Eagles

Bald Eagle eating a salmon

The Bald Eagle was endangered in the 1970s, decimated by DDT poisoning and other threats. With protection the species is now widespread again.

Bald Eagle eating a salmon

The Bald Eagle was endangered in the 1970s, decimated by DDT poisoning and other threats. With protection the species is now widespread again.

■ We call someone “eagle-eyed” if they spot very distant objects. This expression was first used in the 1500s, long before the science of eagle vision was known, but anyone who watches eagles notices how they react to distant events that we can only see with the aid of binoculars, such as a rabbit loping across a hillside a mile away. Eagles have five times as many light-sensing cells packed into their eyes—five times as many dots per inch—so they can see a lot more detail than we can. And almost all of those cells (80 percent) are cones that see color. We have only 5 percent color-sensing cones and 95 percent rods for dark-light vision. In addition, each of the eagle’s cone cells has a colored oil droplet that acts as a filter to block some wavelengths (colors) of light, further enhancing their color vision. We can look through 5x binoculars to approximate an eagle’s visual acuity, but we have no way to simulate their color vision.

Because of the position of the fovea, this Bald Eagle is looking directly at you (with one eye).

■ Look at a single word in this sentence, and then try to read the words around it without moving your eyes. That tiny area of detail in the center of your vision is because of the fovea, a small pit in the retina of each eye where light-sensing cells are more tightly packed. We have one fovea in each eye, both eyes focus on the same point, and we see one spot of detail. Most of our visual field, over 110 degrees, is viewed by both eyes (this is called “binocular vision”). Eagles, however, have two foveae in each eye, for a total of four, and they all point in different directions. Their two eyes only overlap in a narrow arc of less than 20 degrees, and they don’t see much detail there. An eagle is seeing four different areas of detail at all times, as well as nearly 360 degrees of peripheral vision! One fovea in each eye is aimed almost straight ahead, and the “strongest” fovea points out at about 45 degrees. In order to look at the sky or the ground, a bird will cock its head to one side, using one fovea of one eye to study something.

A Bald Eagle showing the lines of sight of the four foveae

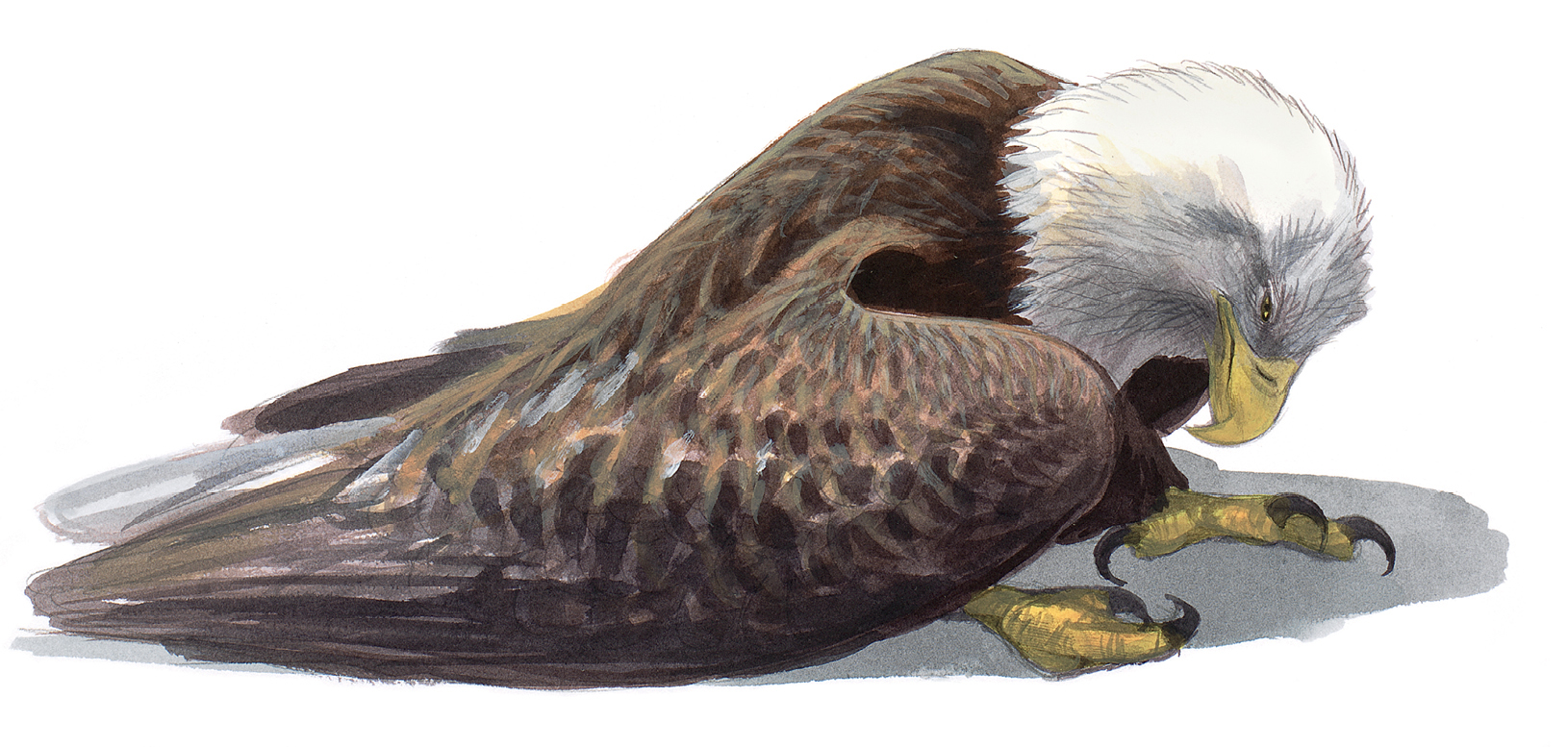

■ One of the most serious threats now facing eagles and many other birds is lead poisoning. Eagles swallow lead shot and bullets embedded in prey, or eat waterfowl that have high levels of lead (from swallowing lead shot and fishing weights). Because a bird’s digestive system relies on a muscular gizzard (stomach) and strong acids to pulverize and dissolve food, harder materials like rocks, seeds, bones, or metal fragments are simply ground up until they are small enough to pass through. This means that bits of lead can remain in the gizzard, breaking down and releasing lead into the body, for many days. Signs of severe lead poisoning include weakness, lethargy, and green feces. All of the lead involved in these poisonings comes from humans, and simply using lead alternatives in ammunition and fishing weights would solve this problem.

This Bald Eagle is suffering from severe lead poisoning and needs treatment to have any chance of survival.