The Temple of Solomon

In the seventh year of his reign, according to the first book of Chronicles, King David captured the city of Jerusalem from the Jebusites, the Canaanite nation that had possessed it since time out of mind. Once the city was in Israelite hands, David moved the nation’s capital there from Hebron and built a palace. Just north of the little walled city was a flat-topped hill owned by Ornan the Jebusite, who used it as a threshing floor—an outdoor space where grain was pounded with flails and then tossed in the air with a pitchfork so the grain fell straight down while the chaff went drifting away on the wind. Years after the conquest of the city, in response to a pestilence, David bought the hill from Ornan for fifty shekels of silver and built an altar there to make offerings to the God of Israel.

Some thirty centuries later, the threshing floor atop that flat-topped hill—or, more precisely, the vast complex of ruins built over and around the hill—is known to Jews and Christians as the Temple Mount, to Muslims as al-Haram al-Sharif, “the Noble Sanctuary,” and to people around the world as one of the most intractable flashpoints in the bitter tensions between the nation of Israel and the Arab countries that surround it. This is nothing new in the Temple Mount’s history. Over and over again since David’s time, the mount and the sacred buildings raised upon it have been the focus of every kind of struggle and atrocity that religious, political, and ethnic passions can generate.

The symbols and rituals of Freemasonry include a great many references to the Temple Mount, the structures that have been raised and destroyed atop it, and the underground tunnels and vaults that traditionally lie beneath it. To understand the secret that may still lie hidden in Freemasonry’s fragmentary traditions and enigmatic rituals, a glance back over the history of the Temple Mount will be crucial.

That history actually begins far to the south of the threshing floor of Ornan, on the slopes of Mount Sinai. According to the book of Exodus, that was the place where Moses received from the God of Israel a set of detailed instructions for the building of the first Jewish sanctuary, the Tabernacle. This was a sacred tent made of linen, divided by curtains into an inner sanctum, an outer space of lesser holiness, and a porch in front. The tent was surrounded by a screen of cloth supported on wooden poles, and inside the screen but outside the tent were a portable altar for sacrifices and a basin of water for purifications. Three chapters of the book of Exodus are given over to a painstaking description of the Tabernacle and its furnishings—detailed enough that more than one complete modern copy has been made.

To this day, nomadic peoples in various corners of the world have similar sacred tents, which they set up for worship and then take down and load upon their horses or camels when it’s time to move to the next campsite. During their wandering years, the Israelites did much the same thing with the Tabernacle, and even after they settled down in what had previously been the land of Canaan and took up agriculture, the Tabernacle remained a center of Israelite worship for many generations. Only in the wake of sweeping political and cultural changes did it give way to a more permanent structure, the famous Temple of Solomon.

The First Temple

Open-air altars and sanctuaries of the sort King David established on Ornan’s threshing floor were common all over the Middle East during the lifetime of that monarch and for centuries before and after his time. The Old Testament refers to them as “high places,” as they were generally established on hilltops or other elevated locations. The Hebrew people had worshipped at such places for centuries before the First Temple was built. After the Hebrew conquest of Canaan under Joshua, as already noted, the Tabernacle remained a center of Hebrew piety, but it shared space in the religious life of the people with local high places, not all of which were consecrated to the God of Israel.

David and his son Solomon reigned during an era of centralization, when the eastern Mediterranean basin was in transition from a patchwork of independent tribes and city-states to a land of great kingdoms, and eventually of empires. One visible mark of that transformation was the emergence of the national temple: a holy place located in the capital of each kingdom, to which people from around the kingdom were expected to make pilgrimage and bring offerings at certain times of the year.

The Hebrews, as former nomads whose technology and culture lagged behind those of most of their neighbors, were latecomers to the process of centralization as well. Long before the Israelite tribes accepted their first king, Saul, powerful kingdoms and national temples were rising elsewhere in the region. When Solomon ordered work to begin on a national temple for the kingdom of Israel, therefore, one of his first actions was to bring in foreign craftsmen from the country of a more technologically and culturally complex ally.

According to the biblical accounts, the ally was Hiram, king of the thriving seaport of Tyre in what is now Lebanon. Hiram Abiff, the Tyrian master craftsman who plays so important a role in Masonic symbolism, was among the craftsmen the King of Tyre sent. These skilled workmen brought with them the knowledge obtained by generations of master builders in the eastern Mediterranean basin, and unsurprisingly, the temple they built for Solomon had a great deal in common with other national temples in the region.20

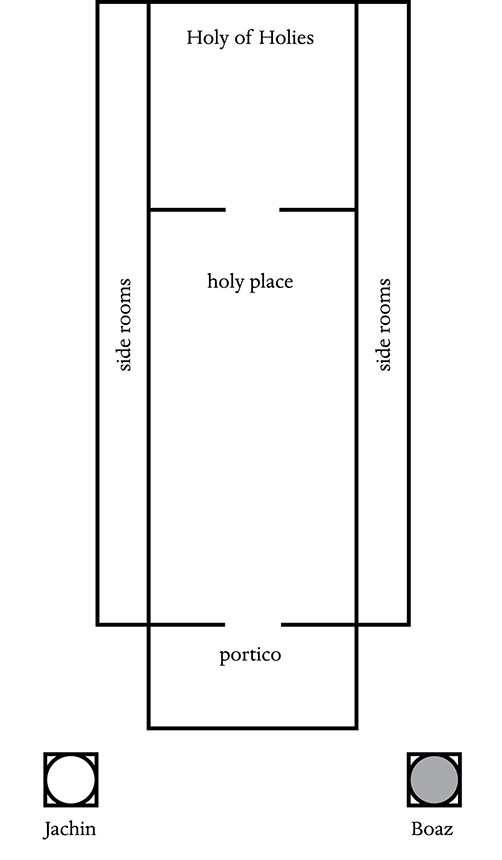

The first thing that needs to be grasped in making sense of the Temple of Solomon is just how small it was: only about ninety feet long, thirty feet wide, and forty-five feet high.21 Like the Tabernacle, the temple was divided into three parts—a porch (in Hebrew ulam) on the eastern end, some fifteen feet deep; the main room inside, the holy place (in Hebrew heikal), sixty feet long; and the debir or Holy of Holies at the western end, a perfect cube thirty feet on a side. To either side of the temple proper were narrow rooms used by the priests for storage and other purposes; see illustration on page 29.

Both the heikal and the debir were paneled with sheets of pure gold. The Ark of the Covenant, a wooden chest covered with gold that contained the most sacred treasures of the Jewish people, was kept inside the Holy of Holies under the wings of two wooden cherubim likewise covered with gold. In the main room were the sacred seven-branched candlestick, the altar of incense, and the table of shewbread, on which loaves of bread were placed as offerings.

Out in front were two huge pillars of brass, named Jachin (Hebrew for “he shall establish”) and Boaz (“in strength”). Scholars disagree about whether they were part of the porch or freestanding structures; in either case, they were substantial—according to 1 Kings 7:15–22, they were 27 feet high; according to 2 Chronicles 3:15–17, their height works out to 47 feet 6 inches, and according to both sources, each pillar had a bronze capital on top, adding an additional 7 feet 6 inches to the total. In the courtyard in front of the temple was the so-called “brazen sea,” a huge brass basin of water used for purification, and an altar of sacrifice, where animals were slaughtered as offerings to the God of Israel.

The biblical description is all that survives of the Temple of Solomon. The very limited archeological research that has been permitted on the Temple Mount in modern times has turned up no single physical trace of it, and in fact evidence for the Hebrew kingdoms of Judah and Israel before the Babylonian conquest is very thin on the ground. Much has been made of this dearth of hard data in some circles, but the same shortage of evidence applies equally well to most of the little kingdoms of the ancient Near East.

A few good archeological sites in the region, a few caches of documents in Egypt and elsewhere, and the twist of fate that turned the traditional histories of one of the little kingdoms of that era into the holy scripture of one world religion and the Old Testament of another provide the little information about the First Temple that today’s scholars have to go on. Not until the Temple of Solomon was leveled to the ground and a new temple rose in its place does documentation become more complete—and it is at this point that the inquiry central to this book finds its starting place.

The Second Temple

In the year 586 BCE, as commemorated in several of the Masonic rituals described in chapter 1 of this book, a Babylonian army besieged and captured Jerusalem, destroyed the city and the temple, and deported its population. In 539 BCE Babylon fell in its turn to the armies of Cyrus, king of Persia. Among the new ruler’s first acts was to terminate the Babylonian policy of deporting conquered populations, and the Jews were among the beneficiaries.22 Many of the exiles returned to Jerusalem, and under the leadership of their prince Zerubbabel, they began the long and difficult process of building a new city and temple on the ruins of the old. Despite political troubles with the Persian authorities and conflicts with the local population, the new temple was completed in 516 BCE.

The Second Temple, as this structure is called, was built on the pattern of the Temple of Solomon, and in all likelihood on the same foundations. It was a considerably less lavish structure than its predecessor had been—Solomon’s temple was the focus of worship for an independent and prosperous nation, while the Second Temple was merely one of many ethnic religious centers in a huge and polyglot empire. The gold that played such a massive role in Solomon’s temple was in considerably shorter supply in Zerubbabel’s, though Cyrus ordered the return of the temple furnishings that had been looted by the Babylonians and presented as trophies of victory to the temples of Babylonian gods.

Certain things present in the Temple of Solomon were absent in the Second Temple. The most important of them was the Ark of the Covenant, which apparently did not survive the Babylonian conquest—there is no record of it in the Bible or any other written source after that point. Throughout the history of the Second Temple, though the traditional furnishings of the heikal (main hall) were recovered or replaced, the debir (Holy of Holies) was empty. The two pillars Jachin and Boaz, which came to play such an important part in Masonic symbolism later on, were also missing in the time of the Second Temple. There is no discussion of the reason for their absence; they simply weren’t replaced.

The new building campaign brought considerable changes to the Temple Mount. The Babylonians apparently tore down the retaining walls and left behind only a mass of rubble. The builders of the Second Temple rebuilt the retaining walls, making the Temple Mount larger than it had been in Solomon’s day. According to the Letter of Aristeas, one of the few surviving writings that describe the Second Temple before the time of Herod, the rebuilding also involved putting in drainage channels for the blood from sacrificed animals and a network of cisterns and tunnels that provided an ample supply of water for priestly use.23

The Temple of Herod

Zerubbabel’s temple remained the center of Jewish religious life for well over four centuries. Toward the end of that time, it had become something of a national embarrassment, a small and shabby building in an age of great architecture. That was the situation when Herod the Great became the king of Judea. Herod was not even Jewish in origin—he was an Idumaean, from the eastern side of the Jordan valley—but he was a supremely talented politician. When King Antigonus II of Judea tried to shake off Rome’s overlordship with the help of the Parthians farther east, Herod managed to get himself appointed king of Judea by the Emperor Augustus, and conquered the country with Roman help.

He then set out to conciliate his new subjects by rebuilding the Temple Mount complex on the grandest scale possible. This was a complicated project, not least because worship and sacrificial offerings had to continue on the site straight through the rebuilding process—this is why, in Jewish tradition, the temple of Herod isn’t considered the third temple but counts as a continuation and expansion of the second. Difficult as the project must have been, Herod accomplished it with aplomb, and the temple and its surrounding courtyards, porches, and buildings counted thereafter among the architectural wonders of the ancient world.

The whole complex covered some 36 acres, surrounded by massive retaining walls topped by porticoes supported by a forest of Corinthian columns. This was a huge area by the standards of the age, twice as large as the Forum in Rome and more than four times as large as the Acropolis in Athens. Inside the greatly expanded Temple Mount, additional cisterns, drains, and channels for water were built, along with underground storage rooms for priestly use. Ten gates in the retaining walls, with tunnels behind them, provided access to the Temple complex.

The largest of the porticoes, on the south, was where the moneychangers had their booths—Jews from around the Mediterranean world came to the temple and were expected to pay a temple tax in the local currency. Inside the porticoes, courtyards divided the Temple Mount into areas with progressively more restricted access—the Court of the Gentiles, the Court of the Women, the Temple Court, and the Court of the Priests, surrounding the temple itself.

Herod’s temple used the same foundations as the temples of Solomon and Zerubbabel but placed a massive facade in front, a hundred cubits high and wide—that is, around a hundred and fifty feet each way. The side rooms were greatly expanded, and an upper story was added atop the heikal and debir, with rooms accessible by a spiral staircase in the temple’s northeast corner. The whole structure was faced with white limestone and sheets of gold, which must have shone brightly enough to hurt the eyes when the sun rose and sparkled on the eastern facade.

The rebuilding project got under way in 20 BCE, and work was still proceeding on some of the outlying parts of the complex when the Jewish revolt against Rome in 66 CE made the whole point moot. When the city fell to the Romans in 70 CE, the temple was demolished. After a second revolt in 132 CE, the Temple Mount itself was systematically destroyed, the upper sections of the retaining walls toppled over into the valleys to either side, and a temple to Jupiter built atop the ruins. That was leveled in its turn when the Roman Empire was Christianized in the fourth century CE, and from then until Jerusalem was conquered by Muslim armies in 638 CE, the Temple Mount was a ruin.

The destruction of the temple has been a central theme of Jewish thought and practice ever since the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE. Among the immediate consequences of that national catastrophe was the creation of the Mishnah, the compilation of scholarly tractates that forms the core of the Talmud. Much of the material included in the Mishnah consists of details of the temple and the ceremonies that were practiced there,24 and cherished memories of the temple and lamentations for its loss appear all through the Mishnah and its commentaries. Curiously, though, one of the things most fondly remembered and most bitterly lamented was the temple’s power to make crops flourish.

The Temple as a Source of Fertility

Perhaps the strangest thing about the Temple of Jerusalem, in fact, is the traditional insistence that it was a source of agricultural fertility. The accounts of the temple and the temple service in the Mishnah testify to this in no uncertain terms:

And so you find that all the time that the service in the Temple was performed, there was blessing in the world, and the prices were low, and the crop was plentiful, and the wine was plentiful, and man ate and was satisfied, and the beast ate and was satisfied, as it is written: “And I will send grass in thy fields for thy cattle that thou mayest eat and be full.”25

Over and over again, in the Talmud and other collections of Jewish tradition and folklore, the temple is held to have functioned as a source of fertility. The rock on which the temple stood, at the heart of what is now the Temple Mount, was believed to be the first solid land created by God, around which the rest of the world took shape. Far beneath it lies the Tehom, the primal abyss of waters that rose up during the flood, and subterranean channels spread out in every direction from the Temple Mount to every part of the world, giving each country the power to grow its proper agricultural products.26

The functions of the Temple were believed to extend even to weather modification. Before the Temple was built, according to a Talmudic midrash (commentary) on the book of Genesis, torrential rains fell on the land of Israel for forty days each year, causing great destruction.27 The erection of the Temple of Solomon put an end to the torrents. When the Second Temple was destroyed, the torrents did not return; instead, the south wind, which used to bring rains while the temple stood, ceased to do so and has never brought rains since that day.28

According to the Talmud, the destruction of the temple cut off all the structure’s beneficial influences on soil and weather and was therefore a disaster not only for the Jews but for every people in the world: “Rabbi Joshua ben Levi said: Had the nations of the world known how beneficial the Temple is to them, they would have surrounded it by camps in order to guard it.”29 The prophesied restoration of the temple in the time of the Messiah, in turn, is expected to bring about an extraordinary change in the world: twelve streams of water will rush forth from underneath the Temple Mount and flow in all directions, and these will cause even barren fields and vineyards to bear fruit.30

An interesting disagreement between different accounts of the temple’s miraculous effect on fertility relates to the actual source of those powers. According to some Jewish legends, the powers exercised by the temple centered on the Ark of the Covenant, which is called the Life of the World in these accounts. So powerful was the Ark, claimed one story, that when it was first brought into Solomon’s Temple, the very cedar beams of the structure became green and brought forth fruit.31

Yet the fertilizing powers of the temple were held to have resumed as soon as the Second Temple was built. In the second chapter of the book of Haggai, the prophet asks the people rhetorically how they fared “before a stone was placed upon a stone in the Temple of the Lord”; the answer, of course, was that they had lived under the constant threat of famine, but since the laying of the cornerstone of the Second Temple, the fertility of the land had improved dramatically.32 This is all the more startling in that, as we have seen, the Ark of the Covenant was long lost by the time the exiles returned from Babylon and began work, and the Holy of Holies of the Second Temple, throughout its history, contained nothing at all. In this tradition, at least, it was not the Ark that brought fertility to the land of Israel, but the temple itself.

Here, as elsewhere, it’s crucial not to reduce the richness and complexity of human religious life into any single factor. The Temple of Solomon and its successive structures had many different roles in the life of the ancient Jews, and the most important of them were religious in the same sense that word generally has today—that is, the temple was a place where Jews prayed to the God of Israel, sought his forgiveness for their sins, and invoked his blessings on every aspect of human life. The temple was a spiritual phenomenon first, in other words, and its relation to fertility came second to that.

Agricultural fertility was only one of the many things that people prayed for when they went to the temple to make offerings or simply faced it from a distance in order to pray to the dwelling place of God on earth. Agricultural fertility was also only one of the miraculous things that are said to have occurred while the temple was still standing; for example, a number of Jewish legends and certain passages in the Old Testament33 claim that at certain times the temple became filled with a luminous cloud so brilliant and blinding that the priests could not perform their duties.

Thus it’s fascinating that Jewish legend and tradition place so much repeated emphasis on the temple as a source of agricultural fertility, as distinct from its other religious functions and traditional miracles. What makes this focus all the more curious is that elsewhere in the world, wherever temples of a design more or less similar to the Temple of Solomon were in use, traditions assign them a similar power. As we’ll see, there are reasons to suggest that there may be an unexpected reality behind these remarkable parallels.

20 See Lundquist 2008, 46–70.

21 The measurements cited in the Old Testament are 60 cubits in length, 20 in width, and 30 in height; the exact length of the cubit used in the building has been disputed, but it was somewhere around 18 inches.

22 This decision of Cyrus is documented outside the Old Testament; see Lundquist 2008, 71–72.

23 Lundquist 2008, 83–84.

24. Lundquist 2008, 130.

25 Cited in Patai 1967, 123; the Scriptural quote is from Deuteronomy 11:15.

26 Patai 1967, 85–6. I have cited Patai’s book here as an accessible English language source on the Talmudic literature concerning the traditional lore surrounding the Temple.

27 Ibid., 121.

28 Ibid., 125.

29 Cited in Patai 1967, 127.

30 Ibid., 88.

31 Ibid., 91.

32 Lundquist 2008, 76.

33 See, for example, I Kings 8: 10–11.