Diving Ducks

Surf Scoters foraging for clams in the ocean

Scoters are diving ducks, submerging completely to find food in deep water. They swallow whole clams, which are crushed in their powerful gizzard.

Surf Scoters foraging for clams in the ocean

Scoters are diving ducks, submerging completely to find food in deep water. They swallow whole clams, which are crushed in their powerful gizzard.

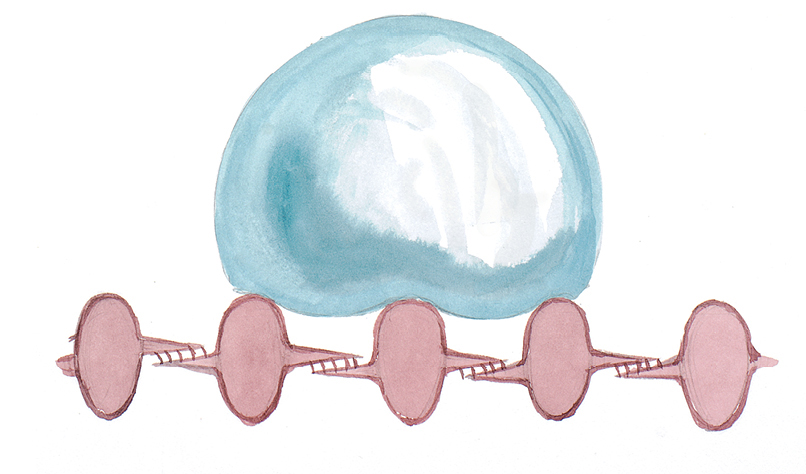

■ We rely on our kidneys to remove excess salt and other contaminants from our bodies. In addition to kidneys, birds have salt glands, located above the eyes on top of the skull, which concentrate salt from the blood and excrete it. This highly concentrated salt solution drips out of their nostrils. The glands use countercurrent circulation to transfer salt from blood to water (see this page), like our kidneys, but they are much more efficient. In one experiment, a gull was given saltwater amounting to nearly 10 percent of its body weight, and all of the excess salt had been cleared from the body within three hours, with no ill effects. (Don’t try this at home!) Salt removal is especially challenging for birds like scoters that feed on clams and other invertebrates in the ocean, since those animals have body fluids as salty as the water they live in (unlike fish, which maintain a salt concentration in their bodies lower than that of seawater). The salt gland shrinks when scoters spend the summer on freshwater lakes, and grows larger when they move to the ocean in the winter.

The head of a Surf Scoter, with the salt gland in blue

■ Feathers are waterproof mainly because of their structure. The surface tension of water causes water droplets to maintain their shape, and the overlapping and linked barbs of feathers leave openings too small for liquid water to flow through (the same concept as GORE-TEX fabric). The hooked barbules are needed not just to keep the barbs from being pulled apart but also from being pushed too close together, keeping them all at the correct spacing. That spacing has evolved differently depending on a species’s habits. Birds that dive underwater have barbs very close together to keep water from being forced through under pressure. But while it prevents water penetration, the closest barb spacing allows water to make contact across the barbs and soak the surface of the feather. Land birds have barbs farther apart, which maximizes water repellency and prevents water from soaking the surface. But this allows water to penetrate through the spaces under pressure (for example, if a songbird ever tried to dive underwater). Ducks such as scoters have compromised with medium barb spacing. They enhance their water repellency with preen oil, and limit water penetration by having many overlapping feathers that provide several layers of protection.

Like water off a duck’s back—a drop of water resting on the barbs of a feather

■ In water birds like the Surf Scoter, each feather is very stiff and strongly curved so that its tip is pressed tightly against the feather behind it. Feathers grow close together and overlap to provide multiple layers of water resistance, all forming a firm but flexible shell that keeps water out and traps a layer of dry insulating down underneath. Land birds such as crows have fewer, straighter, more flexible feathers, forming a shell that is very water repellent but not good enough for swimming.

A cross-section of the body, showing the feathers of a scoter (left) and a crow (right)