6

I HAVE SAT FOR HOURS on the bench in front of the house – it’s a plank of driftwood on a pair of stones – watching Donald MacSween trawling for scallops (or clams as they are called in the Hebrides) in the waters a mile or two away just south of the Galtas. He has a new boat now, the Jura, but in the 1980s, it was the Favour, a steel thing, not, it has to be said, the greatest beauty that Scalpay has ever known, painted red and white, with its name in huge letters on the wheelhouse.

Sometimes, he and Kenny Cunningham, his crewman also from Scalpay, went on deep into the night and on a quiet evening all you could hear for hour after hour was the groaning monotone of the diesel, a slow surging in its note, as the Favour pulled the heavy clam dredge across the sandy floor of the Minch fifteen or eighteen fathoms below them. It was long work and by the late 1980s most of the scallops here had been fished out. Every few hours Donald and Kenny would haul up the dredge and pick one or two of the valuable shells from its heavy metal mesh. Money was short.

The dredge always brings up other things: boulders, wreckage,: the odds and ends with which the floor of this littered sea is covered. Early in 1991, they spotted a piece of straightish, gold-green wire about two feet long. It had been caught up in the gear. Kenny picked it out and thought little more of it. It was a curiosity.

The length of wire spent a year or so alongside the spanners and heavy screwdrivers in the toolbox of the Favour. Fishing boats are high-maintenance creatures. Donald leaves for sea at four every morning, a little later in the winter, and is back in the North Harbour at Scalpay by early afternoon. But that is not the end of the day: there is always several hours of mending and maintenance to be finished. The tool box is as critical as the rudder. Month after month the wire was shoved aside by hands looking for a wrench or a jemmy. At one point it was hung on a hook in the wheelhouse, remaining there for the summer.

One Sunday evening, Kenny happened to be watching the Antiques Roadshow on the BBC. A woman produced a piece of jewellery which seemed to resemble the wire that had been dredged up the previous year. Cunningham was going to Glasgow for a wedding and so thought he might take it to an auctioneer’s to get a valuation. At Christie’s, he brought the wire out of the deep, inside pocket of his jacket. It was in the shape of a walking stick, a long straight section with a curve at the top. Miranda Grant, Christie’s gemologist, who had done a thesis in early Celtic jewellery, was called to the desk. She was mesmerised by what she saw and took it in her hands. Kenny said he thought it might be gold because it had been in the sea but was quite uncorroded. It was only gold, wasn’t it, that could lie in the sea and remain unaltered? Without thinking quite what she was doing, on automatic pilot, as she says, Miranda Grant grasped the object and bent it into the shape she thought it should have, a looped circle. The wire was of very pure gold, probably between twenty-two and twenty-four carat, and in her hands, it was softness itself. ‘It went like butter,’ she said. She suggested quite calmly that it should go straight away to the National Museums in Edinburgh for a further view. Cunningham left it with her and the next morning she took it there in a briefcase.

Trevor Cowie, the curator in the National Museums, ‘almost died’ when Miranda Grant brought the object out of her briefcase. The piece of soft gold wire was the only surviving late Bronze Age gold torc ever to have been found in Scotland. Another three had been recorded in the nineteenth century (from Edinburgh, Culloden and Stoneykirk in Wigtownshire) but were now lost, one certainly and the others probably melted down for their gold. This was the only Scottish survivor of a kind of body ornament, probably made in about 1200 BC, for the neck or, if twisted into a double spiral, the upper arm, of a prince or priest or chieftain. It is a kind of jewellery which in a sparklingly twisted golden trail has been found scattered throughout Celtic Europe: one or two from near Carcassonne in the stony world of the Mediterranean, another in the Pyrenean foothills south of Toulouse, one from Jaligny in the wide, flat meadowlands of the Bourbonnais in central France, one from the orchards of Calvados in Normandy, another from the bed of the Seine in Paris itself. The trail runs on through Brittany and the Channel Islands, across wide swathes of southern and eastern England, one found in the Medway at Maidstone, another at Mountfield in the Sussex Weald and a cluster of them in the Fens. Their heartland is in Wales and across the Irish Sea. Two were found at Tara, in County Meath, the capital of the Irish High Kings, and one at the Giant’s Causeway in Antrim. The gold of this torc is probably from Wales or Ireland, or perhaps a combination of the two. Throughout the Bronze Age the metal was extensively recycled.

Excitement rippled through the archaeological community and the MacSween and Cunningham households. (Although scarcely beyond them: this is not the kind of news which is immediately shared on Scalpay.) But whose was it? The proprieties had to be observed and the assumption made by the authorities was that this object came from a wreck. The wreck might have been more than three thousand years old but it was still a wreck. The government employs an officer in ports all around the British shores with the title ‘Receiver of Wreck’. Wreck, in this instance, is not a description of a ship but of a category of goods, a cousin to flotsam (goods washed off a ship at sea and floating) and jetsam (goods deliberately thrown off a ship to lighten it in a storm).

‘Finders,’ the Receiver of Wreck’s official document states, ‘should assume at the onset that all recovered wreck has an owner.’ Finds must be ‘advertised as appropriate to give the owner the opportunity to come forward and claim back their property. If no owner is found within one year from the date of the report, the material becomes unclaimed wreck. In the majority of cases the finder is then offered the material in lieu of a salvage payment.’

For a year, the torc discovered by Kenny Cunningham and Donald MacSween remained in the custody of Her Majesty’s Receiver of Wreck, Stornoway, waiting for a naked, dripping Bronze Age chieftain to walk into his office, next to the Fishermen’s Co-Op a few yards from the town quay, and claim it as his own.

He never did and the torc became the possession of the fishermen who had found it. There was a symbolic struggle between museums. The National Museums of Scotland, then in the process of creating the new glamorous Museum of Scotland in Chambers Street in Edinburgh, wanted it for their new displays. It was of national importance, they could argue, and so should be shown in the national capital. The Museum nan Eilean, the Museum of the Western Isles in Stornoway, forever feeling that whatever was marvellous from the Hebrides was whisked off to Edinburgh, whatever second-rate left behind, also wanted it for their own exhibition. In the end it came to money. The Western Isles Council was still recovering from the financial catastrophe they had suffered in 1991 when £23 million of ratepayers’ money had been lost. The Council’s funds had been deposited with the high interest, high-risk Bank of Credit & Commerce International. When the bank collapsed, there was certainly no money for archaeological acquisitions. Stornoway couldn’t afford the torc and nowadays there is a small photograph of it in the Stornoway museum on Francis Street. The real thing was bought by the Edinburgh museum, for a sum which Donald has asked me not to mention, which was split half and half between him and Kenny and which was substantial enough to have ‘paid off the debts’. It was certainly the best day’s fishing either of the men had ever had. Their catch is now in a high glamour setting in Edinburgh, shut behind glass in a display case made by Sir Eduardo Paolozzi in the form of an aggressive automaton, his hands raised and his aspect fierce, the torc both displayed and protected by his strange and armoured body.

Can one say any more about this wonderful and mysterious object, the most valuable thing ever to have come to the Shiants? Certainly you can tell nothing from the form in which it is so carefully preserved in Edinburgh. That is simply the shape given it by Miranda Grant in her moment of ecstasy. It has no historical significance. But you can at least see that the torc is beautifully made. A square, golden rod, a single ingot hammered to the correct length, has been fluted on each of its four sides so that the four ridged edges of the rod stand out. It has then been held at both ends and carefully twisted, so the four edges of the bar now spiral around it as a continuous decoration. To the ends of this twisted rod two long plain terminals have been welded or soldered, although the junction is carefully concealed within a tiny gold cushion. Those terminals are made so that they will hook around each other, the torc itself providing the spring and elasticity which keeps them locked together on the neck or arm of the wearer.

It is a delicate thing. Alongside it in Edinburgh are examples of neck ornaments from other times and other parts of Scotland. Many of them take the form of vast money display: the huge, early Bronze Age golden collars from Dumfriesshire, which are positively Incan in their scale and vulgarity, or the extraordinary Pictish silver neck-chains from the centuries before the Vikings’ arrival, heavier than dog-collars, perhaps made from melted down late Roman silver, paid to the Picts as protection money; or even the massive Norse brooches and neck rings from the hoard stumbled on in the nineteenth century at Skaill in Orkney, in which the brooches are six inches across, normal objects inflated as a display of power.

The Shiant torc is not like that. There is a simplicity and subtlety to it which perhaps means that it is not intended as a form of dominance. It is meant to decorate rather than to impress and would have graced the body which wore it. One might even have taken a moment or two to recognise that the person was wearing it. This is, in other words, a civilised and not a violent thing, as subtle as scent. Its presence here seems to me as exotic as a silk dress on a cliff face, Audrey Hepburn, somehow, en route to the North Pole. No torc of this kind has ever been found this far north.

What is it doing here? Were the Shiants themselves in the Bronze Age a place of significance, to which objects of this kind would naturally gravitate? Or was it washed it here from somewhere else by the currents of the sea? Did it go down with a boat that was wrecked on the Galtas? Was it dropped overboard by mistake? Or was it, perhaps, deliberately thrown in?

It seems wildly unlikely that the Shiants in the Bronze Age were a place of any importance but how could I tell? The past is so opaque here. Did I really want to poke around in the body of the Shiants? Wasn’t it better to leave things in a state of uncertainty?

For a long time I hesitated. One of the reasons I loved the Shiants was that they were away from the world of definition. When I was a boy, the masters at school would always say, whenever I produced any work, ‘Yes, Adam, but have you thought it through?’ The answer would invariably be no. I never think things through. I never have. I never envisage the end before I plunge into the beginning. I never clarify the whole. I never sort one version of something from any other. I bank on instinct, allowing my nose to sniff its way into the vacuum, trusting that somewhere or other, soon enough, out of the murk, something is bound to turn up.

I’m wedded to this plunging-off form of thought, and to the acceptance of muddle which it implies. Something that is not preordained, that hasn’t even envisaged the far wall before it has started building the near one, has the possibility, at least, of arriving somewhere unexpected. There’s a poem by the American, Denise Levertov, with the marvellous title ‘Overland to the Islands’, which in four words makes a bright little capsule of that frame of mind. Thinkers-through would never go overland to the islands. They would never expect to find the islands there. But Levertov, drop by drop, takes you out, on a mapless walk full of suddenly grasped fragments, each to be treasured for the way it is stumbled on, out of nowhere, with no context. ‘Let’s go,’ she says, ‘much as that dog goes, / Intently haphazard …’

And she does, musically, elegantly, chancily, discovering the Mexican light, the iris ripples on her dog’s back, and his nose sniffing for the next thing.

There’s nothing

the dog disdains on his way,

nevertheless he

keeps moving, changing

pace and approach but

not direction – ‘every step an arrival’.

If I were to erect a motto over the Shiants, I could do worse than almost any one of those lines. ‘Every step an arrival’ should be on the door of the house. Give everything a sniff.

The dogs love the Shiants. It is a dog’s world of not thinking through, of beautiful incoherence and the thing seen for itself, the rocks and mud under the dog nose, that travelling to and fro along the margins of a path, an excited ‘What next?’ as the motivating force in life, a stodgelessness, an inability to plan.

All of this is the opposite of the fashionable qualities. The modern world likes the complete, the systematic, the self-sufficient, the clarified and the unabsorbent. Softness and haze are things to be cleared away. Hard truths are to be revealed by stripping back obscuring surfaces. The landscape you see, with all its fluff and uncertainty, only hides the bones of a lurking reality which archaeology or psychotherapy will all too happily cut back to. Suggestiveness and ambiguity, the half-conditions, in which one thing is not entirely distinct from another, are seen not as something in themselves but as failed or incomplete versions of something else and better. Ignorance is not bliss; it’s a missed opportunity.

‘Voluptuous as the first approach of sleep,’ were the words Byron used to describe one evening twilight. It is a phrase which, with clean-edged condescension, would be considered sentimental now. But what about twilight, dusk and the burnt-out ends of smoky days, as the times in which most understanding is to be had? What about the virtues of ambiguity and the incomparable beauty of a lit sky over a dark earth? Isn’t it reflected, and not direct, light that illuminates the mind?

These were all troubling thoughts for me when I was considering the idea of making a long, deep investigation of the Shiants’ history. Would all the business of finding out destroy the islands’ enveloping magic? Would as much be lost in finding out as was gained? I spent a few days there trying to think it through. Only at the end of the last day did I decide. The blue evening was creeping over from the west. ‘Already night in his fold was gathering / A great flock of vagabond stars …’ And the answer was this: once the questions had arisen in my mind, it would be purely sentimental not to attempt to answer them. For many years I had walked across these islands without a question in my head. I had noticed, of course, the ruins here and there, the short stretches of wall, the cultivation ridges, the lazybeds, on whose ribs the forget-me-nots and meadowsweet grew, with the yellow flags and watermint in the ditches between them. They all had remained, so to speak, in a dusky condition, contentedly ambiguous, a sign of the undifferentiated past.

That had changed now. I had changed. I wanted to know. I wanted to bring this ambiguous sub-conscious of the place up to the level of full consciousness. Why? Perhaps because I felt more social about the islands. In my twenties, they had been somewhere to escape from a fretful marriage and from a fretful job in a publishers’ office. They were cut away from the adult world, somewhere a kind of ideal and delayed boyhood could be lived out for a few weeks. Isolation was integral to that. This was a place where I was happy to be alone. The idea of investigating earlier lives, and all the team work that would have involved, would have been an interruption to the pleasures and safety of solitude.

That is what has changed and this book is evidence of it. I have known the ecstasy of being alone here but at least partly I have left that behind. It was fuelled by a feeling that the presence of other people could only be damaging and that islands at least allowed the solitary self to exist without apology. I don’t feel that any more. Solitariness now seems to me a diminished rather than a heightened state. It is one way of being alive, with its own rewards, but it is not necessarily the best way and, besides, solitude can only mean anything in counterpoint to sociability. Now I want to people these islands, both in reality, and in that deeper sense, to discover what life the Shiants might have nurtured over the years.

I left with my mind made up. In the University Library at Cambridge I found a series of volumes published by various archaeological expeditions to the Hebrides. One in particular drew my eye. It described the discovery of a Neolithic house, lying just under the floor surface of a late-eighteenth-century house in the obscure valley of a stream called Allt Chrisal in Barra. The excavations had summoned an exact and ancient past, full of ghostly suggestions of hearths and sleeping places, potsherds and flint tools, from a landscape which all others had looked at with scarcely a second thought. Its authors were Keith Branigan and Patrick Foster, from Sheffield University. I rang Branigan. He was too busy and put me on to Foster, now attached to the State Institute of Archaeology in Prague. I rang him there. Would he leave his Hallstatt burials and Neolithic riverside timber halls for a while and come to the stony exigencies of the Shiants? He jumped at it. His Hebridean programme had come to an end. He had been longing to return. When could he come?

Pat is a remarkable man and gifted archaeologist, of enormous, cheerful enthusiasm and a wide variety of experience, (son of a Northamptonshire stonemason, gunner in the Royal Artillery, stationed for two years on St Kilda, mature PhD student at Sheffield University, studying the reuse of Roman building stone in Saxon churches, tyre salesman, collector of postcards, guns from the Wild West and a variety of mementos of the British Empire).

He is passionate, physically strong, full of unstoppable energy and with a commitment to the field realities of archaeology, to getting your hands dirty. He arrived one afternoon on Malcolm Macleod’s boat from Stornoway. I went out to meet him and as he stepped down into the dinghy, he was rubbing his hands like a hungry man about to sit down to dinner. I gave him a cup of tea in the house and he began surveying the territory. From morning till night, he walked up and down the islands. You would see him from time to time on the skyline, or peering down at some tumbled stones, or just occasionally, in the lee of an old wall, catching a few minutes sleep in the sunshine. I came with him as much as I could and we walked across the islands together, for many hours, arguing, suggesting, attempting to find coherence in the evidence he was turning up.

The places in which people have lived here are not scattered at random across the islands like confetti after a wedding. Just as the puffins cluster in some spots particularly suited to them – ground good for burrowing, steep enough for easy take-off – guillemots and razorbills in others – room for communal clustering on convenient shelves, access to fishing grounds – people over the millennia have used what the landscape has given them.

As the days went by, I took Pat to the different parts of the islands where I thought people must have lived. We treated the Shiants like prospectors, newly arrived in a new world. What would we make of this? What kind of life could we sustain here? The first place, of course, was around the modern house on Eilean an Tighe. Down there on the coastal shelf is where anyone would choose: near a landing beach and and within a minute or two of both west and east coasts, lots of sweet water in the small seeps at the cliff foot, mounds of seaweed from the bay on the west coast, good growing ground, easy, level, relatively rich, convenient. It is not surprising that the modern house and other early and recent buildings are here. It is where, when I am here with my family, we spend most of our time, moving between boats and shore and well and house, digging over the vegetable garden, cooking sometimes on the flat rocks beside the ruins. It is the most obvious place for a Shiant home. As a result, there is little that is identifiable as prehistoric on the ground. Pat was convinced, though, that it was certain to be there, buried under later structures. Any investigation would have to wait.

A thin, old path leads from that house settlement up into the middle valley of Eilean an Tighe, skirting the upper edge of the cultivation ridges, running between them and the steep screes above. The path is as wriggly as a thread fallen on carpet and after a climb of a hundred and fifty feet or so it emerges on to the wide, level plateau of the central valley. Here there is a second cluster of buildings. They do not seem older than the seventeenth or eighteenth century, but with good corn ground here (now undrained and so boggy) and sweet running water, it is nearly inconceivable that these later buildings do not overlie much earlier structures. They are not near the shore, but are within fifteen minutes’ walk of the landing beach. This, too, hidden beneath the early modern ruins and the rushes and flag irises that have grown up around them, is another place of ancient habitation. It is the site, as I shall describe later, of the house we excavated.

This was a strange experience for me. Places in which I had only ever walked and looked before were now subject to analysis and investigation. Everywhere we came to I could remember playing football with my children, or lying in the shelter of the walls away from the wind on a sunny day, or going there in the middle of a summer night, with the starlight dropping around us and the snipe fluting in the marsh. I had never, curiously, considered much beyond an idle thought what had happened there before. So this was an intriguing and rattling experience: the archaeologist and the psychoanalyst are close cousins.

Then I took Pat over to Garbh Eilean, dragging him up the steep southern face, Sron Lionta, and over to what has always been to me one of the most lovely places on the Shiants, tucked into the south-west coast of the island. It is called Annat, a name whose resonances I will explore later. A stream comes down to the shore there, dropping from one peaty, basin-sized pool to another, running between little meadows and then tumbling over the black rocks into a deep, seaweed-lined pool, where on calm days a boat can be brought in as if next to a quay, and where you can swim with twelve feet of water below you, glass-clear to the red of the dulse and the fretted lionskin of the wrack, while the fresh, cold moorland water drops through a beard of green weed on to your head. There is ruin after ruin here, one laid on top of another. The soil is not particularly rich, although it is not as sour as the moor above and has obviously been improved. A huge, round stone platform, perhaps a hundred feet across and up to eight feet deep, has been built here next to the place where the stream falls into the sea. Pat thought that it might well be the foundations of a large Neolithic house. There are vestiges of other buildings, including what might be a small, round Bronze Age house, and a large, mysterious D-shaped enclosure, perhaps for animals. In the nineteenth century, shepherds built a fank here, a sheep-gathering pen, using the stone they found on the surface, and little of what had been there before is now obvious.

Annat, too, awaits its excavation. It may well turn out to be the richest place of all the places on the Shiants.

Up from there, over the heights of Garbh Eilean and down at the far north-eastern corner to the place now known as the Bagh, the Gaelic for ‘Bay’. It was like showing Pat my treasures, opening box after box. Here, around the lush and bright green slopes there is another set of tumbled and ruined buildings. This, too, feels like a favoured place: the best shelter from the southwesterlies in any part of the islands, in under the lee of the big north cliffs; a supply of fresh water seeping from the rocks, which I have never known run dry; luscious red and pink campions grown from the turfy cushions; highly productive land on the underlying band of Jurassic rocks, some of the best soils not only in the Shiants but in the whole stretch of the Outer Hebrides from the Sound of Harris to Stornoway; a convenient landing place in the bay below; plenty of easily harvested seaweed to enrich the soils; and the enormous quantities of sea birds which nest in the surrounding screes and grassy slopes, in their hundreds of thousands.

One of the miracles of the Shiants is that a place like this, no more than a few acres, and no more than a mile from the modern house and the landing beach, feels as if it is in a different world. Perhaps because of its shelter from the wind, perhaps because of the sweetness of the turf in which the daisies grow like on a southern lawn; perhaps because of the way the puffins wheel across this corner, their shadows cast onto the grass like the revolving patterns of light and dark on a Fifties dance floor; perhaps because from here the Shiants are spread out before you to make an auditorium, cupping the bay of the islands in their arms; perhaps because from here there are such wonderful views across the Stream of the Blue Men to the long, tweed-coloured coast of Pairc, blue in its prominences, black and brown in the depths of its crevices, so near on a bright day you think you could touch Kebock Head; perhaps because a long habit of occupation is so obvious here, this, I think, is where I would have lived.

It is not surprising that here, among the more ambiguous heaps of stone – fowling shelters, summer huts or shielings from the nineteenth century, whose corner cupboards raised above the earth floors were intended to keep the dairy products cool – is something which seems to emerge from an extraordinarily distant past. Like almost every other structure noticed by Pat, no one had seen it before. Some way up from the beach, settled into the grassy slope below the cliffs, a few yards away from the edge of the enormous screes into which the tumbled blocks of columnar dolerite have collapsed, are a pair of rock shelters.

A many-tonned lump of rock, about ten feet across, has fallen so that its two edges rest on other rocks, leaving an irregular hollow beneath it, six or eight feet across and about four feet high. Its floor is very crudely but quite unmistakably paved with small, flattish slabs. Where the boulders do not quite make a neat seal around the place they enclose, small lengths of dry-stone walling have been built to fill in the gaps. Inside the shelter, structures which look like stone shelving have been built. Although it is a little sheepy now, and there are rats that run in and out of the place, it is not at all difficult when you crawl in there to imagine this as a kind of home. It is a tent made of boulders. As my son Ben said to me, it is the sort of shed Fred Flintstone might have built.

There is another slightly smaller one just downhill from the first and alongside them, where the sheep have kicked open the turf, limpet shells and pieces of crude, undatable pottery tumble down the slope: the midden, the rubbish heap, of those who used the shelters. It is not possible to date them yet. Extremely careful, microsurgical excavation might do that in the future and all Pat Foster will currently say, once again, is the careful non-commitment of the archaeologist: ‘multi-period’.

We went over to Eilean Mhuire, but here the mystery remains as profound as it has ever been. Most of its upper surface is made up of the soft Jurassic rocks which are also to be found at the Bagh on Garbh Eilean. The rocks have meant that nowhere on the Shiants is more luscious than these soft, easy slopes. It is salutary to remember that almost the entire history of the Shiants would have been shoeless. Even in the early twentieth century on Lewis there were families living without shoes. That understanding transforms your idea of the way in which people lived here, their canny, prehensile toes, gripping the rocks with an assurance and a fittedness which we have now lost. And after climbing up from the beach on Mary, a stiff, crumbly climb on a narrow path through the igneous rocks that underlie the sedimentaries of the upper surface, you can feel today, if you do this shoeless, the beautiful relief of arriving at Mary’s luxuriant pastures. This is the island of fertility and welcome. It is all too easy to imagine these Atlantic islands, as Yeats said of the Arans, as places ‘where men must reap with knives because of the stones’. That is not true on Eilean Mhuire. It would always have been the Shiant islanders’ granary. It was their garden island and the sheep that graze here are still the fattest that either the Shiants or anywhere else in Lewis can produce. It is and always has been good land.

Did people live on Eilean Mhuire in prehistory? That question cannot yet be answered. There are the remains of seventeen houses here, two or three of them making mounds that stand seven feet above the surrounding land.

Such an accumulation of material surely indicates long occupation. But there is a difficulty. Because the Jurassic rocks crumble so easily there is almost no building stone on the upper surface of the island. These house remains are made of turf, which has itself broken down to soil. There is, in other words, no hard structure which archaeology can interrogate. So how old are these buildings? How many of them were in use at the same time? Were they permanent or temporary habitations? Certainly this is the richest place in the islands, but it is also one of the windiest, and its water supply, from a deep, rushy hollow on the southern side, is not entirely reliable. Would people have lived here if they could have chosen to live at the Bay or at Annat or at either of the spots on Eilean an Tighe? Probably not. Eilean Mhuire would have been of central importance for the Shiant Islanders’ food supply but would not have been a favoured place to live, particularly in the winter, when gales from all quarters would sweep across it.

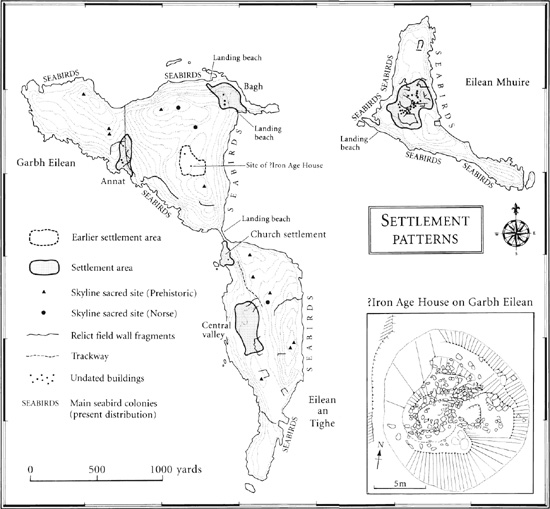

These were the five places in which people would have lived on the Shiants, at least in the last few centuries: two on Eilean an Tighe, two on Garbh Eilean and one on Eilean Mhuire. Pat found one other cluster of what looked like prehistoric houses. It was the most intriguing. On the high ground of Garbh Eilean, some four hundred and fifty feet above sea-level, in an area which is now no more than acid peat bog (with the marks of some nineteenth-century peat cutting still visible in it) are one or two rushy pools and sour, reddish moor grasses. This is the area now occupied most densely by the great skuas. They have only been there since the mid-1980s, spreading south from their breeding grounds in the northern isles. In early summer, when defending their young, they are terrifying birds, an imperial presence on the heights of the island, carefully shadowing your arrival on their ground, making an admonitory ‘kark’ at first from a distance, sometimes accompanied by a beautiful, high-winged display, as two birds fly one above the other, both with their wings lifted in a steep-sided V of victory and viciousness. If you persist with your trespass, the skuas come for you, flying as adroitly as hunter-fighters in a mountainous battle zone, concealing themselves behind the natural mounding of the island until the last minute, when they emerge, feet from your head, with a rushing of air in wings. I have never been hit but Kennie Mackenzie, John Murdo Matheson’s uncle, knew a man who had his scalp split open by a passing skua. ‘It was the shock more than anything,’ Kennie said.

Here, in their territory, are several stony mounds which are likely to conceal some form of prehistoric habitation. Many of them, all now visible from hundreds of yards away because their better drainage and the enrichment of the soil allows sweeter, greener grasses to grow there, had summer huts or shielings built on top of them in the nineteenth century. And that is where the skuas make their surveying stands. It is a Hebridean stratigraphy: possible Bronze or Iron age houses, nineteenth-century shielings in which the girls and boys would stay in the summer, tending to the cattle, making the cheese and butter, and above them the skuas, Viking birds, heroic, bitter northern, aggressive, magnificent modern invaders. Bits and pieces of puffin and kittiwake litter their nests.

No one of course would think of living up there now. The conditions would be intolerable and there would be nothing to draw you there. You could grow nothing in those waterlogged soils. But if you wanted a demonstration of the deterioration in the climate, this is it. What is now peat bog might, in the Bronze Age, have been freshwater pools. What is now sour moorland through which the sheep pick to find their sustenance might then have been arable fields. On Lewis itself, near the stone circles at Callanish, archaeologists from Edinburgh University have cut through the peat, sometimes five or six feet deep, to find Neolithic fields, complete with stone walls, houses and the marks of primitive ploughs lying underneath, exactly as they were abandoned, the people retreating through the thickening of the rain and wind. Up here are the remains of what may well be ancient habitations and, under the ruin of a nineteenth-century summer shieling, the remains of the largest structure ever built on the Shiants. It is an Iron Age house, sitting on a mound or platform fifty feet across and six feet high. The house itself is perhaps thirty feet in diameter, able to accommodate perhaps as many as fifteen people, and with clear marks of radial dividing walls still poking out between the nettles. That too awaits excavation.

Apart from that ancient anomaly, high on Garbh Eilean, there is distinct pattern here. It seems that the Shiants – like many parts of upland Britain – divide into two sorts of landscape, which are inter-dependent and can broadly be defined as ‘core’ and ‘margin’. In the cores, you have arable ground, fresh water and easy access to the shore. In the margins you have rough grazing, bogs or stagnant pools and a great distance from boats and beaches. People build their houses and live permanently in the core areas. In the margins, they go in the summer, building shelters and temporary lean-tos, but little more.

Pat also discovered a fascinating extra dimension to this relationship of core to margin. Arranged on the skylines, as seen from these core settlement areas, are a succession of prehistoric ritual sites, deep in the sour and marginal country. On Eilean an Tighe, a series of Bronze Age cairns stand sentinel on the high ground to the east and south of the settled areas. On Garbh Eilean, there are other Bronze Age cairns on the heights, while, above the north-western cliffs of Stocanish, the Shiants’ own diminutive menhir, standing only eight inches high on a mound about four feet across, perhaps marks a Bronze Age grave.

As will emerge later, when the Norse arrived, they too seem to have made use of the dramatic skyline for their own burials.

Tentative, uncertain and provisional as it is, not making any firm distinctions between different periods of prehistory, a kind of answer emerges from the survey. The place was occupied in prehistory with evidence of Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age houses. The Shiants are a microcosm, if a slightly impoverished one, of the Hebrides as a whole. There are armies of ghosts here. One can make a guess at how many Shiant Islanders there have ever been. If each of the core areas could accommodate a family of, say, five people; if the islands were occupied from, say, 3000 BC until the mid-eighteenth century, a length of about four thousand, eight hundred years; and if people lived on average until they were thirty, that would give you about three and a half thousand people who would have known the Shiants as home. This is not an empty rock; it is soaked in memory. At the moment little more than that can be said.

My question remains nearly unanswered. Would the Shiants have been the sort of place in the Bronze Age to which an object such as the golden torc dredged up off the Galtas would naturally have belonged? Probably not. It is not rich enough. The island group is too small, too poor and too difficult to access for any great or rich man ever to have made it his headquarters. In prehistory, as ever, the Shiants were in the shadow of the bulk of Lewis to the west. The torc, in other words, came from somewhere else.

Was it, then, somehow wafted here? Perhaps. Because the sea-bed in the Minch is extremely lumpy, the passage of anything across its floor would be difficult, but it is not inconceivable that a light metal object such as this might be drifted from one place to another. Stones of all sorts are to be found on the Shiant beaches. There are always one or two cobbles of black and white banded gneiss from Lewis to be found among the cool grey of the Shiant dolerites. Some of those will certainly have been dropped here by glaciers. There is a large lump of gneiss sitting on the turf at the eastern end of Eilean Mhuire, brought here by glacier from around Stornoway, twenty miles to the north. But other stones, red granites, green cupric metamorphics, even the occasional tiny natural flint nodule, all of which you find on the beach and all of whose origins can only have been to the south or east, could not have been brought here by the ice sheet, which was travelling in the other direction.

So the torc might have been washed here by the tide or by the slow underlying current which pushes slowly north, year in, year out, up the Minch. The existence of that current was only detected in the 1980s when the movement of radiocaesium from the Sellafield nuclear reprocessing plant on the west coast of Cumbria was tracked up the Minch and out into the North Atlantic. Thanks to the persistence of radiocaesium, that current, it is now known, moves at about two and a half miles a day, nine hundred miles a year. The torc has had three thousand years to get here – it is contemporary with Greeks laying siege to Troy. It had time enough to have come here from anywhere.

The simple wafting of the torc must remain a possibility, although perhaps an unlikely one. So did it, then, go down in a Bronze Age wreck? Divers and marine archaeologists have asked Donald MacSween exactly where he found the torc. He will not say. Not that he can know precisely. On the trawl which picked it up, the scallop dredge had been down for several hours as the Favour followed its usual spiral path round and round the sea-bed. He has gone back himself but nothing else of the sort has yet emerged from the spot. But perhaps there is a Bronze Age wreck down there. Evidence is accumulating that the Bronze Age seas, while not exactly crowded with shipping, would not have been an utterly alien environment to man. Bronze Age boats have long been known from the Humber Estuary, where three have been dug out of the clay ooze. Their heavy oak planks were laced together with lashings made of yew, part of a sewn boat tradition that extends around northern Europe, through the Baltic and across the Kola peninsula to northern Russia.

The Humber boats were probably only used as ferries across the estuary but more relevant is a large sea-going Bronze Age boat, about forty foot long, found in Dover in 1992. The boat, which was about the same age as the torc, was partly pegged together and partly stitched with yew withies. The seams had been made watertight by squeezing moss between the huge oak planks. John MacAulay knew a man whose father was still doing the same in the Hebrides early in the twentieth century, the only difference being that he soaked the moss in Stockholm tar. The bottom of the Dover boat had clearly been run up again and again on stony shores and been grooved and scuffed in the process. And inside it the archaeologists found part of its ancient cargo, a piece of shale from Kimmeridge, a hundred and eighty miles away along the south coast of England.

No one has found any convincing evidence of a Bronze Age sail, at least outside the Mediterranean, but it seems likely that early journeys across the Minch would have been under sail. It was a case then, as now in Freyja, or any craft with vulnerabilities, of picking your day. Surely to the south of here, the large paddle-driven boat would have aimed to make a crossing, perhaps from Ireland, perhaps from Wales, both possible sources of the gold in the torc, to the Scottish or English shore. It would have felt good, as ever, when they set out. The boat would have seemed large and capable in the calm and the sunshine. People have surely always laughed at this moment, when the sea seems kind and the future a sequence of possibilities? Then the weather turns wrong, and the experience is one only of fear. The boat was surely driven north in the storm, rather than making its way here. For what could a man or woman who had in their possession such a torc want with this northern place? Perhaps for a day or two, they were driven before the wind. It is two hundred miles to the Shiants from Malin Head, the nearest point of Ireland. It would take a day and a night at five knots, suffering the cold of hell, baling hard as one roller after another came aboard, to cross that sea. Suddenly, out of the storm those bitter rocks would materialise, and the people would die as the surf threw them at the pinnacles. One piece of geometry is significant: Donald and Kenny found the torc on the southern side of the Galtas. That was the side from which the Bronze Age boat was slammed into them. Those rocks, a bar set by the Shiants, mark the northern limit beyond which the golden torcs of Celtic Europe never reached.

The experience of shipwreck would have been the same millennium after millennium and almost every one would have gone unrecorded. Only after the Merchant Shipping Act of 1854 were the Receivers of Wreck in every port around Britain obliged to make an Examination on Oath of the master of any ship that was lost in the waters for which they were responsible. Finally, in the last few decades before marine combustion engines changed for ever the relationship of man to the sea, the pitiable condition of ships in a storm are recorded.

There is an account taken down by the Stornoway Receiver in January 1876 which goes some way to re-enacting the loss of the Bronze Age boat. The Neda, a large, wooden barque, three hundred and seventy-four tons, registered at Newcastle, had as master Joseph Clark, a Newcastle man. His wife and child were on board and there were ten crew, including the Irish mate Patrick Brady, an illiterate. The Neda had been at Dublin and cast off from the docks at noon on 17 January, destined for Newcastle, the tide at half flood and the wind blowing a fresh breeze from the west. The intention had been to go by the Irish Sea and English Channel but because of the wind backing into the south-west, it was, as Brady told the Receiver ‘decided to go north about’.

All went well until they passed the light on Skerryvore, the shipwrecking rock, one of the richest of all British graveyards, standing ten miles out into the Atlantic south-west of Tiree. They had passed the light at nine o’clock on the morning of the 22nd, and soon afterwards ‘a heavy gale, accompanied by drizzling rain and a high sea sprang up’. Half-way through that afternoon, in steadily deteriorating conditions, the Master laid the ship to, under nothing but her reefed main topsail. The storm worsened and visibility sank. Constant watch was kept for any land. At three o’clock the following morning, land, somehow, was sighted and they stood in towards it. Only at six did the day lighten enough for them to recognise it as the south-west corner of Skye, dominated by the heights of the Cuillins. (That is the reason all mountains in the Hebrides have Norse names: they are the only seamarks in foul weather.)

Immediately, Clark put the Neda onto the other tack and headed for the western side of the Minch. About ten o’clock that morning, Sunday 23 January, they sighted an island to the north but it could not be identified, ‘the wind at the time rising in the SSW and blowing a gale and the weather very thick with rain.’ They had no idea where they were. For safety’s sake, he brought all the crew on deck and turned east again, away from the Harris shore. The wind had shifted a little, now south by west, and was shrieking in the rigging. Mrs Clark and their child were cowering below. Quite suddenly, ‘a quarter of a mile ahead, a little on the port bow’, the Shiants came at them, out of ‘the thick rain gale’. The ship was immediately ‘hauled to the wind and every effort made to escape the land’, as Brady told the Receiver of Wreck, ‘but this being found impossible Master ordered said ship to be run ashore on the largest of the Shiant Islands.’

I have often wondered exactly where the Neda struck. There is no easy place for which Clark could have aimed on that south-western shore of Eilean an Tighe. The whole extent of it is a series of craggy little inlets and intervening shards of rock. The reporter from the Oban Times had heard that the Shiant shepherd, Donald Campbell, was instrumental in saving the lives of all on board. He noticed the barque coming to a place where she would have been dashed to pieces and all lives lost, and from the shore he waved to those on board and guided them so that they were able to run the vessel ashore, clear of sunken rocks.

Wherever it was, it can have been no gentle landing. The huge seas driving in from the south-west picked her up and slammed her on to the rocks. Her masts collapsed forwards and the rudder was soon gone. The keel soon broke and the decks, as they always will in a ship whose whole frame and body is rupturing, began to ‘start’ – the planks springing away from their housing. The ship had gone ashore starboard side to, and the hull was soon stove in on that side in the bilges. The hull, which had been insured for £2,500, was later sold as a lump of partially salvageable timber, for £68 and its contents for £246.

All thirteen of the lives on board the Neda were saved. One of the crew swam ashore through the surf as soon as the ship struck, the other twelve remained on board until the tide fell and ‘were lowered over the said ship’s side on to the rocks by means of a rope and were afterwards sheltered in a shepherd’s cottage.’ As the Oban Times said, ‘To the shipwrecked crew – especially to the captain’s child, who was much injured – the shepherd and his wife showed every kindness and attention, and all speak highly of the efforts which this poor and lonely couple made for their comforts.’

On Friday 28 January 1876, the attention was drawn of a Harris boat out fishing on a still-wild Minch and the Master was taken to Stornoway. His wife, child and the rest of the crew stayed with the Campbells until the following Thursday, when the storm had abated.

The wreck of the Neda is still remembered in Harris. Uisdean MacSween once described to me the moments after the ship had gone ashore. He thought that the Campbells had been alerted by the single crewman who had swum through the surf. They hurried down to the western side of Mianish and stood open-mouthed at this sudden irruption into their lives. Once the tide had dropped, most of the crew were indeed happy to leave the splintered ship for the security of land, however windswept. But Mrs Clark, the Master’s wife, was not keen. Sheltering her child in her arms, she looked at the Shiant Islanders, monoglot Gaelic speakers, the men vast and hairy, with their beards, Hughie said, ‘reaching down to their waists’, drenched in the rain and wind, their hair plastered to their heads, their feet probably naked, and thought of her parlour in Wallsend, its polished iron range and cretonne furnishings. Mrs Clark screamed above the wind, ‘I’d rather stay here than put myself into the hands of men such as those!’ Her husband was having none of it. He ordered two of his crew to tie up his wife and have her carried ashore, in Hughie’s words, ‘like a bale of ticking’.

Without question, there would have been people living here when the Bronze Age torc somehow arrived off the Galtas. It is not inconceivable that the same kind of welcome might have been extended to them.

But there is another possibility. The torc may not have come to the Shiants from a wreck. It might have been deliberately dropped into the sea here. This is, perhaps, at the outer reaches of speculation, but it is not outlandish. There are arguments to be made, and precedents to be brought from elsewhere towards the end of the Middle Bronze Age, which suggest that this piece of gold may indeed have been deliberately thrown away.

The Bronze Age, beginning in Britain at the start of the second millennium BC, had marked a change in human consciousness. No longer the giant communal monuments, the New Granges and the Stonehenges, nor the communal graves in which individual bodies were dismembered and all parts of all people scattered together. In one of the neolithic tombs of the Orkneys, at Isbister, the remains of the people were mixed with the bones of another animal: at least eight and maybe ten white-tailed sea eagles were also buried there. This may be chance; the eagles may have used the tomb as a cave-like eyrie. But it has also been suggested, more intriguingly, that it is the eagles whose grave this is, a place which the human beings were allowed to share as a privilege. At the time, with the average height of men no more than five feet, six inches, and the average life expectancy in the mid-twenties, the eagles would have been both larger and longer lived than almost every person. The human bodies may even have been exposed at death for the sea eagles to consume as their royal food.

That frame of mind, a certain Neolithic humility, disappears in the Bronze Age. The hero arrives. Agamemnon and Achilles are the Bronze Age archetypes and hubris becomes their governing sin. The human person is glorified and with his egotism comes his guilt. He carries remarkable weapons. He wears jewellery. His body becomes the arena of his glory. Bronze itself requires travel, exchange and communication because tin and copper are only rarely found together in nature. The idea of the exotic – amber from the Baltic, faience beads from the eastern Mediterranean, silver from Bohemia – becomes the individual’s mark of splendour. In the Bronze Age, with his marvellous things alongside him, the individual man is buried alone.

Metal was the means for this glorification of the person. Its emergence from rock to burnished strength was itself marvellous and that transformational quality, that birth of the precious from the dross, was symbolic of potency and magic. This material was not for use but for beauty. It was a jewellery culture. The standing of important people was bound up with it. The tiny socketed bronze axe heads that have been found in Scotland, the symbolic spears and shields, too thin to be used in battle but as perfect in their making as the breastplates now worn by the Household Cavalry, or those tiny medallion hints at a breastplate which officers wore throughout the nineteenth century, a hint of manhood in the candlelit halls: this is an understanding of metal not in the huge material sense of the Victorian engineer, but in the amazed and delighted vision of the jeweller. That is why this torc is more important than it seems. It does not matter because it is pretty. It matters because in its incorruptibility and rustlessness, the very qualities which drew Kenny Cunningham to its value, it is a denial of death, a sketch of perfection and eternity.

Conditions started to decline towards the end of the second millennium BC. The weather worsened. The land which had been taken in for agriculture throughout this Atlantic fringe of Europe started to become difficult. And in difficulty, life became violent and frightened. The amount of metal, whether bronze or gold, that was in circulation on the European web of connections, along the river valleys and the western seaways, began to decline. But this was no democracy. There was no trimming of the top end to help the people at the bottom. Far from it. The number of pieces whose purpose was elegance and display actually increased. Beautiful shields, large cauldrons made out of sheet bronze, gold torcs: as the weather thickened and the crops diminished, more and more of these nearly useless objects were made. Social stress produced not an arms race but a beauty contest.

Slowly, one needs to approach the idea of the gold torc being thrown into the sea off the Galtas. And to do that one needs to understand the idea of the gift. It remains true that the giver of a gift exerts power over its recipient. The recipient remains in debt to his benefactor. And he can only absolve himself of that debt by giving in return. This leads without much interval to a generosity contest. Give and you shall ordain. Give back and you shall conquer. In pre-capitalist societies, it is not the accumulation of wealth which is the mark of standing but the ability to dispose of it in the form of gifts.

Consider for a moment that the torc might be a gift to the world. If it had been thrown into the Minch, it would be, as Trevor Cowie, its curator in the National Museums of Scotland, has written, ‘a means of accumulating prestige without the risk of the original gift being returned or “trumped” with the loss of status that would ensue.’ If you can give something of such enormous value to the Minch, the Minch will be forever in your debt. Such gifts to the world are found all over Europe in the Bronze Age and later. The hoards, which earlier generations of archaeologists interpreted either as the hurried concealment of treasured goods or the nest eggs of travelling merchants who failed for some reason to collect them, are now starting to be seen in this different light.

The golden torcs are often found with other precious objects. The one in the fen at Stretham in Cambridgeshire had with it a golden bracelet, some rings and human bones, although that is exceptional. Another in the Fens was accompanied by some bronze adze-axes called palstaves. The one in Calvados had with it a bracelet, a spear, a razor, a small anvil and a hammer for working the metal. In Lewis, such a hoard was found in 1910 at Adabrock, in Ness, just beyond the Shiants’ northern horizon. Bronze axes, a gouge, a spearhead, a hammer, three razors, two whetstones and some beads, one of glass, two of amber and one of beaten gold, were recovered from under three yards of peat. The Bronze Age acts with unparalleled generosity to the earth as the earth grows meaner.

The Shiant torc fits. It is on the very margins of the Europe in which these practices occur. The place in which it was found is as dramatic as landscape comes. Intriguingly, another torc, similar to this one in its tapered terminals but without the twisted decoration, was found at the Giant’s Causeway in Antrim, the columnar dolerite sill whose structure so closely resembles the geology of the Shiants. That is perhaps no more than a coincidence, but it is a suggestive one: the brightness of the gold against the dark near-architecture of the columned rock, a bringing together of opposites which once seen would not be forgotten. The Shiants are also the most northerly example of this sort of rock. Is it a coincidence that the most northerly golden torc was found at this most northerly extension of the British volcanic landscape? Was there a Bronze Age recognition that the Shiants marked a sort of frontier? Certainly no rock is more easily identified by a non-geologist than columnar dolerite. It continues to have the air of divine or diabolical sculpture. And the Norse may have recognised this too. Another possible derivation for the name is Galt, the Old Norse word for ‘magic’ or ‘charm’.

The northern boundary of their world would have been important to the middle and late Bronze Age. As the weather worsened, it would have been seen to have been coming from the north. Looking from the south, was this, I wonder, the outer margin of the world as it was known, the frontier between what was theirs and what they feared and needed to resist and control? The Galtas, the most sculptural of all the columnar formations in the Shiants, are like a giant’s causeway that has been set adrift, afloat on the tide. As Thomas O’Farrell, the Ordnance Survey man, saw in 1851, the tide run is savage between them ‘at all times especially at Spring tides there is a rapid current. About them the tide flows exceedingly strong, flowing the same as a large River.’

The gift of the torc here – and perhaps of other objects which have yet to be found – was an act not of propitiation but of dominance. The Bronze Age chieftain gave away what was most precious to him and in doing that showed his standing in the world and his control over its nature. The Shiants marked the frontier of that golden world and the throwing of the torc into the teeth of the Galtas was an act of symbolic empire.

I have often taken boats through there. You need a quiet day but, however quiet the weather, the sea still bumps and ripples around you. Small spiralling eddies break off from the corners of the stacks and for a few seconds adopt a life of their own. Little insucking constellations of bubbled water waltz and veer across the liquid floor. Sometimes there is a succession of them, a troupe of whirling water-dancers strung out before you, making their way from rock to rock, formation-dancing in the tide. The hull tips with the turbulence as you squeeze past them. Some of the channels are no more than ten or twelve feet wide, and as deep as that, square beams of running water below you, as wonderful as liquid steel for their concentration of energies. It is a place which can never be the same however often you return and I have gone back there for year after year. If there is any kind of swell you have to be careful with the boat, holding it back on the surge, pushing it forward as the swell sucks away again, choosing the moment to be swept on through, suddenly leaving the Galtas behind, out again in the widths of the Minch. Occasionally in a corner between the rocks you can find a still backwater pool where the boat can rest and slowly turn and you can watch, beside you, the long fronds of the kelp billowing in the channels like hair. Underwater, it is a swept world. No sediment, but a place of endless movement, recognised as magical three thousand years ago, still magical today.