The renaissance in beer making that started several decades ago had its roots in the brewing centers of the world, a factor noted by the new generation of craftsmen. Flavors and styles were adapted by this group of artisan brewers, often designed to please themselves and their colleagues. No longer would the mass-marketed varieties be adequate; it was time for a change. Beer makers opted to create their own take on how beer should taste and trusted that the public would approve.

These artisan brewers analyzed what was in the market, frequently using non-American beers as their guide. In my talks with brewers, especially those in the midst of building a new beverage, it would not be unusual to see bottles of various beers being sampled and dissected. “What do I like about this?” “How can I accomplish what I want, yet remain true to the style?” were questions asked.

Small test batches were produced and people, often from the general public, provided feedback, much of which was employed in the final recipe. Ultimately, however, the brewer decided for himself the specifics and then produced his beer.

Now, well into the twenty-first century, this new group of artisans has taken the reins. They started as homebrewers, honing their skills on a limited basis to a small but appreciative audience. There are no rules, ingredients vary, and, in some cases, brewers do not replicate the same beer twice. Imagine drinking a Budweiser or Coors that didn’t always taste the same! That’s part of the beauty of beer today.

I had my first taste of beer before the age of two. That got your attention, didn’t it? I’m not petitioning for a guest spot on Intervention, nor am I suggesting that I’ve ever had an issue with alcohol abuse in my family. I can recall my mother having a glass of beer and giving me a sip—much to the amusement to the rest of my family—because I liked the feel of “toam” (that’s “foam” to you). I don’t think she really liked the stuff that much, but everyone seemed to enjoy my performance whenever a bottle was opened.

Even as a young boy and well shy of legal drinking age, I was able to have a beer at home, under the supervision of my parents. This made me the envy of all the guys in my neighborhood. Friends would tell me how cool my dad was because I was allowed to drink at home.

In reality they had no idea of my parents’ logic. My mother and father felt that, under proper supervision, a slight intake of beer would instill respect for the beverage when a child was maturing. Think of it. Tell a child not to do something and what frequently is the outcome? That kid wants to do what is forbidden. Knock on wood, but overconsumption never was a concern for me. I guess you could call it “love at first sip,” but, as you now understand, my love of beer has existed just about as long as I’ve been alive. And now we are in an era when the choices are broad with flavors to suit all tastes. It is the perfect time to enjoy the most social of all adult beverages, beer.

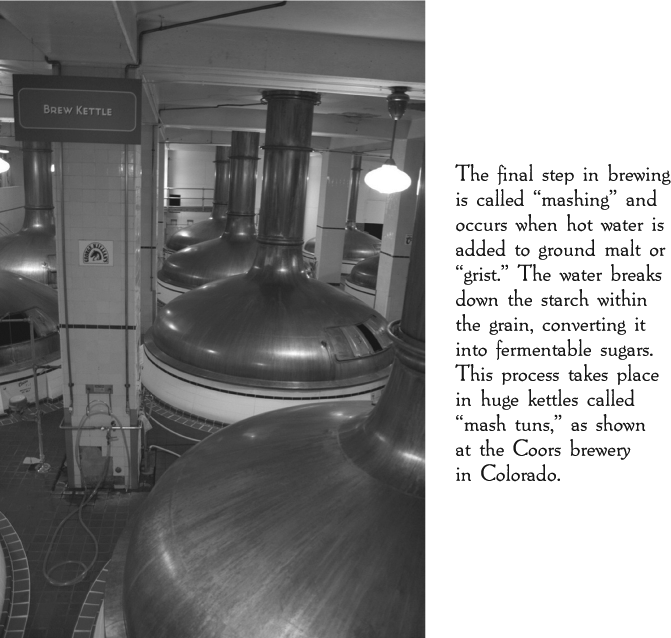

In its most basic form, beer is made from water, yeast, an herb or spice for flavor, and a malted grain. Although barley normally is that grain, rice, corn, wheat, and other items can also be used.

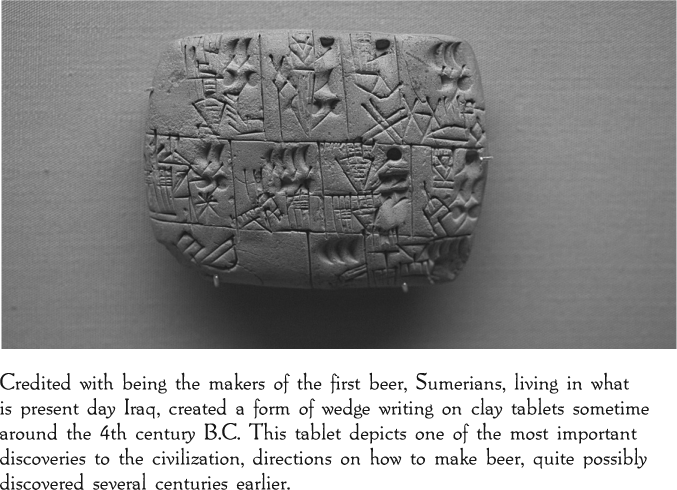

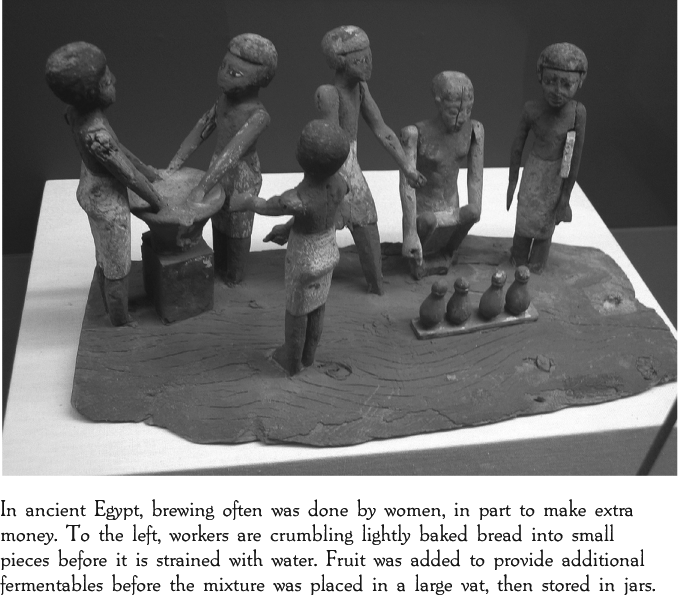

Evidence exists that barley, a substance that produces good beer but not-so-good bread, was grown six thousand years ago in Mesopotamia. Other cultures, such as that of the Sumerians, have left artifacts that affirm the production of beer. In some societies, beer served as legal tender. The people who built the Egyptian pyramids were given the beverage as payment, known as kash. It would be safe to say that the drink was accepted universally throughout the recorded history of humankind.

For hundreds of years, beer was perceived as a nutritious concoction, at least in part because the presence of alcohol made it a safer beverage choice than water.

As time progressed, the science of brewing evolved into a deep-rooted native trade, where the drink was made for local consumption. Because transportation consisted of horse-drawn carts traversing bumpy dirt roads, it made little sense to worry about sending beer over long distances. That thought, however, came to an end during the era of exploration to the New World.

Although a maize beer was created by Mexicans, brewing first took place in what would become the colonies in the late 1500s, years before the first settlement at Jamestown. In September 1620, the Pilgrims set sail on the ship Mayflower from England. The 102 people on board (only 35 of whom actually sought religious freedom) simply wanted to leave England for a new life in America. The two-thousand-mile voyage took over two months to complete.

Aboard the ship were items such as bread, fruits, dried meats, cheese—and beer. Unusual, you say? Including beer on sea crossings was common practice in the years prior to refrigeration, as fresh water would go bad quickly. (Remember, this was before chlorine and filtered water.) With its alcohol content, beer remained potable longer than water. Additionally, there are records indicating that the Pilgrims landed on the shores of Massachusetts in part because of a lack of beer.

In Saints and Strangers, author George F. Willison refers to John Alden as “tall, blond and very powerful in physique … a cooper by trade, he was now carefully tending the Pilgrims’ precious barrels of beer.”

A journal entry from 1622 declared that the Pilgrims actively looked for a place to set up a permanent landing, “our victuals being much spent, especially our beer.”

Had there been more beer on the ship, might they have landed on what now is New York? As for the Puritans who set sail for Massachusetts Bay a decade later, Willison wrote that their “good ship Arbella carried 10,000 gallons of wine, fourteen tons of fresh water and forty-two tons of beer.”

Throughout the seventeenth century, those people who chose to travel to the colonies of Maryland and Virginia faced similar risks: pirates, warships, storms, sickness, and disease. Add to that the sameness of being at sea with no change of surroundings. Conditions were cramped with little headroom, causing people to travel with supplies and much of the ship’s cargo. Ventilation was poor. Depending on one’s social status, time spent on deck was limited and occurred only when there would be no interference with the sailors who labored on the ship. During times of inclement weather, air hatches were sealed to prevent water from entering. Diseases such as dysentery or typhoid spread quickly.

Food that was brought on board usually was eaten cold, although some of it could be cooked on the ship’s hearth, depending upon the size of the vessel. In any event, the same foods were eaten every day. Biscuits, known as hardtack, were baked until rock-hard so they might last as long as possible. Before they were eaten, they would be soaked in beer to try to soften them. Why beer and not water? As I mentioned earlier, beer remained safe to drink, whereas water turned bad. It was common practice to use one’s teeth to strain water in an effort to remove the algae and bugs that tended to fill the cask after a week.

Make no mistake about it, although beer remained drinkable for much longer than water, it did not have an endless shelf life. The British navy had to cope with long journeys, especially when traveling to warm regions, resulting in flat, spoiled beer. Keep in mind that these primitive brews were unfiltered, suggesting that they were cloudy in appearance. That murkiness came from the presence of yeast, meaning that not having beer usually meant not having the B vitamins that the drink supplied. In addition, the beer was relatively weak, providing just enough alcohol to keep the fresh water from turning undrinkable.

By the mid-1700s, another beverage became popular with sailors: grog. Because colonization had expanded and the men aboard the ships were being sent on longer expeditions, some of which were to balmy climates, grog became the drink of choice. Rum was issued to sailors, but many instances of drunkenness occurred, adversely affecting the operation of the ship. Up to one-quarter of a pint of rum was given twice a day to each person. In time, Admiral Edward Vernon ordered it to be diluted at the rate of one part rum to three parts water. Vernon had the nickname “Old Grogram” because of the grogram coat he wore, and his sailors called the diluted rum grog after the admiral. The term groggy originated at this time, an indication of a person who was feeling the effects of drinking a bit too much. The rationing of rum continued in the Royal Navy until 1969.

Sailors stationed in the English Channel maintained their love of beer and were issued a gallon of it daily, per person. The same practice applied to all men stationed in cool climates. The problem of keeping the drink fresh for those long trips into the tropics had to be addressed.

Before the end of the century, the government decided to get involved. A number of ideas were put forth and considered. Finally, a suggestion was made that brewers should boil away most of the wort (pronounced wert, this is the liquid prior to fermentation). Then sailors could add water at sea, providing a fresher beverage. Even though this procedure worked well in cool waters, the obstacle relating to warm territories was not overcome. As British troops moved into India, something had to be done, and soon.

To preserve as much freshness as possible, ale was placed in the lower part of the ship’s hull, the coolest part of the vessel. Yet the temperature varied greatly. Documents from this time period confirm a range from the low fifties to the mid-eighties, particularly when the ships entered the equatorial regions and also as they approached India. Take a four- or five-month crossing and couple it with temperature extremes and the constant swaying of the boat and you have the ingredients for severely damaging the quality of any beer. Yet brewers continued to make beer for export.

Porter, a dark roasty style of beer that was extremely popular in London, typically was the beer sent to India. Regrettably, it arrived tasting stale and sour. Also, the dark ales plainly were not as satisfying to the colonists now living in the warmth of their new country.

The solution came from a brewer living in London. Until this time, most brewers were trying to alter their methods, in an attempt to turn out a more stable beer. George Hodgson, however, created his India ale, a derivation of his pale ale.

Hodgson’s ales were among the first beers that were not brown or black. What separated India ales from all others was the increased alcohol content, a primary weapon against spoilage. Brewers also recognized the preservative qualities that hops offered. Consequently, Hodgson added an additional dose of hops (and more sugar) to keep the yeast functioning during the lengthy voyage. The end result was a bitter, bubbly pale ale that successfully survived the long trip. Hodgson became a folk hero. Within twenty-five years, beer shipments to India increased fivefold.

By 1830, Hodgson controlled the Indian market, although some unethical business methods were employed. Upon hearing that another brewer was preparing pale ale for export, Hodgson flooded the market with his product, effectively lowering the price and removing competition. Then, in following years, he reduced deliveries, thus recovering lost profits from the past.

Success breeds copiers, and there was no shortage of them throughout England. The best came from an area known as Burton-on-Trent, now considered the brewing hub of the country. The secret was in the water, possibly the most overlooked component in the construction of beer. Burton water is high in sulfates, allowing the brewer to vary the amount of hops used. The net result was a strong, flavorful ale that tasted better and had a longer shelf life than that of Hodgson, ultimately leading to his demise.

India pale ale or IPA remained an export-only drink until a ship heading for India was demolished. Its cargo was sold, and Britons were exposed to this beer’s existence. It became enormously popular locally and soon spread throughout much of Western Europe. These were powerful beers indeed, approaching 10 percent alcohol by volume. Before the end of the nineteenth century, all that changed and India pale ales became remarkably weaker.

The British government moved from a structure that taxed the raw materials used, to one that was reliant upon the alcohol content of the wort. Hence, watery beers now were produced. As the Industrial Revolution came to be, including the introduction of refrigeration, IPAs fell out of favor, replaced in the colonial trade as the Germans gained recognition with lager beer.

The practice of equating beer with seafaring has been revived by the Global Beer Network, importers of Piraat, a Belgian-made 10.5 percent alcohol-by-volume India pale ale, brewed in the tradition of the type of beer that probably was found on many seventeenth- and eighteenth-century ships.

Mechanical refrigeration was the single most important innovation that changed the brewing industry. It allowed beer to be moved worldwide. The invention of the microscope meant that yeast action could be studied and improved. As the drinkability of the beverage increased, so did the distance that beer could be successfully shipped. Within a few generations, improvements in transportation changed people from hesitant to enthusiastic travelers.

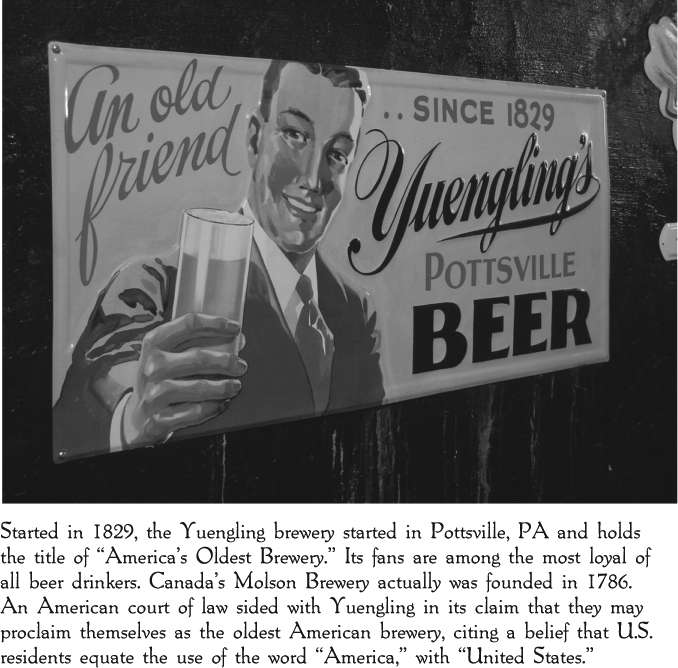

Beer has been popular in the United States since the country’s inception. There were more breweries in the late nineteenth century than exist today, but there are different concerns. Obviously, back then access to a variety of beers was limited because transportation simply didn’t allow for extensive distribution. Consequently, I’ll limit any further discussion regarding beer history to the period from the mid-1970s forward.

Certain key events that took place in that decade still resound today. The year 1976 is considered a landmark in American beer history, as it was in October of that year that the first modern microbrewery, New Albion Brewing Co. of Sonoma, California, was incorporated. Keep in mind that the working definition of a microbrewery is a company producing up to fifteen thousand barrels (17,600 hectoliters) of beer annually. Today the word microbrewery has evolved into craft brewery, an independently owned business turning out up to two million barrels of beer a year. Near the end of the 1970s, there were fewer than fifty breweries in the entire country. Contrast that with a hundred years prior, when close to three thousand breweries existed nationwide.

Although New Albion lasted only six years, the wheels were in motion for an increased interest in full-flavored beers, as opposed to the mass-marketed, cookie-cutter beverages that had been the norm.

Also in the late 1970s, two other elements provided direction for this burgeoning industry. A British writer, Michael Jackson, achieved acclaim for his 1977 book, The World Guide to Beer, legitimizing the trade and alerting the masses to the fact that the American beer scene was about to change. In October 1978, President Jimmy Carter signed a decree that legalized homebrewing at the federal level. It was this piece of legislation that was the driving force behind authorization to sanction more areas to permit microbreweries. Less than a decade later, a number of western states had their own micros, including the still-thriving Sierra Nevada Brewing Co. of Chico, California. By the way, I would be remiss not to mention the contribution of Fritz Maytag of appliance fame, who took ownership of a failing San Francisco, California, brewery, the Anchor Brewing Co., and transformed it into a classic example of an industry leader. Anchor remains one of the most respected companies in the business.

In the 1980s, a splinter from the micro, the “brewpub,” came into being. What distinguished it from a brewery was the fact that food was served in the place where the beer was made. Although the handcrafted beer remained the primary attraction for those who frequented the brewpub, as time progressed emphasis was given to food preparation. Today any good brewpub will feature an extensive array of beers and a bill of fare that complements the house brews. Some brewpubs have received recognition for excellence from prestigious culinary publications.

The trend toward more flavorful drinks—now known by a number of names, including craft beer and boutique beer—expanded geographically when the Manhattan Brewing Co. became the first brewpub to open in the East, in New York City. One of the brewers there was Garrett Oliver, who later achieved fame as the brewmaster of the Brooklyn Brewery. No one furthered the developing relationship between beer and food more than Oliver, by way of numerous speaking appearances centered on books he authored, especially The Brewmaster’s Table, an authoritative expression of beer styles and fine cuisine.

Another pioneer in the business was Jim Koch (pronounced cook), who in the 1980s decided to carry on his family’s tradition by starting the Boston Beer Company, maker of the popular Samuel Adams line of products. With its flagship Samuel Adams Boston Lager, along with other styles emerging, the company expanded from a few thousand barrels a year to over a million.

Make no mistake about it, despite the enormous surge in the popularity of handcrafted brews, sales of the beverages made by the giants of the trade continued to flourish. Well into the 1990s, the “Big Three”—Anheuser-Busch, Coors, and Miller Brewing— produced three of every four domestic beers. In fact, Anheuser-Busch had surpassed the billion mark in cases produced worldwide. Clever advertising promotions perpetuated the image of the “typical” American beer drinker as a male blue-collar worker and a sports devotee. By the end of the century, however, the perception of that drinker had changed somewhat to include men and women, cultural differences, and the like. This shift in attitudes was fueled by an array of books and periodicals on the subject of beer. In short, the consumer had become more educated. Fifteen hundred breweries operated, and all but a couple of dozen were specialty breweries, turning out new flavors and styles. Remember those 1979 figures? Of forty-four breweries, only two could be considered as specialties.

If you think the popularity of these “new” beers, now called boutique or craft, sounded the death knell for the large breweries, nothing could be farther from the truth. The Brookston Beer Bulletin published a listing of the top fifty breweries based on 2009 sales. To no one’s surprise, the top three were Anheuser-Busch, MillerCoors, and Pabst. Clearly, they are doing something very right. To weigh the immense size of A-B, for example, just two of their brands, Bud Light (the best seller in the United States) and Budweiser, are responsible for annually shipping over seventy million barrels of beer worldwide. Contrast that with a company such as O’Fallon Brewery in Missouri. Keeping in mind that most breweries don’t distribute outside their immediate area, O’Fallon sends its beers to about a dozen states in its part of the country. Yet the total number of barrels brewed is approximately four thousand annually, the equivalent of about fifty-four thousand cases. And that reflects a 37 percent increase from 2008.

Too often we hear it said that beer no longer is a “hip” drink. I recall once walking into a brewpub where eight female servers who had finished their shifts were seated at the bar, enjoying a drink. Seven of them had a colorful martini—well, at least the twenty-first-century version of a martini. Only one was drinking beer. I asked them why so few were drinking their company’s beverage and the response was that they really didn’t consider beer to be in vogue. I then asked what made it so outdated, in their estimation. Answers didn’t waver among the women, with most saying that it wasn’t colorful enough or was the drink favored by their fathers and they wanted their own style.

Are those valid claims? Although the sample size is small, I’ve seen this phenomenon repeated elsewhere. So then, if beer isn’t dead, is it wounded?

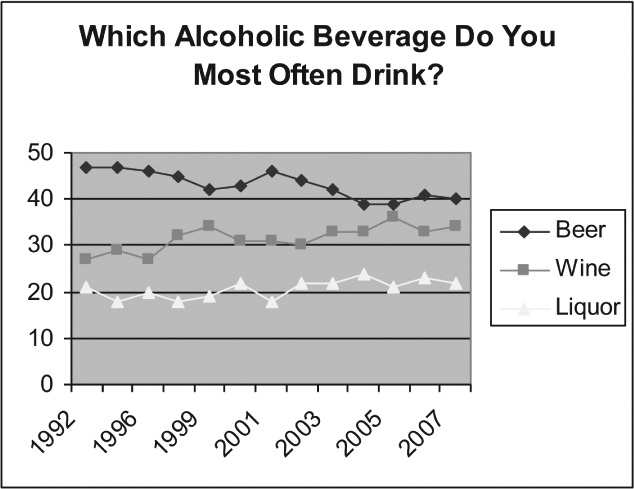

Many of us recall a 2005 Gallup Poll suggesting that wine had tied beer as the adult beverage of choice. I recall many members of the press, as well as non-beer-drinkers, jumped on the story in their quest to back up claims that the popularity of beer was waning. Now, I’ll admit that the numbers do show a narrowing of the gap among wine, spirits, and beer. The question is why? I think the gals I spoke with in the brewpub were on target. The wine and spirits people have done a remarkable job of promoting their preferred beverages to prominence.

Look at advertisements for these products. They usually reflect some degree of elegance. There’s a fancy party or hip club scene attended by beautiful people clad in the latest designer clothing. They are the “beautiful people.”

I have to applaud what is going on in the sake world, too. By tradition, the drink is presented in a small wooden box cup called masu. I’ve seen ceramics used, but for the most part you’ll see sake served in glass stemware, much the way you’d order wine. Which looks more elegant and more upscale “American”? Yet sake, mistakenly referred to as “rice wine,” actually is similar to beer in development. Multiple fermentations takes place; starch is converted to sugar, then the sugar changes to alcohol via the introduction of yeast. Mr. Restaurant Owner, try offering this to your customers in a wooden box and see the looks you’ll get. Serve it in a tulip glass and realize how easy it is to get seven dollars.

Compare that with the beer ads that still are common today. You’ll see guys sitting around the television on a Sunday afternoon, eating pretzels and chips and pounding down the longnecks by the six-pack. One ad speaks elegance and exclusivity, the other screams commonality. In dealing with a generation of people brought up on upscale merchandise and lifestyle, is it any wonder that they are favoring colorful twenty-first-century Kool-Aid pop “martinis”?

The beer industry should not be held innocent. The gap between the mega- and microbrewers has been just what the rest of the beverage world needed.

What has happened in the last couple of years to swing the numbers back in favor of beer, at least according to the folks at Gallup? It’s not in the number of people who call themselves drinkers. In 1945, the percentage of Americans who said they use alcohol was 67 percent. In mid-2007, that number was 64 percent. Gallup did find that young male drinkers prefer beer, but women and older people in general favor wine. The survey indicated that people are drinking more, with the average drinker consuming 4.8 drinks per week as compared with under 4 as recently as 2001.

Over the last few years, there has been an influx of more unusual beer flavors, incorporating atypical ingredients. Take a look at Dogfish Head Brewery as a prime example. At any one time, you’ll find beers such as Festina Pêche, a Berliner weisse made with peaches; Chateau Jiahu, an ancient Chinese re-creation using rice flakes, wildflower honey, Muscat grapes, hawthorn fruit, chrysanthemum flowers, and sake yeast; Fort, a raspberry-infused fruit beer that tops out at 18 percent alcohol by volume (ABV); and Midas Touch Golden Elixir, a hybrid based on the funerary feast of King Midas: elements of barley (beer), Muscat grapes (wine), and honey (mead). To top things off, saffron, one of the most expensive spices in the world, is added to the mix. You don’t think the introduction of those beers didn’t excite beer drinkers? As esoteric as Dogfish Head is, what they are doing is being replicated at small breweries throughout the country. I once asked a brewer why he was experimenting with bizarre ingredients in his recipes. He said, “I’m small. I’ll always remain small. I can afford to take chances and, quite frankly, my customers like it.”

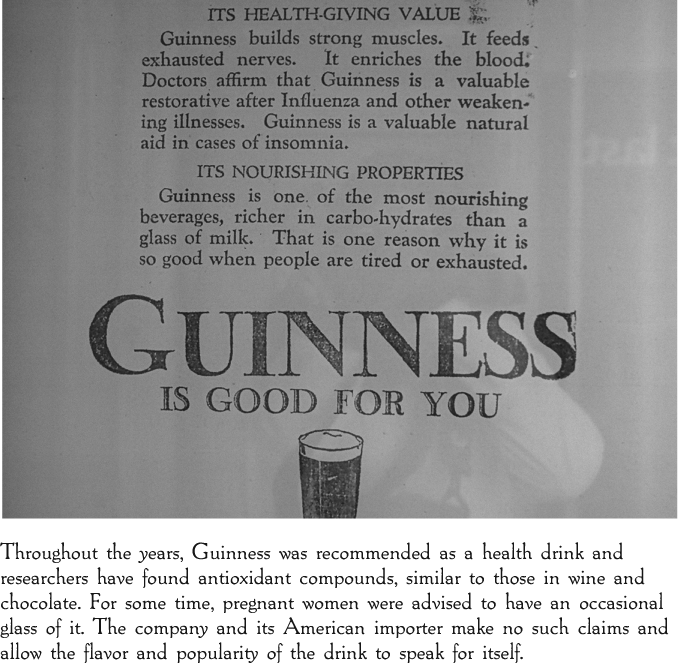

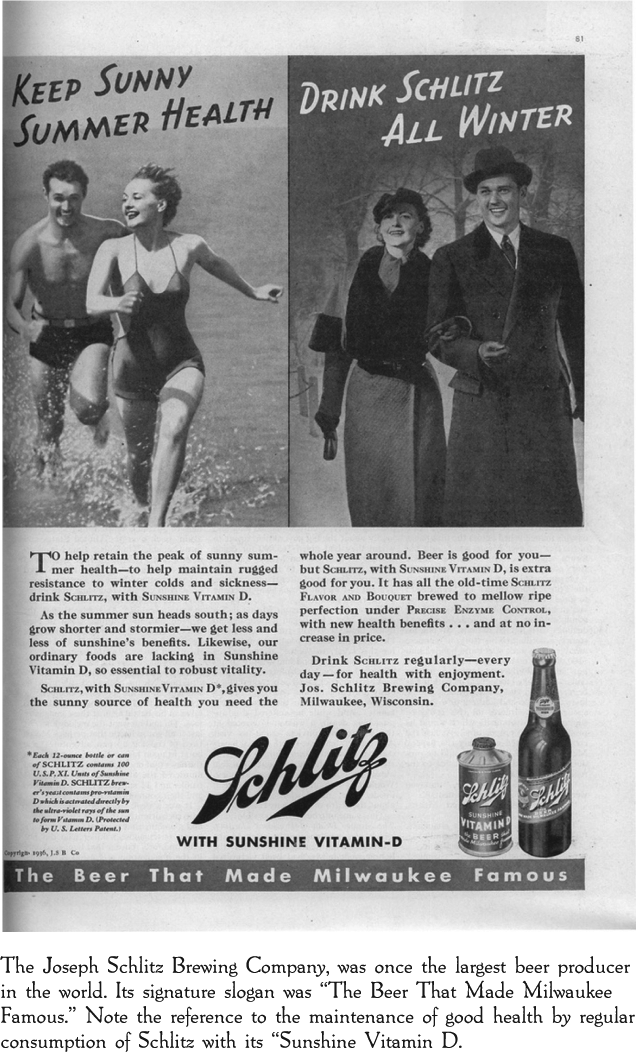

Perhaps not so coincidentally, the upsurge in regular drinking has coincided with medical reports suggesting that not only is moderate drinking harmless, but it may also have health benefits. Initially, red wine consumption was linked with heart protection, but more recently that has extended to beer.

According to the Brewers Association, moderate beer consumption (no more than two drinks a day for men, one for women) may be able to:

Lastly, beer contains no fat or cholesterol. The calories come principally from the alcohol.

As with most things in this world, the key is moderation. If taking a one-hundred-milligram tablet of vitamin E is good, would ingesting fifty times that amount be fifty times better? Because vitamin E acts as an anticoagulant that could lead to bleeding, drastically increasing the dosage is foolish. Likewise, having a couple of bottles of beer a day may have the previously mentioned positives, but multiplying one’s intake radically will cause health problems and probably won’t do much to guarantee the longevity of your job or marriage.