Excavation of Coolidge Canal, Wind River Indian Reservation. Courtesy of Edith Adams and WRIR Photographs, Randy Shaw Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

3. MAKING THEIR OWN WAY

Allow me to explain right here that the whole country is not farming land, but only along the margin of the streams.

—JOHN GORDON, DECEMBER 1881.1

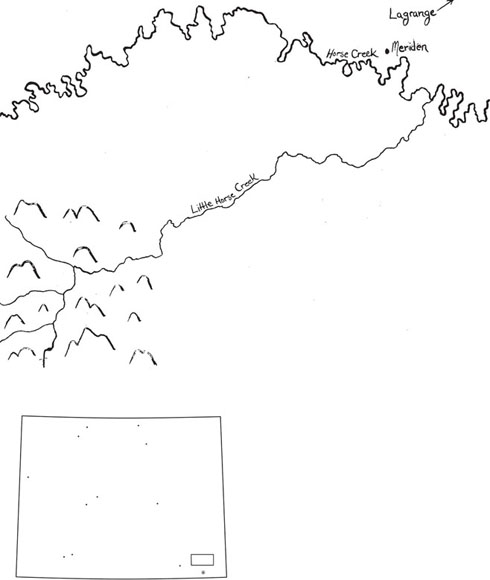

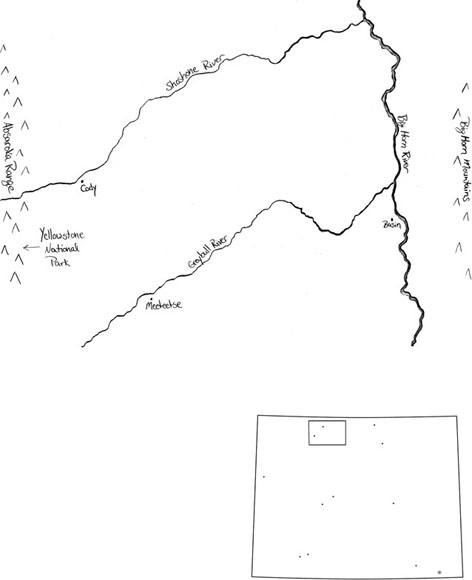

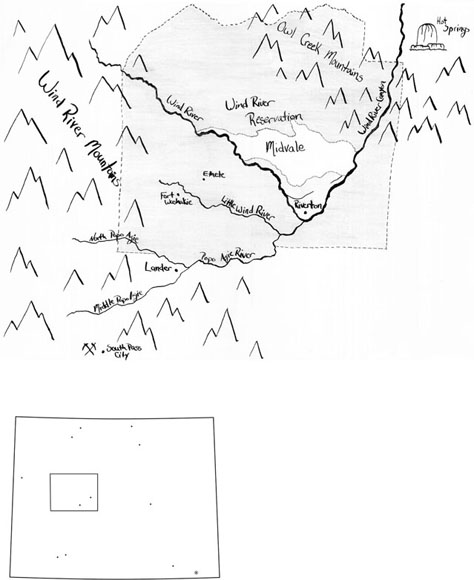

Places: Little Horse Creek, southeast Wyoming plains; Wind River, west-central Wyoming valley; Greybull and Shoshone Rivers, northwest Wyoming badlands.

Time: 1900–1920.

Excavation of Coolidge Canal, Wind River Indian Reservation. Courtesy of Edith Adams and WRIR Photographs, Randy Shaw Collection, American Heritage Center, University of Wyoming.

JOHN GORDON WAS IRISH, a fiddler who made his own violins. He came to the United States soon after the Civil War and was a carpenter in a Connecticut factory for several years. Then, with a Scottish friend he had met in the factory who was an avid reader of Horace Greeley’s newspaper and its call to “go West, young man,” he decided to try his luck in the West. He moved first to Greeley’s irrigation colony in Colorado and then in 1878, with his wife and three small children, moved to a cabin in southeast Wyoming. Three years after the family arrived in Wyoming, in December 1881, Gordon wrote to a cousin in Ireland who was thinking of following him. Gordon figured that man needed to understand how different Wyoming was from Ireland. He sent his warning: “The whole country is not farming land.”2

Elwood Mead, as state engineer, regularly told readers of his annual reports that with irrigation, Wyoming could become celebrated for agriculture. He soon agreed with Gordon that Wyoming would not boast farm products; rather, Wyoming would be known for raising prime stock fed on native pastures and hay or grain grown on irrigated bottomlands. Fifteen years after Gordon wrote to his cousin, Mead assured his readers:

A union of farming and stock raising is the form of agriculture best suited to our conditions. If . . . the arid uplands [were] utilized to supplement the irrigated valleys, one to furnish summer pasturage and the other the winter’s food supply, it would make Wyoming one of the most attractive and prosperous stock raising districts on this continent.3

But it turned out to be very hard even to transform strips of bottom land along the creeks into green hayfields; dry benches up above the big rivers might also someday be irrigated, but they were beyond the reach of individual efforts. Mead had told readers in his first annual report as state engineer in 1892 that major investment of capital would be needed for Wyoming to realize its potential through irrigation. Much of the North Platte river basin, where John Gordon and John Slichter lived, did not attract the number of settlers the way midwestern states did, Mead wrote. Bench land near old Fort Fetterman, for instance, “is not occupied, because as a rule, the pioneer is a poor man; the diversion of a great river is an undertaking he cannot compass. Until this is done the land has no value except for a grave, and is not attractive for that.”4

Men like Gordon and Slichter labored to make irrigated fields, in tough terrain, all over Wyoming. Their struggles, and the welcome Mead and Wyoming gave to federal investment in building water projects on the big rivers, had a good deal to do with what became of Mead’s water system.

In the first ten years of Mead’s system—from 1890 to the turn of the new century—Mead and his small staff worked on establishing the state government’s role as the gatekeeper for water rights, as demonstrated on Box Elder Creek and in Buffalo. They succeeded in convincing people of the principle that it was the state, not individuals, which would decide whether and how much of a water claim would persist with legal protection. Except in the case of water claims covered by troublesome territorial court decrees like the one on Crazy Woman Creek, water superintendents reviewed old claims for water rights from before statehood or new proposals made after 1890. They and the rest of Mead’s board would decide, after careful examination, whether an old claim could be recognized with state protection as a water right and how much water that right covered. In the case of a new plan to use water, it was solely the state engineer’s job to decide, after scrutinizing an application for its practicality, whether someone with a plan for water would get a permit as the first step to getting a water right.

But as the new century came on, new questions arose. Some of those were implicit in the water tangle that Gillette had cleared up with his adjudication in Buffalo. They became continually more pressing. Just what did you get when you were granted a Wyoming state “water right”? Was a water right something you could sell to someone else, somewhere else, to use the water as they liked? Was a water right something you could slowly make use of over time, maybe holding off for years before putting to use all the water involved? Did it depend on what kind of project you had, or what your neighbors thought?

Arriving at the answers to those questions involved considerable experimentation and debate. It took about twenty-five years, from 1900 to 1925, to work it all out, and the result was a considerable change from Mead’s original plan. While Mead had envisioned straightforward state ownership and control of water, set by experts working for the good of the people, by 1925, Wyoming’s water management system had moved in a different direction. Actions of the state water agency and the water users resulted in users joining the state agency as key decision makers. The agency and the users worked in symbiosis, acting as a community. The state remained the gatekeeper and recordkeeper but, as the history of Crazy Woman Creek suggests, the users—just as much as the agency—could set the rules for water use and help determine what enforcement occurs on an individual creek.

One reason that happened was simply the difficulty of enforcing Mead’s idea of state ownership and control over the vast and varied topography that is Wyoming. Mead had a small staff and often had to dig into his own pocket to pay for their travel. In 1898, he left for Washington to work on national irrigation policy. His successors, imbued with his ideas, continued to deal with small staff and huge distances. The result was that people on Wyoming creeks got to experiment. Wyoming terrain and climate, for that matter, required experiment; it was not obvious how to make irrigation work. Facing all kinds of obstacles, people gradually adjusted and changed the water rights system.5

John Gordon tried ranching in a couple of places in southeast Wyoming. His first spot, in the 1870s, was on the Laramie River, and there, as the cattle business grew, he began to keep his house as an inn on the road north. Judge Carey often stayed with him, and Gordon liked to say that he first pointed out to Carey the potential for watering the flat bench lands above the Laramie River. These lands became the irrigation colony that Carey and other cattlemen launched (joined by Gordon’s Scottish friend). They optimistically called the place Wheatland. In a peak year, before the disaster drought-summer and blizzard-winter, Gordon sold his own place in the area to some other big investors—who ended up among the Invaders of Johnson County eight years later.6

With money in his pocket, Gordon took his family on a pleasure trip back to Ireland and then brought them back to Wyoming to find another place to ranch. “We had decided we had enough roughing it on the frontier, and so looked at an old settled section on Little Horse Creek. I purchased three small settlers, and made an extensive ranch, built fine house and barn, refenced, reditched [sic] all the land, got all in fine shape to handle small bunch of fine cattle.” He called the place Springvale.7

In 1891, southeast Wyoming—known as part of Water Division I to the new State Engineer’s Office—was the most heavily populated area in the state. The superintendent of Division I was J. A. Johnston, the man who later judged the claims of Carey and Slichter on Box Elder. Johnston did his very first adjudication of water claims on Little Horse Creek, where Gordon had settled. There, a territorial court had started the work of sorting out water rights, but Johnston finished it. Little Horse Creek was indeed the “old settled section,” as Gordon had put it. It was near the capital, and water from the creek had been at work irrigating fields for some fifteen years. Reviewing the evidence Johnston gathered, the state engineer and all four division superintendents, meeting as the Board of Control, issued an adjudication in 1892 delineating the water rights (and commenting on the difficulty of the task). The adjudication confirmed that Gordon, based on the places he had bought from earlier settlers, held the earliest and best rights on the creek for his Springvale Ditch Company.8

Neighbors immediately challenged the board order. There were a lot of claims on Little Horse Creek—sixty-seven, in fact. Hoping to overturn the board’s decision, the holders of those claims went to court. As the case dragged on, Gordon eventually found himself in financial trouble—“I finally got enlarging myself too much,” he said—and sold his place. First, however, to bring in some cash and to appease the major opposition, he made a deal to sell a “half-interest” in one of his key water rights to a bigger neighboring ranch on the creek.9

Gordon sold his half-interest in a water right to an operation called Little Horse Creek Irrigating Company. It was headed by George Baxter, who invested in cattle after coming to Wyoming with the US Army as a young West Point graduate. Later, Baxter was appointed territorial governor (to F. E. Warren’s disgust), was ousted after forty-five days by President Grover Cleveland for illegal fencing but was elected to the Wyoming constitutional convention (where he argued for women’s voting rights). He competed unsuccessfully with Warren for governorship of the new state. Baxter had joined the challenge to the Little Horse adjudication just as he was heavily involved in the planning of the Invasion of Johnson County, and the subsequent successful legal defense of the Invaders.10

The deal Gordon soon cut with Baxter, however, said that Baxter’s Little Horse Irrigating could use Springvale’s water right, with its early priority, every other week—when Springvale was not using it. Baxter was satisfied, and with that water purchase he dropped out of the court fight over the Little Horse Creek adjudication.11

But there was a place on Little Horse Creek between Gordon’s lands and Baxter’s. It was owned by the James R. Johnstons (no documented relation to Division I superintendent J. A. Johnston), a solid and prosperous family with Little Horse Creek ranches dating from 1883. The family founders were two brothers from Ohio who had gone to California in the 1849 gold rush and were smart enough not to look for gold but to ride the gold boom as merchants and lumber dealers. After switching to stock raising, the Johnston brothers eventually came back to Wyoming, nearly forty years after they had passed through on the Overland Trail. Settling on Little Horse Creek, they had extensive cattle, horse, and sheep herds. Characterizing themselves as people of “pluck, perseverance, and integrity,” they were disturbed by the Gordon-Baxter deal. Not only did they have a ranch between Gordon and Baxter, but some of their water rights were between Gordon’s and Baxter’s in priority. Those water rights would get less water because of the Gordon-Baxter water sales contract. The Johnstons went to court to fight the water sale.12

In settling Little Horse Creek, people had inevitably developed a pattern of water use. Gordon’s water rights, attached to the lands he bought from earlier settlers, amounted to 10 cfs; he had been diverting that much for irrigation every other week in the summer. The plan under the Gordon-Baxter deal was that Gordon would keep using his 10 cfs as always, but Baxter’s company would use 10 cfs in the off-weeks, that is, every second week all summer.

Before the deal, when Gordon didn’t use his water in the off-weeks, more water had been available for the in-between junior water right holder—the Johnstons. But with the Gordon-Baxter water sale, that water would no longer be available to them.13

On paper, Gordon had simply sold off half of his water right. But in effect, the Gordon-Baxter sale doubled the amount of water used under Gordon’s high-priority right. Gordon’s neighbors, the Johnstons, were outraged, and the State Engineer’s Office was horrified. It was a classic example of what Mead had sought to prevent. The water commissioner at work on Little Horse Creek refused to honor the contract between Gordon and Baxter. The Johnstons meanwhile asked the courts—still reviewing the board’s adjudication of the creek—to defeat the water sale contract. As the Johnstons and the engineers saw it, Gordon had sold off something he had never used and therefore never had. The Board of Control refused to recognize the sale.14

The Laramie County District Court overruled that board decision. The court held the sale valid and described a right to use water as a property right that could be sold like any other property. The Johnstons appealed to the Wyoming Supreme Court. While the high court decision was pending, Mead, no longer in Wyoming, was disturbed to see the district court ignore the tie of water to land that he believed was fundamental to the water law he had written. He wrote bitterly of the implications of the district court ruling:

It is not believed . . . that (the district court opinion) will be sustained by the supreme court. If it is, water rights acquired during the Territorial period will become personal property. The water of the public streams will become a form of merchandise, and limitations to beneficial use a mere legal fiction. If water is to be so bartered and sold, then the public should not give streams away, but should auction them off to the highest bidder.15

The Wyoming Supreme Court ruled in 1904 to uphold the Gordon-Baxter water sale. Chief Justice Charles Potter wrote the court’s opinion. He was the man who had worked with Mead on the water language in the constitution and just four years earlier had so deftly and stalwartly upheld the overall water management system in the Buffalo case. When it came to the question of selling off a water right, however, Potter parted ways with Mead. He thought it was a matter of course that water rights could be sold to a new location.16

Potter’s decision landed like a bombshell on the State Engineer’s Office. Superintendents of the water basins protested in public reports. Mead wrote ever more bitterly, saying that allowing a water sale like the Gordon-Baxter deal meant the court was dragging Wyoming down to the level of other western states, with the laws he believed “belong to the lower Silurian period.”17

Potter saw the situation as a relatively simple one. He interpreted Gordon’s 10 cfs water right as a right to 10 cfs of continuous use all summer—just the way it looked on paper. The irrigators, the State Engineer’s Office, and Mead had pointed to the pattern of actual use of that 10 cfs of water—only every other week—and urged that the pattern of actual use determined the water right and should be protected. Potter did not grasp that, though. Taking the water right at face value as it stood on paper, the chief justice said that half such a right could be sold off the land and used elsewhere.18 Potter’s judgment made reality of Mead’s nightmare—water being “bartered and sold,” like any other kind of property. The portion of a water right that Gordon had sold could be used elsewhere. The Wyoming legislature deferentially followed the court ruling, enacting a statute allowing water transfers away from the original land.19

But the high court’s decision and that new statute did not last long. Water users and the State Engineer’s Office soon managed to overturn it. In 1905, the state engineer was Clarence Johnston, son of J. A. Johnston, who had been Division I superintendent. Mead had brought young Johnston on staff in the 1890s and taken him to Washington for a few years. Back in Wyoming as state engineer, Clarence Johnston convinced the legislature to appoint a special commission on water law, with himself as a member.20

Johnston was sometimes regarded by later members of the State Engineer’s Office as someone who could overstate facts with a flourish—“Oh, Clarence!” members of the Board of Control would say, as late as the year 2000, when they found errors in water permits he had signed. But he was dedicated to upholding Mead’s water law. The new water law commission, with Johnston on board, took the unusual move of sending out written surveys to water users statewide. The survey revealed user views on a variety of topics, including support for the common practice of rotating water use on a creek in times of shortage, allowed generally by territorial law, to be officially recognized with rules set by state engineer staff. Most important for the Little Horse Creek case, a strong majority of users responding to the survey opposed water sales. The commission convinced the legislature to enact new laws in 1909, adopting the users’ views on issues like rotation and, most significantly, overturning the Little Horse Creek court decision. The key new law explicitly forbade the sale of water rights to use on other lands, on pain of loss of priority—and losing priority, of course, meant in effect losing the water right. A companion statute set an exception, so water for towns or other “preferred uses” could be changed from their original uses, paid for, and moved to the new use, without loss of the priority date.21

The new law meant that the options of someone who had a Wyoming water right had limits that were very clearly stated. Water rights generally could not be sold away from their setting; irrigation rights, for instance, could be sold only along with the land, except for the special case of a “preferred use” buyer, like a town. And what a water right consisted of was limited. The new law specifically provided that a water right held by anyone in Wyoming was defined by the actual characteristics of water use—how much water was necessary and used for what purpose, on what lands. “Beneficial use shall be the basis, the measure and the limit of the right to use water at all times,” the statute read, and is still the law today.22

State engineer Johnston saw this statute he had helped draft as a fundamental step in clarifying the limits of a Wyoming water right—the limits that he, his predecessors, and the Board of Control had consistently applied. He laid out all the details of what it meant in a triumphant essay titled “What is a Water Right?,” published in his 1910 public report after the struggle was over. The key principle, he wrote, was that the needs of the public and the community on a stream must prevail over the desires of an individual. The pattern of water use on which a community had been built and daily relied on should not be disrupted; even a town, a “preferred use,” could obtain only from an irrigator, for instance, a right to the volume and timing of water that the irrigator had employed. The proper idea, Johnston wrote, was to “afford protection to every claimant yet . . . no man is given a weapon whereby he may destroy the prosperity of his neighbors. All that need be borne in mind is that the right to use water should be limited in accordance with the beneficial use made and the right should belong to that use rather than to the user.”23

Baxter, the former governor who had bought water from Gordon, got to keep the right to that water as a result of Potter’s ruling. Still, he must have been chagrined to see the general concept of water sales defeated for the future by the voices of other users. He, and likely his peers, wanted a straightforward rule allowing water transfers so someone with a water right could sell water to a new location—to anyone else who could find a use for it, wherever that use might be. Yet the idea didn’t stick in Wyoming that individuals could own water as private property that could be moved, bought, and sold. The reverse happened. Wyoming wound up with a statute firmly stating the principle Mead had intended to be part of the original water law. Baxter and the high court had run into not only the strong beliefs about water in the State Engineer’s Office, but also the on-the-ground experience of Wyoming water users. Experience told users that water was something different than land.

Mead’s successors in the engineer’s office were men he had trained and so imbued with his views that they can fairly be called his disciples. They believed what he believed: that allowing an “absolute property right in water” would encourage speculation that would destroy orderly water use and people’s efforts to build settled communities.24

Little Horse Creek, a small stream, had fostered just that kind of community. The people living along it came to know their creek, their soils, their climate, and each other well. They found out how much each one’s water use was tied to what others did along the creek. Water users around the state also heard of the deal Baxter had cut with Gordon, as the case went through the courts and the state engineers’ reports highlighted it in outrage; people could talk it all out with each other and with the water superintendents, who felt passionately about it. Enough time passed for water users and superintendents to unite in a new understanding: that people working with a limited water resource were interdependent in a way peculiar to people living in arid regions. Water, in a place like Wyoming, could not be thought about in the same way as land.25

When Edward Gillette was superintendent in northeast Wyoming back in 1896, he wrote about what that notion meant on the ground. A dry year, he said, meant “intense feeling, theory and pet laws for the government of water are cast aside. The condition is an angry farmer, the half-matured crops on his land, which gave promise of an abundant harvest, are rapidly burning up.” An irrigator had to be stopped from simply moving water wherever he wanted, Gillette wrote. “No other determination would long be tolerated by his neighbors.”26

Justice Potter wrote in 1904 that to disallow the Gordon-Baxter sale would be “to deny the element of property in the water right itself.” That he refused to do. But the water users and the engineer’s office, followed by the legislature, went right ahead to do just that. They denied “the element of property.” They saw water as so different from land that they had to try something new and make new rules.27

As Mead told national readers in 1902, when the Baxter-Gordon contract was heading to the Wyoming Supreme Court, people who worked with water often saw things differently from lawyers and courts. The legal system was all too likely to apply to water the rules about ownership of private property in land:

The speculative value of the personal ownership of running water is so great that every argument which the ingenuity and intellect of the best legal talent of the West can produce has been presented to the courts in its favor. Organized selfishness is more potent than unorganized consideration for the public interests.28

The two figures in the saga of “organized selfishness” that had played out in Wyoming met different fates. George Baxter retreated to his native Tennessee, where his wife had come from a wealthy family. He had had a moment of fame in the society pages “from coast to coast” in 1900, when his daughter left her Denver fiancée waiting in church and ran off to marry a much older “wealthy socialite” in San Francisco. After John Gordon sold Springvale, he moved to Cheyenne and ran an experiment farm for the state’s Department of Agriculture. As an old man, with a penchant for reciting Robert Burns, he moved to California to live with his daughter’s family, and there at last he wrote, “I have a garden which I love to cultivate and make plants of all kinds grow to perfection.”29

Most water users in Wyoming were more like Gordon and his Johnston neighbors than Baxter. They were small ranchers and farmers, and they had a personal relationship with their superintendents that was significant in shaping policy. The superintendent in Division III, northwest Wyoming (the basin of the Shoshone and Wind-Big Horn Rivers) wrote about that in 1910:

The people are coming every day for advice and information that they can get in no other place. In this respect, it is one of the most important positions in the State. It deals more directly with the people, knows their needs and conditions better than any other place, and is of the greatest help to them, all of which they fully appreciate. In connection herewith I want to express my appreciation of the help and good will extended to me by the people. They have given me every encouragement in the performance of my duties and without their hearty co-operation the administration of the work of this office would be extremely difficult. They have always been consulted before any great change has been made and their advice has always been good, founded as it is, upon actual experience and observation.30

There was more water policy ahead to be made by the state engineer, the superintendents, and the water users. By 1910, some questions had been settled: the state water office, representing the public, would determine who got what water right, whether by investigating old claims or issuing permits for new ones; and once a person had a water right, it was defined by its use, and in general, he could not sell it away from the place or purpose for which it was used. Just a few years later, the high court affirmed the State Engineer’s power to limit, in a new permit, the size of a proposed hydropower dam to accommodate the future value to the public of the only practical railroad route to connect northwest Wyoming’s Big Horn basin to the rest of the state.31

But it was not yet obvious how soon a person with a state water permit once in hand must put the water to use. And that was a question with major implications. Could you hold off, wait some years to put the water to use, but still end up with a water right for the volume of water you first envisioned, dated when you received the permit—with that valuable priority date, so that you could always get that water before someone who got their permit later?

The State Engineer’s Office believed the answer to that question was clear: absolutely not. To acquire a water right, there were many obligations to meet. Obtaining a permit was merely the first step toward securing a water right. To get a valid right to use water, the next step was to put to actual use, and in a timely manner, the water for whose use the state had given merely an initial permit. Under the water laws of 1890 that Mead wrote for Wyoming, state water permits had requirements written into them, clear deadlines for the start and finish of water facility construction, and for getting water into actual use (with irrigation, that meant onto the land). After water had reached farm fields and proof of the water use matching the permit was presented to the local superintendent, he was to inspect. If he could verify that the water was truly in use, the Board of Control would issue a “certificate of appropriation.” That certificate was what conferred a valid water right, and it would be a right for only the amount of water the inspection showed was being used.32

Successive state engineers all shared the same view: a water permit once issued should be regarded only as a contract with the state. That contract merely gave a would-be user his opportunity to put water to use—under certain conditions, including firm deadlines. Only compliance with all the contract conditions, including deadlines, would result in someone’s obtaining an actual right to water. The penalty for failing to comply on time was severe: the permit and the opportunity for a water right with priority position would be canceled. State Engineer Johnston, trained by Mead, put it this way in 1904: “If the applicant does not sufficiently appreciate the value of the water right sought to comply with terms of the permit, it should be canceled in order that others who have shown proper diligence may be protected.”33

It was a matter of basic policy. The concern was fundamentally the same as in the water sales debate on Little Horse Creek. To allow applicants to proclaim themselves “users” by obtaining a state water permit but doing nothing more was to allow speculators to obtain Wyoming water rights and potentially hamper the growth of self-supporting settlements. Further, the growth of prosperous communities demanded that unsuccessful ideas make way for new, more promising proposals. That again meant that no one should be able to obtain a state permit, fail to use the water, but keep the permit and a claim to the water. If someone could do that, he could create for himself the ability to bide his time and keep the permit priority date, preempting others who could put the water to use right away.

Mead, early in implementing the state water system, had after all pointed out that sometimes he would issue a new permit, with a new date, to irrigate lands already covered by an earlier permit. He would do that if it appeared that the holders of the initial permit simply weren’t progressing with their project. Mead informed one laggard permit holder that “the fact that you have had a year of unrestricted opportunity with no visible result, as I am informed” meant it was more important to the state of Wyoming to issue a new permit to someone with new plans than “that development should be retarded in order to protect your prospective profits.” Mead similarly warned Judge Carey’s Wheatland project that it would lose water right priority to later users, in adjudication, if project lands didn’t use the water claimed in 1883.34

Mead had a similar goal when his state water-law code adopted the rule in Wyoming Territory—the standard rule in prior appropriation law—that even a water right with a certificate of appropriation could be lost if it were not used. A water right could be challenged and lost, considered “abandoned,” if it could be proved that the water involved had not been used for a few years. In Mead’s mind, water rights had to be placed in the hands of people who proved successful, in order to put Wyoming water to use quickly, keep it in use, and build communities in arid country.35

But, put Wyoming water to use quickly? Putting Wyoming water to use if possible turned out to be the more practical goal. In the end, in fact, that turned out to be so hard to accomplish that a Wyoming water permit came to mean something quite different from what Mead and the early engineers who followed him had imagined. A series of events in the first twenty years of the twentieth century led to that outcome. These events unfolded in a place that reeked of impossibility—a very different part of the state from Little Horse Creek. That place was the Big Horn basin of northwestern Wyoming, adjacent to Yellowstone National Park.

Yellowstone’s wild landscape had been consecrated in the 1870s as the first national park, and it had attracted well-heeled eastern visitors and the construction of luxury hotels. Nonetheless, the Big Horn basin, east of the park’s boundaries, remained frontier country in 1902. Isolated by physical barriers from more settled parts of the state, the region had the harshest terrain, sparsest population (less than five thousand, or about one person for every three square miles), least economic activity, and least social stability in Wyoming.36

The Big Horn basin also had in spades what any newcomer who tried irrigation found almost everywhere in Wyoming. Whether armed with cash or with just a mule and a scraper, everyone—including the state engineer and his staff—met surprises trying to put their ideas about water into practice. They were all profoundly ignorant of the land and climate in which they were working. The people before them, who had moved through there for thousands of years, had not seen it as a place to grow crops. The new inhabitants, coming from farming country, joined Mead in envisioning profitable agriculture—some even imagined row crops, in addition to the hay that eventually dominated most irrigated fields in Wyoming. The new people had little idea what would be required in finances and engineering to irrigate the terrain or to grow crops at elevation. They faced a steep and painful learning curve. Many private irrigation ventures died.37

The Big Horn basin was the home of the superintendent who wrote in 1910 about the importance of responding to the “actual experience and observation” of water users.38 Mead described the basin in 1898, just before he left the state, as:

An immense bowl entirely surrounded by lofty mountains. It has not, however, the appearance of a valley as that term is ordinarily used. The greater part of the surface is hilly and broken. Some of the bad-land ridges rise almost to the dignity of mountains and present a picture of aridity and desolation which disappoints and discourages many of those who visit this section for the first time. None of the broken country can be reclaimed. The limits of irrigation are restricted to the bottoms and table-lands which border the water courses. Outside of this the country is neither adapted to the construction of ditches nor fit for cultivation even if water could be carried to it.39

Nonetheless, there seemed no end to big ideas for testing the “limits of irrigation” in the Big Horn basin. Some dreamers brought money, some brought know-how, and some brought neither. One with money had the fine name of Solon Wiley, with a career behind him as a public-utility engineer in Omaha. Starting in 1895, he formed a company and obtained Wyoming water permits for a plan to build an irrigation colony on flat bench land above the Gray Bull (now the Greybull) River, a sizable stream that heads up in high mountains and had for some time watered ranch lands in pleasant foothill valleys before it crossed the more desolate country that Wiley hoped to make bloom. Wiley’s permits included both a new permit, dated 1896, and some old permits he bought, dated 1893, which had been issued for a project on the bench land envisioned by Andrew Gilchrist, the Scot with whom Gordon had emigrated West. Gilchrist had become a major figure in Wyoming, acquiring significant ranch lands and a major share in the Stock Growers’ National Bank. He died, however, before he could do anything with his idea for a Gray Bull project.40

Wiley also got federal public lands set aside for his project, under a new law to help water projects, a law Judge Carey, in his last year as US senator, authored in consultation with Mead. The Carey Act, enacted by Congress in 1894, was intended to boost the chances of success for private irrigation developments. The idea was to let state governments set up contracts with private developers so the states would supervise major irrigation projects to which federal lands would be allocated. Those “Carey Act lands” would be “segregated” from the general public lands for project use only—they couldn’t be homesteaded or otherwise claimed by others while the state-approved project was getting underway.41

Wiley took up the Carey Act challenge, came to the state, accepted state supervision, and got federal lands designated for his irrigation project. He was not an absentee entrepreneur but a very hands-on one. He personally supervised construction of his canal, and his wife cooked for the laboring crews. But the planned network of ditches was ambitious, and progress was very slow. It looked like Wiley might not meet the construction deadline in his state water permits—a deadline of the last day of 1902.42

As his canals began to reach some of his lands, however, in 1901–1902, Wiley wanted water for the few farmers he had convinced to settle there already. A major drought had struck in 1902, one of the worst many Wyoming settlers had ever seen. Wiley got into an argument with downstream neighbors using the Farmer’s Canal, a group of experienced Mormon irrigators who had figured out how to farm formerly desolate lands and had a state certificate for their water right. Their priority date was 1894. Wiley, who had gotten a state water permit for his venture only in 1896, nonetheless claimed an 1893 date for priority to take water from the river, based on the 1893 permits he had bought up. Those permits had contemplated watering the lands now beginning to be reached by Wiley’s canals. So now Wiley believed the date of those permits had become valuable.43

Back in 1895–1896, when Wiley started his project, Mead was state engineer in Wyoming. Mead had issued a new permit for Wiley’s more ambitious project to water the lands covered by the old 1893 permits, under which no land had yet been watered. Consistent with his policy of encouraging the new, Mead had issued a new permit in 1896 to cover substantially the same lands as the 1893 permits. The new permit had the 1902 construction deadline. As he recalled later, Mead also made it clear to Wiley that his was a new project and could get no earlier priority date than his filing of 1896; the old permits Wiley had acquired would not give him an earlier priority.44

Now, in 1901 and 1902, as Wiley argued with the Farmer’s Canal and claimed 1893 priority for getting water, Fred Bond, Mead’s successor as state engineer, had to decide what to do. The problem was Wiley’s proposal to take water in a priority earlier than the Farmer’s Canal. Bond appreciated Wiley’s construction difficulties, which meant the looming 1902 deadline set by Wiley’s 1896 permit was not likely to be met. He also had some sympathy for the eager farmers at Wiley’s colony, who were living in sod huts, waiting for water in drought, hoping to raise a crop and maybe build a cabin. The engineer was totally unwilling, however, to give Wiley’s project any priority over the Farmer’s Canal, where the farmers were equally or more deserving. They had worked hard and successfully watered the land and “proved up on” their water right, getting it officially adjudicated.45

The state engineer asked for advice—twice—from the state attorney general. He did not, however, get the answer he wanted. The attorney general insisted that Wiley should indeed get water with the 1893 priority position he sought, ahead of the Mormon colony. The attorney general also went further and said an unmet construction deadline on Wiley’s project would be no problem and should not affect his permit or his priority right to water, whenever he did get everything built and settled.46

This attorney general was an interesting character, quite an obstacle for state engineer Bond to encounter. Named Josiah Van Orsdel, he had come to Wyoming from Pennsylvania in about 1892 and was a lawyer for another Big Horn basin promoter. He knew Mead, because that promoter had had Mead survey his irrigation project plans. Van Orsdel eventually became head of the Wyoming Republican Party, succeeding to the position earlier held by Willis Van Devanter, who had been Warren’s right-hand man. Then Van Orsdel was appointed as the state’s fourth attorney general, a post he filled for seven years, longer than anyone before him. In 1905, he became briefly a Wyoming Supreme Court justice, and then, like Van Devanter, went on to legal work in Washington, first as an assistant US attorney general and then as a judge on the federal court of appeals there.47

The first problem State Engineer Bond presented to Van Orsdel was whether water should be delivered to land still being developed under a water permit in a river already in heavy use. When other users wanted the water, had their rights adjudicated, but had a later priority date than the permit claimed for the partially developed project, did that project get some water first? Van Orsdel responded, quite naturally, that someone with a water permit who was working to put water to work under it had to be able to get water under the permit priority date, ahead of others’ later rights, in order to have a chance of meeting deadlines for getting the water put to use. In any given irrigation season, he said, it was up to the local water commissioner to decide how much land was truly ready for irrigation under the permit and so how much water should be delivered under the permit.48

Van Orsdel accompanied that statement with a rather expansive new view of water rights in Wyoming, declaring that state water permits were much more than Mead or his successor believed. State water permits should, he said, be regarded as documents that conveyed a germ of a property right (an “inchoate” right, he called it). The permit holder had obligations: to nurture the right by putting the water to use. The State Engineer’s Office, however, also had obligations: to protect that right at the earliest stages, which could require delivering water before construction was complete. Van Orsdel noted that questions about delivering water to land still being developed, to the detriment of later-date water holders, wouldn’t come up very often in the case of small plots of land that individuals could develop in a timely fashion. But it would and had come up, he said, in the situation of a big project like Wiley’s, where getting settlers and water on the land would be a lengthy process.49

The problem was that the Farmer’s Canal adjudicated rights were not later but earlier than Wiley’s 1896 permit from Mead. Farmer’s Canal had priority over that permit. Wiley’s demand for water had a major hitch: the only permits he had of an earlier priority date were the 1893 permits that had never been used. In 1902, Bond asked again, with more urgency, for legal advice on Gray Bull River water, highlighting that the basis of Wiley’s claim was those 1893 permits so long unused. Van Orsdel responded by expanding on what an “inchoate water right” meant. The “inchoate” rights received under a Wyoming water permit couldn’t be canceled by the State Engineer’s Office—only the Board of Control could do that, if the water user sought to show that water was used, in the adjudication of his water right. The germ of a property right granted in a Wyoming water permit gave a permit holder not only the right to use water but also the right to change plans for reaching the same lands with water, he said. If someone like Wiley, with a new plan, bought up older permits, he was merely changing old plans and could claim the old permits’ priority date. The 1896 permit Mead gave Wiley had been for the same amount of water and land as under the old permits. It should be viewed as just an extension of time, to the end of 1902, for the water to be put to use under the 1893 permits and their priority date.50

Van Orsdel went further: water projects like Wiley’s were a special case for Wyoming’s water office. Under the Carey Act, developers such as Wiley got federal lands set aside for irrigation projects that the state approved and provided with water permits. The state had to certify that enough water was available for the project. State law implementing the Carey Act had declared that water certified as sufficient for the project would go to the lands set aside for the project. And a big project could take years to develop. Given the probably long time until project completion, it was only logical that “sufficient water must be reserved at all times to irrigate the lands segregated.” No matter how long it took to build the project’s irrigation canals, the state couldn’t turn around and give priority to subsequent water rights, just because the water reserved for the Carey Act project had not yet been used. Wiley need not worry about the December 31, 1902, construction deadline; the construction deadline in the state water permit simply could have no force for a Carey Act project.51

Van Orsdel’s conclusions caused an uproar—along the Gray Bull River, in the State Engineer’s Office in the capital, and beyond. Van Orsdel had said that Wiley’s project should get water ahead of the Mormon farmers, no matter how long it took Wiley to get the project going. People were outraged. Van Orsdel wrote to Mead about it. Mead was now heading up the Division of Irrigation Investigations for the federal Department of Agriculture in Washington, DC. From Washington, Mead told Van Orsdel he recalled the sequence of permits involved in the Wiley project and the Farmer’s Canal very well. He declared flatly that Van Orsdel was wrong. Van Orsdel’s pronouncements, Mead wrote, “would cause unending confusion, would be unjust to other appropriators on the stream,” and, overall, violated the Wyoming constitutional language on water that Mead had spearheaded. Mead similarly dismissed Van Orsdel’s view that the Wyoming statute accepting the Carey Act negated state water permit deadlines. Mead had been one of the people drafting that statute. Van Orsdel responded doggedly that he knew that his view was contrary to that of everyone involved in Wyoming’s acceptance of the Carey Act, but he believed his view would prevail in court. And as for his interpretation of the “inchoate” rights conveyed under Wyoming water permits, Van Orsdel concluded, “I am aware that I have departed from some of the principles upon which we were always agreed, in my opinion, but I still believe that my opinion to a large extent, will be upheld.”52

Van Orsdel’s prediction was both right and wrong. Initially, the State Engineer’s Office had little choice but to implement the attorney general’s opinion and give Wiley water. The Farmer’s Canal immediately filed suit, represented by another Cheyenne lawyer who had been both a Wyoming Supreme Court justice and US attorney for Wyoming, a prominent Democrat challenging the arguments of prominent Republican Van Orsdel. The state district court ruled for Farmer’s Canal, and against Wiley—overruling Van Orsdel’s opinion. The district judge said Wiley could get some of the water he needed—but only after the Farmer’s Canal got all its water. The court ruling stuck. Both projects on the Gray Bull were successfully irrigated under that order of priority for decades to come (and they eventually worked together to get reservoirs built on the river to improve water deliveries to both). The State Engineer’s Office, meanwhile, gave settlers under Wiley’s project extension after extension, into the 1950s, to get the water onto the ground.53

All this was, however, only an initial wrangle over what was involved, what had to be done, to acquire a protected priority right to water in Wyoming. There was more to come—and Van Orsdel’s thinking in the Wiley case managed, through various twists, to have an impact where it mattered: in future policy, nationally and in Wyoming.

The turn of the century was a time of considerable turmoil and significant action in national policy affecting the West. The pressure of a growing population in the industrialized East merged with western aspirations for more land settlement and agricultural production and together produced new national policy. In 1902, just two weeks before Van Orsdel sent his advice on the Wiley case to the state engineer, Congress had passed the National Reclamation Act. It made its way through Congress with considerable fanfare and controversy, with Wyoming’s delegation—first Senator Warren, then Congressman Frank Mondell—much in the fray. The new law provided for federal construction and maintenance of major dams and irrigation works across the West. Mead, with Warren’s ear, had pushed for a more state-centered program, but that idea lost out. Mondell, whom Mead privately considered ignorant about irrigation—“opinionated and somewhat bumptious”—pushed the successful language for expansive federal involvement in irrigation that President Theodore Roosevelt wanted. Promotion of the final Reclamation Act played on the widespread recognition that private ventures had proven incapable of taking on the big projects, and the belief that not only the West but the nation would benefit greatly from irrigation to create small western family farms, producing solid citizens along with fruit, vegetables, and grains. Agriculture was seen in the nineteenth century as the universal first step in development of “civilized” societies, and the ideal of the small family farm, however inappropriate to the topography and climate of the West, drove policy, investment, and boosterism well into the twentieth century. The passage of the Reclamation Act was watched closely in Wyoming. The years ahead showed what faith in farms might mean for people on the ground there.54

The turn of the twentieth century also produced a congressional consensus for an increasingly hard-headed approach to a fundamental social issue in the West—the relations between the native people and the whites who now dominated the region. Initially, national policy attempted to keep the two very different groups apart. Surviving members of native peoples in the East had been forced West in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; mid-nineteenth-century treaties with native peoples in the West had typically, as on Wind River, reserved large tracts of land to tribes while “opening” to settlement certain lands that the tribes formally agreed to relinquish. But as white settlers kept pushing into the tribes’ lands—seeking land or gold, massacring buffalo, and bringing on the army—the tribes became, in the national mind, a defeated former enemy to be handled by special policy. As historian Frederick Hoxie describes it, in a close study of federal Indian policy, 1880s policy became “assimilation.” On land previously held by the federal government for the tribes in communal ownership, native people should become private landowners and family farmers. Their children would be educated to a white Christian model (hence the infamous shipment of children to a harsh life, and sometimes death, at boarding schools far from home). In a generation, they would be “civilized” according to the standards of their conquerors, perhaps becoming professionals as well as farmers, mingling with the rest of the population in the pursuit of happiness extolled by Jefferson as the right of all men.55

The idea that agriculture was an appropriate occupation for native peoples had been a feature of many mid-century treaties like the one in 1868 creating the Wind River Reservation for the Eastern Shoshone. Farming became the official national goal for native people in the 1880s, to be accomplished by allotting to individuals, once they were deemed “competent,” small plots of private property in the original reservations. It was a policy originally intended to be benign, to bring on “civilization” on the white model. No magical transformation of native people into farmers occurred, however. By the turn of the century, the assimilation goals of Congress and the Department of Interior supervising reservations hardened, sanctioned by the US Supreme Court, into what another historian describes as a “coercive and vicious” policy: native people were to be put onto their own small farms, ready or not; the “surplus” land in those nineteenth century reservations was to be taken and opened to new non-native settlers; and native families, now considered capable only of rudimentary education and manual labor, could just learn to survive in the school of hard knocks.

Wyoming congressman Mondell embodied that policy in the late 1890s. He had arrived in Wyoming in the late 1880s at the age of twenty-seven, helping to open coal mining in the northeast of the state in the wake of Gillette’s rail survey. After being elected to Congress in 1898, he promoted manual training for native children, to teach them “how to perform the work they would be called upon to do, particularly in housekeeping and agriculture, after they left school.”56

Historian and Wind River area rancher Molly Hoopengarner and geographer Paul Wilson have traced in detail what that policy did in agriculture and water use on the Wind River. Federal negotiations with the Shoshone and Arapaho on the Wind River Reservation began soon after Congress passed the 1887 Allotment Act aimed at putting native families onto surveyed lots and selling “surplus” lands to new settlers. The tribes’ people were starving as the term of the annuities promised by the 1868 treaties was running out. After years of talks, the tribes sold, for cash and cattle, ten square miles of a hot springs area in the north of the reservation in 1897. Mondell made that happen, and the same year, he pushed for new surveys “with a view of preparing for the cession of a portion of the Wind River Reservation later,” as he put it. He saw the Wind River as a “fair and fertile region,” and he wanted a large area north of the Wind River opened to settlers. He also noted that the Department of Interior was slowly making allotments there for native families, “evidently with the view of justifying a grandiose Indian irrigation plan.” He and Warren accordingly got the allotment process speeded up—and restricted mostly to the south side of the river—while pushing for more land cession from north of Wind River despite opposition in both Interior and Congress.57

By 1904, though the reservation’s agricultural economy had begun to improve, with people hand-digging their irrigation ditches, the Shoshone and Arapaho leaders had seen enough bouts of impoverishment and starvation that they agreed to a final cutback of the reservation. The land cession covered a very large area north and east of the Wind River. Altogether, the reservation was cut to about one-fourth its original size of 1868, thus accomplishing the goal of the first Wyoming territorial legislature. The transaction was supposed to include assistance for the two tribes including cattle and an irrigation system. The final 1904 deal, however, was not itself a land sale. Congress and the federal negotiators managed to ensure that the United States would be not the buyer but the broker, simply offering the land for sale to white settlers. Mondell promoted inflated estimates of what such sales would bring in. Those estimates went far toward assuring the tribal leaders that the revenue would provide what they needed in the way of livestock, schools, supportive payments, and a full-fledged irrigation system that could raise hay for cattle. Ultimately, however, the estimates were proved wrong. White settlers took up less than a quarter of the ceded lands—the best quarter. What was left remained unsold yet out of Shoshone and Arapaho control for about the next thirty-five years. The newcomer whites paid for the land they took up, but those limited proceeds couldn’t pay the real cost of the projected benefits for the reservation. In turn, those costs—particularly for the irrigation system—turned out to be, as usual for most irrigation projects in that era, woefully underestimated.58

The US government began work right away on the irrigation system for the lands remaining in the reservation but never completed it. That is true of every other irrigation system ever built by the US government for native people nationwide. Congress’s spending on reservation irrigation systems built under the Indian Service was dwarfed by what it spent on projects built on non-reservation lands by the new Reclamation agency launched in 1902. At Wind River, the expected cost of the entire irrigation system on the reservation system was eaten up by construction of just one major ditch, and that was all that revenue from the land cession sales could cover. Construction continued steadily, with water being brought to more and more acreage—twenty thousand acres by 1920. But after the first new ditch had been completed with cession sales money in 1907, irrigation became a new cost of farming. Native people on newly allotted “family farms” on the reservation found that they had to pay out cash just to try to make the land produce. The federal government charged water fees to cover construction, operation, and maintenance of the new irrigation system (the government refrained from charging interest on those costs). The new system meanwhile made some of the old hand-dug, free ditches inoperable. For people who had been told that they would get an irrigation system in return for ceding reservation lands, people who were just beginning to save seed and money for the next crop season and who had been pulled away from their fields to help build the new system, those terms were discouraging or impossible. Shoshone and Arapaho use of irrigated lands on the Wind River Reservation dropped steadily, while some white settlers took over allotments on the reservation by sale or lease and began to dominate the irrigation done with the new reservation system. The land base in use by native people, already drastically shrunk, became increasingly fragmented.59

The white settlers had a lot of frustrations driving them to help create that fragmentation. Lands held under allotment by Shoshone or Arapaho individuals were attractive for lease or purchase because they could be served by that slowly growing reservation irrigation system. The land that white settlers could buy on the ceded portion needed irrigation (though that was not much highlighted in the sales promotions), but a functioning irrigation system was even slower to arrive there.

Since 1898, Wyoming’s secretary of state and governor had been seeking cession of those lands with an eye to settlement. They and State Engineer Johnston had been fully aware of the need for irrigation to support any agriculture on the ceded lands. At the time Johnston opposed speculation in the Little Horse Creek case, he had thrown himself and his rhetorical flourishes into pushing for a huge irrigation project to cover over 330,000 acres on the ceded portion of the reservation. He described the project as one of several that would deliver Wyoming’s dream future, as he assured Wyoming readers. The projects, he promised, meant that “Wyoming is to witness a development along agricultural lines within the next few years which will place her among the first western states in the variety and volume of crop production.” Secretary of State Fenimore Chatterton, no rhetorical slouch himself, joined Johnston in pitching the glowing prospects for such a project and its future community of prosperous small farmers (presenting the usual overestimated profits and underestimated costs).60

Brandishing a State Engineer’s Office preliminary survey, Johnston and Chatterton managed to attract investors, a group led by a successful Chicago businessman who had grown up on a Nebraska farm and kept a hand in farm and irrigation ventures. Chatterton (while still in office) became the investor group’s lawyer, and in August 1906, Johnston issued to Chatterton, as the company’s lawyer, a very ambitious permit for use of Wind River water on the ceded portion of former reservation land.61

Johnston also undertook to vet and regulate the company’s construction work and its contracts with settlers, though the state had none of the official regulatory role it could have had under the Carey Act. The Interior Department, brokering the ceded lands, refused at the outset to make them a Carey Act project. Nonetheless, Johnston persisted in attempting to manage the development. To his great irritation, the Chicago businessman hired his own engineers to survey the lands and subsequently refused to build the big project, concluding that it would never be an economic success because of porous soils which would require expensive concrete lining on canals. As an experiment, the Chicagoan did build a small pilot canal system of about fifteen miles near the new town of Riverton that had sprung up in response to the prospect of land deals, irrigation on the ceded lands, and the glowing picture state officials had painted. The pilot ditches carried water, but the Chicago investor concluded that the settlers themselves were a key problem, because they “could not have made a success of any farming operations. Most of them were speculators who had come in when the reservation was first opened to settlers in the hope of some easy money. Real hard work in the fields was the last thing they were looking for.”62

The pilot system eventually watered only a little over ten thousand acres—about 3 percent of Johnston’s proposed grand total. The whole business was much in the press, with one newspaper accusing Johnston and the former secretary of state of betraying their trust as public officials by working with and for the Chicago investor group. They had aided a “colossal conspiracy” to create a monopoly on water rights via the grand 1906 permit, the paper charged. Johnston canceled the 1906 permit in 1910, then left the state in a huff. The next state engineer reinstated the permit with its valuable priority date intact and put it in trust in the hands of the state’s top officials in hopes of finding new investors.63

Finally, two groups of landowners organized on their own, one taking over the pilot ditch that had been completed, and the other getting Wyoming congressman Mondell’s help to take over and extend another ditch to water about twelve thousand acres. That ditch had been started by a Shoshone family on their land on the north side of the river before the 1904 land cession. State officials gave both groups portions of the big water permit from 1906, with arrangements for first dibs on water under its prized priority date. People who had waited ten years or more finally got water. Meanwhile, the rest of the big, grand project languished; it didn’t look profitable to any investor. The federal Reclamation office finally took it over in 1919. Wyoming congressman Mondell had meanwhile grown adept at tapping annual federal “Indian appropriations” bills for money to pay for irrigation infrastructure for white settlers on the ceded portion of the Wind River Reservation. Construction got underway with those funds. The project included, as had been originally envisioned, conversion of Bull Lake on the reservation into a reservoir feeding the Wind River for the settlers’ project. There was also a dam across the Wind River to raise water levels enough to divert it into a long canal running ten miles to reach project irrigated lands for settlers.64

All those ins and outs translated into mounting frustration for the new people who had come to the new town of Riverton following the government offer of land. Some, therefore, looked for places to make farms on lands in what remained of the reservation, where they could see the Indian irrigation system under construction. It was legal to lease or buy those reservation lands that had been parceled out as allotments, and so these newcomers did that.65

Individual native people accordingly came under pressure to lease or sell their allotments. And then the issue of water rights for those allotments became an issue that intensified the pressure to sell.

As the opening of the ceded lands to settlers was pending in 1905, the reservation superintendent had filed permit applications for state water rights for the lands on the reservation that were being allotted to individual members of the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes. The next year, the 1906 state water permit for the ambitious state-endorsed project on the Wind River began its long life. Under Wyoming water law, in order to keep their 1905 state priority rights alive ahead of that permit and its potentially massive water withdrawals, the native people had to meet permit deadlines to start using and keep using the water.

In Montana, much the same situation had developed. Native people on the Fort Belknap Reservation saw settlers up and down river starting to irrigate with state permits, before their own irrigation was fully underway. The federal agent in charge there, however, succeeded in getting a federal court to rule in 1905 that federal law ensured that the native people at Fort Belknap had the best water right on the river and could put that water to use at their own pace, independent of state law. In 1908 the US Supreme Court upheld the decision in the case, called Winters v. United States. The top court said that the tribe at Fort Belknap had rights to water, reserved to them with a priority dating from their treaty with the United States, for present and future needs, with no set amount or deadlines to be imposed by state law.66

As a historian of the Winters case has pointed out, the idea of such an “inchoate, unquantified, flexible reservation of water,” endorsed by the US Supreme Court, was attractive not just to native people but to some outside the reservation. Some white settlers in Montana welcomed the decision, believing it would attract federal investment for major water development in their area that would serve them as well as reservation lands. Certainly, the concept of an inchoate right, in these arid lands where projects could take a long time to reach full size, had been useful to Van Orsdel in supporting investment in Wiley’s Carey Act lands in Wyoming.67

Van Orsdel, remarkably, had a role in that Supreme Court ruling in the Winters case. In 1907, he was in Washington as an assistant attorney general and landed on the team arguing the case for Indian water rights in the Winters case before the US Supreme Court. As part of its decision upholding the Indians’ rights, the court agreed with an argument Van Orsdel made: that the United States could reserve land for its purposes, including Indian reservations, and water for that land would be reserved as well, independent of state water law. It is hard not to hear an echo of his argument a few years before in Wyoming, where he said state water law did not apply to land segregated and reserved by the federal government for a special purpose—in that case, irrigation under the federal Carey Act.68

Once the Winters decision was issued in 1908, the US Office of Indian Affairs and the US Department of Justice put it to work on the Wind River Indian Reservation. On a tributary of Owl Creek, near the northern border of the reservation, a Shoshone family named Duncan had previously been determined “competent” to take their own land, and so they had an allotment. In 1911 and 1912, the Wyoming water commissioner closed the Duncans’ headgates to ensure water would go down to whites who had been settled outside the reservation, near the mouth of the creek, since the 1880s. In response, the superintendent of the reservation told Washington that there needed to be a “test case” on reservation Indian water rights in the Wind River. To the “considerable annoyance” of the Wyoming water superintendent for the Wind and Big Horn basins, the US attorney filed a complaint in federal court in 1911 and again in 1912 against the water commissioner. The federal lawyer ultimately argued that based on the Winters case, Wind River Reservation lands and allotments on them, like the Duncans’ land, had water rights dating from the treaty of 1868—the best priority in the Wind River basin.69

The goal of federal officials on the reservation, following congressional policy, was, however, still to push native people on the Wind River Reservation onto small private farms. So in 1912, even as the case from Owl Creek got underway, the reservation superintendent and a special inspector from Washington met with both Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho members in council. The officials wanted tribal members to sell “extra,” unused allotted lands to white settlers. They said flatly that the state owned the water, and everyone had to follow state water law. The water right could be lost if the water was not used and the state permit deadlines, extended once, were now 1916. To get the water on the land by then, the people would need horses and plows—and, the officials said, they could raise the money for that by selling off land and reducing their family’s allotments to a workable forty acres. The reservation officials did not mention that at that moment government lawyers were challenging the power of state law over Wind River water for the reservation. They emphasized only state law deadlines.70

The meeting went on two days. Tribal members were skeptical that they would get much for their land and doubted they could move water onto remaining land in just four years. They noted that they had been pulled off their fields in just the past few years to build the new federal irrigation system to serve the allotted lands—including lands they were now urged to sell.71 The Arapaho wanted to go to Washington to confront the secretary of the interior about it, though others discouraged them.72 Big Plume, a member of the Arapaho council who had been on a delegation to Washington a few years earlier, had this to say (as translated by agency staff transcribing the meeting):

About eight years ago there was a government officer and he was setting just like you are now and he told us how we were to live. Two head men of the government here raised their hands to God saying they had done everything straight and that there would be no cheating of one another. That government man when we ceded that north portion of the reservation he told us himself that we should get one and a half million dollars for the other side or the ceded portion of the reservation. And we remember what he said about these ditches at that time. There was to be a certain amount of money set aside for these ditches and he told us you work on these yourselves and get the money back and nobody can say anything about these ditches, that is what he told us. These promises that were made to us were or have never been fulfilled as yet.73

Another tribal member commented:

And about these ditches, I cannot quite understand it, it goes hard on us all. This water I supposed was free to everybody because you all know that we could not live without water. These four years I cannot quite understand and it makes me feel bad to think that if we don’t get down to doing something this water will be taken away from us and our lands. When we ceded that other side we supposed we were going to get something out of it and why should they compel us to pay for these ditches. After they have taken the land away from us now they want to come and take our water away from us and after while we will have nothing left that we can call our own.74

The reservation officials responded that the secretary of the interior recommended that the native people sell more land simply because he was trying to do all he could to save their water in the face of state laws. “The water,” said the inspector from Washington, “appeared to be free as long as there was no demand for it. It is the demand by the white people who have made these laws that has brought these conditions about.”75

After this meeting, allotment sales were “successful,” the officials reported to Washington. Though they also told Washington that they were anxiously awaiting the result of the Owl Creek case, they appear never to have told tribal members about that until four years after that council meeting, when the federal court in Wyoming ruled on the case in June 1916. The ruling by Wyoming’s first federal judge, himself a former member of the state’s constitutional convention, upheld the Wind River Reservation’s 1868 treaty-based right to water based on the Winters case. A new superintendent immediately told agency staff to explain the decision to the Shoshone and Arapaho, to “assure them that their right to this water must not be interfered with” by state water officials. He told staff to watch state engineer staff to ensure that they followed the court order. By the mid-1920s, another case came before the next federal judge for Wyoming, Blake Kennedy (the longtime leader in the state Republican Party who drew a sharp picture of Carey in his memoirs). Kennedy too upheld 1868 treaty rights for the reservation, based on Winters. Citing Winters, Kennedy wrote, “The Government has reserved whatever rights may be necessary for the beneficial use of the Government in carrying out its previous treaty rights,” on the Wind River Reservation, and those necessarily included the rights to water for irrigation. These federal court decisions went unpublished, however, and can only be traced in government archives.76

Wyoming’s Congressman Mondell meanwhile railed against treaty-based rights for any tribe’s present and future needs. After the 1908 Winters decision, he described as “monstrous” the legal theory that he characterized as saying that in an arid country, there could be any power to “stay development until the crack of doom because there is somebody too indolent or too indifferent to develop.” And in all the decades to come, congressional action essentially echoed Mondell’s antipathy to treaty-based rights that could enable tribes to develop water over time. Congressional spending on reservation irrigation projects, which could have been a major aid in putting native water rights into use, steadily dwindled nationwide.77

At Wind River, the result was probably much as Mondell would have hoped. Over the next half-century, white settlers bought out forty-two thousand acres of land originally allotted to Shoshone or Arapaho people and leased thousands of acres more, all of which tended to be land reached by irrigation. The white settlers ended up dominating use of the new reservation irrigation system. Native people tended to dominate lands on private ditches on the reservation, however, because those ditches were built independent of the new irrigation system and were therefore not high cost. Shoshone and Arapaho people also had better access to grazing lands on the reservation kept for shared use (though managed by the federal government). Cattle herds supplied by the cession terms did well until a federal official supervising the reservation again forced communal herds into ownership by individuals, who sold them off.78

Haltingly, however, the idea Van Orsdel had formulated, of reserving water from the ordinary operation of state water law for certain places and people and their future development, continued to make its way forward. Even on the Wind River Indian Reservation, it eventually did so in the late twentieth century, based on the Winters case—to the chagrin of those who thought like Mondell.

Elsewhere in Wyoming, the US government, with a host of eager settlers behind it, soon pushed against the strictures of state water law that had been dear to Mead. In doing so, federal officials made full use of the views Van Orsdel had expressed.

Not on the Wind River but on the Shoshone River in the Big Horn basin, north of the Gray Bull, the new US Reclamation Service of 1902 decided to build one of its very first projects. To do so, the federal agency acquired an unused permit from 1899. The 1899 permit was part of a venture of Buffalo Bill Cody, who had made his career in the 1870s working as an army scout in Wyoming in summer and performing skits on the East Coast in winter about heroic army scouts. In the 1890s, Buffalo Bill, already famous for the world-traveling Wild West Show he would lead for decades, had a partner for development ventures: George Beck, who had a ranch near Sheridan and was the son of a US senator from Kentucky. Beck, a Democrat and perennial political hopeful for statewide office, had opposed the stockmen’s invasion of Johnson County, in 1892, and warned fellow cattlemen not to join it. A couple of years later, he saw the Big Horn basin from atop the Big Horn Mountains, imagined it as akin to the Promised Land, and talked Buffalo Bill into joining him in irrigation ventures there.79

It was Beck and Buffalo Bill who hired Van Orsdel as lawyer and Mead as engineer to work for them as a team, several times in the 1890s, to lay out irrigation plans. Mead was not immune to the intoxication of potential development. In some ways, he was the biggest dreamer of all. Contrary to the grim realism of his description of the entire Big Horn basin for Wyoming readers in 1898, in 1896 he had written a flowery piece for a national irrigation booster magazine on behalf of Buffalo Bill’s first canal project on the Shoshone River:

Ever since the advent of the first emigrant this tract of land has been a source of longing to the homeseeker. As the possibilities of this region became better understood its attractions have increased until it has become generally known and regarded as the most extensive and desirable body of irrigable land in the state.80

Unfortunately, Mead was no better than any contemporary at foreseeing the obstacles to irrigation projects. For even the relatively modest first project that Buffalo Bill proposed for the hopeful “homeseekers” in his namesake town of “Cody,” Mead’s survey and projections for Shoshone canal projects proved woefully inadequate.81

Buffalo Bill also had a second, more ambitious plan: diverting part of the big Shoshone River to irrigate bench land above it. Despite their combined Kentucky charm and Wild West Show star power, Beck and Buffalo Bill never could pull funding together for that one. They did, though, secure a state water permit for it, signed by Mead in 1899.82

Though Buffalo Bill and Beck didn’t build their dream project, its 1899 permit was tantalizing. Perhaps water for that imagined project could take priority over water for the various irrigators who had moved onto the Shoshone River, with smaller-scale efforts, soon after 1899. Under the Reclamation Act, the federal government had to have state water permits for its irrigation projects. The new federal Reclamation Service acquired Buffalo Bill’s 1899 permit as a cornerstone for the service’s own grand ideas for the Shoshone. It also applied for and got additional permits from the Wyoming State Engineer’s Office for water storage and other aspects of the project federal engineers were designing, which was even more ambitious than Beck and Buffalo Bill had dared propose.83