Bluebirds

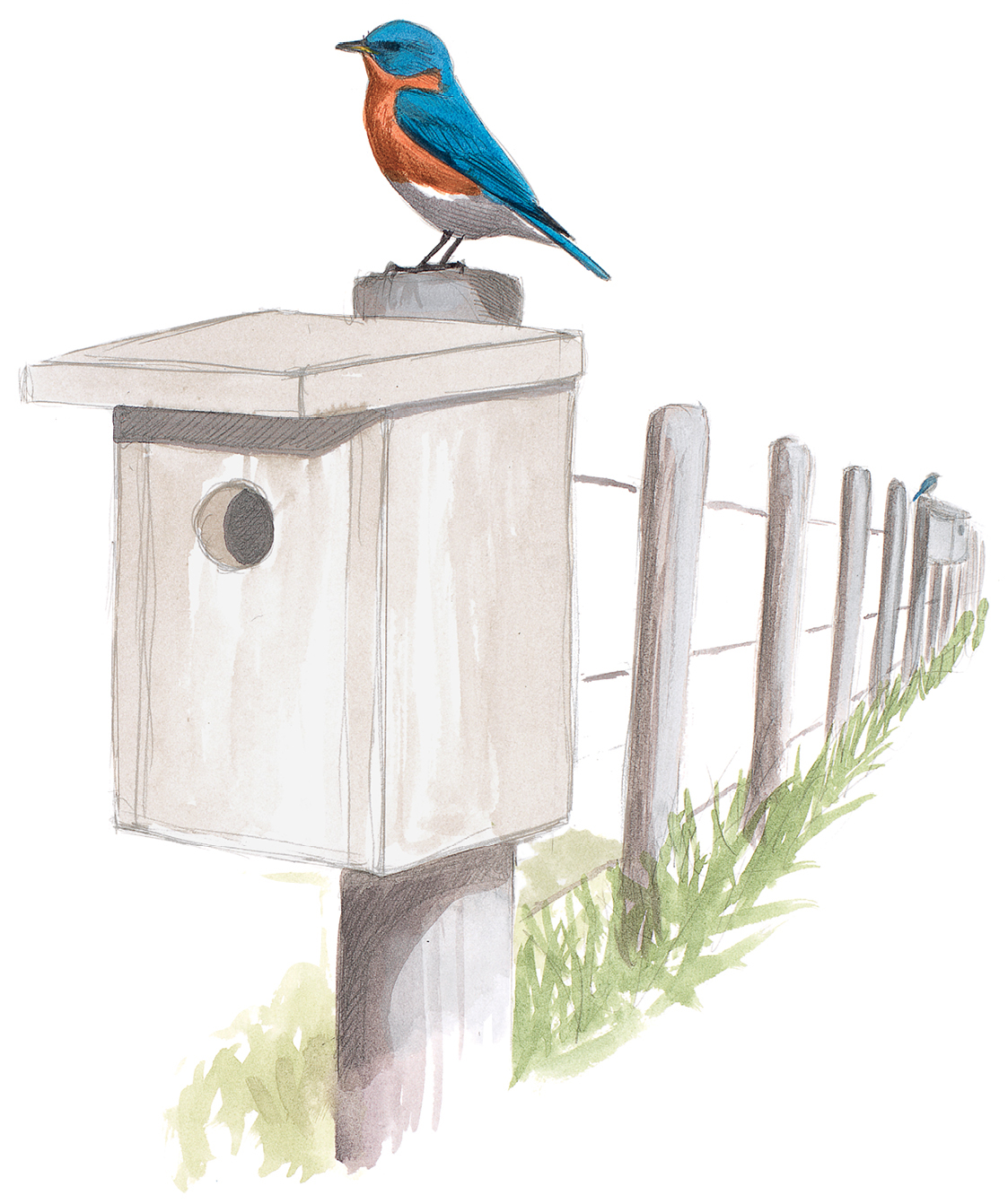

A male Eastern Bluebird investigating a potential nest site

Bluebird populations have increased greatly in the last fifty years, probably helped by nest boxes.

A male Eastern Bluebird investigating a potential nest site

Bluebird populations have increased greatly in the last fifty years, probably helped by nest boxes.

■ There is no blue pigment in birds—all blue color is produced by the microscopic structure of the feathers. If you find a blue feather, you will notice that it is only blue on one side, and it looks drab brownish when light shines through it. The bluebird’s color relies on the same physical principles as iridescent hummingbird feathers, in which a coherent scattering of light reinforces some wavelengths and diminishes others (see this page), but the structure behind it is quite different. Instead of multiple flat layers of material to reflect light, bluebirds have a spongy layer filled with tiny air pockets and channels. These air pockets are all about the same size, and together they produce a patterned structure with the correct intervals to match the wavelength of blue light. Waves of blue light scattered from one air pocket will be in phase with waves of blue light from some of the other air pockets. Light of other wavelengths will be out of phase and mostly invisible. Because the air pockets are evenly distributed throughout this spongy layer, the effects on light traveling in any direction are the same. Unlike the iridescent throat colors of hummingbirds, the blue color of a bluebird looks similar from all angles.

The solid surface of one barb (brown) with the spongy layer of tiny air channels (gray). The larger black dots are granules of melanin that capture any light that makes it through the spongy layer.

■ Bluebirds, like many other species, build their nest inside a cavity. This is usually an old woodpecker hole, but it’s sometimes a rotted hollow branch, a crevice in a building, or a similar location. They rely on an abundance of standing dead trees and woodpeckers to provide nest sites, and if dead trees are removed, as they are in many urban and suburban settings, there are few places for bluebirds to nest. Fortunately, bluebirds are happy to accept birdhouses, and thousands of people across North America help to maintain “bluebird trails” that provide nest boxes along miles of country roads.

A male Eastern Bluebird on a nest box

■ If you find a broken eggshell on the ground, the shape of the pieces can give some information about what happened. If an egg hatches normally, the chick chips away a ring around the widest part of the egg and the egg separates into two halves. The parents then carry the eggshells from the nest and scatter them some distance away. An eggshell cut straight across in this way is likely to be the result of successful hatching nearby. Eggshells in smaller pieces, fragmented or crushed, could be the result of an accident or predation. Given the opportunity, many species of birds and small mammals will eat the contents of an egg and leave the shell behind.

A broken egg on the ground (right) indicates predation or an accident; an egg neatly split in half (left) indicates hatching.