12

AS I WALK ACROSS the Shiants today, along the path which the black cattle would have taken from the byres by the shore to the high grazings, with the meadow grass and the tiny bilberry bushes brushing at my boots; past the abandoned lazybeds to the cluster of little houses in the central valley; up past the rush-filled kilnhouse, identified by Pat Foster, where the barley and oats sodden in autumn rains might have been half-dried before storage and threshing; and as I stand in the cleared floor of the house we excavated, so radically roofless now, so exposed to the cold and the wet, I feel a vicarious nostalgia for the wholeness which is now absent here.

The walls of a blackhouse are four feet thick. It was always said that if you wanted to build one (a task for the community together) you had to collect the amount of stone you thought necessary and triple it. If it is true to say that you can’t remember time, only the places in which time occurred, then I think you could say that the bulk of these enormous walls is a kind of time sponge, deeply absorbent of the moment passing, sucking up lives as they happened, holding events as if in a vast memory bank. Standing in the house after the archaeologists had left, and listening to the lark still singing above me, I could feel that these stones, and by extension these islands, continue to hold the memories of the life that was lived in them a quarter of a millennium ago.

Perhaps it is more of a desire than a sensation, a wish to feel that the memories remain. Certainly it is an appetite that needs feeding. What was the colour and smell of the ancient Shiant normality? How did the people who lived here behave towards each other, how rich was their life in more than the material sense? How good was existence here in the mid-eighteenth century? One or two memoirs can do something to people the ruins. The Rev. John Buchanan, the lustful missionary, found the people in Harris, as one might expect, divided between courtesy and suspicion. ‘They address one another by the title of gentleman or lady and embrace one another most cordially, with bonnets off,’ he wrote. ‘And they are never known to enter a door without blessing the house and people so loud as to be heard, and embracing every man and woman belonging to the family. They both give and receive news, and are commonly entertained with the best fare their entertainers are able to afford.’

‘Neighbour’ was the common term of affection and endearment. The essence of life was shared, as much for practical as for moral reasons. The pattern of land-holding, at least below the level of the tacksman, consisted of two concentric circles: the family and its homestead, with its own walled vegetable patch or kailyard, its own animals, its own family tools, a spade, other simple cultivating tools and a distaff for spinning. Outside that, by the eighteenth century anyway, was the joint farm, which would include the neighbouring waters, and for the working of which a jointly owned plough and boat would have been needed. Each of the five Shiant families would have a right to an equal share in the commonly held arable ground and farmed ridges. The operation of both boat and plough would depend on team work. A boat would need five men to launch it, four to row and one to steer and in Gaelic there is a separate system of numbers to describe teams rather than a collection of individuals.

A place like this, where nothing can be given and little risked, where anything eccentric or not done before is likely to be condemned or despised, is the landscape of received wisdom. There is a saying for every occasion, a nodule of deeply conservative and hard-won understanding. And there is a Gaelic proverb for this: ‘No one is strong without a threesome / and, with a foursome, at best they’ll be limping.’

A plough would need at least three men; one to lead the horse, one to hold the plough and one to turn the sod neatly over after they had passed. But four ponies would be required and each man would have had only one or two. Life was unsustainable alone.

It was far from being a communist system. Private property was fiercely protected, but an equal share of rent, an equal number of stock on the common grazings, an equal quantity of arable land and equal commitment to the work were the essential conditions without which these island communities could not have operated. It would have been impossible to pull up or launch the boat, handle the sheep or dig the ground without your neighbours. I have sweated alone on these islands for hours on these tasks, longing for nothing more than a helping hand, surveying the length of the undug lazybed like a pile of last week’s washing up; despairing of the possibility of ever pulling the dinghy above the tide; finally flummoxed by the impossibilities of catching on your own a lamb whose leg had somehow been cut and was bleeding. Work done in common is more than efficient; it is a source of pleasure, stimulation and happiness. When my friends Patrick Holden and Becky Hiscock came around the bay from the house to help me dig the heavy, uncooperative sods of the lazybed which I was attempting to cultivate, it was honestly as if the sun had come out. Alone nothing, together everything: that is one of the governing facts.

For the Reverend Buchanan, with the idea of individual salvation and private guilt in his mind, all of that community talk seemed to be something of a veneer over a harsher reality. Everyone would keep the head of a sheep he had killed for four or five days after he had done so. The head carried the ears and the ears carried the marks which identified the owner. Only with a head could a man prove a carcass was his own. And the old were given scant respect: ‘When a man becomes so frail as not to be in a capacity to look after his flock of sheep in person, he is very rapidly stript of them, and that frequently by his near relations.’

One has to wait for a nineteenth-century account of popular culture in the Isles for life to be seen here in a sympathetic light. Alexander Carmichael, without whose tireless collecting over decades towards the end of the nineteenth century, half the Gaelic cultural landscape would be missing, wrote the following passage in the introduction to his monumental Carmina Gadelica, or ‘Gaelic Songs’, intermittently published between 1899 and the 1970s. It is worth quoting at length because it gives a more affectionate and richer portrait of life in such a house as the Shiant blackhouse than any that has ever been written. The people of the Outer Hebrides, Carmichael wrote,

are good to the poor, kind to the stranger, and courteous to all. During all the years that I lived and travelled among them, night and day, I never met with incivility, never with rudeness, never with vulgarity, never with aught but courtesy. I never entered a house without the inmates offering me food or apologising for their want of it. I never was asked for charity in the West, a striking contrast to my experience in England, where I was frequently asked for food, for drink, for money, and that by persons whose incomes would have been wealth to the poor men and women of the West.

That is precisely the experience that I continue to have in these islands. Time after time, at the door of Donald and Rachel MacSween in Scalpay, I have turned up filthy and stinking from weeks on the Shiants, and time after time they have housed me, washed me, washed my clothes, fed me, driven me here and there, and looked after me, my boat and my belongings in a way which is scarcely conceivable in any other part of Britain. That much of the old culture remains but Carmichael was travelling early enough to see the blackhouse, and in particular the tigh cèilidh, the party house, still functioning in the way it was intended to:

The house of the story-teller is already full, and it is difficult to get inside and away from the cold wind and soft sleet without. But with that politeness native to the people, the stranger is pressed to come forward and occupy the seat vacated for him beside the houseman. The house is roomy and clean, if homely, with its bright peat fire in the middle of the floor. There are many present – men and women, boys and girls. All the women are seated, and most of the men. Girls are crouched between the knees of fathers or brothers or friends, while boys are perched wherever – boy-like – they can climb. The houseman is twisting twigs of heather into ropes to hold down thatch, a neighbour crofter is twining quicken roots into cords to tie cows, while another is plaiting bent grass into baskets to hold meal.

Ith aran, sniamh muran,

Is bi thu am bliadhn mar bha thu’n uraidh.

Eat bread and twist bent,

And this year you shall be as you were last.

The housewife is spinning, a daughter is carding, another daughter is teazing, while a third daughter, supposed to be working, is away in the background conversing in low whispers with the son of a neighbouring crofter. Neighbour wives and neighbour daughters are knitting, sewing, or embroidering. The conversation is general: the local news, the weather, the price of cattle, these leading up to higher themes – the clearing of the glens (a sore subject), the war, the parliament, the effects of the sun upon the earth and the moon upon the tides. The speaker is eagerly listened to, and is urged to tell more. But he pleads that he came to hear and not to speak, saying:-

A chiad sgial air fear an taighe,

Sgial gu la air an aoidh.

The first story from the host,

Story till day from the guest.

The stranger asks the houseman to tell a story, and after a pause the man complies. The tale is full of incident, action, and pathos. It is told simply yet graphically, and at times dramatically – compelling the undivided attention of the listener. At the pathetic scenes and distressful events the bosoms of the women may be seen to heave and their silent tears to fall. Truth overcomes craft, skill conquers strength, and bravery is rewarded. Occasionally a momentary excitement occurs when heat and sleep overpower a boy and he tumbles down among the people below, to be trounced out and sent home. When the story is ended it is discussed and commented upon, and the different characters praised or blamed according to their merits and the views of the critics.

If not late, proverbs, riddles, conundrums, and songs follow. Some of the tales, however, are long, occupying a night or even several nights in recital. ‘Sgeul Coise Cein’, the story of the foot of Cian, for example, was in twenty-four parts, each part occupying a night in telling.

That beautiful nineteenth-century account of a disappearing culture, its warmth and coherence, its sense of shared life, of a vital communality, is of course what many Victorians longed for and pined after, from Disraeli to Ruskin and Marx. But if Carmichael describes it with love, he does so in a way that animates the Shiants. If anyone ever visits the ruined blackhouse here, those are the words he should have in mind.

The air of approaching crisis steepens after the middle of the century. The Seaforths, like many Highland landlords, were short of money. Rents had not been keeping pace with expenditure and the tacksmen, to whom the best parts of the estate were let out, were not attuned to the realities of the new financial world. In the middle of the eighteenth century, the old Seaforth tacks, the Shiants among them, were relet for higher rents to new men. The islands were now let to the highest bidder. In 1766, the Shiants were let out to Donald MacNeill for £7 10s (a steep increase from about £4 9s in the 1720s). In 1773 they were let to George Gillanders, Seaforth’s own Chamberlain of Lewis, for £9 and in 1776 to a Kenneth Morrison for £10 15s. Just how this increased rent – more than double in fifty years – was raised from the Shiants is not clear, nor is it known what happened to the departing tacksman himself. Many left for the New World, and the tacksman here, named like all of them after the territory he held, a man known as ‘Shiant’, might have been among them.

In the wake of his departure, there are signs of real strain and breakdown of long-established customs. It was a process witnessed by Dr Johnson in Skye in 1773, and to his romantic Jacobite Tory sympathies, it looked like a social and cultural disaster. ‘If the Tacksmen be banished,’ Johnson asked,

who will be left to impart knowledge, or impress civility? Hope and emulation will be utterly extinguished; and as all must obey the call of immediate necessity, nothing that requires extensive views, or provides for distant consequences will ever be performed. As the mind must govern the hands, so in every society the man of intelligence must direct the man of labour. If the Tacksmen be taken away, the Hebrides must in their present state be given up to grossness and ignorance.

Signs of that cultural breakdown became apparent on the Shiants. On 26 September 1769, Dr John Mackenzie, Seaforth’s commissioner at Brahan Castle near Dingwall on the east coast, wrote to George Gillanders, the estate chamberlain on Lewis. They were friends. Mackenzie’s brother had been Gillanders’s predecessor and Mackenzie had got Gillanders the job:

D[ea]r George,

It is now some time since I wrote to you or heard from you and I dare say you’le very soon be thinking of coming to the main land and I hope with the rents in your possession which I can assure you are much wanted by the owner and all his conections.

Immediately upon receiving yours about the wreck of a ship upon the rocks of Shant I wrote to Lord Stonefield and Mr Davidson [Edinburgh judge and lawyer respectively] requiring their advice for your direction in prosecuting those guilty of plundering the ship but unluckily they were both out of Town at some distance so that it must be some time before we can get any advice of theirs on the subject. I doubt not however that you have taken all the care possible in taking a precognition [a series of witness statements] so as to fix guilt upon the barbarous actors of the Robbery and if you have got that done I dare say your commission as substitute admiral [a power to act on behalf of the crown in anything to do with the sea] will enable you to prosecute the delinquents either on the spot or by sending them prisoners to be tryed by some other Court of Justice, in short no pains must be spared in bringing them to punishment and I beg you may come sufficiently prepared for that purpose.

Here the letter is torn, but it resumes:

…as we never had more need of Cash. my Compts to Peggy and to the rest of your family. I hope she keeps her health

I am your etc

John Mackenzie

Unfortunately neither Gillanders’s earlier letter to Mackenzie nor anything describing the outcome of the case seems to have survived, but evidence of stress crowds in. The growing population and the shortage of land was leading to breakdown of family relations. On Lewis, children were turning their parents out of the shared home, setting them ‘loose upon the world and a begging, and will not give them any sort of subsistence’, as Gillanders described it in March 1768. His solution – and he is a sympathetic figure: a modern manager trying to deal with an intractable situation – was not to allow any tenant of the estate to take in their son and daughter when married nor to subdivide their properties in any way, on pain of eviction.

Gillanders was busy with the kelp business. Since the late seventeenth century it had been known that the seaweed, whose alkalinity had always been used to sweeten the islands’ acid soils, could be burnt and the sticky soup that resulted would solidify into a solid mass which was easily transported, and from which both soda and potash could be extracted. As these chemicals were vital in the making of soap and glass, and were needed to bleach linen, there was a prospect here, for the landlords, of good money.

The long, dirty and exhausting extraction process would be undertaken in June and August. The kelp was piled into large, often stone-lined trenches. Pat Foster identified one on the north shore of Garbh Eilean, a slightly ramshackle arrangement of stones almost indistinguishable from the mass of other fallen rock in the area.

It is next to the bay where the kelp still grows thick and dense, with tiny beadlet anemones clinging to the dark brown blades and where, at low water springs on a sunny day, the mass of weed winks and glitters like a plate of eels in the stirring of the swell. Just here, in William Daniell’s prints, from sketches made as late as 1815, a skein of smoke drifts from the kiln towards the horizon, and small boats are gathered to take the burnt residue to the Lewis shore.

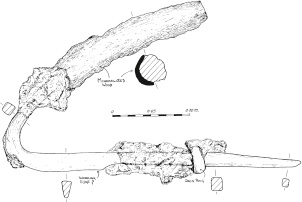

The kelp was burned for four to eight hours, the fire kept going with heather and hay. The women would often have the job of watching it, adjusting the heat to keep it alive all day without wasting the precious fuel. The men with long-handled iron spikes or hooks would stir the heavy mass to ensure an even burning of the weed. Not a single one of these ‘kelp irons’ had ever been discovered, but we found a pair in the excavation of the blackhouse.

One is a heavy iron spike, two feet long, with a socket at one end into which the shaft of a long wooden handle could be fitted. The other is sharply hooked, pointed at one end and with mineralised wood clinging to it, remnants of a handle which would once have been much longer. A ring is rusted to the spike, but no one yet has been able to explain its purpose. After the mass of kelp had been thoroughly melted, the pyre would be covered with turf and stones to prevent it getting wet and then left overnight. The following morning the spikes could be used again to break the glassy agglomeration into lumps that could be carried to the boats.

Why these useful tools should have been left here is a curiosity. And I have been unable to find any documents relating to Shiant kelp. Thick lumps of paper survive in the Seaforth records detailing the arrangements which Gillanders was making for his proprietor, sending surveyors out to estimate the volume of the seaweed in different parts of the Lewis shore, arranging for ships to be piloted into the tricky sea-lochs on both east and west coasts of the island, sending Lewis kelpers to work on the Seaforth estates in Kintail, paying for the kelp which was to be sold in Liverpool, Whitby and Dublin with oatmeal, bearmeal (the flour of bere barley) and by remission of rent.

Huge amounts were made – 89 tons 9½ cwt from the parish of Lochs alone, baked and delivered to the waiting ships in the summer of 1770. There are receipts from the captains preserved in the Edinburgh records, still tied together with a piece of brown wool and thumb marks on the paper from what must have been a filthy cargo. But no mention of the Shiants. The only possibility is the strangely large quantity of kelp collected from Donald McKenzie at Valamus just across the Sound in Pairc, 6 tons 12 cwt for 1770 alone. Other shoreside settlements rarely produced more than a ton each. The Valamus return may include kelp transshipped from the Shiants.

The kelp business is another note in the Shiants’ death knell. As the kelp went into the heritable proprietor’s kilns, it could not be applied to the fields. A desperate shortage of fertility was inevitable; hunger accompanied the work. James Hunter, the historian of crofting, quotes William MacGillivray from the 1830s. The conditions would have been similar here half a century earlier:

If one figures to himself a man, and one or more of his children, engaged from morning to night in cutting, drying, and otherwise preparing the sea weeds … in a remote island; often for hours together wet to his knees and elbows; living upon oatmeal and water with occasionally fish, limpets, and crabs; sleeping on the damp floor of a wretched hut; and with no other fuel than twigs or heath; he will perceive that this manufacture is none of the most agreeable.

‘The meagre looks and feeble bodies of the belaboured creatures,’ the Reverend Buchanan wrote, ‘without the necessary hours of sleep, and all over in dirty ragged clothes, would melt any but a tyrant into compassion.’ It is from MacGillivray’s account that one word glares out: limpets. They are here by the Eilean an Tighe house in abundance. Limpets, about a quarter of a million of them, are piled in and over the walls of the ruined barn. There must have piles like this all over the Hebrides. Dr Johnson saw them: ‘They heap sea shells upon the dunghill, which in time moulder into a fertilising substance.’ We dug at them for day after day. Using the same maths as before, but imagining a bigger family, perhaps eight of them, this second limpet deposit represents about fifteen hundred limpet meals, or fifteen years of hunger. The figures can only be approximate, but the size of the limpet pile is articulate enough, fifteen feet long, six wide and four high, a ziggurat of strain and sorrow.

As we excavated the limpet midden, you would come across clusters of shells that had clearly been dumped there in a single throw, the shells still nested into each other, chucked from the pot onto the heap. The thickness of the pile diminished from east to west: whoever had taken the meat out of the limpets had done so in the house, had walked out of the door, around the east end on the roughly paved platform, and chucked the contents over the ruined barn wall. Here and there was a clot of fishbones, or in one place five puffin heads still lumped together from a single stew. Elsewhere, the heap was widely and deeply disturbed: dogs, chickens and perhaps children had picked it over and stirred it up even as it accumulated. Many of the bones seem to have been drilled for the marrow and others look chewed, either by men or by dogs. Drilling for marrow is a sign of hunger, of squeezing out every last drop. The archaeologists could find no layering, no diagnostic stratigraphy, in the heap. The limpets were muddled together with every other bone. But the meaning was clear: life on the edge.

The picture is graphic enough: the landlord requires a higher return from his estate as a whole; at the same time the number of people on the Shiants rises; the islands are let to new men at higher rents and the place is squeezed agriculturally, both to pay that rent and to feed those people; it is a desperate time and from the 1760s onwards the population drops through emigration; kelp manufacture turns the islands towards the production of a global commodity; that lasts for a few years and then the population collapses, leaving a single family tending the cattle. The map-makers working for the Ordnance Survey in 1851 noted a few ruins and heard from their informant Neil Nicolson of Stemreway that ‘the islands were formerly occupied by Five families (about Eighty years ago) who it is said procured a comfortable subsistence by their produce, and the fish which is found in great abundance around their Coasts.’ That gives a date of about 1770 for the crucial departure. Why do they leave? Because kelpers can be brought in seasonally and the rent is more easily paid by abandoning any attempt at arable farming here and turning the place into a giant pasture. A single employed family is needed where a community had existed before.

By the last quarter of the eighteenth century, the entire way of life which places like the Shiants had supported was looking out of date, unenlightened and doomed. The economist, James Anderson, follower of Adam Smith, friend of Pitt’s, in his An Account of the present state of the Hebrides, published in 1785, voiced the Establishment view.

In the Hebrides, unless it be at Stornoway in Lewis, and Bowmore in Islay, there is not perhaps a place without the Mull of Cantire, where there are a dozen of houses together: – very few indeed are found but in scattered hamlets only.

We ought not to be surprised at the poverty of the people in those regions, nor at the indolence imputed to them. They are indeed industrious; but that industry is unavailing. – They make great exertions, but these exertions tend not to remove their poverty. Is it a wonder if, in these circumstances, they should sometimes think of moving to happier abodes?

In consequence of this general system of dispersion that prevails in all those regions, the proprietors find their lands overstocked with people who are mere cumberers of the soil, eat up its produce, and prevent its improvement, without being able to afford a rent nearly adequate to that which should be afforded for the same produce, were their fields under proper management.

All the strain that is evident in the Shiants, the cutting of new fields out of the unproductive moor, the pressure of the increasing rents, the crowding of people in the houses, the desperation of those who had to survive on limpets, the robbing of the wreck, the back-breaking strain of gathering and burning the kelp for benefits which seemed to accrue more to the landlord than to those who were doing the work, all of that is reduced to the grim phrase: ‘mere cumberers of the soil’. Even now, at this distance, can anyone not feel indignant at the description? I feel like taking the shade of James Anderson (living in Edinburgh, dying in Essex, existing, I guess, somewhere in Purgatory), showing him the limpet pile and asking him what he might make of that. Did he not grasp the reality of what that pile represented, nor imagine what that life might have been like?

No one now would tolerate living on the Shiants. People had come to understand the virtues of concentration, of agglomeration, of the division of labour, and none of those things were possible stuck out on the Shiants, where a man was forced to be his own ploughman, labourer, tanner, mason, shipmaster and butcher. The emptying of places like the Shiants was the product of a profound change in the nature of economic life, in which the local is subsumed in a much larger system. Nowadays, it would be called globalisation.

The Shiants died. There are the faintest traces in people’s memories of who these departing Shiant Islanders might have been. Hughie MacSween, who had heard it from his uncle Malcolm or Calum MacSween, thought a man called Hector, Eachann, had lived at the south end of Eilean an Tighe. And, even more remotely, a whisper on the ether, a woman in Toronto, Allana Maclean, has posted on the Internet her own family tradition that her great-great-grandparents, Donald MacDonald and Janet McKinnon, or more possibly the parents of one or other of these, at some time in the last decades of the eighteenth century left the Shiants for Skye. But that tells you little. They are nothing more than names attached to absences.

The Shiantachs left not because people like James Anderson willed it – there is no evidence of a Shiant clearance in the classic sense – but because life was no longer tenable there, largely because the expectations of land and its productivity had risen. Human life on the Shiants had been founded on cyclicality, a kind of stasis in which each year, with luck, would be no worse than the one before. That is the meaning of the saying recorded by Alexander Carmichael: ‘Eat bread and twist bent, / And this year you shall be as you were last.’

But the idea of working capital, trade, expansion of markets; above all of growth, and an expectation of growth, of increasing demands, increasing expenditure, increasing comfort and increasing wealth, cannot be accommodated in such a system. For the capitalist, every year is a failure unless it is an improvement on the one before. For a while, places like the Shiants reacted. The population increased, the attempts were made to get a commercial crop of kelp, but the ceiling was soon reached and the new life could not be sustained here. The Shiants now became, for the first time, a back room, a place in which animals could be grazed, and where people were perhaps needed to look after them, but not really a scene for human habitation. The new society had to retreat from places in which the old had felt at home. Insularity was now a symptom of backwardness and isolation a kind of failure.

It was not a new process. People had been draining out of the farthest Hebrides for generations. In 1549, there were forty-two inhabited islands attached to Harris and Lewis. By 1764 that had sunk to sixteen. In 1841 there were still sixteen (although not the same ones: some fertile islands such as Pabbay in the Sound of Harris had been cleared; others, much less suitable, reoccupied by the land-hungry). More than a hundred Hebridean islands have been abandoned since 1549, but most of them were deserted between 1549 and 1764. It is a sign of how rich a place the Shiants were that, despite their distance from any other shore, and despite the ferocity and difficulty of the seas around them, the people should have gone only after most other islands had been left.

There is a chance, although I think it unlikely, that the people were evicted from here. In the spring of 1796, the Seaforth estate cleared a large number of people off many townships across Lewis, a total of five hundred and seven tenants and thirty-one tacksmen. The sheriff officers were paid fivepence a mile (measured one way only from Stornoway); their assistants fourpence a mile, to travel out to the townships and give the news. It was considered important that ‘the subtenants should also receive a verbal notice each from the Ground Officer.’ The documents are sobering enough, name after name written out in the clerk’s slightly shaky copperplate hand, all of them, as the writ for 22 March 1796 puts it,

to hear and see themselves decerned & ordained by Decrees and Sentence of Court to flit and remove themselves their Wives Bairns Familys Servants Subtenants Coaters & dependants and all and sundry their Goods and Gear forth & from their pretended Possessions above mentioned and to leave the same void Redd and patent at the term of Whitsunday being the fifteenth of May next to come, to the end the Pursuer by himself or servants may enter thereto Sett use and dispose thereof at pleasure in all time coming.

One of the tacksmen named in these 1796 Summons of Removing is ‘Murdoch Macleod, shipmaster in Stornoway, Tacksman of Limerbay and Shant Isles’. Is it possible, then, to think of the Ground Officers arriving here with their written summons, bringing them into house after house, first by the shore, then up to the middle valley, following the cow path between them, ducking into the low doors of the houses, showing the people the names of ‘Murdoch Macleod’ and of ‘Shant Isles’ (everyday Gaelic in the 1790s already had a leavening of English and the inhabitants of the Shiants were not necessarily illiterate: remember the Bible binding on the house floor) and giving them the verbal notice, eight weeks, until Whitsun, to leave, just as the puffins were coming in, just as the manure was to be spread on the fields, just as the year was to begin again?

It is possible, but I don’t think anything so dramatic happened here. When also in 1796 the Reverend Simson describes this most outlying part of his parish, he implies that there has been only one family here for a while. That cannot mean the place had just been cleared. The Summons of Removing, or Warning Away Notice, can be explained as a bureaucratic mechanism by which the terms of Macleod’s lease were changed, or by which the landlord gave it to someone else at a higher rent. It was a sign of something already being at an end, not the instrument by which it was ended.

The roofs of the abandoned houses fell in. The archaeologists found, just beneath the modern turf, the thick residue of the collapsed roof lying directly on the ash and charcoal of the abandoned floor, an earthy layer, rummaged about in by the rats. In amongst the rotted turf and thatch were thirty-four iron boat strake rivets. The house must have had a piece of a boat patching the roof. (Freyja would produce thirty-four rivets from a section of her hull three feet deep and seven long.) Inevitably, in a place where timber was so short, a washed-up boat, perhaps part of the wreck they had been plundering in 1769, would have been put to good use.

It was this hunger for timber – a constant in the Hebrides, but everything is heightened at this time – which lay behind the most shocking of all the stories associated with Shiants. I took Freyja across to the scene of the Pairc Murders one evening, a calm and beautiful journey, with the mountains of the mainland opalescent in the evening sun, and lenticular clouds, as smooth as sucked sweets, hanging over the hills of Lewis. The sea at the mouth of Loch Claìdh lay as still as marble next to the shore. I could look down into its green depths twenty feet to the cobbled bed and see the starfish sprawled across them. On shore, with the sheep nosing among the stones, was the ruined and abandoned hamlet of Bàgh Ciarach, ‘Gloomy Bay’, where the murders of 1785 were committed. The buildings lay in shade, plastic flotsam clogged the beach and I had no desire to land. This is known as the most haunted place in Lewis and I was happy to stay offshore in Freyja, looking at the sour abandoned township from the comfort of her thwarts.

As Donald Macdonald, the historian of Lewis, has described, and as Dan MacLeod of Lemreway told me the story, the people from the village of Mealasta in Uig had gone to Gairloch on the mainland for wood to build some new houses. When in the Sound of Shiant on their return, a terrible storm out of the north-east overtook them. In a blizzard, they were forced to seek shelter here in Bàgh Ciarach, where two or three houses were occupied by poor people called Mackay: ‘The natives of these parts, seeing the weakened condition of the crew, frost-bitten and unable to defend themselves, and envious of their boatload of tree-trunks, killed each in turn by hitting him on the head with a large stone contained in the foot of a stocking.’

As Dan Macleod told me, ‘the bodies were buried in a bog and an unusual kind of weed has been growing there ever since.’

The women of Mealasta thought their men had drowned but one night the ghost of one of them appeared to his sweetheart and sang her the song called ‘Bàgh Ciarach’:

The girl of my love is the young brown-haired one.

If I were beside her, I would not suffer harm.

This year my family are seeking and searching for me,

while I lie in Gloomy Bay at the foot of a pool.

The men of Pairc threatened us with axes,

But our utter exhaustion left them unharmed.

Duncan, the mountain man, attended to me:

the world is deceitful and gold beguiles.

While climbing the hillside I lost my strength.

By the crags of the headland the blond-haired boy was murdered.

The young woman woke with the words of the song and its tune on her lips. The next July she was at the yearly cattle market in Stornoway. A huge crowd of people was there. Among the crowd, as Dan Macleod said, ‘the Uig girl saw a jersey she had knitted herself, for her dead lover, on the shoulders of a man from Pairc. She recognised the pattern of her stitches and she grabbed the wool, pulled at the man, but he broke away from her and disappeared into the crowd. No one knows if he was ever brought to justice.’ Another version, told by Donald Macdonald, says instead that the girl was looking through a pile of blankets for sale at the fair. As she picked through them, she saw, on one of them, in its corners, the small pieces of tartan she had sewn in there herself. It was Nicolson tartan and the men from Mealasta were Nicolsons.

It was late on a summer night, after eleven o’clock. I turned Freyja southwards, raised the sail and started back along the Lewis shore to Scalpay and the MacSweens. A light northeasterly blew in over my left shoulder. The motion through the still water at the mouth of Loch Seaforth was as easy as those first days’ sailing in Freyja in Flodabay. The water rattled against the boards of the hull like a ruler against the railings of a fence. For all the melancholy of the eighteenth-century history here, I felt happy, at home on the summer night sea. The dogs slept on the boards at my feet. The moon rose as the Shiants sank into the dark and at one in the morning, as Freyja and I slipped in between the arms of Kyles Scalpay, I watched its reflected light around me, scattered and broken on the bubbling of the tide.