Small Sandpipers

Sanderlings running on the beach

This species spends all day running: down the beach to find food uncovered by a receding wave, and back up the beach to escape the next wave.

Sanderlings running on the beach

This species spends all day running: down the beach to find food uncovered by a receding wave, and back up the beach to escape the next wave.

■ The swerving movements of a flock of sandpipers in flight are among the most remarkable spectacles in nature, and recent research has provided some insight. There is no leader—any bird in the flock can suggest a turn. The other birds see the change in direction, and if they also turn the reaction is transmitted through the flock at a constant rate (much like a “wave” in a sports stadium). A flock the size of a football field can change direction in this way in less than three seconds. Each individual bird just switches to the new direction, changing their position relative to their neighbors like in a marching band. Turns are usually initiated by birds at the edges of the flock, and they usually swerve into the flock. Being at the edge gives them a better view of any potential danger, and also makes them more vulnerable to attack. Some turns are in response to actual danger, but many are likely just prompted by a desire to get away from the edge. As an edge bird gets nervous and swerves into the flock, the rest of the flock reacts. The result is a dizzying, swirling, unpredictable mass of birds that is very difficult for a predator to attack. Even if most of the turns are false alarms, frequent and sudden turns make the group safer.

A flock of sandpipers before and after a turn. The edge bird (light color) initiates the turn, all birds turn on the same radius in response, and the edge bird ends up in the middle of the flock after the turn.

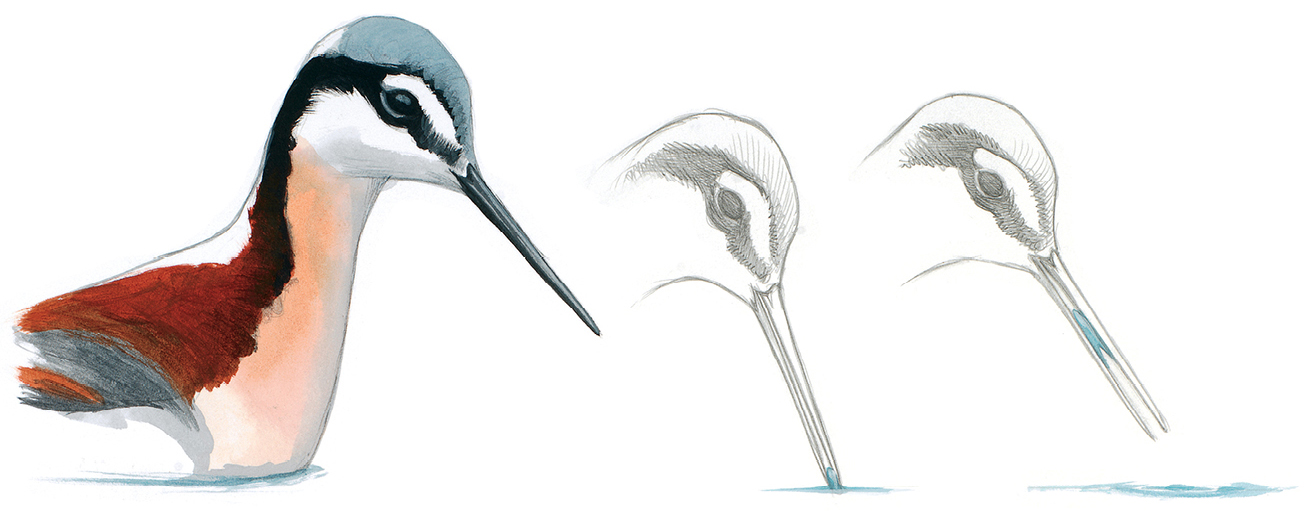

■ The tip of a sandpiper’s bill is very sensitive to touch, and this even allows them to sense things indirectly. When the bill is forced into wet sand or mud, water is displaced and moves away. If the flow of water is blocked by something in the sand or mud (like a small clam), slightly higher pressure builds up where the water is squeezed between the bird’s bill and the clam. Sensing that pressure, the bird knows that probing in that direction might be worthwhile.

A Dunlin probing in mud

■ Observing a flock of sandpipers foraging on a mud flat, you might notice that they are constantly picking at the surface, or probing into the mud or water, but rarely lift their heads. Each one is picking up food with the tip of its bill, and getting the food into their mouth, but the bill is constantly pointed down, seeming to defy gravity. The explanation involves a simple bit of physics—taking advantage of the surface tension of water. When the bird grasps a tiny food item in the tip of its bill, a droplet of water comes along with the food. Because the droplet of water tends to hold together, the bird can move the water up the length of its bill by slightly separating the mandibles repeatedly, and the moving water carries the food with it. Once in the mouth, the water is squeezed away and shaken off, the food is swallowed, and the bird can go back for more food. High-speed video taken of Red-necked Phalaropes shows that they can transport their prey from bill tip to mouth in as little as 0.01 seconds, simply by using surface tension to pull in a drop of water. That’s about thirty times faster than the blink of an eye.

A Wilson’s Phalarope manipulating food into its mouth