The Changing of the Gods

Most versions of the temple tradition surveyed in the previous chapter belong to faiths that have passed through many centuries of eclipse. Hindu temples and Shinto shrines still thrive, to be sure, and not only in their original homelands, while here and there individuals and small groups are struggling to resurrect the ancient faiths of Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Between these surviving or revived traditions and their ancient equivalents, though, lies an immense and almost wholly unexplored historical transformation—a religious revolution whose echoes still resound through the thinking of much of the modern world.

Though its implications are vast and complex, the revolution itself is simple enough to describe. Beginning around 2,500 years ago, most people in literate societies across the Old World stopped worshipping the old gods and goddesses of nature and started revering abstract creator gods and dead human beings instead. The first stirrings of this religious revolution were in Persia, where Zarathustra preached the gospel of the one god Ahura Mazda sometime in the second millennium BCE, and Egypt, where Akhenaten’s short-lived solar monotheism had its day between 1370 and 1350 BCE. In India, the religious revolution got started around 500 BCE and is associated with the names of Siddhartha Gautama, later known simply as the Buddha, and Mahavira, the founder of the Jain faith; in China, the relevant name is that of Zhang Daoling, who transformed Taoist philosophy into an ascetic religion in the second century BCE; farther west, the names of Jesus and Muhammad are the most widely known figures of this kind.

Even those religions that stayed more or less intact through the great transformation underwent massive change. Judaism is a particularly relevant example here. The scholar Raphael Patai has argued on the basis of a great deal of evidence that the Jewish faith did not become monotheistic until the aftermath of the Babylonian captivity (586–539 BCE) when it absorbed important influences from Persian Zoroastrianism and rewrote its sacred scriptures to suit.

Patai demonstrates that the official religion of the Israelites during the era of the First Temple included the worship of two goddesses as well as the God of Israel in addition to many of the same rites and customs—many of them oriented toward agricultural fertility—as their Caananite neighbors.64 In the wake of the religious revolution, the goddesses were expelled from the religion and their worship redefined in retrospect as the terrible sin for which the nation of Judah was destroyed. Meanwhile the God of Israel himself underwent a change at least as drastic—from the crusty tribal deity of the Old Testament’s earliest strata to an abstract creator of the cosmos whose special relationship with one small Middle Eastern people landed later theologians in any number of perplexities.

Gods of Life, Gods of Death

Though the revolution centered on a change from worship of nature deities to reverence for prophets and saints, it had broader implications. One of these involved a complete reversal in attitudes toward nature, sexuality, and biological existence. In religious festivals in ancient Greece, large wooden penises were paraded down the streets as emblems of the abundant life and joy the gods of nature brought into the world without anyone being the least embarrassed by the custom. You can find nearly identical wooden penises being paraded through the streets of Japanese towns during some Shinto festivals today, in exactly the same spirit. To the prophets and heirs of the religious revolution, by contrast, the idea of sexual delight as a divine gift to be celebrated in public was unthinkable. Holiness, to them, required the renunciation of sex, not its celebration; at most, it might be grudgingly permitted for the sake of reproduction, but never enjoyed and never treated as sacred.

At the same time, attitudes toward death and the corpses of the dead underwent an equal and opposite reversal. Though there were exceptions—the ancient Egyptian cult of the dead comes to mind—most of the old nature religions had very strong taboos concerning contact between dead things and holy things. To bring a corpse into an ancient Greek temple would have been the kind of impious act that would leave devout pagans waiting for Zeus to throw a thunderbolt. In exactly the same way, nothing connected with death can be brought into a Shinto shrine to this day without rendering the place and everyone involved in that act dangerously impure. The new prophetic religions, by contrast, gave the relics of the dead a central role in their theology, their ceremonial life, and above all in their architecture. Christian churches from before the Reformation are thus surrounded by churchyards full of tombs. Sites where some part of the Buddha’s body is enshrined are among the core holy places of Buddhism, while the tombs of Sufi shaykhs attract the devotion of many Muslims.

Similar changes reshaped attitudes to every other aspect of biological existence. In the old temple cults, priests and priestesses might fast from specific foods and abstain from sexual activity during certain periods in order to attain a state of ritual purity appropriate for some special ceremony. After the religious revolution, by contrast, these customs were applied to the whole of life, backed up by the insistence that anybody who failed to abide by what were once priestly disciplines of ritual purity would be tortured in the afterlife for their sins.

More broadly, where life in its full, richly biological reality was central to the older worship of the deities of nature, the prophets of the religious revolution turned their backs on life—in that robust sense—to focus attention on an idealized otherworld on the far side of death. The Buddhist insistence that life is suffering, the Christian devaluation of physical existence in favor of the imagined delights of heaven, and equivalent rhetorical strategies in other prophetic faiths all flow from and feed into the rejection of concrete biological life that defined the new vision.

It’s important to realize that the transformation we’re discussing was not some kind of universal shift in consciousness, which certain modern theorists like to imagine. While it spread over much of the Old World, its reach was never total. In sub-Saharan Africa, many nations retained their traditional religions in spite of pressure from missionaries of prophetic faiths; in Japan, political factors forced one of the new faiths to accept the persistence of an older tradition; in India, although Buddhism swept all before it in the centuries immediately after the Buddha’s time, the tide turned in the fifth century CE, and thereafter Hinduism resumed its place as the dominant religion on the Indian subcontinent.

In the New World, the new faiths had no presence at all until imported at European gunpoint after 1492. Legends surrounding the career of the Toltec prophet-king Ce Acatl Topiltzin, who reigned in the tenth century CE and was later identified with the gods Kukulcan and Quetzalcoatl, suggests that an attempt at something like the Old World’s religious revolution may have taken place in Mesoamerica. If so, however, its legacy was quickly reabsorbed into the existing framework of native Mesoamerican religion.

The causes and consequences of this massive changing of the gods could occupy a much larger book than this one. For our present purposes, though, the relevant point is the impact that the religious revolution had on the temple tradition sketched out in previous chapters. Wherever the temple tradition existed in ancient times, it had become deeply interwoven with the old religions of the gods and goddesses of nature. The prophets and apostles of the new religions accordingly denounced temples and everything done in them as an element of the old ways, which had to be brushed aside to make room for the newly revealed truth.

The entire matter might have ended there. In some places and times, it did end there. Orthodox Sunni Islam, for example, seems to have eliminated the temple tradition root and branch in the process of imposing its own distinctive religious vision on the lands where it predominates. Most branches of Buddhism have erased the tradition nearly as completely. Here and there, though, in the wake of the religious revolution, elements of the temple tradition crept back into some branches of the newly founded prophetic religions. We’ve already seen how esoteric Buddhism in Japan became a vehicle by which the temple tradition found its way into Shinto—although that story has further complexities, which will be detailed below. Processes of the same kind seem to have occurred elsewhere in a few other faiths, as people aware of the temple tradition’s secret technology worked out ways to combine the old practices with the new religions.

The most dramatic example of all took place in Western Europe. There, despite the bitter hostility dividing the local prophetic religion and the older, nature-centered faiths that it supplanted, the entire toolkit of the classic temple tradition seems to have found its way nearly intact into medieval Christianity. The process by which this transition took place was complex and involved at least two distinct processes of transmission—one of which, as we’ll see, left definite traces of its presence in the traditions of Freemasonry.

During the high Middle Ages, as a result of this complex history, Christian churches across Europe were built according to the same principles as the Pagan temples of an earlier time. Many of them, in fact, were built on the same locations, faced the same directions, and celebrated festivals on the same dates. So extensive were the borrowings from the temple tradition that accounts of medieval church design and ceremony—together with the churches themselves and the immense body of traditional folklore that gathered around them—are among the most important sources of information from which the overall pattern of the temple tradition can, however tentatively, be reconstructed.

The Zoroastrian Foreshadowing

A transformation of the same kind, by which the temple tradition was adopted for a time by one of the new prophetic religions, also happened in Persia in the fourth century BCE. Until that time, the Zoroastrian religion had no temples. Greek writers noted with amazement that their Persian adversaries worshipped without temples or altars, and the Zoroastrian scriptures take it for granted that the worship of the Zoroastrian god Ahura Mazda takes place in the open air.65

After the Persian conquest of Mesopotamia, though, the mother goddesses who had long been worshipped by the native peoples of the conquered lands became popular among their new Persian overlords as well. The Zoroastrian priesthood responded by finding a yazata (subordinate deity), the goddess Anahita, who more or less corresponded to Ishtar, Astarte, and the other great Mesopotamian goddesses, and permiting Mesopotamian styles of worship to be offered to her.66 Readers familiar with the history of Christianity will recall the way that worship once paid to Pagan goddesses in Europe was redirected into reverence for the Virgin Mary; the parallels with the rise of Anahita worship in Persian-occupied Mesopotamia are very close.

Along with worship of the yazata Anahita, the Zoroastrians in Mesopotamia seem to have adopted some version of the classic temple tradition, and this appears to have spread back into the Zoroastrian mainstream in Iran. The oldest known remains of a Zoroastrian temple at Seistan in southeastern Iran follow a plan that will be familiar to readers of this book. It was built atop an isolated hill and featured a large hall with a smaller square hall off one end, and beyond that a third space, smaller still, seems to have filled the role of Holy of Holies. The original temple probably dates to the third century BCE; it was rebuilt at least twice thereafter following the same plan.67

Whatever spiritual and philosophical compromises led to this fusion of Zoroastrian monotheist religion and the old temple tradition, though, the fusion itself did not endure. The great temples of the Zoroastrians were wrecked and abandoned after the Muslim conquest of Iran, and many of the more complex priestly practices went by the boards in the struggle to preserve the essential core of the Zoroastrian faith. When Zoroastrian communities in India and elsewhere established temples of their own in later centuries, those did not follow any version of the temple plan explored in the earlier chapters of this book. This trajectory of adoption and abandonment proved to be prophetic, for much the same thing happened in the Christian faith between the fall of Rome and the aftermath of the Reformation.

The Temple Tradition and Buddhism

As mentioned in Chapter Three , esoteric Buddhism seems to be the vehicle by which the temple tradition made its way to Japan. The presence of the temple tradition in any Buddhist source is surprising, to be sure. The Buddhist faith is focused on winning salvation for all beings from the wheel of rebirth and the suffering inherent in existence, and its early architecture focused on two kinds of structures unrelated to the temple: on the one hand was the monastery, which was simply a dwelling for monks, and on the other was the stupa, a structure containing a relic of the Buddha himself or a Buddhist saint, where the faithful gathered to pray, meditate, and circumambulate.

One complexity in tracing the temple tradition’s connection to Buddhism is that the original homeland of the Buddhist faith, India, returned to Hinduism in the early Middle Ages, and trying to piece together ancient and medieval Indian Buddhism from its surviving traces and the small Buddhist communities that remain in India itself is a very challenging process. Elsewhere in Asia, Buddhism very quickly picked up local architectural traditions among many other things; architecturally speaking, as a result, a Buddhist monastery in Tibet has almost nothing in common with a Buddhist monastery in Vietnam.

A second complexity is that the esoteric school of Buddhism, the branch that seems to have picked up the most information about the temple tradition, went extinct not only in India but in most of the rest of Asia as well. It remains active today mostly in Japan on the one hand and in Tibet and regions such as Mongolia that received cultural influence from Tibet on the other. Adding to the complexity is the fact that the Japanese and Tibetan versions of esoteric Buddhism are radically different from one another.

The literature on Tibetan Buddhism is immense, and only a small portion of it has been translated into any Western language. The sources available to me, however, have not shown any trace of the temple tradition in Tibetan Buddhism. There is some reason to believe, rather, that only the Japanese traditions of esoteric Buddhism had contact with the temple tradition—and that they got it from a surprising source.

The founders of esoteric Buddhism in Japan were two enterprising monks, Saicho and Kukai, who made what was then a long and difficult journey from Japan to the imperial Chinese capital at Chang-an in 804 CE. One of the leading Buddhist masters with whom they studied was an Indian monk named Prajna. Prajna is well known to scholars of Chinese religion as an important translator of Buddhist scriptures into Chinese, but he did not produce his translations alone. Rather, he worked with a Chinese-speaking Persian who had adopted the Chinese name Ching-ching and was a famous translator in his own right, as well as a bishop in the Nestorian branch of Christianity.68

The Nestorian Church is one of the forgotten success stories of early Christian history. In the year 431 CE, Nestorius, Patriarch of Constantinople, was deposed from his position by the Council of Ephesus for theological irregularities. Undaunted, he organized an alternative church in Syria. Persecution by the established church drove the Nestorians, as his followers came to be called, out of Roman territory into the rival Persian empire, where they became the most influential of the various Christian sects.

By 631 CE, the Nestorian movement had spread all the way across Asia to the Chinese Empire. Four years later, according to a famous monument in Chang-an, the emperor Tai-tsung reviewed the teachings of the Nestorian Church, found them acceptable, and authorized the newly arrived church to seek converts throughout the Chinese empire. The “Religion of Light,” as the Nestorian faith was called in China, gained a substantial following in the century or so that followed and was still a significant force in the Chinese religious scene when Saicho and Kukai arrived.

By the time he began working with Prajna, Ching-ching (Bishop Adam as he was also called) had already translated thirty books of Christian scripture and teaching into Chinese, including the Gospels, the epistles of Paul, and the Psalms. Saicho and Kukai both stayed in the Buddhist monastery in Chang-an, where Prajna and Ching-ching worked, then returned to Japan with copies of the seven volumes of Buddhist sutras the two men had translated. Then, after Saicho and Kukai established the two esoteric sects of Japanese Buddhism and cordial relations with the indigenous Shinto faith, shrines that appear to make use of the classic temple tradition suddenly became an important part of Shinto practice, replacing the open-air enclosures that had been standard up to that time.

The logical conclusion is that information about the temple tradition passed from Ching-ching to Saicho and Kukai and from them, by way of the schools they founded, to Shinto. Exactly how the lore reached Ching-ching in the first place is a complex question. As we’ll see, there is some reason to believe that detailed information concerning the temple tradition may have survived in heretical Christian circles in the Middle East, but the Nestorian church also established an enduring presence in India, which could have absorbed the necessary lore there. The fact that Ching-ching apparently felt no qualms of conscience about helping a missionary from a different religion translate his scriptures into Chinese suggests that he was a man of unusually tolerant opinions, a point that broadens the possible range of sources even further.

Whatever Ching-ching may have bequeathed to Saicho and Kukai found little place in the esoteric Buddhist sects these latter two founded. Like the rest of Japanese Buddhism, the esoteric sects adopted the standard Chinese approach to Buddhist architecture for their own use and adapted it to Japanese conditions.69 There were good reasons why this should have happened. In Japan, broadly speaking, Shinto is the religion of life and nature, and Buddhism is the religion of the afterlife and the supernatural. A Japanese person’s religious life begins in a Shinto shrine, where he or she will be presented to the kami not long after birth, and ends in a Buddhist temple, where the funeral and the offerings to the ancestral spirits take place. Thus it makes sense in terms of the Japanese religious imagination that the temple tradition, with its links to life and fertility, was assigned to Shinto early on, and Buddhist temples and monasteries followed different design principles, acquired different legends—and had different practical effects.

The Rebuilding of the Temple

Christianity, finally, came into being in a society crammed with temples, and Herod’s Temple in Jerusalem, in particular, was a massive presence in the first days of the newborn faith. Some of the major events in the life of Christ as depicted in the four officially approved gospels took place in or near the Temple. Among them are the appearance of the archangel Gabriel to Zechariah announcing the birth of John the Baptist,70 the first recognition of Jesus as the Messiah,71 Jesus teaching the elders at the age of twelve,72 the flogging of the moneychangers,73 the prophecy on the Mount of Olives overlooking the temple,74 and the rending of the veil of the Holy of Holies at the moment of Christ’s death.75

As the new religion began to define itself in contrast to Judaism and the Pagan faiths of the Hellenistic world, however, many early Christian writers deliberately distanced themselves not just from the temple in Jerusalem but from temples in general. Much early Christian writing draws a hard contrast between the physical temple of Jewish worship and an assortment of metaphorical temples “not made with hands” that were to be central to Christian faith. Thus the promised New Jerusalem of the last two chapters of the book of Revelation, unlike the material city familiar to the earliest Christians, has no temple in it at all, “for its temple is the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb.”76 Along the same lines in the third century, the church father Minucius Felix could state categorically, “We have no temples; we have no altars.”77

These distinctions were not simply a matter of language. Christians in the early centuries of their faith’s history refused to engage in any practice too closely reminiscent of the surrounding temple cults. Their refusal to practice animal sacrifice or to eat meat offered to Pagan deities is well attested in Christian and Pagan sources. Less widely known, though just as significant, was their refusal to use incense in a religious context, not only in Pagan ceremonies but in their own sacraments as well.78

All this changed dramatically when Constantine’s Edict of Milan abolished the legal proscription of Christianity and brought the new faith under imperial patronage and control. In place of the remodeled houses and catacombs Christians used for worship during the era of persecution, substantial church buildings as large as Pagan temples rose in urban centers around the empire. The new churches didn’t use the temple architecture the Roman world inherited from the Greeks, partly because that architecture was too deeply intertwined with Pagan tradition to be acceptable to Christians and partly because the differences between Christian and Pagan ritual required a different kind of building—one that could accommodate large congregations inside to witness the ceremony of the Mass and the other sacraments.

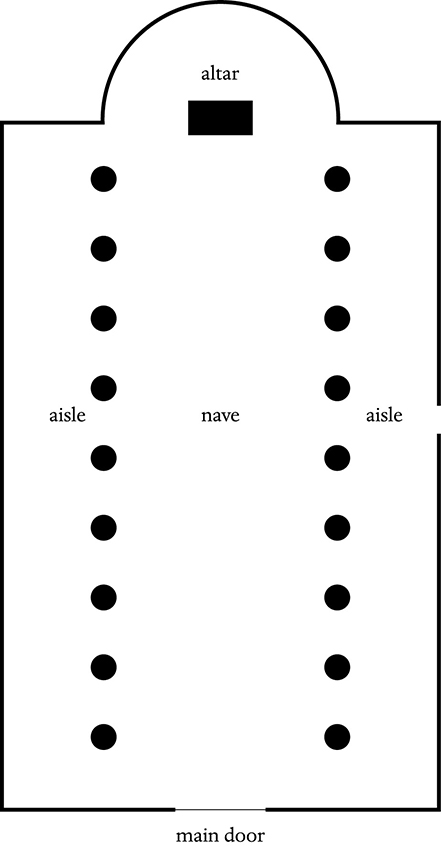

The design that became standard was based on the basilica, the standard Roman design for government facilities meant for public use. In its secular form, the basilica was a long rectangle divided by a double row of pillars into a wide central space and two aisles extending up the sides. The doors were at one end; at the other end, often set in a semicircular apse, was a dais with a throne for the presiding official. Place an altar on the dais and decorate the walls with mosaics on Christian themes rather than secular ones, and you have the standard design of a Christian church during the last centuries of the Roman world; see illustration on page 78.

Inevitably, concepts and symbols from the older temple traditions began to slip back into Christian practice the moment the new churches began to rise. Eusebius, Constantine’s Christian adviser, launched this process by using biblical texts about the building of Solomon’s Temple to provide a symbolic frame for church construction. His speech at the dedication of the church at Tyre compares the bishop of that town to Bezaleel, Solomon, and Zerubbabel, the builders of the Tabernacle, First Temple, and Second Temple respectively.79

Rhetoric along those lines had an inevitable impact on the more practical dimensions of church design. It’s surely not an accident, for example, that the baptismal font in Christian churches from the time of Eusebius to the Reformation was almost always placed in roughly the same location relative to the main body of the church that the brazen sea had in relation to the Holy Place of Solomon’s temple—either just inside the entrance of the church and over to one side, or in a separate baptistery building just outside the church proper—or that the font itself routinely resembled nothing so much as a small-scale replica of the brazen sea itself.

Other examples of borrowing from the older temple tradition are less easily explained from biblical sources. As Christian churches spread across Europe, for example, it became standard practice to surround them with a churchyard, a sacred area into which certain classes of people were not supposed to enter until cleansed with the appropriate ritual. Women who had recently given birth, for example, were not supposed to return to regular attendance until they had been “churched,” that is, blessed by means of a traditional service. Every member of the congregation was expected to purify himself or herself with holy water before entering the church, and incense came to play an important role in the services. All these were straightforward borrowings from Greek Pagan practice.

Borrowings of the same kind took place at a far more profound level as well. In the centuries following the Edict of Milan, a great many Greek and Roman intellectuals who became Christian brought with them the same Neoplatonist philosophy that Sallust and his peers had applied to the Pagan Mysteries, and these intellectuals came to conceptualize Christianity as a mystery tradition along the same lines as the Mysteries of Eleusis or Cybele. Some of the products of this fusion ended up being adopted enthusiastically by the leadership of the new faith—for example, the writings of a sixth-century Christian Neoplatonist who wrote under the pseudonym of Dionysius the Areopagite became central to Christian theology for most of a millennium after his time, and still have that status in the Eastern Orthodox churches—while others strayed outside the boundaries of orthodoxy in various directions.

Quite a bit of material from the old Mysteries seem to have come across into Christian practice through these channels. David Fideler’s intriguing study Jesus Christ Sun of God has shown that the rich Greek tradition of cosmology and number association with the half-legendary figure of Pythagoras found a home very early on in Christianity and kickstarted a tradition of numerical and geometrical symbolism in the Christian church that remained a living source of inspiration for well over a millennium thereafter.80 It may well have been through these connections that the temple tradition first found its way into Christian practice—though, as we’ll see, it received at least one, and probably two, substantial inputs from other sources later on.

The Temple Tradition in Christianity

One of the things that makes it difficult for many modern people to notice the continuities between Christianity and the older Pagan faiths is that the Christianity practiced in most of the world today has little in common with ancient and medieval Christianity but the name. Ask a devout Christian in today’s America about the basic elements of his faith, for example, and odds are you’ll be told that Christianity is about having a personal relationship with Jesus Christ, and its central practices are prayer, Bible study, and weekly attendance at church services that include prayer, congregational singing, and listening to a sermon. All these are standard elements of modern Christianity, but they came in with the Reformation, when much of what had previously been standard Christian belief and practice was discarded.

If you could ask a devout Christian in early medieval Europe about the basic elements of his faith, by contrast, you’d get a completely different answer. At that time, for most people the thought of having a personal relationship with Jesus Christ was rather like an ordinary American citizen expecting to have a personal relationship with the president; most people’s personal spiritual relationship was with one of the saints, who was their link with the Church as the mystical Body of Christ. Bible study was an esoteric branch of scholarship mostly of interest to theologians, and while prayer had an important role in daily spiritual life, the heart of religion was the sacramental rituals practiced at every church in Western Christendom.

Those rituals had a dimension that’s not widely known these days outside of the more traditional Christian denominations. To this day in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches alike, Mass can only be celebrated properly if the altar contains part of the corpse of a dead saint. In earlier times before the Reformation, the relics of the dead were even more central to Christian faith and practice. All those who could afford to do so had at least a minor relic of some local saint in their homes as a focus for private devotion; churches vied with each other for possession of the most extensive collection of relics of the holy dead, and the idea of being buried somewhere other than a churchyard or, better still, in the church itself, was all but unthinkable—so dire a fate was reserved solely for the worst of unrepentant sinners.

In those days the sacraments of the church and the cult of the dead formed the center of religious life in ways that would seem profoundly alien to modern believers. If you were an ordinary parishioner in the Middle Ages, you might well not attend Mass more than once a year, and then only after the austerities of Lent had purified you to the point that you could risk contact with the perilously holy divine presence in the communion wafer. It was the grace conferred by your baptism, the powerful assistance of your patron saint, the blessings conferred by devotion to relics and the sacraments, your own avoidance or repentance of mortal sin, and the final help of the last rites that would help you escape the traps laid out for you by God’s sworn enemy, the fallen angel Sathanas, and make your way to safety in heaven.

The church you attended—whether it was a great urban cathedral, the abbey church connected to a monastery, or a humble parish church—was the spiritual powerhouse behind the whole system, the place where a priest ordained by the heirs of Christ’s apostles spoke the words and performed the rites that renewed the descent of Christ into the fallen word of matter. When you went to church, if you lived in the countryside, you generally got to your destination along a set of straight tracks that radiated out across the parish and were used only for going to church for worship or taking the dead there for last rites and burial. At the end of the track, you passed through a gate in the low wall surrounding the church, crossed a churchyard full of tombstones and ancient trees, and came to the door set aside for ordinary use, which was usually a side door—very rarely the main doors at the far end of the church; see illustration on page 82.

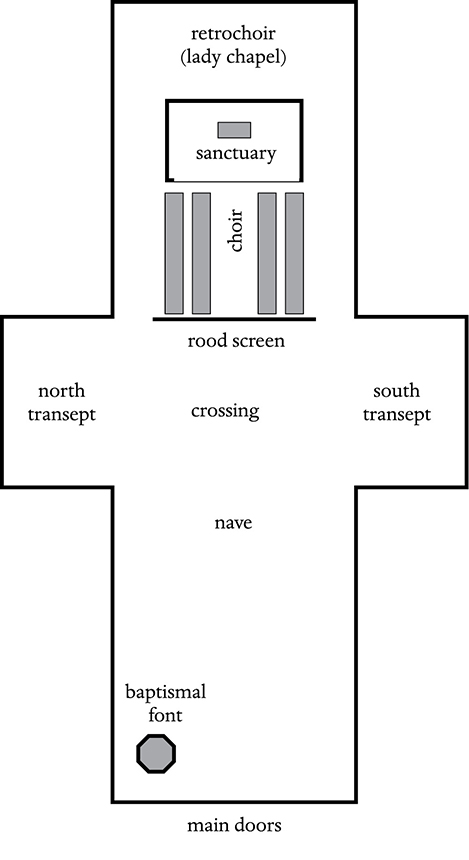

Inside, if you were going to attend a High Mass, the most elaborate form of the Church’s central sacrament, your place was usually in the nave, the main body of the church to the west of the choir and sanctuary. (The word nave comes from the Latin word for “ship,” the same word that yields English words such as “naval” and “navigation;” an ancient and complex symbolism lies behind the term.) You would sit or stand there, depending on your social class, and look toward the rood screen, so called because it carried a large image of Christ on the Cross; rood was the Middle English word for “cross.” The rood screen was a barrier of wood or stone that sheltered you from the sacred Mysteries being enacted beyond it in the sanctuary. People in the Middle Ages thus spoke of hearing Mass rather than attending it.

If you weren’t there to hear High Mass, where you went depended on what your purpose was. If a child was to be baptized, that was performed at the font in the west end of the church. If a wedding was to be performed, that took place at the porch by the entrance most often used—the matrimonial Mass now performed by Catholic priests came in after the Reformation. Other sacraments often didn’t take place at the church at all—priests usually performed the last rites in the homes of dying parishioners, and confession and absolution could be accomplished in any relatively private place.

If you were there to pray to your patron saint, on the other hand, you would go to the chapel set aside for that worthy, which might be in one of the two transepts or in the aisles to either side of the nave and the choir. If your patron was the Virgin Mary, on the other hand, her chapel—the Lady Chapel, as it was called—was most often in the retrochoir, the eastern end of the church beyond the sanctuary. Low Masses would be celebrated in the chapels from time to time, especially for the souls of the dead and other worthy causes. Curiously, it was not in any way inappropriate for the ordinary faithful to watch the Mass when it was performed in a chapel. Only the High Mass performed in the sanctuary of the church had to be hidden by the protective rood screen from all but ordained clergy.

Those of my readers who have been paying attention will already have noticed the close parallels between these arrangements and the temple traditions already surveyed in this book. Like the Temple of Solomon, the core ritual space of churches built between the early Dark Ages and the Reformation was divided into an area for worshippers—indoors rather than outdoors, due to the colder and wetter climate of Europe—a place for ordinary clergy, and an innermost space for the presiding priest. Like the temples of ancient Egypt, the inmost sanctuary was surrounded by smaller chapels dedicated to other holy beings, where ceremonies of secondary importance took place. Like the temples of ancient Greece or the shrines of contemporary Shinto, the entire structure was surrounded by a sacred enclosure and a galaxy of ceremonial taboos that are hard to explain in terms of Christian theology but easy to understand in terms of the surviving traditions far more ancient than Christianity.

And the role of agricultural fertility in the medieval European church? To understand that, it’s necessary to look at a different body of evidence—the collection of strange and luminous legends that seem to blend Pagan and Christian motifs and center around that enigmatic object, the Holy Grail.

64 Patai 1990.

65 Boyce 1979, 6, 46, and 60.

66 Ibid., 61–62.

67 Hamblin and Seely 2007, 103.

68 Jenkins 2008, 15–16.

69 Kidder 1964.

70 Luke 1:5–25.

71 Ibid., 2:22–38.

72 Ibid., 2:41–52.

73 Matthew 21:12, Mark 11:15, and Luke 19:45–46.

74 Matthew 24 and Mark 13.

75 Luke 23:45.

76 Revelations 21:22.

77 Jones et al. 1992, 529.

78 Ibid., 486.

79 Lundquist 2008, 156–7.

80 von Simson 1962, 21–50.