11

EVERY DAY, WE WOKE AT EIGHT, brushed our teeth in the little stream that runs down from the spring to the sea, rubbing the toothbrushes with a sprig of the watermint that grows there in summer, cooked our breakfast and ate it on the rocks outside the house, before dragging ourselves back up the hill to the site of the house and starting to excavate again. The story I can tell you here was not at all clear at the time. The evidence sifted and sorted by archaeologists is fragmentary at best. It is the science of the abandoned, the forgotten and the hidden. All you find is an impression of the life that gave rise to it, like the spoor of a hare in the grass, or the marks left by the wings of a grouse as it takes off from the snow on a bank. It is, in other words, a negative, a mould, from which the thing itself, the shape of life, has to be inferred. Only later when all the evidence is there in front of you and you can arrange it into a form that seems to make sense, can you understand what it was you were finding.

‘Record and collect, record and collect’: that was Pat Foster’s repeated mantra as we squatted with our little scraping trowels on the floor of the abandoned house and in the barn that was built in the 1720s on its northern side. Fragments of anything that might be significant, any flake of stone, bone or china, any shift in the colour of the soil, was picked up, photographed and drawn, with no idea whether it mattered or not. Everything mattered.

Nuance had to be read as carefully as a portraitist would investigate the face of his sitter. But nuance is not enough. Detail has to be set within a larger, overarching picture. I tried to apply what I had gathered of the documentary history to what was emerging from the excavation. It certainly became clear from the carefully preserved papers in the National Archives in Edinburgh that life wasn’t easy for the church on the islands and that the ministers had trouble supervising the Shiant flock. ‘The Lewis island is the most spacious and most remote of all the western islands’, the Skye Presbyters had moaned to the officials of the Society for Propagating Christian Knowledge in Scotland in 1722. Two decades later, in October 1744, Collin Mackenzie, Minister of Lochs, wrote a sad complaint bewailing his circumstances to ‘the Very Reverend the Moderator of the Committee for Reformation of the Highlands and Islands’. He wanted extra staff and a raise. Among the most burdensome of his expenses and difficulties were

the Islands of Shaint (a place well known to seafaring men) at the Distance of Sixteen miles of Sea and Land from the minister’s manse lying towards the south. In these islands are thirty examinable persons and the minister can go there in the summer and that at a vast expense being obliged to hire a boat and Crew. Moreover this parish is very discontiguous being divided by three long arms of the sea which renders it difficult for the minister to visit the people and for the people to visit him.

This is, of course, special pleading, but here too is another modern note: the first mention of any idea that the Shiants are difficult to get to. Within a few decades the idea of ‘remoteness’ would have brought the old life here to an end.

The population had increased between 1722 and 1744 from twenty to thirty ‘examinable persons’. These were people who were able to learn and repeat a catechism. Although the second figure only comes from Collin Mackenzie, the Minister of Lochs, and it was in his interest to exaggerate the numbers to justify his demand for more money, it might imply a total population of about forty, including both the younger children and perhaps the simple or the dumb. By the 1760s, the early economist John Walker, in his survey of the Hebrides, recorded twenty-two people on the Shiants, but his figures are often suspect and usually out of date. Almost certainly, that is an underestimate. Then there is a gap until 1796, when the Reverend Alexander Simson, by then minister in Lochs, wrote of the islands in the Statistical Account of the parish: ‘There is one family residing on the largest of the islands, for the purpose of attending the cattle.’

The picture is clear: a rising population until the middle years of the century and then a quite sudden collapse. It is here that the Shiant crisis reaches its sharpest point. This is not some slow and gradual sliding into the dark. The number of people increases, the level of work, business and energy has to grow to satisfy their demands, the resources of the islands are stretched and squeezed, the system is pushed to its limits, and then quite suddenly it breaks. After about 1770 – and there is no florid moment in the documents to which one can point as the end itself – life here for a self-sufficient community, for a complex of reasons, becomes unviable. The bulk of people leave and a single family remains, tending the animals, almost certainly not as sub-tenants of the man who rented the islands from the Seaforth estate, but as his employees. The relationship of people to the Shiants had for the first time in some five millennia become commercial, and the islands had entered the modern world.

Could our excavation of the eighteenth-century house, combined with an examination of the surrounding landscape, illuminate this fulcrum of Shiant history? We looked for the signs. When the house was improved in the 1720s, with its new south drain and external paving, the barn was built on its northern side. It was a sign of things going well. The old door that led out that way was blocked and cattle were kept in there. We dug into their manure, transformed over the centuries into a sticky green clay, near the base of the barn walls. Animals were all-important to the way anyone could live on the islands. The small black cows they had were a way of storing nutrients. They reduced people’s dependence on the seasons. They flattened out the difference between summer abundance and winter dearth. What the cattle ate on the high summer pastures of Garbh Eilean and Eilean an Tighe could be consumed by people in the form of beef, milk and all the dairy products, almost at will. The little cupboard built into the south-west corner of the house, the dampest and the coldest corner, raised a few inches above the floor, would probably have been the place in which the milk and cheese and butter would have been kept in earthernware pots, sometimes wrapped in moss to keep them cold. It was a tiny, cool room, a larder chilled by the wind. In bad years, when food was short, blood would be drained from a living cow and used to make a blood pudding. Sometimes, at the end of a winter inside, these valuable creatures were so weak that they had to be carried out to the spring pastures by their owners. And they were valuable. Twenty cows would make a very good dowry, but as Samuel Johnson said, ‘two cows are a decent fortune for one who pretends to no distinction.’ The rates of exchange were clearly established: one cow equalled three ewes equalled a spinning wheel equalled two blankets equalled a small chest or kist.

A cow was portable, or at least drivable, wealth. She also, with her winter manure which built up in the barns and byres, provided fertility for the vegetable gardens and plots of oats and barley. The lower end of the house, as well as the barn, was intended for animals. We found thick deposits of degraded manure there. The east wall of the house was taken down every spring, so that the manure could be shovelled out more easily, and then built back up. That too was obvious in the structure. The neat coursing of most of the house walls was almost completely absent at the east end, the stones haphazardly tumbled back together the last time the wall was reconstructed.

Before things got bad, the people here would also have used ponies to carry their heavy goods up from the beach, the manure to the fields, and maybe to plough the fields. As Robert Dodgshon has shown all over the Highlands and Islands, when a community has plenty of relatively fertile land for its population, and not too many mouths to feed, it makes sense to use a horse where you can. The ground needed to grow hay for its winter sustenance can be spared from growing arable crops. It is reckoned that in the Hebrides, with he traditional varieties of black oats and bere barley – low yielding but necessarily tough in the face of hostile weather – about five acres of cultivated ground were needed to feed a family of five. In the 1720s there were five Shiant families with twenty ‘examinable persons’ and perhaps another five children. They would have needed twenty-five acres of arable to keep themselves alive.

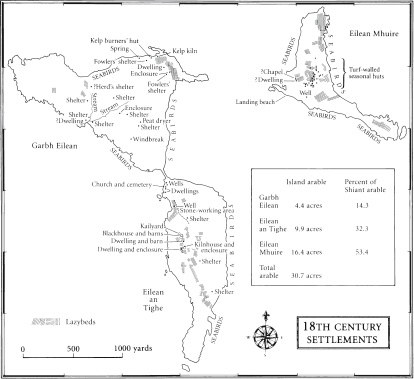

From walking the islands again and again and by looking carefully at large-scale air photographs, I have measured the amount of ground on the Shiants that was cultivated at some time in the past, or at least for which evidence survives in the form of cultivation ridges. The map shows how it divides.

Apart from the obvious conclusion that the sweetness of Mary was the foundation of all life here, and that Garbh Eilean was mainly for grazing (only 1.7% of the island under cultivation at any time, compared with 21.6% of Eilean Mhuire and 7.0% of Eilean an Tighe), the acreages themselves are significant. Thirty-odd acres of good ground (and one should perhaps reduce that figure because these measurements count all ground ever cultivated, some of it necessarily bad and sour) would be enough for about twenty-five people. As soon as the population started to climb towards forty, then serious difficulties – the prospect of malnutrition, illnesses that could not be shaken off, a loss of morale and eventual abandonment – became likely.

This was different to the crisis of the 1680s. Then, poor crops had failed to sustain a reasonable population. Now, the number of people was outstretching the land’s productivity even in a good year. Marginal ground had to be taken into production. The meadows on which the hay was grown to feed the ponies had to be cultivated and so the ponies themselves had to go. The use of the spade, or of the famous cas-chrom, the foot plough or crooked spade, which all visitors in the nineteenth century saw as evidence of a primitive agriculture still at work here, may in fact have been evidence of precisely the opposite: the pressure which the modern growth in population was bringing to bear. With many mouths to feed, a horse and its pasture cannot be afforded. But many mouths also come with many hands and the hand cultivation of enormous areas of ground, back-breaking labour as it is, may have been the only possibility for a Hebridean population under heavy duress from the mid-eighteenth century onwards. Lowland and English visitors, seeing the huge numbers of Hebrideans doing hand work on the fields compared the sight to the labour of Chinese coolies in the paddy fields of Asia.

Almost certainly, that is what happened here. As the century progressed, more and more land was dug. Even today, in some places, the sharp edges of the cultivation ridges show that these were dug by hand. A horse plough would leave a rounded contour, like the ridge and furrow of central England. The entire Shiant population would have been out there every spring, digging, quite literally, for their lives.

High on the windswept side of Eilean an Tighe, above the Norse house, is a field which is quite clearly cut out of rough pasture. It is poorly drained and acid land. Mountains of seaweed would have been brought up here on men’s and women’s backs to lighten the soil and to create some kind of workable tilth. At some time in the middle of the eighteenth century, the barn next to the blackhouse was abandoned. Roofless, it became the rubbish heap of the household. Among the bones – of puffin, guillemot, shag, pig, whale, all kinds of fish, cattle, both young and old, and dog – we identified the jaw bone of a horse. Perhaps the ponies, when they finally went, provided a welcome meal.

That is all very well, but I want to take this further, to get some kind of real sensation of what life was like in this blackhouse. Could I recreate the atmosphere within these bare, ruined walls? Could I feel my way to the experience of being a Shiant Islander in the mid-eighteenth century, as the pressure came on, as the world seemed to change around them?

There would, first of all, have been no sense of this building being somehow antiquated. The blackhouse was a modern invention. Medieval houses had been shorter and rounder. This beautiful long form, which nineteenth-century travellers always took for an immensely primitive sort of dwelling, first appeared only in the seventeenth century. It is an ingenious structure. Its low, ground-hugging, rounded shape presents no obstacle to the wind and is both a model and symbol of homeliness. It embraced those that entered it. Its narrow width is governed by the shortage of timber in the isles and its length by the need to shelter more than a family from the weather. It is an occupied farm building rather than a house in which agricultural equipment and animals are also stored. It was always built on a slight slope so that the liquors from the manure heap would run out at the far end, rather than pollute the hearth. On occasions, this slope was ‘so steep that a cask would have rolled from one end to the other’.

The smoke from the central hearth filled the house’s roof and worked as a fungicide to preserve the timbers, which were precious. Meat and fish hung there and were cured in the smoke. Midges, mosquitoes, wood-beetle and other pests were killed off. The sharing of the space with the animals not only provided extra heat in the house, but protected the dung heap and its precious nutrients from the rain, in which its goodness would have been washed away. This arrangement was also healthier than you might think. Lewis had a far lower incidence of tuberculosis than almost anywhere else in the country, a level shared only by dairymaids. It turned out that blackhouses had a sophisticated internal air flow, meaning that heat rising from the cattle and their dung heap carried a weak solution of ammonia (from the urine) across into the human half of the house, where the people breathed it. A weak solution of ammonia, inhaled regularly, is known to prevent TB. Dairymaids were breathing the same air.

If you go into the ruin we have excavated now, the one quality that strikes you above all is its bareness, its lack of detail, the simplicity of structure and form. That is as it should be. These places were never filled or crowded with objects. When the clay floors were first laid, a small flock of a dozen or so sheep were usually folded in there for twelve hours or so to consolidate the floor. The clay is blueish-brown and only turns the red colour we found it when hot ashes are spread across it to warm the floor on which the children sit. There was never much furniture. Alexander Macleod, laird of Harris in the 1780s, ‘made a tour around the whole back part of his extensive estate, and even entered the huts of the tenants, and declared openly that the wigwams of the wild Indians of America were equally good and better furnished.’

The Rev. John Buchanan, a missionary contemporary of Macleod’s, who eventually had to leave Harris in disgrace after seducing two of the local girls, found that

The huts of the oppressed tenants are remarkable naked and open, quite destitute of furnishing, except logs of timber collected from the wrecks of the sea, to sit on about the fire, which is placed in the middle of the house, or upon seats of straw, like foot hassocks stuffed with straw or stubble.

Large stones occasionally served the same purpose. Chairs and stools were rare and tables almost unknown. The men sat on a wooden bench or a plank supported on piles of stone or turf against the wall. The foundations of a bench against the north wall, about six feet long, curving out at one end, is exactly what the excavation found, set a little away from the hearth, which in this house was for some reason moved at one point, about a yard to the north. At night, people would simply take a blanket or a plaid and wrap themselves up in it in the corner. The clay of the floor was warm and the atmosphere in these buildings, as the ethnographer Alexander Fenton has described, was a beautiful thick cloud of homeliness, at the centre of which ‘a fire of peat smouldered with a steady red glow from which rose, not so much smoke, as a smoky shimmer of heat …’. There was no need to shut yourself away from it, at least in the eighteenth century, in a bed. In the morning, the blankets would simply have been folded up. The Reverend Buchanan licked his lips at the prospect of immorality in these conditions: ‘Without separate apartments, we need not be surprised to find the virtue of their women too often severely tried,’ he wrote, ‘and no wonder though the poor unprotected females suffer in such circumstances’. At least, that is what he found.

Although internal walls appeared in the blackhouse during the nineteenth century, at this date there would have been none. The hunger for privacy and for subdivision of living spaces, which had arrived in England in the late Middle Ages, had not yet reached here. This life was shared in almost every detail. The line of big stones that we found across the floor would have been all that separated the upper end of the room from the part preserved for the animals. It was a kerb to the dung heap, nothing more. By early spring, the dung heap would have grown so high that it would have been difficult to get in the door at that end. You would have walked steeply uphill over it before coming downhill again to the hearth. Cows standing in there all winter, along with the goats, sheep, ducks, hens and dogs, would have looked down on the company around the fire with a sweet and beneficent presence. In order to reduce the liquidity of the animal end, the householders ‘attended on their cows with large vessels to throw out the wash’ – or to keep it as mordant for dyes – ‘but still it must be wet and unwholesome.’

A sense of disgust was absent from the intimacy of human and animal in the house. It was lovely to have the cows so nearby. ‘And one luxurious old fellow describes the pleasure he found in hearing the sound of the milk as it squirted into the tub.’ The cows liked the fire as much as people did ‘and particularly the young and tenderest are admitted next to it.’ Besides, the warmth was thought to increase the milk yield.

Warm, shared, busy, an animal fug, perhaps a loom in the corner, sheepskin bags or an old chest in which to store the meal, maybe barrels of potatoes, spades, cas-chroms, rakes, blankets, washing tubs, pots, herring nets, the long, many-hooked fishing lines, perhaps the most valuable things here, each worth seven shillings, against four shillings for a bed or chest, and five shillings for the roof of a small house: all these are described in the inventories at the time. This is something of the feeling of a working blackhouse, an organic whole. It was an ingenious adaptation of limited materials to the comforts of home. It would always have been dark. In the evening, rush lights, burning perhaps in seal oil, more probably in fish oil, boiled off from the fish livers, giving a dark viscous liquid ‘like port wine’, would mean that even on the brightest day, no more than ‘a dim religious light’ would have filled the place. One or two small holes in the thatch would have admitted the light and let out the smoke, although we did find fragments of a window pane buried in the levels above the floor.

The house itself partook of the cycle of the seasons, blackening through the year, glittering sooty stalactites dangling from the roof trusses, becoming ever fuller with the growing dung heap at the animal end. In the spring-time, as the year begins, all of that is removed. The east wall is demolished, the sty cleared out, the roof covering taken away and a sudden wash of light, as much as now floods across the floor of the ruin, enters the building. It starts the year again, cleaned, freshened and ready, as renewed as a dug-over garden, the new turfs and thatch sweet-smelling, a sense of annual optimism to hand.

That yearly pattern had its daily counterpart. Every evening the fire was smothered, ‘smoored’ in the Scots word, to reduce its burning in the night but to keep it alive for the following morning. Alexander Carmichael, the scholar and collector of Gaelic culture in the second half of the nineteenth century, witnessed the plain evening ceremony:

The embers were evenly spread on the hearth … and formed into a circle. The circle is then divided into three equal sections, a small boss being left in the middle. A peat is laid between each section, each peat touching the boss, which forms a common centre. The first peat is laid down in name of the God of Life, the second in name of the God of Peace, the third in name of the God of Grace. The circle is then covered over with ashes sufficient to subdue but not to extinguish the fire, in name of the Three of Light. The heap slightly raised in the centre is called ‘Tula nan Tri’, the Hearth of the Three. When the smooring operation is complete the woman closes her eyes, stretches her hand, and softly intones one of the many formulae current for these occasions.

The only peat on the Shiants is on the heights of Garbh Eilean and the marks of peat-cutting are still obvious on the ground there, as well as the remains of a peat-dryer, a rough stone platform that provided a draught under the stack as well as around and over it, where the newly cut blocks would have been left for a year or so before becoming dry enough to burn.

In the house, the women would sit apart from the men on stumps of driftwood grouped around the fire, while the children crouched between them in the warm ashes strewn on the clay floor. There was no oven in Hebridean culture and all cooking was done either on a griddle or in a cauldron suspended over the hearth. At meals the whole family gathered so closely that a single dish could be shared between them resting on their knees, eating from the common dish either with their own horn spoons, or perhaps with a single spoon handed from one to the next. This dish, three to four feet long, eighteen inches wide, called the clàr, was made of deal, with straw or grass on the bottom; the straw with crumbs of food in it was afterwards given to the cow. The meals – breakfast at eleven o’clock, supper at nightfall – were the times at which the family drew together and were the only occasions in which the door would be shut. Together they would eat the oat or barley-cakes, the potatoes and herring, and the supper of brochan, a kind of gruel; or boiled mutton if they were lucky, or perhaps cuddies in the autumn, caught from the shore in a tarbh net, or cod, dogfish, saithe, skate, eels, pollack, or halibut – to all or any of which milk or cream could be added and for all of which the Shiants were well known, but only if they had managed to get out in the boat. If not, then it was surely to be the dreaded limpets.

As well as the hearths themselves, some hints of this cooking life emerged from the excavation. Tiny fragments of a cauldron: one of its legs and a piece of an iron griddle, with a curved, raised lip on two sides, were found. Small chips of flint from a strike-a-light to make the spark with which the fire – or tobacco: there was the bowl and stem of a clay pipe – could be lit. The flint chips had been brushed to the side of the house and lost in the shadows. There was half a quernstone, cut from the very coarse-grained syenite, the igneous rock which is found only at the far east end of Eilean Mhuire.

It was tucked against the northern wall. Evening and morning, with this hand quern – it was low quality and would have made extremely gritty flour – the women would have ground as much grain as they needed, sieving the flour through sheepskin sieves, onto wooden or pottery plates.

It is the pottery we found that summons most intimately the old life in the house. Over one thousand, four hundred pottery sherds were found in the excavation, dividing quite clearly into two categories. By far the larger, with over one thousand, two hundred pieces, was the so-called craggan ware, the unglazed earthenware, made by hand without a potter’s wheel and fired in the low and variable temperatures of this peat hearth. The Gaelic word craggan is related to the English ‘crock’ and probably comes from the Old Norse krukka. The Gaelic for a can of lager is crogan leanna.

These home-made pots are an archaeologist’s hell. Almost no development can be seen in their style of making, firing or decoration over many millennia. Craggan ware (although the very oldest tends to be finer) has been found on Neolithic sites and it was still being made in Tiree in 1940, although by then only for sale to tourists. The clay for these pots would probably have been dug on Garbh Eilean, as was the clay for the floor, and it was women’s work to make these pots. You can see their thumb marks on the clay, pushing at it, folding out the rim, and the places where the unbaked pot was set to rest on the grass, which left its slight impressions on the body. Here and there, very rarely, a piece is decorated with a few slashed lines or with scattered points, where a straw has been jabbed into the clay. Perhaps these are just the work of a bored child, fiddling with the pots her mother was making, playing with the clay when still soft.

There is a symbolic network woven around the craggan, bringing together women, milk, cattle, clay and the hearth. Only women can make the craggan, just as only men can go out in the boat and just as women make butter and cheese in the churn, or in the sheepskin which does for a churn in poorer families. The opening at the craggan’s neck, it was said, must be large enough for a woman’s hand but too small for the muzzle of a calf. The body of the pot would have been roughly rounded, as high as it was wide, and in various sizes, some big enough to milk into, others little more than a container for butter or curds. Roundedness was important. Although there is one dish, like a sugar dish, probably copied from an import, which is completely flat-bottomed, not a single Shiant craggan pot has a flat base. The pot itself is like a small womb, but made of clay, and so perhaps like a small house.

Unroundedness, even if convenient, would have spoiled it symbolically. Houses too were made with rounded corners. Milk taken straight from the cow into one of these little craggans, which had been warmed by the fire, was called ‘milk without wind’ and was a cure for consumption. A piece of calfskin or lambskin was used to cover the pot and was tied there with a cord beneath the out-turned rim.

Arthur Mitchell saw a woman making craggans on Lewis in 1863. This would have been the scene in the Shiant house, or perhaps outside its south door, on a bench there, on a warm day in summer, the headscarf down around her neck, her eyes half closed against the sun, her children at her feet and the lark above her, looking out to the distant mountains of Skye.

The clay she used underwent no careful or special preparation. She chose the best she could get and picked out of it the larger stones, leaving sand and the finer gravel which it contained. With her hands alone she gave the clay its desired shape. She had no aid from anything of the nature of a potter’s wheel. In making the smaller craggans, with narrow necks, she used a stick with a curve on it to give form to the inside. All that her fingers could reach was done by them. Having shaped the craggan, she let it stand for a day to let it dry, then took it to the fire in the centre of the floor of her hut, filled it with burning peats, and built burning peats all around it. When sufficiently baked she withdrew it from the fire, emptied the ashes out, and then poured into it and over it about a pint of milk, in order to make it less porous.

The other ceramic pieces we found might as well have come from the other end of the world. Alongside these Stone Age, hand-made and, to be honest not very well made things (many of the craggan pieces were never fired to a high-enough temperature and crumble at the touch), are a few shards of elegant eighteenth-century tableware, and the moulded white china lion’s leg of what might have been a sugar bowl.

I asked the ceramic historian David Barker, Keeper of Archaeology at The Potteries Museum in Stoke-on-Trent, to have a look at the sherds. Did they fit the dates of the documents? Four of them did. There were four diagnostic sherds from the 1760s, moulded creamware; what Dr Barker called ‘reasonably upmarket lead-glazed earthenware and white salt-glazed stoneware, including the base sherd of a tea-pot of quite high status.’ The pottery almost certainly came from Staffordshire, perhaps from Liverpool. After them, there was nothing in the collection I had given him until the 1820s and ’30s, when there were a few pieces of Scottish earthernware from potteries on the Clyde. The house may have been re-occupied for a while by visiting shepherds in the nineteenth century, but the fifty-year gap before them confirmed exactly what the papers had suggested: the old Shiant life came to an end in about 1770.

These pieces are, of course, a sign of the market: tradable objects, the new system of things, of money in circulation, of the world outside the islands. An annual July market was held in Stornoway every year, to which the Shiant Islanders might have gone with their own wares to sell: puffin feathers for pillows, perhaps some cheese, wool dyed with the lichen and woven into tweed, or knitted into socks and jerseys. It is likely that some traveller had pieces for sale at the market from the huge factories to the south. It isn’t difficult to imagine how beautiful their colours would have seemed to anyone accustomed to the dun and orange-tinged ordinariness of the craggans.

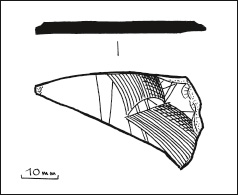

The Stornoway market is a possibility, but one fragment of Shiant ceramic in particular hints at another source. It is a small piece, an inch and a half long by three-quarters wide, of a large dinner plate made in white salt-glazed stoneware.

In the clear glaze, somebody quite carefully has scratched a picture of a sailing ship. No more than one or two bellied-out sails, a couple of shrouds and some ratlines are visible in the fragment, but in the care of the work, and its double expertise – the man knows both the workings of a ship’s rigging and how to engrave in a difficult, slippery medium – there are signs here that the Shiants in some way or other had contact with a deep-sea sailor. This, in effect, is scrimshaw work, which the whalers usually carved on bone and tusk, rather than plates, catering for a sophisticated urban market which valued the primitive material. But whalebone was a common material here.

We found a spatula or scraper made out of it in the byre midden, and it would be less attractive for a Shiant Islander than the glamorous, new and expensive kind of china just then becoming available. Is it possible that this plate was brought back to the Shiants, perhaps to a mother, by a son who had left to find work at sea, as life at home seemed to become both constrained and difficult? Is this, in other words, by the hand of a Shiant emigrant, one of the first of the forty-odd inhabitants to leave the world of self-sufficiency for the world of money before the general rush began?

That meeting of porcelain and craggan, of the blue fronds and the thumb-whorls, of the sheeny modern glaze and the chthonic realities of the clay, recurs again and again in the objects we found in the house. There were parts, incredible as it might sound, of a wineglass, as well as many green bottle pieces. There were some scissors and a thimble (machine-made, copper alloy), a leather button and a copper one. Mixed up with them were objects from the other side of the divide: several stone tools and a stone garden hoe, made from Shiant dolerite, polished on most sides, carefully chipped at its point, perhaps from a site halfway between the blackhouse and the landing beach, where there is some evidence of stoneworking on the hillside.

Some tools and wineglasses: these are the sharp edges of a world in transition. The kind of war which that disjunction can generate, between ancient and modern, between local and national or supranational, between the antiquated and the technological, suddenly and momentarily erupted into the Shiant Islanders’ lives. Thursday, 29 May 1746 is the only point at which a grander history touched the islands even a passing blow. Bonnie Prince Charlie is on the run and the Minch is thick with naval vessels on the look-out for him. At one point, watchers from the Lewis shore can see fifteen warships spread across the horizon.

One of them is HMS Triton, a new frigate, less than a year old, a fast ship, built for observation and pursuit, under the command of William Brett, recently promoted Commander. His log is in the Public Record Office. It was known that the Young Pretender was looking for a ship back to France and the Triton’s cruise, up from Sheerness in Kent, around the northern capes and down into the Hebrides, consisted of one arrest after another: a hoy from Flamborough bound for St Malo, a Danish ketch en route from Stavanger to London, a Norwegian sloop carrying lobsters to the English markets, several Dutch fishermen, a snow (from the Dutch snaw, meaning a small vessel like a brig) from Aberdeen carrying hay to the army at Cromarty, a ship from Virginia bringing tobacco to Hull, a schooner bound to Madeira from Rotterdam and another snow from Lancaster heading for Riga. You could scarcely ask for a more vivid demonstration of the surge of new business in the eighteenth-century seas.

Early on the morning of 29 May, with a slight wind coming out of the north, the Triton was four miles or so south of the Shiants when she spotted a sail to the north of her in the faintest of dawn light. Brett ordered the Triton to give chase. The other ship turned and beat towards the Shiants. Like all naval action in the days of sail, everything happened in slow motion. Only at seven o’clock was the Triton near enough to fire warning shots, which they did, several of them, ‘but ye chase would not bring to.’

By now the other vessel was in the bay between the three islands and at half past seven that morning Brett from his quarterdeck could see ‘a boat full of men go on Shore from her … The Boat Return’d with two men which was again filled but our shots now Reaching them they got into ye vessel again.’

Although the ship was attempting to make good its escape to the north, Brett now had them pinned against the Garbh Eilean shore. The puffins would have been wheeling above them, startled into flight by the Triton’s warning guns. Clearly, in the islands where the Pretender was undoubtedly still on the run, this was most suspicious behaviour. Had he stumbled on the fugitive himself?

At eight o’clock in the morning the Triton came up with its quarry ‘and she brought too with her head off Shore and hoisted English Colours. Ditto. Saw their men Rang’d at their Quarters She having fourteen Guns.’ It looked for a moment as if a duel was about to take place but the terrifying sight bearing down on them of a fully armed and crewed man-of-war (the Triton carried between twenty and thirty guns and a complement of a hundred and thirty) brought a different outcome and a strange story:

The Mate came on Board and Inform’d us She was a Snow from Dublin bound to Virginia with Bale Goods som Powder and Shot 81 Men & 26 Women Indentured Servants when on ye 13 Instant Being a Hundred Leagues to ye Westward of Ireland ye Servants had rose and Seiz’d the Vessel and order’d her to be Steer’d for ye Ile of Sky in order to make a prize of her & join the Pretender’s Son, that 9 of them with 3 women had gone on Shore in the Boats.

Brett took the rest of the mutineers, and the snow’s crew, on board the Triton. He put his own men on the snow, the Gordon as it was called, and took her in tow. He would eventually deliver them to Carrickfergus Jail in Ireland.

But what of the twelve Jacobites who had landed on the Shiants? The next day Brett sent a boat ashore on Scalpay to ‘Acquaint the Magistrate of those Rebells which had landed with Arms in order for his Apprehending them.’ The naval officer would have been unaware of the irony. Bonnie Prince Charlie had passed this way twice in recent weeks, once only nineteen days earlier, skulking at night in an open boat down the Lewis and Harris shores, running from the hunt that was on for him in the north of the island, and once previously at the very end of April. A shipwrecked Orcadian, giving his name as Sinclair, had landed on Scalpay and had been taken in by the magistrate and tacksman, Donald Campbell. Sinclair rescued a cow from a bog and went fishing in the Minch with Campbell’s son before anyone realised he was the Young Pretender. News got out and the pro-government and fearsomely anti-Catholic minister of Harris, the Rev. Aulay MacAulay (the historian’s great-grandfather) arrived with a posse to arrest the Prince. Campbell would have none of it and shielded the Prince while he escaped. For many years an inscription on Campbell’s house in Scalpay (or at least a later house on the same site) recorded it as the place where Prince Charlie had stayed ‘when he was wandering as an exile in his own legitimate Kingdom.’ You won’t find it there now: the house became a Presbyterian manse and the Jacobite inscription was harled over. One thing is certain: Campbell would not have pursued the Irish Jacobite rebels on the Shiants too hotly. The Shiant population, if they were still Mackenzies, or still attached to the Mackenzies, might well have had Jacobite sympathies themselves. They might have thought, with a Catholic king returned to the throne, that the sterilising Presbyterianism of the Church would have been removed from their necks. The holy stone might have been recovered from beneath the floor. They might have entertained the rebels in this very house, perhaps even able to communicate in Irish and Gaelic, to tell the stories and sing the songs which their shared tradition had preserved. There is no saying: after the Triton leaves, the Irish rebels disappear from history and the normality of Shiant life closes back over them like the tide above a rock.

Lying awake one summer night in Compton Mackenzie’s house, with the dogs on the bed beside me, and the sky outside already half light, I abruptly realised with middle-of-the-night clarity something about the other house we were so carefully excavating up the hill. The presence of wineglasses, winebottles, sugar bowls, a teapot, a thimble, scissors, a Bible: these were not the belongings of a peasant’s house. This was the house of a sophisticated family. I had often in previous years gone to look at it, full of nettles and with a hint of rats in the little cupboard at the corner and in the holes in the walls. I had always seen it as a primitive, roofless shed. Now, though, quite suddenly, I saw it for what it was: this was the tacksman’s house. These were his belongings we were finding, broken, brushed to the shadowy corners of the room. This was the house of the last man to live on the Shiants who thought of them as profoundly his, connected to him not by contract but by a deep sense of identity with the land itself. Tacksmen were named after the property they held and this man would have been known as ‘Shiant’. Here in our hands were the last flickers of a form of possession which stretched back to the Vikings and which predated any modern understanding of land as a market commodity. We were touching the outer edges of an ancient past at the very moment it was coming to an end.