More Swallows

Tree Swallows roosting on reeds

Swallows often congregate around wetlands, where insects are abundant.

Tree Swallows roosting on reeds

Swallows often congregate around wetlands, where insects are abundant.

■ Will the same individual birds return to the same territory every year? Almost certainly . . . if they survive the winter (see this page). Most species are very faithful to their nesting site, especially if they were successful at raising young, and will return every year to the same territory. Furthermore, one-year-old birds returning to breed for the first time typically come back to the area where they were raised. One study in Pennsylvania found that Tree Swallows returned to within a few miles of the nesting box where they were raised, and made their own nesting attempts in that area. This connection to familiar places is not just for nesting sites. Many migratory species follow the same migration route and use the same winter territory each year.

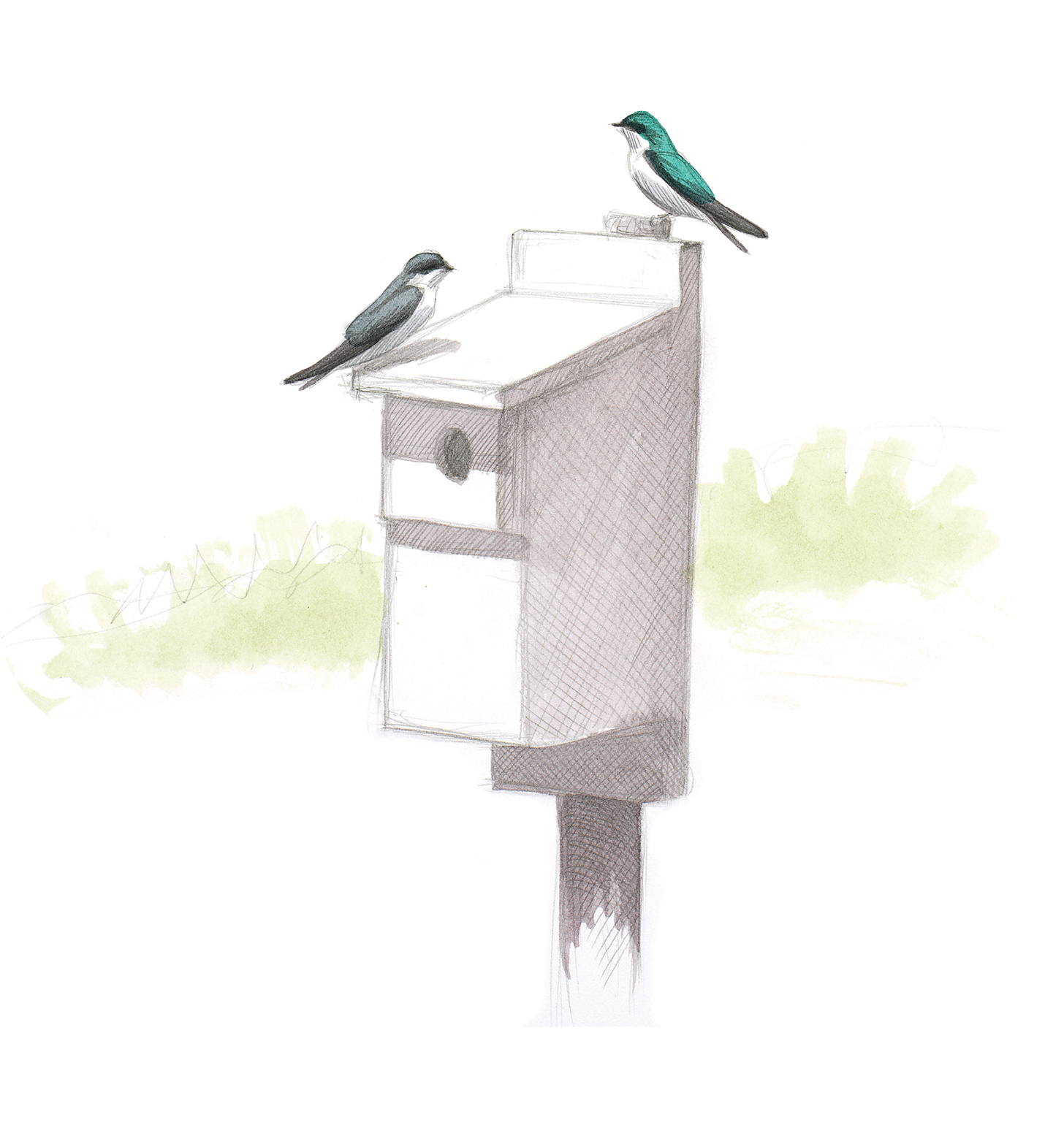

A pair of Tree Swallows on a nesting box

■ All baby songbirds (such as this Tree Swallow) hatch naked, with eyes closed, and require constant feeding, warming, and protection by the parents to survive. These are known as altricial young. One advantage of having altricial young rather than precocial young (see this page) is that the nesting female can lay smaller eggs that require fewer resources, since the eggs hatch at an earlier stage of development. But that simply delays the work until later, and adult swallows have to invest a lot of time and energy to care for the young after they hatch. Another advantage of the altricial system is that it allows more brain growth after hatching. Precocial young like ducks and geese hatch with nearly fully developed brains and feed themselves. Altricial young are helpless at hatching, but the parents deliver a steady supply of high-protein food (see this page), so the brains of the young birds grow substantially after hatching and adults have proportionally larger brains than in precocial species.

A just-hatched Tree Swallow

■ The details of an individual wing feather are amazing! Researchers exploring the precise shape and structure of feathers continue to discover new details, some of which can be applied to human engineering challenges. The shaft is a foam-filled tube—a structure that provides high strength and stiffness with very low weight. The tube is formed by layers of fibers oriented in different directions, just like modern high-tech carbon fiber tubes. The changing shape of the feather shaft, from round at the base to rectangular and then square, gives it different properties of stiffness and flexibility at each point. The shape of individual barbs is oval, with more material at the top and bottom. This makes each barb very resistant to flexing up or down but more flexible from side to side. When locked together with other barbs, they form a strong flat surface for flight. But if a feather hits something, the individual barbs simply twist, disengage from their neighbors, and bend to absorb the impact.

Cross-sections of different points on a typical wing feather

Cross-sections of a feather barb