16

I WAS ALONE ON THE ISLANDS again in the very last of the autumn. It was the beginning of October and winter was in the offing. I was waiting for the geese to return from Greenland. Every day, I would go up to the cliffs of Garbh Eilean with the binoculars, lie down on the grass there by the Viking grave, and look out to the north, hoping to see the moment when they would come back in, the flock wheeling out of the northern sky, fresh from Iceland and the Faeroes. It was cold and wet. The days had shrunk and I could feel the year closing down around me. The summer birds had gone and all the people had left. There were no yachts on the winter Minch. All the business of the year, the comings and goings of the experts and scientists, historians and archaeologists, shepherds and fishermen, was done with and at last a kind of silence had descended. The islands were empty now, in a state of suspension, and a powerful absence hung over them.

Back in the house, I sat over the fire and warmed my hands, while the dogs nuzzled their bodies next to me. A party of three shags flew low across the sea towards the beach and a family of eiders, all now grown, bobbed in the chop beside the black rocks. I looked out of the door at the cardboard-grey of the sky, felt the rain spitting at my face, went back in and switched on the radio. In a studio in Portland Place, a man I knew, an art historian, was speaking about EM Forster in Tuscany, the colour of apricots and the feeling of sun-warmed terracotta on the palms of his hands. Apricots would never have been eaten in the Shiants. Cherries would have been unknown. There was an orchard on Eilean Chaluim Chille in the mouth of Loch Erisort and apples might have come over from there. No plums, though, nor peaches or nectarines: only the unyielding substance of Shiant life.

I turned to the fire and scraped the chair a little nearer across the lino. In Gaelic, you can only say you are ‘in the islands’ not ‘on the islands’ and ‘in’ is the right word. The Shiants on days like this surround and envelop you. You are embedded in them, not perched on top, not the tourist but the occupant, as secret here as a puffin in its burrow or a man in his bed. I could pull the islands around me like a coat against the wind.

It was too late in the year for Freyja. I had taken her back to Scalpay a few weeks earlier. The weather on the evening before I left had been threatening, a cold southwesterly, driving the waves on to the beach. It had been a high spring tide and the sea had broken through the isthmus, as it does from time to time, so that the surf tailed out into the bay, where the gulls picked at it, looking for the little shrimps, I suppose, that had been washed out of the old weed on the shingle. I had my mobile phone with me – an innovation, as during 2000 a series of masts were erected in Lewis and Harris – and rang Rachel MacSween in Scalpay. ‘Is that Adam?’ she asked. ‘In a muddle as usual?’ It was. I asked her whether Donald, if he was around, could look out for me the next day. And perhaps take Freyja in tow if I was having difficulties on a lumpy sea? She said she would ask him. And she would see me that afternoon, ‘with your dirty washing as usual. And you dirtier than it.’

As it was, the day was easy, and Freyja took a straight run in from the islands to the mouth of the Sound of Scalpay. When I was still a good way off, I saw a boat coming out towards me. It was Donald in the Jura. I had waited for the tide and it was now early in the afternoon. He been been fishing for prawns since four o’clock that morning and instead of going home to wash, eat and sleep, had come out to see that I was all right. ‘That’s you, Adam,’ he said on the radio.

‘Yes, Donald,’ I said, ‘I don’t know how to thank you.’

‘Ach, no bother,’ he said, ‘no bother, no bother at all.’ With that, he swung the wheel and I saw the Jura ahead of me taking a wide sweep around on her own wake. We were soon alongside.

‘How’s it been?’ I shouted up at him. He was looking out through the window of his wheelhouse, a tired face, with his crewman Donald MacDermaid standing outside on the deck.

‘A desperate week,’ he said. ‘The prawns aren’t there. You’re all right though? Have you had a good time?’

‘A wonderful time,’ I said.

‘Well, that’s all that matters then. See you later.’ He leant on the throttle and the Jura surged towards the Sound and the North Harbour in Scalpay, leaving me in her wake, wondering if anywhere else in the world a man would come out for you like that.

The twentieth century on the Shiants became increasingly a history of men at play. It was the holiday century where southerners with southern money came to entertain themselves in a romantic and deserted island. To begin with, a faint echo of productive use hung on. Lord Leverhulme, the Lancashire soap magnate, who bought the Shiants as part of Lewis in 1917, visited them three times. According to Neil Mackay, one of Leverhulme’s employees who accompanied him, the Lord of the Isles first arrived at this remote speck of his island kingdom under a terrible misapprehension:

His Harris factor had told him that the islands were overrun by rabbits. ‘Right,’ said Leverhulme. ‘I’ll breed silver foxes there. Foxes eat rabbits and rabbits eat grass, so it will cost me nothing.’ As they were approaching the island, I told him that he had been misinformed. There were no rabbits on the Shiants but large numbers of rats. Leverhulme was furious and on that occasion didn’t even land but turned back for a dance in Tarbert.

All the same, despite these horrible inhabitants, there is a hint that Leverhulme might have loved the place too. After his death, very nearly the entire Leverhulme estate in the Western Isles was put up for sale, broken into lots. The auction was held on 22 October 1925 in Knight, Frank and Rutley’s Estate Room at 20 Hanover Square, London. The Shiants were Lot 13. It was the first time they had ever been sold separately from the other 355,000 acres of Lewis also up for sale that afternoon. ‘These interesting and rugged Islands,’ the catalogue began a little waftingly, ‘extending to an area of about 475 acres, upon which there are no buildings, but which are the haunt of numerous sea birds, are let as a farm to Mr Malcolm Macsween on a lease expiring Martinmas 1928, producing an annual rental of £60.’ If that didn’t sound very inviting, there was this specious worm dangled off the end: ‘The rights of netting salmon in the sea ex adverso of this Lot are included in the sale.’

Both then and now, salmon are seen leaping in the bays of the Shiants about as often as a Blue Man invites himself aboard the Uig-to-Tarbert ferry. ‘These islands are the breeding ground of hundreds of seals,’ Malcolm MacSween later told Compton Mackenzie, ‘and you know how salmon and seals agree to share a coast. “The former are always devoured by the latter.”’

Perhaps the Shiants were made to sound deliberately boring because Lord Leverhulme’s son had told the auctioneer, Sir Howard Frank, ‘to see that he obtained this Lot. He desired for sentimental reasons to reserve this small portion as a memento of his father’s interest and also because he was now Viscount Leverhulme of the Western Isles.’

Sir Howard, thank God, was incompetent. He recognised a man among the throng in the auction room and for some reason assumed he was bidding on behalf of the Viscount. He wasn’t. He was a professional valuer, a fan of Compton Mackenzie, the novelist, and had instructions from him to bid up to five hundred pounds for the Shiants and no more, half of a book advance which had unexpectedly come Mackenzie’s way. Five hundred pounds was little for an island producing sixty pounds a year rent, never mind the other benefits. ‘The bids went in quick succession and I put in my top figure, and Sir Howard knocked it down to me.’ There was a row but the sale had been made and Compton Mackenzie was now the owner.

Perhaps it is true of any island, but over the decades, from generation to generation, anyone who has known the Shiants has come to love them.

Malcolm MacSween to Compton Mackenzie

October 1925

Sir,

I write this note to introduce myself as I understand you are now my proprietor … I became tenant 4 years ago and I myself had a small offer on them, but was not extra keen on account of recent reasons I need not touch on at present. I have about 200 ewes on the three islands. But they are capable of grazing another 200; if I could afford to get them … I do not keep a shepherd. It is too lonely a spot for a shepherd. I couldn’t get anyone to go. There was a shepherd on some time and the stone wall of the house is still as good as the day when he left … Only that one of the gables fell off a bit … I will await your further consignment of queries which I will be always pleased to answer. I am quite sure of this that you will really enjoy a trip to these ancient islands and any time you come I will make it my business that you will get out to them as comfortably as possible.

Compton Mackenzie eventually married two of MacSween’s daughters, Chrissie, the elder, and, after her death, Lily, whom he had first met in Tarbert in 1925 when she was eight years old. He was a fervent Scottish nationalist and, as his biographer Andro Linklater has said, the Shiants were for him ‘a talisman of Scotland’. As Compton Mackenzie wrote in an article soon after buying them,

To most people, the Shiant Islands mean nothing. To some they mean the most acute bout of sea-sickness between Kyle and Stornoway as the MacBrayne steamer wallows in the fierce overfalls that guard them. To a very few they mean a wild corner of the world, the memory of which remains for ever in the minds of those who have visited their spellbound cliffs and caves …

In the incomparable beauty of their sea, their rock and their grass – ‘the bottle-green water at the base of this cliff, the greenish-black glaze of these columns, that lustrous green of the braes and summits …’ – they were a link to his Mackenzie ancestors. He reroofed the house which the Campbells had left in 1901, putting corrugated tin over it, panelled the inside and used it for a day or two at a time to write. The Shiants is the setting for his two-volume novel, The North Wind of Love, published during the war, in which they are called the Shiel Islands. The hero, a Mackenzie-like playwright, John Ogilvie, builds a house (with a Tuscan loggia!) on Eilean Mhuire, called Castle Island in the book, from which he dreams of and plots for an independent Scotland.

At one point, Ogilvie/Mackenzie, suffering from acute Shiant-love, takes his daughter Corinna to a favourite place at the far end of the island from the house:

There was one cave in which a great emerald of sea-water blazed in what seemed the heart of it, and from the roof enamelled with rose and mauve a slim silver freshet spurted forth to meet the sea-water in a perfect curve. And then as the boat penetrated deeper the air in the cave lightened and the sides danced with reflected ripples until presently it was seen that the cave was an arch leading to a beach so nearly hidden by great basaltic columns on either side that they had passed it in the boat unperceived.

‘I don’t think there can be anything so lovely as this anywhere, do you?’ Corinna asked her father.

In his ginger suede shoes, his green check suit, his pipe, his posed stance in front of the fireplace, with the writing room in his house in Barra wallpapered in gold and his dazzling ability to write a novel while listening to a record he was reviewing for the magazine Gramophone, Mackenzie bewitched the Hebrideans. The Shiants have never known a man like him. But it was this theatrical egotism, allied to the obsessive habit of moving from one island to another, from Capri to Herm and Jethou in the Channel Islands, on to the Shiants (via an unsuccessful attempt to buy Flora Macdonald’s house at Flodigarry on Skye) and then Barra, which lay behind an attack made on him in 1926 by DH Lawrence. The Nottinghamshire apostle of candour and intimacy would never have condoned the play-acting, self-aggrandisement and self-regarding island-love to which Compton Mackenzie was prone. ‘The Man Who Loved Islands’ was a scarcely veiled attack on Mackenzie for which Mackenzie never forgave Lawrence. The story is the only moment a writer of world standing comes anywhere near the Shiants: ‘There was a man who loved islands. He was born on one but it didn’t suit him, as there were too many other people on it beside himself. He wanted an island all of his own: not necessarily to be alone on it, but to make it a world of his own.’

The love of islands, the story maintains, is a neurotic condition. They are not so much islands as I-lands, where the inflated self smothers and obliterates all other forms of life. The story ends with the Mackenzie-like figure contemplating what had once been his beautiful private landscape now dead and sterile under drifts of egotistical snow. The place had died at the hands of an imposed personality.

It is not a great story, too much the working out of a theoretical type, but it is a symbolic moment in the history of the Shiants and it marks a change in the history of attitudes towards islands. In the early eighteenth century, to Robinson Crusoe, for example, an island was in some ways a prison, a symbol of his suffering, divorced from the company of men, full of hostilities which his own energy and enterprise must struggle to overcome. An island was a reduced form of what the world could offer.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, that view had begun to change, largely at the hands of one man. The grandfather of the modern love of islands, of all those visitors to the Hebrides, of Robert Louis Stevenson and Gauguin, is Jean-Jacques Rousseau. It was Rousseau who invented the idea that islands were not somehow less than what the world could give you, but the most perfect of places in which the solitary self could flower.

In the autumn of 1765, Rousseau went to live on the tiny Ile St Pierre, set in the Lac de Bienne in northern Switzerland. He had recently been stoned by religious conservatives in the Swiss village of Môtiers, and on the tiny island, where there was a farmhouse, his paranoias and fears were calmed. He felt secure within those visible shores. He botanised with patience and care and had a plan to write a book about this most precious and protected place. People might mock, he thought, but love of place could only attend to minute particulars. ‘They say a German once composed a book about a lemon-skin,’ he later wrote. ‘I could have written one about every grass in the meadows, every moss in the woods, every lichen covering the rocks.’ The Ile St Pierre was the Eden away from society that he sought:

I was able to spend scarcely two months on that island, but I would have spent two years, two centuries and the whole of eternity without becoming bored with it for a moment. Those two months were the happiest of my life, so happy that they would be enough for me, even if they had lasted the whole of my life.

That was probably Compton Mackenzie’s view of the Shiants too. But Lawrence’s point is the modern and post-Freudian one: the healthy state is social; isolation is aberrant; and islands represent a withdrawal from the mainstream where in some ways it is our duty to remain. This is a return to the early-eighteenth-century view that uninhabited islands, and other stretches of empty country, are places which would be better off occupied, used and made social. In Scotland, because of the continuing resonance of the Clearances, this remains a powerfully held position: the cleared is the wronged; empty land is an insult to society; privacy is an indulgence of the powerful; there is no distinction between ‘land’ – the acres – and ‘Land’ – the nation; and in that coalescence the land clearly should belong to all. It is inconceivable nowadays that a Scottish Nationalist would proclaim his private ownership of the Shiants in the way Mackenzie did. He would have transferred it to the community many years ago.

Eventually, Compton Mackenzie had to get rid of the Shiants for more mundane reasons. His finances had been chaotic for years and finally, in 1936, to assuage the bank manager and the Inland Revenue, he had to sell the islands. Malcolm MacSween was in (slightly befuddled) mourning when Colonel MacDonald, DSO, of Tote in Skye offered himself as a purchaser.

Malcolm MacSween to Colonel Macdonald, May 1937

Mr. Mackenzie never charged me for rent. But of course Mr. Mackenzie’s equal is not to be found in Scotland. No more than is better than his island’s grazing is to be found. He is and was the best friend I ever had.

Mackenzie squeezed fifteen hundred pounds out of Macdonald, whose elaborate scheme involved the intermittent transfer of horses, sheep and cattle between the Shiants and a farm on Skye. It was never realistic and within a matter of months he readvertised them. My grandmother, Vita Sackville-West, wrote to her husband Harold Nicolson:

I’ve got another activity in view: three tiny Hebridean islands for sale, advertised in the Daily Telegraph today, 600 acres in all. ‘Very early lambs. Cliffs of columnar basalt. Wonderful caves. Probably the largest bird colony in the British Isles. Two-roomed cottage.’ Do you wonder? I have written to the agents for full particulars and photographs. They cost only £1,750.

She sent those details to my father, Nigel Nicolson, who was then at Balliol aged twenty, having just inherited some money from his grandmother. He was as drawn to them as Vita had been and that summer he visited them for the first time. His mother would not let him stay the night, frightened that he would be trapped there by storms, and so he had a single day in which to make his decision. He fell in love with them on the spot. As he wrote in his autobiography, Long Life:

I loved their remoteness, isolation, grandeur. Was it romanticism or melancholy? Both, added to an atavistic desire to own land in the Hebrides (the Nicolsons were originally robber-barons in the Minch), to have an escape-hole, to enjoy nature in the wild … On me the difficulties of access to the Shiants acted as a magnet, on others as a deterrent. There would be some danger in total isolation – cliffs, tides, illness – when there was no form of communication to summon help. Of this I would boast, magnifying the risks. Looking back, I recognise an element of arrogance in my island mania. I would be different from other undergraduates. I would be the man who owned uninhabited islands and marooned himself there alone.

He would, in other words, be The Man Who Loved Islands, as I have been and no doubt as Tom will be. It is not, I think, something to be ashamed of. The growing sense of your own capacity to survive and thrive in a difficult environment; to handle a boat in strange and disturbing seas; to look after yourself with no crutch to lean on: all of these experiences are wonderful for the kind of immature young men my family seems to produce. But one grows out of it and moves on to other things. Perhaps, I now think, the love of islands is a symptom of immaturity, a turning away from the complexities of the real world to a much simpler place, where choices are obvious and rewards straightforward. And perhaps that can be taken on another step: is the whole Romantic episode, from Rousseau to Lawrence, a vastly enlarged and egotistical adolescence? And one last question: is this why women tend not to like the Shiants? Because they are so much more adult than men?

At a loss of a hundred pounds to Colonel Macdonald, the Shiants were finally transferred to my father and he spent the month of August 1937 there on his own. He nearly drowned, when a collapsible canoe did indeed collapse halfway between Eilean Mhuire and Garbh Eilean but that wasn’t the only catastrophe. His supplies had been sent up by train from Fortnum & Mason – it was a different world – in smart, waxed cardboard boxes. They were delivered to the quayside in Tarbert. From there they were loaded onto the fishing boat and on arrival at the Shiants offloaded on to the beach. My father waved goodbye to the fishermen, who said they would return in a month’s time, carried the boxes to the house and began to open them. As he folded back the cardboard flaps, he found a neatly typed note from the Manager:

Dear Mr Nicolson,

Please find enclosed the supplies as requested. Unfortunately, due to Railway Regulations, we are not permitted to dispatch flammables by rail and therefore have not been able to include the safety matches you requested. Trusting this will not be of any serious inconvenience, we remain,

Yours etc..…

Faced with the prospect of a month without a fire, my father dismantled his binoculars and with one of the lenses managed to focus a few rays of the watery Hebridean sun on to some dry bracken. Somehow a flame sprang up and he carried it between cupped hands to the fireplace in the house.

For the four weeks he would have to nurture the fire like a dying lamb, returning to it at least once every two hours to see that its heart still beat. All went well, until one day returning from a walk on the heights of Garbh Eilean, he was horrified to see from above that a yacht had anchored in the bay and a party from it was picnicking on the beach between him and the house. If he was to get back to the fire, whose thin grey thread of smoke he could just see trickling upwards from the chimney into the sky, he would have to pass the picnickers. That in itself would not have been so bad if he had been wearing any clothes. He wasn’t. It was a 1930s habit to walk about in wild places undressed.

Unobserved from the beach, he waited crouched behind a rock for the picnickers to leave. They were having a marvellous time. Sprinklings of laughter came drifting up to him. The young men and women in their yachting skirts and blue jerseys lay back on the warmth of the shingle. The hours went by. The trickle of smoke from the chimney had thinned to invisibility. There was nothing for it. Dressed only in what he describes as ‘a apron of gossamer fern’ my father strolled with as much dignity as he could, past the picnickers and on to the house where with flooding relief he could dress himself and restore his faltering fire to life.

The following year, he invited a friend from Oxford, Rohan Butler, to the Shiants and although Vita never came to the islands, his father and his brother Ben hired a ketch to visit them. Harold wrote in his diary that night:

We cast anchor. We get into the dinghy, and hum along the placid waters, and all the puffins rise in fury. As we approach the beach, two figures run down to it. Nigel and Rohan. We walk round to his little shieling. Niggs is glad to have a day like this to show me his romance. It is like a Monet, all pink and green and shining. I have seldom in life felt so happy. After lunch, we go round the islands in the dinghy. The cliffs are terrible and romantic. We sing for the seals and they pop up anxious little heads. It is lovelier than can be imagined.

The Shiants have never quite been what others have imagined. ‘Islands in Scotland’, mentioned like that in London, the words tossed away at a party, as the cigarette ash is brushed from the sleeve, always sound too comfortable. You can see the illusion in your listeners’ eyes, the warm air, the distant horizons, the polychrome sunsets; they are imagining a glass of old malt in a deep armchair, bannocks in the tin beside the bed, a blue tweedy atmosphere, perhaps a hint of Scottish baronial. Anyone who has persevered this far will know by now that the Shiants are not quite like that. And the rats don’t help.

It seems at times my father may have suffered from this very delusion. It came to an abrupt end in the summer of 1946. He had decided to invite two of London’s most glamorous girls to the Shiants. Both Lady Elizabeth Lambart and Margaret Elphinstone, the daughter of an Invernesshire grandee, were beautiful. Both were grand and both would be bridesmaids at the wedding of Princess Elizabeth the following year. Margaret Elphinstone was the niece of the Queen. What can have been in Nigel’s mind?

He arrived a week before they did to tidy up. The weather was filthy. ‘I found the house in quite a good state,’ he wrote bravely in his diary, as the rain slashed around him. ‘There are a lot of holes, some made by the rats and some by the weather. You can see right through the ceiling and roof in the other room and the door is off its hinges. The stove has rusted to bits and has been thrown outside.’

Day after day he washed, scrubbed and painted. The sound of scurrying rats accompanied his ‘scrubbage programme’, skittering across the rafters, sliding down between Compton Mackenzie’s panelling and the wall, stealing his cheese at night. The clean-up was not a success. ‘Scrubbing is a beastly job,’ he wrote in the diary. ‘One makes circular sweeps with the brush, expecting to clear a path of cleanliness with the soap, but all it does is leave a soapy smear, and soon one’s other cloth becomes so dirty that it simply re-dirties the floor. I clearly haven’t got the technique right.’ The rats were so disturbing that he decided to erect a tent in which the girls would be put to sleep at night. He turned for consolation to Harold J Laski on Liberty in the Modern State, reading about the coming disintegration of the capitalist system by the light of a guttering flame.

Malcolm MacSween had forgotten to put a tin opener in with the supplies. He tried opening the cans of soup with an axe, but it spoiled both axe and soup. Within three days, the fresh meat, bacon and eggs started to go bad. Nigel threw them away. That left him with ‘potatoes, oat-meal and bread as my main diet. There is enough of all of this to last a fortnight.’ No doubt the girls would love it. He started to poison the rats and within a day or two thought that the poison was working so well that the girls could sleep in the house itself. If they noticed the holes in the skirting board, he would tell them that once, many, many years before, there had been a plague of rats. But wasn’t everything lovely now?

Doubts continued to haunt him. What if the grown-up rats had died, leaving their little babies behind who would spend all night squealing for their mothers? What if the grown-up rats had died but in the house? The girls would never have been exposed to such smells. Everything else, apart from the weather, seemed to be all right. He had washed all the pots and pans again, boiled the cloths, painted the windows and laid a small gravel terrace outside. At least at first sight, Number One, The Shiants would look welcoming. But behind this sweet facade lay the terrible anxiety. He should never have asked them.

The night before the girls were due, he thought he should sleep in the room he had prepared for them, if only to accustom the rats to the idea that this was not their playground but a place fit for human habitation. He woke up in the early hours, as the summer light was leaking in through the window. A rat was sitting on his bed looking at him. ‘I shall simply have to warn the girls.’

They arrived. He toured them round the sights. He gave them some of his oatmeal, bread and potatoes. They went to bed at midnight. At half-past three in the morning, Nigel, on the camp-bed in the other room, heard them screeching with horror. A rat had got inside the chest of drawers he had installed for their change of clothes in the morning. It was running up and down the nearly empty drawers like a tap dancer in paradise. Nigel – social mores were different then – asked through the door whether he could do anything to help. ‘No, no!’ they shrieked. ‘If you let it out, it’ll run all over us.’ They spent the rest of the night awake, shaking, hidden under their blankets.

The calamity wasn’t yet over. The wind and tide had got up in the night. Nigel, in his anxiety, had forgotten to tie the dinghy to the mooring ring in the rock on the side of the beach. (It happens to us all: I have lost two boats like that; Hughie MacSween lost one, which he watched floating away from the islands, only for it to be picked up by a fishing boat and delivered back to him at the end of the week.) No such luck for my poor father. The dinghy had been swept away and then smashed on the rocks of Eilean an Tighe.

When the fishing boat arrived to pick them up the next morning, there was no way of reaching the boat from the shore. Nigel entered the freezing waters of the Minch, swam out to the boat and returned to the beach with a rope. Elizabeth and Margaret stood waiting in their floral prints. Nigel tied them on, one by one, and they swam out towards the herring drifter, speechless with cold, while their skirts spread like peonies around them.

Nobody knows when the rats arrived. In 1925, Malcolm MacSween told Compton Mackenzie that they ‘came ashore from a Norwegian ship’ twenty years before, but there was no wreck on the Shiants then. In January 1876, the Newcastle barque Neda had been wrecked on Eilean an Tighe and on 13 February 1847, the Norwegian schooner Zarna, of Christiansund, was wrecked here, perhaps on Damhag, en route to Norway from Liverpool with a cargo of salt. The crew somehow managed to get ashore, salvaging two sails, ‘with which the Seamen contrived to make a tent for Shelter.’ The rats may have come on either of those ships, or neither. They may have been here ever since ships began to ply these seas in any number in the eighteenth century. ‘Since the great rat took possession of this part of the world,’ Dr Johnson heard on Skye in 1773, ‘scarce a ship can touch at any port, but some of his race are left behind. They have within these few years began to infest the isle of Col.’

Twentieth-century life on the Shiants has certainly been intimate with the rats. Bullet Cunningham, lobster fishing here before the war, was staying in one of the old bothies.

You saw the old thatched houses we were staying in? Some of the walls are up yet. The rats there, I was dead scared of them. My father and the others, a very regimental man he was, he went out one day to lift the creels and left me to do a bit of cooking. And I was going to cook potatoes and some herring for dinner for them coming home. I boiled the herring, the herring was ready and all things like that … and I was just going to get the potatoes ready and I saw a rat coming through the holes in the walls – a rat like that - and as soon as I saw that I got dead scared and I just ran out of the house and left the pot on the fire. My father came home and of course none of the dinner was cooked and my father came home and when he saw and I told him what had happened, do you know what he said? ‘There’s not a rat in the world quite as rat-like as yourself.’

The rats have a reputation. Tell anyone in Lewis or Harris that you are going out to the Shiants for a week and a distant, quizzical note enters the voice. ‘Ah yes,’ they say carefully, as if you had announced that your next holiday was to be in Broadmoor, ‘and what are you thinking of doing about the little creatures?’ Malcolm MacSween put some cats on here, but it is said in Harris that the rats ate them too.

The rats are certainly horrible things, mostly, I think, for their lack of fear. When the house has been full of shepherds, I have slept on the floor and woken up with one a yard from my face. It looked at me quite undauntedly, even when I jumped and shooed it. We have poisoned them consistently, year in, year out, but only around the house and that has had no effect on the wider population. They are on all three of the islands and are thought to number about three thousand. They can breed when they are three months old and produce four or five litters a year, each with between six and twenty-two babies. The reproductive potential is spectacular. With an unlimited food supply, the three thousand Shiant rats at the beginning of the year could, mathematically, have multiplied to something like 1.8 million by the early autumn. They don’t because life here is a desperate struggle.

They are not the rats you find at home in the barn or the sewer. Those are brown rats, Rattus norvegicus, relatively large, relatively aggressive and relatively horrible. These are Rattus rattus, the ship, black or plague rat, originally from South-East Asia and now one of the rarest mammals in the United Kingdom. Because the brown rat is bigger and stronger, there are very few black rats left. Only on the Shiants and on Lundy do they exist in any number.

This is a glamorous status. The Shiant rat is now infinitely rarer than, say, the puffin, which may well be Britain’s commonest sea bird. As a result, a string of rat investigations have been made in the last few years. Margarine-coated sticks have been stuck in the soil at intervals across the islands to see where the rats lived. (A nibbled stick meant a rat.) The unsurprising result was that every stick was nibbled. Rats have been caught to see what was in their stomachs. (A mixture of things from shoreline crustacea to moss and grass.) Most eccentrically of all, an English biologist received a grant to find out where the rats went on their nocturnal wanderings.

The interesting question, though, is how the rats and the birds manage to coexist. Why haven’t the rats wiped out the birds? The answer is a vindication of the puffins’ strategy. The birds are here only from early April to mid-August: four and a half months. While they are, the rats make hay. (Evidence from elsewhere has shown that a rat can kill an adult puffin.) But it seems as if the rats can’t make sufficient impact on the bird population before they leave for the Atlantic. Come late August, the rats are suddenly proteinless and in all likelihood the population crashes. It is just then, incidentally, that the pressure of the rats on the house, which they seem to neglect for the summer, becomes most intense. Winter starves hundreds if not thousands of the black rats and so keeps their predation on the birds to a level at which a kind of equilibrium is reached. It has been different where the bigger brown rat has preyed on sea birds. On Ailsa Craig, and other brown rat-infested rocks, the rate of predation, which must be slightly higher, has sent the bird numbers irrevocably downwards. So the Shiants have a rat-puffin balance, if a fine one. We shall never rid the islands of the rats and the rats will never rid the islands of the puffins. It wouldn’t take much to change this, though, and there is one thing everybody dreads: the arrival of a pregnant mink. It might kill the rats but it would also decimate the birds.

The one difference which the twentieth century made to the Shiants was the idea that they should be ‘conserved’. The shoulders of what Hughie MacSween once described to me as ‘our beloved Islands’ now sag beneath a heavy load of modern conservation labels. They have been designated under a succession of governments as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, a Special Protection Area, a Nature Conservation Review Site (Grade 2) and a Geological Conservation Review Site. Most recently, under the European Community’s Birds Directive, they have become part of the Natura 2000 Network. It all reminds me of some ancient military personage: Admiral of the Fleet Lord Shiant of the Minches SSSI AONB SPA NCRSii GCRS ECN2000. He staggers under the honours he wears. Every February, I am obliged by law to tell the Land Management Administrator of Scottish Natural Heritage, the government’s conservation agency, at their North-West Regional Headquarters Annex in Inverness, exactly what I have been doing with the place.

1. Information and expenditure [actual and planned]

2. Details of maintenance [completed and outstanding]

3. Information on any positive works undertaken to safeguard the interest of the site

and finally, the one that is more pleasure to answer than any other:

4. Details of access arrangements including for pedestrian access only.

There was one occasion when SNH wrote to me asking what kind of vehicular access there was to the site. As it is, the answer to all the questions is always the same: ‘No change.’

At one moment in the early 1970s the conservation movement reached out its long acquisitive hand towards the islands. I have the letters on file and I read them now with an amazement at the arrogance they display. They begin with a letter from George Waterston, the Scottish Director of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, the RSPB, one of the most powerful and rich of all British conservation organisations. It is addressed not to my father but Colonel Sir Tufton Beamish, President of the RSPB.

23rd March 1970

Dear Tufton,

The Shiant Islands

This very interesting group of small islands lie some 12 miles north of Skye and about 5 or 6 miles east of Lewis.

The islands comprise a most important seabird breeding station; and when I landed there many years ago with James Fisher (from a National Trust for Scotland Cruise) we found vast numbers of Razorbills and Puffins nesting.

There is an attractive small bothy near the landing place at Mol Mor between Garbh Eilean and Eilean an Tigh. It seems to me that the group of islands would make a most attractive Bird reserve, and I wondered whether you could approach the proprietor, Mr Nigel Nicholson, MP?

My hackles rise even thirty years later. Why did George Waterston think that he could do things here any better than we could? Beamish, an old friend of my father’s, sent the letter on with a fair wind.

27th March 1970

You could be confident that we would take sensible and active advantage of an opportunity to make a bird reserve on the Shiant Islands.

My father replied, asking what the RSPB would like to do with the Shiants. He had no answer for two and a half years. He then received a long letter from George Waterston’s successor as the head of the RSPB in Scotland, Frank Hamilton, explaining what they had in mind. Nigel would have to agree not to alter or develop the Shiants without consulting the RSPB. He would also ‘agree subject to consultation’ to various improvements such as ‘tree planting, provision of water flashes, erection of hides for public viewing etc. etc. These are not necessarily suggested for the Shiants, they are merely an illustration of the sort of things sometimes included in an agreement.’ Mr Hamilton also suggested that the RSPB should be responsible for visitor control. That is what had happened on the island of Handa off the Scottish mainland, where a management agreement had been put in place and where the news of the RSPB’s involvement had resulted in an increase in the number of visitors:

Numbers have gone up to such an extent that a summer warden has become necessary to control and to mitigate damage both to the wildlife and the habitat. And the way we have done this in that particular case is to lay out a definite path to which we ask people to keep, thus ensuring that ‘delicate’ areas are protected. It is not uncommon for us to develop such a path as a nature trail giving visitors information about particular points of interest.

Finally, with some delicacy, Frank Hamilton brought up the slightly longer-term question:

Legal ownership would in no way be affected, although you might, if you felt it worthwhile entering into such a management arrangement, consider the possibility of writing in a provision for the Society to be given the first option to purchase in the event of your deciding to sell.

Something in Mr Hamilton’s description of the RSPB’s vision for the Shiants produced a response from my father for which I shall be forever grateful. He told Mr Hamilton that he was a little puzzled by the RSPB’s motives. What was the point of making somewhere a nature reserve which, thanks to ‘its very isolation, inaccessibility and lack of human habitation’, was already as protected from interference as any place could be? In fact, if the RSPB got involved with the Shiants, that might well be the most intrusive development the islands would ever have known: ‘A sudden influx of visitors might lead to disturbance, the appointment of a Warden, rules and regulations, “nature trails” – in fact all the business of regulated access which presupposes and even encourages such access.’ Nigel would have to consult the RSPB on all manner of details, such as the areas which could be grazed by my tenant’s sheep, the erection of hides for public viewing, visitor control, permission for my friends to land and camp there, and so on and so on. And for what purpose?

Mr Hamilton replied with a new reason for the RSPB to get involved: the Shiants were threatened by oil rigs in the Minch. Only with the RSPB at the Shiants’ side could they be protected from this new threat:

If an agreement, or better still a lease, were entered into by the two parties this would ensure that, should a developer come along at some later date, we could show them that there was a legal document to indicate that the R.S.P.B. thought highly of this place, enough to make it a reserve.

My father saw this for what it was – an empire-building bogey – and rejected the argument. If there was oil discovered in the Minch, the Shiants would be spoiled anyway. The RSPB could do nothing about it. With an agreement, however, he would be landed with an obligation to refer to the RSPB in everything he did. The answer was ‘no’. Mr Hamilton replied, hoping that my father would ‘appreciate that our desire is to see the Shiants unspoiled for many generations to come.’ There hasn’t been a squeak out of them since. I told John Murdo Matheson this story once. He said, ‘Promise me one thing, Adam. You will never, ever let one of those organisations get their hands on this place. It would be the end of it, the real death of it. It needs to belong to a person who loves it.’

‘It does,’ I said, ‘and it will.’

Tangled in with these two modern Shiant strands, as a place for holidays and a place for nature conservation, is a third: the working environment for the shepherds. The categories are not quite watertight: the shepherding trips to the islands are a kind of hard-working holiday. But I have always felt that the shepherds’ relationship to the islands, because of their repeated, deep familiarity with the contours of the place, decade after decade, and because of the sweat expended and the dangers undergone here, is much deeper and less trivial than all the passing summer visits of the proprietors, whether Leverhulme, Compton Mackenzie, my father or me. I believed the man who told Hughie MacSween in the Tarbert pub that he was the true owner of the place. However much we attend to the Shiants, however much Mackenzie’s novel or this book are a tribute to them, there is no matching the intimacy that Malcolm MacSween, DB Macleod or Hughie achieved with them.

One can only sit back and listen to the stories: the day when Hughie lost his dinghy from the beach and thought he should try and float out to it on the lilo he had been using as a mattress in the house; or the day when trying to rescue some sheep stuck far down the cliff on Eilean Mhuire, dangling off a rope held by two of the boys up on the top, he slipped on the rain-slicked grass and hung there for a while, dependent on the strength of the men who were holding him. ‘That was the only time I really frightened myself there,’ he says, grinning and pulling on the lobe of his ear.

‘Now I start to hear about it,’ Joyce says as Hughie confesses to me the excitements of his life thirty years ago.

Hughie won’t be stopped now. His stories rumble on, ever quieter. What about the day when his uncle Calum, it was during the war, decided he had to take the cattle off? They were on Eilean an Tighe. The first beast they took out in the dinghy but they were worried one of them would put its hoof through the planks. So the rest of them were swum out on a rope and then attached to the steam derrick on the deck of the Cunninghams’ puffer. The men waited below in the dinghy as the poor beast was lifted by its horns high into the air, bellowing at the indignity and with fear. Just as the animal was high above the gunwale, the men in the dinghy guiding it in by the tail, the bullock emptied the entire contents of its four stomachs over the men below. That was the last time any cattle were seen on the Shiants.

At one time when they were there, a cow had somehow got itself into the house and had shut the door behind it. Who knows how long it had been there. It was lying down and we managed to get it on its feet and took it outside. It had not eaten or drunk for days, weeks maybe, who knows? So we brought it out and gave it water and it drank so much of the water, it was the water that killed it.

A deep drag on the cigarette: ‘Yes, yes. Aye, it was the water that killed it.’

Throughout his youth, Hughie had gone out to the Shiants with Donald Macleod, the butcher on Scalpay, known as ‘D B’ for ‘Donald Butcher’. He was a marvellously friendly, charming, avuncular man, his grey hair standing in stiff toothbrush bristles on his scalp, always in a big tweed jacket with leather patches on the elbow, and a habit of calling me ‘my dear’, holding me without affectation or ceremony by the elbow or shoulder. He was still the tenant of the islands when my father first gave them to me and would sometimes come out for the day on the fishing boat when I was there, to see the islands, just to have another look. What I never knew was that he was a poet and songwriter, famous in Scalpay and beyond for his songs, some of them a little risqué. There is a well-known one about a magnificent cockerel for whom the hens become increasingly desperate – ‘we couldn’t hear ourselves for the laughter,’ one Scalpay woman said to me when telling me about D B’s songs. Others were more romantic, often about his love for Mary, his wife. His most famous song was about the Scalpay Isle, a Scalpay woman fishing boat belonging to Norman Morrison. You can still hear it on the Gaelic radio from time to time. Iain MacSween, Hughie’s son, sometimes requested it to be played on a Sunday night when his father was out with the sheep on the Shiants, listening to the radio in the house there, and it is still sung at the Mod, the annual national Gaelic singing competition, where a prize called the Shiant Shield, endowed by Compton Mackenzie, is presented every year for the best example of traditional singing.

Something persists here in the world of the Shiants, a wholeness in the culture, despite the batterings it has received, which has disappeared from the rest of Britain. The idea of a butcher in southern England writing a song that brings together the wild romantic sea and landscape, his own love and fearfulness, his sense of the future and the persistence of his song after death – stock themes as these might be – is quite inconceivable. This is the enriched world to which the Shiants belong, to which D B belonged, to which Hughie and Donald MacSween belong and from which I am quite removed.

Another man with Scalpay connections, the great modern lyric poet Norman MacCaig who died in 1996 and whose mother was from Scalpay, asked, in the voice of ‘A Man in Assynt’, as the poem is called, the devastating question: ‘Who possesses this landscape? / The man who bought it or / I who am possessed by it?’

It is a reframing of all Donald MacCallum’s radical and passionate questions in the 1890s. Can one really buy a place like this with all its attendant associations? Do the conventional rights of property apply here as they might to a car or a flat in London or Glasgow? Can I say as the ‘owner’ of the Shiants that I ‘own’ them any more than any of those people who are heir to the sort of inheritance which so effortlessly shaped Donald Macleod’s poem? His own words answered those questions by not even addressing them, by his assuming an unadulterated intimacy with this world. How can an outsider ever compete with that?

Of course they can’t. In the late 1990s, with the coming of a Scottish parliament, these questions received a new burst of life. At its quietest, the land reform movement was insistent on at least a right of universal access to wild land. At its most radical, a view that did not in the end find much favour with the Scottish Executive, the idea of a private individual owning land was itself called into doubt. On a Scottish internet discussion group, alba@yahoogroups.com, the owner and convener of the group, Robert Stewart, a member of the SNP National Council, suggested early in 2001, just as I was finishing this book, that ‘all Scottish mountains, and certain other uncultivated moorland [should] be brought into perpetual national common ownership.’ I asked why and what benefits might accrue either to the place or to the local community from public ownership?

Stewart replied, in brief, that the land had traditionally belonged to the people and that it had been stolen from them by the Crown and its vassals: ‘I, personally, believe that land “ownership” is arrogant and pretentious. I cannot see how humans can claim to “own” and buy and sell land any more than we can claim to own and buy and sell the air that we breathe or the rain that falls from the sky.’

The same was true of all claims to ownership of fish or game, but all Scots, he felt, should have a right to rent ‘a portion of arable land sufficient for their needs.’

In Adam’s case, my objection would be to the concept of any person ‘owning’ three islands in the Minch. In my view, those islands should be taken into national common ownership to be managed and tenanted, but not sold, by the local community.

He asks what benefits would accrue either to the place or to the local community from public ownership. My answer would be that the main benefit is that control of the land remains with the local community, thus seeking to reverse the past experience of communities throughout Scotland, many of which have suffered at the hands of unscrupulous landowners, both foreign and home-grown.

I am in a strange position here. If I didn’t own the Shiants, I might easily say the sort of things that Robert Stewart says. Without some kind of institutional framework, there is no guarantee that a private owner, however beneficial, might not turn nasty and exclusive. Or at least that his heirs or successors might. But I am not in that position. I do own the Shiants. I love them and I have a duty to my son. I want Tom to be able to love them, and to love them without feeling an overpowering sense of illegitimacy in doing so. As the history in this book has shown, the idea that some moment existed in the past when the islands were held in communal bliss, which was then disrupted by greedy and rapacious landlords, does not match the facts. There were originally five family farms here, which at some time in the middle ages were agglomerated and held in common under a quasi-feudal system, owing rent in kind to the clan chief. That lasted until the deep disruptions of the eighteenth century, brought about by the coming of the market. There is nothing in this that can suggest the people of Lochs have any more right to the Shiants than I do.

Importantly, though, their right to them is no less than mine. It has been my purpose in this book to show how much the Shiants are part of the lives of everyone who lives on the opposite shore. They are not some naked place on which castaway fantasies can be played out, as if no one had ever lived there, but a richly human landscape. It is important to me that my ownership of the Shiants should reflect that and give the local community all the benefits which that community would receive if it owned them itself.

I would go further: private ownership of a place like this, if community-minded, can actually be more open and more flexible (responsive, for example, both to Scalpay and to Lochs, different communities with in some ways equal claims) than exclusive community ownership might be. Private ownership does not need to be hung about with the sort of regulations and notices by which public ownership is usually accompanied. No one who comes to the Shiants need ever know that they are welcome there. They can simply find it wild and beautiful. And anyone who wants to stay in the house, ratty or not, can get in touch with me on adam@shiantisles.net or, after 5 March 2005, with Tom on tom@shiantisles.net and they can have the key.

In the course of the debate in the discussion group, I quoted the words of Donald MacCallum and said that in many ways I agreed with them. It is historically true that all property is theft, reinforced with violence. Robert Stewart ended with this:

In admitting that “What the Rev. MacCallum said is true’, Adam Nicolson himself declares that no one has the sole right to ‘own’ the Shiant Isles and no one has the right to buy or sell them. He faces a dilemma. Should he maintain his claim of ownership of the Shiant Isles, which he admits is ‘dependent on a succession of acts of violence, quite literally of murder, rape and expulsion’, or should he make history as the landlord who reversed history and returned the islands to common ownership?

There is a flat-faced appeal to vanity in that but, in response, I can only say that I couldn’t think of giving the islands away, that it would not be fair to my own son and that the expression of the dilemma is in the solution I propose: community-minded private ownership, with a resolution to share this place as much and as widely as we can.

The question remains, of course: what happens when you pass them on? Does Tom believe in this? Will his son? And his? New Scottish legislation produced in 2001 will mean that whenever property of this kind is sold, the local community, funded by Lottery money, will have the right to buy it at a market price. That is fine by me: if for whatever reason we have to sell the Shiants – and I hope it never comes – then community ownership is as good an idea as any. But that legislation will not apply to a transfer of land within the same family. Nor do I want to hedge Tom’s freedom about with covenants and restrictions on what he can do with the islands. If he doesn’t have any sense of the social obligation which ownership of land entails, or of the vitality of the tradition to which ownership of these islands gives us access, then no restrictive covenant is going to teach him. But I know him. He grasps as clearly as anyone the need to be generous. The question is not, in the end, one of regulation but of a culture of mutual respect and decent regard, not only because the history in these islands is of eviction and dispossession, but because respect and decency are absolutely good in themselves.

As the winter comes again, the gales return. The wind blows pieces out of the big cairns on the top of Eilean an Tighe, and the stones lie as lumpy grey hail around them on the grass. When you get up in the morning, it is to a wind-combed world. The surface of the sea is woolly with the spray and there’s a haze above it like the fine hairs on a cashmere jersey. In the house, the roof space roars as the wind sucks and tugs at it and outside, there’s a fierce clarity, a denuded air, to the islands, as if they were on the butcher’s slab and the wind was slicing the flesh away.

There are days when the strength of wind can scarcely be imagined. I was talking to Bullet Cunningham about Freyja. What did he think of the boat? Did it look well made? ‘Oh yes, it looks like it’s all right. You’ll have to tie her down though. You’ll have to put some weight in her. And tie her well. Or in a bad gale of wind the wind will lift her up.’

‘But it weighs six hundred pounds,’ I said.

‘Oh yes, the wind will lift it, no bother. We had three boats on the Shiants once, on the beach there, tied together and we went over from the cottage where we were staying and the gale was bad and they were like that.’ He put his hand vertically in the air like a blade. ‘They were standing on their bows like that, the three of them upright. We had to pull them down and put more stones in them.’

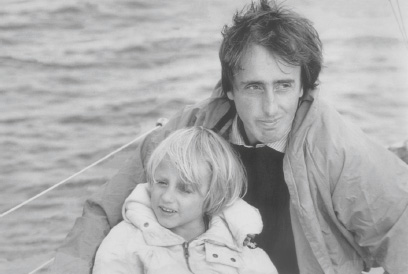

The wind is inescapable here. Its relentlessness more than its strength is what can make you unhappy. I have been here with my wife Sarah at times when the rain and wind have slapped against us day after day. We were staying in a tent – the house felt too ratty – and we went to bed in the wind and woke up in the wind. Every voice was blurred by the wind, every minute besieged by it. It did not go well. She wanted to leave. She was unable to see the point in being out on a shelterless rock in a meaningless sea, under a muffled grey sky, where there are no loos and no baths, where there is not even a little copse or spinney in which one can sit down to read, where the house itself is little better than a shed, where the wind blows and blows and where your husband is for some reason obsessed with every fact and detail of this godforsaken nowhere.

So I took her, on one of these unhappy, disconnected days, to a place on the spit of rock through which the natural arch is driven, at the north-east corner of Garbh Eilean. It is quite a scramble to get there, down a crumbly half-cliff face, across some weed-slithered rocks at sea-level, and then up again over barnacle-encrusted boulders. But once there – and this only works in a long, old swell – you can find yourself suddenly in the presence of something marvellous. All is quiet; you are for a moment in the lee of the island and the air is able to mimic stillness. Then, from nowhere, it happens. I suppose it is some effect of air and water, the compression of one by the other, but it is not science you encounter. Quite casually, and with no fanfare, no advance warning, from between your feet the islands start to groan. A long, deep moaning emerges from the slits between the dolerite slabs. It begins slowly and builds, a deep and exhausted exhalation. It is like finding a room in which you thought you were alone suddenly occupied by another, a voice emerging from a long dead body.

Did that make things better? Not really. It was scarcely a Martini advertisement, nor perhaps the most appropriate way of convincing a disenchanted spouse that the Shiants were wonderful. Where were the sandy beaches? Where the machair, the sweet, shell-sand pastures, the fertility, the richness, the sense of life beyond the bone?

I was not finished. On the next quiet day, we went cave-visiting. One, just beyond the natural arch, is a huge fretted cavern, forty yards long, the water inside it invisibly deep and turquoise blue, gurgling and slopping against the pink, coralline-encrusted walls. You can reach it only by boat, and if you tethered a raft in there, you could hold a dance inside, candelabra suspended from the dripping roof, shags and black guillemots alert to the music.

But even that is not the greatest of the Shiants’ sea displays. Out at the far north-western tip of Garbh Eilean, where the Stewarts attempted to kill their shepherd and where Mrs MacAulay fell to her death, where you can go only in a calm, is the most haunting sea cave of all. Its mouth is covered except at low tide. Even then, not much of it appears. A little jagged-arched orifice opens above the guano-thick green of the sea. The birds hawk and hiss, gab and gibber above you. The echo of their voices runs three times around the little amphitheatre in which the cave is set, rising to its own small crescendos and then dropping into silence. Down on the sea, the noise ricochets around you, the fishwives of Hell on a weekend outing. It is dark and cold in here. The sun never reaches this place.

We look at the mouth of the cave. Inside, as the swell slops back from the entrance, you see the pink and dangling innards, rock tonsils thickened with coralline reaching down to the tongue of the sea. It is the gullet of the monster. The opening is too small for a boat to enter – I have slipped the nose of a canoe in there, no more – and you must wait outside. And wait you must because this cave will in time, not with every swell, work its magic. It comes soon enough. The swell withdraws, and after it a barrel-deep, reverberant, bass-booming of the rock, followed, and this is the moment at which you abandon all critical distance, by a breath of foggy air, rolling and curling out of the mouth, expelled ten or twenty yards towards you, enveloping you, your boat and your wife in its salty, geological folds. Who needs a flowery meadow when islands can do that for you? Who thinks of legislation or designation or clan history or the politics of landscape when the wild can so easily step outside any frame designed to encompass or reduce it?

October is buffeting onwards. I am alone, writing in the house, with the light of the two paraffin lamps on the table beside me, the dogs curled into doughnuts by the fire and the waves breaking on the shore outside, less than a stone’s throw away. The places in which I swam between the anemones and the bladderwrack in the summer are chaos now. From time to time, a handful of the sea spray lands on the windows and rattles them. Sarah is at home with the girls and the wind shuffles through its endless conversations outside. A gannet is sailing above the storm, in close beside the beach so that I can watch it above the stirred and stained green-and-white surface of the sea. The day is dark and the gannet is lit like a crucifixion against it. I could never tire of this, never think of anything I would rather watch, nor of any place I would rather be than here, in front of the endless renewing of the sea bird’s genius, again and again carving its path inside the wind, holding and playing with all the mobility that surrounds it like a magician with his silks, before the moment comes, it pauses and plunges for the kill, the sudden folded, twisted purpose, the immersion, disappearance and the detonation of the surf. The wind bellows in my ears as if in a shell. No one can own this, no individual, no community. This is beyond all owning, a persistence and an energy which exists despite the squabbling over names and titles, not because of it.

I had wanted to have my son Tom with me at this end of the year. I am here to see the geese returning from Greenland and I wanted him here with me, but he is at school and I couldn’t take him away. Perhaps these moments are better alone, anyway. What would he have done as I sat for hours at this table writing about the islands which, I am sure, come for him with all the burden of my own expectations attached? I sometimes wonder if they are not too much of a parental landscape for him. Will my own presence not loom too much over them?

It didn’t happen with me and my father. He made the gift a real one, allowing me freedom from the moment the deed was signed. A connection remained. I told him once that buying the Shiants was the best thing he had ever done and I could see that the words moved him, more I think because I had said them than because he believed it. The Shiants have been a conduit between us for years, a way of talking about something we both loved without ever having to say that we did. He wrote to me once at school about ‘a cloud of midges hanging around your head on a still evening you-know-where’ – and I can still remember the feeling that enveloped me then of an almost overwhelming sense of connectedness and significance, of this deep intimacy which a common affection for you-know-where could provide. Nothing else was quite so free or rich. That is the feeling which has fuelled the writing of this book and which I want to give Tom: not the islands but our shared attachment to them.

It may not happen, but that doesn’t matter. I don’t need Tom Nicolson to live with the intensity of Shiant-love that his father has known. All populations go through their cycles of dearth and wealth and there is no reason why my own closeness to the Shiants shouldn’t diminish for a lifetime or two. It is for him to do what he will. Even in prospect, I love the idea of Tom being on the islands with his friends, discovering it all, feeling his way into its heart, making all the mistakes that I and my father made, slowly acquiring the odd, deep, distant attachment to a place of such unresponsive rock. But if that doesn’t happen to him, I don’t mind. His best and repeated joke to me is that When The Time Comes he is going to put a generator in and have a Sky satellite dish attached to the roof of the cottage. I will leave it ten years but in a funny way, I can’t wait to be his guest here.

The time I have had on the Shiants is coming to an end. I know the islands now more than I have ever known them, more in a way than anyone has ever known them, and as I sit here in the house I have a feeling, for a moment, of completeness and gratitude. My love affair with these islands is reaching its full term. Yesterday, one of those early winter days opened, when the whole of the Hebrides lies cold and still around you, the hills in Skye washed purple, the mountains in the Uists a faded, sea-washed blue. A big, slow swell was travelling the length of the Minch, as though the muscles were moving under the skin of the sea. I went up to the far north cliff of Garbh Eilean and lay down there on the cold turf where the tips of the grasses are reddening with the acid in the soil. I put my head over the edge of the cliff and watched the sea pulling at the black seal reef five hundred feet below me. I had my mobile in my pocket. The reception is good up there and I rang Tom at his sixth form college in Chichester. ‘Listen, Tom, listen,’ I said and held the phone so that he could hear the sea.

‘You’re mad,’ he said.

‘I know.’

‘Have you seen the geese yet?’

‘No, nothing yet. But it’s lovely here.’

‘I know it is, Dad. I’ve gotta go. I’ve got History. Talk to you soon. Bye.’

I was left alone in the silence, with the pale sun on my face, and, as the dogs nosed for nothing in the grasses, I started to fall asleep there to the long, asthmatic rhythm of the surf. The islands embraced and enveloped me. Twenty yards to my left the Viking was asleep in his grave and the words of Auden’s poem ran on in my mind:

Look, stranger, at this island now …

Stand stable here

And silent be,

That through the channels of the ear

May wander like a river

The swaying sound of the sea.