The Coming of the Waste Land

It’s controversial enough in scholarly circles today to suggest that the Knights Templar may have been something other than a body of ordinarily devout Catholic warrior-monks. It’s even more controversial to suggest that the Templars may have possessed a body of secret knowledge that was passed down to successors after the destruction of the Order. The consensus view among historians of the Middle Ages holds that the odd reputation of the Templars was purely a product of slanders against them that were concocted by the French monarchy, and that there’s no evidence that any fragment of Templar tradition survived in any form.192

Standing apart from that consensus is a minority of researchers who argue that some elements of the Templar tradition can be shown to have survived after 1311. While this view is unpopular in scholarly circles these days, there is much to recommend it. As already noted, most of the Templars survived the end of their order and were permitted to join other knightly or monastic orders, and presumably took with them whatever teachings they had learned from the defunct Templar order. This might explain some of the evidence for the temple tradition at Glastonbury, among other things, and this suggests that it would be worth studying monastic culture, agriculture, and architecture across Europe after the downfall of the Templars, to see if more traces of the survival of the temple tradition might be found there.

Whatever did or did not find its way into monastic communities by this means, there is another route by which Templar teachings seem to have survived the order, and this involves the long-rumored Templar foothold in Scotland. It has been pointed out that during the years of the Order’s dismemberment, from 1307 to 1314, the kingdom of Scotland was subject to a papal interdict. While an interdict was in force, no Christian sacraments could be administered and the Church suspended all its activities. In a strict sense, the dissolution of the Order of the Temple at the Council of Vienne in 1311 thus had no legal effect in Scotland.

There are a great many tombstones in Scotland with Templar symbols on them, some dating from well after the Order’s dissolution, and Templar symbols abound in certain important works of Scottish medieval architecture, including Rosslyn Chapel, which will be discussed later in this chapter. It has therefore been suggested that the Templars who were in Scotland in 1307, along with some who fled there from elsewhere, continued to function as an organization for some time after 1311, and preserved many of the traditions of their Order; that some of these surviving Templars, given the Order’s known expertise in building castles and churches, would have found ready employment in the construction trades; that they passed on Templar teachings to Scottish stonemasons’ guilds; and that these teachings, in jumbled, fragmentary, and incoherent forms, can now be found among the symbols and practices of Freemasonry.

It’s by no means an impossible suggestion. Stranger things have happened often enough in history, and serious historians such as John Robinson have lent their considerable support to the claim.193 What renders the theory all the more intriguing is that some such connection is required to account for one of the most important themes of the higher degrees of Freemasonry—the tradition, discussed in Chapter One, that a secret chamber lies directly beneath the Holy of Holies of the Temple of Solomon and can be reached by a hidden tunnel.

What makes this tradition of critical importance is that the tunnel actually exists.194 It was discovered in 1968 by a team of archeologists headed by Meir Ben-Dov; it starts at an undisclosed location outside the Temple Mount, passes under the Triple Gate and Stables of Solomon, and proceeds directly beneath the Dome of the Rock on the site of the Temple. Ben-Dov’s team identified it as dating from the time of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. The explosive religious politics surrounding the Temple Mount in1968, one year after the Israeli conquest of east Jerusalem, forced Ben-Dov to dig only as far as the Muslim authorities permitted, and the latter were adamant in refusing to allow any excavation beneath the Temple Mount itself. To this day, what might be at the far end of the tunnel remains unknown.

From 1118 until the Crusaders lost Jerusalem in 1187, most of the Temple Mount, and in particular the Stables of Solomon, were in the hands of the Knights Templar. A tunnel excavated by Crusaders in that place was almost certainly the work of the Templars and would certainly have been known to them even if it had been dug by other Crusaders before the Templars took over the Temple Mount. A great deal of speculation has fastened on that fact and spun various narratives about what the Templars may or may not have dug up. It’s less often noticed that the existence of the tunnel provides remarkably strong evidence for a direct lineal connection between the Knights Templar and modern Freemasonry.

Until the archeologists uncovered the tunnel in 1968, to be precise, there was no way that anyone could have known that it existed unless that information had descended to them from the original excavators of the tunnel. Nor could they have known by any other means that the tunnel ran from underneath a royal palace—the palace of the Kings of Jerusalem was on the southern end of the Temple Mount, directly over the Triple Gate and the Stables of Solomon—more or less horizontally toward the location of the Holy of Holies of Solomon’s Temple.

The Masonic degree of Perfect Elu, which describes the horizontal tunnel in detail, can be found in manuscripts dating from no later than 1771 195—that is, nearly two centuries before the 1968 excavations, and also well before earlier archeological digs in 1867 and 1911, which found some evidence of tunnels and chambers under the Temple Mount.196 The relevant question here is as simple as it is challenging: how did Freemasons in the eighteenth century know about the existence, location, and direction of a tunnel that was not discovered for more than two centuries, unless they inherited that knowledge from the people who dug the tunnel in the first place?

The vertical descent of the workmen to the secret vault, the legendary incident at the heart of the Royal Arch degree, also makes considerable sense in the light of the Temple Mount’s archeological realities. The very few archeological surveys that have been done of the Mount itself show, as already noted, that the entire hill is riddled with abandoned tunnels, cisterns, storerooms and drains. Workmen clearing away rubble on the Temple Mount, whether their labors took place in the time of Zerubbabel or of Hugh de Payens, would very likely have encountered the sort of opening in the ground described in the Royal Arch degree. Whether that opening gave indirect access to a secret vault under the Holy of Holies is another question, one that will probably never be settled until and unless archeologists are permitted to excavate the Temple Mount—but the possibility can’t be dismissed out of hand.

What the Templars found in their excavations beneath the Temple Mount, if they found anything at all, remains a mystery, and it’s impossible to say for certain whether that mystery has anything at all to do with the temple tradition that has been explored in this book. The relevance of the tunnel to the theme of this book is simply the evidence it offers that at least some elements of Templar knowledge must have been passed on to operative masons’ guilds in Scotland after the abolition of the Templar order in 1311, and therefore fragments of the same knowledge may have reached the speculative Masonic lodges that emerged out of the operative guilds some four hundred years later.

The exact process by which that knowledge made its way from the Templars to the Freemasons has not yet been traced, and may never be known. One important piece of the puzzle, though, may be found in an enigmatic building in Scotland, the famous Rosslyn Chapel.

The Rosslyn Secret

The Collegiate Chapel of St. Matthew, to give this remarkable structure its proper name, stands on the hill above Roslin Glen, eight and a half miles from Edinburgh—close enough to attract a steady stream of day-trip buses and private cars in tourist season. Rosslyn Chapel is among the most beautiful surviving works of medieval Scottish architecture, but that fact accounts for only a modest fraction of the visitors. The rest are there because of the legend that has come to surround the chapel—a legend that touches on most of the themes discussed in this book and focuses with particular force on the Knights Templar, the origins of Freemasonry, and the rumored secret that connects them.

Rosslyn Chapel was a creation of the fifteenth century and thus falls precisely into the gap separating the last known Templars from the first known Freemasons. The span of years during which it was built, curiously enough, also frames the period in which Fütrer and Malory revived the legends of the Holy Grail. Its cornerstone was laid on St. Matthew’s day, September 21, 1446, and it was finished in 1486. It was originally built by William Sinclair, Earl of Caithness, as a place of worship for his family close to their home at Roslin Castle—this was a common custom of the medieval aristocracy, in Scotland as elsewhere.

Even in its present, half-ruined state, the chapel is a masterpiece of late Gothic design, and it also shows most of the telltale marks of the temple tradition discussed in part two. Readers of this book will already know, for example, that it stands atop a hill, is built of strongly paramagnetic stone, and has an axis running due east and west, aligned precisely on the rising sun at the spring and autumn equinox. In point of fact, all the elements of the temple technology that were able to survive the ravages of time and the violence of the Reformation are present and accounted for in Rosslyn Chapel.

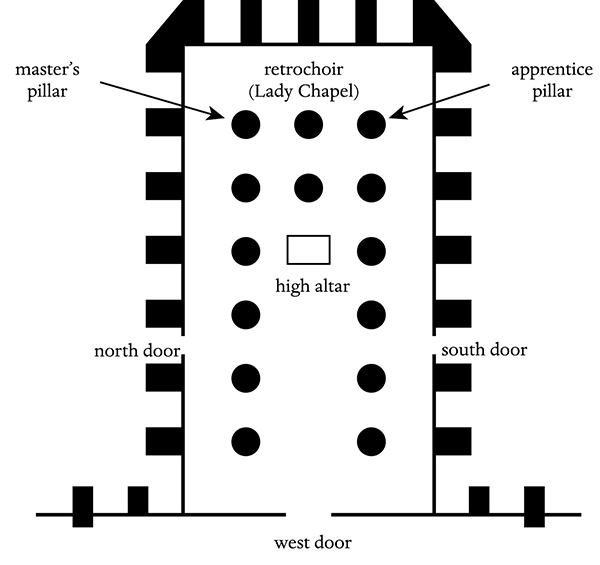

Various researchers on Rosslyn Chapel have claimed that the structure is modeled on the Temple of Solomon.197 A more precise description is that it borrows certain design elements of the Temple of Solomon and combines them with those of Gothic church architecture. For example, the usual orientation of Christian churches, with the altar in the east, has been modified to make room for a representation of the temple’s design, with the doors in the east: the Lady Chapel in the retrochoir beyond the high altar stands in for the porch of the Temple of Solomon, with the famous Apprentice Pillar and Master’s Pillar filling in for the great pillars Jachin and Boaz, respectively. On the other hand, many other aspects of the design of Solomon’s Temple have no equivalent in Rosslyn Chapel; to note the obvious example, there is no Holy of Holies, just a standard high altar in the middle of the eastern half of the building.

rosslyn chapel

As in most medieval churches and chapels, there is also a crypt—that is, an underground space used for burials and certain other traditional purposes. Rosslyn’s crypt is east of the main structure and can be reached by a stair on the south side of the Lady Chapel. This is closed off to the general public, and what exactly might be found there by careful excavation is an interesting question. Many Rosslyn Chapel researchers have argued, for various reasons, that there may be an additional crypt concealed somewhere near the chapel, perhaps reached via a sealed door in the known crypt, perhaps not.198 For reasons we’ll be discussing shortly, this hypothesis seems worth following up; it would be especially interesting to see, if any secret crypt is discovered, whether it has anything in common with the secret vaults that play so important a role in the rituals of the higher degrees of Freemasonry.

Other references to higher Masonic degrees are certainly present at Rosslyn. The only line of text anywhere in Rosslyn Chapel, for example, is found on an architrave in the Lady Chapel. It reads Forte est vinum, fortior est rex, fortiores sunt mulieres, super omnia vincit veritas—“wine is strong, the king is stronger, women are stronger still, but truth overcomes all things.”199 From most perspectives, this is an odd thing to read in a medieval chapel, not least as the only inscription in the structure. Seen in the proper context, though, it’s extraordinarily revealing.

These words are part of a story found in the apocryphal book of Esdras and also the writings of the Hebrew historian Josephus. It is by saying these words, according to the story, that the Jewish prince Zerubbabel wins a competition at the court of the King of Persia and, as a reward for his wisdom, receives the king’s permission to complete the rebuilding of the Second Temple. That same story plays a central role in the rituals of some of the oldest high degrees in Masonry—the three Knight Mason degrees and their equivalents in other Masonic rites, as described in Chapter One of this book.

Most versions of the degree, including that preserved by the Knight Masons, quote the words carved into the stones of Rosslyn Chapel. It’s remarkable, to use no stronger word, to find this connection to Masonic rituals about the rebuilding of the Temple of Solomon in a structure that may, in some sense, have been intended as a reconstruction of that temple. It is even possible—though much more research would be needed to settle the question one way or another—that in the Knight Mason and kindred degrees, today’s Freemasons still have a version of rituals that were once secretly performed at or near Rosslyn Chapel.

It’s also possible, if this is the case, that the old and otherwise puzzling tradition of referring to higher Masonic degrees as “Scottish,” whether or not they have any obvious collection to Scotland, may ultimately derive from that connection. If a ritual originally practiced among stonemasons at Rosslyn Chapel ended up in the hands of speculative Masons in England, “Scots Master” would be a reasonable name for it.

The case for a Templar link to Rosslyn Chapel need not rely on anything so indirect as Freemasonry, though. It’s a matter of record that the elaborate carvings of the chapel are full of Templar symbols. These include the most distinctive emblem of the Order, the image of two riders on a single horse, as well as an assortment of emblems the Templars shared with other medieval monastic orders. It’s also very much worth noting that four miles east of Rosslyn Chapel is the village of Temple.

The name is not an accident. Seven centuries ago, when it was called Balantrodoch, that same village was the headquarters of the Order of Knights Templar in Scotland.200 Wherever else in Scotland Knights Templar may have been in 1307, there were certainly some in the vicinity of Rosslyn Chapel, and those will have included the officials in charge of the Order’s Scottish presence, among others. If the legacy of the Knights Templar survived anywhere in Scotland, in other words, the vicinity of Rosslyn Chapel would be an excellent place to look for its traces.

The Dolorous Blow

The last link in the chain of connections I’ve attempted to trace here connects surviving Knights Templar in Scotland with the first lodges of Freemasons in the same country. That some connection must have existed is hard to dispute, as nothing else will explain the fact that Freemasons in the middle of the eighteenth century knew about a tunnel under the Temple Mount that was excavated at the time of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem in the twelfth century and not rediscovered until 1968. That the connection will be difficult to document is just as certain, for nothing else will explain the failure of generations of researchers to turn up more than the most equivocal evidence for the connection.

There were very good reasons for the heirs of the Templar secrets, whatever those may have included, to keep a very low profile during the years between the dissolution of the Order in 1311 and the emergence of Freemasonry as a public phenomenon in 1717. That period of four centuries saw Christian Europe turn on itself in a cascade of violent persecutions and religious wars as brutal as any in history. During those four centuries, anyone suspected of unpopular religious opinions risked being accused of heresy, seized by the local religious authorities, tortured until he or she confessed, and put to death. Anyone suspected of unapproved religious practices ran an equal risk of being accused of witchcraft and treated the same way.

When the Reformation burst on the scene in the first half of the sixteenth century, and Europe cracked asunder into hostile Catholic and Protestant blocs, the situation became even worse. All through Protestant Europe—and Scotland, it bears remembering, was well over on the radical wing of the Protestant camp—anything too reminiscent of medieval Catholicism was the target of savage reprisals. Monasteries and the orders that ran them were among the first targets, and throughout Protestant Europe, the entire monastic system was destroyed before the sixteenth century was over.

The dissolution of the monasteries in England is among the better documented examples.201 There the government of Henry VIII began closing down smaller monasteries in 1535, and the pace accelerated thereafter; by the end of 1541, every monastery and nunnery in the kingdom had been seized by royal officers, its monks or nuns driven off, its libraries and relics hauled away as trash, its buildings left to crumble into ruin, and its lands sold off to local landowners—at prices well below market rates, curiously enough, even though Henry VIII’s government was perpetually short of money. The same drama was played out everywhere in Protestant Europe over the course of the sixteenth century. In the process, in all probability, one of the main repositories of the temple tradition disappeared forever.

The situation in Catholic countries was less brutal but no less destructive to what remained of the temple technology. In response to the rise of Protestantism, the Catholic Church imposed a uniform set of rituals, the Tridentine Rite, on the entire church: the first time in the entire history of Christianity that anything like this had ever been done.202 The rich diversity of medieval rites and ceremonies—in the words of one ecclesiastical scholar: “every country, every diocese, almost every church throughout the West had its own way of celebrating Mass”203—gave way to a strictly enforced uniformity.

For almost four hundred years thereafter, under the watchful eyes of a newly founded bureaucracy, the Sacred Congregation of Rites, Catholic priests throughout the world spoke exactly the same Latin words and performed exactly the same actions. Even so simple and apparently harmless a project as translating the text of the Mass out of Latin, so that members of the congregation could understand what was being said, was strictly forbidden—vernacular translations of the Mass were on the Catholic Church’s Index of Forbidden Books until 1897. Monasteries were as subject to the new comformism as any other activity of the Catholic Church, and local traditions and customs were swept away in favor of a strict obedience to the dictates of officials from Rome.

The hypothesis at the core of this book would suggest that when such measures were put into place and the temple technology stopped being used across most of Europe, the result would be a significant decrease in agricultural productivity—and that’s exactly what happened. Historians noted a long time ago that many regions of Europe were more fertile in the Middle Ages than they are today. In upland regions across Europe, it’s not at all uncommon to find abandoned villages that were once thriving agricultural communities, where the only thing that grows today is sparse forage for sheep or goats.

Until recently it was thought that the European climate in the Middle Ages was much warmer than it is today. Recent research by climatologists, however, has shown that the supposed Early Medieval Warm Period never happened, and the European climate in the Middle Ages was not significantly warmer than it was in more recent centuries.204 The fact remains that something made it possible during the Middle Ages for wheat and barley to be grown on bleak uplands in Yorkshire and for wine grapes to flourish across southern England. Whatever that “something” was, it went away as the Middle Ages ended, leaving Europe struggling to feed itself—a struggle that played a large role in driving mass emigration from Europe to the New World and Australasia over the three centuries thereafter.

Was the collapse of the ancient temple technology the Dolorous Blow that, just as in the legends of the Holy Grail, caused a Waste Land to spread where crops and villages once flourished? Considerably more research will be needed before that question can be answered conclusively, but the possibility can’t be dismissed out of hand.

From Templars to Freemasons

With the monasteries gone or reduced to strict theological conformity, and a harsh spirit of religious repression and violence abroad throughout late medieval Europe, the remaining custodians of the temple tradition faced an uphill fight. Exactly how that struggle unfolded and how the tradition itself came to be lost will probably never be known for certain. Little evidence on the subject survives from the four centuries that separate the last known Templars from the first Masonic Grand Lodge and much of what has been discovered has too often been interpreted in unhelpful and implausible ways.

Some theorists who have explored the possibility of a link between the Knights Templar and the Freemasons, for example, have painted this connection in grandiose colors, imagining whole armies of Templar knights fleeing to Scotland with the Ark of the Covenant, the Holy Grail, and the mummified body of Jesus of Nazareth in their baggage. There’s precisely no evidence for any such mass migration—to say nothing of the relics in question!—and there’s also no need to posit anything so overblown. There were already Knights Templar in Scotland in 1307, some of them at the village of Balantradoch four miles from the hill where Rosslyn Chapel would one day rise, others in the many other properties owned by the Templar order across the Kingdom of Scotland.

The transmission of Templar traditions to Scottish lodges of operative stonemasons could have involved only a few Scottish Templars, or even just one. It’s not at all difficult to imagine a Templar brother trained in the builder’s art, say, whose experience helping to construct churches and chapter houses for the order in Scotland gave him the knowledge and skill to earn a place in an operative lodge, and who then passed on some of what he knew to his own apprentices and to other members of the guild. Even so slender a connection would account for the fact that Masons knew about the secret tunnel into the Temple Mount in Jerusalem two centuries before its rediscovery.

The question that remains is what else might have passed from surviving Knights Templar to the operative lodges. If, as I’ve suggested, the Templars may have learned some form of the ancient temple technology in the Holy Land, it would have been logical for them to have applied it to their vast landholdings across Europe, since the income from the agricultural production in those holdings helped pay the substantial costs of maintaining the Templar fortresses and armies in the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. If, as suggested in an earlier chapter, the Templar version of the temple tradition was connected to heretical beliefs akin to those of the ancient Naassenes, that connection would have made the heirs of the Templars all the more likely to try to preserve the temple technology as a sacred knowledge connected to their most deeply held beliefs. The question is how they might have tried to do this.

One possibility—though it is only a possibility, and a great deal of further research will be needed to confirm or disprove it—is that the building of Rosslyn Chapel may have been an attempt to construct a working example of the old temple technology. By the time the cornerstone of the chapel was laid, 135 years had passed since the formal dissolution of the Templar order, and whatever scraps of knowledge might have been passed on from former Templars to their heirs would have had ample time to be assembled and understood by the operative Masons who inherited it. William Sinclair, Earl of Caithness, the builder of the chapel, was also the patron and titular grand master of stonemasons in Scotland, a title that remained in the Sinclair family for centuries thereafter. If anyone in fifteenth-century Scotland was going to try to revive the temple technology, Sinclair was the man.

If that was the purpose for which Rosslyn Chapel was built, though, it failed. Once the Reformation got under way in Scotland, Rosslyn Chapel was among the targets of Protestant rage. In 1592, officials of the Presbyterian Church ordered the altars of the chapel demolished and put an end to services there. In 1650, during the English Civil War, the chapel was used by Roundhead soldiers as a stable for their horses, and in 1688, a Protestant mob from Edinburgh diverted themselves after looting and burning Roslin Castle by doing more damage to the already battered chapel. After that it sat empty and abandoned, a windowless ruin. Whatever secrets might have gone into its construction, whatever traditional practices might have taken place there, were lost forever.

Not until 1736 did matters begin to change. In that year, the last Sinclair to hold the title of grand master of Scottish stonemasons, another William Sinclair, formally resigned it in favor of the first grand master of the Masonic Grand Lodge of Scotland. In the same year, John St. Clair, the owner of the dilapidated ruin of Rosslyn Chapel, repaired the damaged roof, put new flagstones on the floor, and filled the empty windows with new glass. He was urged to do this by Sir John Clerk of Penicuik. It’s probably not a coincidence that 1736 was also the year in which the Masonic Grand Lodge of Scotland was founded, and Clerk was one of the most prominent Scottish Freemasons of his day.

By that time, though, whatever secrets might have been passed down from the Templars to the operative lodges had apparently been lost. Exactly how that happened will probably never be known. Secret teachings are fragile things; the fewer the people who know them, the more likely they are to become garbled or forgotten. In the tremendous political, religious, and social convulsions that swept over Scotland in the seventeenth century, it would have been all too easy for the thread of tradition to snap. A few stray bullets in the many battles of the time, a few of the many political executions in those years, or simply a climate of opinion that made passing on a heretical religious teaching too dangerous to risk would have been enough.

Even so, there’s some reason to think that Masons in the early eighteenth century still retained a last flickering memory of the Templar secrets. This is suggested by a curious passage in the very first exposé of Masonic high degrees, Les Plus Secrets Mystéres de la Hautes Grades de la Maçonnerie Dévoilés (The Most Secret Mysteries of the High Degrees of Masonry Unveiled), published in 1766. In this passage, the origin of Masonry is traced back to Godfrey de Bouillon, the leader of the First Crusade, who supposedly invented the symbols of Masonry so that the Crusaders could conceal the fact that they were Christians from their enemies.205 As literal history, this is nonsense, and the passage gets even stranger when it claims that Godfrey de Bouillon was the leader of the Crusaders “toward the end of the third century,” which makes no straightforward sense no matter how it’s interpreted.

If “Godfrey de Bouillon” is a cover for some other more secret name, though, the passage makes a great deal of sense. The Naassenes, as already mentioned, believed that “of all men we alone are Christians, accomplishing the mystery at the Third Gate.” Once the Catholic Church gained ascendancy in the western world, Naassenes would have been in exactly the position of the imaginary Crusaders in the passage just cited, forced to conceal their religion from hostile believers in a different faith, and the camouflage of Masonry would have been a plausible way for them to do so. That this happened in the third century of the Common Era seems vanishingly unlikely, but then it’s anyone’s guess what date would have served as the starting point for the calendar of a medieval Gnostic heresy descended from, or related to, the Naassenes. “The third century” from that starting point could have been almost anywhere from the early Middle Ages to the early modern era.

There is at least one other piece of evidence, furthermore, that the lost secrets of Masonry had a connection to alternative religious beliefs—the frantic hostility the Catholic Church has directed toward the Craft, mentioned back in Chapter One, is one of the enduring oddities of Masonic history. Factor in the history described in Chapter Eleven and Chapter Twelve, though, and the riddle becomes clear at once. If, as I’ve suggested, the Templars embraced the old temple tradition along with a heresy that was either the Naassene gnosis or something more or less parallel to it, Catholic authorities would have become aware of that once Templar properties were handed over to the church, if they had not been aware of it long before.

When Freemasonry turned up with symbols obviously derived from the same tradition, in turn, the logical response of Rome would have been exactly what in fact happened. This link to ancient heresy, I suggest, explains the unnamed and unexplained “just and reasonable motives known to us” mentioned in the papal bull In Eminente better than any alternative. That the Freemasons themselves had lost the teachings for which they were condemned so harshly is just one of history’s many ironies.

What remained then, and what remains today in Masonry, is a collection of beautiful but enigmatic ceremonies and symbols, pervaded by a traditional sense that these things were once the keys to a tremendous secret. Then as now, the men who became Freemasons were taught that the words and signs they were given were substitutes for something else and encouraged to look forward to the day when the true secrets of a Master Mason would once more be revealed. It may well be that the brothers who founded the first Grand Lodge of England in 1717 and the Grand Lodge of Scotland in 1736 hoped to recover those lost secrets.

If so, those hopes were not fulfilled. Freemasonry evolved in different directions, away from the studies that might have revealed the temple technology, and toward its present role as a men’s social club with ornate initiation ceremonies and a variety of praiseworthy charitable commitments. To this day, Masons continue to confer degrees that hint at a lost secret, preserve symbols that none of the Craft know how to interpret, and scatter grain and pour wine and oil on cornerstones—a fragmentary survival, perhaps, of ancient ceremonies that once linked certain buildings to a technology of agricultural fertility. Only these mute fragments of the lost operative knowledge remain, the last fading echo of an ancient mystery.

192 See Partner 1981 for a crisp exposition of the consensus view.

193 Robinson 1989.

194 Ben-Dov 1985 describes the tunnel’s discovery.

195 These are the Francken Manuscripts, the foundational manuscripts of the Scottish Rite. See de Hoyos 2015.

196 See Ralls 2003, 145–50, for a summary of these earlier expeditions.

197 Ralls 2003, 181.

198 Butler and Ritchie 2013, 183–184.

199 Butler and Ritchie 2013, 216–218.

200 Lord 2013, 186–191.

201 See Youings 1971 for a good summary.

202 Jones et al. 1992, 285.

203 Jones et al. 1992, 286.

204 See, for example, Lemonick 2014.

205 de Hoyos and Morris 2011, xvii-xx.