Throughout my travels, I meet a lot of people who want to talk about beer. Invariably, questions are asked, many of which are repeated. First and foremost, people want to know if I need an assistant. At this point I don’t; fortunately there is no shortage of applicants waiting in the wings.

Second, there are those who want to know how I got started in this business. How people end up doing the things they do can be a complex journey. It’s the rare person who decides at an early age what his calling in life might be. I doubt if too many kids decide to go into the beverage industry, although I do suppose some dabble in it in certain ways (wink).

I work as a full-time computer teacher. As such, my schedule allows me to have a couple of months away from the classroom each summer. Of course, that’s time without a paycheck. Many in my profession hold second jobs, and some are preparing themselves for life after education. I tried different things back in the 1980s. I created personalized children’s books for a brief while, investing plenty of money but seeing little return. I served as a computer consultant for a couple of years and worked on a delivery truck for one summer. Nothing gave me satisfaction. Then, for Christmas of 1991, the father of one of my students gave me a book about beer, written by Michael “The Beer Hunter” Jackson. I should mention that the parent and I had known each other since we were teenagers, thus he knew of my love for the beverage. Upon browsing through the book, my first words were, “You mean you can have a career writing about beer?” If it were only so easy.

I approached the editor of my local newspaper and asked if he might be interested in running a column that reviewed an upcoming beer festival in Pennsylvania. I proposed giving him a thousand words and a few pictures and ended my offer by saying that, if he liked it, he could use it for free. The piece ran and I was offered a monthly column with the paper at the rate of twenty-five dollars per article.

From there, I contacted the publisher of free monthly newspapers. You’ve probably seen them at community stores and restaurants. I did that for a couple of years, but continued to communicate with those in charge of publications that had a larger readership. Eventually, more doors opened for me. I’ve been having the time of my life since 1993, when that first column appeared in print.

When you’re attempting to learn about any subject, there are various avenues that you should explore. In today’s age, the Internet is a wonderful source for information, but there also is a good amount of false material continually being posted. Anyone can be “published” these days, with blogs being accepted as gospel. Regardless of the subject being researched, approach what you read with caution, unless you know the source. In my world, I looked to certain writers for guidance, including Mr. Jackson, Stephen Beaumont, Roger Protz, and a few others.

Most well-stocked bookstores will carry a couple of decent magazines, such as Beer Connoisseur and All About Beer. Columns tend to be insightful and well written, but beer-related news can be dated.

Then there are the beer newspapers, also called “beeriodicals” or “brewspapers.” At the front of the list are Ale Street News, Celebrator, and the Brewing News family of publications, separated by geographic region (Mid-Atlantic, Southwest, and Great Lakes, for example). These papers generally are released bimonthly. Articles and features are, for the most part, written by those people who just like good beer. Almost all write for a very limited fee, but do so because of their love of the subject. Small breweries love these journals because they offer them a way to get the word out at no cost to them. Many of these microbreweries maintain little or no advertising budget, relying upon word of mouth or small newspapers to receive needed publicity. You’ll note articles specific to parts of the country, allowing the reader the option of seeking a new beer release or possibly attend a festival in their area.

Although there is a subscription price to these newspapers, you can easily receive them for free by visiting your local brewery or brewpub. I’ve seldom seen one that didn’t stock them and make them accessible at no cost.

Given the above, nothing beats speaking with someone who is passionate about a topic. I look forward to speaking with people about beer. I’ve gone to packaged goods stores, worked my way to the beer section, and spent the better part of an hour just discussing and recommending certain beverages … whether my information was needed or not, I suppose. It’s just a character flaw.

In my years of teaching and speaking at beer tastings, I guess I’ve developed a talent at identifying when a person has a craving to know something but is a bit shy about asking. At my seminars, I can classify the attendees into certain groups. Most are curious about the “new breed” of flavors being released all the time. They think that all beer tastes pretty much the same, but know there is something going on that might be worth investigating.

There are others, normally no more than a quarter of those in audience, who have moved into the world of fine beers and want to zero in on a few brands that might be new or possibly acquire additional information about a favorite. And, of course, there typically is one person who has traveled extensively and has tasted certain beers from really small microbreweries. They also offer much to the presentation and to my personal knowledge.

As I said at the beginning of this section, many of the same questions are asked of me at the events I attend, so let’s focus on some of the most popular.

Why are dark beers so heavy?

Heaviness is subjective. I’ve heard so many people contrast two popular beers, Coors Light and Guinness, by stating that Coors goes down easy but Guinness is just too substantial to enjoy.

Much of this relates to the presentation of each beverage. Go to your favorite pub and order a pint of each. If done properly, it will take substantially longer for you to receive your Guinness than the Coors Light. It’s customarily dispensed by use of nitrogen as opposed to carbon dioxide and served at a warmer temperature, about fifty degrees or so, than is Coors. Nitrogen tends to render small, dense bubbles, the reason for the thick, creamy layer of foam that resides atop the pint. That’s not something you’re likely to find with Coors.

Much, but not all, color is generated by the type of grain(s) used. Dark grains can impart a roasted flavor, fooling the sense of taste into thinking the liquid is full and rich. We call that “mouthfeel.” So you are kind of being fooled by color, carbonation, and flavor.

Check the alcohol content of the two beers and you’ll find they are practically identical. Both come in at just a tad above 4 percent alcohol by volume (ABV).

Speaking of Guinness, how do they reproduce the tiny, compact bubbles in the can? There seems to be some sort of device inside. Draught Guinness does have something inside its container, a little plastic gadget with the creative name of “widget.” During canning, a mix of carbon dioxide and nitrogen is added. Because nitrogen is not as effervescent as “normally” carbonated beers, you’d have practically no head without the widget—the carbon dioxide would stay dissolved. The nitrogen dissolves and pressurizes the can. As the pressure increases, liquid is pushed into the little hole within the widget, squeezing the nitrogen in the gadget.

Upon popping open the can, the pressure instantly plunges (you’ll hear the whoosh). The gas inside the widget immediately forces the beer out the little hole. This release causes the dissolved carbon dioxide to form little bubbles that rise to the top of the beer, duplicating the appearance of beer discharged from a tap.

Is kegged beer better than bottled beer?

This depends upon the beer. In general, it’s safe to say that drinking beer that is as fresh as possible is best. If you go to your favorite watering hole, you may not know how long that beer has been on tap. Some beers, usually the popular varieties, have a quick turnaround time, so freshness will not be an issue. Certain craft flavors may not be as lucky. I’ve been to bars in which I’ve gone through the entire lineup of kegged beers before finally settling on a bottle instead.

Bottle-conditioned beers, those that are conditioned with a touch of added yeast, don’t work as well on tap. Time helps condition the beers, though, and they can favorably evolve over months or years.

I’m thinking about getting into homebrewing. Is it easy or difficult getting started?

Thomas Jefferson, third president of the United States and an avid homebrewer, purportedly said, “Beer, if drank in moderation, softens the temper, cheers the spirit and promotes health.”

Until 1979, if you wanted to buy beer, your choices were confined to a select few brands made by a small number of large breweries. Variety? There was plenty as long as you wanted a light-bodied, straw-colored lager style. Then, in February of that year, President Jimmy Carter signed a bill allowing anyone twenty-one years of age or older the option of brewing up to a hundred gallons of beer a year within his own home, as long as the beer is for personal consumption.

Invariably, the question of constitutionality is asked. Although beer now could be homebrewed, the particulars were turned over to the individual states, and there may remain a handful that still have not taken their anti-homebrewing ordinances off the books. You’ll need to check with your state’s agencies for a determination of legality.

You may be wondering why it took until 1979 to make the homebrewing of beer allowable. The answer goes back almost half a century earlier, to January 16, 1920, and the implementation of the Eighteenth Amendment (the Volstead Act) to the US Constitution, otherwise known as Prohibition. It was this “Noble Experiment,” as President Herbert Hoover called it, that barred the making, trafficking, and transporting of intoxicating beverages. For thirteen years, it was illegal to produce any drink containing more than 0.5 percent alcohol. Unfortunately for the federal government, Prohibition was met with a good deal of public resentment and defiance. It was estimated that over thirty thousand speakeasies existed in New York City by 1929. Nationally, tens of millions of dollars were exchanged in illicit beer sales.

The Volstead Act didn’t eliminate homebrewing. In fact, over seven hundred million gallons of beer were being made yearly by the end of the 1920s. Large breweries remained in business by making malt syrup and other items for the food industry. Curiously, these commodities could be used to make beer.

It was the stock market crash of late October 1929 that indirectly led to the reversal of the Eighteenth Amendment. As the economy soured and unemployment grew, public pressure mounted to legalize beer as a means to stimulate job growth. Franklin D. Roosevelt, a candidate for the American presidency, took up the cause and promised to revoke the amendment, if elected. Within two weeks of taking office, Roosevelt asked Congress for the “immediate modification of the Volstead Act, in order to legalize the manufacture and sale of beer.” On April 7, 1933, it became lawful to produce beer once again.

It became known as “New Beer’s Day.” Sales were so brisk that many regions ran out of beer within hours. President Roosevelt received numerous deliveries of the beverage from brewery owners, thankful that their fermenters again were filled. The formal ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment took place on December 5, 1933.

So, 1933 marked the date by which people could make beer in their homes, right? During Prohibition, people continued making alcohol; that statement can’t be denied. How good it tasted was subject to debate, however. What mattered most was whether the drink was potent. By 1933, the homebrewing of wine and/or beer should have been legalized. Wine, in fact, was included, but a stenographer’s error caused the words and/or beer to be excluded from the Federal Register.

Through the next few years and during the period of World War II, food supplies were limited. Only a few breweries endured and the beer that was produced was low in alcohol and flavor. Men were fighting the war and the beer drinkers within the United States primarily were women. The climate was conducive to the growing of rice and corn, two components that could be used in the brewing of beer, albeit producing a superficial flavor.

Little changed well into the 1970s. Mass-marketing techniques had instilled the belief that beer should be straw-colored with little taste. There were fewer than fifty American breweries in existence and that number was diminishing. However, the customs brought by immigrants were fading and a grassroots movement was arising as people sought a return to earlier times. The only way to drink beer the way our ancestors did was to make it in our own houses. It was this impetus that gave birth to the rise of the “micro” or “craft” brewery.

Two events that furthered this swelling activity took place in California. Fritz Maytag, of appliance fame, purchased the Anchor Brewing Company in San Francisco and vowed to revive the Old World styles of brewing by creating new and different beers. Then, in 1976, the first microbrewery was born in Sonoma, California. Although the New Albion Brewery lasted only six years, it inspired scores of homebrewers to further their craft.

For the person interested in creating homebrewed beer, there are plenty of options. Brewing is in small amounts, generally five gallons at a time, yielding a couple of cases of twelve-ounce bottles. You’ll need equipment necessary to handle the three principal steps of brewing: boiling, fermenting, and bottling. Start with a stainless-steel pot or kettle with a capacity of at least four gallons.

Next, get a five-gallon fermenter, called a carboy. Think of the large jugs that are used to hold springwater. The carboy will need to be secured with a lid, then fitted with a rubber stopper (called an air lock) with a hole from which a clear plastic hose is attached. This will allow the built-up carbon dioxide to escape while protecting the fermenter from airborne microorganisms that could pollute the developing beer.

Finally, get your bottles for packaging. To be safe, about fifty-five or sixty twelve-ounce bottles (or a couple dozen champagne bottles) should do the trick. As convenient as twist-off caps are, pry-off or “crowned” caps will seal better. As a result, you’ll need either a handheld or bench-mounted capper.

Depending on where you live, obtaining these items should not be too troublesome. Many communities have homebrew supply shops where the ingredients, recipe books, and more can be purchased, generally for under a hundred dollars. Staff are knowledgeable and eager to help the novice as well as the seasoned brewer. Many stores offer brewing classes and unique events designed to increase awareness and bring more people into the hobby.

Homebrew clubs are springing up regularly in many locales. Formats and procedures vary. Some clubs have few members and meet informally. Others are large and dynamic, complete with periodic activities and competitions. All, however, welcome those ready and willing to develop their new interest in brewing.

Beer is made of four components: hops, yeast, a malted grain (usually barley, yielding fermentable sugars), and water. The first three may be obtained in varying styles, depending upon what you choose to brew. Most beginners favor packaged kits of malt extract, a syrupy concoction that may also include a container of yeast or added hops. Because this method is so simple, some neophytes shun the process—the decisions have already been made. The true hobbyist enjoys and welcomes having the flexibility to modify each batch she creates.

Consequently, some kits afford the homebrewer the luxury of working like a pro. Specialty grains are included, as are fresh hop pellets, designed to safeguard quality yet keeping the procedure relatively simple. Known as “extract brewing,” this format will satisfy most people, initially producing a highly acceptable beverage.

In time, you might move into a more specialized area known as all-grain brewing. You will need more equipment and time to devote to the process, but the result will rival most commercially available brands.

There are those who would prefer not to make the investment in equipment for a hobby they may practice intermittently. That’s a valid claim. Throughout the United States, Canada, and other countries, there are companies known as brew-on-premise, or BOP, that can take the apprehension out of brewing for the beginner and provide support for the more accomplished brewer.

The concept behind a BOP is simple. The customer creates a high-quality beer at the location of the enterprise. By renting the equipment and buying the supplies, time, space, and recipes, you receive firsthand assistance and expertise. Some BOPs offer wine, cider, or mead preparation as well. Plan on spending a few hours on your first visit as you make your own beer. Oh, don’t forget to give your beer a name and original label design, which you will pick up when you return to bottle your finished product two weeks later. You’ll walk away with a delicious beer that can be modeled after your favorite libation, coming in at a fraction of the price of what you would pay at your local retailer.

In central New Jersey, about seventy-five miles north of my home, is a BOP called The Brewer’s Apprentice. Jo-Ellen Ford, one of the company’s owners, said, “People who don’t know homebrewing can find it somewhat intimidating. We take the fear out of it by trying to recognize the level of the person coming to visit and by making them feel comfortable in what they are doing.” At The Brewer’s Apprentice, you’ll make six cases (seventy-two bottles) of twenty-two-ounce bottles. The fee is dependent on what is produced, although it is possible to have a cost per bottle in the neighborhood of two dollars.

An attractive aspect of brewing at a BOP is the fact that the customer is not responsible for setup or cleanup. During my last visit to The Brewer’s Apprentice, all my equipment was ready as I met my scheduled appointment. What did I make? My daughter Kristin and I selected a holiday spiced beer called Kris-Mas Ale, based on an existing recipe in stock at the business, but altered somewhat to suit our palates.

Nothing is trouble-free. Things can go astray in any process. When you’re homebrewing, cleanliness is of paramount importance. Bacterial contamination can quickly ruin what normally would be a flavorful beer. One way to determine if corruption has taken place is to examine the surface of the beer where it touches the bottle. The presence of sediment around the neck is an indicator of infestation.

Where did the problem originate? Bacterial sources can be found anywhere and everywhere, from your hands to the area on which you are doing your preparations. For this reason, it is mandatory that you soak your bottles and fermenter in a solution of household chlorine bleach and water. Then rinse with hot water.

The siphon hoses you use should not looked stained. Sanitize them prior to handling and replace them when worn. Any plastic equipment must be visually inspected. Scratches are ideal places for bacteria. As your level of ability increases, so do the chances of off-flavors. That topic is best addressed at another time, however.

I heard about a festival where over two hundred different beers were going to be served. What should I expect?

One of the fastest-growing aspects of the specialty beer arena is festivals. They’re gushing onto the scene in virtually every state in this country; most major cities play host to multiple events.

With huge profits to be made, promotional companies are coming out of the woodwork to stage these labor-intensive happenings. Conversely, many beer festivals are labors of love, produced by breweries, enterprising beer aficionados, homebrew clubs, and craft beer organizations. It seems as though everyone is jumping into the fray with a new beer festival once they get wind of the big payoff. If quaffing brew at such an event is in your future, take it from me you need to be prepared. You’ll not only be more comfortable, but also learn more if you show up with the proper accessories and attire. Armed with beer etiquette awareness, you’ll heighten your enjoyment and wow your friends with your suds savvy.

When you’ve decided on a beer festival you want to attend, purchase your tickets in advance. They’re usually less expensive in advance—but there’s nothing more disappointing than being turned away because an event has sold out. Besides, it’s a hassle cooling your heels in line to purchase your ticket at the door when you’re revved up for your first brew.

If you’re taking public transportation, be sure to check the schedule well in advance. And don’t forget to check departure times; you wouldn’t want to be stranded at the corner instead of heading home because the last train or bus departed at 11 pm and you arrived at the terminal at 11:05.

A festival that I once attended was located in a large hall sitting above a parking garage. As attendees exited, there was but one way to turn. The end of the street featured seven police cars with lights flashing, just waiting to test the drivers for levels of intoxication. I would imagine the host city had a busy but profitable evening.

If you aren’t taking public transportation, don’t drive yourself. Treat a friend to a ticket in exchange for being a designated driver. I’ve noted that increasing numbers of promoters are offering discounted or free tickets to designated drivers. There’s no need to feast before the show, but be sure to have some food in your stomach before beginning the tasting session to ease the impact of any lapse in judgment you may make in beer quantity.

Dress casually and wear nonbinding clothes—because after a day of suds sipping, you likely will experience bloating. Above all, wear comfortable hiking boots, walking shoes, or sport sandals. You’ll be on your feet for most of the session, and concrete convention floors and asphalt parking lots are unforgiving surfaces. Shorts or jeans are fine as long as you’ve got plenty of pockets for carrying accessories. As for your shirt, bear in mind that there’s a fair chance that you’ll either spill some of your drink or have someone bump into you. Stout stains look unsightly on a white save the ales T-shirt. If the event is alfresco, bring sunblock and ultraviolet ray-blocking polarized sunglasses that adjust to the changing light underneath or outside the beer tents.

Count on peddlers selling water at two dollars or more a pop, so think about bringing your own. This will be a welcomed, especially if you are outdoors in the hot sun. There should be plenty of photo opportunities should you bring a camera. Are you getting the impression that a backpack or some type of carrying bag is a good idea?

Pick up a festival program upon entry so you can map out your plan of attack. After all, you don’t want to spend valuable time sampling bland or boring beer. Go for the good stuff. Begin with your “ten most wanted,” list because your taste buds will lose their edge quickly. Don’t forget to savor, not guzzle your beer, especially at the beginning when it really hits the spot. Scope out the locations of the restrooms and food court; if necessary, arrange for a rendezvous point for your friends and you.

Don’t forget to bring a pen so you can take beer notes. I write directly on my program, but if you don’t want to mark it up, bring a notepad. If you own any pocket guides to beer, they may come in handy for looking up information. In many cases, the program itself will offer descriptions of each beer served.

Many beer festivals offer very cool door and raffle prizes, so stash some extra cash for buying tickets. Plus, you may want to purchase some snacks, beer ware, or merchandise that you couldn’t otherwise find. Earlier I mentioned wearing clothing with plenty of pockets. That’s where you’ll be carrying your bottle opener, cash, pen, notepad, program, pocket guide, and anything else to which you might want easy access.

Sorry to say this, but you should plan on waiting in line for some things like festival entry, toilet facilities, food, water, and beer. If the festival is well organized, the lines should be at a minimum. Pushing and shoving at beer booths never is acceptable. Likewise, after you’ve gotten your beer, move well away from the table so others can get their samples.

Expect to receive small servings of beer, usually two or three ounces each. The rules may vary from show to show, in accordance with the organizers or state laws. It may not seem like much, but it adds up to a lot of beer quaffing. If you are served a beer you don’t like, don’t hesitate to dump it. There usually are buckets at the serving tables for that purpose. Why get one step closer to your personal limit drinking marginal beers? A select few promoters offer tokens for each desired beer. In this scenario, you can expect to receive six-ounce-or-larger servings that you can split with friends if you’d like to sample more drinks through the course of the event.

Children are inappropriate at beer festivals and generally are prohibited from entering the area. Find a sitter or ask Mom or Dad to take care of them. This is an adult event and is not for families. Dogs are usually allowed at outdoor festivals (check before bringing Fido), but I’ve seen far too many animals suffer from heat prostration and sunburn from being led around on hot pavement by their unsuspecting masters.

Take a few minutes to ask questions of the brewery representatives or the brewer himself, if he’s there. The more you learn about beer styles, the brewing process, and historical idiosyncrasies of beer and breweries, the richer and more fulfilling your beer experiences will be. The people with whom you’ll speak will appreciate it, too, and may show you some extra courtesy and kindness. Of course, it goes without saying, but a please, a smile, and a thank-you or a compliment about a beer will go a long way with busy, tired volunteers and the serving team.

Once you’ve attended the festival and you feel up to it, evaluate your experience. Was your game plan a good one? Would you have done better to have visited the food court early before the lines developed? Did you bring your pocket guide but never look at it? At your next festival, use the strategies that worked and ditch the ones that didn’t. Before you know it, you’ll be a savvy beer explorer.

I bought a cold case of beer, but by the time I got home it was warm. Will this damage the flavor?

Temperature variations can be hazardous to a beer’s health, but I wouldn’t be overly concerned by one episode of cold to warm to cold. Having this occur frequently certainly affects freshness, and the flavor will be less than what you expected. Get the beer home and keep it in a constant cool temperature, hopefully removed from as much light as possible, and enjoy your purchase.

I bought a case of beer that tasted bad. Can I return it?

That’s a complicated question that needs explanation. If I went to the supermarket and purchased a can of soup that I didn’t like, should I be able to return it? In theory it sounds nice, but it’s just not practical from a business standpoint. Not liking the flavor is an unacceptable reason for a store return. Conversely, buying a product that is defective should afford the customer the option of an exchange or refund. But how do you recognize a faulty beer as opposed to a flavor you don’t fancy?

Some people feel that an overly bitter beer must be bad. Bitterness comes from hops, and the amount and type of hops influence that bitterness. There are beers on the market today that are very aggressive, in terms of that ingredient, by design. So bitterness can’t truly be a mitigating element.

The level of carbonation also must be tossed aside as a warning sign. Carbonation will vary from style to style, and certain beers have almost no bubbles. There is a measure of truth to the theory that those beers with a high alcohol content, such as barleywines, have little carbonation. Completely flat beers are rare.

The presence of solid particles, sometimes called “floaties,” is unattractive and unwanted, but not unhealthy. Don’t mistake them for the cloudiness associated with an unfiltered beer (see below). Floaties are globs of protein that can occur when a bottled beer is old. They should be visible through the bottle. The taste may be compromised, so that may be reason for a return visit to your vendor. Floaties don’t materialize often with domestic brands, especially those that have a brisk turnaround time.

Sourness is a prized trait in styles of beer such as those in the lambic family. You’ll notice that quality in wheats, as well. Beers of this sort are an acquired taste, and if you’re currently drinking light American pilsners, for example, you probably won’t accept the drastic change in taste these beers present. If I bought a mass-marketed domestic lager, on the other hand, and picked up on sourness, I’d know the sample was infected.

Have you ever popped the top off a bottle only to release a gusher? It could signify a beer that has bacterial contamination. Why does this happen? In a bottle-conditioned beer, the yeast continues a little bit of fermentation within the bottle. If tainted, the bacteria will not stop their work, resulting in an escalation in pressure. If your bottle is corked, treat it as you might champagne and point it away from people. I once saw a cork poke a hole in a ceiling tile when released.

When you have a gusher, smell the contents. If you detect a vinegary aroma, well, it’s probably bad. If there is no offensive odor, take a sip and, if it’s satisfactory, go with it.

A common description for beer that is past its prime is that the liquid is “skunky.” Sounds appetizing, huh? Exposure to light can cause this foul sensation. Don’t worry, it’s highly noticeable.

Exposure to oxygen can cause off-flavors of wet cardboard, mustiness, or sherry. What a cross section, to say the least! In aged beers, the latter trait can be enjoyable; in others it is offensive. Return it.

I once attended a beer festival in which a specific brand of a noted brewer’s beer tasted of butter. Butter and butterscotch taste good and sometimes are desirable, but they’re an indication of a by-product of fermentation and are not how the beer is intended to taste. Low levels are not necessarily bad, but higher ones point to a beverage that is defective.

Another form of bacterial infection is DMS or dimethyl sulfide. Your beer will smell like shellfish or cooked vegetables. I’ve seen evidence of this in quite a few homebrews.

Also common to homebrews are phenols from fermentation. The beer will smell like an adhesive bandage or possibly medicinal or clovey. You must be aware of the style of beer, as certain wheat-based beers are intended to have this trait. In others, though, it is a sign of bacterial infection.

Doesn’t beer make you fat?

The culprit is the calories coming from alcohol. But there are calories in almost everything you drink. Think of the last time you were at a bar. There’s a good chance there were munchies present, probably chips, peanuts, pretzels, and the like. What do they have in common? Fat, salt, and calories. Try eating just one peanut.

Look at the person’s lifestyle before blaming beer for causing a weight problem. Is that person sedentary or active? At a recent speaking engagement, one member of the audience asked, “You must not drink much beer. You’re not overweight.” I’m six feet tall and weigh 180 pounds. Of course, moderation is the key, as it is with anything. I average anywhere from one to three beers daily.

Stew Smith is a former Navy SEAL and current writer who appeared with me on Beer Radio, previously heard on the Sirius Satellite Radio Network. Stew offered the following advice: “There is no reason why you cannot have six-pack abs and still drink a six-pack a week. Once again, excessive beer drinking is not recommended by anyone in the health industry. If you simply enjoy drinking beer and are serious about your health, moderation in drinking alcohol and eating good foods, combined with habitual daily exercise, is your ticket to reaching your goals.”

Alcohol contains no fat or cholesterol, although the nutritional value is dependent upon the type of drink. For my money, I’ll stick with beer. In its simplest form, it contains only water, hops, yeast, and grain.

Aren’t low-calorie or light beers just watered down?

The concept behind reduced-calorie beers had its start around World War II when breweries attempted to attract women. By the 1970s, there were only a few dozen breweries left in the United States, and most made the same bland stuff. I’m not going to say that low-alcohol versions never were solely diluted. In fact, there was one brewer who, in his six-pack, packaged five bottles of his “regular” brew along with one bottle of carbonated water, asking people to make their own.

The construction of a low-alcohol beer can take as much effort as that given to any other variety. Raw beer is called wort (pronounced wert). It’s thinned in the fermenter, but the addition of yeast leads to different flavors and a lower alcohol content.

Some breweries add enzymes to the wort to break down the sugars. Altering the fermentation or adding rice or corn will provide cheap fermentables, but will produce what essentially is a tasteless product, rather high in calories. What happens then is that watering down takes place. So, the question does have a degree of truth.

The first light beer was actually produced in the late 1960s at the Rheingold brewery. The creator of Gablinger’s Diet Beer, the late Dr. Joseph L. Owades, once said, “I asked people why they didn’t drink beer. The answer I got was twofold. ‘One, I don’t like the way beer tastes. Two, I’m afraid it will make me fat.’ It was a common belief then that drinking beer made you fat. People weren’t jogging and everybody believed beer drinkers got a big, fat beer belly. Period. I couldn’t do anything about the taste of beer, but I could do something about the calories.”

The formula for light beer ended up being used as Meister Brau Lite. Miller Brewing later bought Meister Brau, tweaked the blueprint just a bit, and rebadged the beer a few years later as Miller Lite. Bring in a snappy advertising campaign that included actors, comedians, and athletes and you had a breakaway beer in the mid-1970s.

Isn’t a beer served in a frozen mug the best?

It is if you don’t want much flavor. Then again, many mass-marketed and low-alcohol brands lack intense flavor. Think of the leftovers from the meal you had the night before. When you go to your fridge and eat it, the flavor intensity just isn’t the same because the food isn’t at the ideal serving temperature. The flavor of most well-constructed beers emerges at milder temperatures. Also, as the ice from a frozen mug melts, you are diluting your drink.

I saw a layer of something in the bottom of my bottle. Has it gone bad?

If it’s a bottle-conditioned beer, probably not. As was stated earlier, the substance you see is yeast, added prior to bottling to continue the fermentation process. You can deal with this in a couple of ways. When pouring, you can simply decant the liquid, leaving those last few ounces. Or you may opt to gently swirl the bottle, letting the yeast blend a bit.

Remember that those final couple of ounces will look and taste different from your initial pour. When I’m serving a bottle-conditioned beer at a formal tasting, I attempt to mix the yeast in the bottle; otherwise I omit serving that final pour.

Yeast is nothing more than B vitamins, making it a very healthy drink. If the concept of bottle-conditioned beers is foreign to you, I suggest drinking those last couple of ounces to see if the taste appeals to you. Be aware that the beer will appear murkier than the initial glass you served; if aesthetics matter, you may not be impressed. By the way, bottle-conditioned beers should be labeled as such.

If you are drinking a filtered beer and see solids, I’d be concerned. You probably have a relic that should be tossed aside.

Is it true that bock beer is produced when they clean the bottom of the barrel?

This story has been going around for decades; it’s one of the first I heard, long before I got into this industry. Nothing could be farther from the truth. This style of beer, German in origin, comes from the German word that refers to a goat. That’s why you’ll often see images of that animal on a bottle’s label.

Bock beers are strong lagers, richer and somewhat darker in color because of the amount of grain used.

Should a wedge of lemon be served with a glass of wheat beer?

I believe the practice of adding a slice of lemon or lime started in Germany in the 1960s and spread to this country some twenty years later. Although there are some who wouldn’t have their beer served in any other manner, I opt to drink without it. A hefeweizen or a Belgian wit already has elements of citrus and spices in it; I don’t want the aroma and flavor altered in a way the brewer didn’t intend. Also, adding citrus is one good way to wipe out any foam, one of the attractive components in a wheat beer.

What I strongly object to is when a bartender serves a wheat beer with the wedge added before asking if that’s how the customer wants it.

How about the addition of fruit to the brew? It seems strange, but I’m noticing more of these beers being sold.

During the colonial era of this country, brewers used anything that would provide yeasts to perform their magic. Many times, this meant using locally grown produce in lieu of imported barley, an item that was heavily taxed. There is documentation going back to 1771 of commercial recipes that include parsnips, spruce, and pumpkins.

Although some of the early beermaking recipes look a bit strange by modern-day standards, items like corn and molasses were staples; to this day, most large breweries continue to use corn as an inexpensive way to augment production. A brewer once told me, “Most good beer should be made with barley, in the same way that good hamburgers are all beef. Barley is expensive, and the more fillers that are used, the bigger the profits.”

Fruit beers are what the name implies: beverages with fruit and herbs added during the brew. Years ago, the use of fruit to enhance flavor was common even before hops were found to be a preservative for the drink.

At virtually any brewery, the decision to use produce in the mix is subject to the decision of the brewer and the type of beers desired. Tom Baker, owner and brewer of Earth, Bread & Brewery in Philadelphia, the now-defunct Heavyweight Brewing, once developed a brew that he identified as Ch-Chuck. No, he doesn’t have a speech impediment; rather, Ch-Chuck was the second iteration of a beer once called Chuck (named because he “chucked” various ingredients into the concoction). Ch-Chuck picked up where the original left off based on the inclusion of twenty pounds of sour cherries and the juice into the fermenter.

Another brewer took a recipe developed as a homebrewer and transferred it to his brewery. Chocolate Cherry Imperial Stout was a beer that used Hershey’s cocoa in the boil with cherry puree added. That brewer said, “This is something I wanted to do professionally. I do believe, however, that fresh fruit should be used whenever possible, instead of extract, which gives an artificial taste.”

Not all breweries opt for fruit-infused beer. One West Coast brewer told me, “I just don’t want to brew with fruit. Plus, I don’t like to brew what I don’t drink.”

When looking for a fruit beer, you may find the words kriek (cherry), framboise (raspberry), and pêche (peach), as these are three of the most common fruits used.

Other fruits are used in brewing, as well. You can find some tasty beers with blueberries, cranberries, apricots, black currants, strawberries, pears, apples, and more. During autumn, there are several remarkable pumpkin beers to be found. And now, these beers are being produced worldwide.

Fruit beers make invigorating aperitifs. If you’re pairing foods, consider chocolate desserts, tangy cheeses, mussels, and salads in a fruit-based dressing. Alcohol content may vary, but the upper limit of most of these beverages seldom exceeds 6.5 percent alcohol by volume.

They may not be for everyone, but many people find fruit beers to be unique and refreshing. And they just may change your perception about this old, yet complex drink, originally built from just a handful of ingredients.

Organic foods are everywhere. Will we ever see organic beer?

Look no farther than the shelves of your favorite beer vendor. Organics are here and are doing very well, thank you. But first, let’s define what it means to be organic.

In the late 1990s, the US Department of Agriculture developed the National Organic Program to regulate and inspect food and beverage products that seek the claim of being organic. This program states that “before a product can be labeled ‘organic,’ a Government-approved certifier inspects the farm where the food is grown to make sure the farmer is following all the rules necessary to meet USDA organic standards.” There is no claim, of course, that organically prepared items are safer or more nutritious than those commercially prepared. As it applies to the making of beer, the grains and hops used must be grown and handled without any toxic chemical inputs. To then be certified as organic, the fields where barley or wheat (for example) are grown are done, as well as of production and processing area. Regular soil and water testing may occur to make certain that benchmarks are being met.

Adhering to the strict standards demanded by the program is not easy and takes time and money. Consequently, there exist beers on the market today that probably are organic; they just can’t advertise as such. But the demand for food and beverages of this ilk is growing at a feverish rate, far exceeding the growth of traditional beer sales.

Probably the most recognizable name in organic beer is that of Wolaver, owner of the popular Otter Creek Brewing Company. Certified as using at least 98 percent organic ingredients, Wolaver’s can be found in most, but not all states. As for flavors, the company has a wide array, brewing a wheat, an India pale ale, a brown ale, and an oatmeal stout, among others.

In England, the Samuel Smith Old Brewery at Tadcaster makes an Organic Ale and Organic Lager. Both are certified by the National Organic Program. You’ll appreciate the serving size, as both come in 18.7-ounce Yorkshire pint bottles.

Jon Cadoux is the founder of the Peak Organic Brewing Company in Portland, Maine, a brewery that was unveiled in 2006. He was quoted as saying, “We believe that using barley and hops that are grown without toxic and persistent pesticides and chemical fertilizers makes our beer tastier and more enjoyable, both for you and the planet.” He initially released three flavors: pale ale, nut brown ale, and amber ale. All are extremely flavorful.

The claim that organically constructed beer tastes better is subjective, although a representative from a brewery making these beers said the following: “There are no chemical residues to get in the way of fermentation. My people feel that using a grain free of pesticides leads to cleaner brewing traits, leading to a more complete drawing out of sugars.”

The movement to organics has caused Anheuser-Busch to get into the game. You may have seen a couple of its beers packaged under the Wild Hop and Stone Mill labels. Try to find the name Budweiser on those bottles, I dare you.

There are a few revolutionary brewers who are moving to the forefront of the movement, but the success of organic beers will depend on several factors, including concern for the planet and, of course, flavor.

Why aren’t microbrewed beers canned?

That’s not a bad question! An increasing number of breweries are doing just that, realizing that canned beer offers certain advantages over bottled. One obstacle that needed to be overcome was the leaching of a metallic taste into the beer, a valid consideration. Nowadays, cans are lined with a water-based polymer that protects the beverage from the metal. Although there can be other reasons why canned beer might taste tinny, it should not be because of the process itself.

Think of the advantages that cans have over bottles. First is cost. Manufacturing a can costs less than does making a bottle. Any savings to the brewer can help the consumer. Cans are easy to carry and less likely to break than bottles.

There are places that allow the sale and use of cans, as opposed to bottles. In fact, there are numerous public places that have outlawed bottles for various reasons.

What destroys beer? Your first response should be exposure to light. Need any more be said about the benefits of canning?

There are a couple of other factors to consider. One is image. A generalized statement would suggest that the typical craft beer drinker purely expects her beer in a bottle, equating cans with those beers from the large breweries. Well, that’s slowly changing. The Colorado-based Oskar Blues Brewery has been marketing its Dale’s Pale Ale and Old Chubb Scottish Ale in cans and is enjoying a successful run. I’ve had both and can honestly state they are fine beers.

Sly Fox Brewery, with multiple locations in Pennsylvania, now is selling more beer in cans than in bottles, in part based on customer interest. Adding this aspect of packaging has led to double-digit increases in annual sales. The fact that brewer Brian O’Reilly’s beer is damn good doesn’t hurt, either.

Initially, I had to deal with the visual impact of a can and the mental image of what is inside. Unfortunately, I’ve noticed a few retailers restricting these beers to the bottom shelf, far from eye level, an area that tends to decrease sales.

Barrier number two involves the current state of bottling. Notice the amount of beers that are being presented in large bottles, those 750ml monsters that once were thought to be reserved for wines. Appearance is important to many brewers, who take pride in how their bottles look, including label design. Browse through the aisles at your liquor retailer and look at vodka bottles, for example. Many are beautifully shaped and constructed. It kind of reminds me of the days when record albums were sold and I bought one solely on how it looked.

I’ve not seen beer bottles offered in terribly unusual shapes yet, nor do I feel that this is likely to happen at anytime soon. Then again, never say never.

Exposure to light damages bottled beer. So how do you buy beer from a store that obviously is lighted?

One of the most common concerns people have about buying of beer in bottles is spoilage. Everyone has his own ideas as to how to reduce that risk, but certain facets are unavoidable. Much is made of the color of a beer bottle. It’s believed that the darker the bottle, the less likely it is that the contents will be jeopardized by ultraviolet rays. You are likely to find bottles that are shaded amber or green, or are clear; most are amber. Why the differences? Mostly because of marketing. Miller Brewing, for example, is associated with clear bottles; Heineken is correlated with green. I’ve heard it said that green or clear bottles will cause the beer to turn bad more quickly than amber and I’ve seen data that support that claim. Yet decades ago, patents were issued to create light-protective green glass, a process that can block or reduce damaging rays. Furthermore, some companies have worked with the hops included in the brewing recipe to make their products more stable when exposed to light. More recently, Beck’s introduced a clear glass bottle that protects the beer from light. During processing, the glass is tailored to improve its light-absorption qualities, better defending against flavor changes.

Another key is in whether the beer you are buying is pasteurized. Most beer is pasteurized, and that process helps prevent unwanted changes from transpiring quickly. Again, remember that many craft beers are unpasteurized and unfiltered, meaning they are susceptible to unwelcomed variations.

Here is how I attempt to partially get around the artificial lighting concern. When buying beer, I do not take the package that sits at the front of the shelf; I opt for the second or third one. It’s likely to be a bit more in the dark and receives less direct light.

I had a bottle of [fill in the name of a non-American brewed beer] in [fill in the name of a country other than the United States] and it tasted much better there than here. Why is that the case?

I hear this one all the time. There is no plot to offer cheaper and better versions of beer outside America. Differing versions of certain beers are sold, however. Take Guinness, for example, a beer that frequently is found on tap and in restaurants. There are assorted types of this brand produced and distributed worldwide. Are you familiar with Guinness Foreign Extra Stout, Guinness Red, Guinness Special Export Stout, and Guinness Bitter? You are if you’re an extensive traveler or have special friends who bring these beers back for you.

Usually this concern arises when you’ve found that great beer you love while at the Caribbean Islands. It just wasn’t as good here. Of course, at the time you were sitting on the beach on a sunny eighty-five-degree day, enjoying a relaxing vacation. You drank your next bottle at home when the kids were fighting and you’d just found out your checking account was overdrawn. Similar scenarios?

We can even apply this to domestic beers. Let’s use the Boston Beer Company, makers of the Samuel Adams lineup of beers, as an example. If you think their entire portfolio was brewed in Boston, check again. Sam Adams is produced in several American cities, including Cincinnati. Think of Coors and its “Rocky Mountain Spring Water,” a wonderful marketing campaign. In some parts of the country, buying a Coors product was difficult, going back thirty years or so. Elitism developed. Then Coors opened a plant in Virginia. The Rocky Mountain water? Well, it’s somewhat true. The beer was shipped eastward in a highly concentrated form, then blended with local water to reduce costs.

Why do the British drink warm beer?

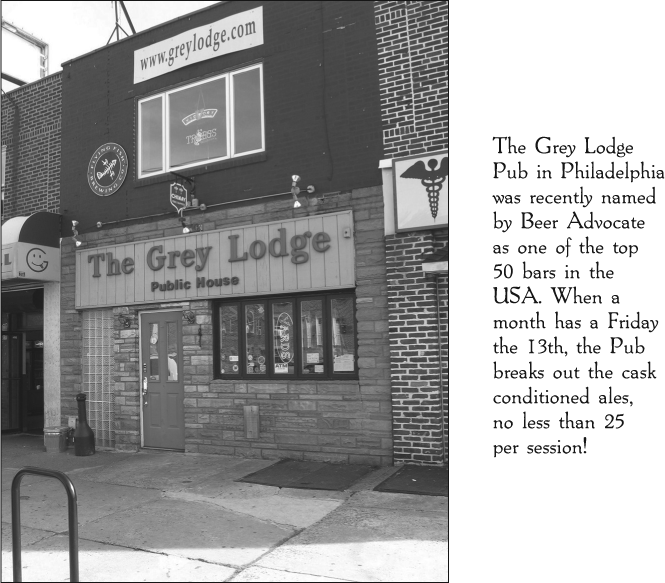

They don’t, but compared with Americans, you might make a case for that assumption. Most domestic drinkers prefer their beverages ice-cold, with the exception of those who have made the move into the world of more flavorful brews. In much of Western Europe, cask-conditioned beer is popular—meaning beer that has undergone a second fermentation in a cask (somewhat like a keg). Because yeast is added, fermentation of remaining sugar continues, resulting in the release of some carbon dioxide and a progression of flavor development. The practice of serving cask ales is becoming more prevalent in the United States. There now are brewpubs and bars that sporadically offer cask nights. Philadelphia’s Grey Lodge Pub hosts an event referred to as “Friday the Firkinteenth.” This somewhat quirky title reflects a happening that only takes place on a Friday the thirteenth of a month. On that date, casks of different beers are available for sampling. Fans of the Grey Lodge anxiously check their calendars near the beginning of each year and schedule their pilgrimages to this extremely popular site. Incidentally, a firkin is a quarter of a barrel and is considered the norm for serving cask ales.

Is barleywine considered beer or wine?

The biggest, boldest, and baddest of all beer styles is barleywine, a beer that often reaches the double-digit level in alcohol. Originating in England around 1900, barleywine is fermented and derived from grain and not fruit, making it a beer. The “wine” portion of the style comes from the fact that the beer is about as strong as wine. These beers conventionally show themselves during winter months and are meant for sipping. Carbonation is relatively modest.

Barleywines are fruity and warming, great to sip after a meal or while sitting before a fire. The color can range from amber to dark brown. English versions tend to be sweeter and less alcoholic than their American counterparts, but all are fine candidates for cellaring. Like wines, some barleywines are perfectly acceptable for years from bottling.

The naming of barleywines seems to inspire resourcefulness at some breweries. Here’s a representative sample: Sierra Nevada Bigfoot, Anchor Old Foghorn, Dogfish Head Immort Ale, Horn Dog, Insanity, and Old Knucklehead.

I was reading the menu of beers made at my local brewpub and saw columns labeled ABV and IBU. What are they?

ABV stands for “alcohol by volume”; IBU refers to “international bittering units.” Stated as a percentage, ABV gives the drinker an idea of the amount of alcohol in a particular drink. The tricky part is in recognizing whether the figure is listed as “by volume” or “by weight” (ABW). There’s a difference. If you know the former, multiply that number by 0.8 and you’ll get a good approximation of the measurement by weight. Conversely, taking the alcohol by weight and multiplying it by 1.25 will give you a good idea of the alcohol by volume. For example, a beer that comes in at 5 percent ABW, multiplied by 1.25, will equal a 6.25 percent ABV beer. To compute “proof,” commonly used with spirits, double the ABV. A 13 percent barleywine is 26 proof.

It’s a shame there is no standard for reporting the amount of alcohol in a beer, nor is there a law requiring breweries to do so. Apparently, the stance of the government is that labeling how much alcohol is in a certain beer would encourage drinkers to look for the strongest beverage. Personally, I feel that knowing beforehand what I am about to drink is valuable, especially if I plan on driving. I recall attending a beer dinner in the early 1990s in which six beers were served and all registered at least 9 percent ABV. No bottles were labeled as such, nor did the host identify these valuable numbers to the diners. By the end of the evening, he had a room of very happy people, many of whom were, unfortunately, taking to the roads.

IBU is a generalized view of how bitter a beer may be, because of the presence of hops. This number can be a bit misleading, however. A low-alcohol American lager can have an IBU reading as low as 5; an India pale ale can reach 65, and certain barleywines, especially those made in the United States, can reach 100. But would you say that the barleywine tastes more bitter than the IPA? Probably not. The deciding factor is in the amount of malt used. Remember that barleywines have an elevated amount of alcohol when compared with an India pale ale. Without a much higher quantity of added hops, the beer would taste syrupy sweet and be unpalatable. So if you’re using IBUs to determine of a beer’s bitterness, be certain to compare it with its ABV or ABW.

Occasionally you may see another set of letters attached to a beer: OG or “original gravity.” Sometimes this is called “starting gravity” or even “specific gravity.” If you are having a flashback to your high school chemistry class and feeling a bit stressed, please relax. Here’s all you need to know. Water has an original gravity of 1.000. A developing beer’s original gravity will be higher than that of water because it contains more fermentable and unfermentable materials. In other words, it’s denser or heavier than water. After fermentation is completed, the starting number will drop close to that of water. As an example, I know of a brewery that makes a hefeweizen and a barleywine with original gravities of 1.047 and 1.091, respectively. The alcohol by volume of each beer is approximately 5 percent and 10 percent. What I intentionally omitted was the final gravity (FG), the reading of the beer’s density after fermentation. For you math whizzes, there is a formula to calculate a good approximation of beer’s alcohol by volume. It is: OG – FG × 131. Any serious homebrewer will be happy to tell you about the computations.

In summary, the higher the original gravity, the more alcohol in the particular beverage you are drinking.