8

ISLANDS FEED AN APPETITE for the absolute. They are removed from the human world, from its business and noise. Whatever the reality, a kind of silence seems to hang about them. It is not silence, because the sea beats on the shores and the birds scream and flutter above you. But it is a virtual silence, an absence of communication which reduces the islander to a naked condition in front of the universe. He is not padded by the conversation of others. Do you want the padding or do you feel shut in and de-natured by it? Do you love the nakedness, or do you shiver in the wind? Do you feel deprived by your island condition or somehow enabled and enriched by it?

Those are the questions for the solitary, now or at any time. Nothing is as envelopingly total as aloneness in a place like this but the silence, paradoxically enough, is far from empty. Whenever I have been alone on the Shiants, it has been a continuously social experience. If I am scrubbing the floor of the house, or out in the boat trying to catch some pollack or cod for my supper, or taking water from the well, or trying to make sense of the perplexing fragments from the past which litter the ground like the remains of a party no one has bothered to clear up, the whole time, in my mind, I am discussing with people I know everything that is going on around me. Isn’t it frustrating, I say to them, how when you wipe lino, you can never get it clean? Isn’t that wonderful how the water boatman sits within the meniscus of the well head pool? Do you see how that surface bows down to the pads of his feet? Think in the past how people must always have sat here in their boats, just at this point, hauling out the coleys where the flood tide rips on the unseen reef. Do you think the wind might be getting up? Is the darkness of that cloud a signal of the gale tonight? Is the mooring safe? Will the boat survive the storm? What, in the end, am I doing here?

All the solitaries of the past have lived with that intense inner sociability. Their minds are peopled with taunters, seducers, advisers, supervisors, friends and companions. It is one of the tests of being alone: a crowd from whom there is no hiding. It is tempting in these circumstances to turn Crusoe in the face of loneliness. A hermit will force himself to confront that crowd of critics. The followers of the great St Antony, the third-century founder of Christian monasticism, who immured himself for twenty years in the ruins of a Roman fort in the Egyptian desert, could hear him groaning and weeping as the demons tested him one by one. Defoe’s hero does the very opposite. He is endlessly busy, endlessly adapting the world as he finds it, building new shelters or planting new crops or finding new aspects to his island. He fills his solitude with business. He constructs boats and digs canals. I have spent weeks on the Shiants like that, making enough noise in working on, mending and setting creels, repairing fences, digging a vegetable patch in one of the old lazybeds, setting up winches on the beach, putting wire netting on the chimneypots to keep the rats from scampering down them, painting the house inside and out – all this, in the end, to keep the silence away.

Always at the back of that hurry is the knowledge that it is a screen against honesty. More than on anything else, Crusoe expended his energy on fences. He built huge palisades around both his island houses, the stakes driven into the ground, sharpened at the top, reinforced, stabilised, all designed to keep the world out. It was not the world he was fencing out but his own profoundly subversive and alarming sense of isolation.

That crowd of critics is the reason that even now, in the Orthodox church, which is the most direct descendant of the universal church of the seventh and eighth centuries, the life of the solitary is seen as the higher calling. A monk needs to qualify to become a hermit, through years of discipline and training, and of social acceptance within the monastic community. The hermitage, in other words, is only ever occupied by a profoundly cultured mind.

That is the first step towards understanding the man who lived in the Shiants a millennium ago and who made the stone. The hermit is no primitive. He may be primitivist – in his engagement with essentials, in his exposure to extreme honesty – but primitivism is one of the more sophisticated forms which civilisation can take. One needs to leave behind a great deal of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century thinking about these early churchmen. Gibbon thought monks as a whole a ‘race of filthy animals, to whom [one] is tempted to refuse the name of men.’ Compared with the elegance of Roman paganism, Christianity, with its filth and self-abasement, its adoration of nauseous relics and its elevation of the criminal to the holy was, Gibbon thought, a descent into barbarism.

In the summer of 1841, a reader of Gibbon, or of his followers, dropped anchor at the Shiants. James Wilson, Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh, Member of the Watercolour Society, was cruising the Hebrides as the future author of A Voyage around the Coasts of Scotland and the Isles:

On Eilan-na-Killy (the Island of the Cell) are the remains of some ancient habitation, the supposed dwelling of an ascetic monk, or ‘self-secluded man’ possibly a sulky, selfish, egotistical fellow, who could not accommodate himself to the customs of his fellow creatures. Such beings do very well to write sonnets about, now that they are (as we sincerely trust) all dead and buried, but the reader may depend upon it they were a vile pack, if we may apply the term to those who were too unamiable to be ever seen in congregation.

The Enlightenment saw only the vulgarities of asceticism, the disgustingness of existing, for example, on the Eucharist alone, or limiting oneself to a daily ration of a single fig, or even one small piece of dry bread every other day. A fourth-century Egyptian called Evagrius lived in a cell, in isolation for fifteen years, ‘eating only a pound of bread and a pint of oil in the space of three months.’

The Syrians, as Gibbon delightedly described, went further. Chains were worn around the neck and loins, often hidden beneath a hair shirt or a tunic made of wild animal skins. Others had themselves suspended from ropes so that they could never lie down or sleep in comfort. Some endlessly reopened wounds in their bodies or shut themselves in skin sacks, with an opening only for the nose and mouth. Still others lived as beggars, prostitutes or transvestites in the cities of the eastern empire, as holy fools, or famously on the top of columns for decades at a time.

These practices would almost certainly have been known to the Shiant hermit whose stone we found. The example of the early monks and hermits, through the hagiographies and collections of sayings which were held in the large library at Iona and other monasteries, would have been constantly in his mind. But it is scarcely the whole picture. The marginalised brutalism of the extreme Syrian ascetics, which held an almost pornographic fascination for Enlightenment rationalists, was not part of the mainstream monastic tradition. Even in Egypt, the wearing of chains, perpetual wandering, or living exposed to the elements without a cell, were disapproved of.

If I think of the hermit who lived on the Shiants, a more humane picture comes to mind. The world from which he emerged was profoundly literate. Most of the monks of whom there is any knowledge were highly educated and usually members of the ruling princely families of Ireland. Much of the standing which they enjoyed, and of the fame which allowed the reputation of the Shiant hermit to last more than a millennium, derived from the fact that they were great people in the world, who had voluntarily submitted themselves to the condition of exile and permanent pilgrimage. Martyrdom was only significant for those who could have chosen an easier path.

The idea of ‘a desert place in the ocean’, which emerged in Ireland in the sixth century, was fundamentally metropolitan. It is an outgrowth, in the end, of the urban civilisation of Europe and the Near East. No indigenous inhabitant of the Shiants would conceive of the islands in that way. Only a man who knew of the power of cities and the glories of courts would think of them like that. The hermit’s presence here is a reaching out of that Roman idea into the margins of the Atlantic. And there is something theatrical about it, self-dramatising. The turbulence of the seas, the visual violence of the cliffs, the way in which the islands stand out so tall on the horizon, ‘three lofty and desolate ones’ as the young naturalist George Clayton Atkinson described them in the 1830s – all of that makes the Shiants a setting for metaphysical drama.

It was a canny choice, for underneath the surface imagery, there is plenty here that can sustain life, that can ensure the hermit was not going to starve. No hermit chose the near-sterility of, say, Scalpay, which has neither the same visual drama nor the Shiants’ richness. Throughout the Hebrides the same pattern emerges: the relics of early Christianity tend to be on the best remote places. They ignore the acid ordinariness of Harris and Lewis and choose instead the fertility of Canna with its Columban sites, Berneray and Pabbay by Barra, the beautiful, easily worked machair of Barra itself and the Uists, Boreray, the other Berneray and Pabbay near Harris, the ecstatic beauties of Taransay, the huge wealth of birds on St Kilda and the Flannans, the Shiants and the rich fertility of North Rona, forty miles out in the Atlantic, north of the Butt of Lewis. Richness in extremis: the definition of the Celtic church.

Highly cultured, attuned to the meanings of the landscape, astute, and not, it emerges, radically alone. The Hebridean hermits, much like their models in the Near East, were in touch with each other and with the network of Columban monasteries here and in Ireland. Iona, in particular, was a centre of learning and spiritual civilisation. Greek was known and probably read there. A yearly chronicle was kept. Abbot Adomnan wrote a famous guide to the places of the Holy Land. At Iona, the abbot employed a baker, a butler and gardener. The abbey had lay tenants on the island. The governing spirit of Columba, an Irish prince, while majestic in its power over many centuries, and in the foundation of a holy austerity, was also pastoral, affectionate, social and generous. As they had done in the Egyptian desert, monks and hermits visited and cared for each other. Here, as there, the hermits were never truly independent. All were at least spiritually, if not physically, living with an elder. In the Hebrides that spiritual father, who had proved himself in the discipline by spending many years in solitude, fasting, praying and meditating, would have been the abbot of Iona or perhaps of Applecross on the mainland. As Thomas Owen Clancy has written, ‘Even among the early Desert Fathers who valued solitude and were called to “flee women and bishops”, there are countless tales told of the futility of a monk seeking mystical union with God if he is not merciful and attentive to his brother.’

Not that the island life was for everyone. There is the revealing story of Declan, a fifth-century Irish Saint, who with God’s advice and guidance had decided to settle on a remote western island called Ard Mor. He and his small band of disciples arrived at the beach opposite the island and found that all the boats had been stolen by the local people. The monks were frightened and told Declan that they would prefer to go elsewhere. They had to travel back and forth to the mainland if they were going to survive and that was not going to be helped by the hostility of the local people. When Declan died, as he surely would, and was no longer there to protect them in person, the situation would be even worse. They made an urgent appeal to the saint:

We implore you with heart and voice to leave that island, or to ask the Father in the name of the son through unity with the Holy Spirit … that this channel should be thrust out of its place in the sea, and in its place before your settlement should be level ground. Anyway, the place cannot be well or easily inhabited because of that channel. Therefore there cannot be a settlement there; on the contrary there could scarcely be a church there.

Declan was angry and told the monks that God alone would know whether or not Ard Mor could support a community. They all prayed and Declan struck the ground with his staff. The waters duly receded. Ard Mor had become a beautiful, habitable and accessible peninsula.

Remote islands, even then, were for extremists. If one has to abandon the picture of the early hermits as a set of filthy tramps, one must also get rid of the idea that they were somehow ecosolitaries a thousand years ahead of their time. The motivation of the hermits (the word derives from the Greek for a ‘desert’ – ereme) was the very opposite of the modern. Nothing resembling a Romantic desire to come close to nature and to see in that closeness a form of salvation can be found anywhere in the seventh or eighth centuries. The extreme and difficult desert of the Shiants (and the Latin desert or disert was the word used by the Irish churchmen for places such as this) was attractive in the seventh century precisely because of its horrors. Almost certainly, at this period, the Shiants were part of the territory controlled not by the Irish but by the Picts. Any hermit coming here (or for that matter to St Kilda, the Flannans or North Rona) had put himself far out into dangerous territory.

The sea itself terrified them. It was the zone not of divine beauty but of destruction and chaos. Only God and the saints could control it. Others were at its mercy. In the opening prayer of an Irish Mass written in about 800, the sea is the testing ground where God alone can save the pitiable: ‘We have sinned Lord, we have sinned. Spare us sinners and save us: You who guided Noah across the waters of the flood, hear us: and who by a word rescued Jonah from the deep, free us; You who stretched out your hand to the sinking Peter, help us.’

The animal world was no better. One hermit, finding himself on an island which would now be thought of as a bird sanctuary, was unable to pray because of the noise the birds were making. Only with God’s help was he able to silence them and, in the blessed quiet, address himself to the Creator.

Suddenly you can see the hermit there. He stands on the shore. This island is the only garden he has but the garden is his and it is God’s gift for him to use. The first chapter of Genesis is quite explicit and these are verses that are still quoted in the Hebrides:

Have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.

And God said, Behold, I have given you every herb bearing seed, which is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree, in the which is the fruit of a tree yielding seed; to you it shall be for meat.

And to every beast of the earth, and to every fowl of the air, and to every thing that creepeth upon the earth, wherein there is life, I have given every green herb for meat: and it was so.

Life in the seventh- or eighth-century Hebrides was not and could not be conservationist. Anything less than full access to the fruits of the earth on these margins of viability would tip life over from survival to suicide. Again and again, conditions in which crops might normally grow could turn catastrophic. In 670 a snowfall blanketed the whole of Ireland and brought on a universal famine. Snow fell again in 760, 764 and 895 and hunger followed. In 858 a rain-drenched autumn destroyed the entire harvest. In 1012 terrible rains wrecked the standing crops and in the following spring farmers had to choose between planting their seed corn or eating it, leaving nothing for the following year.

On islands it would be worse. The biographer of the Irish Saint Berach told the story of how in one of these years of scarcity a farmer on an island decided that he had to leave his wife and child while he searched for food on the mainland. As he left, he told his wife to kill their new baby because they could not hope to feed it.

Of this entire thought-world, only the pillow stone, apparently, survives on the Shiants. Can the stone itself be interrogated? Can one read from the stone anything of the mind of its maker? Of course, in the cross itself, it carries the full burden of Christianity. It is the symbol of Christ’s death, resurrection and continuing presence. It also carries the faint echo of a Roman imperial memory. The ring, which on this stone, and in many Irish stones, either surrounds or intersects the cross, has its origins in the imagery of the laurel wreath. Early examples found in Germany show the ring around the cross carved with the laurel leaves that would surround the head of Caesar. The ringed cross, then, is an elision of empire and the martyred Christ, of the majesty of the father and the suffering of the son, of imperium and humility, of greatness descending to the condition of martyrdom.

More precisely than that, though, it symbolises both the suffering and ambition of the life of the hermit himself. It is an extraordinarily self-sufficient object. It needs no context or frame to achieve its effect and was surely intended to be portable, to be carried from one place to another, to do its work wherever it might be, much as I have driven it around Britain, and sailed it back and forth across the Minch. The stone is a manifestation of holiness carried into the desert. But it also embodies holiness found in the desert. The carving, so laboriously done, not by an expert, draws life and meaning out of the inert lifelessness of rock. It is, in that way, a model of the way in which a man, isolating himself in a stony place surrounded by the sea, arrives at a new understanding of divine power in the world. Like Christ’s passion on the cross itself, it is the emergence of spiritual life from bodily death. Its beauty is not in itself but in the transformation it represents.

It may, just, be possible to make that stone speak. By chance, two poems survive in manuscript, one copied out in the sixteenth century and now in the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the other a century later and now in the National Library in Dublin, which are almost certainly the work of a hermit living on a sea-battered island in the Hebrides in the seventh century. The name of the poet-hermit is Beccan mac Luigdech. He is a scholarly man, and an aristocrat, profoundly versed in the ways of Irish heroic poetry, a member of the same Irish family as Columba. Beccan is devoted to Columba’s memory, as his leader, his spiritual father and his saint. The poems are themselves a rare enough survival, but what makes them more extraordinary is that they are joined by a letter, addressed to him as ‘Beccanus solitarius’, Beccan the hermit. It was written in 632 or 633, by an Irish churchman on the subject of the dating of Easter, the controversy then dividing the Columban from the Roman church.

A richer and more subtle world than one inhabited by ‘sulky, selfish, egotistical fellows’ emerges from Beccan’s verses. His is a landscape and seascape of immense richness and passion and through him the full depth and power of Latin Christendom reaches up into these stormy waters. Beccan may have been on the Shiants, but it is by no means certain that he was. There is, in fact, a possibility that his hermitage was on the island of Rum, south of Skye, halfway between the Shiants and Iona. But if Beccan was not the hermit here (and his connection to Columba points more at Iona than at Applecross), he was exactly contemporary with the man who was, he would almost certainly have known him and would have inhabited the same world. This is, quite legitimately, the voice of the stone.

Looking southwards from his island fastness, Beccan, as translated here by Thomas Owen Clancy, surveys the holy kingdom that Columba has created. Seas surge through the poetry and Columba, or Colum Cille, the Dove of the Church, both ascetic scholar and courageous adventurer, as much prince of Connacht as saint, the light of the world gleaming with sanctity, triumphs over them:

He brings northward to meet the Lord a bright crowd of chancels –

Colum Cille, kirks for hundreds, widespread candle.

Connacht’s candle, Britain’s candle, splendid ruler;

in scores of curraghs with an army of wretches he crossed the long-haired sea.

He crossed the wave-strewn wild country, foam flecked, seal-filled, savage, bounding, seething, white-tipped, pleasing, dismal.

Fame with virtues, a good life, his: ship of treasure, sea of knowledge, Conal’s offspring, people’s counsellor.

Leafy oak-tree, soul’s protection, rock of safety, the sun of monks, mighty ruler, Colum Cille.

Age does not diminish this. As passionate as Emily Dickinson and as power-driven as the Anglo-Saxon sea poems, Beccan suddenly vivifies the seventh-century Shiants.

In his only other surviving poem, as Columba appears again, all elements of the hermit world are brought together. Sea-heroism, austerity, skill in extremis, persistence, the princeliness of Columba’s holy enterprise, the imitation of Christ and the love of learning rise together in a moment of heroic completeness:

He left Ireland, entered a pact,

he crossed in ships the whales’ shrine.

He shattered lusts – it shone on him –

a bold man over the sea’s ridge.

He fought wise battles with the flesh,

he read pure learning.

He stitched, he hoisted sail tops,

a sage across seas, his prize a kingdom.

This poetry is not, as later medieval Irish poetry can be, the wan appreciation of Nature’s delicate charms. This man is not looking out of a window. Nor is it mystic. He is not contemplating another world. He loves this one and his love of it and of his patron saint has emerged from struggle. Beccan seems to be purified by his understanding. He has been out in the storm and has felt the waves beat for days and months on his shore. His mind now is as clear, unadorned and direct as the holy ringed-cross stone which this poet, perhaps, may also have made.

I have often walked the Shiants wondering where the hermit may have lived; which of the favoured five or six spots he might have chosen. It might well be at the place called Annat, a soft and welcoming nick in the ragged west side of Garbh Eilean. It is where I would have chosen. The long gentle valley called Glaic na Crotha, ‘the valley of the cattle’, runs across the island here from the north cliffs to the south-western shore. The little stream in the valley gathers pace as it drops and the buttercups and watermint cluster around it. Down at the bottom, the land flattens out into a little seaside meadowy apron beside a sharp rocky inlet. It would be a beautiful place to live and I have sometimes brought a tent here to spend the night, seeing the last of the light falling on the mountains in Skye to the south (they are hidden from the house on Eilean an Tighe) and waking in the morning to find the sun warming the turf. There’s a stony beach here which always has driftwood on it and the smoke from the breakfast fire slowly spirals upwards. All morning you can lie with your nose buried in the tweedy scents which the warming grasses give off. Beccan’s seas stretch out in front of you to the southern islands of the Outer Hebrides, trailing off to Barra Head, and you can imagine what this place might have been like thirteen hundred years ago.

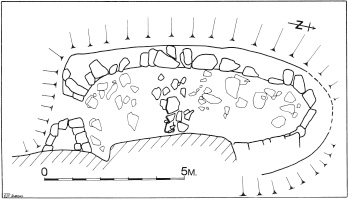

It is a numinous place and the feeling here is quite unlike any other on the islands. This is not a wild corner. It is calm but not quite as domestic as the settlements on House Island. It has a sense of privacy and of removal from the peopled world of Eilean an Tighe. Annat bears the same relationship to the Shiants as the Shiants do to the rest of the world. I like to think of it as the place the hermit chose. It has certainly been lived in for a long time and, as Pat Foster showed me, there are clear signs of prehistoric buildings here: a large platform for a neolithic house, a round Bronze Age house and a D-shaped enclosure which may have been to keep stock in. So it might be the ideal place for a hermit: somewhere that had been lived in in the ancient past and was suitable for human occupation but in the seventh or eighth centuries happened to be empty.

It is possible to investigate this quite closely. On the maps it is called Airighean na h-Annaid, which means ‘the shielings or summer pastures of the Annaid’. Annaid itself, a place-name which in the form of ‘Annat’ or ‘Annet’ occurs throughout Scotland, comes from the early Irish word andóit, from the late Latin antitas, a contraction of antiquitas, meaning simply ‘the ancient’. In Ireland, andóit acquired the more particular meaning of the oldest church of a local community, founded by the saint who had first brought Christianity there and whose relics this church would often continue to enshrine. Tithes were due to this mother-church and in turn it had a duty of pastoral care over the parish that surrounded it. These significances did not need to be enormous in scale. There is no reason why the Shiant mother-church should have had any influence beyond the Shiants themselves.

The Celtic place-name scholar William J Watson wrote in the 1920s that ‘Annats are often in places that are now and must always have been rather remote and out of the way. But wherever there is an annat there are traces of an ancient chapel or cemetery or both. Very often, too, the annat adjoins a fine well or clear stream.’

The stream that runs down at the Shiant annat, trickling between mosses and over the hot rocks, with wild thyme and clover growing in the grass beside it, full of the cool of the moor that it drains, is indeed some of the sweetest of all Shiant waters.

So is this, in its sun-trap warmth on these wind-besieged islands, where the church of Beccan (or his contemporary) might have stood? Maybe. But, as Pat Foster established, the cemetery is on Eilean an Tighe and one might, as William Watson said, expect the cemetery to be in the place where the mother-church was. Thomas Owen Clancy has recently re-examined the question of annaids in Scotland. How come so many annaid place-names, he asks, which should, as the mother-churches, be central to the human geography of Scotland, turn out, as William Watson said, to be on the margins? He provides a possible explanation. Many annaid place-names are combined, as it is in the Shiants, with other elements: the pastures of the annaid, the bank of the annaid, the well of the annaid, the field of the annaid:

These places need not themselves be the places referred to as the annaid; they may express their relationship, by property, use or general proximity, to the local ‘mother church.’ We should not necessarily expect to find evidence of church-sites at the location of such names, but perhaps somewhere else, even at some distance.

So the Garbh Eilean pastures of the Annat might have been no more than the church’s glebe, a place called ‘Church Meadows’, and the church itself would have been where the graveyard is, on the island known until the mid-nineteenth century as Eilean na Cille, ‘the Island of the Church’. A careful examination of that site on Eilean an Tighe does in fact reveal a pair of banks, set at some distance back from the graveyard and its associated buildings, each bank running from the cliff foot to the shore, making an enclosure, as was the norm, around the holy site. Although there is nothing that can be firmly identified now as the ruins of the church, many nineteenth-century travellers had a few tumbled stones on Eilean an Tighe described to them as the hermit’s church-cum-residence. It looks, in other words, as if he did not live at Annat but on Eilean an Tighe, near the present house.

That is far from certain, though. The Gaelic scholar Aidan Macdonald has also looked at the annaid question and has come up with precisely the opposite answer to Thomas Clancy’s. Macdonald sees in the pattern of distribution of the annaid name – remote, apparently abandoned, never the centre of later ecclesiastical development – evidence not of continuity but of disruption. The technical and legal sense of andoit can never have mattered much. ‘Place-names are usually simple, straightforward and descriptive, and specialist technicalities would tend to be forgotten, if ever properly appreciated, by a non-specialist population.’ The names mark the sites of ‘churches of any kind which were abandoned and subsequently replaced but not, for a variety of reasons, at the same sites.’ Annaid, in this version, means simply ‘old church’.

This, of course, is an intriguing possibility on the Shiants. The lovely Annat on Garbh Eilean is just the place a Beccan might have chosen: good soil, good water, a place where you can bring a boat alongside, even if hauling it up is difficult. People had lived there before and there was building stone to hand. It may be that the prime site near the landing beach on Eilean an Tighe was already occupied by Pictish pagans. Annat was the corner into which the hermit could squeeze, not perfect but not bad either and perhaps separated by a mile or so from the people on the other island.

For some reason, that old church was abandoned, but not forgotten, and a new one built on the island which then became known as the Island of the Church. The consciousness of the ‘antique’, of what had been there before, survived until the name was recorded by the Ordnance Survey in 1851. It may also have survived in one other detail. George Clayton Atkinson, the Newcastle naturalist, was told in the 1830s that the island now called Garbh Eilean (Rough Island) was known as ‘St Culme’, a clear corruption of the name of Columba. Rumours of a dedication to St Columba had also reached John Macculloch’s ears ten years earlier. The church on Eilean an Tighe was said in the 1690s by Martin Martin to be dedicated to the Virgin. But is it possible that the old church at Annat on Garbh Eilean, Beccan’s church, for want of a better shorthand, was in fact dedicated to the saint he loved?

‘Annaid’ is a term which came into use in the ninth and tenth centuries and Aidan Macdonald is unequivocal about the reasons for its sudden appearance: Norse raids. The Hebrides were first plundered in 798. Raids on Iona continued throughout the ninth century and Norsemen were living in the Hebrides by the 850s. The scatter of annaids were all readily accessible from the sea or river valleys or the routes between them. These abandoned sites marked, Macdonald thought, the terrifying destruction from the north.

Is that what happened here? Archaeology has yet to address that question, if it ever can. But elsewhere in the Hebrides, at a site called The Udal in North Uist, it is quite clear that the Norse arrived suddenly, comprehensively and violently. A settlement which had been there, in much the same form, for five hundred years was razed and immediately built over. Everything which the earlier inhabitants had used in the way of buildings, pots, bonework, metalwork, plates and buckets disappeared overnight in the middle of the ninth century, to be replaced by their Viking equivalents. In the new, high-stress environment, a small fort was built there, the first military architecture in two thousand years of human life at The Udal. The archaeologists looked for the faint, tell-tale traces of sand blown across the earlier levels before the new buildings were erected on the place. That would be the sign of a slow evolution, of natural abandonment and natural recolonisation. But there was nothing. It was a literal physical truth that the Norse buildings were put straight on top of the ruins of their predecessors. ‘The Vikings came without apparent cause, provocation or feud,’ Iain Crawford, the excavator of The Udal has written, ‘and they were speaking an unintelligible tongue, like visitants from outer space.’

You can imagine that at the Shiants: the sudden arrival, the keels on the beach stones, the leaping from the bow, the walk around the corner, and then the careless erasure of lives and meanings, the leaving of bodies for the ravens, as one Norse saga after another describes it, the destruction of buildings, the burning of their contents, the ridiculing of the odds and ends they might have found there, the laughter at the easy win, the excitement in slaughter. ‘Agony, death and horror are riding and revelling,’ one English sailor wrote after Trafalgar. ‘To see and hear this! What a maddening of the brain it causes. Yet it is a delirium of joy, a very fury of delight!’ Here on the Shiants, as the blood slopped on the shore and seeped into the grasses, those would have been the words in the air. It was a blood culture. Blood was the mortar of the Viking civilisation.

Soon enough, the Norsemen made their mark. Up above the coastal shelf on Eilean an Tighe, tucked into a fold in the ground so that it is invisible from the sea but commands a wide view of it to the west and the south, not calmly and confidently set on the domestic bench of flat land but hidden, nervous, aware of the possibilities of violence emerging from the Minch, is what might be a Norse house.

It is boat-shaped, using a natural cliff as one wall, and with the foundations of a dividing wall half-way along it. It has the look of a Norse building. There is another of the same form, also tucked into a hidden shelf, also invisible from the sea, two hundred yards or so to the north. Both buildings await excavation but here, perhaps, are the houses of the people who destroyed the church at Annat and who replaced Beccan’s ‘bright crowd of chancels’ with something that at this distance seems colder and meaner.

On the hillside above what is perhaps the Norse long house, is another enigmatic monument. Mary Macleod, the Western Isles County Archaeologist, who came over to the Shiants for a day to inspect what Pat Foster and his team had done, was reluctant to accept this arrangement of stones as anything more than the fragmentary rubble of a couple of field walls, meeting at a corner. Her professional scepticism was proper enough and any more explicit identification can only be tentative. Nevertheless, the romantic landowner, wanting to see in his islands a reliquary for all that is most glamorous in the past, persists in reading these stones in the best possible light.

They are loosely arranged in the form of a boat, about eighteen feet long, just outreaching Freyja, with a wide, flat stone set crosswise at the stern, another for a thwart amidships and a third, taller, at the front, curved up and back in the way of the Viking stem post found on the island of Eigg. Pat Foster will describe this as nothing more than a ‘Boat-Shaped Stone Setting’. Similar structures in Scandinavia, if far more precisely and neatly made, have housed Norse graves. This one is aligned on Dunvegan Head in Skye, thirty miles to the south, the seamark on the Viking route to Dublin. There is another Boat-Shaped Stone Setting high on the far end of Garbh Eilean, almost on the lip of the northern cliffs, arranged on rising ground, as if breasting a wave coming down from the north.

That one is aligned precisely the other way, on the dominant outline of Kebock Head in Lewis, en route to Stornoway and the north. In the summer, purple orchids are clustered next to the stones and the fulmars from the cliffs below cut easy discs in the air above them.

Are these Norse graves? I can only say, in the face of professional scepticism, that I hope so. If they were ever excavated, it is unlikely that anything would be found. The acidity in the turf will have eaten away all evidence.

That doesn’t matter to me. The Shiants are a place where the deep past seems more nakedly present than any other I know. Perhaps it is because the islands are so pristine in their silence. Perhaps it is this landscape’s ability to retain the marks of previous lives. Little here is overlaid, as it is elsewhere, with the thick mulch of recent events. The physical remains lie just beneath the surface, scarcely skinned in turf. Modernity is almost absent, cut off by the Minch. Crossing that sea, whether in Freyja or in any boat, pares away the fat. The surrounding sea makes you, for some reason, more attuned to habits and ideas that are unlike all the usual daily traffic of the mind.

This is almost undiscussable. It is a strange effect, existing only at the margins. Try to hold it or define it and it slips away like mercury between the fingers. Sometimes I have felt, especially in Freyja, and above all when out on the sea late in the evening, that I only have to look to the other end of the boat for some other figure to be there, sorting out the ropes, wrapping the plaid around them. Of course they never are. Of course not. The world is not like that, but there is often something else in the wind, which is, I suppose, the potential that they might be there, quite ordinarily, without any kind of fuss being made. If this were a film, the camera would move casually past them, panning around the black bodies of the islands, the lace of surf and the green glow of the evening sky, catching the hunched figures on the forward thwart as no more remarkable a presence than my own in the stern or the creels amidships, the tide running with us or the long, haunted wailing of the seals.

Being out on the sea at night brings some kind of connection with an older and more essential world. It is not as foreign as people tend to imagine. Men have been at home on it since the Stone Age. The Hebrides are littered with the remains of Bronze Age farms, whose inhabitants must often have crossed these waters with their implements and their stock on board. Imagine cattle in those ancient boats, how impossible that must have been! At least you can cross the Minch or the Sea of the Hebrides in a day, and you can see your destination as you begin. What amazes me more is the idea of the Vikings bringing their herds of cattle with them in open boats across the North Sea, plunging for days across that hostile grey territory, navigating by instinct as much as anything, with the animals increasingly restless, trussed presumably, longing for the destination.

Stripped as it is of context, and with the modernity of the world sliced away, it is easier to imagine the past at sea at night than in any other circumstances. Fixing the tiller with a length of rope, I leant over the bow late one evening and put my head right down there where the water rose and broke around the stem post. Freyja sailed herself in the quiet breeze of the night. The loom from the lighthouse on Scalpay swept out across the Sound, three white flashes once every twenty seconds. The buoy marking Damhag flickered its quick uninterrupted green. The surf on the Galtas came and went, the teeth of a long, white smile, and the boat sailed on as though another hand were on the helm.