11

Fraud!

Parry stared as if Bragg had taken leave of his senses.

‘Good Lord, Bragg,’ he questioned, ‘what on earth are you talking about? A matter for the police?’

Bragg was in no humour for answering questions. ‘Look here, Parry,’ he said, ‘you keep your mouth shut about this. See? Now, we’ve got to report to Marlowe. You go and catch him in case he should go out. I’ll follow when I get one or two of the tracings. Here, take your book of sections.’

When Bragg was in this state of mind Parry knew that it was best to do what he wanted without comment. He rolled up his book, went down the passage, and after tapping at another door, opened it and passed through.

It led into a small room furnished in a rather better style than the drawing-offices. At a typewriting desk sat a good looking young woman with a pearl necklace and gold bangles.

‘Hullo, Miss Amberley! Chief in?’ Parry grinned at her.

‘I’ll find out.’

She disappeared through a door in the side wall, leaving Parry standing before her desk. He was keenly interested in this cross section affair and glad that Bragg had not taken it entirely out of his hands. It would have been rather like Bragg to do so. He was inclined to get particulars about things from others and then shove them in to Marlowe himself. Not unfairly exactly: he gave credit where it was due. All the same—

‘Mr Marlowe can see you now.’

The girl held the door open and Parry passed through. The chief was writing at his desk. He looked up. ‘Well, Parry, how’s the Widening?’

Marlowe was generally reputed to be somewhat unapproachable, but Parry had always found him easy enough to get on with. He had been particularly friendly when appointing Parry to his present job. Since then Parry had been with him on different occasions in connection with the work, always leaving with the same pleasant recollections of the interview.

‘All right, sir,’ Parry answered; ‘everything’s going on as usual. Bragg sent me in to see you about a rather curious thing that’s happened. He’s following when he gets a tracing.’

Marlowe sat back in his chair. ‘Well,’ he said, ‘that’s not a bad beginning for a story. What’s the epoch making event?’

‘We’ve found, sir, that a lot of our cross sections are wrong.’

‘Oh?’ Marlowe’s manner at once grew sharp. ‘What do you mean?’

Parry explained in detail. Marlowe nodded, but made no comment. ‘We’ll wait for Bragg,’ he said.

At that moment Bragg entered.

‘Bring over chairs, you two,’ Marlowe went on. ‘Now, Bragg, what’s all this about?’

They settled themselves round the table desk, the cross sections upon which the inquisition was to be held lying between them.

‘Parry has explained what we’ve discovered?’ Bragg asked.

Marlowe nodded.

‘Then I’ll tell you, sir, what occurred to me when I was thinking over the thing last night. So that you’ll understand, I shall have to remind you of just what I knew when I went home. Firstly, we had found that there was a sheet in Parry’s book of cross sections which differed from the linen originals by just one figure in each of two sections. Secondly, that part of a torn sheet of the same sections had been found which was identical with the original, and therefore, of course, different from Parry’s. Thirdly, that exactly similar pencil notes written by both Ackerley and myself, appeared on each of the sheets. I was aware also, of course, that so far as was officially known, no mistake had been made in getting out these sections and no revised linen originals had been traced. Further, I was perfectly sure in my own mind that I had not written the note about the piping of the field drain twice.’

Marlowe nodded again. He was listening with close attention.

‘It was obvious, therefore,’ went on Bragg, ‘that someone had secretly copied this sheet, and I asked myself why had this been done? At first sight I supposed that one of the boys had made a mistake in his levels and hadn’t wished to give himself away. But as I thought over the thing further, this seemed to grow less and less likely. If any of the boys in the office had done so, he would have destroyed the original linen tracing and replaced it with his own new one. Do you agree with me so far, sir?’

‘Yes, I think so,’ Marlowe answered. ‘And there is surely another consideration which points the same way. None of the boys would have made a new tracing. He would simply have rubbed out the incorrect portions he wouldn’t have done even this off his own bat. He would have spoken to you, said he had made a mistake, and consulted with you as to the easiest way of dealing with it.’

‘I quite agree,’ said Bragg. ‘I thought of those points, too. I may say also that when I examined that one original tracing yesterday in response to Parry’s request, I saw no discoloration at the figure. If the figures had been altered there would have been discoloration. I’ve brought in one or two of the tracings and you can see for yourself that they’ve not been altered.’

‘Quite,’ Marlow returned.

‘I thought over all these points,’ Bragg repeated, ‘and the more I did so, the more they seemed to involve a very serious conclusion; so serious that for a long time I hesitated to accept it.’

‘I don’t follow that,’ Marlowe interrupted.

Bragg moved uneasily. ‘Well, it seemed to me to follow that this new sheet was made by someone outside the office.’

‘Oh.’ For some moments Marlowe sat whistling absently beneath his breath. ‘’Pon my soul, Bragg, it looks like it. Very nasty that. Well?’

‘I went over the premises again and again, but I just felt more strongly forced to this conclusion. So I accepted it provisionally, and I asked myself the question, Who outside the office could have done it?’

Bragg paused in his turn. Marlowe seemed a good deal upset, while Parry found himself filled with excitement.

‘I hate to go on,’ Bragg said at last, ‘but you must see for yourself that only one answer was possible. If none of our men made this alteration, it must have been done by the contractors. Very unwillingly I asked myself why.’

‘Ah,’ repeated Marlowe, ‘why? Were you able to answer that question?’

‘Not at first. For a long time I puzzled over it. Then I began to consider the precise change which had been made, and suddenly I saw its significance.’

Marlowe made a gesture of impatience. ‘I’m hanged, Bragg, if I can see it even now. Go ahead and explain.’

Bragg took a sheet of paper from his pocket and laid it on the desk.

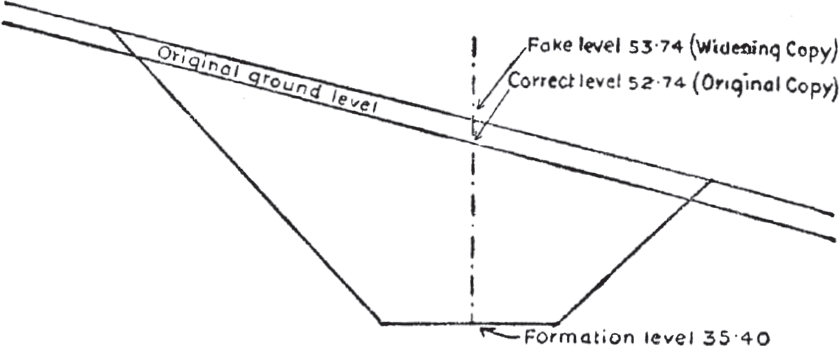

‘This sketch of section 48, showing both original and faked levels on one sheet, will I think, clear it up. Just see the result of the alteration. The level of the bottom of the cutting is shown the same on both copies as 35.40. But on the Widening copy the original ground level is shown one foot higher than the office copy. Now, sir, I think we may take the office copy as correct and the Widening one as a fake. The result of the fake will, therefore, be that the cutting is shown one foot deeper than it really is, 18 feet instead of 17 feet.’

‘And you take your quantities for the certificate off these sections?’

Bragg nodded. ‘That’s it, sir.’

Marlowe was frowning angrily. ‘Then these infernal scoundrels are being paid for doing more excavating than they really have done? Is that what you mean?’

‘That’s the only conclusion I could come to,’ Bragg answered. For a moment there was silence, then Bragg continued. ‘There are two more things to consider. First, as of course you know, that foot involves a good deal more than appears at first sight. Owing to the flat slope of the sides the cut at the top is very wide, and that last foot, therefore, means a quite disproportionate increase of cutting. I have worked it out for this section. The depth is altered from 17 feet to 18, that is an increase of 6 per cent, but the area is increased by over 100 square feet, or over 9 per cent. It means that for the hundred feet of length ruled by that section, the fake shows an increase of nearly 400 cubic yards, and at the scheduled rate of 2/6 that’s close on £50. And this is one of the smallest cross sections altered.’

‘What would it amount to altogether?’

‘I don’t know, sir; I’ve not had time to work it out. But I should say off-hand that the total would be at least three hundred times as great. That would be £15,000. Say from £12,000 to £18,000. That’s as much as they would dare exceed the earthwork estimate, or more, without having the whole thing gone into from A to Z.’

Marlowe thought for some moments.

‘Are the faked sections altered; I mean the drawings? Are they shown deeper than the originals?’

‘Oh, yes, it’s not confined to the reduced levels. The actual drawings are altered to suit.’

‘Then there should be no difficulty in proving the drawings wrong?’

‘Oh, none. It only means relevelling the ground at the top of the cuttings.’

‘Very well; let’s have the things checked. We must be absolutely sure of our ground before we raise any question.’

Once again silence descended on the little group, broken again by Marlowe.

‘I’ll tell you another thing; we’ll have to check the other plans as well. For example, what about the concrete cube in the bridges? A very small alteration in overall dimensions would make a hell of a lot of difference in the money.’

‘I don’t think, sir,’ said Parry speaking for the first time, ‘that there could be much error in the bridges. All the concrete work has been checked again and again.’

‘I know,’ Marlowe said impatiently, ‘but was it checked off correct plans?’

To this Parry could make no reply. He shook his head in silence. Marlowe turned to Bragg.

‘Tell me, Bragg, who is responsible for all this? Who actually carried it out?’

It was now Bragg’s turn to shake his head. That was what he had himself been wondering. He had considered everyone whom he had thought possible, and had dismissed each from his mind. Marlowe looked at him keenly.

‘You naturally don’t like to put it into words,’ he said, ‘but the idea must have occurred to you. Is there,’ he dropped his voice instinctively, ‘is there any connection between this affair and the recent tragedy?’

Parry felt his heart beat faster. This suggestion surely offered a solution of the whole terrible affair? If Carey had done this thing and in some way learnt that discovery was imminent …

‘That idea, of course, occurred to me,’ Bragg said slowly, ‘but I didn’t see that there could be anything in it. Any money the scheme would bring in would go to the contractors; I mean to the firm. Carey wouldn’t have got any of it.’

‘Unless they were paying him to do this.’

Bragg shrugged. ‘They’re a reputable firm. I can scarcely see them committing a criminal fraud.’

‘So I should have said,’ Marlowe answered, ‘but we must remember that times are pretty tight at present. A few thousand might even stave off a bankruptcy. Another point, Bragg. Have you considered how these faked prints could have been produced?’

‘Only, so far as I can see, by making a new set of tracings from the book we sent down. The sections and levels would be altered as the tracing was done, then two new sets of prints would be got. Any existing notes would be copied on to the new prints and these would be put into our covers.’

‘Yes, I dare say you’re right. But—’

Marlowe’s desk telephone rang stridently.

‘Marlowe speaking,’ he answered. ‘Oh, very well, Miss Hunt. Any time he comes down.’ He replaced the receiver. ‘That’s the chairman. “He’s down here today and wants to be taken round the yard. You two’ll have to clear out. Now remember, both of you, not a word of all this to anyone. You come in and see me again, Bragg, say about four. Graham’s not here today, is he?”

‘No, sir. He’s gone to meet the Ministry of Transport Inspector about that Lydminster derailment.’

‘Of course. Parry, you’d better get back to Whitness. There’s no need to have everyone wondering what’s up. That’ll do.’

‘If you scoot, you’ll catch the 12.55,’ said Bragg as they reached the passage. ‘Better leave your book with me.’

Parry nodded. He had three minutes and he had to run. He stepped into the train as the guard waved his flag.

Parry sat motionless in his corner seat, his mind full of this strange affair which had just come to light, an affair, as far as he knew, without parallel in the annals of railway contracting. Would it, he wondered, really come to a police prosecution? If so, against whom would the prosecution be brought? He tried to look at it from a detached point of view, to estimate how Bragg’s theory would appeal to outsiders such as the jury in a court of law.

Contractors, he reflected—it was the professional outlook—were often very tricky people, given to sailing close to the wind and not always above a lapse into actual sharp practice. But they were not swindlers or forgers. It was one thing to put a strained interpretation on a specification clause, but quite another to falsify figures. Parry agreed with Bragg; unless in the face of overwhelming evidence no jury would hold that the firm, as a firm, had stood for the fraud. All the same he could imagine the Railway Company proceeding against the firm to recover their loss, on the ground that though the principals might not have been involved, their agents were. Whether, however, this position could be maintained, he did not know.

The next two days he and Bragg spent in comparing the Widening office prints with the originals from headquarters. It was a tedious job, for beside the viaduct there were several smaller bridges, not to speak of culverts and other less important works. But nowhere could they find any other discrepancies. The fraud seemed to be limited to the excavation.

The checking of the cross sections on the ground was simultaneously done by Ashe and a couple of other juniors. They found, as was expected, that the head office copy was correct and the Widening copies wrong.

Parry naturally badgered Bragg to know what was going to be done. Nothing, Bragg told him, not till all the facts were known. He had made an estimate of the amount the scheme would have netted for the contractors, and it amounted to £16,750. Marlowe, however, was going to make no move till all possible investigations had been made. Then he proposed to get the contractor partners down, put the facts before them, and ask them what about it?

Five days later this meeting was held, very secretly. Parry indeed did not hear of it till it was over. Marlowe, Graham and Bragg were present on the Company’s side, while the contractors were represented by the partners, the Mr Spence who had been present at the inquest and his cousin, Mr Elmer Spence, together with their accountant, a man named Portman.

It was from Bragg that Parry heard what had taken place. Marlowe had opened the proceedings by apologising for calling such busy men down to Lydmouth in so urgent a manner, and by expressing his regret at the unpleasant nature of the communication he had to make. Then he said he proposed to put the whole of his cards on the table, and he called on Bragg to explain what had taken place.

Bragg told the whole story, beginning with Lowell’s discovery of the torn print and giving details of the inquiries this had given rise to, right down to his estimate that, had the affair not been discovered, the contractors would have received between £16,000 and £17,000 to which they were not entitled.

Marlowe then took up the tale again. He said his visitors were not to misunderstand his attitude: he was very far indeed from suggesting any fraudulent intention on the part of the firm. All the same, as they would see for themselves, the facts required explanation. He was sure the partners would be even more ready to give this to him, than he was to ask for it.

Mr Elmer Spence, the senior partner, who showed signs of emotion, then got up and said that, speaking for himself, he felt appalled and overwhelmed by what he had just heard. He need scarcely assure Mr Marlowe that the facts had come to him as a complete surprise and a devastating blow, and he could not at such short notice make any kind of detailed reply. For the present he must, therefore, content himself with a couple of remarks. First, he wished to express his heartfelt regret that anything had happened which called in question the honour of his firm. Next, he would like to say how much he appreciated the direct and considerate way in which Mr Marlowe had acted, in calling himself and his partner there and telling them privately exactly what appeared to be wrong. He could assure Mr Marlowe that he would be equally straight with him. He would hold an immediate and searching investigation into the affair. If anyone were found to be guilty he would be prosecuted without respect to his position or influence, and finally, if it were found that his firm had received any monies to which they were not strictly entitled, every penny would be at once refunded.

To this Marlowe replied that he thanked Mr Spence for taking up the attitude he had, which was just the attitude which he, Marlowe, had believed the head of a firm with so high a reputation would take up. They on the Company’s side would await with interest the result of Mr Spence’s inquiry. In the meantime, before parting, could they not settle the date of their next meeting, at which they would hear this report? After discussion a further meeting was arranged for that week, and the protagonists parted on outwardly amicable terms.

Mr Spence was as good as his word. The very next day a searching inquiry into the whole affair was begun in the contractors’ office at Whitness. Parry and Bragg were politely asked to give evidence, but were not invited to remain when their respective hearings were over. Every endeavour was made to keep the details secret, and while the staff knew that a big row was on, no one who was not actually concerned had any idea of what it was all about.

Before the end of the week Messrs Spence sent Marlowe a confidential report of their findings. They began by saying that they had made a formal investigation into the matters brought to their notice by the Company and that the weight of evidence—of which a précis was given in appendix A—had led them to the following general conclusions:

- That the affair did in point of fact constitute a deliberate fraud, perpetrated with the object of obtaining money upon false pretences from the Railway Company.

- That the directors and officials of Messrs John Spence & Co. were, as a whole, entirely innocent of participation in the fraud, and were indeed quite ignorant of its existence until receiving the Railway Company’s communication thereon.

- That the fraud owed its inception to, and was carried out by, their late chief resident engineer, Mr Michael John Carey.

- That no other person in the employment of the firm, or connected with it in any way, was party to, or was aware of, the fraud.

The report then went on to say that the partners, though personally not in any way to blame for the affair, had unhesitatingly decided to make themselves responsible for their late engineer’s actions, and were prepared to refund whatever sum the Company had lost as a result thereof. They, therefore, proposed the setting up of a small joint committee to go still further into the matter and ascertain the amount of this sum.

‘I say, Bragg,’ Parry observed when Bragg showed him the document, ‘all that’s rather a triumph for you. If you hadn’t stayed awake at night thinking about it, the Company would have lost their sixteen thousand.’

‘As far as a triumph for me is concerned,’ Bragg returned, ‘you have as much to say to it as I. I may tell you that Marlowe is pleased with you about it.’

Parry grinned crookedly. ‘I did nothing,’ he said, ‘but if Marlowe thinks I did, for goodness’ sake don’t disabuse his mind.’

Presently Parry asked a question. ‘There’s one thing I don’t understand, and that is how Carey could have got the cash. D’you remember, you said yourself that one of the reasons he could scarcely have been guilty was that the cash would go to the firm and not to him?’

‘Ah,’ said Bragg, ‘we had a job to find that out. But Marlowe handled them well and they had to tell. They were giving Carey a huge commission on both extras and excess profits. No less than twenty per cent net. He would have made about three thousand out of the fraud, and I should be inclined to bet the whole three that no question about the savings would have been asked.’

‘Still,’ Parry persisted, ‘I don’t quite understand how it was done.’

‘Well, it’s simple enough. Each certificate showed so many yards excavated at so much per yard, totalling such a sum. Suppose it showed 8000 yards at half a crown. That would mean that the contractors were due £1000, and £1000 they were paid. Now, suppose their excavation costs for the period came to, say, £600: that was £400 profit on 8000 yards. But the normal profit they had reckoned on for those 8000 yards was, say, £200. Carey had, therefore, made an excess profit of £200, and of this they paid him twenty per cent, or £40. Follow it now?’

‘Yes, I see that,’ said Parry; ‘jolly cute.’ He paused in thought, then went on slowly: ‘But surely, Bragg, when these enormous profits began to come in, the Spences must have known there was something wrong. They must have known they couldn’t have been earned.’

Bragg shrugged. ‘You may hold what opinion you like about that,’ he answered. ‘Marlowe put it to them in the neatest possible way. Naturally they weren’t admitting anything. They said the profits, even with the fraud, were not by any means abnormal, and that they put them down, partly to Carey’s organising ability, and partly to the use of those new Benbolt shovels with the direct delivery on to the conveyors. Of course, there was nothing to be said to that.’

‘No,’ Parry admitted, ‘but it’s damned fishy all the same.’

Some days later Parry found himself nominated with Bragg and Mayers, of the clerical staff of the office, to represent the Company on the small committee which was to ascertain the amount of the contractors’ refund. In the end the sum was unanimously fixed at £11,465.

It was about this time that a faint rumour began first to be whispered. In the extraordinary way that rumours have of coming into being without ascertainable cause or source, this rumour was born, took on shape and grew to maturity.

Immediately that news of the fraud had leaked out it had become connected in the public mind with the suicide of Carey, it being believed that in some way that unhappy man had seen that discovery was inevitable, and being unable to face the consequences, he had taken the easiest way out. But this new rumour went farther.

It began with the suggestion that a fraud of the magnitude of that which had just occurred, could not possibly have been carried out by one man. It was argued that a confederate on the Company’s side would have been absolutely essential. From this it required but a slight effort of the imagination to suggest that Ackerley had been the confederate in question. Finally it was hinted that not only was Ackerley’s death suicide, due to the fear that the affair was coming out, but that the railway officers knew this to be the case.

Parry’s furious denunciations, when at last these suggestions were put to him, did little to discount them. It was immediately remembered that not only had Parry been a special friend of Ackerley’s, but that he was intimate with, if not actually in love with Ackerley’s sister. His view, it was assumed, would be biased.

When matters were in this stage substance was given to the rumour by an altogether unexpected development. Mayers, the clerical member of the staff who had sat on the small committee with Bragg and Parry, came forward with an unpleasantly suggestive story.

It appeared that some three or four days before his death, Ackerley had paid a visit to the Lydmouth office on business connected with the Widening. When there he saw Mayers. They were speaking of costs and quantities when Ackerley accidentally disclosed the fact that he was worried about the excavation. The question had arisen out of a discussion with one of the gangers as to the amount of clay held by a small ballast wagon, he and the ganger differing on the point. For his own information he had made a test. From the ballasting returns he had taken out the number of wagon loads carried from a certain cutting. The cube removed from this place was known from the cross sections, and from these two figures he was able to calculate the average wagon load. This came out higher than either Ackerley or the ganger had estimated. Ackerley had followed up the matter by selecting a dozen loaded wagons at random, and sending them into Redchurch to be run over the wagon weigh-bridge. To his surprise he found that the ganger’s lower figure was right after all.

The calculated and actual weights were therefore different. Ackerley evidently had not considered the matter serious, but he had said he was going to make some further experiments. He had never had an opportunity to do so. Mayers had also considered the matter unimportant and had said nothing about it. But it was now seen that had Ackerley pursued his inquiries, he must have come on the fraud.

Parry was able to remind Mayers that part of his recollection was inaccurate, for on that very day Mayers had repeated the story to him. Apparently, however, neither Parry nor Mayers had told it to anyone else.

Now, however, when the matter was made public, Parry hotly argued that the story was in itself a proof of Ackerley’s innocence. Had he been involved, Parry pointed out, he would never have carried out those tests nor spoken of them to Mayers. But against this it was argued that even at this time Ackerley saw that the fraud was about to come out, and that he was preparing the way for a ‘discovery’ by himself. It was further suggested that he had seen the same danger as Carey, but that Carey had been able at that time to divert suspicion, though later this had passed beyond his power also.

When, as eventually happened, the rumour reached Mr Ackerley’s ears, the old man’s distress was pitiable. Parry’s repeated assurances that no one in authority believed the story did little to comfort him. A slur had been cast on his son’s name, and he could not and would not rest till it was removed. But in the end he saw that he could do nothing. The suggestion was not printed in any paper nor had anyone made any direct statement about it before witnesses. No action at law was possible. Even, however, had it been, Mr Ackerley recognised that no such action would clear away the stain. At most it would show that Ronnie’s guilt could not be proved; under no circumstances could it establish his innocence.

And then, as the days began to pass on, the police suddenly took drastic and unexpected action, causing a fresh shock to the workers on the Widening and extending public interest in the affair from a local to a national basis.