Careyhurst and ditch, Box Elder Creek. J. E. Stimson Collection, Wyoming State Archives.

2. PUBLIC ORDER VS. PRIVATE GAIN

I was told later that two men were guarding us kids from the creek bank 200 yards away with Winchesters.

—JESSE SLICHTER, RECALLING HIS FAMILY’S STRUGGLE FOR LAND AND WATER.1

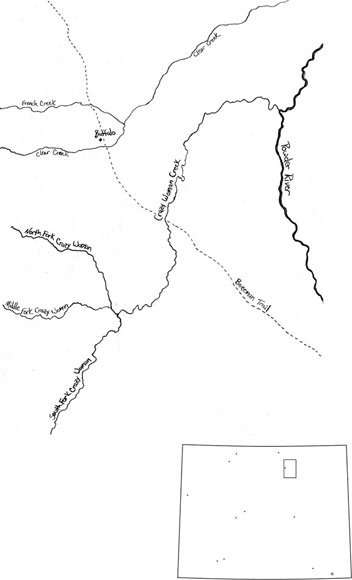

Places: Box Elder Creek, central Wyoming; Crazy Woman Creek, northeast Wyoming’s Big Horn Mountains.

Time: 1890s.

Careyhurst and ditch, Box Elder Creek. J. E. Stimson Collection, Wyoming State Archives.

THE WORLD IN WHICH Mead sought to work shared, of course, very little of the logic with which he shaped his new water system. Wyoming in the late 1880s and early 1890s was an oddity in nineteenth-century America, an anachronistic “frontier” between the two developed coastlines symbolizing the Gilded Age. As such, it played host to two worlds. For many, it was a place to build a cabin or a dugout, to start a new life. For a few others—those with enough money to play—it had been a gaming table made of grass; it was not a place to live.

As Mead set up his water system, those two worlds were still in conflict, and the friction produced sparks that cast a lurid light, as in the Johnson County War. Mead’s vision of a public interest governing the distribution of water made headway, but his water system inevitably bore the imprint of the times. Power contests that used water as a weapon could not be stopped by Mead’s system and his few lieutenants working across a vast territory. Most people, as Mead well knew, believed that water like land could and should be the basis of private property, and therefore potentially of wealth. There was plenty of temptation and opportunity to make one’s own rules.

Yet Mead’s work had an impact. His system cut down to size the dreams and sometime pretensions of the 1870s and 1880s; it made it possible for a more stable society to take root. Gillette’s adjudication in Buffalo demonstrated that. Mead’s concept of an overarching public interest in water and its orderly use slowly shaped people’s reality. The frontier nature of nineteenth-century Wyoming affected Mead’s system, but his logic also changed the Wyoming that moved into the twentieth century. Each left its mark on the other.

Events in two locations demonstrate how that happened. The first was on Box Elder Creek, a small tributary of the North Platte River in central Wyoming.

The story of Box Elder Creek is dominated by one figure: Joseph Carey. He was originally an ally of Francis Warren and even did Warren’s campaigning for him in late summer 1890 when Warren was ill during the race for governor of the new state. Mead was well acquainted with Carey.2

Carey and Warren became two of the “grand old men” of the state’s political folklore. They were the vivid, long-remembered, nineteenth-century originals, emblematic of the ambitions for personal wealth from Wyoming’s resources—water, grass, or (later) minerals. With their identity and their wealth rooted in the open-range stock business, they carried the state’s nineteenth-century roots several decades into twentieth century politics. Warren, Mead’s sponsor, was territorial governor, state governor, and US senator for nearly forty years. Carey was territorial delegate to Congress and author of statehood, briefly US senator, and a one-term governor, running against Warren’s faction, just before World War I. Mead worked with them for most of his life, as he too went to work on a national level at what became the Bureau of Reclamation. Warren and Carey were not to be evaded; their goals and their way of operating were a major feature of the world in which Mead’s system had to make its way.3

There is perhaps none better than “Judge” Carey, as he was known much of his life, to represent the attractions and contradictions of the Wyoming world where Mead worked. A fellow Republican leader (later a federal judge) said of Carey years later:

Carey was perhaps the most astute and effective stump speaker Wyoming has ever produced. While his political statements were not strictly based on recorded facts, he was able to convince the voters in an unusual way of the logic of his arguments.

I recognized Carey as a man of pre-eminent ability and frequently remarked that any citizen of Wyoming might well feel proud of him when he appeared as he frequently did among the Governors and Statesmen of the Nation. He was a big man in big things but he was possessed of a peculiarly vindictive disposition and temperament oft-times akin to a school-girl. He took to heart any opposition to himself and punished those who had opposed him in an exceedingly icy manner.4

Carey appeared to have viewed politics and political office as matters of personal sway. By contrast, Warren took a pragmatic approach, focusing on party unity and a fine-tuned patronage machine, to make federal money an important driver of Wyoming’s economy. Warren had by far the longer political career.5

Joseph Maull Carey came to Wyoming as a bright young man from a well-established East Coast family, looking to make his fortune. He had sat out the Civil War and came to the new territory of Wyoming as its first US attorney in 1867 when he was twenty-two, just out of law school. The job was his reward for working back home on Republican campaigns. Four years later, he was on the territorial Supreme Court, where he got his lifelong title as Judge Carey. But in 1876, just before veteran Civil War officers launched the last assaults on native tribes in Wyoming, Carey lost his court post in a factional party fight, and he turned his attention to cattle. He had fifteen thousand head brought to the North Platte River the next spring after the great grasslands north of the Platte became open for cattle herds to enter.6

Further west, on the Wind River, the Shoshone and Arapahoe were also turning to cattle. Until the mid-1870s, the Shoshone had prospered by hunting and by selling hides. The 1868 treaty creating the Wind River Reservation intended to cast the Shoshone in the role of farmers. They received initial government support in learning to farm, with some success. Their real livelihood, however, was based on hunting, until buffalo and other game became scarce. As the game herds disappeared, as their people became more impoverished, and as whites made homes and mines on the reservation, cattle herds emerged as their persistent goal. In 1872, the Shoshone sold some reservation land south of the river to the government in exchange for cattle, first running them effectively in communal herds, but then forced by the reservation agent to parcel the herd into individual ownerships. The process enabled nearby whites to buy out the herds of individual Shoshone cattle owners for cash. Congress, opposed to “perpetuation of distinctive national characteristics in our midst” and sure of the benefits of small individual farms, increasingly pushed for the native people to develop private farms on reservation land while “surplus” land on the reservation would go up for sale to new settlers. The Arapaho were forced to live on the reservation starting in 1878. Proposals and negotiations for cutting down the reservation continued for years as the world of settlement and commerce grew more active at the reservation’s borders.7

Carey, of course, was at ease in that world. Back on the Platte River, where Carey planned a cattle kingdom, he made himself a place near the river crossing at the army’s Fort Caspar. He established it personally, taking a hand in building the first one-room log ranch house himself. He also set up operations on a place about thirty miles east, near the next army outpost, Fort Fetterman. The spot he chose, where the creek called Box Elder met the river, had meadows that had been harvested for native hay in a few previous years by men who made a living as freighters and supplied beef and hay to the army and its horse herds. Carey headquartered there, south of the river, eventually naming his place Careyhurst. In 1877, he turned his cattle out to the north—swimming the herd across the sometimes treacherous river to reach the good grazing.8

Others also brought in cattle, and the new industry grew quickly, attracting investors told to expect 150 percent profit in five years from the “free grass.” Markets for beef were growing in a hungry postwar United States, and on its frontier were free pastures. That brought Wyoming its brief decade of fame, from 1876 to 1886. On the edges of the grasslands, a few mansions sprouted, where guests enjoyed multiday hunts; champagne was served at the cattlemen’s club in Cheyenne.9

Carey spent much of that decade organizing the stockmen to pursue their interests. It was a heady challenge for a lawyer, guiding a new industry working in new terrain. Helping to recast a fledgling Wyoming Stock Growers Association (WSGA) in 1874, Carey became its president at the industry’s peak in 1884–1885, just before the crash resulting from the disastrous 1886–1887 winter.10 He became a Republican national committeeman and in 1885 was sent to Congress as the sole representative of Wyoming Territory.11 Though the grazing lands were public domain subject to laws encouraging settlement and land ownership, the cattle companies’ “home ranges” extended far from headquarters without any ownership. Boundaries existed, but they ran unmarked, known only to the people in the business.12 Accompanying the joint roundups and cattle brandings, the companies and their association focused energy on blocking competition from small ranchers who were sometimes former company cowboys. The WSGA represented a majority of cattle on the range, but not the majority of cattle owners. They wanted to keep non-member operations in check and discourage the emergence of new ones, and they needed to draft strict rules to do so—association rules or, when they could swing it, official legislation of the territory. Carey and close associates did that work.13

First, the WSGA adopted an internal blacklist rule that forbade members to hire a cowboy who owned his own brand or a herd. Then, in 1884, as Carey became president of the association and then the territory’s delegate to Congress, the organization successfully shunted a “maverick law” through the Wyoming territorial legislature. The law gave the WSGA sole control in disposing of unbranded calves on the range that were found without their branded mothers—the “mavericks.” The WSGA then made sure that most of those calves went to its own members, making it all but impossible for smaller ranchers to buy the mavericks and build themselves a herd. The transparent goal was to ensure that cowboys remained wage earners, not property owners (and that anyone who had his own small herd might therefore be conveniently labeled a thief). In 1886, association members joined in a wage cut, resulting in an unprecedented cowboy strike. Not all WSGA ranches resisted striker demands to restore wages to the pre-cutback levels, but Carey and his “CY” ranch near Fort Caspar did. The WSGA’s blacklist and its maverick law—“class legislation,” in the view of the Buffalo correspondent of one Wyoming newspaper—are what led to a slow-burning discontent and ultimately a level of violence in Wyoming, demonstrated in the 1892 invasion in Johnson County, that did not mark the cattle industry in nearby Montana or Colorado.14

After the bust of 1886–1887, the surviving cattlemen, trying to become better businessmen, were haunted by the memory of carcasses piled under melting snow. Some investors discovered that their herds had been magnificent only on paper, and the surviving operations began to think seriously of feeding hay to real cattle, in winter. Native hay had been harvested for years in creek-bottom lands like Carey’s on Box Elder, but the new idea was to go further, to water whatever could be watered to raise hay and feed the herd through the winter. The companies that had pulled through the bust began to think more seriously about irrigation, on land they could own. The federal Desert Land Act, enacted a decade earlier, had made construction of irrigation ditches one way to obtain land. The law was often used by Wyoming settlers to obtain land they irrigated for farms, with a few cows and a garden. Cattle companies, too, had sometimes put it to use—for real, or with fraudulent “dummy entry-men” to claim lands laced with ditches that stayed remarkably dry, there for nothing more than to claim title to the land. Fences were sometimes strung across the public range illegally. When young Elwood Mead came to Wyoming, he reported seeing networks of dry ditches. The outsized claims to water he recorded were also sometimes the work of stockmen trying to lock water away from small settlers. The federal government’s General Land Office gathered evidence suggesting that some Wyoming stockmen had made fraudulent land claims. Carey was no exception. In 1885, he expanded his holdings on Box Elder Creek by buying out three men who had made Desert Land claims two years before; he had a contractor dig the ditches for them, paid them $48,000 for their claims, and paid the federal government its $640 fee for the 640 acres. A General Land Office investigator called foul and canceled the claims and with them Carey’s title to that land.15

Carey saw a role for small ranches and farms in Wyoming—in certain places. In 1883, well before the bad year of 1886–1887, he had joined other WSGA members in starting the prototype water development company that aimed to profit by selling irrigated land to colonists. Apparently not designed as a water monopoly of the kind Mead deplored, the company sold both water rights and land to settlers. After the crash, Carey managed to hold on to his ranches—and also, in 1888, worked with an oncoming railroad to plat some of his CY ranch into city lots for sale to make some money on the creation of the new city of Casper. As one of the authors of the WSGA’s toughest legislation, however, Carey was not friendly to settlers infringing on his world. In 1886, three would-be settlers eyeing Box Elder Creek had filed the complaint against Carey that led the General Land Office to investigate and cancel the Desert Land Claims he had bought that covered key bottom lands on the creek. The settlers moved right in on those lands the next year. Carey wouldn’t stand for it.16

One of those settlers was John Slichter, from Iowa—“very tired of the Iowa mud,” his oldest son said. Slichter came to Wyoming in 1883 with his wife and three children and settled on a small place on the North Platte River. He dreamed of breeding and selling horses and pursued that with modest means. Slichter also hauled freight, to and from the new railroad line stitching west to the new town of Casper. But Slichter’s original place on the North Platte was not ideal. The river was an unreliable neighbor, not easy to tap for irrigation water. Fed by mountain snowmelt, the Platte would surge into violent flood stage in May and occasionally cut itself a new channel—and then dwindle to a listless near-nothing in fall and winter. Box Elder Creek, flowing into the Platte a few miles upriver, had good bottom land and timber and was a far more manageable water source than the river. Slichter saw the advantages and led two other men in filing the complaint against Carey over the Desert Land Act claims Carey had bought up the year before. Slichter had the land surveyed, and he testified to federal land officers in Cheyenne, seeking to show that creek bottom land was never “desert” and then to file on it himself under the Homestead Act. Carey was still Wyoming’s delegate to Congress, but although it took a while, his title was eventually canceled. After a year in a nearby little coal town (a century later, the site of a major power plant), Slichter moved his family onto 160 acres on Box Elder. He built a small frame house there and a ditch, and he even started delivering to nearby ranchers coal dug along the creek. He grew a crop of oats. He figured he could water some one hundred head of stock and horses on the creek and irrigate to grow hay for feed. In October 1889, he began to dig a ditch. But, as he complained to Mead’s superintendent nearly a decade later, soon, “a part of my land that it was constructed for was taken from me.”17

Slichter had, of course, run afoul of Carey, who wasn’t about to lose any Careyhurst property without a fight. Carey, in turn, unwittingly ran into a witness who left a rare record of what the Judge would do to someone who got in his way.

Slichter’s oldest son, Jesse, was about ten or eleven years old at the time. The struggle between his father and Carey, in about the year 1889, was seared into his memory. Many decades later, when asked to write about family history, Jesse Slichter wrote about Carey.18

As could have been expected, the story he told is one-sided. But it is suggestive of what was said of Carey by his smaller neighbors. Carey, wrote Jesse Slichter, pushed out settlers who had come in on the canceled Desert Land entries near Careyhurst on Box Elder. The method was straightforward and nasty: Carey had his men go with wagons to the homestead cabins and dump everything people had into the creek. If possible, they did the job when the families were away.

In the case of the Slichters, Jesse wrote:

I well remember the day our time came. Two wagons and four men and the foreman, Edward David, drove into the yard. [He] ordered the wagons backed to the door but the men refused on finding a woman and children. Lots of angry words were exchanged before they left. A short time later . . . Father and Mother were arrested and ordered to appear in Glenrock, 12 miles away. Father’s lawyer advised him to leave us three kids at home alone. The same wagons appeared, but when they saw us playing in the yard, they got scared away. The judge dismissed the case. I was told later that two men were guarding us kids from the creek bank 200 yards away with Winchesters.19

Jesse Slichter took care all those years later to name Carey’s foreman because the foreman, like Carey, was not just anyone. Edward David, grandson of a wealthy family in upstate New York, had come west about six years earlier following an uncle who had been the first surveyor general of Wyoming Territory, in 1868. The surveyor general’s daughter had married another early territorial officer—Carey. Edward David was therefore a young cousin of Carey’s wife. David ran a ranch in northwest Wyoming for Carey until the 1886–1887 disaster and then came to the Platte to superintend all of Carey’s ranch interests in central Wyoming, including on Box Elder and in Casper. He soon helped organize a new county around Douglas, was elected to the territorial legislature, and became a trustee of the new University of Wyoming. To Jesse, however, he was the man who came to push the Slichters out of their new house.20

Carey won in the end, for the most part. He eventually got the key Box Elder properties back, titled to him. He was in Congress, and a Republican—and the General Land Office investigations were started by Democrats who had taken power only briefly in Washington and lost it in 1889, the year Carey got the 640 acres on Box Elder back. Carey summarized it all quickly, nine years later: “Slichter squatted on the land while it was in contest by the U.S. and afterwards had to leave it when contest was decided in our favor.” By the time he said that, Carey had built Edward David and his family a big stone house on the Careyhurst ranch, a house that was still standing nearly one hundred years later.21

John Slichter, meanwhile, didn’t give up. He had his mind set on getting a better water source than the unruly Platte. He still had his ranch on the river. He tried lengthening the ditch he’d started on Box Elder Creek so the ditch could take the creek water back to his river ranch. It took seven years to get the whole ditch dug (he had all kinds of trouble on the surveying work and nobody but young Jesse to help run the scraper for the ditch), but he did it. That was when Slichter and Carey came into conflict again. This time it was over water rights, and this time Carey did not get all his own way.22

This new confrontation started in 1898, the year Mead’s new state-supervised stream-wide adjudication process reached Box Elder Creek. James A. Johnston, the superintendent of Division I, gathered evidence on oath in April as to how much water people took and where they used it. He took most evidence in Glenrock, west of Box Elder; but he took Carey’s evidence in Cheyenne, for the Judge’s convenience. Wyoming was a small society, and Carey was a big man (and by then in a standoff with Warren as part of a bitter Republican Party feud).23

Johnston knew Carey well; he had recently been president of the irrigation colony company that Carey and the other cattlemen ran.24 Johnston was also a friend and colleague of Mead’s, having helped get Mead to Wyoming. A Democratic territorial legislator in 1888, and then a delegate to the state constitutional convention, he helped write Mead’s water language into the Wyoming Constitution. In the 1890s, Mead made him superintendent of the water division of the North Platte basin, which included the capital, Cheyenne.25

Johnston took testimony from Slichter in the 1898 dispute with Carey. Slichter declared that the ditch he had built to reach his North Platte River ranch was part of the original ditch he built from the creek to water the place on Box Elder, where Carey’s foreman came to push him out. Slichter started digging the ditch on October 14, 1889. That date would put his water rights on Box Elder ahead of some other ditches, including some of Carey’s ditches on Careyhurst. Without the 1889 date, Slichter said, he couldn’t even get enough water to keep a garden going on his lands by the river, much less to grow hay for his stock.26

Carey, for his part, stated simply that Slichter had “squatted” on Careyhurst land back in 1889 and had simply left. Carey claimed that he himself had used the ditch Slichter once built, ever since the land ownership was settled in Carey’s favor and Slichter was back on the river.27 Johnston ruled for Slichter, though he cut back the water volume in both men’s water rights. His ruling meant Slichter got reliable water from Box Elder Creek to use on his place by the North Platte. Carey didn’t lose much in terms of water for Careyhurst—he had plenty of other water rights running through a welter of ditches.28

Between the big cattleman and the small-time settler, it was not the federal land office but Mead’s water-law system—and its elaborate process of testimony and onsite inspection—that ultimately had some impact on what happened there along the Platte. Carey got rights to land and to water, but not to the exclusion of the new people coming in.

The Slichters, it turned out, were among the people who had come to stay and to build a town serving small farms and ranches, people whose families would stick around longer than the Careys. John served on the first Wyoming jury after statehood. Jesse and his brother Charley became county officers around the time of World War I and after.29

The town these people built, Douglas, took over as the local center from the remnant of Fort Fetterman, whose buildings for a time had served as the store, saloon, and hospital for the surrounding region. In those days, the area had a deputy sheriff, named Malcolm Campbell, just about Carey’s age. A Canadian farm boy, Campbell had made it to Wyoming after the Civil War and wound up a freighter, driving bull teams of supplies for the Wyoming forts while the troops were active there. In the 1870s, he too had lived on Box Elder Creek, in a little adobe house, and harvested hay there to feed the army horses at Fort Fetterman. As the wars ended and the cattle business came on, he sold out. Campbell’s place ultimately became part of Careyhurst.30

Campbell signed up as deputy near Fort Fetterman on the Platte under the county sheriff who was one hundred miles away, so he was pretty much on his own. His job was to keep some kind of order in the sudden little settlements on the edge of the great new cattle ranges. Hundreds of cowboys were soon making big wages on the range, and they would come to “town” at the old fort to spend their money. They were “young and carefree farmer boys up off the farms of the eastern states,” Campbell said. A “happy go lucky lot . . . few among them were deadly or unfriendly”—until they started drinking, Campbell recalled. Then the gunfights started. Jesse Slichter said his mother and aunt were terrified whenever John Slichter went to old Fort Fetterman for supplies. The drunken brawls could entangle bystanders.31

It sounds like the setting for an old-fashioned Western, and it was. The straggling town at old Fort Fetterman was the model, for Owen Wister, of the town where he set The Virginian. In the summer of 1885, Wister spent two months as a guest on an area ranch owned by “Major” Frank Wolcott, a Kentuckian who had fought on the Union side in the Civil War, come to Wyoming to work for the General Land Office, and become a cattleman later investigated by the General Land Office for fraud. On his visit, Wister noted that Wolcott was battling squatters nearby—trying direct intimidation and blackballing them with the Stock Growers Association so they couldn’t hire out part-time with cattle companies to bring in money while proving up on their homesteads.32

In 1885, unknown to Wister, Wolcott was beginning to take out heavy loans that, after the 1886–1887 drought and hard winter, he wouldn’t be able to pay back. Foreclosed upon in 1892, Wolcott became bitter and desperate. It was he who led the Invasion of Johnson County. A cattleman colleague described him as “a fire-eater, honest, clean, a rabid Republican with a complete absence of tact, very well educated and when you knew him a most delightful companion. Most people hated him, many feared him, a few loved him.” A neighbor said, “I never knew a man more universally detested.” Deputy Sheriff Malcolm Campbell described him as honest, “a polished gentleman,” and also a “bantam rooster,” and summed him up: “Wolcott was a man of very positive convictions, and his experiences with small ranchmen around his VR Ranch had often been of a violent nature.” Wolcott joined Edward David as one of the first commissioners of the new Converse County in 1888. He had also been, for four years, a justice of the peace. Campbell was elected deputy and was in office when Edward David took Carey’s men to push the Slichters out of their cabin.33

Years later, Campbell set down his record of the world Wister romanticized. He described “really vicious” criminals he had to deal with, but added, “there were many thousands of other cowboys who were loyally serving their employers, doing their daily duties willingly and well, and helping with the example of their fine, strong personalities, to build up the self-respect of the country.”34

Campbell felt, however, that the thousands of cattle on the range “offered a great inducement to cattle thieves, as the cattle were free and roamed for hundreds of miles, uncounted and untended. At the termination of most of the drives, the cowboys were paid off and left to shift for themselves. Many lost their money in the first gambling joints, and found themselves footloose in a land teeming with cattle which could with very little risk be driven away and sold.” And, Campbell said, after the cattle bust following the winter of 1886–1887, cattle stealing became a major problem, and he was frustrated by what he saw as the impossibility of getting local juries to convict for cattle theft.35

At the peak of the boom of the early 1880s, meanwhile, the big cattlemen—particularly the British—were, according to Campbell, “often arrogant, unfitted for the west and its demands, and careless of the country and its people. The cowboys in their employ knew them only with amusement, and there was built up then from the first a class contempt which was to reap its whirlwind in blood ten years later” in the Invasion of Johnson County.36

Campbell dictated all these memories at age ninety to Robert David, the son of Carey’s ranch superintendent Edward David. Robert, adopted from Chicago in 1897, lived in Douglas as a teenager. His father built a house in town where, in the World War I era, the family dressed in white tie and tails for dinner and were served by a Japanese cook. Small ranchers, like those Edward David had ousted from Box Elder, resettled and raised their families nearby. Robert married, clandestinely, “beneath him” into such a family, who ran sheep. He found that he could breathe easy in Douglas only after his father retired and moved several hundred miles away to Denver.37

Some 120 miles northwest of Box Elder Creek was Crazy Woman Creek, in the foothills of the Big Horn Mountains, about thirty miles south of Buffalo. The story of water rights there illustrates the impact of frontier Wyoming on Mead’s system, rather than the other way around.

Malcolm Campbell, down in Douglas, knew a wide stretch of the range. He counted “only two ranchmen of limited means on all the land between the Platte and the Missouri” in Montana—an area of several hundred square miles. Both those small ranchers were on Crazy Woman Creek. One was named John R. Smith. Smith did not like being pushed around on either land or water rights.38

Like Campbell, Smith was a former army freighter. Entering the Civil War at seventeen, he was a color-bearer for an Indiana regiment with Grant at the siege of Vicksburg. Immediately after the war, he came to Wyoming, went on a hunt with a portion of the Cheyenne tribe, got work as a freighter and a scout for the army, found a wife, and started a family of his own. He sent the family back home when the fights with the Sioux got hot in 1875–1876, and then he worked as a scout and freighter for the army. After that, he settled in. Using the Desert Land Act, he got title to land close to where Crazy Woman Creek intersected the Bozeman Trail on its route north from Fort Fetterman to Fort McKinney and the future town of Buffalo.

Crazy Woman is not a particularly generous stream. In its neighborhood, in fact, it’s the byword for dry. “If it’s dry anywhere, it’s dry on Crazy Woman,” say state water commissioners on the east of the Big Horns. Smith’s spot on the main stem of the creek, below the confluence of three tributaries, was probably the best place for water on Crazy Woman. His choice echoed the classic pattern of first settlers on Wyoming creeks: the earliest water rights, with the highest priority, are typically on the lowest, best spots, while later settlers make places for themselves upstream.39

Smith began digging irrigation ditches in 1878 to meet the requirements for getting title to the land under the Desert Land Act. He brought his wife and children to the ranch in 1879, cut native hay, and grew what vegetables he could (cabbage did best) for sale at the nearby trail crossing station and the fort. The territorial governor appointed him to help organize Johnson County in 1881. In 1888, he helped petition the legislature about the need for schools. The Smiths stuck it out and did all right—the family kept the ranch until the 1950s.40

As Campbell noted, however, Smith’s place was small, atypical in that portion of the Powder River Basin. Big cattle companies predominated. In May 1883, five years after Smith started his ranch, Crazy Woman Creek saw hundreds of cowboys and two miles of wagons in the big roundup of May 1883. Soon after, the forks of the creek in the hills up above the roundup were the setting of considerable water maneuvers—resulting in a tangle of water claims that long resisted straightening out under Mead’s system.41

In 1884, a big British-owned cattle company ordered its foreman to start focusing on “doing all we can to take up water” on the North Fork of Crazy Woman Creek—one of the small mountain basins above Smith. The company manager, Moreton Frewen, was a Brit, later known to his peers as “Mortal Ruin,” who had built what locals called a “castle” on the Powder River. Frewen said he was harried by new settlers “claim-jumping” on what he had regarded as his company’s range. He ordered his foreman to take up claims on whatever land and water he could.42

The ranch foreman was named Fred Hesse. He came from a middle-class British family, had once studied law, and wound up working for Frewen’s Powder River Cattle Company in Wyoming and running the big roundups on Crazy Woman in the early 1880s. Around 1885, Hesse made land and water claims, as Frewen ordered. One of his best friends did much the same, making water claims on the Little North Fork of Crazy Woman to form an irrigation company planning to sell water. Hesse’s friend was called Frank Canton. Born Josiah Horner, Canton changed his name after being convicted of bank robbery in Texas. Landing eventually in Wyoming, Canton fooled the people of Buffalo into electing him sheriff and the WSGA into naming him a stock detective in 1886. Hesse and Canton became infamous in northeast Wyoming a few years later as the local agents who helped fire up and guide the stockmen in the Invasion of Johnson County in 1892.43

In 1885, when Hesse and Canton filed on water, the Wyoming ranges were still in a “wet cycle” that made the land look lush. But the next year, 1886, brought the drought summer that preceded the famous bad winter. No one had been there long enough to have seen a drought. Getting by on Crazy Woman was tough. Smith wasn’t getting water, and he didn’t believe the problem was simply drought. He’d kept an eye on all the activity up above him: “They were all using it above me, and they were all taking it out,” he said, even though he had gotten there first.44

Coincidently, 1886 was also the first year of the territorial water law—probably intended to help livestock companies shore up their water claims—which called for people to file any water claim, new or old, in the county clerk’s office rather just in a notice posted beside the ditch. In Buffalo during that hot dry summer, all kinds of filings came in, usually testifying to a ditch-digging effort that had begun a year or two before. People seemed to have remarkable memories of the exact day on which they’d started to dig a couple of years before. The exact date would, after all, set the priority of their right. Their signed statements of claim were accompanied with reports on the dimension of their ditches. Smith, as well as Hesse and Canton and plenty of others, all filed papers declaring what day they had first dug their ditches along Crazy Woman.45

Smith didn’t get much more water in his ditches the next year, or the next, and by 1888, he was mad enough to go to court. Into Buffalo court files came Smith’s testimony and the records of all the considerable effort that had been put into water—or at least into water claims—by Hesse and Canton and others above Smith on Crazy Woman since the mid-1880s.

As it happened, the year 1888, when Smith went to court, was also Elwood Mead’s first summer as territorial engineer. Part of the law creating his job, after the disaster year of drought and blizzards, allowed people to ask the territorial engineer to measure their ditches. Smith, preparing his court case, had Mead survey the capacity of his ditches. The court didn’t require evidence on anything else—like how much land was actually watered by those ditches. Rather, as the law provided, the district court judge in Buffalo in 1889 set priorities according to the date and size of ditches and awarded the water rights by taking into account not only what people were actually irrigating but also what, in the official legal language, they “proposed” to irrigate. Proposals? Everyone on the creek had proposals. Lots of them. And proposals alone were the basis of the judge’s decree on Crazy Woman. That decree illustrated why Mead soon replaced district courts with a board of practical experts who could assess actual water use.46

Smith came out just fine, though, in the decree from the court in Buffalo. He got what he wanted—a big water right dated 1879, the best big water right on Crazy Woman Creek. Based on the size of his ditches, he got an award of water for 1,200 acres, the amount of land he “proposed” to irrigate. His claims weren’t even the most ambitious. Up and down the creek, people got awards of water rights aimed at irrigating amounts of land ranging from modest (150 acres) to preposterous (21,000 acres). The amounts of water that the judge awarded per acre, meanwhile, varied wildly, so the total of water rights had no logical connection to the acreage involved or to what the stream could provide. Canton and Hesse got rights awarded too, big ones, upstream. But their rights were established as junior to Smith’s. Smith’s was potentially the controlling water right on the creek; it gave his ranch one-fifth of the creek’s usual spring flows and all the water in the creek once the high spring flows went down.47

Smith had beaten Canton and Hesse in water. In return, Hesse soon took pains to label Smith as a rustler, thus ensuring that cattle Smith had shipped off to market would be seized as stolen goods. The label didn’t seem to stick well, however, on a man who everyone knew was a first settler, entrusted early on with public business in the county, and owner of a longstanding place everyone passed on the old trail heading to Buffalo.48

The Invasion of Johnson County started soon after, and soon the invaders were holed up, besieged, on a friendly ranch on the North Fork of Crazy Woman Creek. Characters from all around the range had taken part in the invasion, one way or another. Edward David, Carey’s foreman down in Douglas, cut telegraph lines so Buffalo wouldn’t know the invaders were coming; his neighbor Frank Wolcott had helped conceive the scheme and joined in leading it; acting Wyoming governor Amos Barber, who had been a much-trusted doctor at old Fort Fetterman, told militias around the state not to answer local sheriffs’ calls for help.49

Smith, on Crazy Woman, did what he could to hinder the invaders and bring the posse from Buffalo to arrest them. He also helped capture the invaders’ supply wagons, which, along with dynamite and many rounds of ammunition, contained the list of seventy men whom the invaders had targeted to be killed in Johnson County.50

Just a couple of months later, the air had cleared somewhat. Smith and others, once smeared by Hesse and Canton as rustlers, gathered and branded their cattle peacefully alongside the outfits of ranchers that had joined the invasion. But tensions and resentments lived on, and so did the 1889 court decree on Crazy Woman water rights. The decree was long impervious to Mead’s system, because the careful stream-wide adjudications by Mead’s board of practical experts could not, Wyoming courts said, touch water rights in a stream already covered by a decree made by a court, however nonsensical the outcome. Fortunately, there weren’t very many such decrees. And for a long time, people on Crazy Woman worked out a “good neighbor” agreement to ignore their decree, at least in terms of the volumes of water awarded. It seems that John R. Smith’s ranch, for instance, never did use all the water he had “proposed,” and so the other ranches got summer water.51

But in the 1970s, with the coming of the national energy crisis, water began to look valuable for power plants to burn Wyoming coal, and people on Crazy Woman started worrying that new owners of the old Smith ranch might try to sell the water right, which still looked so big on paper in the court decree, to an energy company.52 Their alarm made it clear that the water right decreed to Smith had not seen full use for years. People upstream were relying on using water that the ranch had never called for. They went to court.

Mead’s system finally came into play. The Board of Control—the practical experts—found a way to put its stamp on the old Crazy Woman court decree by “interpreting” it. That meant putting more realistic numbers on some of the rights prioritized in the decree, including officially allocating less water to the old Smith ranch. The board managed to banish the specter that had scared the neighbors—the possibility of the whole old Smith claim suddenly springing to life in new hands and completely disrupting everyone else’s water use on the creek.53

Still, water on Crazy Woman Creek continues sometimes to function in a world of its own. The board had to leave untouched the water rights held by people who hadn’t joined the complaint against the old Smith ranch rights. The best way to run the creek, therefore, has been by agreement rather than a legal list. Ideally, everyone would agree to take water under the per-acre standard that would have been in place with a stream-wide state adjudication. Calling in the state water commissioner would mean regulation of only some people under the old decree, with its odd, non-standard amounts. No one wanted that. So people on the creek were conditioned never to call on the state to resolve conflicts but to just rely on “self-help.” In summer 2002, self-help meant that one old man on Crazy Woman was collared by an upstream neighbor and intimidated out of using his water. Rather than complain, the old man put his place up for sale. The state water division superintendent knew what had happened and saw it as a characteristic of life on Crazy Woman. He didn’t interfere. He followed a long-standing practice of the water board Mead had established: unless a water user called for state help, it was not the place of the state to intervene.54

In fact, the self-help rule about water has prevailed all over Wyoming since before statehood and long after. It is the practice everywhere, not only the practice on the few creeks covered by old court decrees. Statewide, people can run water management on their creeks as they like, if no one complains. There is a sense that people should take care of their own water rights. Irrigators sometimes work out a way to rotate water use among themselves, with or without local state engineer’s office approval, particularly when water is short. Sometimes there’s a consensus agreement among neighbors, and sometimes there’s not. If things don’t go right, people have to muster the courage to speak up.

Before statehood, self-help was an official rule. Territorial law of 1886 said that officers in water administration should not intervene on a creek unless two owners on that creek asked them, in writing, to do so. That law stayed in place for a few years under Mead’s new system. But even after it went off the books, the principle was well established, reinforced by the vast spaces of Wyoming and the small size of state water staff. Modern Wyoming water commissioners typically still don’t step in to divide up water on a creek according to priority unless someone complains about not getting water. The current law says any one water user can ask a commissioner to step in, with a request in writing. On Crazy Woman in the 1880s, John R. Smith had certainly not been afraid to complain. But that isn’t always the case.55

The 1889 Crazy Woman decree captures, as if in a photograph, the world of the 1880s—its bravado, its pretensions, and its jostling for power among the likes of Fred Hesse and Frank Canton versus John R. Smith, somewhat like Joseph Carey and Edward David versus John Slichter on Box Elder.

Mead walked into that world with a dual role to play. The stockmen who brought him in, just after the disaster of 1886–1887, wanted both security and flexibility. They wanted to protect what they’d scrambled for, like claims on Crazy Woman. They also wanted an avenue to something new, since the drought and winter they’d just been through suggested that the open range business of the past was not the model for the future. The constitution and laws Mead wrote meanwhile were true to his beliefs, requiring him to “equally guard all the various interests involved.” That included the smaller farmers and ranchers, who wanted to find a foothold in Wyoming and help make the future.56

Mead offered a way to secure water claims, but only with scrutiny of water use. With that, he managed to provide both security and the flexibility to accommodate new people and new growth. His system could bestow a new imprimatur of legitimacy on existing water claims—but only after forcing those claims through a test. Old claims to water could make it into the new calf-bound, laboriously maintained state record books, inscribed as rights that the state would protect against all comers. But they would not necessarily be enshrined there in the size and shape of their progenitor’s fondest dreams. Mead believed that proof of actual use, of an amount of water actually necessary for the crop, was the narrow gateway through which the ambitions and dreams of a Carey or a Slichter, and ultimately of a Smith, should be forced to pass before they could get the protection that the new state system offered. That was the way to make things different from what they were under the old order as represented by the Crazy Woman decree.

Amid the ruins of an industry where paper cattle and dummy entry-men had been common currency and no one cared to ensure that grass or water would be there to serve a common future, Mead’s great feat was to give the state government the power to insist on evidence of genuine activity, produced by investment of cash, sweat, or both. On those terms, the state system would offer its protection to all, laying a foundation, in water at least, on which a new economy could perhaps be built.

The net result was that the small men were no longer necessarily dwarfed by the claims of the cattle companies. In the years following 1886–1887, despite the infamous drought and bad winter, more and more people came to try settling in Wyoming. They ignited the stockmen’s anger and fear that erupted in the Invasion of Johnson County. The pages of the histories compiled years later, the histories of Box Elder or Crazy Woman creeks, echo with the voices of the people who came, and kept coming, to take out a homestead claim all the way into the 1920s. Some cowboys or foremen from the 1880s made good with their own ranches; some emigrant families like the Slichters managed to keep going on small stock-farms; some settled their families on ranches that are still working today. In Laramie, a Norwegian sailor turned railroad worker found a Norwegian seamstress to marry and managed to buy a small ranch. Stories like theirs multiplied. Of course, people going for grandeur were still part of the picture. Carey worked to add to the Box Elder ranch. His son Robert listed the ranch, still called Careyhurst, as his residence when he became a US senator in the 1930s. John Kendrick, who had come to Wyoming in the 1880s as a cowboy, accumulated cattle and land near Sheridan (some of it by buying up the land allotment rights of Civil War veterans who never saw Wyoming; Carey did the same). Kendrick became a popular governor and then US senator. In 1915, when as governor he sat on the state land board, he added to his holdings nearly ten thousand acres of former state land controlling access to creeks near Sheridan.57

For all these people, Mead created a set of pragmatic rules for who could get what water in a dry, tough land, rules on which people could begin to build their lives. In the Wyoming that entered the twentieth century, some of the frontier persisted and left its traces on Mead’s water system—like the role that self-help retains on the creeks and how that shapes what water people really get to use. But a key Mead principle—the public supervision for overall public benefit, insisting on actual use of water—plus the structure of dedicated practical experts he put in place as supervisors, stayed in place and put their mark on Wyoming.