it was not a bodily feeling. Love, he explained, was respect and affection for another person. Yet he was capable, he thought, of showing respect and affection, but that did not seem to be what Janice wanted. Other women, too, had complained about his inability to love, but he had never understood what they meant. I could only point out that a woman wants to sense that a man becomes excited and lights up in her presence. Love contains some ardor or passion, which is not simply respect or affection.

Erich responded by saying that he didn’t want Janice to leave him. He believed they could make a good breeding team and form a workable partnership. But if she left, he didn’t think he would feel any pain. Long ago, he had made himself immune to pain. As a child, he had practiced holding his breath until he didn’t feel any hurt. I asked him if it would bother him if Janice went out with other men. “No,” he answered. Would he be jealous? “What is jealousy?” he inquired. If there is no sense of hurt or loss when someone you love leaves you, there can be no feeling of jealousy. That feeling stems from the fear of a possible loss of love.

When Erich and Janice separated, she took her dog with her. One day Erich saw the dog on the street and felt a pain in his side. Quite seriously, he asked me, “Is that feeling?”

What had happened to turn a human being into a non-feeling machine? Theoretically, I speculated that there must have been either too much feeling or too little feeling in his childhood. When I mentioned these possibilities to Erich, he said both were true. His mother was always on the verge of hysteria; his father showed no feeling at all. As he described it, his father’s coldness and hostility nearly drove his mother crazy. It was nightmarish. But Erich assured me that he was not in any distress: “My lack of feeling doesn’t bother me. I get along perfectly well.” The only answer I could make was: “Dead men have no pain and nothing bothers them. You have simply deadened yourself.” I thought this remark would sting him. His reply amazed me. “I know I’m dead,” he said.

Erich explained, “When I was young, I was terrified at the thought of death. I decided that if I were already dead, I would have nothing to fear. So I considered myself to be dead. I never thought I would reach the age of twenty. I am surprised I am still alive.”

Erich’s attitude to life must strike the reader as weird. He saw himself as a “thing”; he even used the word “thing” in describing his self-image. As an instrument, his purpose was to do some good for other people, although he admitted that he derived vicarious satisfaction from their responses. For example, he described himself as a very good sexual partner, capable of giving a woman much pleasure. His girlfriend added, “We have good sex, but we don’t make love.” Being emotionally dead, Erich derived little bodily pleasure from the sexual act. His satisfaction stemmed from the woman’s response. But because of his lack of personal involvement, her climax was limited. This was something Erich could not understand. I explained that a man’s orgastic response heightens and deepens a woman’s excitement and brings her to a more complete orgasm. By the same token, a woman’s response increases the man’s excitement. Such mutuality, however, can occur only on the genital level, that is, in the act of intercourse. Erich admitted that he used his hands to bring a woman to climax because they were more sensitive than his penis. In effect, his lovemaking was more a servicing of the woman than an expression of passion. He had no passion.

Yet Erich could not be fully without feeling. If he had had absolutely no feeling, he would not have consulted me about his situation. He knew something was wrong, yet he denied any feeling about it; he knew he should change, yet he had developed powerful defenses to protect himself. One cannot attack such defenses unless one fully understands their function, and then only with the patient’s cooperation. Why had Erich erected such powerful defenses against feeling? Why had he buried himself in a characterological tomb? What was he really afraid of?

I believe the answer is insanity. Erich claimed that he was afraid of death, which, I think, was true. But his fear of death was conscious, while his fear of insanity was unconscious and, therefore, deeper. I believe that the fear of death often stems from an unconscious death wish. Erich would rather have been dead than crazy. What this means is that he was closer to insanity than to death. He was convinced (albeit unconsciously) that to allow any feeling to reach consciousness would crack a hole in the dam; he would be flooded and overwhelmed by a torrent of emotion, driving him crazy. In his unconscious mind, feeling was equated with insanity and with his hysterical mother. Erich identified with his father and equated will, reason, and logic with sanity and power. He pictured himself as a “sane” person who could study a situation and react to it logically and efficiently. Logic, however, is only the application of certain principles of thought to a given premise. What is logical, therefore, depends on the premise one starts from.

I pointed out to Erich that insanity describes the state of a person who is out of touch with reality. Since feelings are a basic reality of a human life, to be out of touch with one’s feelings is a sign of insanity. From this point of view, I indicated, Erich would be considered insane, despite the apparent rationality of his behavior. This suggestion that he might be crazy had a strong effect on Erich, and he asked me several questions about the nature of insanity. I explained to him that feelings are never crazy; they are always valid for the person. When, however, one cannot accept or contain one’s feelings, when they seem to conflict with rational thought, one may experience oneself as split or crazy—the feelings just don’t make “sense.” But to deny one’s feelings makes no sense either. One can do this only by dissociating the ego from the body, the foundation of one’s aliveness.1 And one has to keep up a constant effort to suppress all feeling, to act “as if.” It is tiring and pointless. I compared Erich to a fugitive from justice, who dares not surrender yet who finds that the strain of hiding is unbearable. Peace can come only with surrender. If Erich could see and accept that his attitude was really insane, he would be sane. This explanation made a lot of sense to him.

What can we learn about narcissistic disturbances from Erich’s case? The most important feature, I believe, is the lack of feeling. Although Erich had cut off his feelings to an extreme degree, such a lack or denial of feeling is typical of all narcissistic individuals. Another aspect of narcissism that was evident in Erich’s personality was his need to project an image. He presented himself as someone committed to “doing good for others,” to use his words. But this image was a perversion of reality. What he called “doing good for others” represented an exercise of power over them which, despite his stated good intentions, verged on the diabolical. Under the guise of doing good, for instance, Erich exploited his girlfriend: He got her to love him without any loving response on his part. Such exploitativeness is common to all narcissistic personalities.

A question comes up here: Can one call Erich grandiose in his exercise of power? After all, he described himself as a “thing,” hardly an overblown self-image. But the “he” who observed himself, the “I” who controlled the thing, was an arrogant superpower. This arrogance of the ego is found in all narcissistic personalities, regardless of their lack of achievement or self-esteem.

Through Erich, we have begun to glimpse a portrait of the narcissist. But how can we define a narcissist more precisely? In common parlance, we describe a narcissist as a person who is preoccupied with him- or herself to the exclusion of everyone else. As Theodore I. Rubin, noted psychoanalyst and writer, says, “The narcissist becomes his own world and believes the whole world is him.”2 This is certainly the broad picture. A closer view of narcissistic personalities is given by Otto Kernberg, a prominent psychoanalyst. In his words, narcissists “present various combinations of intense ambitiousness, grandiose fantasies, feelings of inferiority and overdependence on external admiration and acclaim.” Also characteristic, in his opinion, are “chronic uncertainty and dissatisfaction about themselves, conscious or unconscious exploitiveness and ruthlessness toward others.”3

But this descriptive analysis of narcissistic behavior only helps us to identify a narcissist, not to understand him or her. We need to look beneath the surface of behavior to see the underlying personality disturbance. The question is: What causes a person to be exploitative and act ruthlessly toward others and at the same time suffer from chronic uncertainty and dissatisfaction?

Psychoanalysts recognize that the problem develops in early childhood. Kernberg points to the young child’s “fusion of ideal self, ideal object and actual self-images as a defense against an intolerable reality in the interpersonal realm.”4 In nontechnical language, Kernberg is saying that narcissists get hung up on their image. In effect, they cannot distinguish between an image of who they imagine themselves to be and an image of who they actually are. The two views have become one. But this statement is not yet clear enough. What happens is that the narcissist identifies with the idealized image. The actual self-image is lost. (Whether this is so because it has become fused with the idealized image, or is discarded in favor of the latter, is relatively unimportant.) Narcissists do not function in terms of the actual self-image, because it is unacceptable to them. But how can they ignore it or deny its reality? The answer is by not looking at the self. There is a difference between the self and its image, just as there is between the person and his or her reflection in a mirror.

Indeed, all this talk of “images” betrays a weakness in the psychoanalytic position. Underlying the psychoanalytic explanation of narcissistic disturbances is the belief that what goes on in the mind determines the personality. It fails to consider that what goes on in the body influences thinking and behavior as much as what goes on in the mind. Consciousness is concerned with (or even dependent on) images that regulate our actions. But we should remember that an image implies the existence of an object which it represents. The self-image—whether grandiose, idealized, or actual—must bear some relation to the self, which is more than an image. We need to direct our attention to the self, that is, the corporeal self, which is projected onto the mind’s eye as an image. Simply put, I equate the self with the living body, which includes the mind. The sense of self depends on the perception of what goes on in the living body. Perception is a function of the mind and creates images.

If the body is the self, the actual self-image must be a bodily image. One can only discard the actual self-image by denying the reality of an embodied self. Narcissists don’t deny that they have bodies. Their grasp of reality is not that weak. But they see the body as an instrument of the mind, subject to their will. It operates only according to their images, without feeling. Although the body can function efficiently as an instrument, perform like a machine, or impress one as a statue, it then lacks “life.” And it is this feeling of aliveness that gives rise to the experience of the self.

Clearly, in my opinion, the basic disturbance in the narcissistic personality is the denial of feeling. I would define the narcissist as a person whose behavior is not motivated by feeling. But, still, we are left with the question: Why does someone choose to deny feeling? And related to this is another question: Why are narcissistic disorders so prevalent today in Western culture?

In general, the pattern of neurotic behavior at any particular time reflects the operation of cultural forces. In the Victorian period, for example, the typical neurosis was hysteria. The hysterical reaction results from the damming up of sexual excitement. It may take the form of an emotional explosion, breaking through restraining forces and overwhelming the ego. The person may then cry or scream uncontrollably. If, however, the restraining forces retain their hold, clamping down on any expression of feeling, the person may faint instead, as many Victorian women did when exposed to some public manifestation of sexuality. In other cases, the attempt to repress an early sexual experience, along with sexual feeling, may produce what is called a conversion symptom. Here the person displays some functional ailment, such as paralysis, although no physical basis for this can be found.

It was through his work with hysterical patients that Sigmund Freud began to develop psychoanalysis and his thinking on neurosis. Yet it is important to retain a picture of the society in which his observations were made. Generally speaking, Victorian culture was characterized by a rigid class structure. Sexual morality and sexual prudery were the avowed standards, with restraint and conformity the accepted attitudes. Manners of speech and dress were carefully controlled and monitored, especially in bourgeois society. Women wore tight-fitting corsets and men stiff collars. Respect for authority was the established order. The effect was to produce in many people a strict and severe superego, which limited sexual expression and created intense guilt and anxiety about sexual feeling.

Today, about a century later, the cultural picture has shifted almost 180 degrees. Our culture is marked by a breakdown of authority in and out of the home. Sexual mores seem far more easygoing. The ability of people to move from one sexual partner to another approaches their physical ability to move from one place to another. Sexual prudery has been replaced by exhibitionism and pornography. At times one wonders if there is any acceptable standard of sexual morality. In any case, one sees fewer people today who suffer from a conscious sense of guilt or anxiety about sexual feeling. Instead, many people complain about an inability to function sexually or a fear of failure in sexual performance.

Of course this is an oversimplified comparison of Victorian and modern times. Yet it can serve to underscore the contrast between the hysterical neurotics of Freud’s time and the narcissistic personalities of ours. Narcissists, for instance, do not suffer from a strict, severe superego. Quite the contrary. They seem to lack what might be considered even a normal superego, providing some moral limits to sexual and other behavior. Without a sense of limits, they tend to “act out” their impulses. There is an absence of self-restraint in their responses to people and situations. Nor do they feel bound by custom or fashion. They see themselves as free to create their own life-styles, without societal rules. Again, quite the opposite of the hysterics of Freud’s time.

It isn’t only the behavioral picture that reveals the contrast; a similar opposition holds on the level of feeling. Hysterics are often described as oversensitive, as exaggerating their feelings. Narcissists, on the other hand, minimize their feelings, aiming to be “cool.” Similarly, hysterics appear to be burdened by a sense of guilt from which narcissists seem relieved. The narcissistic predisposition is to depression, a sense of emptiness or no feeling, whereas in hysteria the predisposition is to anxiety. In hysteria there is a more or less conscious fear of being overwhelmed by feeling; in narcissism this fear is largely unconscious. But these are theoretical distinctions. Often one finds a mixture of anxiety and depression because elements of both hysteria and narcissism are present. This is especially true of the borderline personality, a variety of the narcissistic disturbance which I will discuss later in this chapter.

Let us return to our contrasting pictures of the two cultures. Victorian culture fostered strong feelings but imposed definite and heavy restraints on their expression, especially in the area of sexuality. This led to hysteria. Our present-day culture imposes relatively fewer restraints on behavior, and even encourages the “acting out” of sexual impulses in the name of liberation, but minimizes the importance of feeling. The result is narcissism. One might also say that Victorian culture emphasized love without sex, whereas our present culture emphasizes sex without love. Allowing for the fact that these statements are broad generalizations, they bring into focus the central problem of narcissism: the denial of feeling and its relation to a lack of limits. What stands out today is a tendency to regard limits as unnecessary restrictions on the human potential. Business is conducted as if there were no limit to economic growth, and even in science we encounter the idea that we can overcome death, that is, transform nature to our image. Power, performing, and productivity have become the dominant values, displacing such old-fashioned virtues as dignity, integrity, and self-respect (see Chapter 9).

Of course, narcissism is not unique to the present age. It existed in Victorian times and throughout civilized history. Nor is the interest in narcissistic disturbances new to psychology. Already in 1914, Freud made narcissism the subject of a study. Starting from the observation that the term was originally applied to individuals who derived an erotic satisfaction from looking at their own bodies, he quickly saw that many aspects of this attitude could be found in most persons. He even thought that narcissism might be part of the “regular sexual development of human beings.”5 Originally, according to Freud, we have two sexual objects: ourselves and the person who cares for us. This belief was based on the observation that a baby can derive some erotic pleasure from his or her own body as well as from the mother’s. With this in mind, Freud postulated the possible existence of “a primary narcissism in everyone which may in the long run manifest itself as dominating his object-choice.”6

The question here is whether there is a normal stage of primary narcissism. If there is, then a pathological outcome may be viewed as the failure of the child to move from the stage of self-love (primary narcissism) to true object (other-directed) love. Implicit in this emphasis on a failure of development is the idea of a lack that blocks normal growth. To my mind, what is more important is the idea that narcissism results from a distortion of development. We need to look for something the parents did to the child rather than simply what they failed to do. Unfortunately, children are often subjected to both kinds of trauma: Parents fail to provide sufficient nurturing and support on an emotional level by not recognizing and respecting their children’s individuality, but they also seductively try to mold them according to their image of how they should be. The lack of nurturing and recognition aggravates the distortion, but it is the distortion that produces the narcissistic disorder.

I don’t believe in the concept of a primary narcissism. Instead, I regard all narcissism as secondary, stemming from some disturbance in the parent-child relationship. This view differs from that of most ego psychologists, who identify pathological narcissism as the result of a failure to outgrow the primary narcissistic state. Their belief in a primary narcissism rests largely on the observation that infants and young children see only themselves, that they think only of themselves and live only for themselves.

For a short time after birth, infants do seem to experience the mother as part of themselves, as she was when still in the womb. The newborn’s consciousness has not developed to the point of recognizing another person’s independent existence. That consciousness develops quickly, however. Infants soon show that they recognize the mother as an independent being (by smiling at her), although they still function as if the mother were there only to satisfy their needs. This expectancy on the part of the baby—that mother will always be there to respond—has been referred to as infantile omnipotence. The term, however, seems unfortunate. As the British psychoanalyst Michael Balint points out, “It is taken for granted (by the infant) that the other partner, the object on the friendly expanse, will automatically have the same wishes, interests, and expectations. This explains why this is so often called the state of omnipotence. This description is somewhat out of tune; there is no feeling of power, in fact, no need for either power or effort, as all things are in harmony.”7

The issue of power, however, often enters into the relationship between parents and children. Many mothers resent the child’s taking it for granted that she, the mother, will always be there to respond to the child’s needs, regardless of her feelings. Children are often accused of seeking power over their parents when all they want is to have their needs understood and responded to. Infants are totally dependent and can only appeal through crying. Children are also really powerless. In fact, it is the parents who are omnipotent with respect to children, for they literally hold the power of life and death over children. Why, then, do we adults often refer to the baby as “his royal highness”? The idea of infantile omnipotence suggests a grandiosity that would justify the assumption of a primary narcissism. Yet I believe it is all in the adult mind. The parent’s narcissism is projected onto the child: “I’m special and therefore my child is special.”

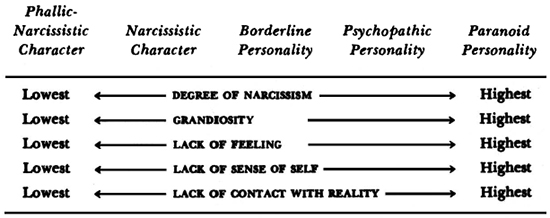

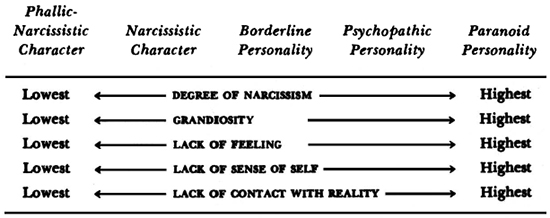

So far we have looked at narcissism as a whole. But narcissism covers a broad spectrum of behavior; there are various degrees of disturbance or loss of self. I distinguish five different types of narcissistic disorder, according to the severity of the disorder and its special features. Thus, the differences are both quantitative and qualitative. The common element, however, is always narcissism.

In order of increasing narcissism, the five types are:

1. Phallic-Narcissistic character

2. Narcissistic character*

3. Borderline personality

4. Psychopathic personality

5. Paranoid personality

What we have, then, is a spectrum of narcissistic disorders, from least to most severe. Using this spectrum, we can see more clearly the relationships between different aspects of the narcissistic disorder. For instance, the degree to which the person identifies with his or her feelings is inversely proportional to the degree of narcissism. The more narcissistic one is, the less one is identified with one’s feelings. Also, in this case, one has a greater identification with one’s image (as opposed to self), along with a proportionate degree of grandiosity. In other words, there is a correlation between the denial or lack of feeling and the lack of a sense of self.

Recall that I equate the self with feelings or with the sensing of the body. The relation between narcissism and the lack of a sense of self is better understood if one thinks of narcissism as egotism, as an image rather than a feeling focus. The antithesis between the ego (a mental organization) and the self (a body/feeling entity) exists in all adults or, rather, in anyone who has developed a certain self-consciousness, which derives from the ability to form a self-image.* Because this ability is a function of the ego, narcissism is properly seen as a disturbance of ego development.

But being self-conscious or having an image of the self is not narcissistic unless the image has a measure of grandiosity. And what is grandiose can only be determined by reference to the actual self. If one has an image of oneself as attractive and appealing to the opposite sex, that image is not grandiose if one is in fact attractive and appealing. Grandiosity, and thus narcissism, is a function of the discrepancy between the image and the self. That discrepancy is at a minimum in the case of the phallic-narcissistic character, which is why that personality structure is closest to health.

In its least pathological form, narcissism is the term applied to the behavior of men whose egos are invested in the seduction of women. It is these personalities who have been described as phallic-narcissistic in the psychoanalytic literature. Their narcissism consists of an inflation of and preoccupation with their sexual image. Wilhelm Reich introduced this term in 1926 to describe a character type that was somewhere between the compulsion neurosis and hysteria. “The typical phallic-narcissistic character,” he writes, “is self-confident, often arrogant, elastic, vigorous and often impressive.”8

The importance of the concept of phallic-narcissism is twofold. First, it underlines the intimate connection between narcissism and sexuality—specifically, sexuality in terms of erective potency, the symbol of which is the phallus. Second, it describes a relatively healthy character type, in whom the narcissistic element is at a minimum. As Reich explains, even though phallic-narcissists’ relationship to a loved person is more narcissistic than object-libidinal, “they often show strong attachments to people and things.” Their narcissism is manifested in an “exaggerated display of self-confidence, dignity and superiority.” But “in relatively unneurotic representatives of this type, social achievement, thanks to the free aggression, is strong, impulsive, energetic and usually productive.”9

I have always considered myself a phallic-narcissistic character, and so I have some idea of how this personality type develops. I know that I was the apple of my mother’s eye. She looked to me to fulfill her ambitions. I was more important to her than my father was. And although my mother was not overtly sexually seductive, the implications of her feelings were sexual. Her emotional investment in me provided an extra measure of energy and excitement to my personality. Yet her need to possess me, and thus control me, diminished my sense of self. In this situation, my ego became bigger than my self, making me a narcissistic personality. On the other hand, through my identification with my father, who was simple, hardworking, and pleasure loving, I retained my feeling for the life of the body, which is at the core of the feeling of self.

But what about the female in all this? The female counterpart to the phallic-narcissistic male is the hysterical character type.* Here I am using the term “hysteria” (from the Greek hystera, or “womb”) to denote the strong identification of this personality with feminine sexuality. The hysterical character is not given to overt hysterics (a symptom found in many schizophrenic personalities). It is more that she, like the phallic-narcissistic male, is preoccupied with her sexual image. She, too, is self-confident, often arrogant, vigorous, and impressive. Her narcissism comes out in a tendency to be seductive and to measure her value by her sexual appeal, based on her “feminine” charms. She is and she feels herself to be attractive to men, and she has a relatively strong sense of self. She differs from the phallic-narcissistic male in that softness is her essential quality (the softness of the womb), as opposed to his identification with the hardness of his erection. There are, of course, women who can be considered phallic in their structure and behavior. They have less feeling, sexual and otherwise, than the hysterical character and are more narcissistic, more committed to an image of superiority than to the feeling self. They belong to the narcissistic character type, which I shall describe next.

Narcissistic characters have a more grandiose ego image than phallic-narcissists. They are not just better, they are the best. They are not just attractive, they are the most attractive. As psychiatrist James F. Masterson points out, they have a need to be perfect and to have others see them as perfect.12 And actually, in many cases, narcissistic characters can display numerous achievements and seeming success, for they often show an ability to get along in the world of power and money. They may think too highly of themselves, but others may think highly of them, too, because of their worldly success. Nevertheless, their image is grandiose; it is contradicted by the reality of the self. Narcissistic characters are completely out of place in the world of feeling and do not know how to relate to other people in a real, human way.

One way of looking at the differences between the phallic-narcissist and the narcissistic character is through their fantasies. As he walks down the street, for instance, the phallic-narcissistic male may imagine that women look at him with admiration and men with envy. On some level, he sees himself as superior, but he also recognizes that he may be inferior to others. When the narcissism is more pronounced, the fantasy might be: “When I walk down the street, I have the feeling that people step aside for me. It’s like the parting of the waters of the Red Sea to allow the Hebrews to pass through. I am proud.” This fantasy was in fact related by one of my patients, who said he realized it was irrational but it was how he felt. He identified himself unconsciously with those celebrities for whom the police make a corridor through the crowd of their admirers.

The third type of narcissist—the borderline personality—may or may not overtly show the typical symptoms of narcissism. Some borderline personalities project an image of success, competence, and command in the world, which is indeed supported by achievements in the world of business or entertainment. In contrast to the front of narcissistic characters, however, this façade readily crumbles under emotional stress, and the person reveals the helpless and frightened child within. Other borderline personalities present themselves as deprived, emphasizing their vulnerability, and often clinging. In these cases, the underlying grandiosity and arrogance are hidden because they cannot be supported by proven accomplishments.

The grandiose display of narcissistic characters is a relatively effective defense against depression, and thus the façade of superiority is difficult to break down. In contrast, for borderline personalities, a show of success provides no such protection. Often these patients enter treatment with the complaint of depression. Narcissistic characters and borderline personalities may hold similar grandiose fantasies in terms of content. What differs, however, is the degree of ego strength behind these fantasies—the extent to which they are supported by a true sense of self.

The case of Richard, a borderline personality, clarifies the distinction I am making. Richard entered therapy because of depression, which was affecting both his sexual life and his work. Although he had an important job, he felt he was a failure. Perhaps, he thought, he wasn’t aggressive enough. In any case, he didn’t feel in command of the situation. Moreover, he was afraid of success.

There was nothing in Richard’s appearance to suggest a narcissistic problem; he did not present a commanding or self-consciously handsome appearance. But something in his manner made me question his self-image. When I asked him to describe himself, he replied, “I feel I am strong, energetic, capable. I feel I am smarter and more competent than all others, and I should be recognized as such. But I hold myself back. I was born to be on top. I was born a king, superior to everyone else. I feel the same way on the sexual level. Sex should just be offered to me. Women should cater to my needs, but I act out the opposite. I hold back.”

The idea of being “born a king,” of being extremely special, certainly dovetails with the fantasies of the narcissistic character. But Richard repeatedly excuses himself, saying: “I hold back.” In contrast, narcissistic characters do not hold back. They have the necessary aggression to achieve some degree of success, suggesting an ego strength that the borderline personality lacks. One should not, however, underestimate the grandiosity of the borderline. Though seemingly less evident than in the narcissistic character, it is no less present, as another example shows.

Carol had been in therapy for several years with complaints of depression and feelings of worthlessness. That such feelings may cover underlying feelings of superiority should not be surprising. We have known for a long time that feelings of superiority and inferiority exist together. If one is on top, the other is underneath.

In describing herself to me, Carol commented: “I was a superior student at college. I always got the highest marks. And I did equally well in graduate school. I was considered the top student and congratulated on my abilities. My professors raved about me. They told me I was exceptional. I thought I was great. However, in my work now I often sense that I do not know what to do. I feel awful about myself. It was the same at home when I was young. I was great one minute and shit the next. My mother would say I was the most beautiful, the most brilliant child. The next day she said it wasn’t true, she had said it just to bolster me up because I was so pathetic. She built me up one minute, then smashed me down the next.”

Carol’s remarks point out one difference between narcissistic characters and borderline personalities. Although the narcissistic character’s self-image is grandiose, it is in less direct conflict with reality, for it has never truly been smashed down. In contrast, borderline personalities find themselves caught between two contradictory views—they are either totally great or totally worthless. The fantasy of “secret” greatness may then become all the more necessary, to counter the reality threat of worthlessness. There is thus less connection between the inner (fantasy) image and the actual self, however deprecatory the patient’s comments may sound.

Still, I must emphasize that the differences between the various narcissistic types are largely a matter of degree. Some borderline patients, despite their feelings of inferiority and insecurity, attain a fair measure of success in their work. And some narcissistic characters are troubled by a sense of inadequacy despite their façade of self-assurance and command. In these cases, one may be uncertain about the exact diagnosis. Granted, an exact diagnosis is not necessary to begin treatment, for one should treat the individual, not the symptom. Nevertheless, diagnosis can help us to better understand the underlying personality disturbance. With the diagnosis of narcissistic character disorder, for instance, we would expect the patient to have a better developed ego and sense of self than the borderline personality, so our emphasis might be slightly different in the treatment.

This distinction poses a theoretical problem for many psychoanalytic writers on the subject who see narcissism as resulting from the failure of ego development. As Masterson explains, “in developmental terms, although the self-object representation is fused, the narcissistic [character] seems to get the benefit for ego development that is believed to come about only as a result of separation from that fusion.”13 To these writers, grandiosity represents a continuation of infantile omnipotence, which stems from the child’s failure to form an identity separate from that of the primary love object, the mother. The fusion of self and object representations is characteristic of the infantile state. The problem can be rephrased as follows: If, on an emotional level, the narcissistic character is still an infant tied to mother, how can we explain his or her possession of an aggression that is oriented to the world and leads to achievements beyond the capacity of the borderline personality?

I don’t believe this problem can be resolved if we rely on the premise of infantile omnipotence and regard narcissism only as the result of a failure of development. If we drop the concept of infantile omnipotence, then we may seek the cause for grandiosity in the parents’ relation to the child, rather than in the child’s relation to the parents. A boy doesn’t think himself a prince through any failure of normal development. If he believes himself to be a prince, it is because he was raised in that belief. How children see themselves often reflects how their parents saw and treated them.

Moving along our spectrum to the psychopathic personality, we would expect to find an even greater degree of grandiosity, whether manifest or latent. All psychopathic personalities consider themselves superior to other people and show a degree of arrogance that verges on contempt for common humanity. Like other narcissists, they deny their feelings. Particularly characteristic of psychopathic personalities is a tendency to act out, often in an antisocial way. They will lie, cheat, steal, even kill, without any sign of guilt or remorse. This extreme lack of human fellow-feeling makes psychopathic personalities very difficult to treat.

The term “acting out” describes an impulsive type of behavior that ignores the feelings of other persons and is generally destructive to the best interests of the self. The impulses underlying this behavior stem from experiences in early childhood that were so traumatic and so overwhelming that they could not be integrated into the developing ego. As a result, the feelings associated with these impulses are beyond the ego’s perception. The action is therefore taken without any conscious feeling. Murder in cold blood is an extreme example of psychopathic acting out. But acting out per se is not limited to antisocial behavior. Alcoholism, drug addiction, and promiscuous sexual behavior may all be regarded as forms of acting out.

Acting out, however, is not limited to the psychopathic personality. Masterson recognizes that narcissistic characters and borderline personalities also act out. But there is a difference. As he puts it, “The acting out of the psychopath, compared to that of the borderline or narcissistic [character] disorders, is more commonly antisocial and usually of long duration.”14 Here, again, we see that the differences are a matter of degree rather than of kind.

Because psychopathic personalities represent an extreme, they provide many insights into the nature of narcissism. Not only do they portray in sharp relief narcissists’ tendency to act out (which, in other cases, is less antisocial), but they also shed light on narcissists’ underlying grandiosity. It is significant, for instance, that narcissistic characters and psychopathic personalities show a need for instant gratification, an inability to contain desire or tolerate frustration. One could regard this weakness as an expression of infantilism in the personality, but I believe it has a different meaning and origin, reflecting the deficient sense of self. One must remember that in other respects—namely, in their ability to manipulate people, organize and promote schemes, and attract followers—narcissistic characters and psychopathic personalities are anything but infantile.

In saying this, I should add that psychopathic personalities are not necessarily what society calls “losers.” There are successful psychopaths according to Alan Harrington, who made a study of these personalities—“brilliant, remorseless people with icy intelligence, incapable of love or guilt, with aggressive designs on the rest of the world.”15 Such an individual may be an able lawyer, executive, or politician. “Instead of murdering others,” Harrington comments, this person “might become a corporate raider and murder companies, firing people instead of killing them, and chopping up their functions, rather than their bodies.”16 Ironically, the key to this kind of “success” is the person’s lack of feeling—which is the key to all narcissistic disturbances. As we have seen, the greater the denial of feeling, the more narcissistically disturbed the individual is.

At the other end of the spectrum, furthest removed from health, is the paranoid personality showing clear-cut megalomania. Paranoid personalities believe that people are not only looking at them but also talking about them, even conspiring against them, because they are very special and very important. They may believe they have extraordinary powers. When they become unable to distinguish fantasy from fact, their insanity is clear. In that case, we are dealing with full-fledged paranoia—a psychotic rather than a neurotic condition—and the treatment differs. Nevertheless, even in such extreme cases, we find most of the characteristics of narcissism: extreme grandiosity, a marked discrepancy between the ego image and the actual self, arrogance, insensitivity to others, denial, and projection.

Just as it may be difficult to distinguish between the narcissistic disturbances on our spectrum, it may at times be hard to draw a sharp line between neurosis and psychosis. The very term “borderline” was created to denote a personality structure that is somewhere in between, both sane and insane. If sanity is measured by the congruence of one’s ego image with the reality of the self or body,17 then we may postulate that there is a degree of insanity in every narcissistic disturbance. To return to the beginning, Erich’s self-representation as a “thing” denotes a degree of unreality that borders on the insane.