Titmice

Oak Titmice

Related to chickadees, the four species of titmice are all grayish with short crests.

Oak Titmice

Related to chickadees, the four species of titmice are all grayish with short crests.

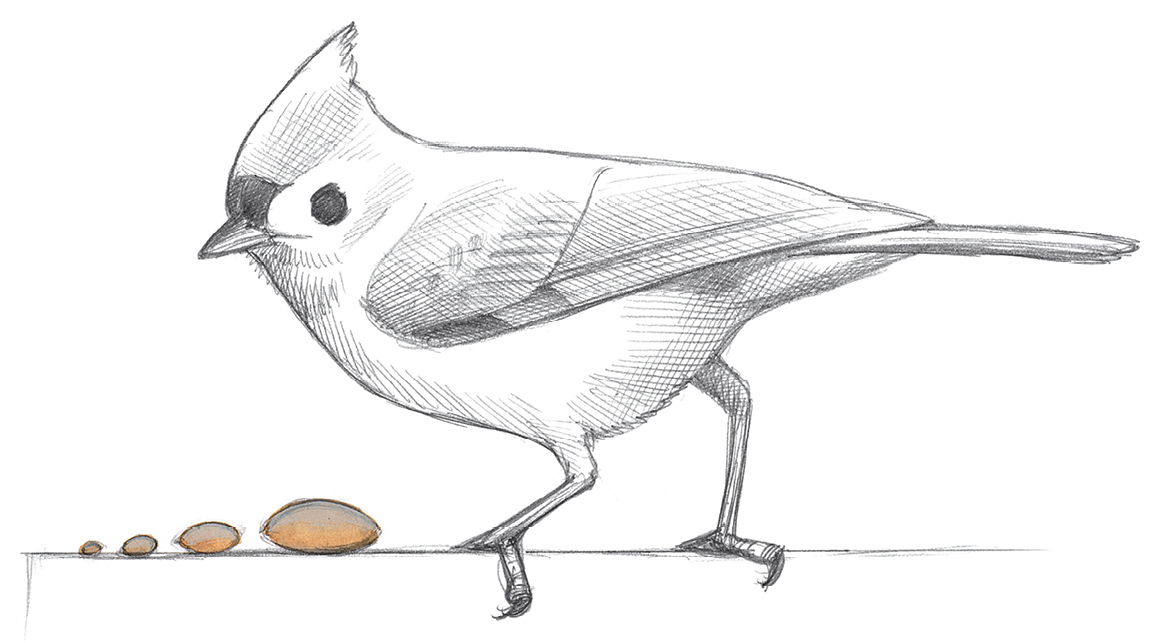

■ The theory of optimal foraging predicts that birds will modify their foraging behavior in a way that maximizes benefits while minimizing effort and risk. Confronted with seeds of four different sizes, you might expect this titmouse to grab the biggest one and head for the woods. But a larger seed is harder to carry, more conspicuous to anyone watching, and will take longer to break up and consume. All of this involves more effort and increases the risk of attack by thieves and predators. Small seeds usually offer less food value and might not be worth the effort, but if a small seed has high fat content and a lot of calories it could be the best choice. The optimal seed has just the right balance of benefits and costs. This multi-faceted decision-making is going on every time a titmouse visits a bird feeder, and there are plenty of times when the cost-benefit analysis leads a bird to choose the larger seed, but it is always a considered choice.

A Tufted Titmouse faced with a decision

■ Titmice (and chickadees), unlike many other small birds, do not eat right at the bird feeder. They carry food away from where they find it, to be consumed on another perch. You will usually see them fly to a bird feeder, sort through the seeds there for a second or two, then select one and fly back into the woods to eat it or hide it. This makes their choice of seed a bit more important than if they were just sitting at the feeder and eating. While sorting they are apparently judging the weight, as a way of guessing the fat content (fat is denser, so given two similarly sized seeds, the heavier one is likely to have more fat). Once in the cover of woods, the titmouse holds the food item between its feet, and uses its bill to hammer and pry it apart for eating.

A Tufted Titmouse flying away from the feeder after selecting a seed

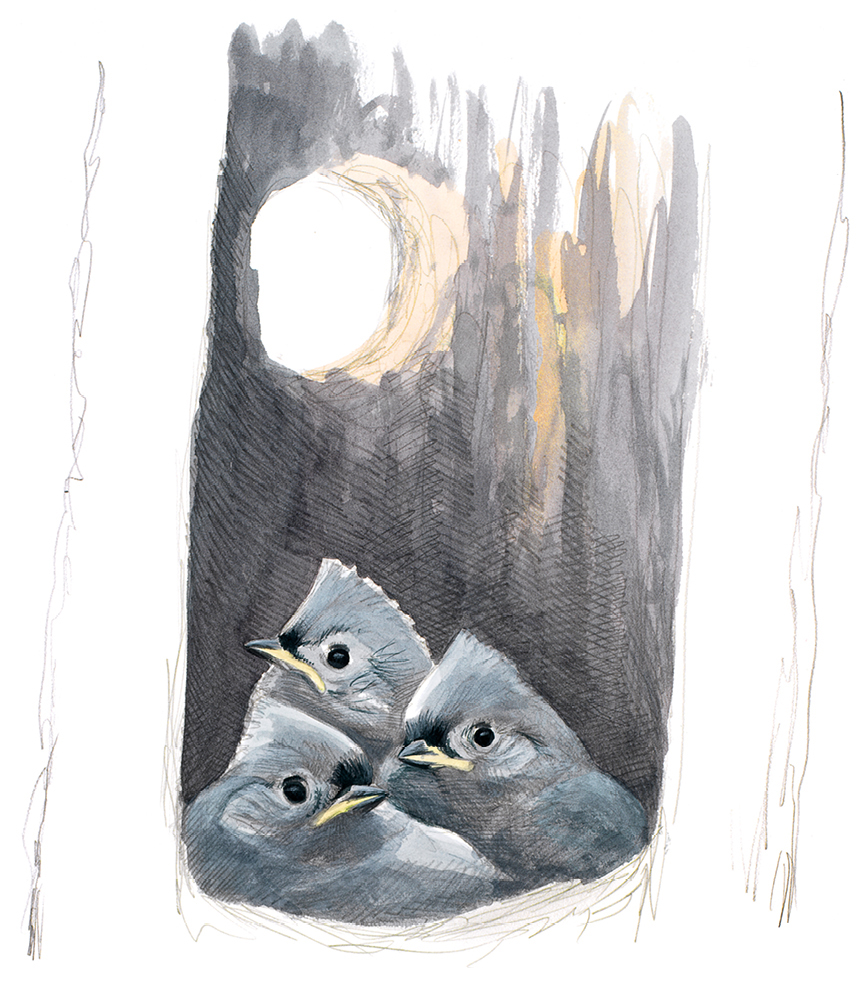

■ Songbirds typically lay four or five eggs, and begin incubating after the last egg has been laid so that all develop together and hatch close to the same time. In the Tufted Titmouse this incubation period averages thirteen days, and in the Eastern Phoebe sixteen days. Among other species the average time to hatching differs a lot. Why have these differences evolved? A recent review suggests that one of the most important factors is sibling rivalry. A young bird gains a selfish advantage by hatching sooner than its nest-mates, and this “race” to hatching leads to shorter incubation times. This is balanced, of course, by the need for the embryo to develop fully so it will grow into a successful adult. In species that lay a single egg, or with asynchronous hatching (see this page), the sibling hierarchy is predetermined and incubation times are relatively long.

Tufted Titmouse nestlings nearly ready to fledge