10

IN MIDSUMMER, AS THE BIRDS were proliferating around me, and as the cotton grass began to show its white-tufted pennants in the bogs, as the flag irises flowered in the ditches and the meadowsweet bubbled out in the protected corners by the cliffs, the time had come to address the central question of the Shiants. What had happened here? What history was there here? What explained its emptiness now and the remains of buildings distributed across the islands? The old buildings as I walked across them reminded me of a summer beach after the warmth of the day has gone. You can see where each family has been, their scufflings in the sand, the one or two sweet wrappers and scraps of paper left behind, a can or two, the holes where their windbreak had stood, the marks of dug-in toes beside the legs of a deck chair, all the diagnostic signals of life once lived but now finished, waiting for the tide to roll in over it. That, translated into moss and tumbled stone, was the condition of the Shiants.

I wanted to find out more about the islands and that was why I had asked Pat Foster to bring his team of archaeologists with him to the Shiants. He had now done his survey. He had made a few tentative guesses as to the nature of the remains he had identified. Now the time had come to dig. What has emerged from their archaeology, and from the historical documents which I gathered, is a rich and poignant story of a community coming to an end. Its struggles and its ingenuities, the changing circumstances with which it had to deal, its final collapse: all that is revealed. What before had been a contourless silence can now be seen as a tiny island microcosm of Highland history at its most critical juncture, the centuries between 1600 and 1800.

To understand that story, one must go back a little earlier. I asked the leading expert on the history of the Hebridean landscape, Professor Robert Dodgshon, to come to the islands for a couple of days and walk across them with me. The kind of detailed analysis of a single site or building which archaeology can provide needs the broader context of the landscape historian. No island house could make sense without its surrounding fields and sea.

It is one of the repeated pleasures of life to witness an expert presented with a new set of data. Arriving off Malcolm MacLeod’s boat from Stornoway one morning, Robert could scarcely sit down for a cup of tea in the house before rushing out to see what the Shiants had to say for themselves. An Atlantic storm was slashing around us like a carwash but it made no difference to the scholarly appetite.

What he impressed on me again and again over the next forty-eight hours was never to think of fixity in a place like this. Human occupation of the Shiants would always have come and gone like the tides, a filling and ebbing, a restless geography. ‘Life here,’ the professor said to me from the depths of his huddled waterproofs as we stood high on the inland flank of Eilean an Tighe, ‘was never some fixed version of the ancient surviving into the modern age.’ It would have been a consistently responsive pattern, adapting to its own growth and its own travails, extending its fingers into every part of its natural resource, beaten back at times, only to refill the spaces left by those withdrawals. But that very pattern of give and take, mimicking a natural population, is itself a form of permanence, the kind of existence which French historians have called the longue durée – a nearly changeless continuing for century after century.

Of course change did occur. Eight hundred years ago, the pattern might have been very much what you can see in the Celtic landscapes of Cornwall or Wales: family farms, each with its own arable and sweet grazing, with shared rough grazing on the heights. The Shiants would have been a cluster of privacies, with a form of communal grout between them. It is not difficult to imagine them in the five core places: at Annat and the Bagh on Garbh Eilean, by the shore and in the central valley on Eilean an Tighe, on the heights of Eilean Mhuire. Amazingly, you can still see the footings of such a farmstead on the rich ground just beside the natural arch on Garbh Eilean: a house, a barn, a byre and a garden enclosure, just uphill from a fresh-running spring.

It is a lovely place. I have camped there in the past and you see something from these soft green pastures which is hidden from the house on Eilean an Tighe: dawn over the mainland of Scotland, the tangerine sun lifting up over the ragged mountains in Torridon thirty miles to the east with slabs of orange light daubed across the Minch at your feet. Whoever lived here in the distant past, while needing to cower from the terrible exposure here to an easterly gale, must always have loved those wonderful summer mornings flooding in across the sea.

Elsewhere those early medieval farms have been obscured by later building but in the larger landscape one can make out the field walls which must have belonged to those farms, the careful delineation of private holdings. In their lichened and crumbling state, their lines infused with a habit of use, these walls are the most beautiful of ancient marks on the ground. They can only remain enigmatic, as neither archaeology nor landscape history has developed a way of dating them. They are as uninterpretable as the scratches and borings left by generations of schoolboys in a wooden desk; repeated private etchings, their point – beyond the obvious: keep the cattle out of the corn – forgotten.

At some point in the Middle Ages, all of this came to an end. The small farmsteads on Garbh Eilean were abandoned and the system known as run-rig imposed. Each year, narrow strips of arable land were parcelled out among the families of the community, each family receiving different lots every year, as a form of communal fairness. These are the strips you can see all over the Hebrides, often now called ‘lazybeds’, a term invented by late eighteenth-century ‘improvers’, perhaps because by this system only half the ground was cultivated, the other half devoted to wide drainage ditches. Robert Dodgshon told me something I had never even considered before: that this strip system, which is so deeply embedded in the visual image of the Hebrides, may well be an alien import. ‘Don’t the strips remind you of something else?’ he asked me as we walked around, muffled in our waterproofs on a bitter, slashing summer day.

‘The strip systems in open fields?’ I guessed rather wildly, trying to drag an image of huge East Anglian field systems to the islands. That is what he meant. Far from being an indigenous Celtic proto-communism – as everyone likes to imagine – the landscape of cultivated ridges may well be an imposition by feudal landlords in a period of medieval regularisation. The earlier, indigenous, private family farms, were at some point transformed into a shared landscape, a communalisation similar in its way to the collectivisation of farms in Soviet Europe after the war.

There is no saying when it happened here. It may have been after the Black Death in the fourteenth century, which would have devastated the families here, as it did elsewhere in the Hebrides. The older farms may have been abandoned in death and never reoccupied. Or perhaps at an earlier time of sudden and momentous disruption.

This was, after all, the world of the clan. No overarching authority was recognised here for most of the Middle Ages. Each clan, as long as it accepted the fact of vendetta, could attack what it liked and steal what it liked from any other. Violence, and the theft above all of food in the form of cattle, was part of the clan world. The Shiants, at the centre of the Minch, were on the front line of opposing bands based in northern Skye, Lewis, Harris and further south in the Hebrides. The feuds between them continued for century after century and two incidents in particular occurred within sight of these shores.

There was, first of all, the fatal moment, perhaps in the twelfth or thirteenth century, when the glory of the Nicolsons came to a sudden and irrevocable end in the Sound of Shiant. They had owned the whole of Lewis, with a castle probably at Stornoway, and much of Assynt on the mainland opposite. The clan was known for the wealth of its farmlands: ‘Clan MacNicol of the porridge and barley bannocks’. John Morison of Bragar in Lewis, writing in about 1680, described the mournful moment: ‘Torquill, son of Claudius [a seventeenth-century aggrandisement of the name Macleod] did violently espouse Macknaicle’s only daughter, and cutte off Immediatelie the whole race of Macknaicle which is also callede and possessed himself with the whole Lews [all of Lewis].’

The Nicolsons retreated to Trotternish in northern Skye and things have never been quite the same since. Is the abandonment of the Garbh Eilean farms to be dated to the destruction of the Nicolsons as people to be reckoned with?

More enigmatically, the huge dark bay on the eastern side of Eilean Mhuire, filled in summer with more guillemots than any other part of the islands, crowding there on rock after rock around the whole rim of the mile-long bay, is called Bagh Chlann Neill. It might mean the Bay of the MacNeils but nowhere on the Shiants, nor in Pairc opposite, has ever belonged to the MacNeils. Or perhaps it refers to the family of Nial Macleod, the defender of Lewis against the Fife Adventurers at the beginning of the seventeenth century, whom he once attacked with ‘two hundred barbarous bludie wickit Hielandmen’. There is no telling.

There are other bays with the same name in several places in the Hebrides, in Scalpay, Loch Maddy in Uist, between Grimsay and Ronay, and on the north-western side of Berneray in Lewis. There is one in particular in Coll, which is also called Slochd na Dunach or the Pit of Havoc where, it is said, ‘a fearful slaughter of the Maclean’s enemy is still remembered.’ No such story attaches to the Bagh Chlann Neill here, but it is a place where fishing boats do still come in to shelter in a strong southwesterly. It is not inconceivable that some MacNeils were caught there one day, perhaps by the sudden violence of the Macleods, rounding the corner by Seann Chaisteal in their birlinns. The MacNeils would have been trapped in the bay, slashed at by the Macleods, and finally murdered, before the dead were hoisted overboard, leaving only their name on the blood-slicked water. Had the MacNeils been thinking of taking over the riches of Eilean Mhuire? Was it that kind of threat which forced the Shiant Islanders to retreat to Eilean an Tighe?

Those are unanswerable questions and the longue durée continues through and past them. Birds, fish, livestock, vegetables and cereals, clay, peat, driftwood, stone: these were the materials out of which life was made. Metal was nearly absent. Roofs, creels and fish-traps, even the strakes of boats, weren’t pinned or nailed but woven or bound together with ropes made from heather, hair, grass or roots. There was nothing special about this. Life here would not have been essentially different from life on the shores of the sea lochs in Lewis, Skye or the mainland. An island existence was neither more privileged nor more deprived than anywhere else. In a world without roads, and only long, wet, sludgy paths across moorland, to be on the Shiants was to have the benefit of the good soils, the riches of the birds and fish. It was not to be deprived of anything the mainland could offer. It was a sea room with sea room, a place enlarged by its circumstances, not confined by them. Isolation and insularity were not the same thing.

This constancy and continuity makes an enormous problem for archaeologists. Not only are the materials of one age, even one millennium, barely distinguishable from those of another, but one age consistently uses the materials of another. A modern sheep pen or fank reuses the stones of a nineteenth-century summer shieling, which reuses the stones of a seventeenth-century house which reuses the stones of an Iron Age roundhouse, which has itself reused the remains of a Bronze Age dwelling. An island can only survive by recycling.

It was not quite a closed system. The outside world had its impacts, but the impact was contingent. Things, people and ideas all arrived at the shore, but they scarcely changed the nature of the system they found. In the summer of 1999, on the beach between Eilean an Tighe and Garbh Eilean, a pebble of pumice was washed up, light enough to float. It had come, almost certainly, from the volcano erupting that year in Montserrat in the Caribbean. Others, identical to it, had been found on beaches in Tiree. A few days later, the large, glossy heart-shaped Molucca bean of a plant called Entada gigas, always known in the Hebrides as Mary’s Nut, washed up, carried here perhaps from the shores of Nicaragua, where it grows above the sandy beaches. Columbus is said to have found these sea-hearts on the coast of the Azores and to have set out westwards in search of the trees that had shed them.

Until about 1600, that near self-sufficiency had defined the Shiants’ relationship to the rest of the world. The pumice is added to the beach, the nutrients from the rotting sea-heart are added to the life-system of the islands, which continue on their way, absorbent and indifferent. But between about 1600 and about 1800 that immensity of the longue durée comes to an end. This is the period of the Shiants’ pivotal crisis. By about 1800, the islands were no longer permanently occupied. No one could be persuaded to stay here and the islands, from having been central to their own existence for millennia, had started to become marginal to a world whose focus was elsewhere. These islands, in other words, had become ‘remote’ for the first time. Insularity became identified with isolation and that was their death knell. Something fatal had happened to the Shiants: the arrival of the modern.

For the modern world, and for modern consciousness, the Shiants did not have what was necessary: closeness to markets, either for sale and for supply, nor access to the materials of civilisation. This moment of crisis, this shift from one type of world, which had existed, more or less, since the end of the Ice Age, to another which is recognisably like the one we now inhabit, would, I realised, be the most revelatory period in the Shiants’ history. It was the period I wanted to investigate in the archaeological excavation we carried out on Eilean an Tighe in the summer of 2000. What happened here? How quick was the change? How sudden the departure? How agonised the experience? Could answers to any of these questions be sifted from the silent evidence which archaeology provides?

When Pat Foster arrived with his team of Czechs in the summer of 2000, we decided what to excavate the first evening. I was already on the islands, having sailed out a few days before, and had swept and tidied the house as if there were no tomorrow. The rat-poisoning campaign in the spring had done its work. There was no sign and no smell of the beasts inside. A couple of poison-desiccated bodies curled up in plastic bags was the only reminder. I burnt them.

The islands were looking their most severe. Cloud was down on the tops and a grin of surf lined the northern shores. The place, when it is like this, can feel like the deck of a trawler. The Czechs looked around them, a little cold and a little disconsolate. Were they really going to be spending two weeks on these grim, sandless, northern rocks? Was this really my apology for a house? Where was the place where we could have a picnic by the shore? But Pat Foster is a richly inspiring person. We walked along the bench of flat land beside the sea looking at bumps and hollows. Anything here that we should excavate? he asked. Anything that I liked the look of? Perhaps not. Too much rubbish in the ruins, too complex a set of overlying structures: modern on eighteenth-century on medieval on prehistoric. Even from the look of the landscape, you could tell that layered complexity was inevitable here. This was the place that had more to offer than any other on the islands. It should not be the site we first addressed.

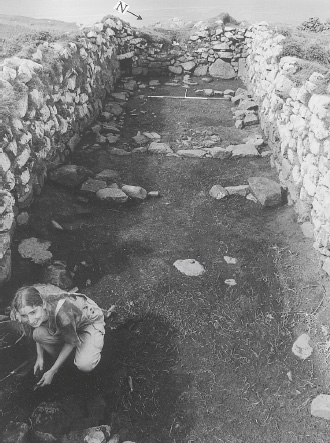

Petr Limburský, who had been with Pat on Barra, excavating the site of the neolithic house at Allt Chrisal, is a man of precision and gentleness, with a head as massive as Beethoven’s and a slightly distant, romantic air. He had gone for a longer, wider walk from which he came back excited. There was a site that seemed ideal, up in the central valley of Eilean an Tighe. It was the largest house, almost forty feet long internally and ten feet wide, with double-skinned walls that were themselves three feet thick. This building was clearly part of a complex.

Small barns had been built next to it, one to the north and one to the south, and all three structures were enclosed within a kind of courtyard within which haystacks would have stood, protected by the surrounding wall from any wandering beasts. It was, in other words, a farmstead. The walls of the main building were still standing three or four feet high. They had not been robbed or reused. It was a fair guess that this building had last been used when the Shiants were last permanently occupied in the 1700s. The shepherds who had come here in the nineteenth century lived down near the shore, almost certainly on the site of the present house. Pieces of Victorian Dundee marmalade jars and the blue nineteenth-century willow-pattern china can be found quite easily on the beach in front of the house where those Victorian Hebrideans threw or dropped them. Up here, though, on a dry platform of ground where the yellow-flowered silverweed grows in thick profusion, was a place not overlaid by the present or the more recent past. This is where we would dig.

The following morning, the weather had changed to a pale iris-blue sky. Bubbled clouds streamed in from Ireland. The Shiants felt Arctic and looked Provençal. The gulls honked and cacked when we entered their breeding grounds. The wind cut across the high plateau site and above it, hardly glimpsed, but heard unbroken for two weeks, a lark sang, rising and falling in the sunshine, its trembling unbroken glissando the ever-present accompaniment to this delving into the Shiants’ past.

The work was exhausting and heavy at first, cutting the nettles, slicing off the layer of turf in which they grew, stacking the turf for later reuse, moving the boulders which had clearly fallen from the walls and piling them alongside the house. Once cleared, the slow and meticulous excavation could begin, distinguishing colours of earth, feeling as if in deep snow for the contours of the underlying realities.

As the seven archaeologists scraped away, shaving off successive layers, it soon became clear that the time we had would not be enough to discover everything about the building or its site. It was too big, but we drove on day after day, performing our gradual surgery on the body, exfoliating its past lives one by one. By the end of the allotted fortnight we had not reached anything like its origins. The layers were continuing deep below us. Our final day was spent piling the soil back on to the surfaces we had exposed, and returfing them, to protect the archaeology from the sheep which would wander in here during the winter. Only finally, on the last afternoon, with the sky now grey above us, and spits of rain flecking out of the north-west, with our hoods up, did we light a small peat fire on the spot where one of the hearths had been found. Dry bracken was the kindling and gloved fingers the windbreaks until the fire took and we ate chocolate around its blue, intimate flame. The deeper history of this site, as of many on the Shiants, awaits the excavations of later years.

What we found is enough, with some conjecture and with the help of one or two documents, to re-establish a version of what happened here on that hinge between the ancient and the modern, stretching from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries. Of course, archaeology discovers its story back to front. It finds conclusion and ending first. Origins and beginnings are the last to emerge. And so the story here is not the story as it came to us on those beautiful summer days, with the lark decanting its heart twice as high again as the house is above the sea. This is the story of events as I think they might have occurred.

BLACK HOUSE ON EILEAN AN TIGHE

Plan

Conjectural reconstruction

Setting

Looking west during excavation, summer 2000

We had no time to look into the south barn or byre at all. It remains covered with its mat of nettles and silverweed, both marks of human and animal occupation and – not to be too delicate about this – defecation. It was always said that women in the Hebrides should relieve themselves with the cattle and the men with the horses. The human manure was added as an equally precious resource to that of their livestock. Much of the disgust of the enlightened eighteenth-century travellers stemmed from this intimacy of everyday life with the substance an urban civilisation thought of as sewage and which was considered here as the source of next year’s bread. That wrinkling of the sophisticated nose encompasses the revolution of this period. What one harboured, the other reviled; what one considered an essential part of the closed loop of their lives, the other wished to see disposed of as invisibly as possible. What the Hebrides saw as cyclical, the visitors saw as linear, a one-way process, a model not of the cycle of fertility but of the line of production.

It is a habit that persists with us. Modern visitors to the islands always over-cater in one particular commodity: loo paper. About forty rolls of it clutter the back of the cupboard in the modern house, testament to a modern anxiety. I have taken to using seaweed myself and although I would advise against both laminaria (leathery) and serrated wrack (prickly) or any of the red seaweeds (tendency to disintegrate) I can recommend bladder wrack, a saline swab of the most comfortable and effective kind.

In 2000, we concentrated on two areas: the inside of the house and the north barn.

The earliest layers are the most obscure and in the house itself, they were no more than glimpsed in a single trench – or sondage, a sounding, as the archaeologists call it – cut by Linda Čihaková. There are a pair of stone-lined and stone-capped drains in here. Linda removed the dark mud with which they were filled and found a baked clay floor in the bottom of each of them. This level is almost a foot and a half below the eighteenth-century floor and is perhaps the floor of a medieval house. At the same level in the barn, just above some building foundations, a small copper brooch was found, perhaps from the mid- to late-sixteenth century.

It is only an inch and a half across and it is not a rich thing, not in the same class as the torc, a domestic object which would have pinned up a woman’s shawl. Others identical to it have been found in Lewis. The ring is incised with what looks, at first glance, like letters but are in fact the worn-away remains of a repeated moulding. Four small crosses are cut crudely into the metal at the cardinal points.

Can a picture be drawn from these enigmatic hints of Shiant life at this earliest of our excavated levels? These are the floors of the Shiants in the very late Middle Ages. There are people living on this island and perhaps on Eilean Mhuire. It is also the moment the islands are first mentioned in a document. In 1549, a man of whom almost nothing is known beyond his name and title, Donald Monro, Archdeacon of the Isles, perhaps Rector of St Columba’s Church in Eye, near Stornoway, made the first tour of the Hebrides, perhaps a pastoral inspection. He was coming north from Skye:

Northwart fra this Ile lyis the Ile callit Ellan Senta, callit in Inglish the saynt Ile, mair nor twa mile lang, verie profitable for corn, store and fisching, perteining to Mccloyd of the Leozus.

Be eist this lyis an Ile callit Senchastell [still the name of the rock off the eastern point of Eilean Mhuire] callit in Inglish the auld castell, ane strength full of corn and girsing, and wild fowl nests in it, and als fishing, perteining to Mccloyd of the Leozus.

Monro’s description of Garbh Eilean and Eilean an Tighe together, and of Eilean Mhuire as a separate possession of the Macleod chieftain of Lewis, hints at a possible history. By the time of Monro’s visit, the farmsteads on Garbh Eilean had already been left and that island was now farmed as one unit with Eilean an Tighe. The fertility of Eilean Mhuire, despite its terrible exposure to winter gales, had kept some people living there, with their own farming system of arable fields, hay meadows and grazing.

They are not a poor place, ‘verie profitable for corn, store and fisching’. The ‘wild fowl nests’ here are famous and if a fowl is a bird whose destiny is the pot, these people are eating them. There were some signs of green sticky clay next to the brooch, probably manure, so animals are kept inside over the winter where their manure builds up to be spread on the spring-time fields. It is perhaps a good time, a florescence for the islands.

Those early levels are immediately below the first true floor of what is now called a ‘blackhouse’, a nineteenth-century term, for what previously would have been called, quite simply, a house. It, too, is of clay, baked hard, reddened by the heat and perhaps by the mixture of peat ash, which is a wonderful soft ochre. The central drain was laid in this floor.

It is of course nearly impossible to assign dates to memories and ghosts of structures such as these. It is like trying to name ripples in the tide. But again one can make a guess. The first blackhouse is an improvement made, perhaps, in the last years of the sixteenth century. Its new floor and its new well-drained accommodation reflect the relative well-being of the period.

Immediately after it, though, comes the first sign of crisis. Quite briefly, perhaps for no more than a decade or so, the house is for some reason unroofed and unoccupied. A thin, dark layer of silt soil, no more than a couple of inches thick, is spread across the well-laid clay that preceded it. Sheep would have trampled in here, the nettles would have grown, died and rotted, people would have been absent. Why? Here, above all, on one of the most favoured places in the islands? The documents provide a possible answer.

Between about 1590 and 1615, anarchy overtook Lewis and its dependent islands. The disaster for the Macleods began with an accident, in all likelihood the worst ever to have occurred within sight of the Shiants. The heir to the Macleod possessions, Torquil Oighre, his second name meaning heir, the son of Rorie, Chief of the Lewis Macleods, when ‘sailing from the Lewes to troternes in the Ile of Skye with a hundred men perished with all his companie by ane extraordinarie storme and tempest.’ The bodies would have washed up on these beaches and been buried in the cemetery by the shore, without doubt the greatest number of dead ever seen on the Shiants.

The inheritance of the island possessions was now uncertain and a long, complicated and bloody feud followed in which Torquil’s younger brothers, three legitimate, by his father’s three wives, and three others illegitimate, by other women, plotted against and murdered each other, pulling in allies from the mainland, and slaughtering their followers in the episode known as ‘The Evil Trouble of the Lews’. The Macleods were violent heirs to their Viking inheritance. It was said that the Clan MacLeod, ‘were like pikes in the water, the oldest of them, if the biggest, eats the youngest of them.’ It was a turmoil of mutual destruction.

Is it possible that our thin layer of silt, a mark of abandonment and discontinuity, just above the level of sixteenth-century coherence, is the Shiants’ reflection of the Trouble of the Lews? Perhaps. And could it be this period of disruption and change also brought about the withdrawal from Eilean Mhuire, the concentration of people in what may have felt like the collective safety of Eilean an Tighe? That too is a possibility. Certainly by the end of the century, and from then on, the three islands are treated as a single group and the entire population was living on Eilean an Tighe.

The eventual beneficiaries of the chaos were the Mackenzies from Kintail on the mainland. They had tied themselves by marriage to the Macleods, and played a brilliant, many-stranded and double-crossing role in depriving both the Macleods and a band of would-be gentlemen colonists, the so-called Fife Adventurers, of Lewis. They paid over some money (a signal of change: the first time the Shiants were ever bought) and emerged the legalised victors in 1611. The Genealogie of the Surname of McKenzie since ther coming into Scotland, complied by John MacKenzie of Applecross in 1667, described how ‘The Lord Kintail having now bought ye right of ye Lewes he landed in ye Lewes wt 700 chosen men qr aft. [whereafter] ye taking away of some herschips [plunder] and some little skirmishes manie of ye inhabitants submitted themselves to him and took yr poones [possessions] of him.’

One of those transfers of land, and perhaps some of the herschips and maybe some little skirmishes, occurred on the Shiants. Certainly, the islands went from the Macleods to the Mackenzies, who became Earls of Seaforth, in honour of the grandest loch in the grandest landscape of their new island possession. A 1637 charter from the crown, confirming the grant of Lewis and its islands to Seaforth, names these little specks of their new acquisition quite explicitly: ‘Iland-Schant’. The Shiants were now Mackenzie country. When, a century later, in 1718, the first surviving rental of the Seaforth’s estate comes to ‘Shant’, the name of the tenant is ‘Kennith Mackenzie’. He is the first named occupant of the island, one of twenty-two Mackenzies, tenants-in-chief or tacksmen to the Seaforths, who were occupying the best farms and key properties in Lewis. This Kenneth Mackenzie had been on the islands at least since 1706 (he was one of the few tacksmen unable to attend the hearings in Stornoway in person, presumably because of the weather) and was perhaps the grandson of the Mackenzie who had landed one day in the early seventeenth century on the beach between Eilean an Tighe and Garbh Eilean, his keel sliding onshore, his boots slipping on the slithering cobbles, the large number of Mackenzies he had with him jumping from their boats, coming around the corner, past the wells, past the little church and cemetery and then doing, or perhaps only threatening, the immediate and familiar violence. There is no record here of the casual gore, but that is the story I read in the inch or two of darker soil in Linda Čihaková’s meticulous section: blood in the silt.

The abandonment of the house was brief and, over the silt soil created in the troubled interval, another floor was soon laid. It was made precisely like its predecessor: thick clay packed hard. Almost certainly, the clay came from the narrow band of Jurassic mud stones and shales just to the west of the natural arch on Garbh Eilean. That is the only outcrop of clay discovered on the Shiants and the little valley of the stream that runs down there looks as though it might have been artificially dug away. It would be a long, heavy job carrying it in creels down to the little beach there, rowing to the main landing beach and then carrying the loads up the trackway to the site of the house, but not impossible. They would probably have had ponies (there were horse bones in the eighteenth-century archaeological layers) and, besides, unremitting labour is the price of existence in a marginal world.

Contemporary with this floor is the strangest story – it hinges on dearth and the pressures which dearth places on revered customs – ever associated with the Shiants. It carries no date, but probably describes an event in the middle of the seventeenth century. Iain Dubh Chraidig came from Uig on the Atlantic shore of Lewis. Every year, many Uig men used to come over to Pairc, on the east side of Lewis, opposite the Shiants.

John Du used to go in summer to fish for saithe in the Sound of Shiant. On one of these occasions he took his mother with him, as there was no food to be got at home in Uig. Poor John was only there for a few days when his mother died, which left him at a loss what to do. He wanted to bury his mother at home in Uig – but he was at the same time loath to leave the fishing. So this is what he did. He removed the entrails from the corpse and placed the body in a cave, where it became mummified. And when he was done fishing, he took his mother’s body home to Uig, where he buried her alongside her husband.

Evisceration of a loved one was not unheard of in the Hebrides, particularly if the party was away from home and the corpse might rot before you got it back to hallowed ground. Some men from Ness gutted one of their company when they were away on the Summer Isles, buried the guts there and took the rest of him home to Lewis. Perhaps only the best of fishing, or the deepest of hunger, could justify it, but Ian Dubh was not being irreverent. The opposite in fact. He air-cured his mother because he loved and honoured her, not through indifference. There is still a cave on the coast of Pairc opposite the Shiants, just outside the mouth of Loch Bhrollúm, called Uamha Mhic Iain Duibh, ‘the Cave of the Son of Black John’, a name I cannot explain. But is it also ‘the Cave of the Eviscerated Mother’?

Just outside the house on the islands, at a level a decade or two later than this story, the excavators discovered a significant deposit. Underneath the foundations of the barn – in other words before the barn existed and, of course, after the medieval building on this site had disappeared – was a band of limpet shells and a few animal bones fifteen inches thick. Limpets are not very pleasant eating. I have tried them fried, boiled, with butter, garlic, parsley. Nothing can really disguise the basic sensation: you are eating someone else’s nose. Limpets are, in other words, famine food, a desperate recourse, the sort of protein to which you turn if all other options have gone.

This band of limpets, beneath the barn foundations and in use at the same time as the seventeenth-century floor in the house, consisted of about a hundred thousand shells. It is possible to do a little mathematics. Families in houses like this usually had about five members. It is possible to make a reasonably palatable and nutritious limpet broth, in which you can dip your bannocks, if you have them, with about twenty limpets per person. A limpet meal for the whole family in other words needs about a hundred limpets. In the time of birds, between April and August, and in the fair weather of summer when fish could be had, no one would turn to limpets for their protein. They are the famine food of winter and early spring, which in times of crisis might have been relied on for, say, half the meals for six months of the year. That would mean ninety days in which limpets had to feed the family. A famine year, then, might require something like nine thousand limpets. Although limpets were also used as bait, this pile, accumulated at some time in the late seventeenth century, may well represent something like ten years of famine.

That, in the 1680s, is almost exactly what there were. Martin Martin, travelling here in the following decade, refers briefly but conclusively to it. ‘They are great lovers of Musick,’ he says of the Lewismen, ‘and when I was there they gave an Account of eighteen men who could play on the Violin pretty well, without being taught: They are still very hospitable, but the late Years of Scarcity brought them very low, and many of the poor People have died by Famine.’

One can only imagine, from the accounts of other famines in other years, the reality of the horrors which that pile of limpets represents – the drawn faces, the broken tempers, the shortness with each other, the sense of the world being against you, the death of children, the endless, wearing diseases of the old, the temptations to selfishness, the squeezing of tolerances, the exhaustion and the despair. In that vestigial, mirror-image way of archaeology, the evidence of the horror of these years on the Shiants is quite apparent in the section cut through the house floors. After the famine food comes another abandonment. It all became too much. The people who lived in this house either died or left. Once again the roof disintegrated, or more likely in the Hebridean timber shortage, was removed and reused, and a seven-inch thick layer of grey silty soil accumulated over the floor on which the famine had been endured.

The occupied floor is quite different from the layer of abandonment above it. In the floor, astonishingly, you can see some of the smallest details of everyday life. The floor of the entire house is trug-shaped, rising towards the walls on either side and sinking towards the centre of the house, or like an old, thin mattress in a boarding house, slumped towards the middle, steep at the sides.

These are worn, swept places, with the dust broomed away from the hearth, out into the corners and edges. Within the section itself, you can make out the millimetre-thick bandings where a layer of black charcoal or of rusty peat ash has been swept out across the surface. It is a microscopic human landscape of powerful intimacy and unrelieved poignancy. These sweepings, keeping tidy in the face of catastrophe: what deeper sign of dignity is there than that? Above it, the silt layers are inert, a dead and formless accumulation of matter, indicating only absence, silence and the rain falling on forgotten lives.

This is the sequence of the Shiants – as of elsewhere in this marginal world – this coming and going, this suffering and resurgence, this courage in the face of a trying world. How long does that grey silt layer last? Thirty years perhaps? There is no way of telling. But eventually the people return, just as the puffin burrows on the north face of Garbh Eilean, abandoned in years when the population is falling, are eventually reoccupied and rehabilitated. Here, once again, perhaps around 1720, a new floor was made, again on the same principle, and burying the accumulated silt beneath it. It was a new beginning and easily the most sophisticated so far.

There are signs of change. A new stone-capped drain is installed along the south wall of the house. A stone-rimmed hearth is built roughly in the middle of the house and a line of stones makes a ‘step’ between the east and west end, that is between animals in the byre end and people around the hearth. A large area outside to the south and east is roughly paved and an extension, a barn or byre, is built to the north, on the site of the limpet pile. To a traveller from England or Lowland Scotland, this house might still have looked like a primitive habitation, the sort of thing that men occupied in a cultural backwater, ‘a Borneo or a Sumatra’, as Dr Johnson described the Hebrides in the 1770s. But compared with what had been here before, this was an improved and rationalised building. The fingertips of the Enlightenment had touched the Shiants.

It was under this floor that we found the inscribed cross stone from the hermit in the seventh century, face down, under the clay of the floor and deeply buried in the grey silt beneath it. The stone’s used and pock-marked surface looks like something which far from being tucked away or buried has been in constant, bruising use, dropped and picked up, battered in passing. The stones which most resemble it on Inishmurray in County Sligo (and others which have now been lost on Iona itself) were used even in the nineteenth century in rituals that crossed the borders of Christian and pre-Christian belief. Jerry O’Sullivan, the Irish archaeologist who is currently making a long and careful investigation of the early Christian remains on Inishmurray, guesses that the cross-inscribed stones there may have been used in penance, carried from from one site to another on the island as a form of ritual pilgrimage. The heavier the crime, the heavier the stone. In the nineteenth century, there are also records of them being used as instruments either to bless or to damn. Turned clockwise, or sunwise, they brought goodness; anti-clockwise a curse.

The late seventeenth and early eighteenth century was a time of potent magic in the Hebrides. Stones of almost any kind were used as charms. We found several smooth and beautiful pebbles both in the barn and the byre end of the house, as well as one elongated egg of the same Torridonian sandstone as the cross, all of which might have been used for a kind of magic on animals.

This was also the period, though, when magic was coming under attack from the rationalist ideas of the new Enlightenment. There was an incident off the Shiants at just this time which encapsulates that transition.

According to the late seventeenth-century manuscript chronicle of James Fraser, Minister of Wardlaw, now Kirkhill near Inverness, the accident happened early in 1671, somewhere between Lewis and the northern tip of Skye, perhaps in the tide-rip just south of the southern point of Eilean an Tighe:

This April, the Earle of Seaforth duelling [?dwelling] in the Lewes, a dreedful accident happened. His lady being brought to bed there, the Earle sent for John Garve M’kleud of rarsay, to witness the christning; and after the treat and solemnity of the feast, rarsay takes leave to go home, and, after a rant of drinking upon the shoare, went aboard off his birling and sailed away with a strong north gale off wind; and whether by giving too much saile and no ballast, or the unskillfulness of the seamen, or that they could not manage the strong Dut[ch] canvas saile, the boat whelmd, and all the men dround in view of the cost. The Laird and 16 of his kinsmen, the prime, perished; non of them ever found; a greyhound or two cast ashoare dead; and pieces of the birling. One Alexander Mackleoid of Lewes the night before had voice warning him thrice not to goe at [all] with rarsay, for all would drown in there return; yet he went with him, being infatuat, and dround [with] the rest. This account I had from Alexander his brother the summer after, Drunkness did the mischeife.

That is the rational, reasonable and modern explanation. A dissolute laird, drinking on shore, loved by his people, displaying to them, his hounds aboard, the birlinn with its new fast rig, no reef in the heavy canvas sail, so much less pliable and manageable than the traditional woollen sails, a racing journey home with the wind on the port quarter, ignorance perhaps of the Stream of the Blue Men and the holes that can suddenly appear in the sea there in front of you: these are the accidents with which a bravado culture always flirts.

But alongside this is another explanation. A raven, the bird of death, is said to have settled on the gunwale. Iain Garbh Macleod of Raasay reached for it, to strangle it, missed and drove in the upper strakes of the birlinn and the sea poured in. Why had the raven settled there? A rival of Iain Garbh’s for the lairdship of Raasay had paid a witch called, perhaps inevitably, Morag, to sit and watch for his return on the heights of Trotternish in northern Skye. For days she looked out northwards to the Shiants and the sea around them, waiting for Raasay’s sail. She had her daughters with her and asked them to fill a tub with well water and on its surface float an empty eggshell. When Raasay’s birlinn came into view, Morag continued to watch but told her daughters to go to the tub and to swirl the water with their hands as fast as it would go. They did what she asked and, in the whirlpool they made, the eggshell filled and sank; just at that moment a squall enveloped Raasay’s birlinn and the seventeen men were drowned. It was always said that on the anniversary of Iain Garbh’s death, the tide boils and stirs at just the place where he and his men went down.

The two versions of the story mark the beginning of the end of magic in the Hebrides. The burying of the cross stone beneath the blackhouse floor may well be another symptom of the same change. The floor under which it was found, made after about twenty years of abandonment which themselves followed the famine of the 1680s, can perhaps be dated somewhere soon after 1720. A document survives in the National Archives in Edinburgh which suggests a reason for the stone’s presence there. In the 1720s a definite and deliberate effort was made by the reformed church, here as elsewhere in the Hebrides, to bring the souls of the islanders more firmly under ecclesiastical control. The Reformation may be dated in Scotland to 1560 but out here, well beyond the reach of central control, what the reformers considered reprehensibly papist practices lurked on. The Edinburgh document is called ‘A PREPARED STATE, the Presbytery of SKYE, against the Heritor of the Lews’, dated 11 December 1722. The Heritor of the Lews, and the owner of the Shiants, was the Catholic Kenneth Mackenzie, Earl of Seaforth, who as a Jacobite had rebelled against the crown in 1715 and again in 1719, and after the failure of the rebellions had his estates confiscated by the Hanoverian crown. The presbyters from Skye were petitioning the commissioners in charge of the estate to divert some of its revenues to enhance the missionary efforts of the church in the untamed and backward-sliding Hebrides. Lewis, they said was spiritually in a parlous condition: ‘This wide and spacious Country, since the Abolition of Popery, was always served by Two Ministers, one at Starnway, the other at Barvas.’ That was nothing like good enough and the island should be subdivided, one of the new parishes to be Lochs:

the Church, Manse and Glebe to be at Keose, and the Minister to go to the South Skirts of the same, as he sees Occasion, there being but few families there who cannot attend the Ordinances at the ordinary place of worship. From the South-East corner of that Parish lies the Islands of Shant, Six miles from Shore, One of them only inhabited, and in it Five Families, making Twenty Examinable Persons; the Minister should repair thither twice in the Year, to preach and catechise.

The cross stone would have been seen by the new visiting ministers as a primitive totem of Christianity from before ‘the abolition of Popery’. In the reformed church’s emphasis on the intellectual clarity of the word, the cloud of magical associations clustering around the cross stone would have been anathema. Two sermons a year were preached in the little church by the shore here for the rest of the century. The minister would have been adamant. The stone was to be got rid of. But the Shiant Islanders did not destroy or break it. They buried it. Their precious totem was hidden but still kept, nurtured closely within a yard or two of where they all sat in the evening around the hearth, a secret presence in the substratum – you could say the subconscious – of the house.

This, too, is another version of the hinge of Shiant history. The turning of the stone face-down, the burying of its meanings in the dark, the denigration of an ancient way of thinking and its substitution with a clarified, authoritative Calvinism: all of this has seemed to Gaelic intellectuals, particularly in this century, like the turning-point in the culture of the Hebrides. Among the finds made in the blackhouse was a small folded copper alloy strip, about four inches long and half an inch wide. It may be part of a binding strip used in the eighteenth century to finish the outer edges of a Bible’s cover boards. Book replaces stone, word image and intellect the symbolic heart.

The Stornoway-born poet and Celtic scholar, Professor Derick Thomson, has written a poem ‘Am Boxachrocais’: ‘The Scarecrow’, stimulated, he told me, by no particular event but by ‘religious antagonism in the Lewis of my youth to secular music, dancing, even secular story-telling’, which envisages precisely the kind of moment in which the minister of Lochs walks into this blackhouse. As the biggest building at this end of the Shiants, it might well have been the cèilidh-house, the house in which people met, talked and told stories on the benches around the central hearth, and from which, when the evening came to an end, each would walk back to his own bed, his path lit by a glowing peat taken from this fire:

That night

the scarecrow came into the cèilidh-house:

a tall, thin black-haired man

wearing black clothes.

He sat on the bench

and the cards fell from our hands.

One man

was telling a folk-tale about Conall Gulban

and the words froze on his lips.

A woman was sitting on a stool,

singing songs, and he took the goodness out of her music.

But he did not leave us empty handed:

he gave us a new song,

and tales from the Middle East,

the fragments of the philosophy of Geneva,

and he swept the fire from the centre of the floor

and set a searing bonfire in our breasts.

Perhaps that is why the stone has such a strange air to it now. When Linda first found it buried in the floor, and when she first rolled it back to expose its carved face, I was there with her, to hear the shriek and see her look of horror at what she had revealed. All the holiness of the seventh-century hermit who made it is overlaid with the chill behind its burying. That act of joyless denial feels quite unholy and this first phase of the ending of the Shiants’ full life left me feeling troubled. I went for a walk that evening high on the east side of Eilean an Tighe, with the peregrines squawking like farmyard birds in the air beside me, and it came to me then, I think for the first time with the force of reality, that this was not a holiday place; that grim and persistent struggle had been the nature of life here; and that the replacement with a printed Gaelic Bible of a nurtured ancient stone was a symptom not of godliness but of empire, imposition, control and a sort of shrinking of life. The sea room of the Shiants had begun to die by the 1720s.